Sir Henry Wilson, 1st Baronet

| Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, Bt | |

|---|---|

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet | |

| Born |

5 May 1864 County Longford, Ireland |

| Died |

22 June 1922 (aged 58) London, England |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1882–1922 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands held |

Chief of the Imperial General Staff Eastern Command IV Corps Staff College, Camberley 9th Provisional Battalion, Rifle Brigade |

| Battles/wars |

Third Anglo-Burmese War Second Boer War First World War |

| Awards |

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order Mentioned in Despatches Légion d'honneur (France) Order of Leopold (Belgium) Croix de guerre (Belgium) Order of Chia-Ha (China) Distinguished Service Medal (United States) Order of the White Elephant (Siam) Order of the Rising Sun (Japan) Order of the Redeemer (Greece) |

| Other work | Member of Parliament for North Down (1922) |

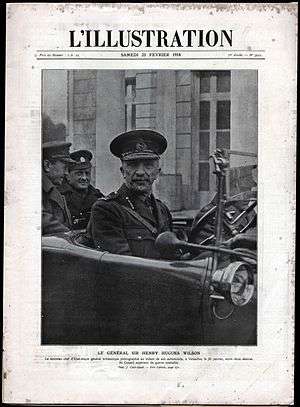

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet GCB, DSO (5 May 1864 – 22 June 1922) was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Irish unionist politician.

Wilson served as Commandant of the Staff College, Camberley, and then as Director of Military Operations at the War Office, in which post he played a vital role in drawing up plans to deploy an Expeditionary Force to France in the event of war. During these years Wilson acquired a reputation as a political intriguer for his role in agitating for the introduction of conscription and in the Curragh Incident of 1914, when he encouraged senior officers to resign rather than move against the Ulster Volunteers (UVF).

As Sub Chief of Staff to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Wilson was Sir John French's most important advisor during the 1914 campaign, but his poor relations with Haig and Robertson saw him sidelined from top decision-making in the middle years of the war. He played an important role in Anglo-French military relations in 1915 and – after his only experience of field command as a corps commander in 1916[1] – again as an ally of the controversial General Nivelle in early 1917. Later in 1917 he was informal military advisor to the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and then British Permanent Military Representative at the Supreme War Council at Versailles.

In 1918 Wilson served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (the professional head of the British Army). He continued to hold this position after the war, a time when the Army was being sharply reduced in size whilst attempting to contain industrial unrest in the UK and nationalist unrest in Mesopotamia, Iraq and Egypt. He also played an important role in the Irish War of Independence.

After retiring from the army, Wilson served briefly as a Member of Parliament, and also as security advisor to the Northern Ireland government. He was assassinated on his own doorstep by two IRA gunmen in 1922 whilst returning home from unveiling a war memorial at Liverpool Street station.

Family background

The Wilson family claimed to have arrived in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, with William of Orange in 1690, but may well have lived in the area prior to that. They prospered in the Belfast shipping business in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century and following the Encumbered Estates Act of 1849 became landowners in counties Dublin, Westmeath and Longford. Wilson’s father James, the youngest of four sons, inherited Currygrane in Ballinalee, County Longford (1,200 acres, worth £835 in 1878), making him a middling landowner, more than a large farmer but not a “Big House” Ascendancy landlord; by 1901 the Currygrane estate had 49 Catholic and 13 Protestant (10 of them the Wilson family) inhabitants. James Wilson served as a High sheriff, a Justice of the peace and Deputy Lieutenant for Longford, there being no elected local government in Ireland until 1898, and he and his oldest son Jemmy attended Trinity College, Dublin. There is no record of Land League activity on the estate, and as late as the 1960s the IRA leader Sean MacEoin remembered the Wilsons as having been fair landlords and employers.[2] The Wilsons also owned Frascati, an eighteenth century house at Blackrock, near Dublin.[3]

Born at Currygrane, Henry Wilson was the second of James and Constance Wilson's four sons (he also had three sisters). He attended Marlborough public school between September 1877 and Easter 1880, before leaving for a crammer to prepare for the Army. One of Wilson’s younger brothers also became an army officer and the other a land agent.[4]

Wilson spoke with an Irish accent and at times regarded himself as British, Irish or an Ulsterman. Like many Anglo-Irish or Scots of his era, he often referred to Britain as "England." He may well, like many Anglo-Irish, have played up his “Irishness” in England and regarded himself as more “Anglo-” whilst in Ireland, and may well also have agreed with his brother Jemmy that Ireland was not “homogenous” enough to be "a Nation." Wilson was also a devout member of the Church of Ireland, which evolved a distinctive Irish and Low Church identity after Disestablishment in 1869. Wilson was not an Orangeman, and did on occasion attend Roman Catholic services, but disliked “Romish” ritual, especially when practised by Anglican clergymen. He enjoyed good personal relations with Catholics, although there are unsubstantiated claims that he disliked George MacDonogh, and tried to block the promotion of William Hickie, as both men were Catholics.[5]

Early career

Junior officer

Between 1880 and 1882 Wilson made several unsuccessful attempts to get into the British Army officer-training establishments, two to enter the Royal Military Academy (Woolwich) and three for the Royal Military College (although there were nine applicants for every place in the late 1870s). The entrance examinations to both relied heavily on rote learning. Sir John Fortescue later (in 1927) claimed that this was because as a tall boy he needed “time for his brain to develop”.[6][7][8]

Like French and Spears, Wilson acquired his commission “by the back door” as it was then known, by first becoming a militia officer. In December 1882 he joined the Longford Militia, which was also the 6th (militia) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade. He also trained with the 5th Munster Fusiliers.[9][10] After two periods of training he was eligible to apply for a regular commission, and after further cramming in the winter of 1883–4, and trips to Algiers and Darmstadt to learn French and German, he sat the Army exam in July 1884. He was commissioned into the Royal Irish Regiment, but soon transferred into the more prestigious Rifle Brigade.[9][11][12]

Early in 1885 Wilson was posted with the 1st Battalion to India, where he took up polo and big game hunting. In November 1886 he was posted the Upper Irawaddy, just south of Mandalay, in recently annexed Burma to take part in the Third Burmese War, whose counter-insurgency operations in the Arakan Hills became known as “the subalterns’ war”. The British troops were organised into mounted infantry, accompanied by “Goorkha police”. Wilson worked with Henry Rawlinson of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, who described him in his diary as “a very good chap”. On 5 May 1887 he was wounded above the left eye. The wound did not heal and after six months in Calcutta he spent almost the whole of 1888 recuperating in Ireland until he was passed for regimental duty. He was left disfigured.[13] His wound earned him the nicknames “Ugly Wilson” and “the ugliest man in the British Army”.[8]

Marriage

Whilst in Ireland Wilson began courting Cecil Mary Wray, who was two years his senior. Her family, who had come over to Ireland late in Elizabeth I’s reign, had owned an estate called Ardamona near Lough Eske, Donegal, the profitability of which had never recovered from the Irish potato famine of the 1840s. On 26 December 1849 two kegs of explosive were set off outside the house, after which the family only ever spent one more winter there. From 1850 Cecil‘s father George Wray had worked as a land agent, latterly for Lord Drogheda’s estates in Kildare, until his death in 1878. Cecil grew up in straitened circumstances, and her views on Irish politics appear to have been rather more hardline than her husband’s. They were married on 3 October 1891.[14]

The Wilsons were childless.[15] Wilson lavished affection on their pets (including a dog “Paddles”) and other people’s children. They gave a home to young Lord Guilford in 1895-6 and Cecil’s niece Leonora (“Little Trench”) from December 1902.[16]

Staff College

Whilst contemplating marriage, Wilson began to study for Staff College in 1888, possibly as attendance at Staff College was not only cheaper than service with a smart regiment but also opened up the possibility of promotion. At this time Wilson had a private income of £200 a year from a £6,000 trust fund. At the end of 1888 Wilson was passed fit for home (but not overseas) service, and joined the 2nd battalion at Dover early in 1889.[17]

Wilson was elected to White's in 1889. Although White's membership books for the period do not survive, when his brother Jemmy was elected to Brooks's in 1894, his proposer and seconder were prominent members of the Anglo-Irish elite in London.[18]

After a posting to Aldershot, Wilson was posted to Belfast in May 1890. In May 1891 he passed 15th (out of 25) into Staff College, with a few more marks than Rawlinson. French and German were amongst his worst subjects, and he began study there in January 1892.[17] After his difficulty in entering the Army, passing the entrance exam proved that he did not lack brains.[8]

Colonel Henry Hildyard became Staff College Commandant in August 1893, beginning a reform of the institution, placing more emphasis on continuous assessment (including outdoor exercises) rather than examinations. Wilson also studied under Colonel George Henderson, who encouraged students to think about military history by asking what they would have done in the place of the commanders.[19] Whilst at the College he visited the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War in March 1893.[20] Rawlinson and Thomas D'Oyly Snow were often his study partners (Aylmer Haldane also claimed the same in his 1948 autobiography, but this is not corroborated by Wilson’s diary). Launcelot Kiggell was in the year below. Rawlinson and Wilson became close friends, often staying and socialising together, and Rawlinson introduced Wilson to Lord Roberts in May 1893, whilst both men were working on a scheme for the defence of India.[19] Wilson became a protégé of Roberts.[8]

Staff officer

Wilson graduated from Staff College in December 1893 and was immediately promoted captain.[21] He was due to be posted with the 3rd Battalion to India early in 1894, but after extensive and unsuccessful lobbying – including of the Duke of Connaught – Wilson obtained a medical postponement from his doctor in Dublin. He then learned that he was to join the 1st Battalion in Hong Kong for two years, but was able (August 1894) to obtain a swap with another captain – who then died on his tour of duty. There is no clear evidence as to why Wilson was so keen to avoid overseas service. Repington, then a staff captain in the Intelligence Section at the War Office, took Wilson on a tour of French military and naval installations in July, after which he had to write a report. After a very brief service with his regiment in September, with Repington’s help Wilson came to work at the War Office in November 1894, initially as an unpaid assistant (he received a cheque from his uncle to tide him over) then succeeding to Repington’s own job.[22]

The Intelligence Division had been developed by General Henry Brackenbury in the late 1880s into a sort of substitute General Staff; Brackenbury had been succeeded by Roberts protégé General Edward Chapman in April 1891.[23] Wilson worked there for three years from November 1894.[7][23][24][25] The division had six sections, (colonial defence, four foreign and topographic & library), each containing a Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General (with the rank of major), a staff captain and a military clerk. Much of the information was from public sources or from military attaches. From November 1895 Wilson found time to assist Rawlinson with his “Officer’s Note Book” based on a previous book by Lord Wolseley, and which inspired the official “Field Service Pocket Book”.[23]

Wilson worked in Section A (France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Latin America). In April 1895, despite intensive tutoring of up to three hours most days, he failed an exam in German for a posting to Berlin. However, on 5 May 1895, his 31st birthday, he took over from Repington as staff captain of section A, making him the youngest staff officer in the British Army. His duties took him to Paris (June 1895, to inquire about the expedition to Borgu on the Upper Niger) and Brussels.[26]

Boer War

Main Article: Second Boer War

Tensions mount

In January 1896 Wilson thought the Jameson Raid “very curious” and “most extraordinary”.[27] In January 1896 he seemed likely to be appointed brigade major of the 2nd brigade at Aldershot if the current incumbent Jack Cowans, a notorious womaniser with a penchant for “rough trade”, resigned, although in the event this did not happen until early September.[27] In February 1896 he submitted a 21-page paper on Italian Eritrea, and in March 1896 he briefed Wolseley on the recent Italian defeat at Adowa.[26]

Believing war with the Transvaal “very likely” from spring 1897, Wilson canvassed for a place in any expeditionary force. That spring he helped Major H.P. Northcott, head of the British Empire section in the Intelligence Division, draw up a plan “for knocking Kruger’s head off”, and arranged a lunch with Northcott and Lord Roberts (then Commander-in-Chief, Ireland) at White’s. Leo Amery later claimed that Wilson and Lieutenant Dawnay helped Roberts draw up what would become his eventual plan for invading the Boer republics from the west. He received a medal for riding in Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, but regretted that he had not won a war medal.[28] To his regret, and unlike his friend Rawlinson, Wilson missed out on a posting to the 1898 Sudan Expedition.[27]

Under Buller in Natal

When tensions mounted again in the summer of 1899, and Sir Alfred Milner was demanding that 10,000 British troops be sent, Wilson wrote (6 July) that 40,000 troops should be sent (in the event 448,000 white troops and 45,000 Africans would be mobilised to fight 87,000 Boers).[28] Wilson was appointed Brigade Major of the 3rd brigade, now renamed the 4th or “Light” brigade at Aldershot,[29] which from 9 October was under the command of Neville Lyttelton. War was declared on 11 October 1899, and he arrived at Cape Town on 18 November.[28]

Wilson’s brigade was amongst the troops sent to Natal – by late November it was encamped on the Mooi River, 509 miles from besieged Ladysmith. Wilson’s brigade took part in the Battle of Colenso (15 December), in which British troops, advancing after an inadequate artillery bombardment, were shot down by entrenched and largely hidden Boers armed with magazine rifles. Wilson later drew to the attention of Leo Amery, who was writing the ‘’Times History of the War in South Africa’’ of how Hildyard’s 2nd brigade had advanced in open order and had suffered lighter casualties than Hart’s 5th (Irish) brigade's close order attack. After Gatacre’s defeat at Stormberg (10 December) and Methuen’s defeat at Magersfontein (11 December), the battle was the third defeat of Black Week.[30]

Wilson wrote in that there was “no go or spirit about R.B. … constant chopping & changing” (3 January 1900). Buller, who was still in command in Natal despite having been replaced by Roberts as Commander-in-Chief, was awaiting the arrival of Sir Charles Warren’s 5th Division. Artillery fire at the siege of Ladysmith could still be heard from Buller’s positions, but he rejected a proposal by Wilson that the Light Brigade cross the Tugela River at Potgieter’s Drift, 15 miles upstream. Wilson was critical both of the delay since 16 December and of Buller’s failure to share information with Lyttelton and other senior officers. In the event Buller allowed Lyttleton to cross at that spot on 16 January, with the bulk of his reinforced forces crossing unopposed at Trikhardt’s Drift 5 miles upstream the following day.[31] Wilson took credit for the Light Brigade’s diversionary artillery fire during the Trikhardt’s Drift crossing.[32]

During the ensuing Battle of Spion Kop (24 January), Wilson was critical of Buller’s lack of a proper staff, of his lack of communication, and of his interference with Warren whom he had placed in charge. In an account written after the battle (possibly a report which he wrote for Roberts in January 1902) he claimed to have wanted to draw off pressure by sending two battalions – the Scottish Rifles (Cameronians) and 60th King's Royal Rifle Corps, as well as Bethune’s Buccaneers (a Mounted Infantry unit), to occupy the Sugar Loaf two miles East-North-East of Spion Kop, where Warren’s men were under fire from three sides. Lyttelton – 25 years later – claimed that Wilson had suggested to him to send reinforcements to help Warren. Wilson’s contemporary diary is ambiguous, claiming that “we” had sent the 60th to take the Sugar Loaf, whilst Bethune’s men and the Rifles went to assist Warren, and that as the Kop became crowded Lyttelton refused Wilson’s request to send the Rifles to the Sugar Loaf to assist the 60th.[33]

After the defeat, Wilson was once again scornful of Buller’s lack of progress and of his predictions that he would be in Ladysmith by 5 February. That month saw the Light Brigade take the hill at Vaal Krantz (6 February) before being withdrawn by Buller the following evening.[34] Wilson recorded that Buller was right as he did not have the 3:1 numerical superiority needed to storm entrenched positions, but by 20 February Wilson was again expressing his frustration at Buller’s slowness in exploiting further recent victories. Leo Amery later told a malicious story of Wilson had suggested gathering the brigade majors together to arrest their commanding general, although Wilson in fact seems to have thought highly of Lyttelton at this time. He was also highly critical of Fitzroy Hart (“perfect disgrace … quite mad & incapable under fire”), commanding general of the Irish Brigade, for attacking Iniskilling Hill in close order on 24 February (see Battle of the Tugela Heights), and, on the same day, leaving the Durham Light Infantry (part of the Light Brigade) exposed to attack (Wilson visited the position, and they were withdrawn on 27 February after Wilson lobbied Lyttelton and Warren), and for leaving Wilson to organise a defence against a Boer night attack on Light Brigade HQ after refusing Light Brigade requests to post pickets. The Light Brigade finally took Iniskilling Hill on 27 February and Ladysmith was relieved the following day, allowing Wilson to meet his old friend Rawlinson, who had been besieged there, again.[35]

After the relief of Ladysmith, Wilson continued to be highly critical of the poor state of logistics and of the weak leadership of Buller and Dundonald. After the Fall of Pretoria he correctly predicted that the Boers would turn to guerrilla warfare, although he did not expect the war to last until spring 1902.[36]

On Roberts' staff

In August 1900 Wilson was summoned to see “the Chief” and appointed to assist Rawlinson at the Adjutant-General’s branch, choosing to remain there rather than return to his brigade-majorship (which passed to his brother Tono, formerly adjutant of the 60th Rifles). Part of Wilson’s motivation was his desire to return home earlier. He shared a house in Pretoria with Rawlinson and Eddie Stanley (later Lord Derby), Roberts’ secretary – they were all in their mid-thirties and socialised with Roberts’ daughters, then aged 24 and 29.[37]

Wilson was appointed Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General (1 September 1900)[38] and Roberts’ assistant military secretary in September, which meant that he returned home with Roberts in December. Lyttelton had wanted him in South Africa on his staff, whilst Kelly-Kenny wanted him on the staff of Southern Command which he was hoping to obtain. Whilst on Roberts’ staff he had made contact with Captain the Earl of Kerry (Tory MP 1908–18, later Marquess of Lansdowne), Hereward Wake (later under Wilson on the Supreme War Council), Walter Cowan (later an admiral) and Archibald Murray (later BEF Chief of Staff in 1914).[37]

Repington divorce

On 9 October 1899 Lieutenant Colonel Repington, for the sake of his career, gave Wilson his written promise ("parole") to give up his mistress Mary Garstin. Wilson had been a friend of Mary Garstin’s father, who had died in 1893, and she was a cousin of his friend Lady Guilford, who asked Wilson to get involved at Christmas 1898. On 12 February 1900 Repington told him – at Chieveley, near Colenso – that he regarded himself as absolved from his parole after learning that her husband had been spreading rumours of his other infidelities. During the divorce hearings Wilson refused Repington’s request to sign an account of what had been said at the Chieveley meeting, and was unable to grant the request of Kelly-Kenny (Adjutant-General to the Forces) for an account of the meeting as he had written no details of it in his diary (Lady Guilford had destroyed the letter which he had written her containing details). He was thus unable or unwilling to confirm Repington’s claim that he had released him from his parole. Repington believed that Wilson had “ratted” on a fellow soldier. Army gossip (Edmonds to Liddell Hart, 1935 and 1937) later had it that Wilson had deliberately ratted out a potential career rival. Repington had to resign his commission and was an important military journalist before and during the Great War.[39][40]

Edwardian period

War Office

In 1901 Wilson spent nine months working under Ian Hamilton in the War Office, working to allocate honours and awards from the recent South African War. He himself received a Mentioned in Despatches[41] as "an officer of considerable ability" who displayed "energy and success", and a Distinguished Service Order,[7][42] which Aylmer Haldane later claimed Wilson had insisted on receiving out of jealousy that he had been awarded it.[43] Wilson was also recommended for brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel on attaining a substantive majority.[44] On 31 December, referring to the bruising of egos involved in the distribution of honours (Nicholson and Kelly-Kenny both felt that they had received insufficient recognition), he commented that the job had "lost some of my old friends, but I hope not many".[43]

Between March and May 1901, at the behest of the Liberal Unionist MP Sir William Rattigan, and against the backdrop of St John Brodrick’s proposed Army reforms, Wilson – writing anonymously as "a Staff Officer" – published a series of twelve articles on Army Reform in the Lahore Civil and Military Gazette. He argued that given the recent great growth in the size of the Empire Britain could no longer rely on the Royal Navy alone. Wilson argued that the three main roles of the Army were home defence, defence of India (against Russia), Egypt and Canada (against the USA, with whom Wilson nonetheless hoped Britain would remain on friendly terms), and defence of major coaling stations and ports for the Royal Navy’s use. Unlike St John Brodrick, Wilson at this stage explicitly ruled out Britain becoming involved in a European war. Without her major colonies, he argued, Britain would suffer "the fate of Spain". He wanted 250,000 men to be made available for overseas service, not the 120,000 proposed by Brodrick, and contemplated the introduction of conscription (which had been ruled out by the Liberal Opposition).[45] In private Wilson – partly motivated by the poor performance of ill-trained Yeomanry units in South Africa – and other War Office officers were less complimentary about Brodrick’s proposed reforms than he was willing to admit in print.[46]

Battalion commander

Wilson gained both the substantive promotion to major and the promised brevet in December 1901,[47] and in 1902 became Commanding Officer of the 9th Provisional Battalion, Rifle Brigade at Colchester,[7][48] intended to supply drafts for the South African War, then still in progress. The battalion was disbanded in February 1903.[49]

Military education and training

Wilson went back to the War Office as Rawlinson’s assistant at the Department of Military Education and Training under General Sir Henry Hildyard. The three men led a committee which worked on a “Manual of Combined Training” and a “Staff Manual” which formed the basis of Field Service Regulations Part II, which was to be in force when the Army went to war in August 1914.[50] With £1,600 borrowed from his father, Wilson bought a house off Marylebone Road, from whence he would often walk to the War Office in an Irish tweed suit. On one occasion he was allegedly mistaken for a newspaper seller and accepted the penny offered for his newspaper.[50] In 1903 he became an Assistant Adjutant-General.[51]

In July 1903 he reflected, during the visit of French President Émile Loubet, on the need for a Franco-British alliance against the Germans who had “an increasing population & no political morals”.[52]

At this time Wilson was becoming friendly with political figures such as Arthur Balfour (Prime Minister), Winston Churchill (who had first met Wilson, “a haggard but jocular Major (sic)”, at Iniskilling Hill in February 1900), Leo Amery and Leo Maxse.[16] Some of St John Brodrick’s proposed reforms were criticised by the Elgin Report in August 1903 (which Wilson thought “absolutely damning”). Brodrick was being attacked in Parliament by Conservative MPs, of whom Leo Amery was one, and to whom Wilson was feeding information.[53]

Esher reforms and General Staff

On Leo Amery's suggestion Wilson's colleague Gerald Ellison was appointed Secretary of the War Office (Reconstitution) Committee (see Esher Report), which consisted of Esher, Admiral John Fisher and Sir George Clarke. Wilson approved of Esher’s aims, but not the whirlwind speed by which he began making changes at the War Office. Wilson impressed Esher, and was put in charge of the new department which managed Staff College, RMA, RMC and officers’ promotion exams.[54] Wilson often travelled around Britain and Ireland to supervise the training of officers and examinations for promotion.[55]

Wilson attended the first ever General Staff Conference and Staff Ride at Camberley in January 1905.[56] He continued to lobby for a General Staff to be set up, especially after the Dogger Bank incident of October 1904. Repington also campaigned publicly for this from May 1905, which helped prod Brodrick’s successor Arnold-Forster into action. He asked Wilson for his views – Wilson proposed a strong Chief of the General Staff who would be the Secretary of State for War’s sole adviser on matters of strategy, ironically the position which would be held by Wilson’s rival Robertson during the First World War.[57] Despite pressure from Repington, Esher and Sir George Clarke, progress on the General Staff was very slow. In August Arnold-Forster issued a minute similar to Wilson’s of three months previous. Lyttelton (Chief of the General Staff), unaware of Wilson’s role, expressed support. In November Wilson released Arnold-Forster's memo to the press, claiming he had been ordered to do so; Arnold-Forster initially expressed “amazement” but then agreed that the leak had “done nothing but good”.[58]

The Wilsons had Christmas Dinner with Roberts (“the Chief”) in 1904 and 1905, while Roberts, whose son Freddie had been killed in the Boer War, was fond enough of Wilson to discuss his will and his wish that his daughters marry to continue the family line. Wilson assisted Roberts with his House of Lords speeches, and the closeness of their relationship attracted disapproval from Lyttelton, and possibly French and Arnold-Forster. Relations with Lyttelton became more strained in 1905-6, possibly out of jealousy or influenced by Repington.[59] Wilson had predicted a hung Parliament in January 1906, but to his disgust, “that traitor C.B.” had won a landslide.[56][60]

There was a war scare in May 1906 when the Turks occupied an old Egyptian fort at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. Wilson noted that Grierson (Director of Military Operations) and Lyttelton (“absolutely incapable … positively a dangerous fool”) had approved the proposed scheme for military action, but neither the Adjutant-General nor the Quartermaster-General had been consulted.[61] Repington wrote to Esher (19 Aug 1906) that Wilson was an “intriguing impostor” and “a low-class schemer whose sole aptitude is for worshipping rising suns – an aptitude expressed by those who know him in more vulgar language”.[62] On 12 September 1906 Army Order 233 finally set up a General Staff to supervise education and training and to draw up war plans (Wilson had drafted an Army Order late in 1905, but it had been held up by disputes over whether staff officers should be appointed by the Chief of the General Staff as Wilson preferred or by an eleven-man selection board).[61]

Commandant, Staff College

Appointment

Wilson had hoped, as early as March 1905, to succeed Rawlinson as Commandant at Staff College, Camberley, when Rawlinson told him he had been offered a brigadier-general’s staff position at Aldershot Command; however the move was postponed until the end of the year. In June 1905 Wilson learned that Arnold-Forster (Secretary of State for War) thought him the man for the job, but on 12 July Lyttelton (Chief of the General Staff), who appears to have disliked Wilson, raised the job to a brigadier-general’s position, for which Wilson was not yet senior enough.[63]

On 16 July 1906 Rawlinson told Wilson that he wanted him to succeed him at the end of the year, and the news appeared in the press in August amidst praise for Rawlinson, suggesting that he rather than Wilson had leaked it. In September and October 1906 Lyttelton favoured Colonel Edward (“Edna”) May, Assistant Director of Military Operations and described by Lord Esher as “a worthy but stupid officer”. Ewart (Director of Military Operations) and Haig (Director of Military Training) opposed May's appointment, whilst Field Marshal Roberts wrote to Richard Haldane (Secretary of State for War from December 1905) and Esher recommending Wilson on the basis of his excellent staff work in South Africa, and as a strong character needed to maintain Rawlinson’s improvements to training at Camberley. Wilson, who learned indirectly from Aylmer Haldane (cousin of Richard Haldane) on 24 October that he was to get the job, wrote to thank Roberts, and was in little doubt that his support had clinched it for him. Wilson remained very close to Roberts, often joining him for Christmas Dinner and attending his Golden Wedding in May 1909.[64] French (then commanding 1st Army Corps at Aldershot Command) had initially been suspicious of Wilson as a Roberts protégé, but now supported his candidacy, and by 1912 Wilson had become his most trusted adviser.[65]

Edmonds later (to Liddell Hart in 1937 and in his own unpublished memoirs) told an exaggerated version of these events, that Wilson had stitched up the job for himself whilst acting as Director of Staff Duties, by recommending May ("a really stupid Irishman") for the job and placing himself as the second recommendation. Tim Travers (in The Killing Ground 1987) used this story to help paint a picture of a prewar Army highly dependent on patronage for senior appointments. John Hussey, in his research into the matter, described Wilson’s appointment as “a collegiate decision about a difficult but suitable man” and dismisses Edmonds’ story as “worthless as evidence to prove anything about the structural defects of the old Army”. Keith Jeffrey argues that Travers’ argument is not entirely without substance – even if he is misinformed about this particular incident – and that Wilson’s career took place at “a transitional period” in which the Army was becoming more professionalised, so that Lyttelton was not able to use patronage to appoint May, his preferred candidate.[66]

Wilson noted in his diary (31 December 1906) that he had gone from captain to brigadier general in five years and one month.[67] He was promoted to substantive colonel on 1 January 1907[68] and his appointment as temporary brigadier-general and Commandant Staff College, Camberley was announced on 8 January 1907.[69] He was at first short of money – he had to borrow £350 to cover the expense of moving to Camberley, where his official salary was not enough to cover the cost of entertaining expected – and initially had to cut back on foreign holidays and social trips to London but after inheriting £1,300 on his father’s death in August 1907 was able to buy polo ponies and a second car in subsequent years.[67] His pay as commandant rose from £1,200 in 1907 to £1,350 in 1910.[70]

Doctrine

Wilson had argued as far back as a memo to Arnold-Forster in May 1905 that a "School of Thought" was needed. In his start-of-year speeches to students, he stressed the need for administrative knowledge ("the drudgery of staffwork"), physical fitness (in his mid-forties, Wilson was still able to keep up with much younger officers at sport), imagination, "sound judgement of men & affairs" and "constant reading & reflexion on the campaigns of the great masters". Brian Bond argued (in The Victorian Army and the Staff College) that Wilson’s “School of Thought” meant not just common training for staff officers but also espousal of conscription and the military commitment to send a BEF to France in the event of war. Keith Jeffrey argues that this is a misunderstanding by Bond: there is no evidence in Wilson’s writings to confirm that he meant the phrase in that way, although his political views were shared by many officers.[71]

Although Wilson was less obsessed about the dangers of espionage than Edmonds (then running MO5 – military intelligence), in March 1908 he had two German barbers removed as potential spies from Staff College.[72]

Wilson was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath in the June 1908 Birthday Honours.[70]

In 1908 Wilson had his senior class prepare a scheme for the deployment of an Expeditionary Force to France, assuming Germany to have invaded Belgium. Questions were asked in the House of Commons when news of this leaked out, and the following year no assumption was made of a German invasion of Belgium, and students were sharply reminded that the exercise was “SECRET”.[73] Wilson first met Foch on a visit to the Ecole Superieur de Guerre (December 1909, and again on Wilson’s way home from holiday in Switzerland in January 1910). They struck up a good rapport, and both thought the Germans would attack between Verdun and Namur (in the event they would attack much further west than that).[74][75] Wilson arranged for Foch and Victor Huguet to visit Britain in June 1910, and copied his practice of setting students outdoor exercises in which they were distracted by instructors shouting “Allez! Allez!” and “Vite! Vite!” at them whilst they were attempting to draw up plans at short notice.[74]

Accompanied by Colonel Harper Wilson reconnoitred the likely future theatre of war. In August 1908, along with Edward Percival (“Perks”), they explored south of Namur by train and bicycle. In August 1909 Harper and Wilson travelled from Mons then down the French frontier almost as far as Switzerland. In Spring 1910, this time by motor car, they travelled from Rotterdam into Germany, then explored the German side of the frontier, noting the new railway lines and “many sidings” which had been built near St Vith and Bitburg (to allow concentration of German troops near the Ardennes).[76][77]

Wilson privately supported conscription at least as early as 1905. He thought Haldane’s scheme to merge Militia, Yeomanry and Volunteers into a new Territorial Army of 16 divisions would not be enough to match German training and efficiency. He was summoned to see Haldane (March 1909) after an article in the Liberal Westminster Gazette (inspired by Repington, Wilson assumed) claimed that he supported conscription. In a lecture to students (November 1909) he did not publicly oppose government policy but hinted that it might not be enough. His wife Cecil organised a National Service League meeting that month.[78] Wilson successfully (November 1907) lobbied Haldane for an increase in the size of the Staff College in order to provide trained staff officers for the new Territorial Army. Haldane agreed an expansion after an inspection in March 1908. During Wilson’s tenure the number of instructors rose from 7 to 16 and the number of students from 64 to 100. In total, 224 Army and 22 Royal Navy officers studied under him.[70]

Wilson voted for Parliament for the first time in January 1910 (for the Unionists).[79][80] He recorded that “the lies told by the Radicals from Asquith down are revolting”.[81]

Lecturing style

Launcelot Kiggell wrote that he was a “spell-binding” lecturer as Commandant at Camberley.[8] During his time as Commandant Wilson gave 33 lectures. A number of students, of whom the most famous was Archibald Wavell, later contrasted Wilson’s expansive lecturing, ranging widely and wittily over geopolitics, with the more practical focus of his successor Robertson. Many of these recollections are unreliable in their details, may well exaggerate the differences between the two men, and may have been influenced by Wilson’s indiscreet diaries published in the 1920s.[82]

Berkeley Vincent, who had been an observer in the Russo-Japanese War (he was a protégé of Ian Hamilton, whom Wilson appears to have disliked), took a more critical view of Wilson. He objected to Wilson’s tactical views – Wilson was sceptical of claims that Japanese morale had enabled their infantry to overcome Russian defensive firepower – and his lecturing style: “a sort of witty buffoonery … a sort of English stage Irishman”.[83]

Succession

In May and June 1909 Wilson had been tipped to succeed Haig as Director of Staff Duties, although he would have preferred command of a brigade.[70] In April and May 1910, with his term of office at Camberley still officially running until January 1911, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), William Nicholson, told Wilson that he was to succeed Spencer Ewart as Director of Military Operations that summer and vetoed him from accepting Horace Smith-Dorrien’s offer of a brigade at Aldershot.[84] King George V rounded off Wilson's tenure at Camberley in style with an official visit in July 1910.[70]

Wilson recommended Kiggell as his successor and thought the appointment of William Robertson “a tremendous gamble”, writing “my heart sinks when I think what it all may mean to the College & this house”. He may have felt that Robertson’s lack of private means did not suit him for a position which required entertaining.[85] Robertson visited Camberley with Lord Kitchener (28 July 1910), who criticised Wilson; this may have been one of the causes of the poor relations between Wilson and Kitchener in August 1914.[86] Edmonds later told a story of how Wilson had, perhaps as a joke or wanting to draw attention to Robertson’s shortage of money, left a bill for £250 for furniture and improvements to the Commandant’s residence, and that Wilson’s predecessor Rawlinson, when approached by Robertson for advice, had been amused and had commented that many of these improvements had been made by his own wife or by previous Commandants. Whatever the truth of the matter, relations between Wilson and Robertson deteriorated thereafter.[87]

Repington (whom Wilson thought a “dirty brute” and “lying brute”) attacked the current standards of British staff officers in The Times on 27 September 1910, arguing that Wilson had educated staff officers to be “sucking Napoleons” and that Robertson was a “first rate man” who would sort it out.[88] Wilson wrote to Lord Loch (27 September 1910) “we can comfort ourselves with the reflexion that to be abused by Repington is the highest praise an honest man can get”.[89]

Director of Military Operations

Initial decisions

In 1910 Wilson became Director of Military Operations at the British War Office.[77][90] As DMO Wilson headed a staff of 33, divided into five sections: MO1 was “Strategic & Colonial”, MO2 “European, MO3 “Asiatic”, and the others were “Geographic” and “Miscellaneous”. He was initially impressed only by the mapping section (and one of his first acts was to have a huge map of the Franco–German frontier hung on his office wall). He soon restructured the sections into MO1 (responsible for the forces of the Crown, including those in India; the Territorial Army was deemed part of Home Defence and answered to the Director of Military Training), MO2 (France and Russia) and MO3 (the Triple Alliance).[91]

Wilson believed his most important duty as DMO to be the drawing up of detailed plans for deployment of an expeditionary force to France, in accordance with the CID’s decision of July 1909. Little progress had been made in this area since Grierson’s plans during the First Moroccan Crisis.[8][92] Maj-Gen Spencer Ewart (Grierson’s successor as DMO) and William Nicholson (CIGS) had both avoided direct dealings with Victor Huguet, the French Military attache.[93] Of the 36 papers which Wilson wrote as DMO, 21 were taken up by matters pertaining to the Expeditionary Force. He hoped also to get conscription brought in, but this came to nothing.[94]

Wilson described the size of Haldane’s planned Expeditionary Force (six divisions of three brigades each and a cavalry division of four brigades) as simply a “reshuffle” of the troops available in Britain, and often declared that “there was no military problem to which the answer was six divisions”. Foch is supposed to have told Wilson that he would be happy for Britain to send just a corporal and four men, provided it was right from the start of the war, and that he promised to get them killed, so that Britain would come into the war with all her strength.[95] Foch, recently returned from a visit to Russia, was concerned that France might not be able to count on Russian support in the event of war, and was more keen than ever to enlist British military aid. He invited Wilson and Colonel Fairholme, British military attaché in Paris, to his daughter’s wedding in October 1910. On a visit to London (6 December 1910) Wilson took him for a meeting with Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent-Under Secretary at the Foreign Office.[96]

In 1910 Wilson bought 36 Eaton Place on a 13 year lease for £2,100. His salary was then £1,500. The house was a financial burden and the Wilsons often let it out.[97]

Wilson and his staff spent the winter of 1910–11 conducting a "great strategical War Game" to predict what the great powers would do when war broke out.[91]

Early 1911

Wilson thought the existing plans for deployment of the BEF (known as the "WF" scheme – this stood for "With France" but was sometimes wrongly thought to stand for "Wilson-Foch") "disgraceful. A pure academic, paper arrangement of no earthly value to anyone." He sent Nicholson a long minute (12 January 1911) demanding authority to take transport planning in hand. He was given this after a lunch with Haldane, who had already consulted Foreign Secretary Grey (20 January).[98]

In 27–8 January 1911 Wilson visited Brussels, dining with members of the Belgian General Staff, and later exploring the part of the country south of the Meuse with the military attaché Colonel Tom Bridges.[99] Between 17–27 February he visited Germany, meeting Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and Admiral Tirpitz at a dinner at the British Embassy. On the return journey he noted how many railway sidings were being built at Herstal on the Belgian frontier, and dined in Paris with Foch, whom he warned (26 February) against listening to Repington, and the French Chief of Staff General Laffort de Ladibat.[89] Admiral John Fisher (letter to J.A.Spender 27 February 1911) was hostile to Wilson’s plans to deploy forces to the continent.[100] By 21 March Wilson was preparing plans to embark the BEF infantry by Day 4 of mobilisation, followed by the cavalry on Day 7 and the artillery on Day 9.[101]

Refusing Nicholson’s request (April 1911) that he help with Repington’s new Army Review, he declared him “a man devoid of honour, & a liar”.[89] He warned Robinson of The Times (24 May) against listening to him.[89]

Second Moroccan crisis

Wilson sat up till midnight on 4 July (three days after the Panther arrived at Agadir in an attempt to overawe the French) writing a long minute to the CIGS. On 19 July he went to Paris for talks with Adolphe Messimy (French War Minister) and General Dubail (French Chief of Staff). The Wilson-Dubail memorandum, although making explicit that neither government was committed to action, promised that in the event of war the Royal Navy would transport 6 infantry and 1 cavalry divisions (150,000 men) to Rouen, Le Havre and Boulogne, and that the BEF would concentrate between Arras, Cambrai and St Quentin by the thirteenth day of mobilisation. In reality, the transport plans were nowhere near ready, although it is unclear that the French knew this.[102][103] The French called the Expeditionary Force “l’Armee Wilson”[104] although they seem to have been left with an inflated idea of the size of commitment which Britain would send.[105]

Wilson approved of Lloyd George’s Mansion House speech (backing France), which he thought preferable to "the funk Edward Grey('s) procrastinat(ion)".[106] He lunched with Grey and Sir Eyre Crowe (Assistant Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office) on 9 August, urging them that Britain must mobilise on the same day as France and send the whole six divisions. He thought Grey “the most ignorant & careless of the two … an ignorant, vain & weak man quite unfit to be the Foreign Minister of any country larger than Portugal”. Wilson was perhaps unappreciative that Grey was not only trying to find a peaceful resolution but also had to consider the domestic political crisis as the Parliament Act was being pushed through and troops were being deployed against strikers in London,[107] Liverpool and South Wales.[108]

CID meeting

Hankey (letter to McKenna 15 August 1911) complained of Wilson’s “perfect obsession for military operations on the Continent”, scoffing at his bicycling trips and accusing him of filling the War Office with like-minded officers.[109] At Nicholson’s request Wilson prepared a paper (dated 15 August), based on the evolution of his ideas over the previous ten years. He argued that British aid would be necessary to prevent Germany defeating France and achieving domination of the continent, and that this would have both a moral and a military effect on the outcome. He argued that by Day 13 of mobilisation France would have the upper hand, outnumbering the Germans by 63 divisions to 57 along the frontier, but by Day 17 Germany would outnumber France by 96 divisions to 66. However, because of road bottlenecks in the passable parts of the war theatre, the Germans would at most be able to deploy 54 divisions in the opening phase, allowing the 6 infantry divisions of the BEF a disproportionate effect on the outcome. Ernest May (in Knowing One’s Enemies: Intelligence Assessments Between the Two World Wars 1984) later claimed that Wilson had “cooked” these figures, but his arguments were challenged by Edward Bennett, who argued that Wilson’s numbers were not far wrong (Journal of Modern History, June 1988).[110]

This became the General Staff position for the CID meeting on 23 August. This was attended by Cabinet Ministers Asquith, Haldane, McKenna, Churchill, Grey, Lloyd George, as well as Nicholson (CIGS), French (the likely commander of the BEF) and Wilson representing the Army, and Sir Arthur Wilson (First Sea Lord) and Alexander Bethell (Director of Naval Intelligence). Admiral Wilson gave a poor account of himself, proposing that 5 divisions guard Britain whilst one land on the Baltic coast, or possibly at Antwerp, believing that the Germans would be halfway to Paris by the time an Expeditionary Force was ready, and that the four to six divisions Britain was expected to be able to muster would have little effect in a war with 70-80+ divisions on each side. Wilson thought the Royal Navy plan “one of the most childish papers I ever read”.[111] Henry Wilson set out his own plans, apparently the first time the CID had heard them.[77] Hankey recorded that Wilson’s lucid presentation carried the day even though Hankey himself did not entirely agree with it. Prime Minister H.H. Asquith ordered the Navy to fall in with the Army’s plans, although he preferred to send only four divisions. Hankey also recorded that even by 1914 French and Haig were not fully aware of what had been decided, Morley and Burns resigned from the Cabinet as they were unable to accept the decision, and Churchill and Lloyd George never fully accepted the implications of committing a large military force to France. After the meeting Hankey began to draw up the War Book detailing mobilisation plans, and yet the exact deployment of the BEF was still undecided as late as 4 August 1914.[104]

Wilson had recommended deploying at Maubeuge. He thought (wrongly, as it turned out) that the Germans would only violate Belgian territory south of the Meuse, whereas to attack further north would mean attacking Liege, Huy and Namur, possibly violating Dutch neutrality by crossing the Maastricht appendix, and would be more likely to attract Belgian resistance. Over the next few weeks Wilson had several meetings with Churchill (one of which lasted three hours), Grey and Lloyd George, who were keen to obtain an agreement with Belgium. This attracted the opposition of Haldane, who wrote to Churchill that Wilson was “a little impulsive. He is an Irishman & … knows little of the Belgian Army”, and Nicholson, who suppressed a lengthy paper by Wilson (20 September 1911) arguing for an agreement with Belgium; the paper was eventually circulated to the CID by Nicholson's successor Sir John French in April 1912.[112]

Late 1911

Throughout the Agadir Crisis Wilson was keen to pass on the latest intelligence to Churchill, e.g. that the Germans were deploying two divisions near Malmedy on the German-Belgian frontier, or were buying up stocks of wheat. Churchill and Grey came to Wilson’s house (4 September) to discuss the situation until after midnight. Wilson (18 September) recorded four separate reports from spies of German troops massing opposite the Belgian frontier. Wilson was also responsible for Military Intelligence, then in its infancy. This included MO5 (under George Macdonogh, succeeding Edmonds) and the embryonic MI5 (under Colonel Vernon Kell) and MI6 (under “C”, Commander Mansfield Cumming). It is unclear from the surviving documents just how much of Wilson’s time was taken up by these agencies, although he dined with Haldane, Kell and Cumming on 26 November 1911.[113]

In October 1911 Wilson went on another bicycle tour of Belgium south of the Meuse, also inspecting the French side of the frontier, also visiting Verdun, the battlefield of Mars-La-Tour, where he claimed to have laid (16 October) a small map showing the planned concentration areas for the BEF at the foot of the statue of France, then Fort St Michel at Toul (near Nancy). On his way home, still keen to “snaffle these Belgians” he visited the British military attaché in Brussels.[114][115]

Radical members of the Cabinet (Morley, McKenna, Crewe, Harcourt) pushed for Wilson’s removal, but he was staunchly defended by Haldane (16–18 November 1911), who had the backing of the most influential ministers: Asquith, Grey and Lloyd George, as well as Churchill.[116]

1912

After Agadir the MO1 section under Harper became a key branch in preparing for war. Churchill, newly appointed to the Admiralty, was more receptive to Army-Navy cooperation. Intelligence suggested (8 January) that Germany was getting ready for war in April 1912.[116] In February 1912 Wilson inspected the docks at Rouen, had meetings in Paris with Joffre, de Castelnau and Millerand (War Minister), visited Foch, now commanding a division at Chaumont, and inspected southern Belgium and the Maastricht appendix with Major Sackville-West (“Tit Willow”) who had been on his directing staff at Camberley and now worked at MO2.[117] Sir John French, the new CIGS (March 1912), was receptive to Wilson’s wishes to prepare for war and to cooperate with Belgium, although in the end the Belgian Government refused to cooperate and remained strictly neutral until the outbreak of war,[118] with the Belgians even deploying a division in 1914 to guard against British violation of Belgian neutrality.[119] In April Wilson played golf at Ostend for two days with Tom Bridges, briefing him for talks with the Belgians, whom Wilson wanted to strengthen Liege and Namur.[120]

Through his brother Jemmy, Wilson forged links with the new Conservative leader Bonar Law. Jemmy had been on the platform in Belfast in April 1912 when Law addressed a mass meeting against Home Rule, and in the summer of 1912 he came to London to work for the Ulster Defence League (run by Walter Long and Charlie Hunter).[121] At Charlie Hunter’s suggestion, Wilson dined with Law (23 June 1912). He was impressed by him and spent an hour and three quarters discussing Ireland and defence matters. That summer he began having regular talks with Long, who used Wilson as a conduit to try to establish cross-party defence agreement with Churchill.[121]

Wilson (September 1912) thought Haldane a fool for thinking that Britain would have a time window of up to six months in which to deploy the BEF.[120] In September 1912 he inspected Warsaw with Alfred Knox, British military attaché in Russia, then met Zhilinsky in St Petersburg, before visiting the battlefield of Borodino, and Kiev, then – in Austria-Hungary – Lemburg, Krakow and Vienna. Plans to visit Constantinople had to be shelved because of the First Balkan War, although Wilson recorded his concerns that the Bulgars had beaten the Turks a month after the declaration of war – evidence that the BEF must be committed to war at once, not within six months as Haldane hoped.[120]

By 14 November 1912 the railway timetables, drawn up by Harper’s MO1, were ready, after two years of work. A joint Admiralty-War Office committee, including representatives of the merchant shipping industry, met fortnightly from February 1913, and produced a workable scheme by spring 1914. In the event the transport of the BEF from just three ports (Southampton for troops, Avonmouth for mechanical transport and Newhaven for stores) would proceed smoothly.[118] Brian Bond argued that Wilson’s greatest achievement as DMO was the provision of horses and transport and other measures which allowed mobilisation to proceed smoothly.[122]

Repington and Wilson were still cutting one another dead whenever they met. In November 1912 Repington, who wanted to use the Territorial Army as a basis for conscription, urged Haldane (now Lord Chancellor) to have Wilson sacked and replaced by Robertson.[123]

Wilson again gave evidence to the CID (12 November 1912) that the presence of the BEF on the continent would have a decisive effect in any future war.[123]

In 1912 Wilson was appointed Honorary Colonel of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles.[124]

1913

Wilson’s support for conscription made him friendly with Leo Amery, Arthur Lee, Charlie Hunter, Earl Percy, (Lord) Simon Lovat, Garvin of The Observer, Gwynne of The Morning Post and F.S Oliver, owner of the Department Store Debenham and Freebody. Wilson briefed Oliver and Lovat, who were active in the National Service League. In December 1912 Wilson cooperated with Gwynne and Oliver in a campaign to destroy the Territorial Force.[125]

In the spring of 1913 Roberts, after previous urging by Lovat, arranged a reconciliation between Repington and Wilson. Repington wrote a letter to The Times in June 1913, demanding to know why Wilson was not playing a more prominent role in the CID “Invasion Inquiry” (debates of 1913–14 as to whether some British regular divisions should be retained at home to defeat a potential invasion).[123] In May 1913 Wilson suggested that Earl Percy write an article against the “voluntary principle” for the National Review and helped him write it. He was also drafting pro-conscription speeches for Lord Roberts. Although Roberts was not a “whole hogger” – he favoured conscription only for home defence, not a full-scale conscript army on the continental model – Wilson advised other campaigners not to quarrel with him and risk losing his support.[125]

Wilson visited France seven times in 1913, including a visit in August with French and Grierson to observe French manoeuvres at Chalons, and Foch's XX Corps manoeuvres in September. Wilson spoke French fluently but not perfectly, and would sometimes revert into English for sensitive matters in order not to risk speaking inaccurately.[126]

In October 1913 Wilson visited Constantinople, in the company of Charlie Hunter MP. He saw the lines of Charaldhza, and the battlefields of Lule Burgaz and Adrianople. Wilson was unimpressed by the Turkish Army and road and rail infrastructure, and felt that the introduction of constitutional government would be the final blow to the Ottoman Empire. These views, although correct in the long term, may have contributed to the underestimation of Turkey’s defence strength at Gallipoli.[127]

Roberts had been lobbying French to promote Wilson to major-general, a rank appropriate to his job as DMO, since the end of 1912. In April 1913, with a brigade command about to fall vacant, Wilson was assured by French that he was to be promoted to major-general later in the year, and that not having commanded a brigade would not prevent him commanding a division later.[128] Even before leaving the field of the manoeuvres (26 September 1913), French told Wilson that he was not satisfied with Grierson’s performance. Wilson believed that French wanted him to become chief of staff designate of the BEF after the 1913 manoeuvres, but that he was too junior. Instead Murray was appointed.[129]

Wilson was promoted major general in November 1913.[130] French confided that he intended to have his own term as CIGS extended by two years to 1918, and to be succeeded by Murray, at which point Wilson was to succeed Murray as sub-CIGS.[128] After a 17 November 1913 meeting of BEF senior officers (French, Haig, Wilson, Paget, Grierson), Wilson privately recorded his concerns at French’s lack of intellect and hoped there would not be a war just yet.[131]

Early in 1914, at an exercise at Staff College, Wilson acted as Chief of Staff. Edmonds later wrote that Robertson, acting as Exercise Director, drew Wilson’s attention to his ignorance of certain procedures, and said to French in a stage whisper “if you go to war with that operations staff, you are as good as beaten” [132]

Curragh incident

Family political tradition

Wilson and his family had long been active in Unionist politics. His father had stood for Parliament for Longford South in 1885, whilst his older brother James Mackay (“Jemmy”) had stood against Justin McCarthy for Longford North in 1885 and 1892, being defeated by a margin of over 10:1 each time.[133]

As far back as 1893, during the passage of Gladstone’s Second Home Rule Bill, Wilson had been party to a proposal to raise 2,000–4,000 men, to drill as soldiers in Ulster, although he wanted Catholics also to be recruited. In February 1895 Henry and Cecil listened to and “enjoyed immensely” a “very fine” speech by Joseph Chamberlain about London municipal questions in Stepney, and Wilson listened to another speech by Chamberlain in May. In 1903 Wilson’s father was part of the Landowners’ Convention deputation to observe the passage of Irish land legislation through Parliament. In 1906 his younger brother Tono was Tory agent in Swindon.[134]

Crisis brews

Wilson supported Ulster Unionist opponents of the Third Irish Home Rule Bill, which was due to become law in 1914.[1] Wilson had learned from his brother Jemmy (13 April 1913) about plans to raise 25,000 armed men and 100,000 “constables”, and to form a Provisional Government in Ulster to take control of banks and railways, which he thought “all very sensible”. It is unclear whether he actually envisaged armed insurrection or hoped that the Government would back off. Asked by Roberts (16 April 1913) to be chief of staff to the “Army of Ulster”, Wilson replied that if necessary he would fight for Ulster rather than against her.[135]

At a meeting at the War Office (4 November 1913), Wilson told French, who had recently been asked by the King for his views, that he for one “could not fire on the north at the dictates of Redmond” and that “England qua England is opposed to Home Rule, and England must agree to it … I cannot bring myself to believe that Asquith will be so mad as to employ force”. It is unclear what Wilson meant by "England qua England", although he did believe that the Government should be forced to fight a General Election on the issue, which on the basis of recent by-elections the Conservatives might win. Each side thought the other was bluffing. French, whom Wilson urged to tell the King that he could not depend on the loyalty of the whole of the Army, was unaware that Wilson was leaking the contents of these meetings to the Conservative leader Bonar Law.[136][137]

Wilson (diary 6, 9 November) met Bonar Law and told him that he did not agree that the percentage of defections in the officer corps would be as high as 40%, the figure suggested by the King’s adviser Lord Stamfordham. He passed on his wife Cecil’s advice that the UVF should take the patriotic high ground by pledging to fight for King and Country in the event of war.[138] Cecil, whose family had lost its livelihood in the nineteenth century, may well have felt more strongly about Ireland than Wilson himself.[139] Bonar Law immediately attempted to reach Carson on the telephone to relay this suggestion. Wilson also advised Bonar Law – at this time the government were attempting to offer Counties Londonderry, Antrim, Armagh and Down an opt-out from Home Rule, the plan being that a refusal would make Carson look intransigent – to ensure that negotiations failed in way which made the Irish Nationalists look intransigent.[140]

He met Macready, Director of Personal Services, who told him (13 Nov) that he was being sent over to Ulster but that the Cabinet would not try to deploy troops. On 14 November he dined with Charlie Hunter and Lord Milner, who told him that any officers who resigned over Ulster would be reinstated by the next Conservative Government. Wilson also warned Edward Sclater (15 November) that the UVF should not take any action hostile to the Army. Wilson found Asquith’s Leeds speech – in which the Prime Minister promised to “see this thing through” without an election – “ominous”, and on 28 November John du Cane turned up at the War Office “furious” with Asquith and asserting that Ulster would have to be granted Belligerent status like the Confederate States of America.[139]

The Wilson and Rawlinson families spent Christmas with Lord Roberts, who was strongly opposed to the planned legislation, as was Brigadier Johnnie Gough, with whom Wilson played golf on Boxing Day, as was Leo Amery with whom he lunched at White's on New Year’s Day. Wilson’s main concern was “that the army should not be drawn in”, and on 5 January he had “a long and serious talk about Ulster & whether we couldn’t do something to keep the Army out of it” with Joey Davies (Director of Staff Duties since October 1913) and Robertson (Director of Military Training), and the three men agreed to take soundings of army opinion at the annual Staff College conference at Camberley the following week. At the end of February Wilson went to Belfast, where he visited the Unionist Headquarters at Old Town Hall. His mission was not secret – the official purpose was to inspect 3rd Royal Irish Rifles and give a lecture on the Balkans at Victoria Barracks, and he reported his opinion of the Ulster situation to the Secretary of State and to Sir John French – but attracted press speculation (5 March).[141] Wilson was delighted by the Ulster Volunteers (now 100,000 strong),[142] to whom he was also leaking information.[143]

The incident

After Paget had been told to prepare to deploy troops in Ulster, Wilson attempted in vain to persuade French that any such move would have serious repercussions not only in Glasgow but also in Egypt and India.[144] Wilson helped the elderly Lord Roberts (morning of 20 March) draft a letter to the Prime Minister, urging him not to cause a split in the army. Wilson was summoned home by his wife to see Johnnie Gough, who had come up from Aldershot, and told him of Hubert Gough’s threat to resign (see Curragh Incident). Wilson advised Johnnie not to “send in his papers” (resign) just yet, and telephoned French, who when told of the news “talked windy platitudes till (Wilson) was nearly sick”.[145][146]

By the morning of Saturday 21 Wilson was talking of resigning and urging his staff to do the same, although he never actually did so and forfeited respect by talking too much of bringing down the government.[147][148] With Parliament debating a Conservative motion of censure on the government for using the Army in Ulster,[148] Repington telephoned Wilson (21 April 1914) to ask what line The Times should take.[123] Fresh from a visit to Bonar Law (21 March), Wilson suggested prodding Asquith to take “instant action” to prevent general staff resignations. At the request of Seely (Secretary of State for War) Wilson wrote a summary of “what the army would agree to”, namely a promise that the army would not be used to coerce Ulster, but this was not acceptable to the government. Despite Robertson’s warm support, Wilson was unable to persuade French to warn the government that the Army would not move against Ulster.[149]

Hubert Gough breakfasted with Wilson on 23 March, before his meeting with French and Ewart at the War Office, where he demanded a written guarantee that the Army would not be used against Ulster.[150] Wilson was also present at the 4pm meeting at which Gough, on his advice, insisted on amending a Cabinet document to clarify that the Army would not be used to enforce Home Rule on Ulster, to which French also agreed in writing. Wilson then left, telling people in the War Office that the Army had done what the Opposition had failed to do (i.e. prevent the coercion of Ulster). Wilson told French that he suspected he (French) would be sacked by the Government, in which case "the Army would go solid with him".[151] To his brother’s amusement, Johnnie Gough “hotted” (teased) Wilson by affecting to believe that he was actually going to resign.[152] Wilson was worried that a future Dublin government might issue “lawful orders” to coerce Ulster. At the top of his diary page for 23 March he wrote: “We soldiers beat Asquith & his vile tricks”.[153]

Asquith publicly repudiated the amendments to the Cabinet document (the "peccant paragraphs") (25 March), but at first refused to accept the resignations of French and Ewart, although Wilson advised French (mid-afternoon on 26 March) that he must resign "unless they were in a position to justify their remaining on in the eyes of officers". French eventually resigned after Wilson tested the climate at a Staff College point-to-point.[143][154]

Effects

Wilson telegraphed Gough twice and advised him to "stand like a rock" and hold onto the document, but received no reply to either telegram. Milner thought Wilson had “saved the Empire”, which Wilson (29 March) thought “much too flattering”. He thought (29 March) Morley (who had advised Seely) and Haldane (who advised French) would also have to resign, which would bring down the government. Gough was angry that Wilson had not himself offered to resign and (Soldiering On p171) blamed Wilson for having done nothing to stop the government’s plans to coerce Ulster until Gough and his officers threatened to resign.[147] The Gough brothers thereafter cut Wilson, and Johnnie Gough never spoke to Wilson again.[143][154][155] The young Captain Archibald Wavell, then working at the War Office, wrote to his father that although he disapproved of the ultimatum which had been put to Gough and his officers by Paget, nonetheless he was disgusted by Wilson’s blatant meddling in party politics and talk of bringing down the government.[156]

Between 21 March and the end of the month, Wilson saw Law nine times (although he declined an invitation to dine with Law, Balfour and Austen Chamberlain on 22 March), Amery four times, Gwynne three times, and Milner and Arthur Lee twice. He does not seem to have regarded these contacts with the Opposition as particularly secret. Roberts was also leaking information which he was being fed by Wilson and the Gough brothers, whilst French was seeing Gwynne most days. Gough promised to keep the 23 March Treaty confidential, but it soon leaked to the press – it appears that both Gough and French leaked it to Gwynne, whilst Wilson leaked it to Amery and Bonar Law.[157]

First World War

1914

Outbreak of war

Wilson visited France four times to discuss war plans between January and May 1914. With the CID having recommended that two of the BEF's six divisions be retained at home to guard against invasion in the event of war, Wilson successfully lobbied Asquith, who was Secretary of State for War since the Curragh Incident, to send at least five divisions to France (6 May 1914).[158]

During the July Crisis Wilson was mainly preoccupied with the apparent imminence of civil war in Ireland, with Carson unwilling to accept anything less than complete exclusion of the Six Counties, and vainly lobbied the new CIGS Charles Douglas to flood the whole of Ireland with troops (29 June). By the end of July it was clear that the continent was on the brink of hostilities, with Wilson being lobbied by Milner and the diplomat Eyre Crowe about Edward Grey’s reluctance to go to war.[159] Wilson (1 August) called on de la Panouse (French Military Attache) and Paul Cambon (French Ambassador) to discuss the military situation.[160] Wilson may well have been keeping the Conservative leadership informed of discussions between Cambon and Foreign Secretary Grey.[161][162] The German invasion of Belgium provided a casus belli and Britain mobilized on 3 August and declared war on 4 August.[163]

Once the decision for war had been taken, Wilson promised de la Panouse that Britain would honour Asquith’s decision to send five divisions to France.[160] Wilson was present at the War Council (a meeting of politicians and military men on 5 August) at which Sir John French proposed deploying the BEF to Antwerp (Wilson had already argued against this as impractical), and Haig proposed holding it back for two or three months until more troops could be sent. After debate about whether to deploy the BEF to Maubeuge, Amiens or Antwerp, which Wilson likened to “our discussing strategy like idiots”, it was decided to deploy five divisions to Maubeuge. The following day Kitchener scaled back this commitment to four divisions and lobbied to deploy them to Amiens.[164][165]

Sub Chief of Staff, BEF: deployment

Wilson was initially offered the job of "Brigadier-General of Operations" but as he was already a major-general he negotiated an upgrade in his title to "Sub Chief of Staff".[166] Edmonds, Kirke (in his memoir of Macdonogh) and Murray all claimed after the war that French had wanted Wilson as Chief of Staff, but this had been vetoed because of his role in the Curragh Mutiny, but there is no contemporary evidence, even in Wilson’s diary, to confirm this.[167]

Wilson met with Victor Huguet (7 August), a French liaison officer summoned to London at Kitchener’s request, and sent him back to France to obtain more information from Joffre, having told him of British plans to start movement of troops on 9 August. Kitchener, angry that Wilson had acted without consulting him, summoned him to his office for a rebuke. Wilson was angry that Kitchener was confusing the mobilisation plans by deploying troops from Aldershot to Grimsby in case of German invasion, and recorded in his diary that "I answered back as I have no intention of being bullied by him especially when he talks such nonsense … the man is a fool … He is a d---- fool". On Huguet's return (12 August) he met with French, Murray and Wilson. They agreed to deploy the BEF to Maubeuge, but Kitchener, in a three-hour meeting which was, according to Wilson, "memorable in showing K’s colossal ignorance and conceit", tried to insist on a deployment to Amiens where the BEF would be in less danger of being overrun by the Germans coming north of the Meuse.[168] Wilson wrote not just of the difficulties and delays which Kitchener was making but also of “the cowardice of it”, but there is little doubt that Kitchener was correct.[169] The clash of personalities between Wilson and Kitchener worsened relations between Kitchener and Sir John French, who often took Wilson's advice.[170]

Wilson, French and Murray crossed to France on 14 August.[171] Wilson was sceptical of the German invasion of Belgium, feeling that it would be diverted to meet the French thrusts into Lorraine and the Ardennes.[172] Reconnoitring the area with Harper in August 1913, Wilson had wanted to deploy the BEF just east of Namur. Although Wilson's prediction of the German advance was less prescient than Kitchener's, had this been done, it is possible that Anglo-French forces could have attacked north, threatening to cut off the German Armies moving westwards north of the Meuse.[171]

Like other British commanders Wilson at first underestimated the size of German forces opposite the BEF, although Terraine and Holmes are very critical of the advice which Wilson was giving Sir John on 22 August, encouraging further BEF advances and “calculating” that the BEF was faced only by one German corps and a cavalry division, although Macdonogh was providing more realistic estimates.[173][174] Wilson even issued a rebuke to the Cavalry Division for reporting that strong German forces were heading on Mons from Brussels, claiming that they were mistaken and only German cavalry and Jaegers were in front of them.[175]

.jpg)

On 23 August, the day of the Battle of Mons, Wilson initially drafted orders for II Corps and the cavalry division to attack the following day, which Sir John cancelled (after a message was received from Joffre at 8pm warning of at least 2 ½ German corps opposite[176] – there were in fact three German corps opposite the BEF with a fourth moving around the British left flank, and then a retreat was ordered at 11pm when news came that Lanrezac’s Fifth Army on the right was falling back). On 24 August, the day after the battle, he bemoaned that no retreat would have been necessary had the BEF had 6 infantry divisions as originally planned. Terraine describes Wilson's diary account of these events as “a ridiculous summary … by a man in a responsible position”, and argues that although Kitchener’s fears of a German invasion of Britain had been exaggerated, his consequent decision to hold back two divisions saved the BEF from a greater disaster which might have been brought on by Wilson's overconfidence.[173][174][177]

Sub Chief of Staff, BEF: retreat

The BEF staff, who had not rehearsed their roles, performed poorly over the next few days. Various eyewitnesses reported that Wilson was one of the calmer members of GHQ, but he was concerned at Murray's medical unfitness and French’s apparent inability to grasp the situation. Wilson opposed Smith-Dorrien’s decision to stand and fight at Le Cateau (26 August).[174] However, when told by Smith-Dorrien – Wilson had had to travel to the nearest village, his gaiters still unfastened, to use a public telephone – that it would not be possible to break off and fall back until nightfall, by his own account he wished him luck and congratulated him for his cheerful tone.[178] Smith-Dorrien's slightly different recollection was that Wilson had warned that he risked another Sedan.[179]

Baker-Carr recalled Wilson standing in dressing gown and slippers uttering “sardonic little jests to all and sundry within earshot” as GHQ packed up to evacuate, behaviour which historian Dan Todman comments was probably “reassuring for some but profoundly irritating for others”.[180] Macready recorded Wilson (27 August) “walking slowly up and down” the room at Noyon which had been commandeered as headquarters with a “comical, whimsical expression”, clapping his hands and chanting “We shall never get there, we shall never get there … to the sea, to the sea, to the sea”, although he also recorded that this was probably intended to keep up the spirits of more junior officers. His infamous “sauve qui peut” order to Snow, GOC 4th Division, (27 August) ordering unnecessary ammunition and officers’ kits to be dumped so that tired and wounded soldiers could be carried, was, according to Swinton, probably intended out of concern for the soldiers rather than out of panic. Smith-Dorrien was later rebuked by French for countermanding it.[174][181] Lord Loch thought the order showed “GHQ had lost their heads” whilst General Haldane thought it “a mad order” (both in their diaries for 28 August).[182] Major-General Pope-Hennessey later alleged (in the 1930s) that Wilson had ordered the destruction of orders issued during the retreat to hide the degree of panic.[183]