Staten Island Tunnel

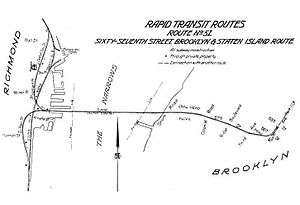

The 1912 plans of the Staten Island Tunnel to link the Staten Island Railroad to the BMT Fourth Avenue Line. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Brooklyn-Richmond Freight and Passenger Tunnel[1] |

| Line |

BMT Fourth Avenue Line IND Culver Line Staten Island Railway |

| Location | New York City |

| Status | Unfinished |

| System | New York City Subway |

| Start | Bay Ridge, Brooklyn |

| End | St. George or Tompkinsville, Staten Island |

| Operation | |

| Constructed | 1923 to 1925 |

| Traffic | Rapid Transit |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | Arthur S. Tuttle[1] |

| Length | 10,400 feet (planned) |

| Width | 24 feet (7.3 m) |

The Staten Island Tunnel is an abandoned, incomplete railway/subway tunnel in New York City. It was intended to connect railways on Staten Island (precursors to the modern-day Staten Island Railway) to the BMT Fourth Avenue Line of the New York City Subway, in Brooklyn, via a new crossing under the Narrows. Planned to extend 10,400 feet (3,200 m), the tunnel would have been among the world's longest at the time of its planning, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Construction began in 1923, but New York City Mayor John Hylan, a former Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) employee, canceled the project, and the tunnel only went 150 feet (46 m) into the Narrows before it was halted. The tunnel lies dormant under Owl's Head Park in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Later proposals to complete the tunnel, including the 1939 plans for the Independent Subway System's ambitious Second System, were never funded.

Modern proposals for completion of the tunnel have come from New York City Councilman Lewis Fidler, who has proposed 0.33% tax for the tri-state region to pay for the construction. The tunnel was listed as one of many projects that could receive federal funds that were to have been allocated to the Access to the Region's Core tunnel, which was canceled in October 2010. State Senator Diane Savino was among the supporters of the tunnel; Savino stated that if built, the tunnel would cost $3 billion and would improve quality of life for Staten Islanders, reduce traffic, and increase the attractiveness of the borough for investment.

Other names

Officially called the Brooklyn-Richmond Freight and Passenger Tunnel,[1] the Staten Island Tunnel was also to be referred to by four other names:

- The Narrows Tunnel, after the Narrows, the body of water it was supposed to run under;[1]

- The Saint George Tunnel, after one of its terminals in St. George, Staten Island[1] (not to be confused with the tunnel between the terminal and the Tompkinsville station);[2]

- The Hylan Tunnel, after former New York City Mayor John Hylan, who oversaw the project.[1] It has also been referred to as Hylan's Holes in both derogatory and endearing contexts.[3]

Original plans

In 1888, subsequent to building the Arthur Kill swing bridge between New Jersey and northwestern Staten Island,[4] the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (the owners of the Staten Island Railway until 1971) proposed a tunnel between Staten Island and Brooklyn.[5] In 1890, Staten Island developer Erastus Wiman, who controlled the railway, sponsored a plan by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to construct a tunnel under the Narrows to connect Staten Island with Brooklyn for both passenger and freight service.[5][6][7] The proposal never made it through the approval process when financial challenges stopped the plan at the drawing board.[5] The tunnel would have gone from Vanderbilt Avenue at Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island to Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, traveling 1 1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) at a depth of 35 feet (11 m) below the narrows.[7] There would have been two lines of tunneling, parallel and close together.[7] Winman believed that the tunneling would cost $5,000,000 and that with the connecting road, the total cost was estimated at $6,000,000.[7]

A rapid transit route to connect Staten Island (alternately known as Richmond County) to the remainder of New York City was proposed in 1912, in conjunction with the Dual Contracts of the New York City Subway.[8][9] At the time, there were no vehicular or rail connections between Staten Island and the other four boroughs; the only connection was by ferry.[10] Although not funded by the city, the tunnel was expected to help expand the then-sparsely populated borough in a similar manner to the population and development explosions seen in Brooklyn and the Bronx.[1][10][11][12][13]

Under the Dual Contracts, three routes were proposed—two to Brooklyn and one to Manhattan—which would connect the Staten Island Railway's rapid transit service (SIRT) to existing subway lines.[6][8][13]

Manhattan route

The Manhattan proposal, often called the "direct route," would have connected with the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)'s lines under Battery Park, near the current Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel. "Direct Route A" would have utilized a five-section tunnel under the New York Harbor, while "Direct Route B" would have used a partially-elevated route running along the eastern coastline of New Jersey (near Greenville and Bayonne). Both Manhattan plans would have required connections to various points, including Ellis Island or Governors Island, and would have traveled around 5 miles (8.0 km) without any stops. Because of this, the high costs of the potential tunnel, and the relatively small population of Staten Island, the Manhattan route was considered impractical.[6][8][11][13][14][15] Another 5-mile tunnel to Battery Park was proposed by the city in the 1950s, but the plan was scrapped due to a lack of funding.[9]

Brooklyn routes

Both of the shorter, Brooklyn proposals would have connected to the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT)'s Fourth Avenue subway, constructed in 1914 during the Dual Contracts.[9]

The first route would have originated in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn at a point between 65th and 67th Streets (just south of 59th Street Station), running to Arrietta Street in Tompkinsville, Staten Island near the Tompkinsville Station and one stop away from the Saint George Terminal. This plan, referred to as "Route No. 51" under the Dual Contracts, would have had connections going north towards St. George and along the North Shore Branch towards Arlington, and south towards Tottenville on the Main Line and Wentworth Avenue along the South Beach Branch.[6][16][17][18][19][20] This proposal was estimated to cost $12,000,000 in the year 1912, with half of it to be paid by railroads, such as the Pennsylvania Railroad (which operated the Long Island Rail Road) and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (which operated the SIRT).[16][21][22] A major part of the 1912 proposal was the inclusion of two 40 inch water mains, which were to be side to side in an immense supply to be installed by the Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity alongside the tubes. These mains were intended to carry water from the main New York City supply to Staten Island.[16][21]

The second route would have originated in Fort Hamilton at the south end of the line. Similar to the 1890 proposal, it would have followed the routing of the current Verrazano–Narrows Bridge (constructed from 1959 to its opening in 1964). The Fort Hamilton proposal was the shortest route of the two, though it would require tunneling through deeper waters.[6][8][14][23] As part of the proposal, it was suggested that the Fourth Avenue Line be extended past its original terminal at 86th Street in Bay Ridge to a temporary ferry terminal at 95th Street (now the 95th Street Station).[6][23]

In anticipation of the northern tunnel route, trackways were constructed diverging from both Fourth Avenue local tracks towards the tunnel site south of the 59th Street Station.[6][18][20] An additional portal was built in the SIRT tunnel between Saint George Terminal and Tompkinsville to facilitate the northern wye from the tunnel to the North Shore branch.[2] As a provision for the southern route, the Fourth Avenue line south of 59th Street (built with only two tracks) was placed on the west side of Fourth Avenue, which would allow two additional tracks to be added on the east side of the street to facilitate a future express service from Staten Island.[23][24]

Groundbreaking and stoppage of construction

Selection of Bay Ridge-based plan

The Bay Ridge-based plan was ultimately selected, running between 65th Street/Shore Road in Brooklyn and the St. George Ferry Terminal in Staten Island. The two tubes would have been 10,400 feet (3,200 m) long, longer than any tunnel in the United States at that time.[11] Portions of the tunnel would be constructed using a tunnelling shield, while the remainder would be placed in a trench at the bottom of the Narrows.[25] In the final plans, each tunnel was designed to be 24 feet (7.3 m) wide to accommodate freight cars in addition to passenger service, with freight trains coming from the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s Bay Ridge Branch (terminating just north of the tunnel site) and the Staten Island Railway's connection with rail lines from New Jersey.[11][19][25]

Alternate plans included constructing two sets of two tubes, one for commuter and freight service from the LIRR and the other for rapid transit, or two tunnels each with individual tubes for freight and subway service.[11][19][25] The freight service would have occurred during off-peak hours only, but simultaneous with subway service, with passenger trains running in 30-minute or one-hour headways during these times. A 1912 proposal had freight running at night between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m., while the 1925 plans called for joint freight and passenger service during early mornings (5 a.m. to 6 a.m.), middays (10 a.m. to 4 p.m.), and overnights (8 p.m. to 5 a.m.).[2][11][16][25][26]

At the time of the tunnel's groundbreaking, Jamaica Bay and the Paerdegat Basin were slated to become industrial complexes, which would have been facilitated by freight service from the tunnel.[6][27][28] The tunnel plan was amended in 1919.[8] In April 1921, a bill was passed in the state senate requiring the city to begin construction of the 24-foot-wide (7.3 m) tunnel within two years.[11][29]

1922 plan

In May 1922, John Hylan launched a new plan for the freight and passenger tunnel, and the Board of Estimate recommended that $4,080,000 be initially appropriated for the project. The Transit Commission and the Port Authority refused to accept the plan, as they each had their own plans.[30] This plan was much less extensive than the original plan. The original plan would have had the tunnel from Owl's Head Park under the Narrows to Staten Island, and then continuing to a freight yard to be built in the center of Staten Island, from which a trunk line would run across the Arthur Kill to New Jersey as far as Paterson, before merging with the West Shore Railroad. The new revised plan would only cover the Narrows Tunnel, and a three-mile spur to Arlington Yard.[30]

Under the new plan, freight would still only operate at night through the tunnel. Spurs connecting the tunnel in Brooklyn to the Long Island freight belt line, to the B&O freight sidings on Staten Island, and to the new city piers on Staten Island would have all been built. The project was projected to cost $60,000,000 and if the job was done quickly, it could have been done by 1929.[30] The route would help develop the waterfront areas in Staten Island and Jamaica Bay. Provisions would be made for connections with the subway system's Fourth Avenue Line, even though the Transit Commission refused to be involved with the plans.[30]

Since the plan would benefit the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Pennsylvania Railroad opposed it, and the railroad, cooperating with the Port Authority, proposed a tunnel from Brooklyn to Greenville, New Jersey, with a spur to Staten Island.[30] The situation become complicated, as the Port Authority plan was approved by the State Legislatures in both New Jersey and New York. In addition, the Transit Commission proposed its own subway tunnel branching from the Fourth Avenue Line to be operated as part of the city's subway system.[30]

Groundbreaking and preparations

A groundbreaking ceremony was held by New York City Mayor John Hylan on April 14, 1923 in Bay Ridge[1][26][31] and in Staten Island on July 19.[6][32] Headings were dug and tunneling shafts were sunk at 68th Street and Shore Road in Brooklyn (the Shore Road Shaft), and underneath the Saint George Terminal in Staten Island (the South Street Shaft), costing a total of $1 million.[2][11][25][29] In addition, in preparation for the tunnel, the SIRT purchased one hundred ME-1 subway cars built to BMT specifications and electrified its three-passenger branches.[2][18][33] The impending completion of the tunnel also sparked real estate interests in Staten Island.[6][34]

Construction halted

In 1925, however—the year bids from contractors were to be entertained by the city—the project was halted and the project's engineering staff laid-off.[6] Officially, the plan was delayed due to lack of funding,[2][18] but Hylan and New York City Board of Transportation (BOT) Chairman John Delaney also wanted to secure freight service for the tunnel.[6][11] The status of the tunnel as mixed-use created tension and deadlock between Hylan, Delaney and the New York State Transit Commission; the latter emphasized passenger service for the tunnel.[6] After an investigation issued by Governor Al Smith, planners eliminated freight service from the plan, as per the Nicoll-Hofstadter Act signed into law by the governor; this then led to lack of interest from contractors.[1][6][11][31]

With the tunnel now designated exclusively for subway service, Mayor Hylan, a former Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) employee who was a known opponent of both the BMT and the IRT, supposedly stopped the project as part of an overall effort to cripple the two private subway companies and promote the plans for the city-operated Independent Subway System (IND).[3][9][18][35] It was also reported that Governor Smith, who had a financial stake in the Pennsylvania Railroad company, tried to stall the project in order to prevent the expansion of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad operations farther into the city.[2][18] The stoppage was also attributed to the political rivalry between Hylan and Smith, who were both members of Tammany Hall's Democratic Party.[6]

Nonetheless, on October 2, 1925,[36] the 95th Street subway station, which was built mainly in anticipation for the Staten Island Tunnel, was opened.[37] The station was built with a false wall at its south end, intended for either a planned extension to 100th or 101st Streets[38] or a line leading to a future Fort Hamilton-based tunnel.[23]

Completion proposals

The tunnel had gone only 150 feet (46 m) into the Narrows before it was halted; multiple proposals have resurfaced to complete the tunnel.[18][31][39] The tunnel and the Shore Road tunneling shafts currently lie dormant under Owl's Head Park in Bay Ridge.[1][6][9][31] The South Street Shaft in Staten Island was filled in 1946 during post-World War II renovations of Saint George Terminal.[1][13]

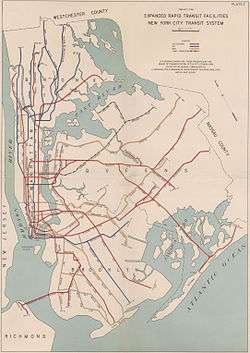

The IND Second System proposal from 1929 estimated that the cost of the southern tunnel route from Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island, to Fort Hamilton would cost upward of $75,000,000, though the tunnel was not officially part of the subway plans and was illustrated as a vehicular tunnel on the map of the plans.[6][10][40][41][42] Many of the proposals were part of this ambitious expansion plan, which would have connected the tunnel to the IND South Brooklyn Line (today's IND Culver Line).[9][12][29][43] An updated proposal in 1931 had the connection to the IND at the current Smith-Ninth Streets station, with the tunnel traveling north from Staten Island through Red Hook and Gowanus.[6][12][44] Yet another update, from 1933, was projected to cost $45,000,000, running the original route between Saint George and 67th Street in Bay Ridge. The line would then run on Second Avenue north through the Bay Ridge Flats on Brooklyn's western shore, meeting up with the Culver Line near Hamilton Avenue (the current Gowanus Expressway) between the Smith-Ninth Streets and Fourth Avenue stations;[45][46][47][48] it was suggested that the Hylan tunnel shafts be used.[46] An application for a $47 million loan for this extension was approved by the Board of Estimate in 1937.[6]

A revised Second System plan, drawn up in 1939 after the completion of the South Brooklyn line, followed the original Bay Ridge plan, and would have also extended the IND down Fort Hamilton Parkway and/or 10th Avenue to meet up with the tunnel route.[6][9][10][48][49] The IND connection would be located at either the Fort Hamilton Parkway station (where the express tracks of the line run on a separate level directly under the street)[10][50] or the Church Avenue express station, the former terminus of the line.[10] The Church Avenue connection would have utilized the lower level yard just south of the station, currently used to relay terminating G trains.[9] None of these plans were ever funded, due to the onset of the Great Depression and, subsequently, World War II.[6][9][10]

In 1945, the tunnel between New Brighton and the BMT Fourth Avenue Line in Brooklyn was submitted by the Board of Transportation to the City Planning Commission as part of the 1946 budget, this time costing $50,610,000.[51][52] Later in 1945, according to a report by Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia's special committee on transportation requirements of the Borough of Richmond, it was deemed that a tunnel to Staten Island from Manhattan was "unthinkable" and that a tunnel between Brooklyn and Staten Island was "not feasible now but must wait ten years". Robert Moses, who was the chairman of the committee and a known mass transit opponent, said that the best hope for improved transportation between Staten Island and Brooklyn and Manhattan was the reconstruction of the Saint George Terminal, the placing of more and better boats between Staten Island and Manhattan, resumption of 24-hour ferry service between 39th Street in Brooklyn and Staten Island, and the construction of ramps to the Gowanus elevated improvement at 39th Street.[53]

More recently, the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge, built from 1959 to 1964, had been proposed to serve as the rail link. The 95th Street station was slated to be connected to the bridge, one of the world's longest suspension bridges, because it followed the route of the planned tunnel. However, no space for any tracks was ever built because of Moses's opposition to the expansion of New York City public transportation.[6][9][18][23][39]

Modern proposals for completion of the tunnel have come from New York City Councilman Lewis A. Fidler, who has proposed a one-third of one percent tax for the tristate region to pay for the construction.[54] The tunnel was one of several projects that could have competed for $3 billion of federal funds that were to have been allocated to the ARC tunnel, which was canceled by New Jersey governor Chris Christie in October 2010. State Senator Diane Savino, whose district includes parts of Staten Island and Brooklyn, supported such a plan, saying, "The MTA should complete a 1912 plan that would have rail and freight access from the terminus of Victory Boulevard to Brooklyn, along 67th Street, then utilize the R train along Fourth Avenue." The plan's projected cost would be $3 billion, "the same as a proposed extension of the 7 line under the Hudson River."[55] Supporters stated that a rail tunnel would improve quality of life for Staten Islanders, reduce traffic, and increase the attractiveness of the borough for investment.[56]

Similar proposals

Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel

The nearby Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel is being planned to connect northeastern New Jersey and Long Island, with portals in Brooklyn and in Jersey City, New Jersey. The tunnel is being planned as a result of passenger and commuter traffic frequencies being at capacity and precluding freight movements.[57] As early as the 1920s, this tunnel had been planned to cross the entire New York Harbor rather than just the Narrows.[6][11][58] As a precursor to the planned project, which could cost up to $11 billion to build, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) compiled a Tier 1 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) in November 2014.[59]

Tunnels from Brooklyn to New Jersey via Staten Island

The former Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) also planned a railroad tunnel, for freight use, between Brooklyn and Staten Island in 1893. The PRR also proposed a tunnel from Brooklyn to Jersey City, approximately following the planned path of the Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel, ten years later. The project was never started, despite efforts by government planners to start the project from the 1920s through the 1940s.[60]

In January 1935, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia solicited the PANYNJ's help to create a report, called the "Summary of Cross Bays Freight Tunnel Study (Routes via Staten Island)," detailing four routes for a freight tunnel running to New Jersey via a tunnel to Staten Island. However, the only option that was deemed feasible was one that went from the end of the Bay Ridge Branch in Brooklyn to Greenville Yard in Greenville, New Jersey, which could either go through Staten Island or directly under the New York Bay. While the route via Staten Island, estimated at $35 million, could potentially accommodate a passenger line at a cost of another $28 million, other costs made the direct route cheaper.[60]

In 1978, Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade and Douglas studied four options for a tunnel from Brooklyn to New Jersey, some involving a tunnel to Staten Island. These included an option for a tunnel directly from Greenville Yard to the Bay Ridge Branch, and a link from New Jersey to Manhattan. Also under consideration was a single-tube tunnel with accommodations for electric units only. The Greenville–Brooklyn tunnel would be about $331 million, which was cheaper than the approximately $405 million tunnel from Staten Island to Brooklyn.[60][61]

Boulevard Subway plan

In 1912, Wood, Harmon & Co proposed a new subway from Bayonne, New Jersey, to Staten Island. This was called the Boulevard Subway. In their advertisements, the company stated, "Five or ten years from now—when the subway to Staten Island is built—… some Doubting Thomases of New Yorkers who don't buy will be shedding tears at their lack of foresight."[62]

The plan resurfaced in 1929, when meetings took place between Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague and officials from New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker's office. This plan proposed a subway line running along the SIRT North Shore Branch and John F. Kennedy Boulevard in New Jersey, before connecting with the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (today's PATH train) at Exchange Place. The service would have provided access to Lower Manhattan via the H&M's Downtown Hudson Tubes to Hudson Terminal (now the site of the World Trade Center station). There were also plans to extend the line to the George Washington Bridge in Fort Lee.[6]

See also

- Proposed expansion of the New York City Subway

- Rail freight transportation in New York City and Long Island

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Niebuhr, Robert E. (November 27, 1964). "They Called The 1923 Narrows Tunnel: 'Hope And A Hole In The Ground'". brooklynrail.net. Home Reporter and Sunset News, Brooklyn Historic Railway Association. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pitanza, Marc (2015). Staten Island Rapid Transit Images of Rail. Arcadia Pubishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2338-9.

- 1 2 Boys, Bowery. "KNOW YOUR MAYORS: JOHN F. HYLAN". The Bowery Boys: New York City History. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Matteo, Thomas (April 22, 2015). "B&O Railroad had strong presence on Staten Island for 100 years". Staten Island Advance. Staten Island, New York. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "From Transportation Asset to Barrier". College of Staten Island Library Website. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Joseph B. Raskin (1 November 2013). The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-5369-2. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "To Tunnel The Narrows And Thus Improve New York's Commercial Facilities: Mr. Erastus Winman's Latest Plan Upon Which He and Others Have Long Been Mediating". The New York Times. August 5, 1890. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "To Act This Year on the Richmond Tube: Route Approved in 1912 Still Alive-May Soon Be Adopted Anew or Amended". The New York Times. February 13, 1919. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "DC: A Tunnel from SI to Brooklyn?". Daniel Convissor. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Roger P. Roess; Gene Sansone (23 August 2012). The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-3-642-30484-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Young, James C. (May 10, 1925). "Staten Island Waits for Narrows Tunnel". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Transit Progress on Staten Island". The New York Times. April 19, 1931. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Subway that was Never Built". brooklynrail.net. Westerleigh Improvement Society. November 1981. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Maps Out Tunnel to Staten Island: Commissioner Delaney Now Has Engineers at Work on the Surveys and Plans". The New York Times. November 9, 1919. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Suggests Battery Tunnel: Staten Island Committee Offers Plan for Direct Route". The New York Times. March 25, 1919. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tubes Under Bay to Boom Brooklyn: Will Enable Great Trunk Lines to Deliver Freight to Water Front Here". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 16, 1912. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Subway Running To Eighty-Sixth Street Starts Building Boom In Bay Ridge". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 15, 1916. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Leigh, Irvin; Matus, Paul (January 2002). "Staten Island Rapid Transit: The Essential History". thethirdrail.net. The Third Rail Online. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel: Add Subway To Staten Island and More!" (PDF). Brooklyn Historic Railway Association. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Annual Report of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. for The Year Ending June 30, 1912" (PDF). bmt-lines.com. Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. June 30, 1912. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Subway Agreement Receives Approval Among Officials". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 15, 1912. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "MTA Capital Program 2015-2019" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 24, 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "To Extend Subway to Fort Hamilton". The New York Times. August 26, 1922. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Subway Extension Plan: Fourth Ave. Line to 86th St., Tunnel to Staten Island, and Eventually a Through Route to Coney Island". The New York Times. February 16, 1912. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The City of New York Board of Estimate and Apportionment: The Narrows Tunnel" (PDF). brooklynrail.net. New York City Board of Estimate, Brooklyn Historic Railway Association. 1925. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Staten Island Tube Started by Hylan". The New York Times. April 15, 1923. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Paerdegat Basin and the Jamaica Bay Project". The Weekly Nabe. April 4, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ "PUSHES PORT PLANS FOR JAMAICA BAY; Board of Estimate Committee Approves Buying Land for the Paerdegat Basin Railroad. FAVORS DREDGING PROJECT It Also Recommends Extension of Tracks of Long Island Road to Canarsie and Barren Island.". The New York Times. October 22, 1930. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 "City Rapid Transit Urged in Richmond". The New York Times. April 19, 1932. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "City Committed to Spend $4,000,000 on Narrows Tunnel; No Definite Settlement Made for Future Operation". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 7, 1922. p. 27. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Spencer, Luke J. "Staten Island's lost subway tunnel". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Hylan Swings Pick at Shaft Opening; Formally Starts Work at the Staten Island End of Narrows Tunnel". The New York Times. July 20, 1923. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ "Staten Island Is Not a Commuting Community". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 5, 1924. p. 67. Retrieved 26 April 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Center of a Nation's Government". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 12, 1925. Retrieved 19 July 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Delays Due to the Mayor: Board of Estimate Also Criticized in an Exhaustive Report". The New York Times. February 9, 1925. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "95th St. Subway Extension Opened At 2 P. M. Today". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 31, 1912. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Three Rapid Transit Contracts are Let". The New York Times. December 29, 1922. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Discuss Subway Work: Fort Hamilton Taxpayers Want 100th Street Extended". The New York Times. September 24, 1911. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- 1 2 Martin, Douglas (November 17, 1996). "Subway Planners' Lofty Ambitions Are Buried as Dead-End Curiosities". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Duffus, R.L. (September 22, 1929). "OUR GREAT SUBWAY NETWORK SPREADS WIDER; New Plans of Board of Transportation Involve the Building of More Than One Hundred Miles of Additional Rapid Transit Routes for New York". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "New Tubes Cost $200,000,000 But Pay For Selves: Huge Projects Financed So That Taxpayer Handles None Of The Burden". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 28, 1929. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Board of Transportation of the City of New York Engineering Department, Proposed Additional Rapid Transit Lines And Proposed Vehicular Tunnel, dated August 23, 1929

- ↑ "New Yorkers Urge Loan For Tunnel". The New York Times. Washington, D.C. September 22, 1932. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Suggested Rapid Transit Lines in Richmond Borough". historicrichmondtown.org. Historic Richmond Town. 1930. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "The New Plan for a Tunnel". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 18, 1933. Retrieved 19 July 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Tunnel Prospects Bright". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 19, 1933. Retrieved 29 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Richmond Tube Report by Board Due Next Week". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 8, 1933. Retrieved 19 July 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Bay Ridge Tube's Fate Rests with Meeting Today: Staten Island Tunnel O.K. May Be Reversed If M'Aneny Attends". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 29, 1933. Retrieved 19 July 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Project for Expanded Rapid Transit Facilities, New York City Transit System, dated July 5, 1939

- ↑ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Borough Park" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "City Rapid Transit Urged in Richmond". The New York Times. August 24, 1945. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ↑ Jaffe, Alfred (December 6, 1946). "Borough Subway Relief Still 2 or 3 Years Off". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. pp. 1, 5. Retrieved 9 October 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tunnel Plan Out For Staten Island: Mayor's Special Group Reports That Tubes to Manhattan are "Unthinkable"". The New York Times. November 17, 1945. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ↑ Kuntzman, Gersh (2007-11-10). "Fidler's folly: Let's tunnel to SI!". The Brooklyn Paper. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ↑ Randall, Judy L. (2010-11-20). "Savino calls for subway, rail links for Staten Island with floating $3B in federal funding". Staten Island Advance. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ↑ Schwartz, Sam (2010-10-14). "Staten Island needs N.J. tunnel money: The borough, plagued by traffic, deserves better transit". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ↑ Christopher T. Baer, Ed. (June 2004). "PRR Chronology" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society.

- ↑ "SAYS ROADS BLOCK PORT UNIFICATION; Van Buskirk Discusses Authority's Project Before Jersey City Kiwanians. EXPLAINS BELT LINE PLAN: Commissioner Indicates That No Particular Rall Line Can Long Prevent the Work". The New York Times. November 24, 1922.

- ↑ CHFP draft Tier 1 EIS

- 1 2 3 Gareth Mainwaring (2002). "The development of the New York Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project" (PDF). Hatch Mott Macdonald (Toronto, ON). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2005.

- ↑ Cross Bay Tunnel Alternatives; Intermodal Study; Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade & Douglas; April 1978.

- ↑ "The Planned Subway Lines That Never Got Built—And Why". Curbed NY. 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2015-09-22.

Coordinates: 40°38′26″N 74°02′08″W / 40.64061°N 74.035642°W