Far East Air Force (United States)

| Far East Air Force | |

|---|---|

|

A-27s of the 17th Pursuit Squadron at Nichols Field, November 1941. | |

| Active | 16 November 1941 – 5 February 1942 |

| Country | United States of America |

| Branch |

United States Army Air Forces Philippine Army Air Corps |

| Role | Air defense of the Commonwealth of the Philippines |

| Size |

C. 6,500 personnel C. 300 aircraft |

| Part of | United States Army Forces Far East |

| Garrison/HQ | Nielson Field, Luzon |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Lewis H. Brereton |

The Far East Air Force (FEAF) was the military aviation organization of the United States Army in the Philippines just prior to and at the beginning of World War II. Formed on 16 November 1941, FEAF was the predecessor of the Fifth Air Force of the United States Army Air Forces and the United States Air Force.

Initially the Far East Air Force also included aircraft and personnel of the Philippine Army Air Corps. Outnumbered operationally more than three-to-one by aircraft of the Japanese Navy and Army,[1] FEAF was largely destroyed during the Philippines Campaign of 1941–42. When 14 surviving B-17 Flying Fortresses and 143 personnel of the heavy bombardment force were withdrawn from Mindanao to Darwin, Australia in the third week of December 1941, Headquarters FEAF followed it within days. The B-17s were the only combat aircraft of the FEAF to escape capture or destruction.[2][3][nb 1]

FEAF, with only 16 Curtiss P-40s and 4 Seversky P-35 fighters remaining of its original combat force, was broken up as an air organization and moved by units into Bataan 24–25 December.[4] 49 of the original 165 pursuit pilots of FEAF's 24th Pursuit Group were also evacuated during the campaign, but of non-flying personnel, only one of 27 officers and 16 wounded enlisted men escaped the Philippines.[5] Nearly all ground and flying personnel were employed as infantry at some point during their time on Bataan, where most surrendered on 9 April 1942.[6]

The surviving personnel and a small number of aircraft received from the United States were re-organized in Australia in January 1942, and on 5 February 1942 redesignated as "5 Air Force". With most of its aircraft based in Java, the FEAF was nearly destroyed a second time trying to stem the tide of Japanese advances southward.

1912–1941

Army aviation in the Philippines

In August 1907, Brigadier General James Allen, the United States Army's Chief Signal Officer, established the Aeronautical Division as the nation's air service and oversaw the introduction of powered heavier-than-air flight as a military application. Four years later Allen recommended the establishment of an air station in the Philippines. Military aviation began there on 12 March 1912,[nb 2] when 1st Lt. Frank P. Lahm of the 7th Cavalry, detailed to the Division, opened the Philippine Air School on the polo field of Fort William McKinley, using a single Wright B airplane to train pilots.[7] Ultimately attriting four of the Army's first 18 airplanes, aviation went temporarily out of business when the last plane crashed into Corregidor's San Jose Bay on 12 January 1915.[8]

The first U.S. aviation unit stationed overseas was the 1st Company, 2nd Aero Squadron, sent to Corregidor in January 1916. It used four Martin S seaplanes to adjust battery fire for Fort Mills, but was demobilized at the end of World War I.[9][nb 3] A new 2d Aero Squadron returned in December 1919, and a permanent military aviation presence was established with the organization on 20 March 1920 of the 1st Observation Group of the United States Army's Air Service at Fort Stotsenburg, consisting of the 2nd Squadron on Corregidor and the 3rd Squadron at Fort Stotsenburg. An additional squadron, the 28th, was activated on 1 September 1922 at Nichols Field, and the group, now at Clark Field, was redesignated the 4th Composite Group on 2 December 1922. On 25 January 1923 the three squadrons, all equipped with the Boeing DH-4, were redesignated, respectively, the 2nd Observation, 3rd Pursuit, and 28th Bombardment Squadrons.[10]

The air forces in the Philippines were a component of the Army's Philippine Department, and like the Army Air Corps in the continental United States, operated under split authority. Their nominal head was the Air Officer, Philippine Department, a staff member who did not exercise command of any operational units. Actual command of the operational forces (the 4th Composite Group) resided with the group commander, who reported through the chief of staff to the commanding general of the Philippine Department, and also through the Air Officer to the Chief of the Air Corps. Installations and airfields were maintained by service forces assigned to the Philippine Department, over which neither officer had any authority.

Maintenance of a defensive status quo of the Philippine Department was mandated by provisions of the 1922 Conference on the Limitation of Armament, although air power was not specifically mentioned in its terms.[11] Between 1924 and 1931, when deliveries of new aircraft ceased because of the Great Depression, the department received first-line equipment including the Martin NBS-1 (1924-1930); Keystone LB-5 (1929-1931); and Keystone B-3A (1931-1937) bombers;[12] and the Boeing PW-9 (1926-1931) and Boeing P-12E (1930-1937) fighters.[13] The primary observation aircraft after the retirement of the DH-4 was the Thomas-Morse O-19 (1931-1937).[14] After 1931 the 4th Composite Group became a "dumping ground" for aircraft that had become obsolete or worn out, discarded by units in both the Continental United States and the Hawaiian Department.[15]

By September 1939 the aggressive threat of Japanese imperial ambitions to the Philippines was recognized by the United States, but the Army and Navy were at odds on a strategic stance for countering it. The Air Board[nb 4] determined in keeping with War Department policy that air defenses of the islands would not be strengthened by modernization or expansion, tacitly accepting that the Philippine Department was a "sacrifice force."[16] On 31 May 1940, Maj. Gen. George C. Grunert, a mustang officer who had entered the Army during the Spanish–American War, took command of the Philippine Department. From the first he was dissatisfied with the staffing, equipment, and level of training of the department, but in particular the air forces, and intensively lobbied the War Department for modernization and reinforcements.[nb 5] Of thirteen fields available for use throughout the islands, only Clark Field was considered a first rate facility, and the small number of total fields made dispersal during wartime impossible.[15][nb 6]

Grunert's air force in July 1940 consisted of 28 Boeing P-26A "Peashooter" fighters (out of 34 originally shipped to the Philippines in 1937), 17 Martin B-10 bombers, 10 Douglas O-46 observation planes (the newest planes in the department), five 1920s-vintage ZO-19E observation craft (the "Z" modifier indicated they were unfit for front-line duty and could only be used as trainers), and three fabric-covered biplanes used for liaison, transport, and courier duties. The group had only 26 of the 51 pilots authorized it by its table of organization and equipment.[15] In a limited response to Grunert's requests, on 5 August 1940 Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall approved the upgrading of Grunert's antiaircraft defenses,[17] followed by presidential authorization on 18 October for the personnel transfer of two fighter units, the 17th and 20th Pursuit Squadrons, to fly 52 Seversky P-35s to be diverted from a consignment embargoed from a sale to Sweden. These measures were considered by the War Department to be "one-shot operations" and not a shift in its defense policy for the Philippines.[18][nb 7]

The senior Air Corps officer in the Philippines was Col. Col. Harrison H. C. Richards,[nb 8] the Department Air Officer. Col. Lawrence S. Churchill, commanding the 4th Composite Group, was a year his junior in rank. Cooperation and approval by Richards, a West Pointer, was necessary to accomplish support tasks for the 4th Group, but many officers felt he withheld information from Churchill and deliberately sabotaged group operations. While both colonels were fifty-one years old in 1941, neither had the confidence of Grunert, possibly because of open animosity each displayed against the other. In March 1941, Grunert wrote Marshall requesting that a general officer be transferred to Manila to command the Department's air force.[19][nb 9]

Philippine Department Air Force

The Philippine Department Air Force was formed on 6 May 1941[20][21][nb 10] as the War Department hastily reversed course and attempted to upgrade its air defenses in the Philippines. The general officer requested by Grunert arrived on May 4 in the person of Brig. Gen. Henry B. Clagett, who had just completed a three-week air defense course taught at Mitchel Field, New York, to familiarize him with the concepts of integrating Signal Corps radars, radio communications, and interceptor forces.[nb 11] Marshall had also given Clagett a top-secret mission to go to China in mid-May for a month of observation and assessment of Japanese tactics.[22] The PDAF's only major unit, the 4th Composite Group, consisted of five squadrons based at two grass fields: Clark and Nichols. A third airfield, Nielson Field, lacked facilities and was used primarily as an administrative strip for nearby Fort McKinley. An isolated sod auxiliary strip at Iba on the west coast was used for gunnery training. PDAF's materiel was centrally located in the Philippine Air Depot at Nichols Field, easily targeted from the air and highly inflammable.[23] The only existing antiaircraft defenses were a single battery of four 3-inch gun M1903 guns and a searchlight platoon at Fort Wint at the entrance to Subic Bay, which would only be marginally reinforced in September.[24]

In May 1941 its aircraft situation was only marginally better than a year before: only 22 P-26 fighters,[25] 12 "utterly obsolete, ancient, vulnerable as pumpkins" B-10s,[26][27] the 56 P-35As diverted from the sale to Sweden,[28] 18 Douglas B-18 Bolos still in crates after disassembly and shipment from the Hawaiian Department in March,[28] nine North American A-27s impressed from a foreign sales consignment,[nb 12] several Douglas C-39 transports, and a small number of varied observation planes.[nb 13] Its only modern aircraft were 31 Curtiss P-40B fighters earmarked for the 20th Pursuit Squadron. Although delivered in mid-May, they were not operational for lack of antifreeze engine coolant.[28] PDAF Headquarters was located at Fort Santiago near Manila; the majority of the planes were at either Clark or Nichols.[29] Except for one small commercial firm in Manila,[nb 14] no oxygen-producing plants existed in the Philippines, severely limiting the service ceiling of all aircraft, but particularly the fighters.[30][nb 15]

Clagett immediately undertook an administrative "shakeup" of the existing organization. He marginalized Richards, relieved Churchill of command of the 4th Composite Group (but retained him in the position of base commander of Nichols Field), created new channels of command, and because of a lack of qualified staff officers, drew senior (but administratively untrained) officers from the squadrons to fill his staff. The last move further aggravated a problem created when experienced pilots of both the 17th and 20th squadrons had been transferred to augment the understrength 4th Group. A lack of cohesion and confidence in command resulted that continued into the war.[31][nb 16] Richards and Churchill both responded with "obstructionist tactics" that exacerbated the already poor command situation.[32]

In July, the P-40s finally became operational, but Nichols Field was then closed to replace its east-west runway with one made of concrete, and to regrade the north-south runway, both measures taken to correct drainage deficiencies that made the field virtually inoperable in the wet season May through October. On the morning of 2 July (ironically, delayed five days by a typhoon),[33][nb 17] all three fighter squadrons transferred the FEAF's 39 P-35s and 20 P-26s to Clark and Iba, where the 17th Pursuit Squadron moved for gunnery training.[34] Construction of two new fields intended to support heavy bomber operations, at Rosales on the Lingayen Plain and Del Carmen near Clark Field, proceeded slowly.[35]

On 26 July 1941, Gen. Douglas MacArthur was recalled to active duty from retirement and the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) was created by the War Department to reorganize the defenses of the Philippines against a Japanese invasion. The PDAF was renamed Air Force, USAFFE on 4 August 1941,[21][36] and incorporated into its ranks the newly inducted Philippine Army Air Corps on 15 August 1941.[37] Its headquarters moved to Nielson Field, and although the move had been made to increase the urgency of expanding air capabilities, precious time had been lost that was never re-gained.[38]

Creation of the FEAF

Pre-war upgrades and expansion

In July 1941, Chief of the Army Air Forces, Major General Henry H. Arnold, allocated 340 heavy bombers (not yet manufactured) and 260 modern fighter planes for future reinforcement of the Far East Air Force.[39] Work at Nichols continued slowly in the second half of the year, but the 17th PS was forced to return there to accommodate the planned arrival of the heavy bombers, and the accident rate, already high, increased.[40]

By 1 October, 50 P-40Es had also been shipped to the islands,[41][nb 18] and a new organization, the 24th Pursuit Group, stood up to control the three pursuit squadrons.[42][nb 19] Between 10 February and 20 November 1941 FEAF received 197 additional pilots, 141 of whom were or became pursuit pilots.[nb 20] All except 28 of the fighter pilots were fresh from flight schools and required further individual training, which cut into needed unit tactical training.[43][nb 21] Arrangements were made with the oxygen-producing plant in Manila, which supplied the U.S. Navy's shipyard at Cavite, to buy any surplus for pursuit units, but output was so small that only the squadron at Nichols (which reopened on 17 October) could be supplied, and on a limited basis.[30]

The 14th Bombardment Squadron, assigned the best crews and nine B-17s of the 11th Bomb Group in Hawaii, was detached from that group to pioneer an air ferry route to the Philippines, arriving 12 September in the middle of a typhoon. Two squadrons of the 19th Bombardment Group followed in October–November. The 14th and 28th Bomb Squadrons[nb 22] were attached to the 19th BG and a total of 35 B-17 Flying Fortresses constituted the FEAF's heavy bombardment force.[44][nb 23]

Arnold wrote on 1 December 1941, "We must get every B-17 to the Philippines as soon as possible."[45] The War Department projected 165 heavy bombers and 240 fighters to be based in the Philippines by March 1942.[46] B-17s of the 7th Bombardment Group based in Utah staged in California and its 88th Reconnaissance Squadron was in-transit by air at the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.[47]

The personnel of two squadrons of the 35th Pursuit Group (the 21st and 34th, their pilot rosters at half strength), and three of the 27th Bombardment Group (Light), moved by a convoy of two transports escorted by the cruiser Louisville, but without their airplanes, and disembarked at Manila on 20 November 1941. The pursuit squadrons were attached to the 24th Pursuit Group and acquired P-35s from the other squadrons for training purposes. A shipment of 24 crated P-40Es arrived in Manila by freighter on 25 November, the first of 50 intended for the 35th Pursuit Group, and were trucked to the Philippine Air Depot at Nichols Field for assembly.[48][49][nb 24]

From a force of five squadrons (one bombardment, one observation and three pursuit) and 110 operational aircraft in May 1941, the Philippine Department now had thirteen squadrons and 195 combat aircraft. However, only ten squadrons had airplanes (four bombardment, five pursuit, and one observation), and although most of its new equipment was considered first-line by the Army Air Forces, none of it was first-rate by the standards of air forces already engaged in aerial combat. Further, the overwhelming majority of its fighter pilots were sorely lacking in meaningful flying experience.[50][51][nb 25]

FEAF organized

MacArthur held the position that Japan would not attempt an invasion of the Philippines before April 1942. Clagett (described by one historian of the campaign as lacking "the necessary elasticity of mind and body for realistic preparation for total war")[52] had twice been hospitalized during mid-1941 and was not meeting the demands of even this scenario. At the beginning of September Arnold met with Marshall to identify a replacement for Clagett who would infuse the necessary urgency into the Philippine buildup.[53]

Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton arrived in the Philippines to command FEAF on 4 November 1941.[nb 26] Bomber, fighter, and service commands for the FEAF were organized when it stood up on 16 November 1941; Clagett was placed in command of the provisional 5th Interceptor Command and Churchill made commander of Far East Air Service Command.[nb 27] When a war warning from Marshall was received in the Philippines on 28 November (Philippine time), FEAF began dispatching two B-17s daily on reconnaissance flights of the sea lanes north of Luzon, but with orders not to overfly Japanese territory on Formosa. Units worked to complete protective and dispersal measures, while interceptors were armed and placed on alert status.[54]

The arrival of National Guard units at the end of September provided the first ground defenses for Clark Field. Two battalions of light tanks were positioned at Fort Stotsenburg in late November to protect Clark against seizure by Japanese airborne troops, while the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment (AA) provided limited antiaircraft artillery defense with .50-caliber machine guns and a dozen 3-inch guns.

The "Pensacola convoy" of seven transport vessels gathered at Honolulu and sailed for Manila on 29 November, transporting the 52 Douglas A-24 dive bombers of the 27th BG, 18 P-40s intended for the 49th Pursuit Group, 48 pilots of the 35th PG, 39 recent flight school graduates on "casual" status, and the ground echelons of five squadrons,[55] all escorted by the USS Pensacola. The remainder of the 35th Group (the remaining pilots, two pursuit squadrons, and group headquarters) sailed aboard the USAT President Garfield for Honolulu on 6 December to join another convoy.

Aircraft inventory on 8 December 1941

Each of the five pursuit squadrons had a TO&E strength of 25 aircraft including spares, but because of accidents and other factors, none had that total.[nb 28] The decision was made by FEAF to use only 18 in tactical commission, regardless of the number in their inventory. 20 P-40Es had been delivered to the 21st PS on 4 and 6 December but many had not yet had their engines slow-timed and none had more than two hours of flying time.[56] All of the P-35As had been over-used for gunnery training because of a shortage of .50-caliber ammunition and needed engine changes (none were operationally available and the Far East Air Depot had neither facilities nor personnel for large-scale engine maintenance), while their guns were wholly unreliable from poor maintenance.[57][nb 29] The ammunition shortage also resulted in practically none of those equipping the P-40s being test-fired, much less used in gunnery practice, and many failed in combat.

FEAF had only 54 fully operational and capable P-40s and 34 B-17s on 8 December.[1] Against these 88 fighters and bombers, the Japanese committed 288 first-line combat aircraft in fully trained units of the Navy's 11th Kōkūkantai and Army's 5th Hikōshidan to support its Luzon operations: 108 land-based naval bombers, 54 army bombers,[nb 30] 90 Mitsubishi A6M Zero carrier fighters, and 36 Nakajima Ki-27 (Army Type 97) "Nate" army fighters.[58][nb 31]

The numbers below in italicized brackets indicate the number of FEAF aircraft in the inventory actually flyable on 8 December.[59][60] If no figure is listed, the number of usable aircraft is unknown.

- Boeing B-17C/D: 35 (32) [nb 32]

- Curtiss P-40B/E: 91 (89) [nb 33]

- North American A-27: 8 (1) [nb 34]

- Seversky P-35A: (26) [nb 35]

- Douglas B-18A: 18 (15, all as trainer-transports, with 2 at Del Monte)

- Martin B-10B: 3 (1 PAAC)

- Boeing P-26A: 12 (12 PAAC)

- Curtiss O-52: 11

- Other: 46

There were 60 additional aircraft in the Philippine Army Air Corps, including one Keystone ZB-3A bomber. 42 were Stearman 76DC trainers of varying serviceability and utility.

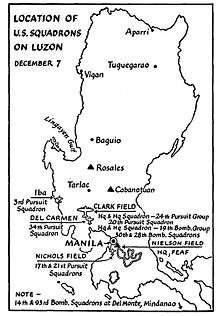

FEAF airfields

Within 80 mi (130 km) of Manila, the Army had six airfields (Clark, Nichols, Nielson, Iba, Del Carmen, and Rosales), two of which were auxiliary strips nearing completion. Another four auxiliary strips were begun in November: O'Donnell and San Fernando near Clark, San Marcelino northwest of Subic Bay, and Ternate west of Cavite (Ternate and San Fernando were never finished).[61][62] No strips were planned on Bataan, despite its prominence in strategic war planning. In August and October 1941, the War Department allocated US$9,273,000 (approximately $150 million in 2015 dollars) to construct and improve airfields, most of which was spent constructing a concrete runway at Nichols Field (the only hard-surfaced runway in the Philippines).[63] Additional graded strips were also added or extended to the grass runways at Clark Field, with the rest of the allocated funds used to build the auxiliary fields.[64] The auxiliary strips were dirt-surfaced and without maintenance, servicing, communications, or control facilities. The dust clouds generated by takeoffs at all strips except Nichols seriously hampered flight operations, with numerous mishaps that destroyed many aircraft, killed pilots, and reduced the assigned strength of already tiny combat missions.[65] The use of expedients to cut down the dust, including a molasses mixture deposited by a tank truck, was unsuccessful.[66][67]

Del Monte Field was operated by FEAF on the island of Mindanao. In November 1941, with the B-17s of the 7th Bomb Group expected to arrive in December, Clark Field was still the only base that could support heavy bombers but its all-grass parking areas and taxi strips could not withstand heavy operations when wet, making dispersal nearly impossible.[68] Informed that three more groups were projected to arrive in January and February, MacArthur and his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, favored new bomber bases in the Visayas but recognized that selected sites at Cebu and Tacloban would not support bomber operations without significant and expensive construction of runways. As a compromise, on 24 November 1941 the newly arrived 5th Air Base Group was hurried 800 mi (1,300 km) south to northern Mindanao by inter-island steamer to build a second bomber base for the 7th BG. Begun 27 November on the site of an emergency landing strip surveyed in September 1941, the new base was situated next to the Sayre National Highway 1.5 mi (2.4 km) northwest of Tankulan in Bukidnon Province.

Established in a "natural meadow" on a high plateau 21 mi (34 km) southeast of Cagayan City, and flanked on both sides by low hills, the site was in a pineapple plantation owned by the Del Monte Corporation. It needed only the cutting of grass to create a hard, all-weather sod runway. Del Monte No. 1, the bomber runway, was ready for limited operations by 5 December. A much smaller pre-war liaison strip, situated across the highway to the southwest on a small golf course,[nb 36] was designated Del Monte No. 3, and a parallel runway for fighter operations later cut northeast of the bomber runway was called Del Monte No. 2.[69]

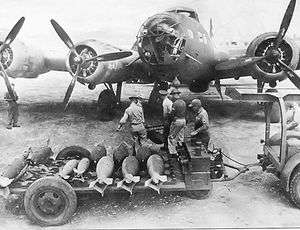

After Japanese intruder and weather reconnaissance flights were detected on several successive nights, sixteen B-17s of the 14th and 93d Bombardment Squadrons were dispersed from Clark to Del Monte No. 1 on the night of 5–6 December, circling until dawn (5 December in the United States) before landing. They intended to remain only 72 hours because neither maintenance facilities nor barracks had yet been built, and only a single radio was operating. Two understrength ordnance companies from Clark had preceded them to Del Monte on 3 December and constructed their own camp in Tankulan, but the remainder of their personnel and all the materiel required, particularly aviation gas, did not depart Luzon until 10 December.[70] For several months after hostilities began, work continued on another Del Monte strip in the barrio of Dalirig, 4 mi (6.4 km) east of the bomber strip,[nb 37] and at crude but well-camouflaged dispersal fields located 25 mi (40 km) to 40 mi (64 km) further inland at Malaybalay, Valencia and Maramag in Bukidnon Province.

Lubao Field on Luzon, in the barrio of Prado in Pampanga Province, became the location for a new airfield after Clark and Nichols were neutralized by the Japanese. Begun in sugarcane fields along Highway 7 near the entrance to Bataan by 400 Filipino laborers under the supervision of Philippine Army engineers, the 3,600 ft (1,100 m) fighter strip was still not completed when most of the 21st Pursuit Squadron commanded by 1st Lt. William E. Dyess arrived from Manila on 15 December. Working around the clock, the combined force completed construction of the runway, constructed revetments and graded taxiways in preparation for basing a dozen P-40s and five P-35s there, flown by a mixed assortment of experienced pilots from all five pursuit squadrons.[71] Lubao Airfield began operations on 26 December and was superbly camouflaged. The 21st PS flew reconnaissance and other missions from Lubao until 2 January 1942, when the field was evacuated. On 29 December, three pursuits (two P-40s and a P-35) were salvaged at the last minute at Clark Field in the face of advancing Japanese units by a volunteer group of mechanics and flown to Lubao, where they were evacuated with the others.[72]

Five fighter strips were opened on Bataan to support defensive operations during the withdrawal and subsequent siege:

- Orani Field. A camouflaged dirt strip on the upper end of Bataan also opened operations on 26 December. The 34th PS received its transfer orders on Christmas Day and conducted twice daily reconnaissance flights using five P-40s. The 2,800 ft (850 m) field was camouflaged using rice straw and movable haystacks, and was not attacked before it too was abandoned, on 4 January.[73]

- Pilar Field. Aircraft withdrawing from both Lubao and Orani were flown to an airfield near Pilar which had been graded in rice fields by Filipino hand labor. Revetments had been built and camouflaged in one day on 26 December by the 17th PS. Operations at Pilar began on 1 January using the final three new P-40Es of the 25 November shipment, which were assembled in the last week of December at the Philippine Air Depot, relocated to Quezon City. The last mission from Pilar was flown 8 January, after which its nine P-40 aircraft displaced to Del Monte Field, Mindanao (only six arrived).[74]

- Bataan Field. The primary fighter base after the withdrawal into Bataan was originally graded in early 1941 as a 2,000 ft (610 m) dirt strip running uphill from a coastal road. Dubbed "Richards' Folly" after the Department Air Officer who had ordered its construction,[30] it was located on the Manila Bay side of Bataan about three miles north of Cabcaben, a village on the southern tip of the peninsula. The runway was widened and lengthened to 5,100 ft (1,600 m) after 24 December by the 803rd Aviation Engineers in anticipation of future operations. The first aircraft, two P-35s and an A-27 displaced from Lubao, arrived on 2 January, and on 4 January the nine P-40s at Orani were sent down.[75] Combat operations began on 8 January, the aircraft concealed in hidden revetments until they could be launched between raids made by Japanese dive bombers. The P-35s were flown to Mindanao on 11 January after the A-27 was lost in a landing accident.[76] Maintenance and operation of the field was assigned to the 16th Bombardment Squadron (27th Bomb Group), which had no aircraft, and damage to the runways from raids was repaired by Company C, 803rd Aviation Engineers.[77]

- Cabcaben Field. At the end of January 1942 a strip 3,900 ft (1,200 m) in length was hastily graded by civilian contractors 2.5 mi (4.0 km) south of Bataan Field and made operational as a dispersal field on 6 February. The 21st PS was recalled from infantry duties on 12 February to operate and maintain both it and Bataan airfields.

- Mariveles Field. The existing dirt liaison field at the southernmost point on Bataan was abandoned on 7 January, but at the end of the month a road adjacent to the field was extended and widened to provide a new fighter strip 65 ft (20 m) in width and 3,800 ft (1,200 m) long. Its orientation to the overlooking heights was such that once a pilot was committed to landing, he had no choice but to continue, and was subject to severe tail-winds. The 20th Pursuit Squadron was also recalled on 12 February to complete defensive position preparations, camouflage revetments, and maintain the field, which became operational on 23 February.[78]

Warning systems

The "Warning Service" of the Philippine Department was directed by Lt. Col. Alexander H. Campbell, who had originally transferred to the Philippines in October 1939 to command a battalion of the 60th Coast Artillery (AA). Functioning as an office of the Intelligence Section (G-2) of the department headquarters, the Warning Service operated an interim "Information and Operation Center" at Nielson Field that included an electrically lighted map to plot sightings that indicated origins of reports with twinkling lights. In lieu of working detection equipment and trained personnel, the Warning Service maintained a primitive system of 509 observation posts manned by 860 civilian watchers, unschooled in aircraft identification, who would report airplane movements by five radio, two telegraph, and ten telephone networks manned by members of all three U.S. military services, the Philippine Army and constabulary, the Philippine postal system, and civilian companies in the provinces. Interpreters were required for the many dialects used by the observers.[79] Message processing encountered significant delays between the time of observation and time of report.[31][nb 38]

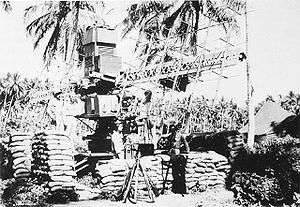

On 4 May 1941, the Warning Service was shifted to the new PDAF as the "Air Warning Service".[80] A newly trained 194-man Signal Corps air warning company arrived by transport on 1 August to operate two SCR-271C fixed-location air tracking radars planned for deployment on Luzon, each with a range of 150 mi (240 km).[81] Campbell immediately prepared a study for Clagett recommending 24-hour operations and modern aircraft detection equipment, specifically two mobile SCR-270B units and nine SCR-271s,[nb 39] allotting eight units to Luzon and three to Mindanao, and expanding the force to a 915-man battalion. He also suggested that radars be established at some future time on the islands of Lubang, Samar, Palawan, Jolo, Basilan, Tablas, Panay, and Negros.[82]

His specific recommendation was in line with the one SCR-270/seven SCR-271 recommendation of the Air Defense Board just received by the War Department, and was endorsed by MacArthur on 8 September with a recommendation for funds. MacArthur was notified by wire the next day that an SCR-270 and two SCR-271s were already in transit to the Philippines by ship for use by the air warning company, with three more SCR-270s to follow in October.[82] However, by 15 November, when the AWS was integrated into the new 5th Interceptor Command, plans for the fixed-location radar sites were only five percent complete and no date to begin construction had been set.[83] The 557th Air Warning Battalion was designated to provide the expanded early warning defense, and was at its port of embarkation at San Francisco on 6 December.[46]

The AWS received seven SCR-270 mobile units but only two were operating on 8 December: one in full operation at Iba, and a Marine Corps unit training at Nusugbu in Batangas Province. The latter was assigned to the Air Warning Detachment of the 1st Separate Marine Battalion in late November to provide protection to the Navy base.[84] The Iba unit had been operational since 18 October and was fully functioning. On 29 November, in response to the war warning sent to all overseas commands by Marshall, the detachment went on continuous watch in three shifts.[85]

Three Army detachments with mobile units and the Marine detachment were ordered into the field on 3 December with instructions to be in operation by 10 December. Of the Army detachments, at the onset of hostilities one had just reached position at Burgos, Ilocos Norte, in northwest Luzon; another was at Tagaytay, Cavite, with a damaged set; and the third was newly established at Paracale, Camarines Norte, in southeastern Luzon, where it had just completed calibration tests.[86][nb 40] The two fixed-location SCR-271s were in storage.[87]

USAFFE also received 11 sets of SCR-268 antiaircraft radars, a searchlight-control radar that could also be used for gun laying of AA weapons.[86][nb 41] After the FEAF was forced to withdraw into Bataan to continue operations, its primitive fields were subject to frequent attack from Luzon-based aircraft of the Japanese Army. An SCR-268 of the 200th Coast Artillery was placed in operation on the hillside above Cabcaben Airfield. Used in conjunction with the sole surviving SCR-270B unit,[nb 42] hidden in the jungle a mile from Bataan Field, it served as an early warning system and was linked to headquarters of the 5th Interceptor Command at Mariveles. Takeoffs and landings by the Bataan Field Flying Detachment required towing of P-40s off the runways to and from hidden revetments, and were vulnerable to strafing. The ad hoc system facilitated coordination of field operations, and while imperfect, no aircraft were lost during takeoffs or landings.[88]

Combat operations

Philippines campaign

Surprise attack

Japanese air operations against FEAF airfields on Luzon were scheduled to take off from their Formosan bases beginning at 1:30 am on 8 December, with attacks to commence 21 minutes after dawn (and approximately four hours after offensive operations began in Hawaii), at 6:30 am. However, reconnaissance flights dispatched to check weather conditions between Formosa and Luzon neither returned nor reported as launch time approached, and a thick fog over southern Formosa set back the timetable by 90 minutes. The commanders of Japanese units were disturbed when monitoring of American radio traffic indicated that the weather flights had been detected despite the darkness and attempts were made by Iba-based P-40s to intercept. Although all the interceptions failed, Iba Field was then substituted as a target in place of Nichols (where it was assumed that two squadrons of B-17s had dispersed) to deal with the new interceptor threat.[89] Further radio monitoring revealed to the Japanese that the U.S. Asiatic Fleet had been alerted at 4:00 am of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and they expected attacks on their own bases by B-17s (bombing through the fog undercast) at any time after 7:00 am. The air defense weaknesses of the FEAF were mirrored by those of the Japanese, who had prepared only for offensive operations, but no attack came before a final revised plan was issued at 7:50 am, ordering the main attack force of Japanese land-based aircraft to launch at 9:15 am and attack at 12:30 pm[90]

Brereton attempted in person to obtain authorization for attacks on Formosa soon after word of events in Hawaii reached Manila, but was twice prevented from speaking with MacArthur by Sutherland. The authorization was refused, apparently a misinterpretation of standing orders not to make "the first overt act."[nb 43] The P-40 squadrons at Clark, Iba, and Nichols moved to alert takeoff positions at 6:00 am as news of war spread among the units.[91] A large force of aircraft was detected flying south towards Luzon,[nb 44] prompting the takeoff at 8:30 am of 15 of the 19 B-17s at Clark with orders to patrol within communications range of its control tower, while the 24th Pursuit Group launched its three P-40 squadrons and the P-35 squadron at Del Carmen to patrol central Luzon for intruders. At 8:50 am and 10:00 am, telephone attempts to obtain authorization from USAFFE headquarters for a B-17 attack was also rebuffed by Sutherland. However MacArthur himself called Brereton at 10:15 am and released the bomber force to employ at his discretion. Brereton immediately ordered two bombers to conduct reconnaissance flights and recalled the rest to prepare for a late afternoon bombing mission. The B-17s and the fighters, which were low on fuel, all landed by 11:00 am to refuel and prepare for afternoon operations.[nb 45]

Japanese naval bombers and fighters took off according to their revised schedule and approached Luzon in two well-separated forces, both of which were detected by the Iba radar detachment just before 11:30 am. Despite an hour's warning, only the P-40 squadron at Iba took off, and it ran low on fuel in futile response to confusing instructions from the 24th PG that resulted from changing analyses of Japanese intents. The Iba P-40s were in their landing pattern when the Japanese struck. The aircraft at Clark and Iba were caught on the ground when the attack began at 12:35 pm. One hundred and seven two-engined bombers[92][nb 46] divided into two equal forces bombed the airfields first, after which 90 Zero fighters conducted strafing attacks until 1:25 pm (the fighters strafing Iba concluded at 1:05 pm, after which they flew to Clark and resumed attacks). Nearly the entire B-17 force at Clark, one-third of the U.S. fighters and its only operational radar unit were destroyed.[93][nb 47] The Japanese lost only seven fighters and a single bomber to combat.[94][nb 48]

Follow-up attacks on Nichols and Del Carmen fields, which were not targeted on 8 December, followed two days later, completing the destruction of AAF offensive and defensive opposition to the Japanese in the Pacific.[nb 49] A decision was made late that day to save the surviving fighters for reconnaissance use by avoiding direct combat.[95] Fourteen surviving B-17s, after just two days of small and unsuccessful attacks on Japanese amphibious forces,[nb 50] were transferred to Batchelor Field, Australia, for maintenance between 17 and 20 December, bringing Clagett with them. They resumed bombing missions from Australia against Japanese shipping in the Philippines, landing at Del Monte, beginning December 22 and continuing through 25 December. On January 1, 1942, the remaining ten operational bombers forward located to Java.[96]

Brereton evacuated FEAF headquarters on 24 December to Darwin, Northern Territory by way of the Netherlands East Indies, leaving the new head of the 5th Interceptor Command, Col. Harold H. George (promoted to brigadier general 25 January 1942) in command of units in the Philippines.[nb 51] Reduced to a single squadron-sized composite force, his pursuit fighters were carefully husbanded for reconnaissance duties and forbidden to engage in combat until forced to evacuate to fields hurriedly built on the Bataan peninsula, to which USAFFE and FEAF were ordered to withdraw on 24 December,[97] the last aircraft arriving on 2 January 1942.[98][nb 52]

Defense of Bataan

Combat and accidents reduced but did not eliminate the P-40 complement, and a group of pursuit pilots, called the "Bataan Field Flying Detachment," continued to fly missions until the last day of the campaign, employing mainly 30-pound fragmentation bombs and machine gun fire as ordnance.[99] Four of the six P-40s sent to Del Monte on 8 January were recalled to Bataan two weeks later, but only three arrived,[nb 53] leaving the detachment still with just seven P-40Es and two P-40Bs.[100][nb 54] The small detachment, gradually attrited, had a few notable successes:

- 26 January 1942, morning missions strafed boats attempting to reinforce Japanese landings behind the USAFFE lines on the west coast of Bataan, and shot down three Mitsubishi Ki-30 (Army Type 97) "Ann" dive bombers trying to support the landings. That night the detachment conducted a successful attack on Japanese aircraft at Nielson Field, then shot up a truck convoy on the north shore of Manila Bay.[101]

- 1–2 February 1942, a night attack by four P-40s flying two sorties each bombed and strafed a 13-barge convoy attempting to delivery 700 reinforcements to the Japanese beachheads, destroying nine and killing approximately half the troops aboard, confirmed later by Japanese records.[102]

- 2 March 1942, an all-day attack on shipping in Subic Bay and supply dumps on Grande Island resulted in 12 sorties. Claims included total destruction of an ammunition ship, but Japanese records could not be located to corroborate more than a subchaser sunk. However apparently extensive damage to at least four large ships was made. Four of the five remaining P-40s were used in the attacks, with one shot down and its pilot killed, and two others destroyed in landing accidents at Mariveles.[103]

A single flyable P-40E remained at Bataan Field, although by 5 March mechanics had repaired the damaged P-40B at Cabcaben using P-40E parts, facetiously calling the composite a "P-40 something".[104] Occasional individual reconnaissance flights were made in the following month by the two craft.[105][nb 55] Brig. Gen. George was evacuated by PT boat on 11 March, ending the effective usefulness of the detachment, whose pilots were severely debilitated by starvation and disease.[106] Churchill eventually succeeded to nominal command 12 days before the surrender, but was unable to evacuate and became a prisoner of war.[107]

Accidents put all three P-40s based on Mindanao out of commission by 9 February, leaving just two P-35s that had escaped from Bataan. Transfer of a propeller put a P-40 back in commission two days later, and shipment to Cebu by submarine of parts taken from wrecks on Bataan put another back in operation by mid-March, when a fire destroyed one of them on the ground. Three new P-40Es, still in crates, were shipped from Brisbane, Australia, by blockade runner on 22 February but ran aground on 9 March on a reef between Bohol and Leyte. Carefully hidden and moved by barge at night, the crates reached Mindanao on 26 March, where a makeshift air depot had been established in a coconut grove at Buenavista Airfield using mechanics of the 19th Bomb Group and the 440th Ordnance Company. By 2 April, all three P-40s were assembled and flight-tested, making the Mindanao P-40 force twice as large as that on Bataan.

The two P-40s on Bataan both flew out on 8 April, the P-40E to Iloilo City on Panay, where it landed wheels up, and the P-40B to Cebu. The two P-35s on Mindanao flew back to Bataan Field on 4 April and evacuated three pursuit pilots in their baggage compartments. A Navy Grumman J2F Duck that the 20th Pursuit Squadron raised from Mariveles Bay and placed in service again on 24 March evacuated five officers.[108][nb 56] Bataan surrendered the next morning. The P-40B reached Mindanao but crashed on 14 April trying to land at Dalirig in a heavy rain.

Although FEAF no longer existed as a command, its P-40s and service troops on Mindanao supported the final offensive air operations of the campaign. Early on 11 April ten B-25 Mitchell medium bombers of the 3rd Bomb Group and three B-17Es of the 40th Reconnaissance Squadron took off from Batchelor Field and arrived that evening at Del Monte. The small task force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ralph Royce, had originally planned to break the Japanese blockade of Luzon long enough for supplies to be delivered by sea to Bataan. However its surrender obviated that mission and instead the aircraft flew up for two days of attacks against the landing forces at Cebu City and Davao on 12 and 13 April.[109][nb 57]

The three new P-40Es and the sole remaining P-35 operated out of Maramag Field until 3 May. The P-35 was transferred to the Philippine Army Air Corps and two surviving P-40Es were ultimately captured intact by the Japanese army on 12 May.

Against the loss from all causes of 108 P-40s and 25 P-35s (25 in air-to-air combat), FEAF pilots were credited by USAF Historical Study No. 85, USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II, with 35 aerial victories between 8 December 1941 and 12 April 1942.[110][nb 58] 33 pursuit pilots were killed in the campaign and 83 surrendered to become prisoners of war,[5] with 49 of those dying in captivity.[111] 95% of enlisted men became POWs, and 61% of those died before they could be repatriated.[112][nb 59]

Netherlands East Indies campaign

Rebuilding the FEAF

On 29 December 1941, Brereton and his staff arrived in Darwin and reestablished FEAF headquarters. His only combat forces were 14 B-17s of the 19th Bomb Group sent south from Del Monte. By 1 January 1942, ten of the bombers had been shifted northwest to Singosari Airfield on Java,[113] from which the 19th BG flew its next combat mission on 4 January against Japanese shipping off Davao City, using Samarinda Airfield on Borneo as a staging base.[114] On 11 January the first aircraft of the 7th Bomb Group arrived via India and from that date on FEAF conducted its operations solely for the defense of the Netherlands East Indies.[115] FEAF became a part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDA) created to unify forces in the defense of the NEI.[116] On 18 January, FEAF headquarters moved to Bandoeng.[117]

The Pensacola convoy for the Philippines was diverted on 13 December to Brisbane, where it disembarked its Air Corps personnel and the crated A-24 dive bombers on 23 December, then continued to Darwin with field artillery reinforcements on 29 December.[118] The pursuit and partially trained pilots began training as assembly of the crated aircraft went forward at Archerfield and Amberley airdromes.[119] 21 pilots of the 27th Bomb Group[120] and 17 from the 24th Pursuit Group were flown to Australia in the last two weeks of December to ferry back the assembled aircraft,[121] but no engine coolant had been sent with the fighters[nb 60] and the guns of the dive bombers were missing key electrical and mounting components,[nb 61] hampering not only reinforcement of FEAF but limiting flight training of the new pilots.[122] The President Garfield, 500 miles at sea en route to Honolulu,[46] reversed course after receiving word that war had begun in Hawaii and returned to San Francisco. The USAT President Polk, a cargo liner impressed into service as an Army transport, embarked 55 P-40s, an equal number of pilots and ground crews gathered from four groups based in California (including 27 pilots off the President Garfield), and sailed without escort on 18 December, reaching Brisbane on 13 January 1942, where assembly of the P-40s began by the aircraft mechanics of the ground crews.[123] The President Polk embarked the ground echelons of two squadrons of the 7th Bomb Group (based at Jogjakarta)[124] and continued to Java, escorted by the heavy cruiser USS Houston, arriving in Surabaya on 28 January.[125]

By mid-January, Japanese advances southward cut the anticipated aircraft ferry routes to the Philippines and reinforcement was no longer feasible. Instead, using aircraft as their assembly was completed and assigning personnel at hand, provisional fighter squadrons were organized in Brisbane to assist the Royal Netherlands Indies Air Force (ML-KNIL) in defending the NEI. The 17th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) was established on 14 January, and 13 of its 17 pilots had previously been with the 24th PG. With 17 P-40s delivered by the Pensacola convoy (assembly of the 18th could not be completed because of a lack of parts), it flew across northern Australia from Brisbane to Darwin, then to Java via Penfoie Airdrome at Koepang and Den Pasar Field on Bali between 16 and 25 January. Only 12 Warhawks arrived at the designated FEAF fighter base at Ngoro Field, the others lost to accidents, combat, and pilot illness.[126][127][nb 62] The 20th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional), incorporating pilots of the 35th PG, took off from Darwin in 25 P-40s on 2 February, but only 17 reached Java, the remainder shot down over Bali or damaged on the ground by air raids.[128] Likewise, 25 P-40s of the 3rd Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) departed Brisbane, but because of accidents involving novice pilots, only 18 reached Darwin on 8 February. Just nine eventually reinforced Ngoro; an entire flight of eight was lost when it exhausted its fuel after its LB-30 navigation guide aircraft became lost in a storm trying to find Koepang. Survivors of both the 3rd and 20th provisional squadrons were integrated into the 17th PS.[129] The 33rd Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) was en route to Java at Darwin when it was nearly annihilated by a Japanese air raid on 19 February.[130] Of 83 P-40s assembled and flown from Brisbane, only 37 arrived at Ngoro Field,[131] and by 15 February less than 20 could be mustered for operations.

The 91st Bombardment Squadron was re-manned in Brisbane with pilots from the 27th BG, and dispatched eleven A-24s to Java on 11 February, but the Japanese threat to Timor prevented the other two squadrons of the 27th from following. Inadequate facilities at its new airfield near Malang delayed maintenance of the dive bombers and prevented their operational use until 19 February.[132] 32 assembled P-40s were collected at Maylands Airfield near Perth, Western Australia, towed to Fremantle on the night of 19–20 February, and loaded on the flight deck of the seaplane tender USS Langley. The Langley sailed at noon 23 February in convoy for Burma but was immediately diverted for Java, as was the freighter MS Sea Witch soon after, carrying 27 unassembled and crated P-40s destined for the 51st Pursuit Group in China. All of the aircraft aboard Langley were lost when it was sunk on 27 February. 31 of the 33 pilots of the 13th and 33rd Pursuit Squadrons (Provisional) perished in the attack. The Sea Witch reached Tjilatjap harbor the next day but destroyed its cargo to keep the P-40s from being captured by the Japanese.[133]

Operations on Java

On 3 February the Japanese opened a series of air attacks on ABDA bases on Java, and the 19th BG was again caught on the ground, losing five of its B-17s in a raid on Singosari, four of them on the ground.[134] On 20 February, just back from a mission to bomb the invasion force at Bali, seven B-17s of the 19th BG were caught on the ground at Pasirian Field in southeastern Java by Zero strafers while re-arming and five more were destroyed.[135][136][nb 63] Although 38 of the more capable B-17E Flying Fortresses and a dozen LB-30 Liberators incrementally reinforced both heavy bombardment groups of the FEAF, losses were severe and the slow rate of reinforcement was unable to keep pace.[137] Despite dispersal and elaborate camouflage, a lack of antiaircraft artillery and poor warning/communication systems resulted in the loss of 65 FEAF aircraft on the ground alone.[138]

Evacuations of personnel from Java and diversion of resources to India and Australia began 20 February. By 24 February only ten heavy bombers, four A-24 dive bombers, and 13 P-40 fighters remained flyable against Japanese forces. ABDA Command was officially dissolved the next day. The ground echelons of both heavy bomb groups began evacuation by sea on 25 February, while the bombers, carrying up to 20 passengers each, made daily six-hour flights to Broome, Western Australia, an intermediate evacuation point for all aircraft fleeing Java. Malang/Singosari closed on 28 February and Jogjakarta the next night, following the final bomber sorties. 260 men, including the remnants of the 17th Pursuit Squadron, were evacuated by five B-17s and three LB-30s. 35 passengers crammed the final LB-30 that took off at 12:30 am of 2 March. On 3 March, nine Japanese fighters attacked Broome, destroying two of the evacuated B-17s.

Of 61 heavy bombers based on Java, only 23 escaped: 17 B-17Es, three LB-30s, and three of the original B-17Ds of the 19th BG. Only six had been lost in aerial combat, but at least 20 were destroyed on the ground by Japanese attacks.[138] Every fighter (39) and dive bomber (11) that arrived on Java was destroyed. Against these losses, the provisional pursuit squadrons were credited with the destruction of 45 Japanese aircraft in aerial combat.[110][nb 64] Heavy bombers had flown over sixty missions and at least 300 bomber sorties, but 40% of the bombers turned back or otherwise failed to find their targets.[139] Brereton's evacuation to India on 23 February 1942 effectively ended existence of the Far East Air Force, which had been re-designated "5 Air Force" on 5 February. Its headquarters was not re-manned until 18 September 1942 in Australia, when it was designated Fifth Air Force.[140]

Fifth Air Force along with Thirteenth Air Force in the Central Pacific and Seventh Air Force in Hawaii was subsequently assigned to a higher echelon on 3 August 1944, the newly created United States Far East Air Forces also with the acronym FEAF. This FEAF was subordinate to the U.S. Army Forces Far East and served as the headquarters of Allied Air Forces Southwest Pacific Area.

Strength of the FEAF, 8 December 1941

SOURCES: AAF Historical Study No.34, Army Air Forces in the War Against Japan, 1941–1942[54] and Bartsch, 8 December Appendix C[59]

Order of battle

- 5th Bomber Command

- 19th Bomb Group (Heavy) (Headquarters, Clark Field, collectively, 4 B-17C, 15 B-17D, 10 B-18)

The B-17s were distributed eight to a squadron, with three attached to the group headquarters squadron. Four of the B-18s were assigned to Headquarters Squadron, and the others to the 28th BS.- 14th Bomb Squadron (Del Monte Field No. 1, 6 December: 1 B-17C, 7 B-17D)

- 28th Bomb Squadron (Clark Field)

- 30th Bomb Squadron (Clark Field)

- 93rd Bomb Squadron (Del Monte Field No. 1, 6 December: 1 B-17C, 7 B-17D)

- 5th Air Base Group (Del Monte No. 1: 2 B-18)

- 27th Bomb Group (Light) (no assigned aircraft, 3 B-18 attached for training)

- 16th Bomb Squadron (Fort McKinley)

- 17th Bomb Squadron (San Fernando Auxiliary Field)

- 91st Bomb Squadron (San Marcelino Auxiliary Field)

- 10th Bombardment Squadron (Light), Philippine Army Air Corps (Maniquis Field)

- 19th Bomb Group (Heavy) (Headquarters, Clark Field, collectively, 4 B-17C, 15 B-17D, 10 B-18)

- 5th Interceptor Command

- 24th Pursuit Group (Headquarters, Clark Field, collectively 89 P-40B/E, 26 P-35A, 12 P-26A)

- Headquarters Squadron (Clark Field: 1 P-40B)

- 3rd Pursuit Squadron (Iba Field: 24 P-40E, 4 P-35A)

- 17th Pursuit Squadron (Nichols Field: 21 P-40E)

- 20th Pursuit Squadron (Clark Field: 23 P-40B)

- 21st Pursuit Squadron (attached, Nichols Field: 20 P-40E)

- 34th Pursuit Squadron (attached, Del Carmen Field: 22 P-35A)

- 6th Pursuit Squadron, Philippine Army Air Corps (Zablan Field: 12 P-26A)

- 24th Pursuit Group (Headquarters, Clark Field, collectively 89 P-40B/E, 26 P-35A, 12 P-26A)

- 2nd Observation Squadron (Nichols Field: 2 O-46A, 3 O-49, 11 O-52)

(35th Pursuit Group headquarters never arrived in the Philippines and is not listed for that reason.)

Support units and personnel

The August 1941 strength of "Air Force USSAFE" was 2,049 enlisted troops under the command of 254 officers. Final FEAF peacetime strength is disputed. One source stated that, as of 30 November, its strength was 5,609: 669 officers and 4,940 enlisted troops.[141] Another put the 7 December strength as 8,100.[44] The Philippine Army Air Corps constituted another 1,500 members, with units at Maniquis Field (Cabanatuan), Zablan Field (Manila), and an auxiliary strip at Batangas, all on Luzon; and a detachment at Lahug on Cebu.[44]

The numbers in italicized brackets indicate the number of personnel, as of 30 November.

- Hq & Hq Sq, Far East Air Force at Nielson Field (42 off, 1 wo, 136 enl)

- Hq & Hq Sq, 5th Bomber Command at Clark Field (1 off, 20 enl)

- Hq & Hq Sq, Far East Air Service Command at Nielson Field (3 off, 56 enl)

- Philippine Air Depot at Nichols Field (17 off)

- 5th Air Base Group at Del Monte Field (Hq & Hq Sq only)(16 off, 166 enl)

- 20th Air Base Group at Nichols Field (Hq & Hq Sq, 19th Air Base Sq, 27th and 28th Material Sqs)

- 200th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) (Mobile) at Clark Field (76 off,1 wo, 1732 enl)

- 803d Engineer Battalion, Aviation (Separate)

- 7th Materiel Squadron, 19th Bomb Group

- 48th Materiel Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group (216)

- 440th Ordnance Company (Bombardment)

- 701st Ordnance Company (Air Base)[nb 65]

- Other units

- Tow Target detachment (49)

- Weather detachment (20)

- Chemical Warfare detachment (180)

- Air Warning Service, 5th Interceptor Command

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Two B-18s used as transports and the Philippine Air Depot C-39, used to evacuate personnel from Mindanao in April 1942, also escaped.

- ↑ Civil aviation preceded military in the Philippines by more than a year. Three Americans, airplane designers Thomas Scott Baldwin and Tod Shriver, and barnstormer James C. "Bud" Mars, visited the Philippines in early 1911 as part of a 30,000-mile world demonstration tour. Their aircraft were the Skylark, Shriver's 1910 biplane, flown by Mars, and the Red Devil, designed and flown by Baldwin. Both planes had been built by Glenn Curtiss. Baldwin made the first cross-country flight in the Philippines in the Red Devil in February 1911, and sold it to an American resident of the Philippines, who later crashed it.

- ↑ The 1st Company, 2nd Aero Squadron was activated on 12 May 1915 but not organized until December, and sailed from San Francisco on 5 January 1916. It expanded to a full squadron of two companies in July 1917.

- ↑ The five-member Air Board, created in March 1939 during the continuing struggle between the Air Corps and the General Staff over aviation doctrine, reported to Arnold but was dominated by three non-flying general staff officers.

- ↑ Grunert had been in the Philippines since 1935. Before becoming commanding general of the department, he had commanded a regiment, brigade and the division itself in the Philippine Division. His views on the readiness of the Air Corps had been influenced since 1938 by a deputy commander, Henry Conger Pratt, who was the first Air Corps officer to reach the permanent rank of brigadier general.

- ↑ The majority of the 13 fields were civilian in nature, intended for dispersal, and seven were situated on islands other than Luzon.

- ↑ The 20th and 17th arrived in the Philippines on 23 November and 5 December 1940, respectively, with the disassembled P-35s accompanying the latter. No upgrade of the antiaircraft defenses was made for more than a year, and then only a single national guard unit equipped with 12 World War I-vintage guns only slightly more modern than the four already in the islands, all of which were of limited slant range and altitude.

- ↑ Richards was named for his grandfather, Harrison Henry Cocke, who resigned as a captain in the United States Navy after 49 years service to become a commodore in the Virginia/Confederate Navy at the age of 67 and commanded the James River defenses at Petersburg.

- ↑ Third in seniority was Lt. Col. Charles M. Savage, who was on the promotion list to colonel, but he also lacked favor with Grunert, possibly because Savage's command background was in airships, not airplanes.

- ↑ AFHRA's fact sheet for the Fifth Air Force gives the date, in error, as 20 September 1941. Craven and Cate's date (cited from the monograph AAF Reference History No. 11, "Army Air Action in the Philippines and Netherlands East Indies, 1941-42", p.6-10 and reissued as AAF Historical Study No. 34) of 6 May coincides with the assignment of a general officer to command the PDAF. 20 September 1941 is possibly the date that the Army endorsed the Philippine Department's general order organizing the PDAF. Whatever the source of AFHRA's error, by 20 September its name had already been changed to "Air Force, USSAFFE" for a month. (Williams p. 5)

- ↑ The general was known in the service as "Sue" Clagett. A West Point graduate in the class ahead of Chief of Air Corps Major General Henry H. Arnold, he had been a career infantry officer until switching to the Air Service in mid-career during World War I. He had never served in nor commanded troops in combat. Clagett had succeeded Arnold in command of the GHQ Air Force 1st Wing in 1936 after holding a number of Air Corps Training Center commands, which led to his promotion to brigadier general in a wave of Air Corps expansion promotions in October 1940. When selected to command the new PDAF he had been wing commander of the newly-created 6th Pursuit Wing less than three months. His selection by the War Department had come at a time when Arnold was in the dog house with President Roosevelt for vociferously criticizing foreign sales of aircraft at the expense of the Air Corps and in England, struggling to keep from being involuntarily retired. Edmunds described Clagett as "an old-line officer of uncertain health, with a long record of peacetime service and a prodigious knowledge of regulations, which had induced conservative habits of thought and a certain inflexibility of imagination." (Edmunds, p. 19) His poor health, reputation for drinking and possibly his selection by the War Department without input from Arnold ultimately contributed to the AAF chief relieving him from command after just five months. (Miller)

- ↑ "A-27" was the Air Corps designation for T-6 Texan trainers equipped with bomb racks and a gun for sale to Siam. The consignment had been held on the docks in Manila to keep them from being captured and used by the Japanese after the occupation of Indochina in 1940. The PDAF used them as an instrument trainer for the pilots fresh out of pilot training.

- ↑ The instrumentation for the P-35s was in Swedish and for the A-27s in Thai, and both were calibrated in the metric system rather than United States customary units. (December 8, p. 33, Edmunds p. 72)

- ↑ The plant in Manila produced oxygen for Navy use in welding.

- ↑ Six oxygen-producing plants were among new equipment allocated to FEAF. They were en route by sea when war broke out and diverted to Australia. (Edmunds, p. 38)

- ↑ The 4th CG, for example, had three commanders between May and August, then was dissolved.

- ↑ The pursuit squadrons, unable to move their aircraft, were forced to remove propellers, lower the aircraft to the ground with their landing gear raised, then tie down and weight the wings with sandbags to prevent their being lifted by the high winds.

- ↑ The most current model of P-40, the 50 arrived at the Philippine Air Depot on 29 September disassembled and in crates.

- ↑ The 4th CG continued a paper existence until the 28th Bomb Squadron was absorbed into the 19th BG, then was disbanded, with the 2nd Observation Squadron assigned directly to FEAF headquarters.

- ↑ This total includes the complements of the B-17 squadrons and those of the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons, but not those of the 27th BG, who never had flight duties in the Philippines.

- ↑ The AAF decided to use its experienced pilots in the United States as training cadre for newly created units rather than reinforce overseas units. As a result FEAF pilots were unusually young and inexperienced when war began. Pilot levies in 1941 totaled 169 first assignment pilots: 10 February: 24 from Class 40H; 8 May: 39 from Class 41B; 24 June: 68 from Class 41C and 28 from Class 41D; 23 October: 10 from Class 41G. While 22 of the 28 pilots that arrived with the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons on 20 November were from these same classes, they had experience flying P-40 aircraft before deployment to FEAF.

- ↑ The 28th Bomb Squadron had been a longtime part of the 4th Composite Group, which was disbanded on 16 November 1941. The squadron was formally assigned to the 19th BG on that date.

- ↑ On 2 December the 14th BS was re-assigned on paper to the 7th Bomb Group in anticipation of reinforcing it on Mindanao, but the 7th BG never arrived in the Philippines.

- ↑ The shipment of crated P-40Es, fresh from the assembly line, had sailed from San Francisco on 19 October. Another 38 were in transit at sea, having sailed 9 and 15 November, but all but three would never reach the Philippines. (Morton p. 39, Doomed p. 36 )

- ↑ Edmunds points out that barring reinforcement by a sufficient number of B-17Es with their powered gun turrets and tail gun positions (only 170 had been delivered to the AAF by December 1941), the only chance the B-17s of the 19th BG had of survival in combat was flying in mutually-supporting squadron formations. (Edmunds p. 71)

- ↑ Brereton held the same date of rank as Clagett but was significantly younger, healthier, and more experienced in flying operations, including a combat command in World War I. MacArthur was familiar with Brereton from that war and chose him out of three candidates put forth by Arnold.

- ↑ FEAF Bomber Command was commanded by 19th BG commander Col. Eugene Eubank. The position of Air Officer of the Philippine Department was abolished and Richards made a supernumerary staff member of FEAF headquarters. He was captured when Corregidor surrendered and survived 40 months as a prisoner-of-war, although his health was ruined.

- ↑ Losses among the P-40Bs of the 20th PS were particularly severe; fully one-third were written off between their introduction in July and the end of October.

- ↑ Guns of both P-40s and P-35s flown at high altitude became extremely cold, and if not immediately cleaned after landing, suffered in the humid air from condensation that quickly became rust. (Edmunds, p. 32)

- ↑ 27 each of Mitsubishi Ki-21 (Army Type 97) "Sally" and Kawasaki Ki-48 (Army Type 99) "Lily"

- ↑ The Imperial Japanese Navy also employed 12 Mitsubishi A5M (Navy Type 96) "Claude" carrier fighters and 13 Nakajima B5N (Navy Type 97) "Kate" carrier attack bombers off the aircraft carrier Ryūjō for its Mindanao operations, which were unopposed by interceptors or land-based antiaircraft weapons.

- ↑ In addition to a B-17 permanently out of action, its tail knocked off in a landing collision on 12 September during a typhoon, two others of the 19 at Clark were in hangars being painted in camouflage.

- ↑ Includes two assembled P-40Es still at the air depot earmarked for the 21st PS. Three additional P-40Es remained crated.

- ↑ The sole A-27 serviceable on 8 December was with the 3rd PS at Iba. A second was at the Philippine Air Depot for maintenance and later served at Lubao Field.

- ↑ The total number of surviving P-35A airframes is unknown. The 34th PS had 22 in service and the 3rd PS had four.

- ↑ Now the Del Monte Country Club Golf Course.

- ↑ Apparently when this fighter strip became operational, the small strip on the golf course was abandoned and the designation Del Monte No. 3 given to Dalirig. (Doomed, p. 395)

- ↑ Edmunds stated that in a pre-war exercise, 46 minutes elapsed before sightings were reported, plotted, and orders relayed to interceptors to take off to "protect" Clark Field.

- ↑ SCR-270/-271 radars were crude and could only determine direction and distance of approaching aircraft. An experienced operator could sometimes determine by interpretation the approximate size in numbers of the contact. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 6: Men and Planes, p. 96)

- ↑ Radar calibration was a highly technical and laborious process which involved checking every sector of the operating range of a station using plots of controlled flights. To calibrate a single set sometimes required as much as 10,000 miles of flying. Performance tests charted both inner and outer ranges at which targets could be detected and accuracy tests were used to spot errors in azimuth and range. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 6: Men and Planes, p. 98)

- ↑ Six had been shipped to the 60th CA, three to the 200th CA, and two to the 1st Separate Marine Battalion.

- ↑ The radar set of the Marine detachment was the sole survivor.

- ↑ MacArthur's interpretation of this phrase in the war warning had also prohibited pre-war aerial reconnaissance of Japanese airfields, restricting FEAF to a single flight daily by a B-17 that could not proceed beyond the international treaty line between the Philippines and Formosa. However as early as November 26 General Marshall had recommended air reconnaissance of Formosa and ordered two B-24s be sent to FEAF, which MacArthur acknowledged by asking that they photograph Japanese bases in the Palaus en route, which he apparently did not consider an "overt act." (Bartsche December 8, pp. 230 and p. 475 note 4)

- ↑ This was a force of Japanese Army Air Force bombers. Fog had only briefly delayed takeoff from their base at Choshu on southern Formosa. Their target was Camp Hay in northern Luzon, a mountain rest area that MacArthur was known to frequent. (Bartsche December 8, p. 272)

- ↑ Edmunds (p. 88) states that Sutherland in a post-war interview claimed that Brereton disobeyed a direct order from USAFFE to send the entire 19th BG to Del Monte, nor was there any recommendation from Brereton to bomb Japanese airfields. However Bartsche (December 8 pp. 238 and 296), based on USAFFE and FEAF records, states that the dispersal order was issued November 29 in the wake of the war warning from Marshall and cancelled by USAFFE on 2 December because of the pending arrival of the 7th BG at Del Monte; and that although Sutherland insisted that FEAF was authorized only to conduct defensive actions, MacArthur countermanded that personally.

- ↑ 80 Mitsubishi G4M (Navy Type 1) "Betty" and 27 Mitsubishi G3M (Navy Type 96) "Nell".

- ↑ 12 of the 17 B-17s at Clark were destroyed on the ground and three others damaged. Of the four that were unscathed, two were destroyed in ground accidents on the following two days. One of the damaged bombers was later captured and rebuilt by the Japanese. The 3rd and 20th PS—38 P-40s—were completely destroyed at Iba and Clark fields respectively. (Bartsch December 8 p. 442; Doomed p. 133)

- ↑ The Japanese also lost three "Claude" carrier fighters and a "Kate" attack bomber in its attacks at Mindanao.

- ↑ 5th Interceptor Command lost another 23 P-40s and all but five of the P-35s, leaving only 28 P-40s, six of them damaged. Offensvely, including those destroyed at Pearl Harbor (10, including the entire remaining complement of 11th BG bombers, caught on the ground) and five more lost in accidents and combat by the 19th BG, almost 15% of the entire AAF force of 198 B-17s on 7 December were destroyed in the first three days of the war. (Bartsch Doomed, p. 133)

- ↑ Per Edmunds, the 14th and 93rd Squadrons were flown up to Clark and San Marcelino late on 9 December. The next day five B-17s of the 93rd made a squadron attack on Japanese invasion shipping at Vigan in the morning, and in the afternoon the 14th made seven individual attacks at Vigan and Aparri, with two B-17s lost. The 17 survivors of the 19th BG regrouped at Del Monte, where they made six more individual attacks at Vigan on 12 December and three on the invasion force at Legaspi on 14 December, with three bombers lost. Altogether 21 bombing sorties were made and five B-17s destroyed in these operations. After maintenance in Australia, the survivors began four days of operations against Japanese amphibious forces at Davao and Lingayen Gulf, flying 17 sorties, before maintenance needs put all out of commission.

- ↑ An ace in France during World War I, Harold Huston George was known as "Pursuit George" to distinguish him from Harold Lee George ("Bomber George"). Both had been in the Army 24 years. "Pursuit George" had six months' seniority and achieved both his colonelcy and flag rank three months earlier than his bomber counterpart. He was killed in a freak aircraft ground accident in Australia a month after his evacuation.

- ↑ The Philippine Army Air Corps operated throughout this period from Zablan Airfield near Manila, first as an interceptor force until 12 December and then as reconnaissance for infantry units until 24 December. It still had six P-26s remaining in service when it received orders to destroy them and retire into Bataan. (Edmunds, p.147)

- ↑ Demonstrating the effects of pre-war inexperience among the pilots and a lack of quality maintenance, of the nine P-40s displaced from Pilar four were lost in the various movements back and forth from Mindanao.

- ↑ The Japanese Army by 22 January had 36 Mitsubishi Ki-30 (Army Type 97) "Ann" dive bombers, 11 Nakajima Ki-27 (Army Type 97) "Nate" fighters, and 15 Mitsubishi Ki-15 (Army Type 97) "Babs" reconnaissance aircraft based near Bataan.

- ↑ Only six sorties were flown between 3 and 27 March, at which time flight surgeons instituted a nutrition "training table" for 25 pilots of three full meals a day. Missions resumed 2 April.

- ↑ Those rescued included Filipino Col. Carlos Romulo. One of the P-35As landed wheels up just off a beach on Leyte.

- ↑ The 40th RS (soon to be the 435th BS) had been formed in March 1942 from the remnants of 19th Bomb Group after the Java Campaign and equipped with B-17Es. Two of the B-17s bombed Nichols Field and the harbor at Batangas. The Mitchells of the 13th and Bomb Squadrons flew approximately 30 combat sorties in two days with no losses, then returned to Darwin on 14 April, each carrying three passengers evacuating from Mindanao. One of the B-17s was destroyed during a Japanese raid on Del Monte No. 1 when Royce rejected recommendations to disperse the B-17s to one of the camouflaged fields, but the other two returned to Australia transporting evacuees, including Navy Lieut. John D. Bulkeley.

- ↑ The total includes two victories credited to the 6th Pursuit Squadron, PAAC.

- ↑ The figures are for the 1,144 enlisted men of the 5th Interceptor Command, but are representative of the FEAF as a whole.

- ↑ A nationwide roundup of coolant in Australia permitted the initial provisional squadron to stand up on 16 January 1942.

- ↑ The missing gun trigger motors and solenoids had apparently been fixed to their packing crates and destroyed when the crates were burned. The A-24-DEs of the 27th BG were Navy SBD-3s converted for Army use on the factory assembly line and had Navy bomb racks that required modification of the bombs used by the Army. They had been used in pre-war maneuvers so that their engines were already worn, significantly reducing their cruise speed.

- ↑ Also known as Blimbing, Ngoro Field had been an emergency strip first used in 1939. The ML-KNIL upgraded it to a full fighter strip and camouflaged it so expertly it was not discovered by the Japanese until the final day of the campaign.

- ↑ At least one source (Joe Baugher) states that this raid occurred February 22. Of the 14 B-17s that escaped from the Philippines, two were destroyed on the ground at Singosari on February 3 and four more at Pisirian. Four others were written off in accidents. Ultimately only two of the original 35 survived the Philippine and Java campaigns, one of which was B-17D 40-3097, The Swoose. The other, B-17C 40-2072, was converted to a transport after incurring battle damage on a mission to Davao in the Philippines on December 25, 1941, and later crashed while operating in the 317th Troop Carrier Group.

- ↑ Edmunds credits 46. However, Bartsch states that only eight aerial victories by the provisional squadrons can be substantiated. (Edmunds 1951, p. 360, note, Bartsch & Nightmare, p. 337)

- ↑ On 13 December 1941 the ordnance company departed Manila aboard the inter-island steamer Corregidor bound for Del Monte. The ship struck a U.S. mine in Manila Bay and sank with many casualties.

- ↑ The detachment moved to Wawa Beach near Nasugbu on 4 December using trucks borrowed from the Philippine Army because it had no prime mover or tractors of its own. On 10 December it detected the midday raid conducted by the Japanese against Nichols Field and Cavite, and attempted to provide early warning. It was unable to raise its own unit at Sangley Point and could not persuade Army operators on Corregidor to acknowledge the transmission. The detachment moved inland to avoid Japanese landing parties seeking it, and on Christmas Eve began movement to Orani Field on Bataan, where it set up on 8 January. When Japanese advances forced Orani Field to close, the detachment moved south to its final position at Bataan Field, resuming operations on 3 February.

- Citations

- 1 2 Edmunds 1992, pp. 70–71

- ↑ Edmunds 1951, p. 178

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1947, p. 375

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, p. 202

- 1 2 Bartsch & Doomed, p. 428

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1947, p. 225

- ↑ Hennessy 1958, p. 79

- ↑ Hennessy 1958, p. 84

- ↑ Hennessy 1958, pp. 151–152

- ↑ Maurer & Squadrons, p. 15

- ↑ Bartsch 1992, p. 1

- ↑ Maurer & Squadrons, p. 142

- ↑ Maurer & Squadrons, p. 23

- ↑ Maurer & Squadrons, pp. 15, 22, 141

- 1 2 3 Bartsch & December 8, pp. 23–25

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, p. 25

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1947, p. 177

- 1 2 Williams 1945, p. 5

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 70–71, 87

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, pp. 26–27

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 45

- ↑ Bartsch & Doomed, p. 9

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, p. 20

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, p. 60

- 1 2 3 Bartsch & December 8, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 75–76

- 1 2 3 Edmunds 1992, p. 38

- 1 2 Edmunds 1992, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, pp. 108–109

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, p. 108

- ↑ Bartsch & Doomed, p. 15

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, p. 33

- ↑ Bartsch & December 8, p. 118, USAFFE General Order No. 4.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 25

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1947, p. 178

- ↑ Edmunds 1992, p. 35

- ↑ Bartsch & Doomed, p. 23

- ↑ Bartsch & Doomed, p. 21