Verapamil

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /vɜːrˈæpəmɪl/ |

| Trade names | various |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | C08DA01 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35.1% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 2.8-7.4 hours |

| Excretion | Renal: 11% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

52-53-9 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2520 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2406 |

| DrugBank |

DB00661 |

| ChemSpider |

2425 |

| UNII |

CJ0O37KU29 |

| KEGG |

D02356 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:9948 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL6966 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.133 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

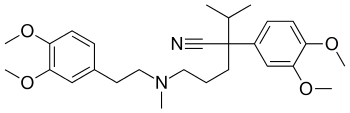

| Formula | C27H38N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 454.602 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Verapamil (sold under various trade names)[1] is a calcium channel blocker used in the treatment of hypertension, angina pectoris, cardiac arrhythmia, and most recently, cluster headaches.[2][3] It is also an effective preventive medication for migraine.[4] Verapamil has also been used as a vasodilator during cryopreservation of blood vessels.

Verapamil is of the phenylalkylamine class. It is a class-IV antiarrhythmic and more effective than digoxin in controlling ventricular rate.[5]

It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 1982.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[7]

Medical uses

Verapamil is also used intra-arterially to treat cerebral vasospasm.[8] Verapamil is used to treat the condition cluster headache.[9] Verapamil is used for controlling ventricular rate in supraventricular tachycardia and migraine headache prevention.[10] Verapamil is not listed as a first line agent by the guidelines provided by JAMA in JNC-8.[11] However, it may be used to treat hypertension if patient has co-morbid atrial fibrillation or other types of arrhythmia.[2]

Contraindication

Use of verapamil is generally avoided in people with severe left ventricular dysfunction, hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg), cardiogenic shock, and hypersensitivity to verapamil.[12]

Side effects

The most common side effect of Verapamil is constipation (7.3%). Other side effects include: dizziness (3.3%), nausea (2.7%), low blood pressure (2.5%), and headache 2.2%. Other side effects seen in less than 2% of the population include: edema, congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, fatigue, elevated liver enzymes, shortness of breath, low heart rate, atrioventricular block, rash and flushing.[13]

Along with other calcium channel blockers, verapamil is known to induce gingival hyperplasia. [14]

Overdose

Acute overdose is often manifested by nausea, asthenia, bradycardia, dizziness, hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmia. Plasma, serum, or blood concentrations of verapamil and norverapamil, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. Blood or plasma verapamil concentrations are usually in a range of 50-500 μg/l in persons on therapy with the drug, but may rise to 1–4 mg/l in acute overdose patients and are often at levels of 5–10 mg/l in fatal poisonings.[15][16]

Mechanism of action

Verapamil's mechanism in all cases is to block voltage-dependent calcium channels.[12] In cardiac pharmacology, calcium channel blockers are considered class-IV antiarrhythmic agents. Since calcium channels are especially concentrated in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, these agents can be used to decrease impulse conduction through the AV node, thus protecting the ventricles from atrial tachyarrhythmias.

Calcium channels are also present in the smooth muscle lining blood vessels. By relaxing the tone of this smooth muscle, calcium channel blockers dilate the blood vessels. This has led to their use in treating high blood pressure and angina pectoris. The pain of angina is caused by a deficit in oxygen supply to the heart. Calcium channel blockers like verapamil dilate blood vessels, which increases the supply of blood and oxygen to the heart.[17] This controls chest pain, but only when used regularly. It does not stop chest pain once it starts. A more powerful vasodilator such as nitroglycerin may be needed to control pain once it starts.

Pharmacokinetic details

More than 90% of verapamil is absorbed when given orally,[12] but due to high first-pass metabolism, bioavailability is much lower (10–35%). It is 90% bound to plasma proteins and has a volume of distribution of 3–5 l/kg. It takes 1 to 2 hours to reach peak plasma concentration after oral administration.[12] It is metabolized in the liver to at least 12 inactive metabolites (though one metabolite, norverapamil, retains 20% of the vasodilating activity of the parent drug). As its metabolites, 70% is excreted in the urine and 16% in feces; 3–4% is excreted unchanged in urine. This is a nonlinear dependence between plasma concentration and dosage. Onset of action is 1–2 hours after oral dosage. Half-life is 5–12 hours (with chronic dosages). It is not cleared by hemodialysis. It is excreted in human milk. Because of the potential for adverse reaction in nursing infants, nursing should be discontinued while verapamil is administered.

Verapamil has been reported to be effective in both short-term[18] and long-term treatment of mania and hypomania.[19] Addition of magnesium oxide to the verapamil treatment protocol enhances the antimanic effect.[20] It has on occasion been used to control mania in pregnant patients, especially in the first three months. It does not appear to be significantly teratogenic. For this reason, when one wants to avoid taking valproic acid (which is high in teratogenicity) or lithium (which has a small but significant incidence of causing cardiac malformation), verapamil is usable as an alternative, albeit presumably a less effective one.

Veterinary use

Intra-abdominal adhesions are common in rabbits following surgery. Verapamil can be given postoperatively in rabbits which have suffered trauma to abdominal organs to prevent formation of these adhesions.[21][22][23] Such effect was not documented in another study with ponies.[24]

Uses in cell biology

Verapamil is also used in cell biology as an inhibitor of drug efflux pump proteins such as P-glycoprotein.[25] This is useful, as many tumor cell lines overexpress drug efflux pumps, limiting the effectiveness of cytotoxic drugs or fluorescent tags. It is also used in fluorescent cell sorting for DNA content, as it blocks efflux of a variety of DNA-binding fluorophores such as Hoechst 33342. Radioactively labelled verapamil and positron emission tomography can be used with to measure P-glycoprotein function.[26]

Research

As of 2015, a clinical trial of verapamil in diabetes was under way.[27]

Trade names

Verapamil is sold under many trade names worldwide.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 Drugs.com International trade names for Verapamil Page accessed Jan 14, 2015

- 1 2 Koda-Kimble and Young's Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. USA: LWW; Tenth, North American Edition edition. 2012. pp. 320–322,. ISBN 1609137132.

- ↑ "Management of Cluster Headache - American Family Physician". www.aafp.org. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Koda-Kimble and Young's Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. USA: LWW; Tenth, North American Edition edition. 2012. p. 1340. ISBN 1609137132.

- ↑ Srinivasan, Viswanathan; Sivaramakrishnan, H; Karthikeyan, B (2011). "Detection, Isolation and Characterization of Principal Synthetic Route Indicative Impurities in Verapamil Hydrochloride". Scientia Pharmaceutica. 79 (3): 555–68. doi:10.3797/scipharm.1101-19. PMC 3163365

. PMID 21886903.

. PMID 21886903. - ↑ "verapamil, Calan, Verelan, Verelan PM, Isoptin, Covera-HS". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Jun, P.; Ko, N. U.; English, J. D.; Dowd, C. F.; Halbach, V. V.; Higashida, R. T.; Lawton, M. T.; Hetts, S. W. (2010). "Endovascular Treatment of Medically Refractory Cerebral Vasospasm Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 31 (10): 1911–6. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2183. PMID 20616179.

- ↑ Drislane, Frank; Benatar, Michael; Chang, Bernard S.; Acosta, Juan; Tarulli, Andrew (1 January 2009). Blueprints Neurology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7817-9685-9. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ↑ Koda-Kimble and Young's Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs 10th edition. USA: LWW. 2012. pp. 497, 1349. ISBN 1609137132.

- ↑ "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (jnc 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–520. 2014-02-05. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 24352797.

- 1 2 3 4 "CALAN (verapamil) Packet Insert" (PDF).

- ↑ "G.D. Searle LLC Division of Pfizer Inc". CALAN- verapamil hydrochloride tablet, Package Insert. Pfizer. October 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ Steele, RM; Schuna, AA; Schreiber, RT (1994). "Calcium antagonist-induced gingival hyperplasia". Annals of Internal Medicine. 120 (8): 663–4. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-120-8-199404150-00006. PMID 8135450.

- ↑ Wilimowska, Jolanta; Piekoszewski, Wojciech; Krzyanowska-Kierepka, Ewa; Florek, Ewa (2006). "Monitoring of Verapamil Enantiomers Concentration in Overdose". Clinical Toxicology. 44 (2): 169–71. doi:10.1080/15563650500514541. PMID 16615674.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, California: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1637–9.

- ↑ "DailyMed - VERAPAMIL HYDROCHLORIDE - verapamil hydrochloride tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ; Houser Jr, WL; Loiselle, RH; Giannini, MC; Price, WA (1984). "Antimanic effects of verapamil". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (12): 1602–3. PMID 6439057.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ; Taraszewski, R; Loiselle, RH (1987). "Verapamil and lithium in maintenance therapy of manic patients". Journal of clinical pharmacology. 27 (12): 980–2. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb05600.x. PMID 3325531.

- ↑ Giannini, A.James; Nakoneczie, Ann M.; Melemis, Stephen M.; Ventresco, James; Condon, Maggie (2000). "Magnesium oxide augmentation of verapamil maintenance therapy in mania". Psychiatry Research. 93 (1): 83–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00116-X. PMID 10699232.

- ↑ Elferink, Jan G.R.; Deierkauf, Martha (1984). "The effect of verapamil and other calcium antagonists on chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes". Biochemical Pharmacology. 33 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90367-8. PMID 6704142.

- ↑ Azzarone, Bruno; Krief, Patricia; Soria, Jeannette; Boucheix, Claude (1985). "Modulation of fibroblast-induced clot retraction by calcium channel blocking drugs and the monoclonal antibody ALB6". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 125 (3): 420–6. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041250309. PMID 3864783.

- ↑ Steinleitner, Alex; Lambert, Hovey; Kazensky, Carol; Sanchez, Ignacio; Sueldo, Carlos (1990). "Reduction of primary postoperative adhesion formation under calcium channel blockade in the rabbit". Journal of Surgical Research. 48 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1016/0022-4804(90)90143-P. PMID 2296179.

- ↑ Baxter, Gary M.; Jackman, Bradley R.; Eades, Susan C.; Tyler, David E. (1993). "Failure of Calcium Channel Blockade to Prevent Intra-abdominal Adhesions in Ponies". Veterinary Surgery. 22 (6): 496–500. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.1993.tb00427.x. PMID 8116206.

- ↑ Bellamy, W T (1996). "P-Glycoproteins and Multidrug Resistance". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 36: 161–83. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.001113. PMID 8725386.

- ↑ Luurtsema, Gert; Windhorst, Albert D.; Mooijer, Martien P.J.; Herscheid, Jacobus D.M.; Lammertsma, Adriaan A.; Franssen, Eric J.F. (2002). "Fully automated high yield synthesis of (R)- and (S)-[11C]verapamil for measuring P-glycoprotein function with positron emission tomography". Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 45 (14): 1199–207. doi:10.1002/jlcr.632.

- ↑ "Verapamil for Beta Cell Survival Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes". www.ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-29.