Verona

| Verona | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Città di Verona | ||

|

A collage of Verona, clockwise from top left to right: View of Piazza Bra from Verona Arena, House of Juliet, Verona Arena, Ponte Pietra at sunset, Statue of Madonna Verona's fountain in Piazza Erbe, view of Piazza Erbe from Lamberti Tower | ||

| ||

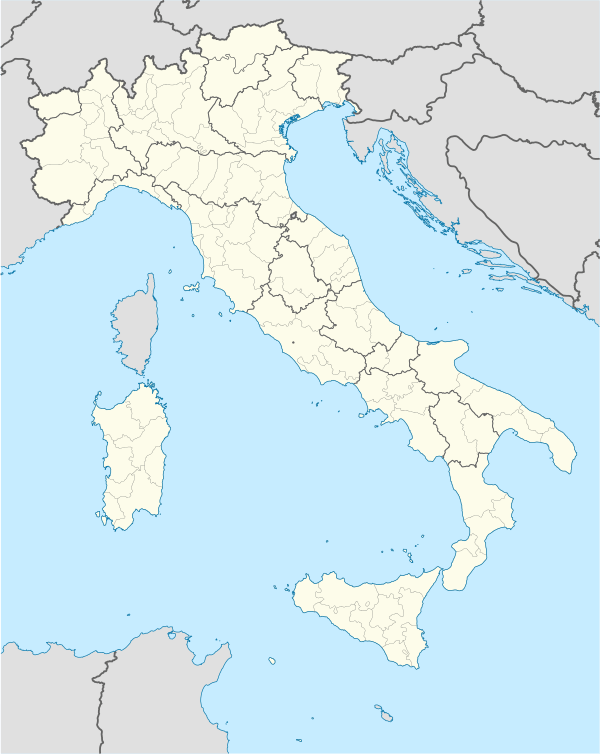

Verona Location of Verona in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 45°26′N 10°59′E / 45.433°N 10.983°ECoordinates: 45°26′N 10°59′E / 45.433°N 10.983°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Veneto | |

| Province / Metropolitan city | Verona (VR) | |

| Frazioni | Avesa, San Michele Extra, San Massimo all'Adige, Quinzano, Quinto di Valpantena, Poiano di Valpantena, Parona di Valpolicella, Montorio Veronese, Mizzole, Marchesino, Chievo, Cà di David e Moruri | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Flavio Tosi | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 206.63 km2 (79.78 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 59 m (194 ft) | |

| Population (2015) | ||

| • Total | 259,069 | |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,200/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Veronesi or Scaligeri | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 37100 | |

| Dialing code | 045 | |

| Patron saint | Saint Zeno of Verona | |

| Saint day | 12 April | |

| Website | Official website | |

| City of Verona | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Reference | 797 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2000 (24th Session) |

.jpg)

Verona (Italian pronunciation: [veˈroːna]; Venetian: Verona, Veròna) is a city on the Adige river in Veneto, northern Italy, with approximately 265,000 inhabitants and one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the second largest city municipality in the region and the third largest in northeast Italy. The metropolitan area of Verona covers an area of 1,426 km2 (550.58 sq mi) and has a population of 714,274 inhabitants.[1] It is one of the main tourist destinations in northern Italy, owing to its artistic heritage, several annual fairs, shows, and operas, such as the lyrical season in the Arena, the ancient amphitheatre built by the Romans.

Three of Shakespeare's plays are set in Verona: Romeo and Juliet, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and The Taming of the Shrew. It is unknown if Shakespeare ever visited Verona or Italy at all, but his plays have lured many visitors to Verona and surrounding cities many times over. The city has been awarded World Heritage Site status by UNESCO because of its urban structure and architecture.

Etymology

The etymology of the name "Verona" is unknown. It may be derived from Vera, perhaps an Etruscan person's name; or it might be of Gallic origin; it may be the name of a Roman family or come from the Latin "ver", meaning "spring". But according to one legend the legendary founder of the city, the Gallic chieftain Brenno, called the new inhabited centre "Vae Roma", that is "Accursed Rome", which then over the centuries became Verona.[2]

Another theory is that it is connected to the river. "Vera" was a name of the river Adige previously to the adoption of the current name. As in many similar instances in Europe the name of the town is formed with the addition of suffix -ona which means settlement over.

The city was sometimes archaically known as "Welsch-Bern" in German.

History

The precise details of Verona's early history remain a mystery. One theory is it was a city of the Euganei, who were obliged to give it up to the Cenomani (550 BC). With the conquest of the Valley of the Po the Veronese territory became Roman (about 300 BC). Verona became a Roman colonia in 89 BC, and then a municipium in 49 BC when its citizens were ascribed to the Roman tribe Poblilia or Publicia.

The city became important because it was at the intersection of several roads. Stilicho defeated Alaric and his Visigoths here in 403. But, after Verona was conquered by the Ostrogoths in 489, the Gothic domination of Italy began. Theoderic the Great was said to have built a palace there. It remained under the power of the Goths throughout the Gothic War (535–552), except for a single day in 541, when the Byzantine officer Artabazes made an entrance. The defections that took place among the Byzantine generals with regard to the booty made it possible for the Goths to regain possession of the city. In 552 Valerian vainly endeavored to enter the city, but it was only when they were fully overthrown that the Goths surrendered it.

In 569, it was taken by Alboin, King of the Lombards, in whose kingdom it was, in a sense, the second most important city. There, Alboin himself was killed by his own wife in 572. The dukes of Treviso often resided there. At Verona Adalgisus, son of Desiderius, in 774 made his last desperate resistance to Charlemagne, who had destroyed the Lombard kingdom. Verona was then the ordinary residence of the kings of Italy, the government of the city becoming hereditary in the family of Count Milo, progenitor of the counts of San Bonifacio. From 880 to 951 the two Berengarii resided there. Otto I ceded to Verona the marquisate dependent on the Duchy of Bavaria.

When Ezzelino III da Romano was elected podestà, in 1226, he was able to convert the office into a permanent lordship, and in 1257 he caused the slaughter of 11,000 Paduans on the plain of Verona (Campi di Verona). Upon his death the Great Council elected as podestà Mastino I della Scala, and he converted the "signoria" into a family possession, though leaving the burghers a share in the government. Failing to be re-elected podestà in 1262, he effected a coup d'état, and was acclaimed capitano del popolo, with the command of the communal troops. It was not without long internal discord that he succeeded in establishing this new office, to which was attached the function of confirming the podestà. In 1277, Mastino dello Scala was killed by the faction of the nobles.

The reign of his son Alberto as capitano (1277–1302) was one incessant war against the counts of San Bonifacio, who were aided by the House of Este. Of his sons, Bartolomeo, Alboino and Cangrande I, only the last shared the government (1308); he was great as warrior, prince, and patron of the arts; he protected Dante, Petrarch, and Giotto. By war or treaty, he brought under his control the cities of Padua (1328), Treviso (1308) and Vicenza. At this time before the Black death the city was home to more than 40,000 people.[3]

Cangrande was succeeded by Mastino II (1329–1351) and Alberto, sons of Alboino. Mastino continued his uncle's policy, conquering Brescia in 1332 and carrying his power beyond the Po. He purchased Parma (1335) and Lucca (1339). After the King of France, he was the richest prince of his time. But a powerful league was formed against him in 1337 – Florence, Venice, the Visconti, the Este, and the Gonzaga. After a three years war, the Scaliger dominions were reduced to Verona and Vicenza (Mastino's daughter Regina-Beatrice della Scala married to Barnabò Visconti). Mastino's son Cangrande II (1351–1359) was a cruel, dissolute, and suspicious tyrant; not trusting his own subjects, he surrounded himself with Brandenburg mercenaries. He was killed by his brother Cansignorio (1359–1375), who beautified the city with palaces, provided it with aqueducts and bridges, and founded the state treasury. He also killed his other brother, Paolo Alboino. Fratricide seems to have become a family custom, for Antonio (1375–87), Cansignorio's natural brother, slew his brother Bartolomeo, thereby arousing the indignation of the people, who deserted him when Gian Galeazzo Visconti of Milan made war on him. Having exhausted all his resources, he fled from Verona at midnight (19 October 1387), thus putting an end to the Scaliger domination, which, however, survived in its monuments.

The year 1387 is also the year of the famous Battle of Castagnaro, between Giovanni Ordelaffi, for Verona, and John Hawkwood, for Padua, who was the winner.

Antonio's son Canfrancesco attempted in vain to recover Verona (1390). Guglielmo (1404), natural son of Cangrande II, was more fortunate; with the support of the people, he drove out the Milanese, but he died ten days after, and Verona then submitted to Venice (1405). The last representatives of the Scaligeri lived at the imperial court and repeatedly attempted to recover Verona by the aid of popular risings.

From 1508 to 1517, the city was in the power of the Emperor Maximilian I. There were numerous outbreaks of the plague, and in 1629–33 Italy was struck by its worst outbreak in modern times. Around 33,000 people died in Verona (over 60 per cent of the population at the time) in 1630–1631.[4]

In 1776 was developed a method of bellringing called Veronese bellringing art. Verona was occupied by Napoleon in 1797, but on Easter Monday the populace rose and drove out the French. It was then that Napoleon made an end of the Venetian Republic. Verona became Austrian territory when Napoleon signed the Treaty of Campo Formio in October 1797. The Austrians took control of the city on 18 January 1798. It was taken from Austria by the Treaty of Pressburg in 1805 and became part of Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy, but was returned to Austria following Napoleon's defeat in 1814, when it became part of the Austrian-held Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. In 1866, following the Six Weeks War, Verona, along with the rest of Venetia, became part of Italy.

The advent of fascism added another dark chapter to the annals of Verona. As throughout Italy, the Jewish population was hit by the Manifesto of Race, a series of anti-Semitic laws passed in 1938, and after the invasion by Nazi Germany in 1943, deportations to Nazi concentration camps. An Austrian Fort (now a church, the Santuario della Madonna di Lourdes), was used to incarcerate and torture Allied troops, Jews and anti-fascists, especially after 1943, when Verona became part of the Italian Social Republic.

As in Austrian times, Verona became of great strategic importance to the regime. Galeazzo Ciano, Benito Mussolini's son-in-law, was accused of plotting against the republic; in a show trial staged by the Nazi and fascist hierarchy at Castelvecchio (the Verona trial), Ciano was executed on the banks of the Adige with many other officers on what is today Via Colombo. This marked another turning point in the escalation of violence that would only end with the final liberation by allied troops and partisans in 1945.

After World War II, as Italy entered into NATO, Verona once again acquired its strategic importance, due to its closeness to the Iron Curtain. The city became the seat of SETAF (South European Allied Terrestrial Forces) and had during the whole duration of the Cold War period a strong military presence, especially American, which is decreasing only in these recent years. Now Verona is an important and dynamic city, very active in terms of economy, and also a very important tourist attraction because of its history, where the Roman past lives side by side with the Middle Age Verona, which in some senses brings about its architectural and artistic motifs.

Climate

Verona has a humid subtropical climate characteristic of Northern Italy's inland plains, with hot summers and cold, humid winters, even though Lake Garda's almost-Mediterranean climate has a partial influence on the city.[5] The relative humidity is high throughout the year, especially in winter when it causes fog, mainly from dusk until late morning, although the phenomenon has become increasingly less frequent in recent years.

| Climate data for Verona (1971–2000, extremes 1946–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.2 (81) |

31.8 (89.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.4 (97.5) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.1 (43) |

8.9 (48) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.2 (63) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.8 (83.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.2 (63) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.8 (64) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.4 (−1.1) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−2.2 (28) |

0.0 (32) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50.9 (2.004) |

43.3 (1.705) |

48.7 (1.917) |

70.4 (2.772) |

74.2 (2.921) |

87.2 (3.433) |

62.6 (2.465) |

81.7 (3.217) |

76.2 (3) |

91.0 (3.583) |

64.8 (2.551) |

52.5 (2.067) |

803.5 (31.634) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 82.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 78 | 73 | 75 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 74 | 76 | 81 | 84 | 84 | 77 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico (humidity 1961–1990)[6][7][8] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In 2009, there were 265,368 people residing in Verona, located in the province of Verona, Veneto, of whom 47.6% were male and 52.4% were female. Minors (children aged 0–17) totalled 16.05% of the population compared to pensioners who number 22.36%. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06%(minors) and 19.94%(pensioners). The average age of Verona residents is 43 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Verona grew by 3.05%, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.85%.[9] The current birth rate of Verona is 9.24 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

As of 2009, 87% of the population was Italian.[10] The largest immigrant group comes from other European nations (the largest coming from Romania): 3.60%, South Asia: 2.03%, and sub-saharan Africa 1.50%. The city is predominantly Roman Catholic, but due to immigration now has some Orthodox Christian, and Muslim followers.

| 2012 largest resident foreign-born groups[11] | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | Population |

| | 7,109 |

| | 5,648 |

| | 3,436 |

| | 1,757 |

| | 1,691 |

| | 1,617 |

| | 1,467 |

| | 1,138 |

Main sights

Because of the value and importance of its many historical buildings, Verona has been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Verona preserved many ancient Roman monuments, no longer in use, in the early Middle Ages, but much of this and much of its early medieval edifices were destroyed or heavily damaged by the earthquake of 3 January 1117, which led to a massive Romanesque rebuilding. The Carolingian period Versus de Verona contains an important description of Verona in the early medieval era.

Roman edifices

The Roman military settlement in what is now the centre of the city was to expand through the cardines and decumani that intersect at right angles. This structure has been kept to the present day and is clearly visible from the air. Further development has not reshaped the original map. Though the Roman city with its basalt-paved roads is mostly hidden from view it stands virtually intact about 6 m below the surface. Most palazzi and houses have cellars built on Roman artifacts that are rarely accessible to visitors. Piazza delle Erbe, near the Roman forum was rebuilt by Cangrande I and Cansignorio della Scala I, lords of Verona, using material (such as marble blocks and statues) from Roman spas and villas.

Verona is famous for its Roman amphitheatre, the Arena, found in the city's largest piazza, the Piazza Bra. Completed around 30 AD, it is the third largest in Italy after Rome's Colosseum and the arena at Capua. It measures 139 metres long and 110 metres wide, and could seat some 25,000 spectators in its 44 tiers of marble seats. The ludi (shows and gladiator games) performed within its walls were so famous that they attracted spectators from far beyond the city. The current two-story façade is actually the internal support for the tiers; only a fragment of the original outer perimeter wall in white and pink limestone from Valpolicella, with three stories remains.The interior is very impressive and is virtually intact, and has remained in use even today for public events, fairs, theatre and open-aired opera during warm summer nights.

There is also a variety of other Roman monuments to be found in the town, such as the Roman theatre of Verona. This theatre was built in the 1st century BC, but through the ages had fallen in disuse and had been built upon to provide housing. In the 18th century Andrea Monga, a wealthy Veronese, bought all the houses that in time had been built over the theatre, demolished them, and saved the monument. Not far from it is the Ponte di Pietra ("Stone Wall Bridge"), another Roman landmark that has survived to this day.

The Arco dei Gavi (Gavi Arch) was built in the 1st century AD, and is famous for having the name of the builder (architect Lucius Vitruvius Cordone) engraved on it, a rare case in the architecture of the epoque. It originally straddled the main Roman road into the city, now the Corso Cavour. It was demolished by French troops in 1805 and rebuilt in 1932.

.jpg)

Nearby is the Porta Borsari, an archway at the end of Corso Porta Borsari. This is the façade of a 3rd-century gate in the original Roman city walls. The inscription is dated 245 AD and gives the city name as Colonia Verona Augusta. Corso Porta Borsari, the road passing through the gate is the original Via Sacra of the Roman city. Today, it is lined with several Renaissance palazzi and the ancient Church of Santi Apostoli, a few metres from Piazza delle Erbe.

Porta Leoni is the 1st century BC ruin of what was once part of the Roman city gate. A substantial portion is still standing as part of the wall of a medieval building. The street itself is an open archaeological site, and the remains of the original Roman street and gateway foundations can be seen a few feet below the present street level. As can be seen from there, the gate contains a small court guarded by towers. Here, carriages and travelers were inspected before entering or leaving the city.

Medieval architecture

- The Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore is Romanesque style church, the third such structure on its site, built from 1123–1135, over the 4th-century shrine to Verona's patron saint, St. Zeno (died 380). The façade dominates the large square, and is flanked with a beautiful 72 metres tall bell tower, which is mentioned by Dante in Canto 18 of Purgatory in the Divine Comedy. The weathered Veronese stone gives a warm golden glow, and the restrained lines of the pillars, columns, and cornices, and the gallery with its double windows, give the façade an air of harmonious elegance. The huge rose window is decorated as a Wheel of Fortune. The lintels above the portal have carvings of the months of the year. Each side of the doorway is embellished with 18 bas-relief panels of biblical scenes, and the inner bronze door panels have 48 primitive but forceful depictions of Biblical scenes and episodes from the life of St Zeno. The meaning of some of the scenes is now unknown, but the extraordinarily vivid energy of the figures is a superb blend of traditional and Ottonian influences. The interior of the church is divided into the Lower Church, occupying about ⅔ of the structure, and the Upper Church, occupying the remainder. The walls are covered with 12th and 14th century frescos and the ceiling of the nave is a magnificent example of a ship's keel ceiling. The vaulted crypt contains the tomb of St. Zeno, the first Bishop of Verona, as well as the tombs of several other saints. North of the church is a pleasant cloister. The church also houses the tomb of King Pippin of Italy (777–810).

- The Basilica of San Lorenzo is another Romanesque church, albeit smaller. It dates from around 1177, but was built on the site of a Paleochristian church, fragments of which remain. The church is built of alternating tracks of brick and stone, and has two cylindrical towers, housing spiral staircases to the women's galleries. The interior is sober, but still quiet. The striped bands of stone and brick and the graceful arches complement the setting.

- Santa Maria Antica is a huge Romanesque church that served as the parish church of the Scaligeri clan, and is famous for the Gothic Scaliger Tombs. The Duomo is also a notable Romanesque church.

- Sant'Anastasia is a huge and lofty church built from 1290–1481 by the Dominicans to hold the massive congregations attracted by their sermons. The Pellegrini chapel houses the famous fresco St. George and the Princess of Trebizond by Pisanello as well as the grave of Wilhelm von Bibra. An art festival is held in the square each may.

With a span length of 48.70 m (159.78 ft), the segmental arch bridge Ponte Scaligero featured, at the time of its completion in 1356, the world's largest bridge arch.

Notable people

- Aleardo Aleardi, a poet

- Paolo Bellasio, composer of the Renaissance; member of the Roman School

- Stefano Bernardi, baroque composer

- Massimo Bubola, singer-songwriter born in Terrazzo

- Paolo Caliari, well known as "Veronese" painter

- Mario Capecchi, Nobel prize in Medicine, 2007

- Giovanni Francesco Caroto, painter

- Catullus, Latin poet

- Walter Chiari, actor

- Gigliola Cinquetti, singer who brought Italy its first Eurovision Song Contest win in 1964

- Damiano Cunego, former world number 1 cyclist and former Giro d'Italia winner

- Franco Donatoni, composer

- Gino Fano, mathematician

- Girolamo Fracastoro, also known as Fracastorius, renowned scholar, physician and poet

- Giovanni Giocondo, architect and scholar

- Girolamo dai Libri, illuminator of manuscripts and painter

- Romano Guardini, theologian

- Marc' Antonio Ingegneri, composer, teacher of Claudio Monteverdi

- Ernestine von Kirchsberg, Austrian landscape painter

- Cesare Lombroso, criminologist

- Scipione Maffei, writer and historian

- Matteo Manassero, British amateur golf champion, 2009

- Arnoldo Mondadori, editor

- Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet, fictional characters from the well known Shakespearian play Romeo and Juliet

- Marcantonio Negri, Baroque composer, associate of Monteverdi

- Carlo Pedrotti, 19th-century composer, conductor, voice teacher and opera administrator

- St. Peter Martyr, Dominican preacher and Saint.

- Ippolito Pindemonte, poet

- Ratherius, Medieval bishop and writer

- Francesca Rettondini, actress

- Vincenzo Ruffo, composer of the Renaissance

- Emilio Salgari, novelist

- Antonio Salieri, composer

- Michele Sammicheli, architect

- Sara Simeoni, former world high jump primatist and Olympic gold medalist

- Marco Stroppa, composer

- Bartolomeo Tromboncino, composer of the Renaissance period

- Giorgio Zancanaro, baritone

Verona was the birthplace of Catullus, and the town that Julius Caesar chose for relaxing stays. It has had an association with many important people and events that have been significant in the history of Europe, such as Theoderic the Great, king of Ostrogoths, Alboin and Rosamund, the Lombard Dukes, Charlemagne and Pippin of Italy, Berengar I, and Dante. Conclaves were held here, as were important congresses. Verona featured in the travel diaries of Goethe, Stendhal, Paul Valéry and Michel de Montaigne.

Sport

The city has three professional football teams. Historically, the city's major team has been Hellas Verona. Hellas Verona won the Italian Serie A championship in 1984-85, and played in the European Cup the following year. Chievo Verona represents Chievo a suburb of Verona. As of the 2016-17 season, only Chievo plays in the first division of Italian football, Serie A, while Hellas plays in the second tier. The teams contest the Derby della Scala and share the 38,402-seater Stadio Marcantonio Bentegodi, which was used as a venue at the 1990 FIFA World Cup. Virtus Vecomp Verona are another Verona-based football club.

Verona is home to the volleyball team Marmi Lanza Verona (now in Serie A1), the rugby team Franklin and Marshall Cus Verona Rugby (now in Serie A1), and the basketball team Scaligera Basket (now in Legadue).

The city has twice hosted the UCI Road World Championships, in 1999 (with Treviso as co-host) and in 2004. The city also regularly hosts stages of the Giro d'Italia annual cycling race. Verona also hosted the baseball world cup in 2009, and the Volleyball World Cup in September–October 2010. Verona is hosting the Volleyball Women's World Championship in September–October 2014.[12]

Infrastructure and transport

Buses

Buses are operated by the provincial public transport company, Azienda Trasporti Verona (ATV).

Railways

Verona lies at a major route crossing where the north-south rail line from the Brenner Pass to Rome intersects with the east-west line between Milan and Venice, giving the city rail access to most of Europe. The city is, therefore, served by international, regional and local services.

Verona's main station is Verona Porta Nuova railway station, to the south of the city centre. It is considered to be the ninth busiest railway station in Italy, handling approximately 68,000 passengers per day, or 25 million passengers per year.[13]

There is a lesser station to the east of the city at Porta Vescovo, which used to be the main station in Verona, but now only receives trains between Venice and Porta Nuova.

Airport

Verona Airport is located 5.0 km (3.1 mi) southwest of Verona. It handles around 3 million passengers per year. It is linked to Porta Nuova railway station by a frequent bus service.[13]

There are direct flights between Verona and Rome Fiumicino, Munich, Berlin, Moscow, Naples, Frankfurt, Catania, Paris Charles De Gaulle, London Gatwick, Dublin, Palermo, Manchester, Vienna Schwechat, Liverpool[14] and Cagliari among others.

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Verona has several twin towns, sister cities and partnerships around the world. Some are thematic:

Pula, Croatia, has a similar Roman amphitheatre[15]

Pula, Croatia, has a similar Roman amphitheatre[15] Nîmes, France, has a similar Roman amphitheatre

Nîmes, France, has a similar Roman amphitheatre Munich, Germany

Munich, Germany Salzburg, Austria

Salzburg, Austria Ra'anana, Israel, since 1998[16]

Ra'anana, Israel, since 1998[16] Mashhad, Iran

Mashhad, Iran Ningbo, China [17]

Ningbo, China [17].svg.png) Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, Belgium

Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, Belgium Košice, Slovakia, since 1992[18]

Košice, Slovakia, since 1992[18] Bethlehem, Palestine, since 1998[19]

Bethlehem, Palestine, since 1998[19] Nagahama, Japan

Nagahama, Japan Fresno, California, USA

Fresno, California, USA Albany, New York, USA

Albany, New York, USA Batumi, Georgia[20]

Batumi, Georgia[20] Corfu, Greece[21]

Corfu, Greece[21] Detmold, Germany

Detmold, Germany Korça, Albania[22]

Korça, Albania[22] Ayacucho, Peru

Ayacucho, Peru Lecce, Italy

Lecce, Italy

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Tales of Verona"

- ↑ http://www.italyguides.it/us/italy/veneto/verona/verona.htm

- ↑ David Abulafia, Short Oxford History of Italy: Italy in the Central Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ↑ "Epidemics and pandemics: their impacts on human history". J. N. Hays (2005). p.103. ISBN 1-85109-658-2

- ↑ Thomas A. Blair, Climatology: General and Regional, Prentice Hall pages 131-132; Adriana Rigutti, Meteorologia, Giunti, p, 95, 2009.

- ↑ "Verona/Villafranca (VR)" (PDF). Atlante climatico. Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ "STAZIONE 090-VERONA VILLAFRANCA: medie mensili periodo 61 - 90". Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Verona Villafranca: Record mensili dal 1946" (in Italian). Servizio Meteorologico dell’Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ↑ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ http://www.comuni-italiani.it/023/091/statistiche/stranieri.html

- ↑ "Volleyball Women's World Championship 2014". FIVB. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Trains to and from Verona Airport (VRN)". Italian Airport Guide. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ Liverpool - Verona Archived 8 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Međunarodna suradnja Grada Pule". Grad Pula (in Croatian and Italian). Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Ra'anana: Twin towns & Sister cities – Friends around the World". raanana.muni.il. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ↑ "Sino-Italian love culture fest held in Verona". Xinhua New Agency. 25 September 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Twin cities of the City of Kosice". Magistrát mesta Košice, Tr. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Twinning with Palestine". Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Batumi - Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Batumi City Hall. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "AllCorfu.Com: Corfu's Twin Cities". allcorfu.com. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ Korçë Municipality. "Twin cities" (in Albanian). Korçë Municipality. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Verona. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Verona. |

- Official website of Verona municipality

- Official website of Pro Loco di Verona

- Outdoor Activities in Verona

.jpg)