Zaha Hadid

| Zaha Hadid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Zaha Mohammad Hadid 31 October 1950 Baghdad, Iraq |

| Died |

31 March 2016 (aged 65) Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | Iraqi-British |

| Alma mater |

American University of Beirut Architectural Association School of Architecture |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Website |

www |

| Practice | Zaha Hadid Architects |

| Buildings | MAXXI, Bridge Pavilion, Maggie's Centre, Contemporary Arts Center |

Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid, DBE (Arabic: زها حديد Zahā Ḥadīd; 31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was an Iraqi-born British architect. She was the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 2004.[1] She received the UK's most prestigious architectural award, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, she was made a Dame by Elizabeth II for services to architecture, and in 2015 she became the first woman to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.[2]

She was dubbed by The Guardian as the 'Queen of the curve'.[3] She liberated architectural geometry[4] with the creation of highly expressive, sweeping fluid forms of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry that evoke the chaos and flux of modern life.[5] A pioneer of parametricism, and an icon of neo-futurism, with a formidable personality, her acclaimed work and ground-breaking forms include the aquatic centre for the London 2012 Olympics, the Broad Art Museum in the U.S., and the Guangzhou Opera House in China.[6] At the time of her death in 2016, Zaha Hadid Architects in London was the fastest growing British architectural firm.[7] Many of her designs are to be released posthumously, ranging in variation from the 2017 Brit Awards statuette to a 2022 FIFA World Cup stadium.[8][9]

Early life

Hadid was born on 31 October 1950 in Baghdad, Iraq, to an upper-class Iraqi family.[10] Her father, Muhammad al-Hajj Husayn Hadid, was a wealthy industrialist from Mosul, Iraq. He co-founded the left-liberal al-Ahali group in Iraq in 1932, which was a significant political organisation in the 1930s and 1940s.[10] He was the co-founder of the National Democratic Party in Iraq.[10] Her mother, Wajiha al-Sabunji, was an artist from Mosul.[11] In the 1960s Hadid attended boarding schools in England and Switzerland.[12][13]

Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving, in 1972, to London to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture.[11] There she met Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis and Bernard Tschumi.[10] She worked for her former professors, Koolhaas and Zenghelis, at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, becoming a partner in 1977.[5] Through her association with Koolhaas, she met Peter Rice, the engineer who gave her support and encouragement early on, at a time when her work seemed difficult.[10] Hadid was a naturalised citizen of the United Kingdom.[14][15]

Career

Hadid established her own London-based architecture practice in 1980.[16] Her international reputation was greatly enhanced in 1988 by a showing of impressive architecture drawings as part of the groundbreaking exhibition "Deconstructivism in Architecture" curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley at New York's Museum of Modern Art.[6]

Teaching

In the mid-1980s, Hadid taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design,[17] where she held the Kenzo Tange Professorship, and at the Architectural Association.[5]

In the 1990s, she held the Sullivan Chair professorship at the University of Illinois at Chicago's School of Architecture. At various times, she served as guest professor at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (HFBK Hamburg), the Knowlton School of Architecture at Ohio State University, the Masters Studio at Columbia University, and was the Eero Saarinen Visiting Professor of Architectural Design at the Yale School of Architecture. From 2000, Hadid was a guest professor at the Institute of Architecture at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, in the Zaha Hadid Master Class Vertical-Studio.[18]

Hadid was named an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and an honorary fellow of the American Institute of Architects. She was on the board of trustees of The Architecture Foundation.[19]

Interior architecture and product design

Hadid also undertook some high-profile interior work, including the Mind Zone at the Millennium Dome in London as well as creating fluid furniture installations within the Georgian surroundings of Home House private members club in Marylebone, and the Z.CAR hydrogen-powered, three-wheeled automobile. In 2009 she worked with the clothing brand Lacoste, to create a new, high fashion, and advanced boot.[20][21] In the same year, she also collaborated with the brassware manufacturer Triflow Concepts to produce two new designs in her signature parametric architectural style.[22]

In 2007, Hadid designed Dune Formations for David Gill Gallery and the Moon System Sofa for leading Italian furniture manufacturer B&B Italia.[23][24]

In 2013, Hadid designed Liquid Glacial for David Gill Gallery which comprises a series of tables resembling ice-formations made from clear and coloured acrylic. Their design embeds surface complexity and refraction within a powerful fluid dynamic.[25] The collection was further extended in 2015-2016. In 2016 the gallery launched Zaha's final collection of furniture entitled UltraStellar [26]

Architectural work

Her architectural design firm, Zaha Hadid Architects, employs 400 people, and is headquartered in a Victorian former school building in Clerkenwell, London.[27]

Conceptual projects

- Cardiff Bay Opera House (1995), Cardiff, Wales – not realised

- Price Tower the extension hybrid project (2002), Bartlesville, Oklahoma, United States – pending

- Signature Towers (2006)

Completed projects (selection)

- Vitra Fire Station (1994), Weil am Rhein, Germany

- Bergisel Ski Jump (2002), Innsbruck, Austria

- Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art (2003), Cincinnati, Ohio, United States

- Hotel Puerta America (2003–2005), Madrid, Spain

- BMW Central Building (2005), Leipzig, Germany

- Ordrupgaard annexe (2005), Copenhagen, Denmark

- Phaeno Science Center (2005), Wolfsburg, Germany

- R. Lopez De Heredia Wine Pavilion (2001–2006), Haro, La Rioja, Spain

- Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut (2006–14), Beirut, Lebanon

- Maggie's Centres at the Victoria Hospital (2006), Kirkcaldy, Scotland

- Hungerburgbahn new stations (2007), Innsbruck, Austria

- Chanel Mobile Art Pavilion (2006–08), worldwide

- Bridge Pavilion (2008), Zaragoza, Spain

- Pierresvives (2002–12), Montpellier, France

- MAXXI – National Museum of the 21st Century Arts (1998–2010), Rome, Italy.[28] Stirling Prize 2010 winner.

- Guangzhou Opera House (2010), Guangzhou, People's Republic of China

- Sheikh Zayed Bridge (2007–10), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- Galaxy SOHO in Beijing, China.[29]

- London Aquatics Centre (2011), 2012 Summer Olympics, London, United Kingdom

- Riverside Museum (2007–11) development of Glasgow Transport Museum, Scotland

- CMA CGM Tower (2004–11), Marseilles, France

- Evelyn Grace Academy (2006–10) in Brixton, London, UK. Stirling Prize 2011 winner.

- Capital Hill Residence, in Moscow, Russia.

- Roca London Gallery (2009–11) in Chelsea Harbour, London, UK

- d'Leedon, Singapore (2011)

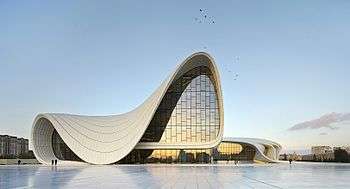

- Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre (2007–12) in Baku, Azerbaijan.[30]

- Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum (2010–12), East Lansing, Michigan, United States[31]

- Mandarin Oriental Dellis Cay, Villa D (2012) (private home under construction), Dellis Cay, Turks & Caicos Islands

- Library and Learning Center of the Vienna University of Economics and Business Campus

- Salerno Maritime Terminal (2007–13), Salerno, Italy

- Napoli Afragola railway station, Italy (2013)[32]

- Jockey Club Innovation Tower (2013), Hong Kong

- Dongdaemun Design Plaza (2008–14), Seoul, South Korea[33]

- Citylife office tower (Storto) and residentials, Milan, Italy (2014)

- Investcorp Building, St Antony's College, Oxford (2013–15), UK.[34]

- King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (2010–15)[35]

- Nanjing International Youth Cultural Centre, China (2016)[36]

Ongoing projects

- 600 Collins Street, Melbourne, Australia[37]

- One Thousand Museum, Miami, United States

- Antwerp Harbour House, Antwerp, Belgium

- Nuragic and Contemporary art museum (on hold), Cagliari, Italy

- Eleftherias Square in Nicosia, Cyprus

- Wangjing SOHO in Beijing, China

- Esfera City Center in Monterrey, Mexico

- New Century City Art Center, Chengdu, China[38]

- 520 West 28th Street, New York City, United States[39]

- Dominion Tower in Moscow, Russia

- Danjiang Bridge in New Taipei, Taiwan

- Iraqi Parliament Building in Baghdad[40]

- 2013 Bottle designed by Zaha Hadid[41]

- 2014 Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup stadium design[42]

- 2016 Mathematics Gallery at the Science Museum London[43]

In 2010, Hadid was commissioned by the Iraqi government to design the new building for the Central Bank of Iraq. An agreement to complete the design stages of the new CBI building was finalized on 2 February 2012, at a ceremony in London.[44] This was her first project in her native Iraq.[45] Other work included Pierres Vives, the new departmental records building (to host three institutions, namely, the archive, the library and the sports department), for French department Hérault, in Montpellier.[46]

Hadid's project was named as the best for the Vilnius Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in 2008. She designed the Innovation Tower for Hong Kong Polytechnic University, scheduled for completion in 2013, and the Chanel Mobile Art Pavilion that was displayed in Hong Kong in 2008.[47][48][49] She completed a new building for Evelyn Grace Academy in London in 2010.[50]

In 2011 the Capital Hill Residence was completed. A villa in the Barvikha Forest outside Moscow, it was designed for Russian property developer Vladislav Doronin and is the only private residence that Hadid designed during her lifetime.[51]

In 2012, Hadid won an international competition to design a new National Olympic Stadium as part of the successful bid by Tokyo to host the 2020 Summer Olympics.[52] As the estimated cost of the construction mounted, however, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced in July 2015 that Hadid's design would be scrapped in favor of a new bidding process to seek a less expensive alternative.[53] Hadid had planned to enter the new competition, but her firm was unable to meet the new requirement of finding a construction company with which to partner.[54]

Non-architectural work

Museum exhibitions

- 1978 – Guggenheim Museum, New York

- 1983 – Retrospective at the Architectural Association, London

- 1985 – GA Gallery, Tokyo

- 1988 – Deconstructivist Architecture show at Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1995 – Graduate School of Design at Harvard University

- 1997 – San Francisco MoMA

- 2000 – British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

- 2001 – Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

- 2002 – (10 May – 11 August) – Centro nazionale per le arti contemporanee, Rome[55]

- 2003 – (4 May – 17 August) – MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna

- 2006 – (3 June – 25 October) – Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- 2006 – (1 June – 29 July) – Ma10 Mx Protetch Gallery, Chelsea, NYC

- 2007 – (29 June – 25 November) – Design Museum, London

- 2007 – Dune Formations with David Gill Gallery – Venice Biennale

- 2011/12 – (20 September – 25 March) – Zaha Hadid: Form in Motion at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

- 2012 – Liquid Glacial – David Gill Gallery, London

- 2013 – (29 June – 29 September) – Zaha Hadid: World Architecture at the Danish Architecture Center[56]

- 2015 – (27 June – 27 September) – Zaha Hadid at the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia[57]

Other work

- Nightlife (1999). Zaha Hadid designed the stage set for the Pet Shop Boys' world tour.

- A Day with Zaha Hadid (2004). A 52-minute documentary where Zaha Hadid discusses her current work while taking the camera through her retrospective exhibition "Zaha Hadid has Arrived". Directed by Michael Blackwood.[58]

- On 2 January 2009, she was the guest editor of the BBC's flagship morning radio news programme, Today.[59]

Death

On 31 March 2016, Hadid died of a heart attack in a Miami hospital, where she was being treated for bronchitis.[60][61]

Reputation

Dubbed 'Queen of the curve', Hadid has a reputation as the world's top female architect,[3][62][63][64][65] although her reputation is not without criticism. She is considered an architect of unconventional thinking, whose buildings are organic, dynamic and sculptural.[66][67] Stanton and others also compliment her on her unique organic designs: "One of the main characteristics of her work is that however clearly recognizable, it can never be pigeonholed into a stylistic signature. Digital knowledge, technology-driven mutations, shapes inspired by the organic and biological world, as well as geometrical interpretation of the landscape are constant elements of her practice. Yet, the multiplicity and variety of the combination among these facets prevent the risk of self-referential solutions and repetitions."[68] Allison Lee Palmer considers Hadid a leader of Deconstructivism in architecture, writing that, "Almost all of Hadid's buildings appear to melt, bend, and curve into a new architectural language that defies description. Her completed buildings span the globe and include the Jockey Club Innovation Tower on the north side of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University in Hong Kong, completed in 2013, that provides Hong Kong an entry into the world stage of cutting-edge architecture by revealing a design that dissolved traditional architecture, the so called modernist “glass box,” into a shattering of windows and melting of walls to form organic structures with halls and stairways that flow through the building, pooling open into rooms and foyers."[69]

Hadid's architectural language has been described by some as "famously extravagant" with many of her projects sponsored by "dictator states".[70] Rowan Moore described Hadid's Heydar Aliyev Center as "not so different from the colossal cultural palaces long beloved of Soviet and similar regimes". Architect Sean Griffiths characterised Hadid's work as "an empty vessel that sucks in whatever ideology might be in proximity to it".[71] Art historian Maike Aden criticises in particular the foreclosure of Zaha Hadid's architecture of the MAXXI in Rome towards the public and the urban life that undermines even the most impressive program to open the museum.[72]

Qatar controversy

As the architect of a stadium to be used for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Hadid defended her involvement in the project, despite revelations relating to the working conditions imposed on migrant workers in Qatar. She acknowledged that there was a serious problem with the number of migrant workers who have died during construction work related to the World Cup. She said that she believed it was a problem for the Qatari government to resolve:

"I have nothing to do with the workers", said Zaha. "I think that's an issue the government—if there's a problem—should pick up. Hopefully, these things will be resolved." Asked if she was concerned, Zaha added: "Yes, but I'm more concerned about the deaths in Iraq as well, so what do I do about that? I'm not taking it lightly but I think it's for the government to look to take care of. It's not my duty as an architect to look at it. I cannot do anything about it because I have no power to do anything about it. I think it's a problem anywhere in the world. But, as I said, I think there are discrepancies all over the world."[73]

In August 2014, Hadid sued The New York Review of Books for defamation for publishing an article which included this quote and allegedly accused her of "showing no concern" for the deaths of workers in Qatar.[74] Immediately thereafter, the reviewer and author of the piece in which she was accused of showing no concern issued a retraction in which he said "...work did not begin on the site for the Al Wakrah stadium, until two months after Ms Hadid made those comments; and construction is not scheduled to begin until 2015.... There have been no worker deaths on the Al Wakrah project and Ms Hadid's comments about Qatar that I quoted in the review had nothing to do with the Al Wakrah site or any of her projects. I regret the error."[9]

Awards, nominations and recognition

In 2002, Hadid won the international design competition to design Singapore's one-north master plan. In 2004, Hadid became the first female and first Iraqi recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.[75] In 2005, her design won the competition for the new city casino of Basel, Switzerland.[76] In 2006, she was honoured with a retrospective spanning her entire work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York; that year she also received an Honorary Degree from the American University of Beirut.

In 2008, she ranked 69th on the Forbes list of "The World's 100 Most Powerful Women".[77] In 2010, she was named by Time as an influential thinker in the 2010 TIME 100 issue.[78]

In September 2010, New Statesman listed Zaha Hadid at number 42 in their annual survey of "The World's 50 Most Influential Figures 2010".[79] Hadid was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2002 and Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2012 Birthday Honours for services to architecture.[80][81]

She was listed as one of the "50 Best-Dressed over 50" by the Guardian in March 2013.[82] Three years later, she was assessed as one of the 100 most powerful women in the UK by Woman's Hour on BBC Radio 4.[83]

She won the Stirling Prize two years running: in 2010, for one of her most celebrated works, the MAXXI in Rome,[84] and in 2011 for the Evelyn Grace Academy, a Z‑shaped school in Brixton, London.[85] She also designed the Dongdaemun Design Plaza & Park in Seoul, South Korea, which was the centerpiece of the festivities for the city's designation as World Design Capital 2010. In 2014, the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, designed by her, won the Design Museum Design of the Year Award, making her the first woman to win the top prize in that competition.[2]

In January 2015, she was nominated for the Services to Science and Engineering award at the British Muslim Awards.[86]

In 2016 in Antwerp, Belgium a square was named after her, Zaha Hadidplein, in front of the extension of the Antwerp Harbour House designed by Zaha Hadid.

Other awards and honours

- 1982: Gold Medal Architectural Design, British Architecture for 59 Eaton Place, London

- 1994: Erich Schelling Architecture Award[87]

- 2001: Equerre d'argent Prize, special mention[88]

- 2002: Austrian State Prize for Architecture for Bergiselschanze

- 2003: European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture for the Strasbourg tramway terminus and car park in Hoenheim, France

- 2003: Commander of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for services to architecture

- 2004: Pritzker Prize

- 2005: Austrian Decoration for Science and Art[89]

- 2005: German Architecture Prize for the central building of the BMW plant in Leipzig

- 2005: Designer of the Year Award for Design Miami

- 2005: RIBA European Award for BMW Central Building[90]

- 2006: RIBA European Award for Phaeno Science Centre[91]

- 2007: Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture

- 2008: RIBA European Award for Nordpark Cable Railway[91]

- 2009: Praemium Imperiale

- 2010: RIBA European Award for MAXXI[92]

- 2012: Jane Drew Prize for her "outstanding contribution to the status of women in architecture"[93]

- 2012: Jury member for the awarding of the Pritzker Prize to Wang Shu in Los Angeles.

- 2013: 41st Winner of the Veuve Clicquot UK Business Woman Award[94]

- 2013: Elected international member, American Philosophical Society[95]

- She was also on the editorial board of the Encyclopædia Britannica.[96]

See also

- Category:Zaha Hadid buildings

- Women in architecture

References

- ↑ Nonie Niesewand (March 2015). "Through the Glass Ceiling". Architectural Digest.

- 1 2 "Dame Zaha Hadid awarded the Riba Gold Medal for architecture". BBC News. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Queen of the curve' Zaha Hadid dies aged 65 from heart attack". The Guardian. 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (31 March 2016). "Zaha Hadid, Groundbreaking Architect, Dies at 65". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- 1 2 3 "Dama Zaha Hadid profile". Design Museum. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- 1 2 Kamin, Blair (1 April 2016). "Visionary architect 1st woman to win Pritzker". Chicago Tribune. 2. p. 7.

- ↑ "The controversial afterlife of Zaha Hadid: from Britain to Baghdad". http://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/architecture/the-controversial-afterlife-of-zaha-hadid-from-britain-to-baghda/. The Telegraph. 28 November 2016. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ "Dame Zaha Hadid's Brit Awards statuette design unveiled". BBC. 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 Joanna Walters. "New York Review of Books critic 'regrets error' in Zaha Hadid article". the Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A warped perspective". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- 1 2 "Zaha Hadid Biography". notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Qureshi, Interview by Huma (14 November 2012). "Zaha Hadid: 'Being an Arab and a woman is a double-edged sword'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Iraqi-British Architect Zaha Hadid Dies of Heart Attack at 65". NDTV.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid biography". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ "Architects: Biography Zaha Hadid". floornature.com. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ "Biography: Zaha Hadid The Pritzker Architecture Prize". www.pritzkerprize.com. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "Harvard Graduate School of Design – Homepage". www.gsd.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "IoA Institute of Architecture". i-o-a.at. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Architecture Foundation Board of Trustees Architecture Foundation". architecturefoundation.org.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Lacoste Shoes – Design – Zaha Hadid Architects". www.zaha-hadid.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Lacoste and Zaha Hadid launch exclusive limited edition footwear collection". www.gizmag.com. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "Triflow Concepts History". triflowconcepts.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "B&B Italia modern contemporary furniture – leading Italian company in the international scene of design furnishings". Bebitalia.it. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Moon System Sofa from B&B Italia". Furniture Fashion. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Liquid Glacial Table – Architecture – Zaha Hadid Architects". www.zaha-hadid.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ http://www.dezeen.com/2016/10/03/ultrastellar-zaha-hadid-architects-patrik-schumacher-wood-leather-furniture-design/

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid Architects". www.zaha-hadid.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Maxxi_Museo Nazionale Delle Arti Del XXI Secolo". Darc.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ "Galaxy Soho – Architecture – Zaha Hadid Architects". Zaha-hadid.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Photo from Reuters Pictures". Reuters Daylife. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Howell, Brandon (13 November 2012). "Broad Art Museum draws thousands to Michigan State during opening weekend; $40 million fundraising goal met". MLive Lansing. East Lansing.

- ↑ "Afragola station delayed" (156). Today's Railways Europe. December 2008: 52.

- ↑

- ↑ Glancey, Jonathan (14 June 2015). "Zaha Hadid's Middle East Centre lands in Oxford". The Sunday Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ Syed, Imran. "King opens petroleum research & study center". Saudi Gazette. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Nanjing International Youth Culture Centre by Zaha Hadid". designboom | architecture & design magazine. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- ↑ Dow, Aisha (2016-07-11). "Green light for Hadid tower seen as global drawcard". The Age. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- ↑ "New Century City Art Centre". Zaha-hadid.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ New York Magazine The Zaha Moment, nymag.com, 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "Iam-Architect.com". Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "first bottle design by zaha hadid: ICON HILL for leo hillinger winery". designboom – architecture & design magazine.

- ↑ "zaha hadid discloses qatar 2022 FIFA world cup stadium design". designboom – architecture & design magazine. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid Science Museum: new mathematics gallery design". designboom | architecture & design magazine. 10 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid Architects and Central Bank of Iraq Sign Agreement for New Headquarters". 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Nayeri, Farah (27 August 2010). "Zaha Hadid to Design New Iraqi Central Bank After June Attack". Bloomberg L.P.

- ↑ "Pierres Vives" (in French). Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ Bonnie Chen In the frame Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. 25 May 2009 The Standard

- ↑ PolyU appoints Zaha Hadid as Architect of Innovation Tower 12 December 2007 Hong Kong Polytechnic University

- ↑ Hadid goes back to Hong Kong Zaha Hadid's Innovation Tower in Hong Kong Friday 14 December 2007 World Architecture News.com

- ↑ Evelyn Grace Academy: Buildings & facilities Archived 1 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "There's Nothing Understated about Vladislav Doronin". Surface. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Chin, Andrea (10 September 2013). "Zaha Hadid: New National Stadium of Japan Venue for Tokyo 2020 Olympics". Designboom. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ Himmer, Alastair (17 July 2015). "Japan rips up 2020 Olympic stadium plans to start anew". news.yahoo.com. AFP. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin (18 September 2015), "Zaha Hadid abandons new 2020 Tokyo Olympics stadium bid", The Guardian, retrieved 27 September 2015

- ↑ "D A R C – Zaha Hadid". Darc.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009. (English) (Italian)

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid – World Architecture". Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Dame Zaha Hadid at the State Hermitage Museum". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Michael Blackwood Productions". Michael Blackwood Productions. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Guest editor: Zaha Hadid". BBC. 27 December 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ "Architect Dame Zaha Hadid dies after heart attack". BBC News. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Editorial Desk (1 April 2016). "'Formidable' Zaha Hadid dies, aged 65". ArchitectureAU. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ Zeiss Stange, Mary; K. Oyster, Carol; E. Sloan, Jane (2013). The Multimedia Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World. SAGE Publications. p. 434. ISBN 9781452270371.

- ↑ Haines-Cooke, Shirley (2009). Frederick Kiesler: Lost in History; Art of This Century and The Modern Art. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9781443808378.

- ↑ McNeill, Donald (2009). The Global Architect: Firms, Fame and Urban Form. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 9781135911638.

- ↑ Prescott, Julie (30 September 2012). The Global Architect: Firms, Fame and Urban Form. IGI Global. p. 51. ISBN 9781466621084.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (2008). Recent Acquisitions, A selection: 2007-2008 - The Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Museum. p. 55.

- ↑ Farrelly, Lorraine (2009). Basics Architecture 02: Construction & Materiality. AVA Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 9782940373833.

- ↑ Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J.; Elliott, Carolyn M. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 271. ISBN 9781452266626.

- ↑ Lee Palmer, Allison (2016). Historical Dictionary of Architecture. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 167–168. ISBN 9781442263093.

- ↑ "On Zaha Hadid, Muammar el-Qaddafi and exploiting the value of big-ticket architecture". Design Observer.

- ↑ Rowan Moore, "Zaha Hadid: queen of the curve". The Observer, 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Maike Aden: Kunst im Belagerungszustand, Urbanophil.net; accessed 1 April 2016. (German)

- ↑ James Riach. "Zaha Hadid defends Qatar World Cup role following migrant worker deaths". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Walters, Joanna (25 August 2014). "Zaha Hadid suing New York Review of Books over Qatar criticism". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Sudjic, Deyan (9 October 2006). "I don't do nice". Jonathan Glancey. London. The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2012."Strictly speaking, she is a Muslim"

- ↑ "Basel rejects Zaha Hadid casino". Dezeen. 25 June 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Edited Mary Ellen Egan and Chana R. Schoenberger (27 August 2008). "The World's 100 Most Powerful Women". Forbes.

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid – The 2010 TIME 100 – TIME". TIME.com. 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "42. Zaha Hadid – 50 People Who Matter 2010". New Statesman. UK. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 60173. p. 6. 16 June 2012.

- ↑ "THE LONDON GAZETTE, SUPPLEMENT No. 1". 16 June 2012. p. 521. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Cartner-Morley, Jess; Mirren, Helen; Huffington, Arianna; Amos, Valerie (28 March 2013). "The 50 best-dressed over 50s". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 – Woman's Hour – The Power List 2013". BBC.

- ↑ Heathcote, Edwin (3 October 2010). "Hadid finally wins Stirling Prize". Financial Times. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Evelyn Grace Academy wins Stirling Prize". BBC News. 2 October 2011.

- ↑ "British Muslim Awards 2015 finalists unveiled". Asian Image. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ↑ "Recipients 1994". Schelling Architekturstiftung. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (in French). Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1713. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ "RIBA Awards". e-architects. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- 1 2 "RIBA European Awards". RIBA. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ "2010: RIBA Award Winners Announced". Bustler. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ Vanessa Quirk (16 April 2012). "Is Zaha's Latest Prize Really an Advancement for Women?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 January 2014. Originally published by ArchDaily 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "Veuve Clicquot Business Woman Award". 22 April 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "Newly Elected – April 2013". Amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Zaha Hadid". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zaha Hadid |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zaha Hadid. |

- Official website

- Zaha Hadid publications at Archello