Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

| Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q82.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 757.31 |

| OMIM | 305100 224900, 129490 |

| DiseasesDB | 29810 |

| GeneReviews | |

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (also known as "Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia," and "Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome"[1]:570) is one of about 150 types of ectodermal dysplasia in humans. Before birth, these disorders result in the abnormal development of structures including the skin, hair, nails, teeth, and sweat glands.[2]:515–517

Presentation

Most people with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia have a reduced ability to sweat (hypohidrosis) because they have fewer sweat glands than normal or their sweat glands do not function properly. Sweating is a major way that the body controls its temperature; as sweat evaporates from the skin, it cools the body. An inability to sweat can lead to a dangerously high body temperature (hyperthermia) particularly in hot weather. In some cases, hyperthermia can cause life-threatening medical problems.

Affected individuals tend to have sparse scalp and body hair (hypotrichosis). The hair is often light-coloured, brittle, and slow-growing. This condition is also characterized by absent teeth (hypodontia) or teeth that are malformed. The teeth that are present are frequently small and pointed.

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is associated with distinctive facial features including a prominent forehead, thick lips, and a flattened bridge of the nose. Additional features of this condition include thin, wrinkled, and dark-colored skin around the eyes; chronic skin problems such as eczema; and a bad-smelling discharge from the nose (ozena).

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is the most common form of ectodermal dysplasia in humans. It is estimated to affect at least 1 in 17,000 people worldwide.

Genetics

Mutations in the EDA, EDAR, and EDARADD genes cause hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. The EDA, EDAR, and EDARADD genes provide instructions for making proteins that work together during embryonic development. These proteins form part of a signaling pathway that is critical for the interaction between two cell layers, the ectoderm and the mesoderm. In the early embryo, these cell layers form the basis for many of the body's organs and tissues. Ectoderm-mesoderm interactions are essential for the formation of several structures that arise from the ectoderm, including the skin, hair, nails, teeth, and sweat glands.

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia has several different inheritance patterns.

EDA (X-linked)

Most cases are caused by mutations in the EDA gene, which are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern, called x-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED). A condition is considered X-linked if the mutated gene that causes the disorder is located on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes. In males (who have only one X chromosome), one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. In females (who have two X chromosomes), a mutation must be present in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder. Males are affected by X-linked recessive disorders much more frequently than females. A striking characteristic of X-linked inheritance is that fathers cannot pass X-linked traits to their sons.

In X-linked recessive inheritance, a female with one altered copy of the gene in each cell is called a carrier. Since females operate on only one of their two X chromosomes (X inactivation) a female carrier may or may not manifest symptoms of the disease. If a female carrier is operating on her normal X she will not show symptoms. If a female is operating on her carrier X she will show symptoms.In about 70 percent of cases, carriers of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia experience some features of the condition. These signs and symptoms are usually mild and include a few missing or abnormal teeth, sparse hair, and some problems with sweat gland function. Some carriers, however, have more severe features of this disorder.

Other than managing symptoms, there is currently no treatment for XLHED. However in December 2012 Edimer Pharmaceuticals a biotechnology company based in Cambridge, MA USA, initiated a Phase I, open-label, safety and pharmacokinetic clinical study of EDI200, a drug aimed at the treatment of XLHED. During development in mice and dogs EDI200 has been shown to substitute for the altered or missing protein resulting from the EDA mutation, which causes XLHED. The initiation of a clinical study of EDI200 in neonates started in October 2013 with the first neonate tested.[3]

EDAR or EDARADD (autosomal)

Less commonly, hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia results from mutations in the EDAR or EDARADD gene. EDAR mutations can have an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, and EDARADD mutations have an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Autosomal dominant inheritance means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. Autosomal recessive inheritance means two copies of the gene in each cell are altered. Most often, the parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the altered gene but do not show signs and symptoms of the disorder.

Notable individuals

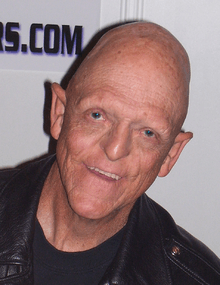

- Michael Berryman, Saturn Award-nominated character actor

Alternate Name

The Eponym, Christ-Siemens-Touraine Syndrome was named after its discoverers, Josef Christ (1871-1948), a German Dentist and Physician from Wiesbaden, who was the First Physician to identify the condition, Hermann Werner Siemens (1891-1969), a Pioneering German Dermatologist from Charlottenburg, who clearly identified its pathological characteristics in the early 1930's and Albert Touraine (1883-1961), a French Dermatologist who likewise noted and identified additional characteristics of the disease in the late 1930's.

See also

- Hermann Werner Siemens

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Albert Touraine

- List of radiographic findings associated with cutaneous conditions

- List of dental abnormalities associated with cutaneous conditions

References

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ "First Baby Dosed in Clinical Trial for XLHED". National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

External links

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia

- Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- Author Web Site for Bonnie J. Rough, whose award-winning memoir "Carrier: Untangling the Danger in My DNA" describes one family's experience with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

- Bonnie J. Rough speaks about her family's history with HED on KRUI's The Lit Show

- Edimer Pharmaceuticals, a biotechnology company based in Cambridge, MA, USA dedicated to developing EDI200 as a potential therapy for X-linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia (XLHED).

- Have the Conversation, a resource website for families affected by X-linked HED.

- The XLHED Network, a website dedicated to connecting the XLHED community.

- Visit ClinicalTrials.gov for a list of clinical trials related to Ectodermal Dysplasia.