Azuchi–Momoyama period

| Azuchi-Momoyama period | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | ||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Late Middle Japanese | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal military confederation | |||||||||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1557–1586 | Ōgimachi | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1586–1611 | Go-Yōzei | ||||||||||||||

| Shogun | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1568–1573 | Ashikaga Yoshiaki | ||||||||||||||

| Head of government | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1568–1582 | Oda Nobunaga | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1583–1598 | Toyotomi Hideyoshi | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1598–1600 | Council of Five Elders | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of Five Elders | |||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Oda Nobunaga captures Kyoto | October 18, 1568 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Ashikaga shogunate abolished | September 2, 1573 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Battle of Nagashino | June 28, 1575 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Assassination of Oda Nobunaga | June 21, 1582 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Toyotomi-Tokugawa alliance formed | 1584 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Defeat of the Hōjō clan | August 4, 1590 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Battle of Sekigahara | October 21, 1600 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Mon | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| a. | Emperor's palace. | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Nobunaga's palatial fortress. | |||||||||||||||

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

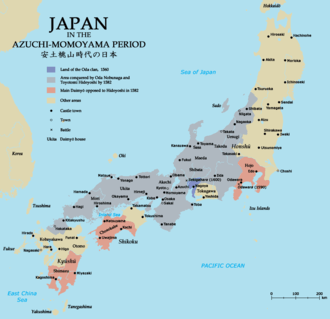

The Azuchi–Momoyama period (安土桃山時代 Azuchi-Momoyama jidai) is the final phase of the Sengoku period (戦国時代 Sengoku jidai) in Japan. These years of political unification led to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. It spans the years from c. 1573 to 1600, during which time Oda Nobunaga and his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, imposed order upon the chaos that had pervaded since the collapse of the Ashikaga shogunate.

Although a start date of 1573 is often given, this period in broader terms begins with Nobunaga's entry into Kyoto in 1568, when he led his army to the imperial capital in order to install Ashikaga Yoshiaki as the 15th – and ultimately final – shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate. The era lasts until the coming to power of Tokugawa Ieyasu after his victory over supporters of the Toyotomi clan at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.[1]

During this period, a short but spectacular epoch, Japanese society and culture underwent the transition from the medieval era to the early modern era.

The name of this period is taken from two castles: Nobunaga's Azuchi Castle (in Azuchi, Shiga) and Hideyoshi's Momoyama Castle (also known as Fushimi Castle, in Kyoto).[1] Shokuhō period (織豊時代 Shokuhō jidai), a term used in some Japanese-only texts, is abridged from the surnames of the period's two leaders (in the on-reading): Shoku (織?) for Oda (織田) plus Hō (豊?) for Toyotomi (豊臣).

Oda Nobunaga

During the last half of the 16th century, a number of different daimyo became strong enough either to manipulate the Ashikaga shogunate to their own advantage or to overthrow it altogether. One attempt to overthrow the bakufu (the Japanese term for the shogunate) was made in 1560 by Imagawa Yoshimoto, whose march towards the capital came to an ignominious end at the hands of Oda Nobunaga in the Battle of Okehazama. In 1562, the Tokugawa clan who was adjacent to the east of Nobunaga's territory became independent of the Imagawa clan, and allied with Nobunaga. The eastern part of the territory of Nobunaga was not invaded by this alliance. Nobunaga then moved his army to the west. In 1565, an alliance of the Matsunaga and Miyoshi clans attempted a coup by assassinating Ashikaga Yoshiteru, the 13th Ashikaga shogun. Internal squabbling, however, prevented them from acting swiftly to legitimatize their claim to power, and it was not until 1568 that they managed to install Yoshiteru's cousin, Ashikaga Yoshihide, as the next Shogun. Failure to enter Kyoto and gain recognition from the imperial court, however, had left the succession in doubt, and a group of bakufu retainers led by Hosokawa Fujitaka negotiated with Nobunaga to gain support for Yoshiteru's younger brother, Yoshiaki.

Nobunaga, who had prepared over a period of years for just such an opportunity by establishing an alliance with the Azai clan in northern Ōmi Province and then conquering the neighboring Mino Province, now marched toward Kyoto. After routing the Rokkaku clan in southern Omi, Nobunaga forced the Matsunaga to capitulate and the Miyoshi to withdraw to Settsu. He then entered the capital, where he successfully gained recognition from the emperor for Yoshiaki, who became the 15th and last Ashikaga shogun.

Nobunaga had no intention, however, of serving the Muromachi bakufu, and instead now turned his attention to tightening his grip on the Kinai region. Resistance in the form of rival daimyo, intransigent Buddhist monks, and hostile merchants was eliminated swiftly and mercilessly, and Nobunaga quickly gained a reputation as a ruthless, unrelenting adversary. In support of his political and military moves, he instituted economic reform, removing barriers to commerce by invalidating traditional monopolies held by shrines and guilds and promoting initiative by instituting free markets known as rakuichi-rakuza.

The newly installed shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki also was extremely wary of his powerful nominal retainer Nobunaga, and immediately began to plot against him by forming a wide alliance of nearly every daimyo that was adjacent to the Oda realm including Oda's close ally and brother in-law Azai Nagamasa and the supremely powerful Takeda Shingen, and monk warriors from the Tendai Buddhists monastic center at Mount Hiei near Kyoto (who became the first major casualty of this war as it was completely destroyed by Nobunaga).

As the Oda army was bogged down by fighting on every corner, Takeda Shingen lead what was by then widely considered the most powerful army in Japan and marched towards the Oda home base of Owari, easily crushing Nobunaga's young ally and future Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in the Battle of Mikatagahara along the way.

However, just as the Takeda army was about to deliver a knock out blow against the Oda - Tokugawa alliance, Takeda Shingen suddenly died of mysterious causes (everything from being shot by a sniper in battle, to ninja assassination, to stomach cancer have been suggested.) Having suddenly lost their leader, the Takeda army quickly retreated back to their home base in Kai Province and Nobunaga was saved from the brink of destruction.

With the death of Takeda Shingen in early 1573, the "Anti-Oda Alliance" that Ashikaga Yoshiaki created quickly crumbled as Nobunaga in quick succession destroyed the alliance of Asakura clan and Azai clans that threatened his northern flank, and soon after expelled the Shogun himself from Kyoto.

Even after Shingen's death, there remained several daimyo powerful enough to resist Nobunaga, but none were situated close enough to Kyoto to pose a threat politically, and it appeared that unification under the Oda banner was a matter of time.

Nobunaga's enemies were not only other Sengoku daimyō but also adherents of a Jōdo Shinshu sect of Buddhism who attended Ikkō-ikki, led by Kennyo. He endured though Nobunaga kept attacking his fortress for ten years. Nobunaga expelled Kennyo in the eleventh year, but, through a riot caused by Kennyo, Nobunaga's territory took the bulk of the damage. This long war was called Ishiyama Hongan-ji War.

To suppress Buddhism, Nobunaga lent support to Christianity. A significant amount of Western Christian culture was introduced to Japan by missionaries from Europe. From this exposure, Japan received new foods, a new drawing method, astronomy, geography, medical science, and new printing techniques.

Nobunaga decided to reduce the power of the Buddhist priests, and gave protection to Christianity. He slaughtered many Buddhist priests and captured their fortified temples.[2]

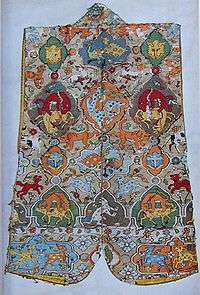

The activities of European traders and Catholic missionaries(Alessandro Valignano, Luís Fróis, Gnecchi-Soldo Organtino and many missionaries) in Japan, no less than Japanese ventures overseas, gave the period a cosmopolitan flavor.[3]

During the period from 1576 to 1579, Nobunaga constructed, on the shore of Lake Biwa at Azuchi, Azuchi Castle, a magnificent seven-story castle that was intended to serve not simply as an impregnable military fortification, but also as a sumptuous residence that would stand as a symbol of unification.

Having secured his grip on the Kinai region, Nobunaga was now powerful enough to assign his generals the task of subjugating the outlying provinces. Shibata Katsuie was given the task of conquering the Uesugi clan in Etchū, Takigawa Kazumasu confronted the Shinano Province that a son of Shingen Takeda Katsuyori governs, and Hashiba Hideyoshi was given the formidable task of facing the Mōri clan in the Chūgoku region of western Honshū.

In 1575, Nobunaga won a significant victory over the Takeda clan in the Battle of Nagashino. Despite the strong reputation of Takeda's samurai cavalry, Oda Nobunaga embraced the relatively new technology of the Arquebus, and inflicted a crushing defeat. The legacy of this battle forced a complete overhaul of traditional Japanese warfare.[4]

In 1582, after a protracted campaign, Hideyoshi requested Nobunaga's help in overcoming tenacious resistance. Nobunaga, making a stop-over in Kyoto on his way west with only a small contingent of guards, was attacked by one of his own disaffected generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, and committed suicide.

Hideyoshi completes the unification

What followed was a scramble by the most powerful of Nobunaga's retainers to avenge their lord's death and thereby establish a dominant position in negotiations over the forthcoming realignment of the Oda clan. The situation became even more urgent when it was learned that Nobunaga's oldest son and heir, Nobutada, had also been killed, leaving the Oda clan with no clear successor.

Quickly negotiating a truce with the Mōri clan before they could learn of Nobunaga's death, Hideyoshi now took his troops on a forced march toward his adversary, whom he defeated at the Battle of Yamazaki less than two weeks later.

Although a commoner who had risen through the ranks from foot soldier, Hideyoshi was now in position to challenge even the most senior of the Oda clan's hereditary retainers, and proposed that Nobutada's infant son, Sanpōshi (who became Oda Hidenobu), be named heir rather than Nobunaga's adult third son, Nobutaka, whose cause had been championed by Shibata Katsuie. Having gained the support of other senior retainers, including Niwa Nagahide and Ikeda Tsuneoki, Sanpōshi was named heir and Hideyoshi appointed co-guardian.

Continued political intrigue, however, eventually led to open confrontation. After defeating Shibata at the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583 and enduring a costly but ultimately advantageous stalemate with Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute in 1584, Hideyoshi managed to settle the question of succession for once and all, to take complete control of Kyoto, and to become the undisputed ruler of the former Oda domains. The Daimyo of Shikoku Chōsokabe clan surrendered to Hideyoshi in July, 1585, and the Daimyo of Kyushu Shimazu clan also surrendered two years later. He was adopted by the Fujiwara family, given the surname Toyotomi, and granted the superlative title Kanpaku, representing civil and military control of all Japan. By the following year, he had secured alliances with three of the nine major daimyo coalitions and carried the war of unification to Shikoku and Kyūshū. In 1590, at the head of an army of 200,000, Hideyoshi defeated the Hōjō clan, his last formidable rival in eastern Honshū in the siege of Odawara. The remaining daimyo soon capitulated, and the military reunification of Japan was complete.

Japan under Hideyoshi

Land survey

With all of Japan now under Hideyoshi's control, a new structure for national government was set up. The country was unified under a single leader, but the day-to-day governance of the people remained decentralized. The basis of power was distribution of territory as measured by rice production, in units of koku. In 1598, a national survey was instituted and assessed the national rice production at 18.5 million koku, 2 million of which was controlled directly by Hideyoshi himself. In contrast, Tokugawa Ieyasu, whom Hideyoshi had transferred to the Kanto region, held 2.5 million koku.

The surveys, carried out by Hideyoshi both before and after he took the title of taikō, have come to be known as the "Taikō surveys" (Taikō kenchi).[note 1]

Control measures

A number of other administrative innovations were instituted to encourage commerce and stabilize society. In order to facilitate transportation, toll booths and other checkpoints along roads were largely eliminated, as were unnecessary military strongholds. Measures that effectively froze class distinctions were instituted, including the requirement that different classes live separately in different areas of a town and a prohibition on the carrying or ownership of weapons by farmers. Hideyoshi ordered the collection of weapons in a great "sword hunt" (katanagari).

Unification

Hideyoshi sought to secure his position by rearranging the holdings of the daimyo to his advantage. In particular, he reassigned the Tokugawa family to the Kanto region, far from the capital, and surrounded their new territory with more trusted vassals. He also adopted a hostage system, in which the wives and heirs of daimyo resided at his castle town in Osaka.

Hideyoshi attempted to provide for an orderly succession by taking the title taikō, or "retired Kanpaku", in 1591, and turned the regency over to his nephew and adopted son Toyotomi Hidetsugu. Only later did he attempt to formalize the balance of power by establishing administrative bodies. These included the Council of Five Elders, who were sworn to keep peace and support the Toyotomi, the five-member Board of House Administrators, who handled routine policy and administrative matters, and the three-member Board of Mediators, who were charged with keeping peace between the first two boards.

Korean campaigns

Hideyoshi's last major ambition was to conquer the Ming dynasty of China. In April 1592, after having been refused safe passage through Korea, Hideyoshi sent an army of 200,000 to invade and pass through Korea by force. During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), the Japanese occupied Seoul by May 1592, and within three months of the invasion, the Japanese reached Pyongyang. King Seonjo of Joseon fled, and two Korean princes were captured by Katō Kiyomasa.[See also 1][See also 2] Seonjo dispatched an emissary to the Ming court, asking urgently for military assistance.[5] The Chinese emperor sent admiral Chen Lin and commander Li Rusong to aid the Koreans. Commander Li pushed the Japanese out of the northern part of the Korean peninsula. The Japanese were forced to withdraw as far as the southern part of the Korean peninsula by January 1593, and counterattacked Li Rusong. This combat reached a stalemate, and Japan and China eventually entered peace talks.[See also 3]

During the peace talks that ensued between 1593 and 1597, Hideyoshi, seeing Japan as an equal of Ming China, demanded a division of Korea, free-trade status, and a Chinese princess as consort for the emperor. The Joseon and Chinese leaders saw no reason to concede to such demands, nor to treat the invaders as equals within the Ming trading system. Japan's requests were thus denied and peace efforts reached an impasse.

A second invasion of Korea began in 1597, but it too resulted in failure as Japanese forces met with better organized Korean defenses and increasing Chinese involvement in the conflict. Upon the death of Hideyoshi in 1598, his designated successor Toyotomi Hideyori was only 5 years old. As such, the domestic political situation in Japan became unstable, making continuation of the war difficult and causing the Japanese to withdraw from Korea.[6] At this stage, most of the remaining Japanese commanders were more concerned about internal battles and the inevitable struggles for the control of the shogunate.[6]

Sekigahara and the end of the Toyotomi rule

Hideyoshi had on his deathbed appointed a group of the most powerful lords in Japan—Tokugawa, Maeda, Ukita, Uesugi, Mōri—to govern as the Council of Five Elders until his infant son, Hideyori, came of age. An uneasy peace lasted until the death of Maeda Toshiie in 1599. Thereafter, Ishida Mitsunari accused Ieyasu of disloyalty to the Toyotomi name, precipitating a crisis that led to the Battle of Sekigahara. Generally regarded as the last major conflict of the Azuchi–Momoyama period and sengoku-jidai, Ieyasu's victory at Sekigahara marked the end of the Toyotomi reign. Three years later, Ieyasu received the title Seii Taishogun, and established the Edo bakufu, which lasted until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Social and cultural developments during the Momoyama period

The Momoyama period was a period of interest in the outside world, which also saw the development of large urban centers and the rise of the merchant class. The ornate castle architecture and interiors adorned with painted screens embellished with gold leaf were a reflection of a daimyo's power but also exhibited a new aesthetic sense that marked a clear departure from the somber monotones favored during the Muromachi period. A specific genre that emerged at this time was called the Namban style—exotic depictions of European priests, traders, and other "southern barbarians."

The art of the tea ceremony also flourished at this time, and both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi lavished time and money on this pastime, collecting tea bowls, caddies, and other implements, sponsoring lavish social events, and patronizing acclaimed masters such as Sen no Rikyū.

Hideyoshi had occupied Nagasaki in 1587, and thereafter sought to take control of international trade and to regulate the trade associations that had contact with the outside world through this port. Although China rebuffed his efforts to secure trade concessions, Hideyoshi's commercial missions successfully called upon present-day Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand in red seal ships. He was also suspicious of Christianity in Japan, which he saw as potentially subversive, and some missionaries were crucified by his regime.

Famous senryū

The contrasting personalities of the three leaders who contributed the most to Japan's final unification—Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu—are encapsulated in a series of three well-known senryū that are still taught to Japanese schoolchildren:

- Nakanunara, koroshiteshimae, hototogisu. (If the cuckoo does not sing, kill it.) 「鳴かぬなら殺してしまえホトトギス」

- Nakanunara, nakasetemiyou, hototogisu. (If the cuckoo does not sing, coax it.) 「鳴かぬなら鳴かせてみようホトトギス」

- Nakanunara, nakumadematou, hototogisu. (If the cuckoo does not sing, wait for it.) 「鳴かぬなら鳴くまでまとうホトトギス」

Nobunaga, known for his ruthlessness, is the subject of the first; Hideyoshi, known for his resourcefulness, is the subject of the second; and Ieyasu, known for his perseverance, is the subject of the third verse.

Chronology

- 1568: Nobunaga enters Kyoto, marking the beginning of the Azuchi–Momoyama period

- 1573: Nobunaga overthrows the Muromachi bakufu and exerts control over central Japan

- 1575: Nobunaga defeats the Takeda clan the Battle of Nagashino

- 1580: The Ikkō-ikki finally surrender their fortress of Ishiyama Honganji to Nobunaga, after enduring an 11-year siege.

- 1582:

- Incident at Honnō-ji, Nobunaga is assassinated by Akechi Mitsuhide, who is then defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi at the Battle of Yamazaki.

- Hideyoshi initiated the Taikō kenchi surveys.

- Tenshō embassy is sent by the Japanese Christian lord Ōtomo Sōrin.

- 1584: Hideyoshi fights Tokugawa Ieyasu to a standstill at the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute.

- 1586: Osaka castle is built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

- 1588: Hideyoshi issues the order of Sword hunt (刀狩 katanagari).

- 1590: Hideyoshi defeats the Hōjō clan, effectively unifying Japan.

- 1591: Sen no Rikyū is forced to commit suicide by Hideyoshi.

- 1592: Hideyoshi initiates the first invasion of Korea.

- 1593: Toyotomi Hideyori is born.

- 1595: Hideyoshi orders his nephew and reigning kampaku, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, to commit seppuku.

- 1597: Second invasion of Korea.

- 1598: Hideyoshi dies.

- 1599: Maeda Toshiie dies.

- 1600: Ieyasu is victorious at the Battle of Sekigahara, marking the end of the Azuchi–Momoyama period.

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ History of Ming : 昖棄王城,令次子琿攝國事,奔平壤。已,複走義州,願內屬。七月,兵部議令駐劄險要,以待天兵;號召通國勤王,以圖恢復。而是時倭已入王京,毀墳墓,劫王子、陪臣,剽府庫,八道幾盡沒,旦暮且渡鴨綠江,請援之使絡繹於道。

- ↑ 北関大捷碑 "其秋清正 入北道、兵鋭甚、鐡嶺以北無城守焉、於是鞠敬仁等叛、應賊、敬仁者會寧府吏也、素志不卒、及賊到富寧、隙危扇亂、執兩王子及宰臣、□播者、並傳諸長吏、與賊效欸"

- ↑ History of Ming : 明年,如松 (Li Rusong)師大捷於平壤,朝鮮所失四道並複。如松乘勝趨碧蹄館,敗而退師。

References

- 1 2 Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (first edition, 1983), section "Azuchi-Momoyama History (1568–1600)" by George Elison, in the entry for "history of Japan".

- ↑ John Whitney Hall, ed. The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan (1991) table of contents

- ↑ All Illustrated Encyclopedia, ed. Japanese History:11 Experts Reflect on the Past (1996), Kodansya International.Inc

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephan R. (1996). The Samurai: a military history. Psychology Press. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-1-873410-38-7.

- ↑ Jinju National Museum: Chronology, June 1592

- 1 2 The Columbia Encyclopedia, sixth edition; 2006 - "Hideyoshi": "In 1592 he attempted to conquer China but succeeded only in occupying part of Korea; just before his death he ordered withdrawal from Korea."

Further reading

- Momoyama, Japanese art in the age of grandeur. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1975. ISBN 9780870991257.

| Preceded by Sengoku period 1467–1573 |

History of Japan Azuchi–Momoyama period 1573–1603 |

Succeeded by Edo period 1603–1868 |

| Preceded by Muromachi period 1337–1573 |