Bahadur Shah II

| Bahadur Shah Zafar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mughal Emperor Emperor of India Badshah | |||||

%2C_last_Mughal_emperor_of_India.jpg) | |||||

| 19th and last Mughal Emperor | |||||

| Reign | 28 September 1837 – 14 September 1857 (20 years 42 days) | ||||

| Coronation | 29 September 1837 at the Red Fort, Delhi, | ||||

| Predecessor | Akbar II | ||||

| Successor |

Empire abolished (Victoria as Empress of India) | ||||

| Born |

24 October 1775 Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died |

7 November 1862 (aged 87) Rangoon (now Yangon), British Burma (now in Myanmar) | ||||

| Burial |

7 November 1862 Rangoon (now Yangon), British Burma (now in Myanmar) | ||||

| Spouse |

Ashraf Mahal Akhtar Mahal Zinat Mahal Taj Mahal | ||||

| Issue |

Mirza Dara Bakht Mirza Jawan Bakht Mirza Shah Abbas 19 more | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Mughal | ||||

| Father | Shah Akbar-Abdullah II | ||||

| Mother | Lal Bai | ||||

| Religion | Islam (Sufism) | ||||

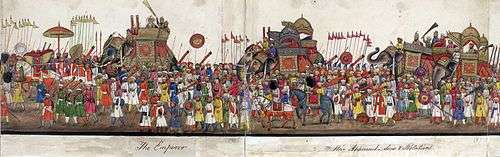

Mirza Abu Zafar Sirajuddin Muhammad Bahadur Shah Zafar was the last Mughal emperor. He was the second son[1] of and became the successor to his father, Akbar II, upon his death on 28 September 1837. He used Zafar, (translation: victory)[2] a part of his name, for his nom de plume (takhallus) as an Urdu poet, and wrote many Urdu ghazals. He was a nominal Emperor, as the Mughal Empire existed in name only and his authority was limited only to the city of Delhi (Shahjahanbad). Following his involvement in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British exiled him to Rangoon in British-controlled Burma, after convicting him on conspiracy charges in a kangaroo court.

Zafar's father, Akbar II had been imprisoned by the British and he was not his father’s preferred choice as his successor. One of Akbar Shah's queens, Mumtaz Begum, pressured him to declare her son as his successor. However, The East India Company exiled Jahangir after he attacked their resident, in the Red Fort.[1]

Reign

Bahadur Shah Zafar presided over a Mughal Empire that only ruled the city Delhi. The Maratha Empire had brought an end to the Mughal Empire in the Deccan in the 18th century and the regions of India under Mughal rule had either been absorbed by the Marathas or declared independence and turned into smaller kingdoms.[3] The Marathas installed Shah Alam II in the throne in 1772, under the protection of the Maratha general Mahadaji Shinde and maintained suzerainty over Mughal affairs in Delhi. The East India Company became the dominant political and military power in mid-nineteenth century India. Outside the region controlled by the Company, hundreds of kingdoms and principalities, fragmented their land. The emperor was respected by the Company and had given him a pension. The emperor permitted the Company to collect taxes from Delhi and maintain a military force in it. Zafar never had any interest in statecraft or had any "imperial ambition". After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British exiled him from Delhi.

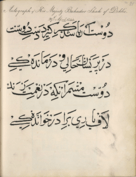

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a noted Urdu poet, having written a number of Urdu ghazals. While some part of his opus was lost or destroyed during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, a large collection did survive, and was compiled into the Kulliyyat-i-Zafar. The court that he maintained was home to several prolific Urdu writers, including Mirza Ghalib, Dagh, Mumin, and Zauq.

After his defeat, he said:[4]

غازیوں میں بو رھےگی جب تک ایمان کیتخت لندن تک چلےگی تیغ ھندوستان کی

As long as there remains the scent of faith in the hearts of our Ghazis, so long shall the Talwar of Hindustan flash before the throne of London

Rebellion of 1857

As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, Sepoy regiments seized Delhi. Because of his neutral views on religions, some Indian kings and regiments accepted Zafar as the Emperor of India.[5]

On 12 May 1857, Zafar held his first formal audience in several years after defeating. It was attended by several sepoys who treated him "familiarly or disrespectfully".[6] When the sepoys first arrived at Bahadur Shah Zafar’s court, he asked them why they had come to him because he had no means of maintaining them. Bahadur Shah Zafar’s conduct was indecisive. However, he yielded to the demands of the sepoys when he was told that they would not be able to win against the East India Company without him.[7]

On 16 May, sepoys and palace servants killed 52 Europeans who were prisoners of the palace and who were discovered hiding in the city. The executions took place under a peepul tree in front of the palace, despite Zafar's protests. The aim of the executioners who were not the supporters of Zafar was to implicate him in the killings.[8] Once he had joined them, Bahadur Shah II took ownership for all the actions of the mutineers. Though Zafar was dismayed by the looting and disorder, he gave his public support to the rebellion. Bahadur Shah Zafar was not directly responsible for the massacre but he could have prevented it, which he did not and thus he was considered a consenting party during his trial.[7]

The administration of the city and its new occupying army was described as "chaotic and troublesome", which functioned "haphazardly". The Emperor nominated his eldest surviving son, Mirza Mughal, as the commander in chief of his forces. However, Mirza Mughal had little military experience and was rejected by the sepoys. The sepoys did not have any commander since each regiment refused to accept orders from someone other than their own officers. Mirza Mughal's administration extended no further than the city. Outside Gujjar herders began levying their own tolls on traffic, and it became increasingly difficult to feed the city.[9]

When the victory of the British became certain, Zafar took refuge at Humayun's Tomb, in an area that was then at the outskirts of Delhi. Company forces led by Major William Hodson surrounded the tomb and Zafar surrendered on 20 September 1857. The next day Hodson shot his sons Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan, and grandson Mirza Abu Bakr under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza near the Delhi Gate.

Many male members of his family were killed by Company forces. Other surviving members of the Mughal dynasty were imprisoned or exiled.

Trial

The trial was a sequence to the Sepoy Mutiny and lasted for 41 days, had 19 hearings, 21 witnesses and over a hundred documents in Persian and Urdu, with their English translations, were produced in the court.[10] At first the trial was suggested to be held at Calcutta, the place where Directors of East India company used to their sittings in connection with their commercial pursuits. But instead, Red Fort in Delhi was selected for the trial.[11] It was the first case to be tried at the Red Fort.[12]

Zafar was tried and found guilty on four counts: -

“1) Aiding and abetting the mutinies of the troops

2) Encouraging and assisting divers persons in waging war against the British Government

3) Assuming the sovereignty of Hindoostan

4) Causing and being accessory to the murder of the Christians.”[13]

On the 20th day of the trial Bahadur Shah II defended himself against these charges.[10] Bahadur Shah in his defence stated his complete haplessness before the will of the sepoys. The sepoys apparently used to affix his seal on empty envelopes, the contents of which he was absolutely unaware. While the emperor may have been overstating his impotence before the sepoys, the fact remains that the sepoys had felt powerful enough to dictate terms to anybody.[14] The eighty-two year old poet-king was harassed by the mutineers and was neither inclined to nor capable of providing any real leadership. Despite this, he was the primary accused in the trial for the rebellion.[12]

Hakim Ahsanullah Khan, Zafar’s most trusted confidant and both his Prime Minister and personal physician, had insisted that Zafar not involve himself in the rebellion and surrender himself to the British. But when Zafar ultimately did this, Hakim Ahsanullah Khan betrayed him by providing evidence against him at the trial in return for a pardon for himself.[15]

Respecting Hodson's guarantee on his surrender, Zafar was not sentenced but exiled to Rangoon, Burma, where he died in November 1862 at the age of 87.[10] His wife Zeenat Mahal and some of the remaining members of the family accompanied him. At 4 AM on 7 October 1858, Zafar along with his wives, two remaining sons began his journey towards Rangoon in bullock carts escorted by 9th Lancers under command of Lieutenant Ommaney.[16]

The occupying forces entered the Red Fort and stole anything that was valuable. Ancient objects, jewels, books and other cultural items were taken which can be found in various museums in Britain. For example, the Crown of Bahadur Shah II is a part of the Royal Collection in London.

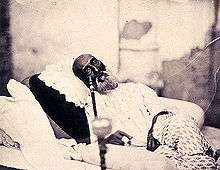

Death

In 1862, at the age of 87, he had reportedly acquired some illness. In October, his condition deteriorated. He was "spoon-fed on broth" but he found that difficult too by 3 November.[17] On 6 November, the British Commissioner H.N. Davies recorded that Zafar "is evidently sinking from pure despitude and paralysis in the region of his throat". To prepare for his death Davies commanded for the collection of lime and bricks and a spot was selected at the "back of Zafar's enclosure" for his burial. Zafar died on Friday, 7 November 1862 at 5 am. Zafar was buried at 4 pm near the Shwe Degon Pagoda at 6 Ziwaka Road, near the intersection with Shwe Degon Pagoda road, Yangon. The shrine of Bahadur Shah Zafar Dargah was built there after recovery of its tomb on 16 February 1991.[18][19] Davies commenting on Zafar, described his life to be "very uncertain".

Family and descendants

Bahadur Shah Zafar had four wives and numerous concubines. His wives were:[20]

- Begum Ashraf Mahal

- Begum Akhtar Mahal

- Begum Zeenat Mahal

- Begum Taj Mahal

He had twenty two sons including:

- Mirza Dara Bakht Miran Shah(1790–1849)

- Mirza Shah Rukh

- Mirza Fath-ul-Mulk Bahadur[21] (alias Mirza Fakhru) (1816–1856)

- Mirza Mughal (1817– 22 September 1857)

- Mirza Khizr Sultan (1834– 22 September 1857)

- Mirza Abu Bakr (1837 to 1857)

- Mirza Jawan Bakht (1841 to 1884)

- Mirza Quaish

- Mirza Shah Abbas (1845–1910)

He had at least thirty-two daughters including:

- Rabeya Begum

- Begum Fatima Sultan

- Kulsum Zamani Begum

- Raunaq Zamani Begum (possibly a granddaughter, died 30 April 1930)

There are believed to be many descendants of Bahadur Shah Zafar living in places of India like Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Delhi, Bhopal, Kolkata, and Bangalore.

His grandchildren were Shazada Jalal Muhammad Mirza and Shazadi All Sakina Banu Begum in Saket Nagar Bhopal. Those two are the sole representatives of his family dynasty.

Zafar Mahal

Zafar Mahal is one of the last remains of Mughal rule is the history of Zafar Mahal in Mehrauli, a locality in Delhi. While Zafar Mahal was built by Akbar II, Bahadur Shah Zafar, constructed its gateway in the mid-nineteenth century. Mehrauli was a known venue for hunting parties, picnics and jaunts away from Delhi, and the dargah was an added attraction. The emperor often visited the place with his retinue and stayed at Zafar Mahal. A plastered dome near the gate was built around the fifteenth century and the other sections were relatively new with influences from Western architecture.

The emperor and his family used to look over the city from the balcony or through its jharokha or windows. During Zafar’s reign, the main Mehrauli-Gurgaon road passed in front of Zafar Mahal, and all passersby were dismounted as a sign of respect for the emperor. When the British refused to comply, Zafar bought the surrounding land and diverted the road so that it would pass away from Zafar Mahal.

The Phool Walon Ki Sair was a three-day celebration during his rule. Zafar would often move his court to a building adjacent to the Shrine of Khwaja Bakhtiyar Kaki and would stay at Mehrauli for a week during the celebrations. The building was originally built by his father and Zafar added a gate and a baaraadari to the structure. Then he renamed it to Zafar Mahal.

The celebrations would spread to different parts of Mehrauli. Jahaz Mahal, a Lodhi period structure became a centre where Qawwali mehfils would be organised. The Jharna, built by Firoz Shah Tughlaq and modified by Akbar Shah II became a place where the women of the court relaxed.

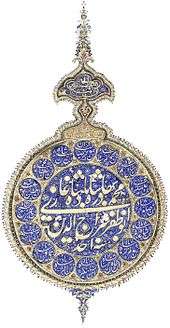

Religious beliefs

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a devout Sufi.[22] He was regarded as a Sufi Pir and used to accept murids or pupils.[22] The newspaper Delhi Urdu Akhbaar described him as "one of the leading saints of the age, approved of by the divine court."[22] Before his accession, he lived like "a poor scholar and dervish", differing from his three royal brothers, Mirza Jahangir, Salim and Babur.[22] In 1828, a decade before he succeeded the throne, Major Archer said that "Zafar is a man of spare figure and stature, plainly apparelled, almost approaching to meanness."[22] His appearance is that of an indigent munshi or teacher of languages".[22]

As a poet, Zafar imbibed the highest subtleties of mystical Sufi teachings.[22] He was also a believer of the magical and superstitious side of the Orthodox Sufism.[22] Like many of his followers, he believed that his position as both a Sufi pir and emperor gave him spiritual powers.[22] In an incident in which one of his followers was bitten by a snake, Zafar tried to cure him by giving a "seal of Bezoar" (a stone antidote to poison) and some water on which he had breathed to the man to drink.[23]

The emperor had a staunch belief in ta'aviz or charms, especially as a palliative for his constant complaint of piles, or to ward off evil spells.[23] During a period of illness, he told a group of Sufi pirs that several of his wives suspected that someone had cast a spell over him.[23] He requested them to take some steps to remove all apprehension on this account. The group wrote some charms and asked the emperor to mix them in water and drink it, which would protect him from the evil. A coterie of pirs, miracle workers and Hindu astrologers were always in touch with the emperor. On their advice, he would sacrifice buffaloes and camels, buried eggs and arrested alleged black magicians, and wore a ring that cured for his indigestion. He also donated cows to the poor, elephants to the Sufi shrines and horses to the khadims or clergy of Jama Masjid.[23]

In one of his verses, Zafar explicitly stated that both Hinduism and Islam shared the same essence.[24] This philosophy was implemented by his court which embodied a multicultural composite Hindu-Islamic Mughal culture.[24]

Epitaph

He was a prolific Urdu poet and calligrapher.[25] He wrote the following Ghazal (Video search) as his own epitaph. In his book, The Last Mughal, William Dalrymple states that, according to Lahore scholar Imran Khan, the beginning of the verse, umr-e-darāz māńg ke ("I asked for a long life") was not written by Zafar, and does not appear in any of the works published during Zafar's lifetime. The verse was allegedly written by Simab Akbarabadi.[26]

| Original Urdu | Devanagari transliteration | Roman transliteration | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

لگتا نہیں ہے جی مِرا اُجڑے دیار میں |

|

|

|

In popular culture

Zafar was portrayed in the play 1857: Ek Safarnama set during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by Javed Siddiqui. It was staged at Purana Qila, Delhi ramparts by Nadira Babbar and the National School of Drama Repertory company in 2008.[29] A Hindi-Urdu black and white movie, Lal Quila (1960), directed by Nanabhai Bhatt, showcased Bahadur Shah Zafar extensively. A television series titled "Bahadurshah Zafar" aired on Doordarshan in 1986. Ashok Kumar played the lead role in it.

See also

References

- 1 2 Husain, S. Mahdi (2006). Bahadur Shah Zafar; And the War of 1857 in Delhi. Aakar Books.

- ↑ "Zafar | meaning of Zafar | name Zafar". Thinkbabynames.com. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers. p. 94.

- ↑ Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar (10 May 1909). The Indian War of Independence – 1857 (PDF).

- ↑ "The Sunday Tribune — Spectrum". Tribuneindia.com. 1907-05-10. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p.212

- 1 2 "Proceedings of the April 1858 Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar 'King of Delhi'". Parliamentary Papers. June 1859.

- ↑ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 223

- ↑ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 145 fn

- 1 2 3 Bhatia, H.S. Justice System and Mutinies in British India. p. 204.

- ↑ Gill, M.S. Trials that Changed History: From Socrates to Saddam Hussein. p. 53.

- 1 2 Sharma, Kanika. A Symbol of State Power: Use of the Red Fort in Indian Political Trials. (PDF). p. 1.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the April 1858 Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar 'King of Delhi'" (PDF). Parliamentary Papers. June 1859.

- ↑ "The Rebel Army in 1857: At the Vanguard of the War of Independence or a Tyranny of Arms?". Economic and Political Weekly. 42.

- ↑ Dalrymple, William (2007). The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi, 1857. Penguin India.

- ↑ Dalrymple, William. The Last Mughal. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143102434.

- ↑ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 473

- ↑ By Amaury Lorin (9 February 2914). "Grave secrets of Yangon's imperial tomb". www.mmtimes.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 474

- ↑ Farooqi, Abdullah. "Bahadur Shah Zafar Ka Afsanae Gam". Farooqi Book Depot. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ↑ "Search the Collections | Victoria and Albert Museum". Images.vam.ac.uk. 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 78

- 1 2 3 4 William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 79

- 1 2 William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 80

- ↑ "Zoomify image: Poem composed by the Emperor Bahadhur Shah and addressed to the Governor General's Agent at Delhi February 1843.". Bl.uk. 2003-11-30. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ "[SASIALIT] bahadur shah zafar poem and its translation attempts". Mailman.rice.edu. 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ "BBC Hindi – भारत". Bbc.co.uk. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ "Jee Nehein Lagta Ujrey Diyaar Mein". http://www.urdupoint.com. Retrieved 21 July 2007. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "A little peek into history". The Hindu. 2 May 2008.

Bibliography

- Portrait of Bahadur Shah in 1840s The Delhi Book of Thomas Metcalfe

- William Dalrymple (2009). The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi, 1857. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-0688-3.

- H L O Garrett (2007). The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Roli Books. ISBN 8174365842.

- K. C. Kanda (2007). Bahadur Shah Zafar and His Contemporaries: Zauq, Ghalib, Momin, Shefta : Selected Poetry. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-3286-5.

- S. Mahdi Husain (2006). Bahadur Shah Zafar; And the War of 1857 in Delhi. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-91-6.

- Shyam Singh Shashi. Encyclopaedia Indica: Bahadur Shah II, The last Mughal Emperor. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- Gopal Das Khosla (1969). The last Mughal. Hind Pocket Books.

- Pramod K. Nayar (2007). The Trial Of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-3270-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bahadur Shah II. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bahadur Shah II.. |

- Bahadur Shah II at the Internet Movie Database

- Extract of talk by Zafar's biographer William Dalrymple (British Library)

- Poetry

- Bahadur Shah Zafar at Kavita Kosh (Hindi)

- Bahadur Shah Zafar Poetry

- Extracts from a book on Bahadur Shah Zafar, with details of exile and family

- Bahadur Shah Zafar Ghazals

- Links to further websites on Bahadur Shah Zafar

- Poetry on urdupoetry.com

- Kalaam e Zafar – Select verses (Hindi)

- Loharu at Roalark.net

- Descendants

- BBC Report on Bahadur Shah's possible descendants in Hyderabad

- An article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Delhi and Hyderabad

- Another article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Hyderabad

- An article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Kolkata

- Forgotten Empress: Sultana Beghum sells tea in Kolkata

| Bahadur Shah II | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Akbar II |

Mughal Emperor 1837–1857 |

Succeeded by Queen Victoria as Empress of India |