Balto-Slavic languages

| Balto-Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, Central Europe, Southeast Europe |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Balto-Slavic |

| Subdivisions: | |

| Glottolog: | balt1263[1] |

|

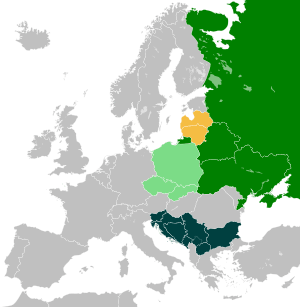

Countries where the national language is:

Eastern Slavic

Western Slavic

Southern Slavic

(Eastern) Baltic | |

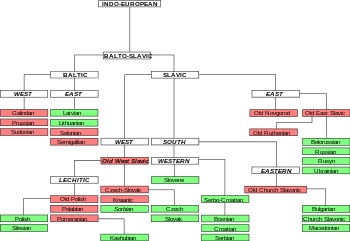

The Balto-Slavic languages are a branch of the Indo-European family of languages. It traditionally comprises the Baltic and Slavic languages. Baltic and Slavic languages share several linguistic traits not found in any other Indo-European branch, which points to a period of common development. Most Indo-Europeanists classify Baltic and Slavic languages into a single branch, even though some details of the nature of their relationship remain in dispute[2] in some circles, usually due to political controversies.[3] Some linguists, however, have recently suggested that Balto-Slavic should be split into three equidistant groups: Eastern Baltic, Western Baltic and Slavic.[4][5]

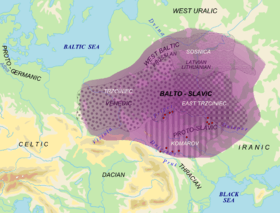

A Proto-Balto-Slavic language is reconstructable by the comparative method, descending from Proto-Indo-European by means of well-defined sound laws, and out of which modern Slavic and Baltic languages descended. One particularly innovative dialect separated from the Balto-Slavic dialect continuum and became ancestral to the Proto-Slavic language, from which all Slavic languages descended.[6]

Historical dispute

The nature of the relationship of the Balto-Slavic languages has been the subject of much discussion from the very beginning of historical Indo-European linguistics as a scientific discipline. A few are more intent on explaining the similarities between the two groups not in terms of a genetic relationship, but by language contact and dialectal closeness in the Proto-Indo-European period.

Baltic and Slavic share many close phonological, lexical, morphosyntactic and accentological similarities (listed below). The notable early Indo-Europeanist August Schleicher (1861) proposed a simple solution: From Proto-Indo-European descended Proto-Balto-Slavic, out of which Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic emerged. The Latvian linguist Jānis Endzelīns thought, however, that any similarities among Baltic and Slavic languages resulted from intensive language contact, i.e. that they were genetically not more closely related and that there was no common Proto-Balto-Slavic language. Antoine Meillet (1905, 1908, 1922, 1925, 1934), the distinguished French Indo-Europeanist, in reaction to a second simplified theory of Schleicher's, propounded a view according to which all similarities of Baltic and Slavic occurred accidentally, by independent parallel development, and that there was no Proto-Balto-Slavic language. In turn, the Polish linguist Rozwadowski suggests that the similarities among Baltic and Slavic languages are a result of not only genetic relationship, but also of later language contact. Thomas Olander corroborates the claim of genetic relationship in his research in the field of comparative Balto-Slavic accentology.[7]

Even though some linguists still reject a genetic relationship, most scholars accept that Baltic and Slavic languages experienced a period of common development. Beekes (1995:22), for example, states expressly that "[t]he Baltic and Slavic languages were originally one language and so form one group".[8] Gray and Atkinson's (2003) application of language-tree divergence analysis supports a genetic relationship between the Baltic and Slavic languages, dating the split of the family to about 1400 BCE. That this was found using a very different methodology than other studies lends some credence to the links between the two.[9]

Modern interpretation

The Balto-Slavic languages are most often divided into Baltic and Slavic groups.[10][11] However, in the 1960s Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov proposed an alternative division, suggesting that the Balto-Slavic proto-language split from the start into West Baltic, East Baltic and Proto-Slavic.[12] With this, Ivanov and Toporov put Baltic unity in question. In their framework, Proto-Slavic is a peripheral and innovative Balto-Slavic dialect that suddenly expanded due to a conjunction of historical circumstances, and effectively erased all the other Balto-Slavic dialects, except in the marginal areas where Lithuanian, Latvian and Old Prussian developed. This model is supported by glottochronologic studies by V. V. Kromer,[13] although both of the most recent computer-generated family trees have a Baltic node parallel to the Slavic node.[14] Onomastic evidence shows that Baltic languages were once spoken in much wider territory than the one they cover today, all the way to Moscow, and were later replaced by Slavic.

Historical expansion

The sudden expansion of Proto-Slavic in the sixth and the seventh century (around AD 600, uniform Proto-Slavic with no detectable dialectal differentiation was spoken from Thessaloniki in Greece to Novgorod in Russia) is according to some connected to the hypothesis that Proto-Slavic was in fact a koiné of the Avar state, i.e. the language of the administration and military rule of the Avar khaganate in Eastern Europe.[15] In 626, the Slavs, Persians and Avars jointly attacked the Byzantine Empire and laid siege to Constantinople. In that campaign the Slavs fought under Avar officers. As of 2009 there was an ongoing controversy over whether the Slavs might then have been a military caste under the khaganate rather than an ethnicity.[16] Their language—at first possibly only one local speech—once koinéized, became a lingua franca of the Avar state. This might explain how Proto-Slavic spread to the Balkans and the areas of the Danube basin,[17] and would also explain why the Avars were assimilated so fast, leaving practically no linguistic traces, and that Proto-Slavic was so unusually uniform. However, such a theory fails to explain how Slavic spread to Eastern Europe, an area that had no historical links with the Avar Khanate.[18]

That sudden expansion of Proto-Slavic erased most of the idioms of the Balto-Slavic dialect continuum, which left us today with only two groups: Baltic and Slavic (or East Baltic, West Baltic, and Slavic in the minority view). This secession of the Balto-Slavic dialect ancestral to Proto-Slavic is estimated on archaeological and glottochronological criteria to have occurred sometime in the period 1500–1000 BCE.[19]

Shared features of the Balto-Slavic languages

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

Religion and mythology

Indian Iranian Other Europe |

The degree of relationship of the Baltic and Slavic languages is indicated by a series of common innovations not shared with other Indo-European languages, and by the relative chronology of these innovations which can be established. The Baltic and Slavic languages also share some inherited words. These are either not found at all in other Indo-European languages (except when borrowed) or are inherited from Proto-Indo-European but have undergone identical changes in meaning when compared to other Indo-European languages.[20] This indicates that the Baltic and Slavic languages share a period of common development, the Proto-Balto-Slavic language.

Common sound changes

- Winter's law: lengthening of vowels before Proto-Indo-European (PIE) unaspirated voiced consonants (*b, *d, *g).

- PIE voiced aspirated consonants (*bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ, *ǵʰ) merge into the voiced consonants (*b, *d, *g, *ǵ). This also occurred in several other Indo-European branches, but as Winter's law was sensitive to the difference between the two types of consonants, the merger must have happened after it and so is a specific Balto-Slavic innovation.

- Hirt's law: retraction of the PIE accent to the preceding syllable, if that syllable ended in a laryngeal (*h₁, *h₂, *h₃, see Laryngeal theory).

- A high vowel is inserted before PIE syllabic sonorants (*l̥, *r̥, *m̥, *n̥). This vowel is usually *i (giving *il, *ir, *im, *in) but in some occasions also *u (*ul, *ur, *um, *un). Proto-Germanic is the only other Indo-European language that inserts a high vowel (*u in all cases), all others insert mid or low vowels instead.

- Emergence of a register distinction on long syllables, between acute (probably glottalized) and circumflex. The acute arose primarily when the syllable ended in a PIE voiced consonant (as in Winter's law) or when it ended in a laryngeal. The distinction is reflected in most Balto-Slavic languages, including Proto-Slavic, as an opposition between rising and falling tone on accented syllables. Some Baltic languages directly reflect the acute register in the form of a so-called "broken tone".

- Shortening of vowels before word-final *m.[21]

- Word-final *-mi > *-m after a long vowel.[21] This followed the preceding change, as the preceding long vowel is retained.

- Raising of stressed *o to *u in a final syllable.[21]

- Merging of PIE short *o and *a into *a or *o. This change also occurred in several other Indo-European branches, but here too it must have happened after Winter's law: Winter's law lengthens *o to *ō and *a to *ā, and must therefore have occurred before the two sounds merged. It also followed the raising of *o to *u above. It is to be noted that both vowels merged differently in both groups: Baltic languages have a in both cases, but Slavic ones have o (compare Lith. ašìs with old. Sl. ось (from Ide. *a: Latin axis, Greec ἄζων); Lith. avìs, old Slavic овьца (from Ide. *ŏ: Latin ovis, Greec ὄις). The Indoeuropean long vowels *ā and *ō merged only in the Slavic group, and later only in old Prussian.[22]

Common Balto-Slavic innovations include several other changes, which are also shared by several other Indo-European branches. These are therefore not direct evidence for the existence of a common Balto-Slavic family, but they do corroborate it.

- Satemization: The PIE palatovelar consonants *ḱ, *ǵ, *ǵʰ become palatal sibilants *ś, *ź, *ź, while the PIE labiovelar consonants *kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰ lose their labalization and merge with the plain velar *k, *g, *gʰ. The palatal sibilants later become plain sibilants *s, *z in all Balto-Slavic languages except Lithuanian.

- Ruki sound law: *s becomes *š when preceded by *r, *u, *k or *i. In Slavic, this *š later becomes *x (variously spelled ⟨ch⟩, ⟨h⟩ or ⟨х⟩ in the Slavic languages) when followed by a back vowel.

Common grammatical innovations

- Replacement of the original PIE genitive singular ending of thematic (o-stem) nouns, which is reconstructed as *-osyo, with the ablative ending *-ād (Proto-Slavic *vьlka, Lithuanian vil̃ko, Latvian vìlka). Old Prussian, however, has another ending, perhaps stemming from the original PIE genitive: deiwas "god's", tawas "father's".

- Use of the ending *-ān (from earlier *-āmi) of the instrumental singular in ā-stem nouns and adjectives.[21] This contrasts with Sanskrit -ayā, archaic Vedic -ā. Lithuanian rankà is ambiguous and could have originated from either ending, but the correspondence with East Lithuanian runku and Latvian rùoku point to Balto-Slavic *-ān.

- Use of the ending *-mis in the instrumental plural, e.g. Lithuanian sūnumìs, Old Church Slavonic synъmi "with sons". This ending is also found in Germanic, while the other Indo-European languages have an ending with -bʰ-, as in Sanskrit -bhis.

- Creation of a distinction between definite (meaning similar to "the") and indefinite adjectives (meaning similar to "a"). The definite forms were formed by attaching the corresponding form of the relative/demonstrative pronoun *jas to the end of the adjective. For example, Lithuanian geràsis 'the good' as opposed to gẽras 'good', Old Church Slavonic dobrъjь 'the good' as opposed to dobrъ 'good'. These forms in Lithuanian, however, seem to have developed after the split, since in older Lithuanian literature (16th century and onwards) they had not yet merged (e. g. naujamę́jame ʽin the new one’ from *naujamén + *jamén). In Lithuanian, the pronoun merged with the adjective having a modern (secondary) pronominal inflection; in Slavic, the pronoun merged with an adjective, having an ancient (primary) nominal inflection.[22]

- Usage of the genitive case for the direct object of a negative verb. For example, Russian кни́ги (я) не читал, Lith. knygos neskaičiau 'I haven't read the book'.[23]

Shared vocabulary

Some examples of words shared among most or all Balto-Slavic languages:

- *léiˀpāˀ 'tilia' (linden tree): Lithuanian líepa, Old Prussian līpa, Latvian liẽpa, Latgalian līpa, Common Slavic *lipa (Old Church Slavonic липа, Russian ли́па, Polish lipa, Czech lípa)

- *ránkāˀ 'hand': Lithuanian rankà, Old Prussian rānkan (acc. sg.), Latvian ròka, Latgalian rūka, Common Slavic *rǭkà (Old Church Slavonic рѫка, Russian рука́, Polish ręka, Czech ruka)

- *galwā́ˀ 'head': Lithuanian galvà, Old Prussian galwo, Latvian galva, Latgalian golva; Common Slavic *golvà (Old Church Slavonic глава, Russian голова́, Polish głowa, Czech hlava)

See also

- List of Balto-Slavic languages

- Corded Ware culture

- International Workshop on Balto-Slavic Accentology

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Balto-Slavic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Balto-Slavic languages. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online". Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

Those scholars who accept the Balto-Slavic hypothesis attribute the large number of close similarities in the vocabulary, grammar, and sound systems of the Baltic and Slavic languages to development from a common ancestral language after the breakup of Proto-Indo-European. Those scholars who reject the hypothesis believe that the similarities are the result of parallel development and of mutual influence during a long period of contact.

- ↑ Fortson (2010:414)

- ↑ Kortlandt, Frederik (2009), Baltica & Balto-Slavica, p. 5,

Though Prussian is undoubtedly closer to the East Baltic languages than to Slavic, the characteristic features of the Baltic languages seem to be either retentions or results of parallel development and cultural interaction. Thus I assume that Balto-Slavic split into three identifiable branches, each of which followed its own course of development.

- ↑ Derksen, Rick (2008), Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, p. 20,

"I am not convinced that it is justified to reconstruct a Proto-Baltic stage. The term Proto-Baltic is used for convenience’s sake.

- ↑ Young (2006)

- ↑ Olander (2002)

- ↑ Beekes & 1995 (22)

- ↑ Gray & Atkinson (2003)

- ↑ James Clackson, Indo-European Linguistics, An Introduction (2007, Cambridge)

- ↑ Benjamin W. Fortson IV, Indo-European Language and Culture, An Introduction (2nd ed, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell)

- ↑ Иванов, В. B. & Toпоров, B. H. 1958, On the Relations between Slavic and Baltic Languages, 4th International Congress of Slavic Studies, Moscow

- ↑ Kromer, Victor V. (2003). "Glottochronology and problems of protolanguage reconstruction". arXiv:cs/0303007

[cs.CL].

[cs.CL]. - ↑ James Clackson, Indo-European Linguistics, An Introduction (2007, Cambridge)--the so-called "Pennsylvania Tree" (pg. 12) and the so-called "New Zealand Tree" (pg. 19)

- ↑ cf. Holzer (2002) with references

- ↑ Controversy discussed in Martin Hurbanič (2009). Posledná vojna antiky. Avarský útok na Konštantínopol roku 626 v historických súvislostiach [The Last War of Antiquity. The Avar Siege of Constantinople, 626, in Historical Sources]. Prešov: Vydavatel’stvo Michala Vaška. pp. 137–153.

- ↑ Until the year 800 Slavic languages were spoken all the way to the Trieste–Hamburg line. Later, they were pushed back to the east.

- ↑ Curta (2004): It is possible that the expansion of the Avar khanate during the second half of the eighth century coincided with the spread of... Slavic into the neighbouring areas of Bohemia, Moravia and southern Poland. (but) could hardly explain the spread of Slavic into Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, all regions that produced so far almost no archaeological evidence of Avar influence

- ↑ cf. Novotná & Blažek (2007) with references. "Classical glottochronology" conducted by Czech Slavist M. Čejka in 1974 dates the Balto-Slavic split to -910±340 BCE, Sergei Starostin in 1994 dates it to 1210 BCE, and "recalibrated glottochronology" conducted by Novotná & Blažek dates it to 1400–1340 BCE. This agrees well with Trzciniec-Komarov culture, localized from Silesia to Central Ukraine and dated to the period 1500–1200 BCE.

- ↑ Mažiulis, Vytautas. "Baltic languages". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Hill, Eugen (2013). "Historical phonology in service of subgrouping. Two laws of final syllables in the common prehistory of Baltic and Slavonic.". Baltistica (XLVIII (2)): 161–204. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- 1 2 Zigmas Zinkevičius. Lietuvių kalbos kilmė [Origin of the Lithuanian Language]. Vilnius, 1984, page 120

- ↑ Matasović (2008:56–57) "Navedimo najvažnije baltoslavenske izoglose...Upotreba genitiva za izricanje objekta zanijekanog glagola"

References

- Barschel; Kozianka; Weber, eds. (1992), Indogermanisch, Baltisch und Slawisch, Kolloquium in Zusammenarbeit mit der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft in Jena, September 1989 (in German), Munich: Otto Sagner, ISBN 3-87690-515-X

- Beekes, Robert (1995), Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, ISBN 90-272-2151-0 (Europe), ISBN 1-55619-505-2 (U.S.)

- Curta, Florin (2004), "The Slavic Lingua Franca. (Linguistic Notes of an Archaeologist Turned Historian)", East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est (31): 125–148

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2010), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2nd ed.), Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-8896-8

- Gray, R.D.; Atkinson, Q.D. (2003), "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin", Nature, 426 (426): 435–439, Bibcode:2003Natur.426..435G, doi:10.1038/nature02029, PMID 14647380

- Holzer, Georg (2001), "Zur Lautgeschichte des baltisch-slavischen Areals", Wiener slavistisches Jahrbuch (in German) (47): 33–50

- Holzer, Georg (2002), "Urslawisch", Enzyklopädie des Europäischen Ostens (PDF) (in German), Klagenfurt: Wieser Verlag, retrieved 2008-10-01

- Holzer, Georg (2007), Historische Grammatik des Kroatischen. Einleitung und Lautgeschichte der Standardsprache (in German), Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, ISBN 978-3-631-56119-5

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1978), "I.-E. palatovelars before resonants in Balto-Slavic" (PDF), Recent Developments in Historical Phonology: 237–243, archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2014

- Kortlandt, Frederik (2009), Baltica & Balto-Slavica, Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, ISBN 978-90-420-2652-0

- Matasović, Ranko (2005), "Toward a relative chronology of the earliest Baltic and Slavic sound changes" (PDF), Baltistica, 40/2, archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2006

- Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika (in Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- Novotná, Petra; Blažek, Václav (2007), "Glottochronolgy and its application to the Balto-Slavic languages" (PDF), Baltistica, XLII (2): 185–210

- Olander, Tomas (2002), Det baltoslaviske problem – Accentologien (pdf) (in Danish) Thomas Olander's master's thesis on the existence of Balto-Slavic genetic node solely on the basis of accentological evidence

- Olander, Thomas (2009), Balto-Slavic Accentual Mobility, Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-020397-4

- Stang, Christian (1957), Slavonic accentuation, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, ISBN 978-82-00-06078-9

- Szemerényi, Oswald (1957), "The problem of Balto-Slav unity", Kratylos, 2: 97–123

- Young, S (2009), "Balto-Slavic languages", Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7

External links

- Balto-Slavic Accentuation, by Kortlandt; a very idiosyncratic approach to Balto-Slavic accentuation

- Трубачев О.; Бернштейн С. (2005), "Отрывки о балто-южнославянских изоглосах", Сравнительная грамматика славянских языков (in Russian), Moscow: Наука (Bernstein and Trubachev on the Balto-South-Slavic isoglosses)

- Biennial International Workshop on Balto-Slavic Natural Language Processing