Proto-Indo-European homeland

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

Religion and mythology

Indian Iranian Other Europe |

The Proto-Indo-European homeland (or Indo-European homeland) is the prehistoric urheimat of the Indo-European languages, the region where their reconstructed common ancestor, the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), was originally spoken. From this region subgroups of speakers migrated and went on to form the proto-communities of the different branches of the language family. The majority of Indo-European specialists support the Kurgan hypothesis,[1] which puts the PIE homeland in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 4000 BC,[2][3] though critical issues remain to be clarified.[4]

The major alternative theory is the Anatolian hypothesis, which puts it in Anatolia around 8000 BC,[5] but has lost support due to the explanatory limitations of this theory.[6][1]

Hypotheses

The Steppe theory and the Anatolian hypothesis are "the two leading competitors" for the Indo-European homeland.[4] The steppe hypothesis, a revised version of the "Kurgan hypothesis", places the PIE homeland in the Pontic steppe around 4000 BC.[3] The majority of Indo-European specialists support the steppe hypothesis,[1] though critical issues remain to be clarified.[4]

The Anatolian hypothesis places the pre-PIE homeland in Anatolia around 8000 BC,[5] and the homeland of Proto-Indo-European proper in the Balkans around 5000 BC. Although it has attracted substantive attention and discussions, the datings it proposes are at odds with the linguistic timeframe for Proto-Indo-European[2] and with genetic data which don't find evidence for Anatolian origins in the Indian genepool.[7]

A notable, though unlikely,[2] third possibility is the "Near Eastern model,"[4] also known as the Armenian hypothesis. It was proposed by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, postulating connections between Indo-European and Caucasian languages based on the disputed glottalic theory and connected to archaeological findings by Grogoriev.[4]

A number of other theories have been proposed, most of which have little or no academic currency today:

- Indigenous Aryans, which suggests a homeland in Indian subcontinent in the 6th millennium BC, which is favored by Hindu nationalists

- a 6th millennium BC or later origin in Northern Europe, according to Lothar Kilian's and, especially, Marek Zvelebil's models of a broader homeland[8]

- Paleolithic Continuity Theory, with an origin in the Upper Paleolithic

- Nikolai Trubetzkoy's theory of Sprachbund origin of Indo-European traits

Theoretical considerations

Traditionally homelands of linguistic families are proposed based on evidence from comparative linguistics coupled with evidence of historical populations and migrations from archeology. Today, genetics via DNA samples is increasingly used in the study of ancient population movements.

Reconstructed vocabulary

Through comparative linguistics it is possible to reconstruct the vocabulary found in the proto-language, and in this way achieve knowledge of the cultural, technological and ecological context that the speakers inhabited. Such a context can then be compared with archeological evidence. This vocabulary includes, in the case of PIE:

- pastoralism, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs[9]

- agriculture and cereal cultivation, including technology commonly ascribed to late-Neolithic farming communities, e.g., the plow[10]

- a climate with winter snow[11]

- transportation by or across water[9]

- the solid wheel[9] used for wagons, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels[12]

Uralic, Caucasian and Semitic borrowings

Proto-Uralic and PIE share a core vocabulary, such as words for "name" and "water," and similar-looking pronouns. This may be due to a common ancestor, or to intensive borrowing, but both options suggest that their homelands were located near each other. PIE also borrowed words from Caucasian languages, especially Kartvelian, which suggests a location close to the Caucasus.

Gramkelidze and Ivanov, using the now largely unsupported glottalic theory of Indo-European phonology, also proposed Semitic borrowings into Proto-Indo-European, suggesting a more southern homeland to explain these borrowings. According to Mallory and Adams, some of these borrowing may be too speculative or from a later date, but they consider the proposed semitic loans "bull" (taurus) and "wine" to be more likely.[12][note 1]

Genesis of Indo-European languages

Phases of Proto-Indo-European

According to Anthony, the following terminology may be used:[2]

- Early PIE for "the last common ancestor of the Anatolian and non-Anatolian IE branches";

- Post-Anatolian PIE for "the last common ancestor of the non-Anatolian PIE languages, including Tocharian";

- Late PIE for "the common ancestor of all other IE branches."

The Anatolian languages are the first Indo-European language family to have split off from the main group. Due to the archaic elements preserved in the Anatolian languages, they may be a "cousin" of Proto-Indo-European, instead of a "daughter," but Anatolian is generally regarded as an early offshoot of the Indo-European language group.[2]

The Indo-Hittite hypothesis postulates a common predecessor for both the Anatolian languages and the other indo-European languages, called Indi-Hittite or Indo-Anatolian.[2] Although it's obvious that PIE had predecessors,[13] the Indo-Hittite hypothesis is not widely accepted, and there is little to suggest that it is possible to reconstruct a proto-Indo-Hittite stage that differs substantially from what is already reconstructed for PIE.

Dating the split-offs of the main branches

Using a mathematical analysis borrowed from evolutionary biology, Don Ringe and Tandy Warnow propose the following tree of Indo-European branches:[2]

- Pre-Anatolian (before 3500 BC)

- Pre-Tocharian

- Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic (before 2500 BC)

- Pre-Armenian and Pre-Greek (after 2500 BC)

- Pre-Germanic and Pre-Balto-Slavic;[2] proto-Germanic c. 500 BC[14]

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2000 BC)

David Anthony, following the methodology of Ringe and Warnow, proposes the following sequence:[2]

- Pre-Anatolian (4200 BC)

- Pre-Tocharian (3700 BC)

- Pre-Germanic (3300 BC)

- Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic (3000 BC)

- Pre-Armenian (2800 BC)

- Pre-Balto-Slavic (2800 BC)

- Pre-Greek (2500 BC)

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2200 BC); split between Iranian and Old Indic 1800 BC

Steppe hypothesis

Gimbutas' Kurgan hypothesis

In the 1970s, a mainstream consensus had emerged among Indo-Europeanists in favour of the "Kurgan hypothesis" (the Kurgan hypothesis, after the kurgans, burial mounds, of the Eurasian steppes) placing the Indo-European homeland in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of the Chalcolithic. This was not least due to the influence of the Journal of Indo-European Studies, edited by J. P. Mallory, that focused on the ideas of Marija Gimbutas and offered some improvements.

Gimbutas had created a modern variation on the traditional invasion theory in which the Indo-Europeans were a nomadic tribe in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia and expanded on horseback in several waves during the 3rd millennium BCE. Their expansion coincided with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see Corded Ware culture), they subjugated the peaceful European Neolithic farmers of Gimbutas' Old Europe. As Gimbutas' beliefs evolved, she put increasing emphasis on the patriarchal, patrilineal nature of the invading culture, sharply contrasting it with the supposedly egalitarian, if not matrilineal culture of the invaded, to the point of formulating essentially a feminist archaeology. Her interpretation of Indo-European culture found genetic support in remains from the Neolithic culture of Scandinavia, where DNA from bone remains in Neolithic graves indicated that the megalith culture was either matrilocal or matrilineal, as the people buried in the same grave were related through the women. Likewise, there is a tradition of remaining matrilineal traditions among the Picts.

Archeology

The Gimbutas-Mallory Kurgan hypothesis seeks to identify the source of the Indo-European language expansion as a succession of migrations from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, originating in the area encompassed by the Sredny Stog culture (ca. 4500 BCE).[15] J. P. Mallory, dating the migrations later, to around 4000 BCE, and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, essentially modified Gimbutas' theory making it compatible with a less gender-political narrative. David Anthony, focusing mostly on the evidence for the domestication of horses and the presence of wheeled vehicles, came to regard specifically the Yamna culture, which replaced the Sredny Stog culture around 3500 BCE, as the most likely candidate for the Proto-Indo-European speech community.[2]

Anthony describes the spread of cattle-raising from early farmers in the Danube Valley into the Ukrainian steppes in the 6th-5th millennium BCE, forming a cultural border with the hunter-gatherers[2] whose languages may have included archaic PIE.[2] Anthony notes that domesticated cattle and sheep probably didn't enter the steppes from the Transcaucasia, since the early farming communities there were not widespread, and separated from the steppes by the glaciated Caucasus.[2] Subsequent cultures developed in this area which adopted cattle, most notably the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.[2]

Parpola regards the Tripolye culture as the birthplace of wheeled vehicles, and therefore as the homeland for Late PIE, assuming that Early PIE was spoken by Skelya pastoralists (early Sredny Stog culture[2] who took over the Tripolye culture at ca. 4300-4000 BCE.[16] On its eastern border lay the Sredny Stog culture (4400-3400 BCE),[2] whose origins are related to "people from the east, perhaps from the Volga steppes."[2] It plays a central role in Gimbutas Kurgan hypothesis,[2] and coincides with the spread of early PIE across the steppes[2] and into the Danube valley (ca. 4000 BCE),[2] leading to the collapse of Old Europe.[2] Here-after the Maykop culture suddenly arose, Tripolye towns grew strongly, and eastern steppe people migrated to the Altai mountains, founding the Afanasevo culture (3300 to 2500 BCE).[2]

Vocabulary

The core element of the steppe hypothesis is the identification of the proto-Indo-European culture as a nomadic pastoralist society, that did not practice intensive agriculture. This identification rests on the fact that vocabulary related to cows, and to horses and horsemanship and wheeled vehicles can be reconstructed for all branches of the family, whereas only a few agricultural vocabulary items are reconstructable, suggesting a gradual adoption of agriculture through contact with non-Indo-Europeans. When this evidence and reasoning is accepted, the search for the Indo-European proto-culture has to involve searching for the earliest introduction of domesticated horses and wagons into Europe.[17]

Responding to these arguments, proponents of the Anatolian hypothesis Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson have argued that the different branches could have independently developed similar vocabulary based on the same roots, creating the false appearance of shared inheritance - or alternatively, that the words related to wheeled vehicle might have been borrowed across Europe at a later date. Proponents of the Steppe hypothesis have argued this to be highly unlikely, and to break with the established principles for reasonable assumptions when explaining linguistic comparative data.[17]

Another source of evidence for the steppe hypothesis is the presence of what appears to be many shared loanwords between Uralic languages and proto-Indo-European, suggesting that these languages were spoken in adjacent areas. This would have had to take place a good deal further north than the Anatolian or Near Eastern scenarios would allow.[17] According to Kortlandt, Indo-Uralic is the pre-PIE, postulating that Indo-European and Uralic share a common ancestor.[18] According to Kortlandt, "Indo-European is a branch of Indo-Uralic which was radically transformed under the influence of a North Caucasian substratum when its speakers moved from the area north of the Caspian Sea to the area north of the Black Sea."[18][note 2][note 3] Anthony notes that the validity of such deep relationships cannot be reliably demonstrated due to the time-depth involved, and also notes that the similarities may be explained by borrowings from PIE into proto-Uralic.[13] Yet, Anthony also notes that the North Caucasian communities "were southern participants in the steppe world."[2]

Genetics

According to genetic studies, individuals from the Yamnaya culture have a mix from eastern European hunter-gatherer[3] and Caucasus hunter-gatherer[23] ancestry. Iran Chalcolithic people with a Caucasian hunter-gatherer component.[24][24][note 4]

Many geneticists consider Haplogroup R1a to be associated with the origins and spread of the Indo-Europeans.[25][26][27] R1a1 shows a strong correlation with the distribution of the Indo-European languages in Europe and south Asia, being most prevalent in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, but also observed in Pakistan, India and central Asia.[26][27] Two specific subclades dominate, namely R1-Z282 in Eastern-Europe, and R1-Z93 which is found in south-Siberia and northern India.[26][27] According to Underhill et al. (2014), the initial diversification of R1a took place in the vicinity of Iran,[28] while Pamjav et al. (2012) think that R1a diversified within the Eurasian Steppes or the Middle East and Caucasus region.[29]

In 2015, a large-scale ancient DNA study published in Nature[30] found evidence of a "massive migration" from the Pontic-Caspian steppe to Central Europe that took place about 4,500 years ago. It found that individuals from the Central European Corded Ware culture (3rd millennium BCE) were genetically closely related to individuals from the Yamnaya culture. The authors concluded that this was evidence for a steppe origin of the Indo-European languages.[31] However, archaeologists have argued that although such a migration might have taken place, it does not necessarily explain either the distribution of archaeological cultures or the spread of the Indo-European languages.[32]

Anatolian hypothesis

Theory

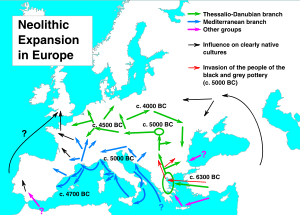

The main competitor to the Kurgan hypothesis is the Anatolian hypothesis advanced by Colin Renfrew in 1987. It couples the spread of the Indo-European languages to the hard fact of the neolithic spread of farming from the Near East, stating that the Indo-European languages began to spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BCE with the Neolithic advance of farming (wave of advance). The expansion of agriculture from the Middle East would have diffused three language families: Indo-European toward Europe, Dravidian toward Pakistan and India, and Afro-Asiatic toward Arabia and North Africa.

According to Renfrew (2004), the spread of Indo-European proceeded in the following steps:

- Around 6500 BC: Pre-Proto-Indo-European, located in Anatolia, splits into Anatolian and Archaic Proto-Indo-European, the language of those Pre-Proto-Indo-European farmers who migrate to Europe in the initial farming dispersal. Archaic Proto-Indo-European languages occur in the Balkans (Starčevo-Körös-Cris culture), in the Danube valley (Linear Pottery culture), and possibly in the Bug-Dniestr area (Eastern Linear pottery culture).

- Around 5000 BC: Archaic Proto-Indo-European splits into Northwestern Indo-European (the ancestor of Italic, Celtic, and Germanic), located in the Danube valley, Balkan Proto-Indo-European (corresponding to Gimbutas' Old European culture), and Early Steppe Proto-Indo-European (the ancestor of Tocharian).

Reacting to criticism, Renfrew revised his proposal to the effect of taking a pronounced Indo-Hittite position. Renfrew's revised views place only Pre-Proto-Indo-European in 7th millennium BC Anatolia, proposing as the homeland of Proto-Indo-European proper the Balkans around 5000 BC, explicitly identified as the "Old European culture" proposed by Marija Gimbutas. He thus still situates the original source of the Indo-European language family in Anatolia around 7000 BC. Reconstructions of a Bronze Age PIE society based on vocabulary items like "wheel" do not necessarily hold for the Anatolian branch, which appears to have separated from PIE at an early stage, prior to the invention of wheeled vehicles.[33]

Objections

Dating

The main objection to this theory is that it requires an unrealistically early date.[17] According to linguistic analysis, the Proto-Indo-European lexicon seems to include words for a range of inventions and practices related to the Secondary Products Revolution, which post-dates the early spread of farming. On lexico-cultural dating, Proto-Indo-European cannot be earlier than 4000 BC.[34]

Farming

The idea that farming was spread from Anatolia in a single wave has been revised. Instead it appears to have spread in several waves by several routes, primarily from the Levant.[35] The trail of plant domesticates indicates an initial foray from the Levant by sea.[36] The overland route via Anatolia seems to have been most significant in spreading farming into south-east Europe.[37]

Farming developed independently in the eastern fertile crescent.[7] Non-Indo-European languages appear to be associated with the spread of farming from the Near East into North Africa and the Caucasus. According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), farming developed independently both in the Levant and in the eastern Fertile Crescent.[7] After this initial development, the two regions and the Caucasus interacted, and the chalcolithic north-west Iranian population appears to be a mixture of Iranian neolithic, Levant, and Caucasus hunter-gatherers.[7] According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), "farmers related to those from Iran spread northward into the Eurasian steppe; and people related to both the early farmers of Iran and to the pastoralists of the Eurasian steppe spread eastward into South Asia."[38] They further note that ANI "can be modelled as a mix of ancestry related to both early farmers of western Iran and to people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe,"[38] which makes it unlikely that the Indo-European languages in India are derived from Anatolia.[39] Mascarenhas et al. (2015) note that the expansion of Z93 from Transcaucasia into South Asia is compatible with "the archeological records of eastward expansion of West Asian populations in the 4th millennium BCE culminating in the socalled Kura-Araxes migrations in the post-Uruk IV period."[40]

Alignment with Steppe-theory

According to Alberto Piazza "[i]t is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey."[41] According to Piazza and Cavalli-Sforza, the Yamna-culture may have been derived from Middle Eastern Neolithic framers who migrated to the Pontic steppe and developed pastoral nomadism.:

...if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavorable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.[42]

Wells agrees with Cavalli-Sforza that there is "some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East":

... while we see substantial genetic and archaeological evidence for an Indo-European migration originating in the southern Russian steppes, there is little evidence for a similarly massive Indo-European migration from the Middle East to Europe. One possibility is that, as a much earlier migration (8,000 years old, as opposed to 4,000), the genetic signals carried by Indo-European-speaking farmers may simply have dispersed over the years. There is clearly some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East, as Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues showed, but the signal is not strong enough for us to trace the distribution of Neolithic languages throughout the entirety of Indo-European-speaking Europe.[43]

Armenian hypothesis

Gamkrelidze and Ivanov held that the Urheimat was south of the Caucasus, specifically, "within eastern Anatolia, the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia" in the fifth to fourth millennia BC.[44] Their proposal was based on a disputed theory of glottal consonants in PIE. According to Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, PIE words for material culture objects imply contact with more advanced peoples to the south, the existence of Semitic loan-words in PIE, Kartvelian (Georgian) borrowings from PIE, some contact with Sumerian, Elamite and others. However given that the glottalic theory never caught on, and there was little archeological support the Gamkredlize and Ivanov theory did not gain support, until Renfrew's anatolian theory revived aspects of their proposal.[17]

Gamkredilze and Ivanov proposed that the Greeks moving west across Anatolia to their present location, a northward movement of some IE speakers that brought them into contact with the Finno-Ugric languages and suggest that the kurgan area, or better "Black Sea and Volga steppe" was a secondary homeland from which the western IE languages emerged.

A 2015 genetic study by Haak et al. (2015:137) argues that their findings of gene flow of a population that shares traits with modern-day Armenians into the Yamnaya pastoralist culture lends support to the Armenian hypothesis, while Lazaridis et al. (2016) state that "farmers related to those from Iran spread northward into the Eurasian steppe."[7]

Other models

Baltic homeland

Lothar Kilian and Marek Zvelebil have proposed a 6th millennium BCE or later origin in Northern Europe.[8] The Steppe theory is compatible with the argument that the PIE homeland must have been larger,[15] because the "Neolithic creolisation hypothesis" allows the Pontic-Caspian region to have been part of PIE territory.

Palaeolithic Continuity Theory

The "Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm" is a hypothesis suggesting that the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) can be traced back to the Upper Paleolithic, several millennia earlier than the Chalcolithic or at the most Neolithic estimates in other scenarios of Proto-Indo-European origins. Its main proponents are Marcel Otte, Alexander Häusler,[2] and Mario Alinei.

The PCT posits that the advent of Indo-European languages should be linked to the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe and Asia from Africa in the Upper Paleolithic.[45] Employing "lexical periodization", Alinei arrives at a timeline deeper than even that of Colin Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis.[45][note 5]

Since 2004, an informal workgroup of scholars who support the Paleolithic Continuity hypothesis has been held online.[46] Apart from Alinei himself, its leading members (referred to as "Scientific Committee" in the website) are linguists Xaverio Ballester (University of Valencia) and Francesco Benozzo (University of Bologna). Also included are prehistorian Marcel Otte (Université de Liège) and anthropologist Henry Harpending (University of Utah).[45]

It is not listed by Mallory among the proposals for the origins of the Indo-European languages that are widely discussed and considered credible within academia.[47]

Out of India theory

The Indigenous Aryans theory, also known as the Out of India theory, proposes an Indian origin for the Indo-European languages. The languages of northern India and Pakistan, including Hindi and the historically and culturally significant liturgical language Sanskrit, belong to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family.[48] The Steppe model, rhetorically presented as an "Aryan invasion," has been opposed by Hindu revivalists and Hindu nationalists,[49][50] who argue that the Aryans were indigenous to India, and some, such as Koenraad Elst[51][52] and Shrikant Talageri,[53] have proposed that Proto-Indo-European itself originated in northern India, either with or shortly before the Indus Valley Civilisation.[50][54] This "Out of India" theory is not regarded as plausible in mainstream scholarship.[54][55][56]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Anthony notes that those semitic borrowings may also have occurred through the advancement of Anatolian farmer cultures via the Danube valley into the steppe zone.[2]

- ↑ Kortlandt (2010) refers to Kortlandt, Frederik. 2007b. C.C. Uhlenbeck on Indo-European, Uralic and Caucasian.

- ↑ The "Sogdiana hypothesis" of Johanna Nichols places the homeland in the 4th or 5th millennium BCE to the east of the Caspian Sea, in the area of ancient Bactria-Sogdiana.[19][20] According to Bernard Sergent the lithic assemblage of the first Kurgan culture in Ukraine (Sredni Stog II), which originated from the Volga and South Urals, recalls that of the Mesolithic-Neolithic sites to the east of the Caspian sea, Dam Dam Chesme II and the cave of Djebel.[21] He places the roots of the Gimbutas' Kurgan cradle of Indo-Europeans in a more southern cradle, and adds that the Djebel material is related to a Paleolithic material of Northwestern Iran, the Zarzian culture, dated 10,000–8,500 BC, and in the more ancient Kebarian of the Near East. He concludes that more than 10,000 years ago the Indo-Europeans were a small people grammatically, phonetically and lexically close to Semitic-Hamitic populations of the Near East.[22]

- ↑ Lazaridis et al. (2016): "The spread of Near Eastern ancestry into the Eurasian steppe was previously inferred without access to ancient samples, by hypothesizing a population related to present-day Armenians as a source."[24] Lazaridis et al. (2016) refer to haak et al. (2015).

- ↑ Mario Alinei: "The sharp, and now at last admitted even by traditionalists (Villar 1991) [Villar, Francisco (1991), Los indoeuropeos y los orígines de Europa. Lenguaje y historia, Madrid, Gredos] differentiation of farming terminology in the different IE languages, while absolutely unexplainable in the context of Renfrew’s NDT, provides yet another fundamental proof that the differentiation of IE languages goes back to remote prehistory."[45]

References

- 1 2 3 Anthony & Ringe 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Anthony 2007.

- 1 2 3 Haak 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallory 2013.

- 1 2 Gray & Atkinson 2003.

- ↑ Bouckaert et al. 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lazaridis 2016.

- 1 2 Zvelebil 1995.

- 1 2 3 Watkins 2000.

- ↑ Mallory 1996, p. 347.

- ↑ "The Indo-Europeans knew snow in their homeland; the word sneigwh- is nearly ubiquitous." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000 at the Wayback Machine (archived 1 March 2009)

- 1 2 Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 249.

- 1 2 Anthony & Ridge 2015.

- ↑ Ringe 2006, p. 67.

- 1 2 Mallory 1989, p.185

- ↑ Parpola 2015, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anthony, D. W., & Ringe, D. (2015). The Indo-European homeland from linguistic and archaeological perspectives. Annu. Rev. Linguist., 1(1), 199-219.

- 1 2 Kortlandt 2010.

- ↑ Johanna Nichols (1997), "The Epicenter of the Indo-European Linguistic Spread", Archaeology and Language I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations, ed. Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, London: Routledge

- ↑ Johanna Nichols (1999), "The Eurasian Spread Zone and the Indo-European Dispersal", Archaeology and Language II: Correlating archaeological and Linguistic Hypotheses, ed. Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, London: Routledge

- ↑ See Dzhebel, and V. A. Ranov and R. S. Davis (1979), Toward a New Outline of the Soviet Central Asian Paleolithic

- ↑ Bernard Sergent (1995), Les Indo-Européens - Histoire, langues, mythes

- ↑ Jones 2015.

- 1 2 3 Lazaridis 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Zerjal 1999.

- 1 2 3 Panjav 2012.

- 1 2 3 Underhill 2015.

- ↑ Underhill 2014.

- ↑ Pamjav 2012.

- ↑ Haak et al. 2015.

- ↑ Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (4 March 2015) Genetic study revives debate on origin and expansion of Indo-European languages in Europe Science Daily, Retrieved 19 April 2015

- ↑ Linden, Marc Vander (2016-08-03). "Population history in third-millennium-BC Europe: assessing the contribution of genetics". World Archaeology: 1–15. doi:10.1080/00438243.2016.1209124.

- ↑ Renfrew, Colin (2003). "Time Depth, Convergence Theory, and Innovation in Proto-Indo-European: 'Old Europe' as a PIE Linguistic Area". In Bammesberger, Alfred; Vennemann, Theo. Languages in Prehistoric Europe. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter GmBH. pp. 17–48. ISBN 978-3-82-531449-1.

- ↑ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 101-102.

- ↑ R. Pinhasi, J. Fort and A. J. Ammerman, Tracing the origin and spread of agriculture in Europe, PLoS Biology, 3, no. 12 (2005), e436.

- ↑ F. Coward et al., The spread of Neolithic plant economies from the Near East to Northwest Europe: a phylogenetic analysis, Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 35, no. 1 (2008), pp. 42-56.

- ↑ M. Özdogan, Archaeological evidence on the westward expansion of farming communities from eastern Anatolia to the Aegean and the Balkans, Current Anthropology, vol. 52, no. S4 (2011), S415-S430.

- 1 2 Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ↑ Lazaridis 2016b.

- ↑ Mascarenhas 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza 2000.

- ↑ Piazza and Cavalli-Sforza (2006)

- ↑ Wells 2002.

- ↑ T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov, Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans, 1995, Chapters Eleven and Twelve

- 1 2 3 4 Alinei, Mario. The Paleolithic Continuity Theory on Indo-European Origins: An Introduction

- ↑ continuitas.org, The PCP-workgroup

- ↑ Mallory 1997, p. 106.

- ↑ "Indo-Aryan languages". Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ↑ Fosse, Lars Martin (2005), "ARYAN PAST AND POST-COLONIAL PRESENT. The polemics and politics of indigenous Aryanism", in Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L., The Indo-Aryan Controversy. Evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge

- 1 2 Witzel, Michael (2005), "Indocentrism", in Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L., The Indo-Aryan Controversy. Evidence and inference in Indian history (PDF), Routledge

- ↑ Elst, Koenraad (1999), Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, ISBN 81-86471-77-4

- ↑ Elst, Koenraad (2005), "LINGUISTIC ASPECTS OF THE ARYAN NON-INVASION THEORY", in Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L., THE INDO-ARYAN CONTROVERSY. Evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge

- ↑ Talageri, Shrikant G. (2000). The Rigveda : a historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-010-0.

- 1 2 Witzel, Michael (2006), "Rama's realm: Indocentric rewritings of early South Asian History", in Fagan, Garrett, Archaeological Fantasies: How pseudoarchaeology misrepresents the past and misleads the public, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30592-6

- ↑ Shaffer, Jim (1984), The Indo-Aryan Invasions: Cultural Myth and Archaeological Reality. In: "In The Peoples of South Asia", edited by J. R. Lukacs, pp. 74—90, New York: Plenum Press

- ↑ Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513777-9

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Anthony, David; Ringe, Don (2015), "The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives", Annual Review of Linguistics, 1: 199–219, doi:10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-124812

- Atkinson, Quentin; Geoff Nicholls, David Welch, Russell Gray (2005) From words to dates: water into wine, mathemagic or phylogenetic inference? Transactions of the Philological Society, 103 (2):193–219

- Bouckaert, Remco; Lemey, Philippe; Dunn, Michael; Greenhill, Simon J.; Alekseyenko, Alexander V.; Drummond, Alexei J.; Gray, Russell D.; Suchard, Marc A.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (2012). "Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family". Science. 337 (6097): 957–960. doi:10.1126/science.1219669. PMC 4112997

. PMID 22923579.

. PMID 22923579. - Bomhard, Allen (2015), The Origins of Proto-Indo-European: The Caucasian Substrate Hypothesis

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2000). Genes, peoples, and languages. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-86547-529-6.

- Gray, Russell D.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin". Nature. 426 (6965): 435–439. doi:10.1038/nature02029.

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe" (PDF). Nature. doi:10.1038/nature14317.

- Koerner, E.F.K., Linguistics and Ideology in the Study of Language

- Kortlandt, Frederik (2010), An outline of proto-indo-european (working paper) (PDF)

- Lazaridis (2016b), Supplementary Information. The genetic structure of the world's first farmers

- Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson

- Mallory, J.P. (1996), Fagan, Brian M., ed., The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-507618-4

- Mallory, James P. (1997), "The homelands of the Indo-Europeans", in Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, Archaeology and Language, I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-11760-7.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (2006), The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world (Repr. ed.), Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, ISBN 9780199287918

- Mallory, J.P. (2013), "Twenty-first century clouds over Indo-European homelands" (PDF), Journal of Language Relationship, 9

- Mascarenhas, Desmond D.; Raina, Anupuma; Aston, Christopher E.; Sanghera, Dharambir K. (2015), "Genetic and Cultural Reconstruction of the Migration of an Ancient Lineage", BioMed Research International, 2015: 651415, doi:10.1155/2015/651415

- Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Németh, Endre; Pádár, Zsolt (2012), "Brief communication: new Y-chromosome binary markers improve phylogenetic resolution within haplogroup R1a1", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 149 (4): 611–615, doi:10.1002/ajpa.22167, PMID 23115110

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilisation, Oxford University Press

- Pereltsvaig, Asya; Lewis, Martin W. (2015), "Searching for Indo-European origins", The Indo-European Controversy, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107054530

- Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi (2006). "Diffusion of genes and languages in human evolution". Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Evolution of Language. pp. 255–266.

- Poznik (2016), "Punctuated bursts in human male demography inferred from 1,244 worldwide Y-chromosome sequences", Nature Genetics, doi:10.1038/ng.3559

- Renfrew, Colin (1990). Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521386753.

- Underhill, Peter A. (2015), "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a", European Journal of Human Genetics, 23: 124–131, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

- Calvert Watkins. "Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000". Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The journey of man: a genetic odyssey. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11532-0.

- Zvelebil (1995), "Indo-European origins and the agricultural transition in Europe", Whither Archaeology?: papers in honour of Evžen Neustupný

Further reading

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

External links

- Stephanie Dutchen (2014), New Branch Added to European Family Tree. Genetic analysis reveals Europeans descended from at least three ancient groups

- Richard Gray (2015), Modern Europeans descend from FOUR groups of hunter-gatherers: New strand of DNA discovered in the Caucasus is the 'missing piece in the ancestry puzzle'

- Dieneke's Anthropology Blog, West_Asian in the flesh (hunter-gatherers from Georgia) (Jones et al. 2015)

- For what they were... we are (2016), Caucasus and Swiss hunter-gatherer genomes

- eurogenes.blogspot, The genetic structure of the world's first farmers (Lazaridis et al. preprint)

- For what they were... we are (2016) Ancient genomes from Neolithic West Asia