Croatia and the euro

-

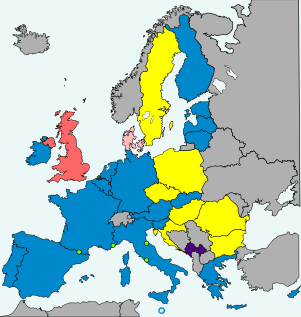

<dt class="glossary " id="European Union (EU) member states" style="margin-top: 0.4em;">European Union (EU) member states

- Non-EU member states

Croatia's currency, the kuna, has used the euro (and prior to that one of the euro's major predecessors, the German mark or Deutschmark) as its main reference since its creation in 1994, and a long-held policy of the Croatian National Bank has been to keep the kuna's exchange rate with the euro within a relatively stable range.

Croatia's EU membership obliges it to eventually join the eurozone, as such the country plans to join the European Monetary System, the pathway to euro adoption.[2][3] Prior to Croatian entry to the EU on 1 July 2013, Boris Vujčić, governor of the Croatian National Bank, stated that he would like the kuna to be replaced by the euro as soon as possible after accession.[4] This must be at least two years after Croatia joins the ERM2 (in addition to it meeting other criteria). The Croatian National Bank had anticipated euro adoption within two or three years of EU entry.[3][5] However, the EU's response to the ongoing financial crises in eurozone states may delay Croatia's adoption of the euro.[6] The country's own contracting economy also poses a major challenge to it meeting the convergence criteria.[7] While keen on euro adoption, one month before Croatia's EU entry governor Vujčić admitted "...we have no date [to join the single currency] in mind at the moment".[4] Before Croatia can join ERM II, it must reduce its budget deficit by about 1.5 billion kuna (June 2013 figures). The European Central Bank expects Croatia to be approved for ERM II membership in 2016 at the earliest, with euro adoption in 2019.[8][9]

Many small businesses in Croatia had debts denominated in euros before EU accession.[10] Croatian people already use the euro for most savings and many informal transactions. Real estate, motor vehicle and accommodation prices are mostly quoted in euros.

Public opinion

According to a eurobarometer poll in April 2015, 53% of Croatians are in favour of introducing the euro while 40% are opposed, roughly unchanged from 2014.[11][12]

Convergence Status

In its first assessment under the convergence criteria in May 2014, the country satisfied the inflation, interest rate and legislation compatibility criteria, but did not satisfy the public finances and ERM membership criteria.[13] Its second convergence report published in June 2016 came to the same conclusions.

| Convergence criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[14][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[15] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[16][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

| Budget deficit to GDP[17] | Debt-to-GDP ratio | ERM II member[18] | Change in rate[19][20][nb 3] | |||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 5] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[23] | |||||

| |

1.1% | Open | No | -0.8% | 4.8% | Yes | ||

| 4.9% | 67.1% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 7] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 8] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[26] | |||||

| |

-0.4% | Open | No | 0.3% | 3.7% | Yes | ||

| 3.2% | 86.7% | |||||||

- Notes

- ↑ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ↑ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ↑ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[21]

- 1 2 Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states.[21]</ref>

(as of 30 Apr 2014) s currency, the [[Croatian ku None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) of the euro's major predecess Min. 2 years

(as of 30 Apr 2014) s main reference since its cr Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2013) ly stable range. Croatia's Max. 6.2%[nb 5]

(as of 30 Apr 2014) e [[European Monetary System] Yes[22]

(as of 30 Apr 2014) h ubrovnik economic conference, Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2013)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2014'>"European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014. - 1 2 The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[24]

- 1 2 Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states.[24]</ref>

(as of 30 Apr 2016) s currency, the [[Croatian ku None open (as of 18 May 2016) of the euro's major predecess Min. 2 years

(as of 18 May 2016) s main reference since its cr Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2015) ly stable range. Croatia's Max. 4.0%[nb 8]

(as of 30 Apr 2016) e [[European Monetary System] Yes[25]

(as of 18 May 2016) at the tenth Dubrovnik economic Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2015)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2016'>"European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

Target date for euro adoption

In April 2015, President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović stated in a Bloomberg interview she was "confident that Croatia would introduce the euro by 2020", while Prime Minister Zoran Milanović said at the government session that "some occasional announcements when Croatia will introduce the euro shouldn't be taken seriously. We'll try to make it as soon as possible, but I distance myself from any dates and ask that you don't comment on it. When the country is ready, it will enter the euro area. The criteria are very clear."[30]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received recognition as an independent state from 110 out of 193 United Nations member states.

References

- ↑ "Bank Governor Determined For Croatia To Adopt Euro Currency ASAP". www.croatiaweek.com. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ "Monetary policy and ERM II participation on the path to the euro". Speech by Lucas Papademos, Vice President of the ECB at the tenth Dubrovnik economic conference, in Dubrovnik. European Central Bank. 2004-06-25.

- 1 2 "Vujčić: uvođenje eura dvije, tri godine nakon ulaska u EU". Poslovni dnevnik (in Croatian). HINA. 1 July 2006. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

statements made by Boris Vujčić, deputy governor of the Croatian National Bank (now governor (2013)), at the Dubrovnik economic conference, June 2006

- 1 2 THOMSON, AINSLEY. "Croatia Aims for Speedy Adoption of Euro". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ "Croatia ready to join EU in 2013 – official". reuters.com. 10 June 2011.

- ↑ "No Euro for Croatia before 2017". Croatian Times. 2010-05-31.

- ↑ "Approaching storm. Report on transformation" (PDF). www.pwc.pl. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ "Konferencija HNB-a u Dubrovniku: Hrvatska može uvesti euro najranije 2019.". www.banka.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ "Croatia country report" (PDF). http://www.rbinternational.com. June 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Joy, Oliver (21 January 2013). "Did Croatia get lucky on EU membership?". CNN.

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_400_en.pdf

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_418_en.pdf

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑ "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "The corrective arm". European Commission. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "What is ERM II?". European Commission. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑

- ↑ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ↑ "Deficit to fall below 3 pct of GDP, public debt to stop rising by 2017". Government of the Republic of Croatia. 30 April 2015.