Deshastha Brahmin

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Est. 20 lakh (2 Million)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Maharashtra • Karanataka, Madhya Pradesh (Gwalior, Indore, Ujjain, Dhar) Gujarat (Baroda) • Thanjavur • Delhi • United States • UK | |

| Languages | |

| First language – Marathi (Majority) and Kannada | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Karhade • Konkanastha • Devrukhe • Daivadnya Brahmin Goud Saraswat Brahmin•Thanjavur Marathi • Marathi people |

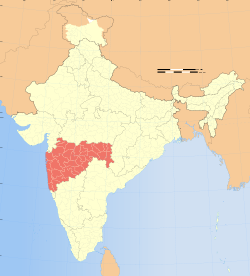

Deshastha Brahmins are a Hindu Brahmin subcaste mainly from the Indian state of Maharashtra and northern area of the state of Karnataka. The word Deshastha derives from the Sanskrit deśa (inland, country) and stha (resident), literally translating to "residents of the country". The valleys of the Krishna and the Godavari rivers, and a part of Deccan plateau adjacent to the Sahyadri hills, are collectively termed the Desha – the original home of the Deshastha Brahmins.

Over the millennia, the community produced the eighth century Sanskrit scholar Bhavabhuti, the thirteenth century Varkari saint and philosopher Dnyaneshwar, and Samarth Ramdas. All of the Peshwas during the time of Chhatrapati Shivaji and Sambhaji's reign (before the appointment in 1713 of Balaji Vishwanath, the first Peshwa from the Bhat family) were Deshastha Brahmins.[1]

Brahmins constitute four percent of Maharashtra's population, and 60 percent of them are Deshastha Brahmins. The second largest Maharashtrian Brahmin community, the Konkanastha Brahmins, who historically remained rather obscure because their native region, the coastal Konkan strip, was relatively distant from the great medieval cities, achieved parity with the Deshasthas only during the 18th century, after the post of Peshwa became effectively hereditary in the Bhat family of Konkanastha Brahmins.[2][3]

Classification

The Hindu caste system[note 1] is first mentioned in the ancient Hindu scriptures like the Vedas and the Upanishads.[note 2] Various sub-classifications of the caste system exist, many based on the geographical origin of the caste.[note 3][note 4]

Deshastha Brahmins fall under the Pancha Dravida Brahmin classification of the Brahmin community in India. Other Brahmin sub-castes in the region are Karhade Brahmin, Devrukhe, Konkanastha and Goud Saraswat Brahmin, but these sub-castes only have a regional significance.[11] Goud Saraswat Brahmins fall under the Pancha Gauda Brahmin classification, i.e. North Indian Brahmins. The Vedas are the world's oldest texts that are still used in worship and they are the oldest literature of India. Four Vedas exist of which the Rig Veda is the oldest. They were handed down from one generation of Brahmins to the next verbally and memorised by each generation. They were written down sometime around 400 BC.[12] Other Vedas include the Yajur Veda, the Atharva Veda and the Sama Veda. Two different versions of the Yajur Veda exist, the White (Shukla in Sanskrit) and the black or (Krishna in Sanskrit). The Shukla Yajur Veda has a two different branches (Shakha in Sanskrit) called the Kanva and the Madhyandin. Deshastha Brahmins are further classified in two major sub-sects, the Deshashatha Rigvedi and the Deshastha Yajurvedi, based on the Veda they follow. The Yajurvedis are further classified into two groups called the Madhyandins and the Kanavas. The Madhyandins follow the Madhyandin branch of the Shukla Yajur Veda.[13] The word Madhyandin is a fusion of two words Madhya and din which mean middle and day respectively. They are so called because they perform Sandhya Vandana at noon.[14] Almost without exception, the several regional groups of the Madhyandin Brahmins are indistinguishable from the Kshatriya Marathas due to similar physical features.[15] A similar study of four groups that have been resident in Mumbai and surrounding areas for generations, using blood group markers, found the Deshastha Rigvedi and the Marathas to be genetically closer to each other than to the Gujarati Patel and the Parsi communities.[16] Kannav Brahmins were traditionally located in and around Nasik, and they call themselves Prathamshakhis or followers of the first branch of the White Yajurved.[17] The Madhyandin Yajurvedis arrived in the Nashik district of Maharashtra from Gujarat about 500 years ago.[17]

| Veda followed | Recension or sub-part of the veda | Shakha or branch of the veda | Brahmin Nomenclature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rig Veda (composed: 1500 bc – 1400 bc)[18] | No recension or sub-parts exist | Śākalya (only one survives) | Deshastha Rigvedi |

| Yajur Veda (composed: 900 bc – 700 bc)[18] | Shukla (White) | Madhyandin | Yajurvedi Madhyandin |

| Kannava | Yajurvedi Kannava | ||

| Krishna (Black) | Irrelevant for Deshasthas | Irrelevant for Deshasthas | |

Recently, the Yajurvedi Madhyandin and Yajurvedi Kannava Brahmins have been colloquially being referred to as Deshastha Yajurvedi Madhyandin and Deshastha Yajurvedi Kannava, although not all have traditionally lived or belonged to the Desh.

The Deshastha Rigvedi Brahmins are treated as a separate and distinct caste from the Yajurvedi Madhyandina and Kannavas Brhamins by several authors, including Malhotra, Karve and Wilson.[19][20]

There is a significant Deshashta population in the state of Karnataka, and here, the sub-classification of Deshastha Brahmins is based on the type of Hindu philosophical system they follow. These are the Deshastha Madhva Brahmins[21] who follow the teachings of Madhvacharya and the Deshastha Smartha[22] Brahmins who follow the teachings of Adi Shankaracharya. The surnames of these North Kanataka based, Kannada speaking Deshastha Brahmins, can be identical to those of Maharashtrian Deshastha Brahmins, for example, they have last names like Kulkarni, Deshpande and Joshi. Intermarriages are allowed between the Karnatak Brahmans and the Deshasthas and so the classification of the Southern India Brahmans into the Maharashtra, the Andhra (Telugu) and the Karnatic are in this respect, more of a provincial or linguistic character than an ethnographic one.[23]

| Varna | Caste | Literate | In English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmin | Deshastha | 83.7 | 35.6 |

| Konkanastha | 63 | 19.3 | |

| Saraswat | 54 | 10.77 | |

| Kshatriya | Maratha | 74 | 19.8 |

| Intermediate Varnas | Kunbi | 9.4 | 0.27 |

| Lingayat | 13.6 | 0.3 | |

| Schedule Caste | Mahars | 1 | 0.01 |

Demographics

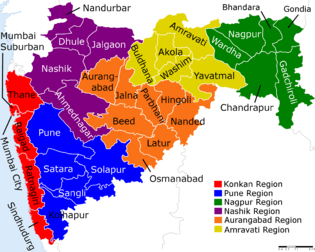

Brahmins constitute 4 percent of the population of Maharashtra, and 60 percent of them are Deshastha Brahmins.[25][26][note 5] The valleys of the Krishna and the Godavari rivers, and the plateaus of the Sahyadri hills, are collectively called the Desha – the original home of the Deshastha Brahmins.[28] Traditional social studies and recent genetic studies show Deshastha Brahmin to be ethnically indistinguishable from the population of Maharashtra.[29][30][15] In his report on the 1901 census, Sir Herbert Hope Risley classified many castes from Western India including Maratha, Brahman and Kunbis as belonging to the Scytho-Dravidian type.[31]

The Deshastha Brahmins are equally distributed all through the state of Maharashtra, ranging from villages to urban areas.[32][33][34] Marathi speaking Deshastha can also be found in large numbers outside Maharashtra such as in the cities of Indore, Gwalior, Baroda and Thanjavur, which were a part of or were influenced by, the Maratha Empire. The Deshastha Brahmins of Baroda are immigrants who came from the Desh for State service during the rule of Gaekwads.[35]

The military settlers (of Thanjavur) included both Brahmins and Marathas, and by reason of their isolation from their distant home, the sub-divisions which separated these castes in their mother-country were forgotten, and they were all welded together under the common name of Deshasthas.[36][37] The Brahmin migrants and the Maratha migrants both call themselves "Deshasthas" as both groups migrated to Tanjore from the Desh region of Maharashtra, but till today maintain their separate identities, despite the common "Deshastha" tag. Today's Marathi speaking Thanjavur population are descendants of the Marathi speaking immigrants who immigrated to Tamil Nadu in the 17th and 18th centuries.[38] The isolation from their homeland has almost made them culturally and linguistically alien to Brahmins in Maharashtra.[39] For example, Thanjavur Marathi would sound as a strange mixture of Marathi and Tamil to a Maharashtrian in Pune and would hardly be intelligible to him. Likewise a Tanjore Maharashtrian would find it difficult to follow Pune Marathi. Tanjore Maharashtrian Brahmins who call themselves Deshasthas maintain their distinct brahminical identity which can be seen in their religious and wedding customs. Almost all their customs can be traced to the practices conducted by the early Maharashtrian settlers of Tanjore. They belong to two major groups, the Madhwa Deshastha Brahmins and Smartha Deshastha Brahmins. Arranged marriages between these two groups are common. Both these sub-groups do not conduct arranged marriages with the Maratha caste of Tanjavur. However, Madhwa Deshastha Brahmins and Smartha Deshastha Brahmins of Tanjavur conduct arranged marriages with Madhwa Kannada Brahmins and Smartha Kannada Brahmins. In 2000, a 90-year-old community member estimated that there had been 500 Marathi families in a particular neighbourhood of Tanjavur in 1950, of which only 50 remained in 2000.

History

The word Deshastha comes from the Sanskrit words Desha and Stha, which mean inland or country and resident respectively. Fused together, the two words literally mean "residents of the country".[40] Deshastha are the Maharashtrian Brahmin community with the longest known history,[11][41] making them the original[33][42][43] and the oldest Hindu Brahmin sub-caste from the Indian state of Maharashtra.[11][41][44] The Deshastha community may be as old as the Vedas, as vedic literature describes people strongly resembling Deshasthas.[45] This puts Deshastha presence on the Desh between 1100–1700 BC,[46] thus making the history of the Deshastha Brahmins older than that of their mother tongue of Marathi, which itself originated in 1000 AD.[47] As the original Brahmins of Maharashtra, the Deshasthas have been held in the greatest esteem in Maharashtra and they have considered themselves superior to other Brahmins.[48][33][42] The history of Maharashtra before the 12th century is quite sparse, but Deshastha history is well documented. The traditional occupation of the Deshasthas was that of priesthood at the Hindu temples or at socio-religious ceremonies. Records show that most of the religious and literary leaders since the 13th century have been Deshasthas. In addition to being village priests, most of the village accountants belonged to the Deshastha caste.[33] Priests at the famous Vitthal temple in Pandharpur are Deshastha, as are the priests in many of Pune's temples.[49][50] Other traditional occupations included village revenue officials, academicians, astrologer, administrators and practitioners of Ayurvedic medicine.[51] Deshasthas who study the vedas are called Vaidika, astrologers are called Jyotishi or Joshi, and practitioners of medical science are called Vaidyas, and reciters of the puranas are called Puraniks. Some are also engaged in farming. An author recorded in 1896 that Deshasthas have been and still continue to be, the great Pandits in almost every branch of Sanskrit learning.[52] According to the Anthropological Survey of India, the Deshasthas are a progressive community and some of them have taken to white collar jobs.[53] The Deshastha Brahmins helped build the Maratha Empire and once built, helped in its administration. Deshasthas have contributed to the fields of Sanskrit and Marathi literature, mathematics, and philosophy.

Mathematics, philosophy and literature

Deshasthas produced prominent literary figures in Maharashtra between the 13th and the 19th centuries.[54] The great Sanskrit scholar Bhavabhuti was a Deshastha Brahmin who lived around 700 AD in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra.[55][56] His works of high Sanskrit poetry and plays are only equalled by those of Kalidasa. Two of his best known plays are Mahāvīracarita and Mālatī Mādhava. Mahaviracarita is a work on the early life of the Hindu god Rama, whereas Malati Madhava is a love story between Malati and her lover Madhava, which has a happy ending after several twists and turns. Mukund Raj was another poet from the community who lived in the 13th century and is said to be the first poet who composed in Marathi.[57] He is known for the Viveka-Siddhi and Parammrita which are metaphysical, pantheistic works connected with orthodox Vedantism. Other well known Deshastha literary scholars of the 17th century were Mukteshwar and Shridhar.[57] Mukteshwar was the grandson of Eknath and is the most distinguished poet in the ovi meter. He is most known for translating the Mahabharata and the Ramayana in Marathi but only a part of the Mahabharata translation is available and the entire Ramayana translation is lost. Shridhar Kulkarni came from near Pandharpur and his works are said to have superseded the Sanskrit epics to a certain extent. Other major literary contributors of the 17th and the 18th century were Vaman Pandit, Mahipati, Amritaraya, Anant Phandi and Ramjoshi.[57]

The 17th century mathematician Kamalakara, was a forward-looking astronomer-mathematician who studied Hindu, Greek and Arabic astronomy. His most important work was the Siddhanta-Tattvaviveka. He studied and agreed with Ptolemaic notions of the planetary systems. He was the first and the only traditional astronomer to present geometrical optics. Kamalakara proposed a new Prime Meridian which passed through the imaginary city of Khaladatta, and provided a table of latitudes and longitudes for 24 cities within and outside of India.[58]

The Deshastha community has produced several saints and philosophers. Most important of these were Dnyaneshwar, Eknath and Ramdas.[59] The most revered of all Bhakti saints, Dnyaneshwar was universally acclaimed for his commentary on the Bhagvad Gita. He lived in the 13th century.[57] Eknath was yet another Bhakti saint who published an extensive poem called the Eknathi Bhagwat in the 16th century. Other works of Eknath include the Bhavartha Ramayana, the Rukmini Swayamwara and the Swatma Sukha.[57] The 17th century saw the Dasbodh of the saint Samarth Ramdas, who was also the spiritual adviser to Shivaji.[57]

Military and administration

Most of Shivaji's principal Brahmin officers were Deshasthas.[60] Some important contributors were warriors like Neelkanth Sarnaik, Keso Narayan Deshpande, Rahuji Somanath, Balaji and Chimnaji Deshpande of Pune, Ragho Ballal Atre, Moropant Pingale, Annaji Dato Sabnis and Melgiri Pandit.[61] At one point in Maratha Empire, seven of eight Ashtapradhans came from the community which included important posts of Panditrao (ecclesiastical head) and Nyayadhish (chief justice). The Deshasthas were the natural leaders in the era of the foundation of the Maratha empire.[62] Most importantly, all of the Peshwas during Shivaji's time were Deshasthas.[63] In 1713, Balaji Vishwanath Bhat was appointed as the fifth Peshwa and the seat of Peshwa remained in Konkanastha hands until the fall of the Maratha Empire. In order to obtain the loyalty of the powerful Deshastha Brahmins, the Konkanastha Peshwas established a system of patronage for Brahmin scholars.[64]

The Konkanastha Peshwa Baji Rao I who coveted conquering Vasai or Bassein, sent an enovy to the Portuguese governor of Bassein. The governor, Luís Botelho, insulted the envoy by calling Baji Rao a nigger.[65] The Peshwa then deployed his brother, Chimaji Appa in the conquest of Vasai. This was a hard fought battle with the British supplying the Portuguese with advice and the Marathas with equipment. Khanduji Mankar of the Pathare Prabhu caste and Antaji Raghunath, a Yajurvedi Brahmin, both played important roles in the battle. After the victory in 1739, the Jagir of Vasai was promised to Antaji Raghunath, but the promise was not kept by the Konkanastha Peshwas, who instead harassed the Yajurvedis. Fed up with the humiliation, the Yajurvedi Brahmins migrated to Mumbai along with the Pathare Prabhus to work for the British.[66]

Society and culture

The majority of Deshasthas speak Marathi, one of the major languages of the mainly northern Indo-Aryan language group. The major dialects of Marathi are called Standard Marathi and Warhadi Marathi.[67] Standard Marathi is the official language of the State of Maharashtra. The language of Pune's Deshastha Brahmins has been considered to be the standard Marathi language and the pronunciation of the Deshastha Rigvedi is given prominence.[68] There are a few other sub-dialects like Ahirani, Dangi, Samavedi, Khandeshi and Chitpavani Marathi. There are no inherently nasalised vowels in standard Marathi whereas the Chitpavani dialect of Marathi does have nasalised vowels.[67]

By tradition, like other Brahmin communities of Southern India, Deshastha Brahmins are lacto vegetarian.[51] Typical Deshastha cuisine consists of the simple varan made from tuvar dal. Metkut, a powdered mixture of several dals and a few spices is also a part of traditional Deshastha cuisine. Deshastha use black spice mix or kala, literally black, masala, in cooking. Traditionally, each family had their own recipe for the spice mix. However, this tradition is dying out as modern households buy pre-packaged mixed spice directly from supermarkets. Puran poli for festivals and on the first day of the two-day marriage is another Marathi Brahmin special dish.

Most middle aged and young women in urban Maharashtra dress in western outfits such as skirts and trousers or shalwar kameez with the traditionally nauvari or nine-yard sari, disappearing from the markets due to a lack of demand. Older women wear the five-yard sari. Traditionally, Brahmin women in Maharashtra, unlike those of other castes, did not cover their head with the end of their saree.[69] In urban areas, the five-yard sari is worn by younger women for special occasions such as marriages and religious ceremonies. Maharashtrian brides prefer the very Maharashtrian saree – the Paithani – for their wedding day.[70]

In early to mid 20th century, Deshastha men used to wear a black cap to cover their head, with a turban or a pagadi being popular before that.[71] For religious ceremonies males wore a coloured silk dhoti called a sovale. In modern times, dhotis are only worn by older men in rural areas. In urban areas, just like women, a range of styles are preferred. For example, the Deshastha politician Manohar Joshi prefers white fine khadi kurtas,[72] while younger men prefer modern western clothes such as jeans.

In the past, caste or social disputes used to be resolved by joint meetings of all Brahmin sub-caste men in the area.[73][74][17]

Religious customs

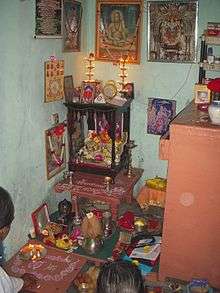

Deshastha Rigvedi Brahmins still recite the Rig Veda at religious ceremonies, prayers and other occasions.[32] These ceremonies include birth, wedding, initiation ceremonies, as well as death rituals. Other ceremonies for different occasions in Hindu life include Vastushanti which is performed before a family formally establishes residence in a new house, Satyanarayana Puja, originating in Bengal in the 19th century, is a ceremony performed before commencing any new endeavour or for no particular reason. Invoking the name of the family's gotra and the kula daivat are important aspects of these ceremonies. Like most other Hindu communities, Deshasthas have a shrine called a devaghar in their house with idols, symbols, and pictures of various deities. Ritual reading of religious texts called pothi is also popular.

In traditional families, any food is first offered to the preferred deity as naivedya, before being consumed by family members and guests. Meals or snacks are not taken before this religious offering. In contemporary Deshasthas families, the naivedya is offered only on days of special religious significance.

Deshasthas, like all other Hindu Brahmins, trace their paternal ancestors to one of the seven or eight sages, the saptarshi. They classify themselves into eight gotras, named after the ancestor rishi. Intra-marriage within gotras (Sagotra Vivaha) was uncommon until recently, being discouraged as it was likened to incest, although the taboo has considerably reduced in the case of modern families who are bound by more practical considerations.

In a court case "Madhavrao versus Raghavendrarao", involving a Deshastha Brahmin couple, the German philosopher and Indologist Max Müller's definition of gotra as descending from eight sages and then branching out to several families was thrown out by reputed judges of a Bombay High Court.[75] The court called the idea of Brahmin families descending from an unbroken line of common ancestors as indicated by the names of their respective gotras impossible to accept.[76] The court consulted relevant Hindu texts and stressed the need for Hindu society and law to keep up with the times emphasising that notions of good social behaviour and the general ideology of Hindu society had changed.[75] The court also said that the mass of material in the Hindu texts are so vast and full of contradictions that it is almost an impossible task to reduce it to order and coherence.[75]

Every Deshastha family has their own family patron deity or the Kuladaivat.[77] This deity is common to a lineage or a clan of several families who are connected to each other through a common ancestor.[77][78] The Khandoba of Jejuri is an example of a Kuladaivat of some Maharashtrian Deshastha families; he is a common Kuladaivat to several castes ranging from Brahmins to Dalits.[79] The practice of worshiping local or territorial deities as Kuladaivats began in the period of the Yadava dynasty.[78] Other family deities of the people of Maharashtra are Bhavani of Tuljapur, Mahalaxmi of Kolhapur, Mahalaxmi of Amravati, Renuka of Mahur, Parashuram in Konkan, Saptashringi on Saptashringa hill at Vani in Nasik district. Despite being the most popular deity amongst Deshastha and other Marathi people, very few families regard Vitthal or other popular Avatars of Vishnu such as Rama or Krishna as their Kuldaivat, with Balaji being an exception.

Ceremonies and rituals

Upon birth, a child is initiated into the family ritually according to the Rig Veda for the Rigvedi Brahmins. The naming ceremony of the child may happen many weeks or even months later, and it is called the barsa. In many Hindu communities around India, the naming is almost often done by consulting the child's horoscope, in which are suggested various names depending on the child's Lunar sign (called Rashi). However, in Deshastha families, the name that the child inevitably uses in secular functioning is the one decided by his parents. If a name is chosen on the basis of the horoscope, then that is kept a secret to ward off casting of a spell on the child during his or her life. During the naming ceremony, the child's paternal aunt has the honour of naming the infant. When the child is 11 months old, he or she gets their first hair-cut.[51] This is an important ritual as well and is called Jawal.

When a male child[51] reaches his eighth birthday he undergoes the initiation thread ceremony variously known as Munja (in reference to the Munja grass that is of official ritual specification), Vratabandha, or Upanayanam.[80] From that day on, he becomes an official member of his caste, and is called a dwija which translates to "twice-born" in English, in the sense that while the first birth was due to his biological parents, the second one is due to the initiating priest and Savitri.[note 6][81] Traditionally, boys are sent to gurukula to learn Vedas and scriptures. Boys are expected to practice extreme discipline during this period known as brahmacharya. Boys are expected to lead a celibate life, live off alms, consume selected vegetarian saatvic food and observe considerable austerity in behaviour and deeds. Though such practices are not followed in modern times by a majority of Deshasthas, all Deshasthas boys undergo the sacred thread ceremony. Many still continue to get initiated around eight years of age. Those who skip this get initiated just before marriage. Twice-born Deshasthas perform annual ceremonies to replace their sacred threads on Narali Purnima or the full moon day of the month of Shravan, according to the Hindu calendar. The threads are called Jaanave in Marathi and Janavaara in Kannada.

The Deshasthas are historically an endogamous and monogamous community[51] for whom marriages take place by negotiation. The Mangalsutra is the symbol of marriage for the woman. Studies show that most Indians' traditional views on caste, religion and family background have remained unchanged when it came to marriage,[82] that is, people marry within their own castes,[83] and matrimonial advertisements in newspapers are still classified by caste and sub-caste.[84] In 1907, Rivers and Ridgeway record that Deshasthas allowed cross cousin marriages, just like other South Indian castes.[85][86][87]

While arranging a marriage, gana, gotra, pravara, devak are all kept in mind. Horoscopes are matched.[88] Ghosal describes the marriage ceremony as, "The groom, along with the bride's party goes to the bride's house. A ritual named Akshat is performed in which people around the groom and bride throw haldi (turmeric) and sindur (vermilion) coloured rice grains on the couple. After the Kanyadan ceremony, there is an exchange of garlands between the bride and the groom. Then, the groom ties the Mangalsutra around the neck of the bride. This is followed by granthibandhan in which the end of the bride's sari is tied to the end of the groom's dhoti, and a feast is arranged at the groom's place."

A Deshasthas marriage ceremony includes many elements of a traditional Marathi Hindu wedding ceremony. It consists of seemant poojan on the wedding eve. The dharmic wedding includes the antarpat ceremony followed by the vedic ceremony which involves the bridegroom and the bride walking around the sacred fire seven times to complete the marriage. Modern urban wedding ceremonies conclude with an evening reception. A Deshastha woman becomes part of her husband's family after marriage and adopts the gotra as well as the traditions of her husband's family.[note 7]

After weddings and also after thread ceremonies, Deshastha families arrange a traditional religious singing performance by a Gondali group [92]

Decades ago, Deshastha girls used to get married to the groom of their parents' choice by early teens or before. Even today, girls are married off in their late teens by rural and less educated amongst Deshastha. Urban women may choose to remain unmarried until the late 20s or even early 30s.

The 1881 Kolhapur gazetteer records that Deshastha widows at that time used to shave their heads and wear simple red saris.[93] A widow also had to stop wearing the kunku on her forehead.[71] In the past, a Deshastha widow was never allowed to remarry, while it was acceptable for Deshastha widowers to remarry, and the widows had to lead a very austere life with little joy. Divorces were non-existent. All of these practices have gradually fallen by the wayside over the last hundred years, and modern Deshastha widows lead better lives and younger widows also remarry. Divorce takes place by mutual consent and legal approval is sought.

Deshastha Brahmins dispose their dead by cremation.[88] The dead person's son carries the corpse to the cremation ground atop a bier. The eldest son lights the fire to the corpse at the head for males and at the feet for females. The ashes are gathered in an earthen pitcher and immersed in a river on the third day after the death. This is a 13-day ritual with the pinda being offered to the dead soul on the 11th and a Śrāddha ceremony followed by a funeral feast on the 13th. Cremation is performed according to vedic rites, usually within a day of the individual's death. Like all other Hindus, the preference is for the ashes to be immersed in the Ganges river or Godavari river. Śrāddha becomes an annual ritual in which all forefathers of the family who have passed on are remembered. These rituals are expected to be performed only by male descendants, preferably the eldest son of the deceased.

Festivals

Deshasthas follow the Saka calendar. They follow several of the festivals of other Hindu Marathi people. These include Gudi Padwa, Rama Navami, Hanuman Jayanti, Narali Pournima, Mangala Gaur, Krishna Janmashtami, Ganesh Chaturthi, Kojagiri Purnima, Diwali, Khandoba Festival (Champa Shashthi), Makar Sankranti, Maha Shivaratri and Holi.

Of these, Ganesh Chaturthi is the most popular in the state of Maharashtra,[94] however, Diwali, the most popular festival of Hindus throughout India,[95] is equally popular in Maharashtra. Deshasthas celebrate the Ganesha festival as a private, domestic family affair. Depending on a family's tradition, a clay image or shadu is worshiped for one and a half, three and a half, seven or full 10 days, before ceremoniously being placed in a river or the sea.[96] This tradition of private celebration runs parallel to that of public celebration introduced in 1894 by Bal Gangadhar Tilak.[97] Modak is a popular food item during the festival. Ganeshotsav also incorporates other festivals, namely Hartalika and the Gauri festival, the former is observed with a fast by women whilst the latter by the installation of idols of Gauris.[98]

The religious amongst the Deshasthas fast on the days prescribed for fasting according to Hindu calendar.[99] Typical days for fasting are Ekadashi, Chaturthi, Maha Shivaratri and Janmashtami.[100] Hartalika is a day of fasting for women. Some people fast during the week in honour of a particular god, for example, Monday for Shiva or Saturday for Hanuman and the planet Saturn, Shani.[100]

Gudi Padwa is observed on the first of the day of the lunar month of Chaitra of the Hindu calendar. A victory pole or Gudi is erected outside homes on the day. The leaves of Neem or and shrikhand are a part of the cuisine of the day.[101][102] Like many other Hindu communities, Deshasthas celebrate Rama Navami and Hanuman Jayanti, the birthdays of Rama and Hanuman, respectively, in the month of Chaitra. A snack eaten by new mothers called Sunthawada or Dinkawada is the prasad or the religious food on Rama Navami.[103] Deshastha Brahmins observe Narali-pournima festival on the same day as the much widely known north Indian festival of Raksha Bandhan. Deshastha men change their sacred thread on this day.[100]]

An important festival for the new brides is Mangala Gaur. It is celebrated on any Tuesday of Shravana and involves the worship of lingam, a gathering of womenfolk and narrating limericks or Ukhane using their husbands' first name. The women may also play traditional games such as Jhimma, and Fugadi, or more contemporary activities such as Bhendya till the wee hours of the next morning.[104]

Krishna Janmashtami, the birthday of Krishna on which day Gopalkala, a recipe made with curds, pickle, popped millet (jondhale in Marathi) and chili peppers is the special dish. Sharad Purnima also called as Kojagiri Purnima, the full moon night in the month of Ashvin, is celebrated in the honour of Lakshmi or Parvati. A milk preparation is the special food of the evening. The first born of the family is honored on this day.[71]

In Deshastha families Ganeshotsav is more commonly known as Gauri-Ganpati because it also incorporates the Gauri Festival.In some families Gauri is also known as Lakshmi puja. It is celebrated for three days; on the first day, Lakshmi's arrival is observed. The ladies in the family will bring statues of Lakshmi from the door to the place where they will be worshiped. The Kokanstha Brahmins, instead of statues, use special stones as symbols of Gauri.[105] The statues are settled at a certain location (very near the Devaghar), adorned with clothes and ornaments. On the second day, the family members get together and prepare a meal consisting of puran poli. This day is the puja day of Mahalakshmi and the meal is offered to Mahalakshmi and her blessings sought. On the third day, Mahalakshmi goes to her husband's home. Before the departure, ladies in the family will invite the neighbourhood ladies for exchange of haldi-kumkum. It is customary for the whole family to get together during the three days of Mahalakshmi puja. Most families consider Mahalakshmi as their daughter who is living with her husband's family all the year; but visits her parents' (maher) during the three days.[106][107][108][109]

Navaratri, a nine-day festival starts on the first day of the month of Ashvin and culminates on the tenth day or Vijayadashami. This is the one of three auspicious days of the year. People exchange leaves of the Apti tree as symbol of gold. During Navaratri women and girls hold Bhondla referred as bhulabai in Vidarbh region, a singing party in honour of the Goddess.

Like all Hindu Marathi people and to a varying degree with other Hindu Indians, Diwali is celebrated over five days by the Deshastha Brahmins. Deshastha Brahmins celebrate this by waking up early in the morning and having an Abhyangasnan. People light their houses with lamps and candles, and burst fire crackers over the course of the festival. Special sweets and savouries like Anarse, Karanjya, Chakli, Chiwda and Ladu are prepared for the festival. Colorful Rangoli drawings are made in front of the house. Marathi children make a replica mud fort in memory of Shivaji, the great Maratha king.[110]

Deshastha Brahmins observe the Khandoba Festival or Champa Shashthi in the month of Mārgashirsh. This is a six-day festival, from the first to sixth lunar day of the bright fortnight. Deshastha households perform Ghatasthapana of Khandoba during this festival. The sixth day of the festival is called Champa Sashthi. For Deshastha, the Chaturmas period ends on Champa Sashthi. As it is customary in many families not to consume onions, garlic and eggplant (Brinjal / Aubergine) during the Chaturmas, the consumption of these food items resumes with ritual preparation of Vangyache Bharit (Baingan Bharta) and rodga, small round flat breads prepared from jwari (white millet). [111][112]

Makar Sankranti falls on 14 January when the Sun enters Capricorn. Deshastha Brahmins exchange Tilgul or sweets made of jaggery and sesame seeds along with the customary salutation Tilgul Ghya aani God Bola, which means Accept the Tilgul and be friendly. Gulpoli, a special type of chapati stuffed with jaggery is the dish of the day.

Maha Shivaratri is celebrated in the month of Magha to honour Shiva. A chutney made from the fruit of curd fruit (Kawath in Marathi), elephant apple, monkey fruit or wood apple is a part of the cuisine of the day.

Holi falls on the full moon day in Phalguna, the last month. Deshasthas celebrate this festival by lighting a bonfire and offering Puran Poli to the fire. Unlike North Indians, Deshastha Brahmins celebrate colour throwing five days after Holi on Rangapanchami.[100]

Social and political issues

Maharashtraian Brahmins were absentee landlords and lived off the surplus without tilling the land themselves per ritual restrictions.[113] They were often seen as the exploiter of the tiller. This situation started to change when the newly independent India enshrined in its constitution, agrarian or land reform. Between 1949–1959, the state governments started enacting legislation in accordance with the constitution implementing this agrarian reform or Kula Kayada in Marathi. The legislation led to the abolition of various absentee tenures like inams and jagirs. This implementation of land reform had mixed results in different States. On official inquiry, it was revealed that not all absentee tenures were abolished in the State of Maharashtra as of 1985.[114] Other social and political issues include anti-Brahminism and the treatment of Dalits.

Inter-caste issues

Maharashtrian Brahmins were the primary targets during the anti-Brahmin riots in Maharashtra in 1948, following Mahatma Gandhi's assassination. The rioters burnt homes and properties owned by Brahmins.[115] The violent riots exposed the social tensions between the Marathas and the Brahmins.[116]

In recent history, on 5 January 2004, the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) in Pune was vandalised by 150 members of the Sambhaji Brigade, an organisation promoting the cause of the Marathas.[117] The organisation was protesting against a derogatory remark made by the American author James Laine, on Shivaji's Parentage in his book, Shivaji: A Hindu King in an Islamic Kingdom. BORI was targeted because Srikant Bahulkar, a scholar at BORI, was acknowledged in Laine's book. The incident highlighted the traditionally uncomfortable Brahmin-Maratha relationship.[117] Recently, the same organisation demanded the removal of Dadoji Konddeo from the Statue of Child Shivaji ploughing Pune's Land at Lal Mahal, Pune. They also threatened that if their demands were not met, they would demolish that part of statue themselves.[118]

Until recent times, like other high castes of Maharashtra and India, Deshastha also followed the practice of segregation from other castes considered lower in the social hierarchy. Until a few decades ago, a large number of Hindu temples, presumably with a Deshastha priest, barred entry to the so-called "untouchables" (Dalit). An example of this was the case of the 14th century saint Chokhamela. He was time and again denied entry to the Vitthal temple in Pandharpur,[119] however, his mausoleum was built in front of the gate of the temple. In the early 20th century, the Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar, while attempting to visit the temple, was stopped at the burial site of Chokhamela and denied entry beyond that point for being a Mahar.[64] Deshastha caste-fellow Dnyaneshwar and his entire family were stripped of their caste and excommunicated by the Deshasthas because of his father's return from sanyasa to family life. The family was harassed and humiliated to an extent that Dnyaneshwar's parents committed suicide.[120] Other saints of the Varkari movement like Chokhamela (Mahar caste), and Tukaram (Kunbi caste) were discriminated against by the Brahmins.[121][122]

The Maharashtra Government has taken away the hereditary rights of priesthood to the Pandharpur temple from the Badve and Utpat Deshastha families, and handed them over to a governmental committee. The families have been fighting complex legal battles to win back the rights.[123][note 8] The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an organisation founded by K. B. Hedgewar advocates Dalits being head priests at Hindu temples.[126] Deshastha Brahmins such as Dr. Govande and Mahadev Ambedkar supported and helped Dalit leaders like Mahatma Phule and Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar respectively.[127][128] Dr. Ambedkar expressed gratitude towards Mahadev Ambedkar many times in his speeches.

Deshastha-Konkanastha relations

The prominence of a Brahmin in Indian society was directly related to his virtues, values, knowledge and practice of the scriptures. Manu's list of virtues of a perfect Brahmin, according to Italian Jesuit Roberto de Nobili, in order of importance were righteousness, truthfulness, generosity, almsgiving, compassion, self-restraint and diligent work.[129] Prior to the rise of the Konkanastha Peshwas, the Konkanastha Brahmins were considered inferior in a society where the Deshasthas held socio-economic, ritual and Brahminical superiority.[130][131] As mentioned earlier, all the Peshwa during Shivaji's rule were Deshastha Brahmins and many modern families who have surname, Peshwe, are in fact Deshastha Brahmins tracing descent to Shivaji's Peshwa, Moropant Pingle or Sonopant Dabir. .[63] After the appointment of Balaji Vishwanath Bhat as Peshwa, Konkanastha migrants began arriving en masse from the Konkan to Pune,[132][133] where the Peshwa offered all important offices to the Konkanastha caste.[54] The Konkanastha kin were rewarded with tax relief and grants of land.[134] Historians point out nepotism[135][136][137][138][139][140] and corruption[138] during this time. The Sahyadri Khanda which contains the legend of the origin of the Konkanastha has been carefully suppressed or destroyed by the Konkanastha Peshwas.[141] Crawford, an early Indologist described how a Brahmin reluctantly produced the manuscript when he asked for it and that Baji Rao, in 1814, ruined and disgraced a respectable Deshastha Brahmin of Wai, found in possession of a copy of the Sahyadri Khand.[142] The Konkanasthas were waging a social war on Dehasthas during the period of the Peshwas.[2][3] By the late 18th century, Konkanasthas had established complete political and economic dominance in the region. Richard Maxwell Eaton states that this rise of the Konkanastha is a classic example of social rank rising with political fortune.[133] Since then, despite being the traditional religious and social elites of Maharashtra, the Deshastha Brahmins failed to feature as prominently as the Konkanastha.[33] However, in recent decades, there have been deshasthas who have made a mark. One such person was the late Bharatiya Janata Party politician Pramod Mahajan, who was called a brilliant strategist and had an impact nationwide.[143] Other notables include Manohar Joshi, who has been the only Brahmin chief minister of Maharashtra,[144] Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh founder Dr. Hedgewar, social activist, Baba Amte, BJP politician and Social activist, Nanaji Deshmukh and present chief minister of Maharashtra, Devendra Fadnavis. The Deshasthas looked down upon the Konkanasthas as newcomers in the 18th and 19th centuries. They refused to socialise and intermingle with them, not considering them to be Brahmins. A Konkanstha who was invited to a Deshastha household was considered to be a privileged individual, and even the Peshwas were refused permission to perform religious rites at the Deshastha ghats on the Godavari at Nasik. The Konkanasthas on their part, claimed they possessed greater intellectual ability and better political acumen.[145] During the British colonial period of 19th and early 20th century, Deshasthas dominated professions such as government administration, practice of medicine, music, legal and engineering fields, whereas Konkanasthas dominated fields like politics, social reform, journalism and education. This situation has since improved by the larger scale mixing of both communities on social, financial and educational fields, as well as with intermarriages.[146]

Community organisations

The Deshastha Rigvedi sub-caste have community organizations in many major cities such as Mumbai, Dombivali, Belgaum, Nasik, Satara etc. Most of these organizations are affiliated to Central organization of the community called Akhil Deshastha Rugvedi Brahman Madhyavarty Mandal (A. D. R. B. M.) which is located in Mumbai. The activities of ADRBM includes offering scholarships to needy students, financial aid to members, exchange of information, and Matrimonial services. The Deshastha community organizations are also affiliated to their respective local All Brahmin Umbrella Organizations.[147] Similar to the Rigvedi community, there are organizations and trusts dedicated to the welfare of the Yajurvedi sub-caste.,[148][149]

Surnames and families

A large number of Deshastha surnames are derived by adding the suffix kar to the village from which the family originally hailed.[45] For example, Bidkar came from town of Bid, Nagpurkar comes from the city Nagpur, Dharwadkar from the town of Dharwad in Karnataka, and the Marathi poet V. V. Shirwadkar, colloquially knows as Kusumagraj, came from the town of Shirwad. The names Kulkarni, Deshpande, and Joshi are very common amongst Deshastha Brahmins, and denote their professions.[150] For example, Kulkarni means revenue collector and Joshi means astrologer.[150] Some surnames simply describe physical and mental characteristics such as Hirve which means green or Buddhisagar which literally translates to ocean of intellect or "Dharmik" which means "very religious".

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ In Hinduism, communities are divided into four main social classes, also known as Varna in Sanskrit. Each class is further sub-divided into a multitude of castes. The term 'Caste Hindu' is used to refer to these four main classes.[4] The Dalits (also known as Mahars and Harijans)[4] were traditionally outside of caste system and can now be said to form a fifth group of castes. The first three Varnas in the hierarchy are said to be dvija (twice-born). They are called twice born on account of their education and these three castes are allowed to wear the sacred thread. These three castes are called the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas and the Vaishyas. The traditional caste-based occupations are priesthood for the Brahmins, ruler or warrior for the Kshatriyas and businessman or farmer for the Vaishyas. The fourth caste is called the Shudras and their traditional occupation is that of a labourer or a servant. While this is the general scheme all over India, it is difficult to fit all modern facts into it.[5] These traditional social and religious divisions in the caste system have lost their significance for many contemporary Indians except for marriage alliances.[4] The traditional pre-British Indian society, while stationary, was mobile in terms of caste. Both upward or downward mobility was possible. The most popular example of this in Maharashtra was that of Shivaji whose clan climbed up the caste system and achieved warrior caste-hood. Shivaji went on to establish the powerful Maratha Empire. Traditional avenues of mobility were shut upon the arrival of the British in India.[6]

- ↑ The Indian Constitution of 26 January 1950 outlawed untouchability and caste discrimination.[7] The constitution gives generous privileges to the Dalits in an effort to redress injustice over the ages.[8]

- ↑ The Marwari Vaisaya's from Rajasthan and Gujarat fill the void of the small Vaishyas in the state.[9]

- ↑ The original inhabitants of Maharashtra are the Adivasis tribes who fall outside the caste system.[10]

- ↑ According to the 1991 census, 81.12% of the population of Maharashtra is Hindu, 9.67% Muslim, 1.12% Christian, 6.39% Buddhist, 1.22% Jain and 0.13% of other religions.[27]

- ↑ Manusmṛti 2.70–75

- ↑ Until about 300 BC, Hindu men were about 24 years of age when they got married and the girl was always post-pubescent.[89] The social evil of child marriage established itself in Hindu society sometime after 300 BC as a response to foreign invasions.[90] The problem was first addressed in 1860 by amending the Indian Penal Code which required the boy's age to be 14 and the girls age to be 12 at minimum, for a marriage to be considered legal. In 1927, the Hindu Child Marriage Act made a marriage between a boy below 15 and a girl below 12 illegal. This minimum age requirement was increased to 14 for girls and 18 for boys in 1929. It was again increased by a year for girls in 1948. The Act was amended again in 1978 when the ages were raised to 18 for girls and 21 for boys.[91]

- ↑ While untouchability was legally abolished by the Anti-untouchability Act of 1955 and under article 17 of the Indian constitution, modern India has simply ghettoised these marginalised communities.[124] Article 25(2) of the Indian constitution empowers States to enact laws regarding temple entries.[125] The relevant Act was enacted and enforced in Maharashtra in 1956. Leaders from different times in history such as Bhimrao Ambedkar, Mahatma Phule, Savarkar, Sane Guruji fought for the cause of Dalits.

- ↑ "Surname suggest identity, status, and level of aspiration. Maharashtra is a paradise for hunters of surnames. First there is the ecology which explains presence of totemestic. names, after plants, birds animals, trees. Even though totemism is at a discount, environmentalists today are interested in ecological links in fact our study shows that Maratha and cognate groups, being autochthones, have a larger and more complex range of surnames linked with environment, history and culture. Surnames with the names of villages suffixed with kar is mostly found in Maharashtra...Titles have become surnames (kulkarni, deshpande, joshi, etc.) The occupational diversification among the Parsis shows through surnames such as bandukwala, daruwala, sopariwala, etc."[152]

Citations

- ↑ Prasad 2007, p. 88.

- 1 2 Kulkarnee 1975, p. 8.

- 1 2 Sarkar 1920, p. 430.

- 1 2 3 Lamb 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ Farquhar 2008, pp. 162–164.

- ↑ Srinivas 2007, pp. 189–193.

- ↑ Rajagopal 2007.

- ↑ Datta-Ray 2005.

- ↑ Ray 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Ray 2000, pp. 34–35.

- 1 2 3 Shrivastav 1971, p. 140.

- ↑ Grimbly 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Fernandes 1941, p. 4.

- ↑ Bhattacharya 1896, p. 86.

- 1 2 Unknown 1951, p. 98.

- ↑ Mastana & Papiha 1994, pp. 241–262.

- 1 2 3 Cooke et al. 1883.

- 1 2 Bandyopadhyaya 2008.

- ↑ Karve & Malhotra 1968, pp. 109–134.

- ↑ Wilson 1877, p. 28.

- ↑ Karnataka (India), Abhishankar & Kāmat 1990, p. 242.

- ↑ Suryanarayana 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Hassan 1920, p. 118.

- ↑ Jaffrelot 2005.

- ↑ Tyagi 2009, p. 93.

- ↑ Cashman 1975, p. 19.

- ↑ Singh, Bhanu & Anthropological Survey of India 2004, p. lviii.

- ↑ Chopra 1982, p. 4, 52–54.

- ↑ Pillai 1997, p. 38.

- ↑ Gaikwad & Kashyap.

- ↑ Risley & Gait 1903, p. 500.

- 1 2 Ghosal 2004, p. 478.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Johnson 1970, pp. 98, 55–56.

- ↑ South Asian anthropologist, 11-14, Sarat Chandra Roy Institute of Anthropological Studies, 1990, pp. 31–34, ISSN 0257-7348, retrieved 10 October 2010

- ↑ Gujarat (India) 1984, pp. 171–174.

- ↑ Ranade 1900, p. 241.

- ↑ PILC journal of Dravidic studies, 8 (1–2), Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, 1998, p. 58, retrieved 10 October 2010

- ↑ Holloman & Aruti︠u︡nov 1978, p. 225.

- ↑ Vinayak 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Bhattacharya 1896, p. 82.

- 1 2 Mandavdhare 1989, p. 39.

- 1 2 Duff 1863, p. 8.

- ↑ Johnson 2005, p. 55.

- ↑ Levinson 1992, p. 68.

- 1 2 Chopra 1982, p. 52.

- ↑ Oldenberg 1998, p. 158.

- ↑ "Marathi literature", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, retrieved 10 October 2010

- ↑ Enthoven 1920, p. 244-245.

- ↑ Zelliot & Berntsen 1988, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Campbell 1884a, p. 468.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ghosal 2004, pp. 478–480.

- ↑ Bhattacharya 1896, p. 85.

- ↑ Ghosal 2004, p. 480.

- 1 2 Patterson 2007, p. 398.

- ↑ Pandey 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ "Bhavabhuti", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, retrieved 10 October 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kher 1895, pp. 446–454.

- ↑ Selin 1997, p. 475.

- ↑ Bokil 1979, p. 18.

- ↑ Prakash 2003, p. 115.

- ↑ Kunte 1972, Chapter 9 - The Moghals In Maharashtra.

- ↑ Ranade 1900, p. 139.

- 1 2 Palsokar & Rabi Reddy 1995, p. 59.

- 1 2 Lele & Singh 1989, p. 38.

- ↑ Rawlinson 1963, pp. 405–407.

- ↑ Velkar 2010.

- 1 2 Dhoṅgaḍe & Wali 2009, pp. 11, 39.

- ↑ Nemāḍe 1990, pp. 101, 139.

- ↑ Ghurye, Govind Sadashiv (1951). Indian Costume. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. p. 180. ISBN 81-7154-403-7.

- ↑ Saraf 2004, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Campbell 1886, People.

- ↑ Deshpande 2010.

- ↑ Ahmadnagar District Gazetteer 1976b.

- ↑ Government of Maharashtra 1977.

- 1 2 3 Sen 2010.

- ↑ Anand 2010.

- 1 2 Hassan 1920, pp. 110–111.

- 1 2 Walunjkar, pp. 285–287.

- ↑ Government of Maharashtra 1962.

- ↑ Mookerji 1989, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Prasan 1997, pp. 156–158.

- ↑ Bahuguna 2004.

- ↑ Srinivasa-Raghavan 2009.

- ↑ The Economist 2010.

- ↑ Rivers & Ridgeway 1907.

- ↑ Government of Maharashtra 1974.

- ↑ Government of Maharashtra 1963.

- 1 2 Ghosal 2004, p. 479.

- ↑ Nagi 1993, pp. 6–9.

- ↑ Nagi 1993, pp. 7.

- ↑ Nagi 1993, pp. 9.

- ↑ Zelliot & Berntsen 1988, pp. 176.

- ↑ Campbell 1886, People.

- ↑ Thapan 1997, p. 226.

- ↑ Council of Social and Cultural Research, p. 28.

- ↑ Government of Maharashtra 1969.

- ↑ Bandyopādhyāẏa 2004, p. 243–244.

- ↑ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2011). 99 thoughts on Ganesha : [stories, symbols and rituals of India's beloved elephant-headed deity]. Mumbai: Jaico Pub House. p. 61. ISBN 978-81-8495-152-3. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Sharma & Gupta 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 http://ahmednagar.nic.in/gazetteer/people_feast.html

- ↑ Express News Service 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Ahmadnagar District Gazeteers 1976a.

- ↑ Bombay Gazetteer html copy,page 243

- ↑ Madhava Rao 1962.

- ↑ NasikChitpavan.org 2010, p. 1.

- ↑ Sharma, Usha (2008). Festivals In Indian Society. New Delhi: Mittal. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Bapat, Shakuntala; Karandikar, Suman. "Rural Context of Primary Education Searching for the Roots" (PDF). Retrieved 12 January 2015. See also Birbhum District Official Website.

- ↑ Gopalakrishna, B. T. (2013). Festival and Dalits. Bangalore: B. T.Gopalakrishna. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-300-68262-2. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Underhil, Muriel Marion (1921). The Hindu Religious Year. London: Humphry Milford Oxford University Press. p. 52. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "Shivaji killas express pure reverence". The Times of India. 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Gupte 1994.

- ↑ Pillai 1997, p. 192.

- ↑ Mitra 2006, p. 129.

- ↑ Haque 1986, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Mohanty 2004, p. 161.

- ↑ Dossal & Maloni 1999, p. 11.

- 1 2 Katakam 2004, pp. 17–30.

- ↑ Swamy 2008.

- ↑ Prasad 2007, p. 10-12.

- ↑ Jñānadeva 1981, p. 5.

- ↑ Eaton 2005, p. 129-130.

- ↑ Eaton 2005, p. 132.

- ↑ Press Trust of India 2000.

- ↑ Nubile 2003.

- ↑ Paswan 2003, pp. 97–110, 159–161.

- ↑ "RSS for Dalit head priests in temples", The Times of India, India Times News Network, 3 January 2007, retrieved 13 October 2010

- ↑ Sharma 2002, p. 137.

- ↑ Dr. Ambedkar Mission 2010.

- ↑ Arokiasamy 1986, pp. 55–62.

- ↑

- "Economic and political weekly". 24. Sameeksha Trust. 1989. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Rinehart 2004, p. 249.

- ↑ Gokhale 2008, p. 113.

- 1 2 Eaton 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Leach & Mukherjee 1970, pp. 101, 104–5.

- ↑ Śejavalakara 1946, pp. 24–5.

- ↑ Seal 1971, pp. 74, 78.

- ↑ Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute 1947, p. 182.

- 1 2 Sardesai 1946, p. 254.

- ↑ Śinde 1985, p. 16.

- ↑ Michael 2007, p. 95.

- ↑ Da Cunha 1877, pp. 8,325–6, 331.

- ↑ Crawford 1897, p. 127.

- ↑ Misra 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Swami & Bavadam 1999, p. 1.

- ↑ Kumar 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Hassan 1920, p. 113.

- ↑ "Deshastha Rugvedi Brahman Sangh".

- ↑ "Shukla Yajurvediya Maharastriya Brahman Madhyavarti Mandal, Pune". Charity Commissioner Of Maharashtra.

- ↑ "Shree Vishnu Deosthan (Of Yajur Shakhiya Brahman)". Charity Commissioner Of Maharashtra.

- 1 2 Karve 1968, p. 161.

- ↑ Naik 2000, p. 66.

- ↑ Singh 2004, p. xlv–xlvi.

References

- Ahmadnagar District Gazeteers (1976a), The People: Feasts and Festivals, Government of Maharashtra

- Ahmadnagar District Gazetteer (1976b), The People: Castes, Government of Maharashtra

- Anand, Pinky (18 May 2010), "The paradox of the 21st century", The Hindu, Chennai, India, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Arokiasamy, Soosai (1986), Dharma, Hindu and Christian according to Roberto de Nobili: analysis of its meaning and its use in Hinduism and Christianity, 19, Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana, ISBN 978-88-7652-565-0, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Bahuguna, Nitin Jugran (5 November 2004), The marriage market, The Hindu Business Line, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Bandyopadhyaya, JayantanujaJ (2008), Class and Religion in Ancient India, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-727-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Bandyopādhyāẏa, Śekhara (2004), From Plassey to partition: a history of modern India (illustrated ed.), Orient Blackswan, pp. 243–244, ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath (1896), Hindu Castes and sects, Thacker, Spink, ISBN 978-1-150-66711-4, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Bokil, Vinayak Pandurang (1979), Rajguru Ramdas, Kamalesh P. Bokil : sole distributors, International Book Service

- Brown, Robert (1991), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, Albany: State University of New York, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-7914-0657-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Campbell, James M., ed. (1884a), Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Volume XX - Sholapur, Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra

- Campbell, James M., ed. (1884b), Maharashtra State gazetteers, District series, 23, (revised edition of 1977), Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 September 2015

- Campbell, James M., ed. (1886), "Kolhapur District", Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, XXIV, (e-edition 2006), Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Cashman, Richard I (1975), The myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and mass politics in Maharashtra, University of California, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-520-02407-6, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Chopra, Pran Nath (1982), Religions and communities of India, Vision Books, pp. 52–54, ISBN 978-0-85692-081-3, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Gupte, B.A. (1994), Hindu holidays and ceremonials: with dissertations on origin folklore and symbols, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-0953-2

- Cooke, H. R.; Baines, J. A.; Wilson, W.H.; Charles, F. L.; Thatte, Rao Bahadur Kashinath Mahadev; Sanap, Raghuji Trimbak (1883), "Population", in Campbell, James M., Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, Volume XVI - Nasik District, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai, retrieved 10 September 2015

- Council of Social and Cultural Research, Journal of social research: Volume 15, Council of Social and Cultural Research, Bihar, Ranchi University, Dept. of Anthropology, 15

- Crawford, Arthur Travers (1897), Our troubles in Poona and the Deccan, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Crooke, William, The tribes and castes of the North-western Provinces and Oudh, Volume 2, 2, p. 422

- Da Cunha, J. Gerson (1877), "Sahyâdri-khaṇḍa", The Sahyâdri-khaṇḍa of the Skanda purâṃa: a mythological, historical, and geographical account of western India ; first edition of the Sanskrit texts with various readings, pp. 8, 325–326, 331, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Datta-Ray, Sunanda K (13 May 2005), India: An international spotlight on the caste system, The New York Times, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute (1947), "Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute", Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, Dr. A. M. Ghatage, director, Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, 8: 182, LCCN 47021378, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Deshpande, Haima (21 May 2010), Clothes maketh a politician, Indian Express, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Dhoṅgaḍe, Ramesh; Wali, Kashi (2009), "Marathi", London Oriental and African language library, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 13: 11,139, ISBN 978-90-272-3813-9

- Dossal, Mariam; Maloni, Ruby (1999), State intervention and popular response: western India in the nineteenth century, Popular Prakashan, p. 11, ISBN 978-81-7154-855-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Dr. Ambedkar Mission (2010), Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: Short life History, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Duff, James Grant (1863), History of the Mahrattas, I, p. 8, ISBN 978-1-4212-3360-4, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Eaton, Richard Maxwell (2005), A social history of the Deccan, 1300–1761: eight Indian lives, Volume 1, p. 192, ISBN 978-0-521-25484-7, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Enthoven, R. E (1920), The tribes and castes of Bombay, I, pp. 244–245, ISBN 978-81-206-0630-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Express News Service (2009), This Gudi Padwa, plant a neem and reap its benefits, retrieved 12 December 2009

- Farquhar, J. N (2008), The Crown of Hinduism, READ BOOKS, ISBN 978-1-4437-2397-8, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Fernandes, Braz A. (1941), Annual Bibliography Of Indian History And Indology, IV, Bombay Historical Society., OCLC 32489, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Gaikwad, Sonali; Kashyap, V. K., Molecular insight into the genesis of ranked caste populations of western India (PDF), retrieved 10 October 2010

- Ghosal, S. (2004), Kumar Suresh Singh, ed., People of India: Maharashtra, part: One, xxx, Anthropological Survey of India, pp. 478?480, ISBN 978-81-7991-100-6, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Gokhale, Sandhya (2008), The Chitpavans: social ascendancy of a creative minority in Maharashtra, 1818–1918, ISBN 978-81-8290-132-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Goonatilake, Susantha (1998), Toward a global science: mining civilizational knowledge, p. 134, ISBN 978-0-253-33388-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Government of Maharashtra (1962), Ratnagiri District Gazetteer, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Government of Maharashtra (1963), Satara District Gazetteer, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Government of Maharashtra (1969), The Gazetteers Department of Sangli, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Government of Maharashtra (1974), Wardha District Gazetteer, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Government of Maharashtra (1977), Solapur District Gazetteer, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Grimbly, Shona (2000), Grimbly, Shona, ed., Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-57958-281-4, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Gujarat (India) (1984), Gujarat State Gazetteers: Vadodara, Directorate of Govt. Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State, pp. 171–174, 183, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Haque, T.; Sirohi, A. S. (1986), Agrarian Reforms and Institutional Changes in India, Concept Publishing Company, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-81-7022-078-7, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Hassan, Syed Siraj ul (1920), The Castes and Tribes of H. E. H. The Nizam's Dominions, I, Bombay, The Times Press, p. 118, ISBN 978-81-206-0488-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Holloman, Regina E.; Aruti︠u︡nov, Sergeĭ Aleksandrovich (1978), "Ethnic Relations", Perspectives on ethnicity, 9, Mouton, ISBN 978-90-279-7690-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Jñānadeva (1981), Amrutanubhav, Ajay Prakashan, p. 5, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005), Dr. Ambedkar and untouchability: fighting the Indian caste system, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13602-0, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Johnson, Gordon (1970), S. N. Mukherjee; Edmund Leach, eds., Elites in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-10765-5, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Johnson, Gordon (2005), Provincial Politics and Indian Nationalism: Bombay and the Indian National Congress 1880?1915, Volume 14 of Cambridge South Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press, p. 55, ISBN 978-0-521-61965-3, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Karnataka (India); Abhishankar, K; Kāmat, S. (1990), Karnataka State Gazetteer: Uttara Kannada, Gazetteer of India, Printed by the Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Govt. Press, LCCN 76929567

- Karve, Irawati Karmarkar (1968), "Maharashtra - Land and Its People", Maharashtra State gazetteers - General series, 60, Government of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Karve, Irawati; Malhotra, K. C (April–June 1968), "A Biological Comparison of Eight Endogamous Groups of the Same Rank", Current Anthropology, 9 (2/3): 109, doi:10.1086/200976, JSTOR 2740725

- Katakam, Anupama (17–30 January 2004), Politics of vandalism, 21 (2), Chennai, India: Frontline, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Kher, Appaji Kashinath (1895), A higher Anglo-Marathi grammar, pp. 446–454, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Kulkarnee, Narayan H. (1975), Chhatrapati Shivaji, architect of freedom: an anthology, Chhatrapati Shivaji Smarak Samiti, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Kumar, Ravinder (2004), Western India in the Nineteenth Century: A Study in the Social History of the Maharashtra, Routledge, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-415-33048-0, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Kunte, B.G. (1972), Maharashtra State Gazetteers, Volume 8 - History Part II, Medieval Period, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai, retrieved 9 September 2015

- Lamb, Ramdas (2002), Rapt in the name: the Ramnamis, Ramnam, and untouchable religion in Central India, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-5385-8, LCCN 2002070695

- Leach, Edmund; Mukherjee, S. N (1970), Elites in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-10765-5, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Lele, J. K.; Singh, R. (1989), Language and society, E. J. Brill, Netherlands, p. 38, ISBN 978-90-04-08789-7, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Levinson, David (1992), Encyclopedia of World Cultures: South Asia, 3, G.K. Hall, p. 68, ISBN 978-0-8161-1812-0, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Madhava Rao, P. Setu, ed. (1962) [1880], "The People and their Culture - Entertainments", Maharashtra State gazetteers, Ratnagiri District, (revised edition), Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 September 2015

- Mandavdhare, S. M (1989), Caste and land relations in India: a study of Marathwada, Uppal Pub. House, p. 39, ISBN 978-81-85024-50-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Mastana, S. S; Papiha, S. S (1994), Genetic structure and microdifferentiation among four endogamous groups of Maharashtra, Western India, Annals of Human biology, 21 (3), pp. 241–262

- Michael, S. M (2007), Dalits in Modern India: Vision and Values, ISBN 978-0-7619-3571-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Misra, Satish (4 May 2006), "Obituary", Fighter to the core, Tribune News Service, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Mitra, Subrata Kumar (2006), The puzzle of India's governance: culture, context and comparative theory, 3, Routledge, p. 129, ISBN 978-0-415-34861-4, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Mohanty, Manoranjan (2004), Class, caste, gender Volume 5 of Readings in Indian government and politics, SAGE, p. 161, ISBN 978-0-7619-9643-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1989), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 174–175, ISBN 978-81-208-0423-4, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Nagi, B. S (1993), Child marriage in India: a study of its differential patterns in Rajasthan, Mittal Publications, pp. 6–9, ISBN 978-81-7099-460-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Naik, Gregory (2000), Understanding our fellow pilgrims, Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, p. 66, ISBN 978-81-87886-10-5, retrieved 10 October 2010

- NasikChitpavan.org (2010), Customs and Traditions, retrieved 18 December 2010

- Nemāḍe, Bhalacandra (1990), The Influence of English on Marathi: a sociolinguistic and stylistic study, Rajhauns Vitaran, pp. 101, 139, ISBN 978-81-85339-78-8, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Nubile, Clara (2003), The danger of gender: caste, class and gender in contemporary Indian women's writing, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-402-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Oldenberg, Hermann (1998), Die Religion Des Veda, Wein, p. 158, ISBN 978-3-534-05054-3, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Palsokar, R.D.; Rabi Reddy, T. (1995), Bajirao I: an outstanding cavalry general, Reliance Publishing House, ISBN 9788185972947, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Pandey, Ravi Narayan (2007), Encyclopaedia of Indian literature, 1, Anmol Publications, p. 19, ISBN 978-81-261-3118-1

- Paswan, Sanjay (2003), Encyclopaedia of Dalits in India: Human rights : problems and perspectives, pp. 97–110, 159–161, ISBN 978-81-7835-129-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Patterson, Maureen (2007), Bernard S. Cohn, Milton Singer, ed., Structure and Change in Indian Society, p. 398, ISBN 978-0-202-36138-3

- Pillai, S. Devadas (1997), Indian sociology through Ghurye, a dictionary, Popular Prakashan, p. 38, ISBN 978-81-7154-807-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Prakash, Om (2003), Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement, Anmol publications, p. 115, ISBN 978-81-261-0938-8, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Prasad, Amar Nath (2007), Dalit Literature, pp. 10–12, ISBN 978-81-7625-817-3, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Prasad, Rajendra (2007), India Divided, Hind Kitabs, ISBN 978-1-4067-1178-3, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Prasad, Ram Chandra (1997), The Upanayana: the Hindu ceremonies of the sacred thread, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 156–158, ISBN 978-81-208-1240-6, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Press Trust of India (28 February 2000), State assures new team to manage Pandharpur temple, Press Trust of India, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Rajagopal, Balakrishnan (18 August 2007), The caste system – India's apartheid?, Chennai, India: The Hindu, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Ranade, Mahadev Govind (1900), Rise of the Maráthá power, Punalekar & co, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (1963) [1937], "Chapter XIV - The Rise of the Maratha Empire", in Wolseley Haig, Richard Burn, The Cambridge History of India, Vol. IV - The Mughul Period, S. Chand, New Delhi, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Ray, Raka (2000), Fields of protest: women's movements in India, Zubaan, ISBN 978-81-86706-23-7, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Suryanarayana, M. (2002), Reddy, P. Sudhakar; Gangadharam, V., eds., Indian society: continuity, change, and development, in honour of Prof. M. Suryanarayana, Commonwealth Publishers, ISBN 978-81-7169-693-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Rinehart, Robin (2004), Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Risley, Herbert Hope; Gait, E.A (1903), Report on the Census of India, 1901, Calcutta, Superintendent of Government Printing, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Rivers, W. H. R; Ridgeway, Sir William (1907), The Marriage of Cousins in India, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- Saraf, Manasi (2004), Pleasures of the Paithani, Indian Express, Pune Newsline, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1946), New history of the Marathas: Sunset over Maharashtra (1772–1848), Phoenix Publications, p. 254, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1920), Shivaji and his times, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Seal, Anil (1971), The Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century (Political change in modern South Asia), pp. 74, 78, ISBN 978-0-521-09652-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Śejavalakara, Tryambaka Śaṅkara (1946), Panipat: 1761, Volume 1 of Deccan College monograph series, Poona Deccan College of Post-graduate and Research Institute (India) Volume 1 of Deccan College dissertation series, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997), Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures, Springer, p. 475, ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Sen, Ronojoy (15 May 2010), Same-gotra marriage legal, court had ruled 65 years ago, TNN, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Sen, Ronojoy (2010), Same-gotra marriages okayed in 1945, TNN

- Sharma, Arvind (2002), Modern Hindu thought: the essential texts, Oxford University Press, p. 137, ISBN 978-0-19-565315-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Sharma, S.P.; Gupta, S. (2006), Fairs and festivals of India, Pustak Mahal, ISBN 978-81-223-0951-5

- Shrivastav, P. N. (1971), Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Indore, Bhopal Government Central Press, retrieved 21 February 2011

- Śinde, J. R (1985), Dynamics of cultural revolution: 19th century Maharashtra, p. 16, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Singh, K.S; Bhanu, B.V; Anthropological Survey of India (2004), Maharashtra, People of India: States series (pt. 1), Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7991-100-6

- Srinivas, M. N (2007), "Mobility in the caste system", in Cohn, Bernard S; Singer, Milton, Structure and Change in Indian Society, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 978-0-202-36138-3, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Srinivasa-Raghavan, T.C.A (22 July 2009), Caste, cost and cause, The Hindu Business Line, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Swami, Praveen; Bavadam, Lyla (1999), Exit Manohar Joshi, Volume 16 (No. 04), The Hindu, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Swamy, Rohan (21 October 2008), Konddeo statue: Sambhaji Brigade renews threat, The Indian Express, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Thapan, Anita Raina (1997), Understanding Ganapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult, New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, p. 226, ISBN 978-81-7304-195-2, retrieved 10 October 2010

- The Economist (10 June 2010), Caste in doubt: The perilous arithmetic of positive discrimination, The Economist, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Unknown (1951), Anthropometric measurements of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Velkar, Dr. Pratap M. B. (2010), Pathare Prabhuncha Itihaas, Sau Meghana P. Rane, Mr. Tejas P. Rane& Mr. Amit P. Kothar‚, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Vinayak, M (15 January 2000), Struggle for survival, Chennai, India: The Hindu, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Walunjkar, Dr. T. N, "VII", Maharashtra: Land and its people (PDF), State of Maharashtra, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Wilson, John (1877), Indian caste, 1–2, Times of India office, ISBN 978-0-524-09449-5, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Zelliot, Eleanor (1981), Jayant Lele, ed., Tradition and modernity in Bhakti movements, pp. 136–142, ISBN 978-90-04-06370-9, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Zelliot, Eleanor; Berntsen, Maxine (1988), The Experience of Hinduism: essays on religion in Maharashtra, SUNY Press, pp. 55–56, ISBN 978-0-88706-664-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

- Zelliot, Eleanor; Berntsen, Maxine (1988), The Experience of Hinduism: essays on religion in Maharashtra, SUNY Press, p. 176, ISBN 978-0-88706-664-1, retrieved 10 October 2010

Further reading

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (February 1956), "Elite groups in a South Indian district: 1788–1858", The Journal of Asian Studies, 24 (2): 261–281, doi:10.2307/2050565, JSTOR 2050565

External links

-

Media related to Brahmins at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brahmins at Wikimedia Commons - Sacred texts: Hinduism

- Government of Maharashtra Official Website