Free trade

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

Free trade is a policy followed by some international markets in which countries' governments do not restrict imports from, or exports to, other countries. Free trade is exemplified by the European Economic Area and the North American Free Trade Agreement, which have established open markets. Most nations are today members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) multilateral trade agreements. However, most governments still impose some protectionist policies that are intended to support local employment, such as applying tariffs to imports or subsidies to exports. Governments may also restrict free trade to limit exports of natural resources. Other barriers that may hinder trade include import quotas, taxes, and non-tariff barriers, such as regulatory legislation.

Features of free trade

Free trade policies generally promote the following features:

- Trade of goods without taxes (including tariffs) or other trade barriers (e.g., quotas on imports or subsidies for producers)

- Trade in services without taxes or other trade barriers

- The absence of "trade-distorting" policies (such as taxes, subsidies, regulations, or laws) that give some firms, households, or factors of production an advantage over others

- Unregulated access to markets

- Unregulated access to market information

- Inability of firms to distort markets through government-imposed monopoly or oligopoly power

- Trade agreements which encourage free trade.

Economics of free trade

Economic models

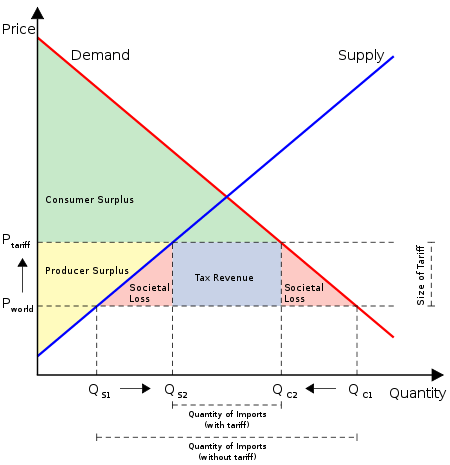

Two simple ways to understand the proposed benefits of free trade are through David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage and by analyzing the impact of a tariff or import quota. An economic analysis using the law of supply and demand and the economic effects of a tax can be used to show the theoretical benefits and disadvantages of free trade.[1][2]

Most economists would recommend that even developing nations should set their tariff rates quite low, but the economist Ha-Joon Chang, a proponent of industrial policy, believes higher levels may be justified in developing nations because the productivity gap between them and developed nations today is much higher than what developed nations faced when they were at a similar level of technological development. Underdeveloped nations today, Chang believes, are weak players in a much more competitive system.[3][4] Counterarguments to Chang's point of view are that the developing countries are able to adopt technologies from abroad, whereas developed nations had to create new technologies themselves, and that developing countries can sell to export markets far richer than any that existed in the 19th century.

If the chief justification for a tariff is to stimulate infant industries, it must be high enough to allow domestic manufactured goods to compete with imported goods in order to be successful. This theory, known as import substitution industrialization, is largely considered ineffective for currently developing nations.[3]

The economics of tariffs

The chart at the right analyzes the effect of the imposition of an import tariff on some imaginary good. Prior to the tariff, the price of the good in the world market (and hence in the domestic market) is Pworld. The tariff increases the domestic price to Ptariff. The higher price causes domestic production to increase from QS1 to QS2 and causes domestic consumption to decline from QC1 to QC2.[5][6]

This has three main effects on societal welfare. Consumers are made worse off because the consumer surplus (green region) becomes smaller. Producers are better off because the producer surplus (yellow region) is made larger. The government also has additional tax revenue (blue region). However, the loss to consumers is greater than the gains by producers and the government. The magnitude of this societal loss is shown by the two pink triangles. Removing the tariff and having free trade would be a net gain for society.[5][6]

An almost identical analysis of this tariff from the perspective of a net producing country yields parallel results. From that country's perspective, the tariff leaves producers worse off and consumers better off, but the net loss to producers is larger than the benefit to consumers (there is no tax revenue in this case because the country being analyzed is not collecting the tariff). Under similar analysis, export tariffs, import quotas, and export quotas all yield nearly identical results.[1]

Sometimes consumers are better off and producers worse off, and sometimes consumers are worse off and producers are better off, but the imposition of trade restrictions causes a net loss to society because the losses from trade restrictions are larger than the gains from trade restrictions. Free trade creates winners and losers, but theory and empirical evidence show that the size of the winnings from free trade are larger than the losses.[1]

Trade diversion

According to mainstream economic theory, the selective application of free trade agreements to some countries and tariffs on others can lead to economic inefficiency through the process of trade diversion. It is economically efficient for a good to be produced by the country which is the lowest cost producer, but this does not always take place if a high cost producer has a free trade agreement while the low cost producer faces a high tariff. Applying free trade to the high cost producer (and not the low cost producer as well) can lead to trade diversion and a net economic loss. This is why many economists place such high importance on negotiations for global tariff reductions, such as the Doha Round.[1]

Opinion of economists

The literature analysing the economics of free trade is extremely rich with extensive work having been done on the theoretical and empirical effects. Though it creates winners and losers, the broad consensus among economists is that free trade is a large and unambiguous net gain for society.[7][8] In a 2006 survey of American economists (83 responders), "87.5% agree that the U.S. should eliminate remaining tariffs and other barriers to trade" and "90.1% disagree with the suggestion that the U.S. should restrict employers from outsourcing work to foreign countries."[9]

Quoting Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw, "Few propositions command as much consensus among professional economists as that open world trade increases economic growth and raises living standards."[10] In a survey of leading economists, none disagreed with the notion that "freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment."[11]

Most economists would agree that although increasing returns to scale might mean that certain industry could settle in a geographical area without any strong economic reason derived from comparative advantage, this is not a reason to argue against free trade because the absolute level of output enjoyed by both "winner" and "loser" will increase with the "winner" gaining more than the "loser" but both gaining more than before in an absolute level.

History

Early era

The notion of a free trade system encompassing multiple sovereign states originated in a rudimentary form in 16th century Imperial Spain.[12] American jurist Arthur Nussbaum noted that Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria was "the first to set forth the notions (though not the terms) of freedom of commerce and freedom of the seas."[13] Vitoria made the case under principles of jus gentium.[13] However, it was two early British economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo who later developed the idea of free trade into its modern and recognizable form.

Economists who advocated free trade believed trade was the reason why certain civilizations prospered economically. Adam Smith, for example, pointed to increased trading as being the reason for the flourishing of not just Mediterranean cultures such as Egypt, Greece, and Rome, but also of Bengal (East India) and China. The great prosperity of the Netherlands after throwing off Spanish Imperial rule and pursuing a policy of free trade[14] made the free trade/mercantilist dispute the most important question in economics for centuries. Free trade policies have battled with mercantilist, protectionist, isolationist, communist, populist, and other policies over the centuries.

Trade in colonial America was regulated by the British mercantile system through the Acts of Trade and Navigation. Until the 1760s, few colonists openly advocated for free trade, in part because regulations were not strictly enforced—New England was famous for smuggling—but also because colonial merchants did not want to compete with foreign goods and shipping. According to historian Oliver Dickerson, a desire for free trade was not one of the causes of the American Revolution. "The idea that the basic mercantile practices of the eighteenth century were wrong," wrote Dickerson, "was not a part of the thinking of the Revolutionary leaders".[15]

Free trade came to what would become the United States as a result of American Revolutionary War, when the British Parliament issued the Prohibitory Act, blockading colonial ports. The Continental Congress responded by effectively declaring economic independence, opening American ports to foreign trade on April 6, 1776. According to historian John W. Tyler, "Free trade had been forced on the Americans, like it or not."[16]

The 1st U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, advocated tariffs to help protect infant industries in his "Report on Manufactures." For the most part, the "Jeffersonians" strongly opposed it. In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name "American System." The opposition Democratic Party contested several elections throughout the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s in part over the issue of the tariff and protection of industry.[17]

In Britain, free trade became a central principle practiced by the 1840s. Under the Treaty of Nanking, China opened five treaty ports to world trade in 1843. The first free trade agreement, the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty, was put in place in 1860 between the United Kingdom and France, which led to successive agreements between other countries in Europe.[18]

In the U.S., the Democratic Party favored moderate tariffs used for government revenue only, while the Whigs favored higher protective tariffs to protect favored industries. The economist Henry Charles Carey became a leading proponent of the "American System" of economics. This mercantilist "American System" was opposed by the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan.

The fledgling Republican Party led by Abraham Lincoln, who called himself a "Henry Clay tariff Whig", strongly opposed free trade and implemented a 44-percent tariff during the Civil War—in part to pay for railroad subsidies and for the war effort, and to protect favored industries.[19] William McKinley (later to become President of the United States) stated the stance of the Republican Party (which won every election for President from 1868 until 1912, except the two non-consecutive terms of Grover Cleveland) as thus:

Under free trade the trader is the master and the producer the slave. Protection is but the law of nature, the law of self-preservation, of self-development, of securing the highest and best destiny of the race of man. [It is said] that protection is immoral…. Why, if protection builds up and elevates 63,000,000 [the U.S. population] of people, the influence of those 63,000,000 of people elevates the rest of the world. We cannot take a step in the pathway of progress without benefitting mankind everywhere. Well, they say, 'Buy where you can buy the cheapest'…. Of course, that applies to labor as to everything else. Let me give you a maxim that is a thousand times better than that, and it is the protection maxim: 'Buy where you can pay the easiest.' And that spot of earth is where labor wins its highest rewards.[20]

Many classical liberals, especially in 19th and early 20th century Britain (e.g., John Stuart Mill) and in the United States for much of the 20th century (e.g., Cordell Hull), believed that free trade promoted peace. Woodrow Wilson included free-trade rhetoric in his "Fourteen Points" speech of 1918:

The program of the world's peace, therefore, is our program; and that program, the only possible program, all we see it, is this: [...]3. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.[21]

During the interwar period, economic protectionism took hold in the United States, most famously in the form of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which is credited by economists with the prolonging and worldwide propagation of the Great Depression.[22]:33 From 1934, trade liberalization began to take place through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. Economic historians like Paul Bairoch and many economists from Paul Krugman[23][24] on the left to Milton Friedman[25] on the right say that America’s Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 didn't cause the Great Depression.

The British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) grew up with a belief in free trade; this underpinned his criticism of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 for the damage it did to the interdependent European economy. After a brief flirtation with protectionism in the early 1930s, he came again to favour free trade so long as it was combined with internationally coordinated domestic economic policies to promote high levels of employment, and international economic institutions that meant that the interests of countries were not pitted against each other. In these circumstances, "the wisdom of Adam Smith" again applied, he said.. In "National Self-Sufficiency" The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933),[26] he explains why he no longer believes in free trade. And before his death, at the UN's Bretton Woods conference in 1944, he put forward an idea for a new system.[27] The nations with a surplus would have a powerful incentive to get rid of it. In doing so, they would automatically clear other nations' deficits. This system was against free trade.

In Kicking Away the Ladder, development economist Ha-Joon Chang reviews the history of free trade policies and economic growth, and notes that many of the now-industrialized countries had significant barriers to trade throughout their history. The United States and Britain, sometimes considered the homes of free trade policy, employed protectionism to varying degrees at all times. Britain abolished the Corn Laws, which restricted import of grain, in 1846 in response to domestic pressures, and it reduced protectionism for manufactures in the mid 19th century, when its technological advantage was at its height, but tariffs on manufactured products had returned to 23% by 1950. The United States maintained weighted average tariffs on manufactured products of approximately 40–50% up until the 1950s, augmented by the natural protectionism of high transportation costs in the 19th century.[28] The most consistent practitioners of free trade have been Switzerland, the Netherlands, and to a lesser degree Belgium.[29] Chang describes the export-oriented industrialization policies of the Four Asian Tigers as "far more sophisticated and fine-tuned than their historical equivalents".[30]

Some degree of protectionism is nevertheless the norm throughout the world. Most developed nations maintain controversial agricultural tariffs. From 1820 to 1980, the average tariffs on manufactures in twelve industrial countries ranged from 11 to 32%. In the developing world, average tariffs on manufactured goods are approximately 34%.[31]

Post-World War II

Since the end of World War II, in part due to industrial size and the onset of the Cold War, the United States has often been a proponent of reduced tariff-barriers and free trade. The U.S. helped establish the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later the World Trade Organization (WTO); although it had rejected an earlier version in the 1950s (International Trade Organization or ITO).[32] Since the 1970s, U.S. governments have negotiated managed-trade agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the 1990s, the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) in 2006, and a number of bilateral agreements (such as with Jordan).

In Europe, six countries formed the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 which became the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1958. Two core objectives of the EEC were the development of a common market, subsequently renamed the single market, and establishing a customs union between its member states. After expanding its membership, the EEC became the European Union (EU) in 1993. The European Union, now the world's largest single market,[33] has concluded free trade agreements with many countries around the world.[34]

Current status

Most countries in the world are members of the World Trade Organization,[35] which limits in certain ways but does not eliminate tariffs and other trade barriers. Most countries are also members of regional free trade areas that lower trade barriers among participating countries. The EU and the US are negotiating a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Led by the U.S., twelve countries that have borders on the Pacific Ocean are currently in private negotiations[36] around the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is being touted by the negotiating countries as a free trade policy.[37]

Degree of free trade policies

The Enabling Trade Index measures the factors, policies and services that facilitate the trade in goods across borders and to destination. It is made up of four sub-indexes: market access; border administration; transport and communications infrastructure; and business environment. The top 20 countries and areas are:[38]

-

Singapore 6.1

Singapore 6.1 -

Hong Kong 6.0

Hong Kong 6.0 -

Netherlands 6.0

Netherlands 6.0 -

United Kingdom 6.0

United Kingdom 6.0 -

Japan 5.9

Japan 5.9 -

Germany 5.9

Germany 5.9 -

Republic of Korea 5.8

Republic of Korea 5.8 -

United States 5.8

United States 5.8 -

France 5.8

France 5.8 -

United Arab Emirates 5.8

United Arab Emirates 5.8 -

Switzerland 5.7

Switzerland 5.7 -

Spain 5.6

Spain 5.6 -

Luxembourg 5.6

Luxembourg 5.6 -

Finland 5.5

Finland 5.5 -

Taiwan 5.5

Taiwan 5.5 -

Denmark 5.5

Denmark 5.5 -

Sweden 5.5

Sweden 5.5 -

.svg.png) Belgium 5.4

Belgium 5.4 -

Austria 5.3

Austria 5.3 -

Australia 5.2

Australia 5.2

Opposition

The relative costs, benefits and beneficiaries of free trade are debated by academics, governments and interest groups.

Arguments for protectionism fall into the economic category (trade hurts the economy) or the moral category (the effects of trade might help the economy, but have ill effects in other areas); a general argument against free trade is that it is colonialism or imperialism in disguise. The moral category is wide, including concerns of destroying infant industries and undermining long-run economic development, income inequality, environmental degradation, supporting child labor and sweatshops, race to the bottom, wage slavery, accentuating poverty in poor countries, harming national defense, and forcing cultural change.[39]

Economic arguments against free trade criticize the assumptions or conclusions of economic theories. Sociopolitical arguments against free trade cite social and political effects that economic arguments do not capture, such as political stability, national security, human rights and environmental protection.

Free trade is often opposed by domestic industries that would have their profits and market share reduced by lower prices for imported goods.[40][41] For example, if United States tariffs on imported sugar were reduced, U.S. sugar producers would receive lower prices and profits, while U.S. sugar consumers would spend less for the same amount of sugar because of those same lower prices. The economic theory of David Ricardo holds that consumers would necessarily gain more than producers would lose.[42][43] Since each of those few domestic sugar producers would lose a lot while each of a great number of consumers would gain only a little, domestic producers are more likely to mobilize against the lifting of tariffs.[41] More generally, producers often favor domestic subsidies and tariffs on imports in their home countries, while objecting to subsidies and tariffs in their export markets.

Socialists frequently oppose free trade on the ground that it allows maximum exploitation of workers by capital. For example, Karl Marx wrote in The Communist Manifesto, "The bourgeoisie... has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – free trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation." Nonetheless, Marx did favor free trade—solely because he felt that it would hasten the social revolution.[46]

"Free trade" is opposed by many anti-globalization groups, based on their assertion that free trade agreements generally do not increase the economic freedom of the poor or the working class, and frequently make them poorer. Where the foreign supplier allows de facto exploitation of labor, domestic free-labor is unfairly forced to compete with the foreign exploited labor, and thus the domestic "working class would gradually be forced down to the level of helotry."[47] To this extent, free trade is seen as an end-run around workers' rights and laws that protect individual liberty.

It is important to distinguish between arguments against free trade theory, and free trade agreements as applied. Some opponents of NAFTA see the agreement as being materially harmful to the common people, but some of the arguments are actually against the particulars of government-managed trade, rather than against free trade per se. For example, it is argued[48] that it would be wrong to let subsidized corn from the U.S. into Mexico freely under NAFTA at prices well below production cost (dumping) because of its ruinous effects to Mexican farmers. Of course, such subsidies violate free trade theory, so this argument is not actually against the principle of free trade, but rather its selective implementation.

Research shows that support for trade restrictions is highest among respondents with the lowest levels of education.[49] The authors find "that the impact of education on how voters' think about trade and globalization has more to do with exposure to economic ideas and information about the aggregate and varied effects of these economic phenomena, than it does with individual calculations about how trade affects personal income or job security. This is not to say that the latter types of calculations are not important in shaping individuals' views of trade—just that they are not being manifest in the simple association between education and support for trade openness."[49]

Research suggests that attitudes towards free trade do not necessarily reflect individuals' self-interests.[50][51]

Colonialism

It has long been argued that free trade is a form of colonialism or imperialism, a position taken by various proponents of economic nationalism and the school of mercantilism. In the 19th century these criticized British calls for free trade as cover for British Empire, notably in the works of American Henry Clay, architect of the American System[52] and by German American economist Friedrich List.[53]

More recently, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa has denounced the "sophistry of free trade" in an introduction he wrote for a book titled The Hidden Face of Free Trade Accords, written in part by Correa's current Energy Minister Alberto Acosta. Citing as his source the book Kicking Away the Ladder, written by Ha-Joon Chang, Correa identified the difference between an "American system" opposed to a "British System" of free trade. The latter, he says, was explicitly viewed by the Americans as "part of the British imperialist system." According to Correa, Chang showed that it was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, and not Friedrich List, who was the first to present a systematic argument defending industrial protectionism.

Alternatives

The following alternatives for free trade have been proposed: balanced trade, fair trade, protectionism, industrial policy.

In literature

The value of free trade was first observed and documented by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, in 1776.[54] He wrote,

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy.... If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.[55]

This statement uses the concept of absolute advantage to present an argument in opposition to mercantilism, the dominant view surrounding trade at the time, which held that a country should aim to export more than it imports, and thus amass wealth.[56] Instead, Smith argues, countries could gain from each producing exclusively the good(s) in which they are most suited to, trading between each other as required for the purposes of consumption. In this vein, it is not the value of exports relative to that of imports that is important, but the value of the goods produced by a nation. The concept of absolute advantage however does not address a situation where a country has no advantage in the production of a particular good or type of good.[57]

This theoretical shortcoming was addressed by the theory of comparative advantage. Generally attributed to David Ricardo who expanded on it in his 1817 book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation,[58] it makes a case for free trade based not on absolute advantage in production of a good, but on the relative opportunity costs of production. A country should specialize in whatever good it can produce at the lowest cost, trading this good to buy other goods it requires for consumption. This allows for countries to benefit from trade even when they do not have an absolute advantage in any area of production. While their gains from trade might not be equal to those of a country more productive in all goods, they will still be better off economically from trade than they would be under a state of autarky. [59][60]

Exceptionally, Henry George's 1886 book Protection or Free Trade was read out loud in full into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen.[61][62] Tyler Cowen wrote that 'Protection or Free Trade "remains perhaps the best-argued tract on free trade to this day."[63] George discusses the subject in particular with respect to the interests of labor. Although George is very critical towards protectionism:

We all hear with interest and pleasure of improvements in transportation by water or land; we are all disposed to regard the opening of canals, the building of railways, the deepening of harbors, the improvement of steamships as beneficial. But if such things are beneficial, how can tariffs be beneficial? The effect of such things is to lessen the cost of transporting commodities; the effect of tariffs is to increase it. If the protective theory be true, every improvement that cheapens the carriage of goods between country and country is an injury to mankind unless tariffs be commensurately increased.[64]

George considers the general free trade argument 'inadequate'. He argues that the removal of protective tariffs alone is never be sufficient to improve the situation of the working class, unless accompanied by a shift towards land value tax.

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Free trade |

Concepts/topics:

- Free trade area

- Free trade zone

- Freedom of choice

- International free trade agreement

- Trade war

- Trade war over genetically modified food

- Offshore outsourcing

- Offshoring

- Borderless Selling

- Trade bloc

- Economic globalization

- Trade Adjustment Assistance

Trade organizations:

References

- 1 2 3 4 Steven E. Landsburg. Price Theory and Applications, Sixth Edition, Chapter 8

- ↑ Thom Hartmann, Unequal Protection, Second Edition, Chapter 20. p. 255

- 1 2 Pugel (2007), International Economics, pp. 311–312

- ↑ Chang, Ha-Joon, Kicking Away the Ladder: Good Policies and Good Institutions in Historical Perspective

- 1 2 Alan C. Stockman, Introduction to Economics, Second Edition, Chapter 9

- 1 2 N. Gregory Mankiw, Macroeconomics, Fifth Edition, Chapter 7

- ↑ Fuller, Dan; Geide-Stevenson, Doris (Fall 2003). "Consensus Among Economists: Revisited" (PDF). Journal of Economic Review. 34 (4): 369–387. doi:10.1080/00220480309595230. (registration required)

- ↑ Friedman, Milton. "The Case for Free Trade". Hoover Digest. 1997 (4).

- ↑ Whaples, Robert (2006). "Do Economists Agree on Anything? Yes!". The Economists' Voice. 3 (9). doi:10.2202/1553-3832.1156.

- ↑ Mankiw, Gregory (2006-05-07). "Outsourcing Redux". Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ↑ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ↑ Giovanni Arrighi (1994). The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. Verso. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-85984-015-3.

- 1 2 Arthur Nussbaum (1947). A concise history of the law of nations. Macmillan Co. p. 62.

- ↑ Appleby, Joyce (2010). The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Dickerson, The Navigation Acts and the American Revolution, p. 140.

- ↑ Tyler, Smugglers & Patriots, p. 238.

- ↑ Larry Schweikart, What Would the Founders Say? (New York: Sentinel, 2011), pp. 106–124.

- ↑ International Monetary Fund Research Dept. (1997). World Economic Outlook, May 1997: Globalization: Opportunities and Challenges. International Monetary Fund. p. 113. ISBN 9781455278886.

- ↑ Lind, Matthew. "Free Trade Fallacy". Prospect. Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ William McKinley speech, October 4, 1892 in Boston, MA William McKinley Papers (Library of Congress)

- ↑ Fourteen Points

- ↑ Eun, Cheol S.; Resnick, Bruce G. (2011). International Financial Management, 6th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-803465-7.

- ↑ http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/21/hoot-smalley/?_r=0 Paul Krugman

- ↑ http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/03/04/the-mitt-hawley-fallacy/

- ↑ https://books.google.fr/books?id=MIDsnT3Ze0YC&pg=PA116&lpg=PA116&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ http://www.india-seminar.com/2009/601/601_david_singh_grewali.htm

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/nov/18/lord-keynes-international-monetary-fund

- ↑ Chang (2003), Kicking Away the Ladder, p. 17

- ↑ Chang (2003), Kicking Away the Ladder, p. 59

- ↑ Chang (2003), Kicking Away the Ladder, p. 50

- ↑ Chang (2003), Kicking Away the Ladder, p. 66

- ↑ http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/pera9707.pdf

- ↑ "EU position in world trade". European Commission. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Agreements". European Commission. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Members and Observers". World Trade Organisation. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "Everything You Need To Know About The Trans-Pacific Partnership". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Trans-Pacific Partnership". U.S. Trade Representative. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ World Economic Forum. "Rankings: Global Enabling Trade Report 2010" (PDF).

- ↑ Boudreaux, Don Globalization, 2007

- ↑ William Baumol and Alan Blinder, Economics: Principles and Policy, p. 722.

- 1 2 Brakman, Steven; Harry Garretsen; Charles Van Marrewijk; Arjen Van Witteloostuijn (2006). Nations and Firms in the Global Economy : An Introduction to International Economics and Business. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83298-4.

- ↑ Richard L. Stroup, James D. Gwartney, Russell S. Sobel, Economics: Private and Public Choice, p. 46.

- ↑ Pugel, Thomas A. (2003). International economics. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-119875-X.

- ↑ "Earnings – National". Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ "Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product". National Income and Product Accounts Table. U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ "It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade." Marx, Karl On the Question of Free Trade Speech to the Democratic Association of Brussels at its public meeting of January 9, 1848

- ↑ Marx, Karl The Civil War in the United States, ¶ 23.

- ↑ Institute for Agricultural and Trade Policy NAFTA Truth and Consequences: Corn

- 1 2 Hainmueller, Jens; Hiscox, Michael J. (2006-04-01). "Learning to Love Globalization: Education and Individual Attitudes Toward International Trade". International Organization. 60 (02): 469–498. doi:10.1017/S0020818306060140. ISSN 1531-5088.

- ↑ Mansfield, Edward D.; Mutz, Diana C. (2009-07-01). "Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest, Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety". International Organization. 63 (03): 425–457. doi:10.1017/S0020818309090158. ISSN 1531-5088.

- ↑ "Why Don't Trade Preferences Reflect Economic Self-Interest?" (PDF).

- ↑ "Gentlemen deceive themselves. It is not free trade that they are recommending to our acceptance. It is, in effect, the British colonial system that we are invited to adopt; and, if their policy prevail, it will lead, substantially, to the recolonization of these States, under the commercial dominion of Great Britain.", "In Defense of the American System, Against the British Colonial System." 1832, Feb 2, 3, and 6, Clay, Henry (1843). "The Life and Speeches of Henry Clay". II: 23–24.

- ↑ "Had the English left everything to itself—'Laissez faire, laissez aller', as the popular economical school recommends—the [German] merchants of the Steelyard would be still carrying on their trade in London, the Belgians would be still manufacturing cloth for the English, England would have still continued to be the sheep-farm of the Hansards, just as Portugal became the vineyard of England, and has remained so till our days, owing to the stratagem of a cunning diplomatist."

- ↑ Bhagwati (2002), Free Trade Today, p. 3

- ↑ Smith, Wealth of Nations, pp. 264–265

- ↑ Pugel (2007), International Economics, p. 33

- ↑ Pugel (2007), International Economics, p. 34

- ↑ Ricardo (1817), On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Chapter 7 "On Foreign Trade"

- ↑ Bhagwati (2002), Free Trade Today, p 1

- ↑ Pugel (2007), International Economics, pp. 35–38, 40

- ↑ Weir, "A Fragile Alliance," 425–425

- ↑ Henry George, Protection or Free Trade: An Examination of the Tariff Question, with Especial Regard to the Interests of Labor(New York: 1887).

- ↑ Cowen, Tyler (May 1, 2009). "Anti-Capitalist Rerun". The American Interest. 4 (5). Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ "True Free Trade", Chapter 3, Protection or Free Trade

59. Galiani, Sebastian, Norman Schofield, and Gustavo Torrens. 2014. Factor Endowments, Democracy and Trade Policy Divergence. Journal of Public Economic Theory 16(1): 119-56.

Bibliography

- Bhagwati, Jagdish. Free Trade Today. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2002). ISBN 0-691-09156-0

- Blinder, Alan S. (2008). "Free Trade". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Chang, Ha-Joon. Kicking Away The Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press 2003. ISBN 978-1-84331-027-3.

- Dickerson, Oliver M. The Navigation Acts and the American Revolution. New York : Barnes (1963). ISBN 978-0374921620 OCLC 490386016

- Pugel, Thomas A. International Economics, 13th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin (2007). ISBN 978-0-07-352302-6

- Ricardo, David. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Library of Economics and Liberty (1999)

- Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Digireads Publishing (2009), ISBN 1-4209-3206-3

- Tyler, John W. Smugglers & Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution. Boston: Northeastern University Press (1986). ISBN 0-930350-76-6

Further reading

- Medley, George Webb (1881). England under free trade. London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.