Economy of the Republic of Ireland

|

| |

| Currency | 1 Euro = 100-cent(s)= 1.07USD |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, WTO and OECD |

| Statistics | |

| GDP |

|

| GDP rank | 41st (nominal, 2016) |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita |

|

GDP by sector | Services (70.4%), industry (28%), agriculture (1.6%) (2013 est.)[3] |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | 8.2% (consistent poverty in 2013)[5] Poverty line in 2015: €11,000/year or ~$1,000/month[6] |

| 30.0 (2014)[7] | |

Labour force |

|

Labour force by occupation | services (78%), industry (19%), agriculture (5%) (2011 est.) |

| Unemployment |

|

Average gross salary | €3,050 / $3,300, month (2016-Q2)[10] |

| €2,440 / $2,600, month (2016-Q2)[11] | |

Main industries |

List

|

| 13th[12] | |

| External | |

| Exports |

|

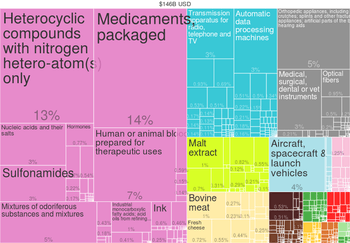

Export goods |

List

|

Main export partners |

|

| Imports |

|

Import goods |

List

|

Main import partners |

|

|

| |

Gross external debt |

|

|

| |

| Public finances | |

|

| |

|

| |

| Revenues |

|

| Expenses |

|

| Economic aid |

Donor of ODA: $585 million (2010)[16] Recipient of agricultural aid: $895 million (2010)[17] |

|

Standard & Poor's:[18] A+ (Domestic) A+ (Foreign) AAA (T&C Assessment) Outlook: Stable Moody's:[19] A3 Outlook: Positive Fitch: A Outlook: Positive | |

Foreign reserves |

|

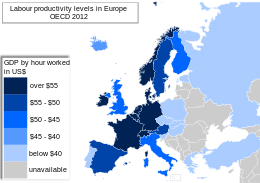

The economy of Ireland is a modern knowledge economy, focusing on services and high-tech industries and dependent on trade, industry and investment. In terms of GDP per capita, Ireland is ranked as one of the wealthiest countries in the OECD and the EU-27 at 5th in the OECD-28 rankings as of 2008.[21] In terms of GNP per capita, a better measure of national income, Ireland ranks only slightly above the OECD average, despite significant growth in recent years, at 10th in the OECD-28 rankings. GDP (national output) is significantly greater than GNP (national income) due to the repatriation of profits and royalty payments by multinational firms based in Ireland.[22]

A 2005 study by The Economist found Ireland to have the best quality of life in the world.[23] The 1995 to 2007 period of very high economic growth, with a record of posting the highest growth rates in Europe, led many to call the country the Celtic Tiger.[24] One of the keys to this economic growth was a low corporation tax, currently at 12.5% standard rate.[25]

The Irish financial crisis severely affected the economy, compounding domestic economic problems related to the collapse of the Irish property bubble. After 24 years of continuous growth at an annual level during 1984–2007,[26] Ireland first experienced a short technical recession from Q2-Q3 2007, followed by a long 2-year recession from Q1 2008 – Q4 2009.[27] In March 2008, Ireland had the highest level of household debt relative to disposable income in the developed world at 190%, causing a further slow down in private consumption, and thus also being one of the reasons for the long lasting recession.[28] The hard economic climate was reported in April 2010, even to have led to a resumed emigration.[29]

After a year with stagnant economic activity in 2010, Irish real GDP rose by 2.2% in 2011 and 0.2% in 2012, which was mainly driven by strong improvements in the export sector – while private consumption remained subdued. The economic challenges continued, however, as the prolonged European sovereign-debt crisis caused a new Irish recession starting in Q3 2012, which was still ongoing as of Q2 2013.[30] In May 2013 the European Commission's economic forecast for Ireland predicted its growth rates would return to a positive 1.1% in 2013 and 2.2% in 2014.[31] The Irish economy grew by 4.8% in 2014 and an unexpected 26.3% in 2015.

As of 2015, Ireland was ranked as the world's ninth most "economically free" economy in an index created by free-market economists from the Wall Street Journal and Heritage Foundation, the Index of Economic Freedom.

History

Since the Irish Free State

From the 1920s Ireland had high trade barriers such as high tariffs, particularly during the Economic War with Britain in the 1930s, and a policy of import substitution. During the 1950s, 400,000 people emigrated from Ireland.[32] It became increasingly clear that economic nationalism was unsustainable. While other European countries enjoyed fast growth, Ireland suffered economic stagnation.[32] The policy changes were drawn together in Economic Development, an official paper published in 1958 that advocated free trade, foreign investment, and growth rather than fiscal restraint as the prime objective of economic management.[32]

In the 1970s, the population increased by 15% and national income increased at an annual rate of about 4%. Employment increased by around 1% per year, but the state sector amounted to a large part of that. Public sector employment was a third of the total workforce by 1980. Budget deficits and public debt increased, leading to the crisis in the 1980s.[32] During the 1980s, underlying economic problems became pronounced. Middle income workers were taxed 60% of their marginal income,[33] unemployment had risen to 20%, annual overseas emigration reached over 1% of population, and public deficits reached 15% of GDP.

In 1987 Fianna Fáil reduced public spending, cut taxes, and promoted competition. Ryanair used Ireland's deregulated aviation market and helped European regulators to see benefits of competition in transport markets. Intel invested in 1989 and was followed by a number of technology companies such as Microsoft and Google. A consensus exists among all government parties about the sustained economic growth.[32] The GDP per capita in the OECD prosperity ranking rose from 21st in 1993 to 4th in 2002.[34]

Between 1985 and 2002, private sector jobs increased 59%. The economy shifted from an agriculture to a knowledge economy, focusing on services and high-tech industries. Economic growth averaged 10% from 1995 to 2000, and 7% from 2001 to 2004. Industry, which accounts for 46% of GDP and about 80% of exports, has replaced agriculture as the country's leading sector.

Celtic Tiger (1995–2007)

The economy benefited from a rise in consumer spending, construction, and business investment. Since 1987, a key part of economic policy has been Social Partnership, which is a neo-corporatist set of voluntary 'pay pacts' between the Government, employers and trade unions. The 1995 to 2000 period of high economic growth was called the "Celtic Tiger", a reference to the "tiger economies" of East Asia.[24]

GDP growth continued to be relatively robust, with a rate of about 6% in 2001, over 4% in 2004, and 4.7% in 2005. With high growth came high inflation. Prices in Dublin were considerably higher than elsewhere in the country, especially in the property market.[35] However, property prices are falling following the recent economic recession. At the end of July 2008, the annual rate of inflation was at 4.4% (as measured by the CPI) or 3.6% (as measured by the HICP)[36][37] and inflation actually dropped slightly from the previous month.

In terms of GDP per capita, Ireland is ranked as one of the wealthiest countries in the OECD and the EU-27, at 4th in the OECD-28 rankings. In terms of GNP per capita, a better measure of national income, Ireland ranks below the OECD average, despite significant growth in recent years, at 10th in the OECD-28 rankings. GDP is significantly greater than GNP (national income) due to the large number of multinational firms based in Ireland.[22] A 2005 study by The Economist found Ireland to have the best quality of life in the world.[23]

The positive reports and economic statistics masked several underlying imbalances. The construction sector, which was inherently cyclical in nature, accounted for a significant component of Ireland's GDP. A recent downturn in residential property market sentiment has highlighted the over-exposure of the Irish economy to construction, which now presents a threat to economic growth.[38][39][40] Despite several successive years of economic growth and significant improvements since 2000, Ireland's population is marginally more at risk of poverty than the EU-15 average and 6.8% of the population suffer "consistent poverty".[22][41]

Economic downturn (2008–2013)

It was the first country in the EU to officially enter a recession related to the Financial crisis 2008, as declared by the Central Statistics Office.[42] Ireland now has the second-highest level of household debt in the world (190% of household income).[43] The country's credit rating was downgraded to "AA-" by Standard & Poor's ratings agency in August 2010 due to the cost of supporting the banks, which would weaken the Government's financial flexibility over the medium term.[44] It transpired that the cost of recapitalising the banks was greater than expected at that time, and, in response to the mounting costs, the country's credit rating was again downgraded by Standard & Poor's to "A".[45][46]

The global recession has significantly impacted the Irish economy. Economic growth was 4.7% in 2007, but −1.7% in 2008 and −7.1% in 2009. In mid-2010, Ireland looked like it was about to exit recession in 2010 following growth of 0.3% in Q4 of 2009 and 2.7% in Q1 of 2010. The government forecast a 0.3% expansion.[47][48][49] However the economy experienced Q2 negative growth of −1.2%,[49] and in the fourth quarter, the GDP shrunk by 1.6%. Overall, the GDP was reduced by 1% in 2010, making it the third consecutive year of negative growth.[50] On the other hand, Ireland recorded the biggest month-on-month rise for industrial production across the eurozone in 2010, with 7.9% growth in September compared to August, followed by Estonia (3.6%) and Denmark (2.7%).[51]

The second problem, unacknowledged by management of Irish banks, the financial regulator and the Irish government,[52] is solvency. The question concerning solvency has arisen due to domestic problems in the crashing Irish property market. Irish financial institutions have substantial exposure to property developers in their loan portfolio.[53] In 2008, property developers had an over-supply of property, with much unsold as demand significantly diminished. The employment growth of the past that attracted many immigrants from Eastern Europe and propped up demand for property was replaced by rising unemployment.[54]

Irish property developers speculated billions of Euros in overvalued land parcels such as urban brownfield and greenfield sites. They also speculated in agricultural land which, in 2007, had an average value of €23,600 per acre ($32,000 per acre or €60,000 per hectare)[55] which is several multiples above the value of equivalent land in other European countries. Lending to builders and developers has grown to such an extent that it equals 28% of all bank lending, or "the approximate value of all public deposits with retail banks. Effectively, the Irish banking system has taken all its shareholders' equity, with a substantial chunk of its depositors' cash on top, and handed it over to builders and property speculators.....By comparison, just before the Japanese bubble burst in late 1989, construction and property development had grown to a little over 25 per cent of bank lending."[56]

Irish banks correctly identify a systematic risk of triggering an even more severe financial crisis in Ireland if they were to call in the loans as they fall due. The loans are subject to terms and conditions, referred to as "covenants". These covenants are being waived[57] in fear of provoking the (inevitable) bankruptcy of many property developers[58] and banks are thought to be "lending some developers further cash to pay their interest bills, which means that they are not classified as 'bad debts' by the banks".[53] Furthermore, the banks' "impairment" (bad debt) provisions are still at very low levels.[59][60] This does not appear to be consistent with the real negative changes taking place in property market fundamentals.

On 30 September 2008, the Irish Government declared a guarantee that intends to safeguard the Irish banking system. The Irish National guarantee, backed by taxpayer funds, covers "all deposits (retail, commercial, institutional and interbank), covered bonds, senior debt and dated subordinated debt".[61] In exchange for the bailout, the government did not take preferred equity stakes in the banks (which dilute shareholder value) nor did they demand that top banking executives' salaries and bonuses be capped, or that board members be replaced.[62]

Despite the Government guarantees to the banks, their shareholder value continued to decline and on 2009-01-15, the Government[63] nationalised Anglo Irish Bank, which had a market capitalisation of less than 2% of its peak in 2007. Subsequent to this, further pressure came on the other two large Irish banks, who on 2009-01-19, had share values fall[64] by between 47 and 50% in one day. As of 11 October 2008, leaked reports of possible actions by the government[65] to artificially prop up the property developers have been revealed.

In contrast, on 7 October 2008, Danske Bank wrote off a substantial sum largely due to property-related losses incurred by its Irish subsidiary – National Irish Bank.[66] The 3.18%[67] charge against the loan book of its Irish operations is the first significant write off to take place and is a modest indication of the extent of the more substantial future charges to be incurred by the over-exposed domestic banks. Asset write downs by the domestically-owned Irish banks are only now slowly beginning to take place[53]

In November 2010 the Irish government published a National Recovery plan, which aimed to restore order to the public finances and to bring its deficit in line with the EU target of 3% of economic output by 2015.[68] The plan envisaged a budget adjustment of €15 billion (€10 billion in public expenditure cuts and €5 billion in taxes) over a four-year period. This was front-loaded in 2011, when measures totalling €6 billion took place. Subsequent budgetary adjustments of €3 billion per year were put in place up to 2015, to reduce the government deficit to less than 3% of GDP. VAT would increase to 23% by 2014. A property tax was re-introduced in 2012. This was initially charged in 2012 as a flat rate on all properties and subsequently charged at a level of 0.18% of the estimated market-value of a property from 2013. Domestic water charges are to be introduced in 2015.[69][70] Expenditure cuts included reductions in public sector pay levels, reductions in the number of public sector employees through early retirement schemes, reduced social welfare payments and reduced health spending. As a result of increased taxation and decreased government spending the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) reported that the Irish government deficit had decreased from 32.5% of GDP in 2010 (a level boosted by one-off support payments to the financial sector) to 5.7% of GDP in 2013. [71] In addition Ireland's unemployment rate fell from a peak of 15.1% in February 2012 to 10.6% in December 2014.[72] The number of people in employment increased by 58,000 (3.1% increase in employment rate) in the year to September 2013. On 27 February 2014 the government launched its Action Plan for Jobs 2014, which followed similar plans initiated in 2013 and 2012.[73]

Signs of recovery (2014 onwards)

The term "Celtic Phoenix" was coined by journalist and satirist Paul Howard,[74] which has been occasionally used by some economic commentators and media outlets to describe the indicators of economic growth in some sectors in Ireland since 2014.[75][76]

In late 2013, Ireland exited an EU/ECB/IMF bailout. The Irish economy began to recover in 2014, growing by 4.8%, making Ireland the fastest growing economy in the European Union.[77] Contributing factors to growth included a recovering construction sector, quantitative easing, a weak euro, and low oil prices.[78][79] This growth helped to reduce national debt to 109% of GDP, and the budget deficit fell to 3.1% in the fourth quarter.[80]

The headline unemployment rate remained steady at 10%, though the youth unemployment rate remained higher than the EU average, at over 20%.[81][82] Emigration had continued to play a significant factor in unemployment statistics, though the emigration rate also began to fall in 2014.[83][84]

Property prices also increased in 2014, growing fastest in Dublin. This was due to a housing shortage, especially in the Dublin area. The demand for housing caused some recovery in the Irish construction and property sectors.[85] By early 2015, house price increases nationally began to outpace those in Dublin. Cork saw house prices rise by 7.2%, while Galway prices rose by 6.8%. Prices in Limerick were 6.7% higher while in Waterford there was a 4.9% increase.[86] The housing crisis resulted in over 20,000 applicants being on the social housing list in the Dublin City Council area for the first time.[87] In May 2015, the Insolvency Service of Ireland reported to the Oireactas Justice Committee that 110,000 mortgages were in arrears, and 37,000 of those are in arrears of over 720 days.[88]

On 14 October 2014, Minister for Finance Michael Noonan and Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform Brendan Howlin introduced the budget for 2015, the first in seven years to include tax cuts and spending increases.[89] The budget reversed some of the austerity measures that had been introduced over the previous six years, with increased spending and tax cuts worth just over €1bn.[90][91][92][93]

In April 2015, during a "Spring Economic Statement", Noonan and Howlin outlined the government's plans and projections up to the year 2020.[94][95] This included policy statements on expansionary budgets, deficit management plans and proposed cuts to the Universal Social Charge and other taxes.[96]

In October 2014, German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble said that Germany was "jealous" at how the Irish economy had recovered after its bailout. He also said that Ireland had made a significant contribution to the stabilisation of the euro.[97] While Taoiseach Enda Kenny praised the economic growth, and said that Ireland would seek to avoid returning to a "boom and bust" cycle, he noted that other areas of the economy remained fragile.[98][99][100] The European Commission also acknowledged the recovery and growth, but warned that any extra government revenue should be used to further reduce the national debt.[101]

Some other commentators have suggested that, depending on the Eurozone, world economic outlook as well as other internal and external factors, the growth seen in Ireland in 2014 and early 2015 may not indicate a longer-term pattern for sustainable economic improvement.[102][103][104][105] Other commentators have noted that recovery figures do not account for emigration, youth unemployment, child poverty, homelessness and other factors.[106]

On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, which was widely reported as likely having a negative impact on trade between the UK and Ireland, and the Irish economy in general.[107][108] Other commentators, for example the Financial Times, suggested that some London-based financial institutions might move operations to Dublin after Brexit.[109]

In 2016 official CSO figures indicated that the economic recovery had led to 26.3% growth in GDP in 2015 and 18.7% growth in GNP. [110] There was a suggestion that the accounting practices of multinationals (including shallow or shell companies) contributed to the figures.[111][112] Some economists described the 26.3% figure as "meaningless" and "farcical".[111][113]

Sectors

Alcoholic beverage industry

The drinks industry employs approximately 92,000 people and contributes 2 billion euro annually to the Irish economy[114] making it one of the biggest sectors. It supports jobs in agriculture, distilling and brewing. It is subdivided into 5 areas; beer (employing 1,800 people directly and 35,000 indirectly),[115] cider (supporting 5,000 jobs),[116] spirits (supporting 14,700 jobs),[117] whiskey (employing 748 people with turnover of 400 million euro)[118] and wine (employing 1,100 directly).[119]

Financial services

The financial services sector employs approximately 35,000 people and contributes 2 billion euro in taxes annually to the economy.[120] Ireland is the seventh largest provider of wholesale financial services in Europe.[120] A number of these firms are located at the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) in Dublin.

Aircraft leasing

There are 1,200 directly employed in leasing, with Irish lessors managing more than €100 billion in assets. This means that Ireland manages nearly 22% of the fleet of aircraft worldwide and a 40% share of Global fleet of leased aircraft. Ireland has 14 of the top 15 lessors by fleet size.

Engineering

The Engineering sector employs over 18,500 people and contributes approximately 4.2 billion euro annually.[121] This includes approximately 180 companies in areas such of industrial products and services, aerospace, automotive and clean tech.

Information and communications technology

The Information and communications technology (ICT) sector employs over 37,000 people and generates 35 billion annually. The top ten ICT companies are located in Ireland, with over 200 companies in total.[122] A number of these ICT companies are based at the Silicon Docks in Dublin. Google, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Amazon, eBay, PayPal and Microsoft many of which have their EMEA / Europe & Middle East headquarters in Ireland.

Software

The software sector employs approximately 24,000 people and contributes 16 billion euro to the economy. Ireland is the world's second largest exporter of software. The top 10 global technology firms have operations in Ireland including Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft. Ireland is home to over 900 software companies.[123]

Medical technologies

The Medical technology (MedTech) sector employs nearly 25,000 people and generates 9.4 billion euro annually, with over one hundred companies in the country.[124]

Pharmaceuticals

The pharmaceutical sector employs approximately 50,000 people and is responsible for 55 billion euro of exports.[125]

Exports

Exports play an important role in Ireland's economic growth. A series of significant discoveries of base metal deposits have been made, including the giant ore deposit at Tara Mine. Zinc-lead ores are also currently mined from two other underground operations in Lisheen and Galmoy. Ireland now ranks as the seventh largest producer of zinc concentrates in the world, and the twelfth largest producer of lead concentrates. The combined output from these mines make Ireland the largest zinc producer in Europe and the second largest producer of lead.[126]

Ireland is the world's most profitable country for US corporations, with a corporation tax rate of 12.5% according to the US tax journal Tax Notes.[127] The country is one of the largest exporters of pharmaceuticals, medical devices and software-related goods and services in the world.[128] Bord Gáis is responsible for the supply and distribution of natural gas, which was first brought ashore in 1976 from the Kinsale Head gas field. Electrical generation from peat consumption, as a percent of total electrical generation, was reduced from 18.8% to 6.1%, between 1990 and 2004.[129] A forecast by Sustainable Energy Ireland predicts that oil will no longer be used for electrical generation but natural gas will be dominant at 71.3% of the total share, coal at 9.2%, and renewable energy at 8.2% of the market.[129]

New sources are expected to come on stream after 2010, including the Corrib gas field and potentially the Shannon Liquefied Natural Gas terminal.[130] In its Globalization Index 2010 published in January 2011 Ernst and Young with the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Ireland second after Hong Kong. The index ranks 60 countries according to their degree of globalisation relative to their GDP.[131] While the Irish economy has significant debt problems in 2011, exporting remains a success.

Primary sector

The primary sector constitutes about 5% of Irish GDP, and 8% of Irish employment. Ireland's main economic resource is its large fertile pastures, particularly the midland and southern regions. In 2012 Ireland exported approximately €9 billion worth of agri-food and drink (about 8.4% of Ireland's exports), mainly as cattle, beef, and dairy products. Ireland's agri-food exports are expected to grow and are led by a number of large Irish companies including Kerry Group, Glanbia and Greencore.

In the late nineteenth century, the island was mostly deforested. In 2005, after years of national afforestation programmes, about 9% of Ireland has become forested.[132] It is still one of the least forested countries in the EU and heavily relies on imported wood.[133] Its coastline – once abundant in fish, particularly cod – has suffered overfishing and since 1995 the fisheries industry has focused more on aquaculture. Freshwater salmon and trout stocks in Ireland's waterways have also been depleted but are being better managed.[134] Ireland is a major exporter of zinc to the EU and mining also produces significant quantities of lead and alumina.[135]

Beyond this, the country has significant deposits of gypsum, limestone, and smaller quantities of copper, silver, gold, barite, and dolomite.[136] Peat extraction has historically been important, especially from midland bogs, however more efficient fuels and environmental protection of bogs has reduced peat's importance to the economy.[137] Natural gas extraction occurs in the Kinsale Gas Field and the Corrib Gas Field in the southern and western counties,[138] where there is 19.82 bn cubic metres of proven reserves.[136]

The construction sector in Ireland has been severely affected by the Irish property bubble and the 2008-2013 Irish banking crisis and as a result contributes less to the economy than during the period 2002–2007.

While there are over 60 credit institutions incorporated in Ireland,[139] the banking system is dominated by the AIB Bank, Bank of Ireland and Ulster Bank.[140] There is a large Credit Union movement within the country which offers an alternative to the banks. The Irish Stock Exchange is in Dublin, however, due to its small size, many firms also maintain listings on either the London Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. That being said, the Irish Stock Exchange has a leading position as a listing domicile for cross-border funds. By accessing the Irish Stock Exchange, investment companies can market their shares to a wider range of investors (under MiFID although this will change somewhat with the introduction of the AIFM Directive. Service providers abound for the cross-border funds business and Ireland has been recently rated with a DAW Index score of 4 in 2012. Similarly, the insurance industry in Ireland is a leader in both retail markets and corporate customers in the EU, in large part due to the International Financial Services Centre.[141]

Welfare benefits

As of December 2007, Ireland's net unemployment benefits for long-term unemployed people across four family types (single people, lone parents, single-income couples with and without children) was the third highest of the OECD countries (jointly with Iceland) after Denmark and Switzerland.[142] Jobseeker's Allowance or Jobseeker's Benefit for a single person in Ireland is €188 per week, as of March 2011.[143] State provided old age pensions are also relatively generous in Ireland. The maximum weekly rate for the State Pension (Contributory) is €230.30 for a single pensioner aged between 66 and 80 (€436.60 for a pensioner couple in the same age range).[144] The maximum weekly rate for the State Pension (Non-Contributory) is €219 for a single pensioner aged between 66 and 80 (€363.70 for a pensioner couple in the same age range).[145]

Wealth distribution and taxation

.png)

The percentage of the population at risk of relative poverty was 21% in 2004 – one of the highest rates in the European Union.[146] Ireland's inequality of income distribution score on the Gini coefficient scale was 30.4 in 2000, slightly below the OECD average of 31.[147] Sustained increases in the value of residential property during the 1990s and up to late 2006 was a key factor in the increase in personal wealth in Ireland, with Ireland ranking second only to Japan in personal wealth in 2006.[148] However, residential property values and equities have fallen substantially since the beginning of 2007 and major declines in personal wealth expected.[149]

From 1975 to 2005, tax revenues fluctuated at around 30% of GDP (see graph right).

Currency

Before the introduction of the euro notes and coins in January 2002, Ireland used the Irish pound or punt. In January 1999 Ireland was one of eleven European Union member states which launched the European Single Currency, the euro. Euro banknotes are issued in €5, €10, €20, €50, €100, €200 and €500 denominations and share the common design used across Europe, however like other countries in the eurozone, Ireland has its own unique design on one face of euro coins.[150] The government decided on a single national design for all Irish coin denominations, which show a Celtic harp, a traditional symbol of Ireland, decorated with the year of issue and the word Éire.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Ireland". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ "National Income and Expenditure Annual Results". Cso.ie. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ "Consumer Price Index February 2015 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Survey on Income and Living Conditions 2013 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ http://www.compareyourincome.org/

- ↑ http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_di12

- ↑ "Quarterly National Household Survey Quarter 4 2014 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "CSO figures show unemployment below rate of autumn 2008". BreakingNews.ie. 31 May 2016.

- ↑ "CSO QuickTables - ss="p - Earnings and Labour Costs". Cso.ie. 26 November 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ http://www.cso.ie/multiquicktables/quickTables.aspx?id=ehq03_ehq08

- ↑ "Doing Business in Ireland 2015". World Bank. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Goods Exports and Imports December 2014 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 "International Investment Position and External Debt September 2014 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "BUDGET 2015 ECONOMIC AND FISCAL OUTLOOK (Incorporating Economic and Fiscal Statistics and Tables)" (PDF). Government of Ireland (budget.gov.ie). 2015.

- ↑ "Credit ratings national treasury management agency". NYMA. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "Country Statistical Profiles". OECD. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Standard & Poor's raises Ireland's credit rating to A+". RTÉ. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ "Fitch restores A grade to Irish economy". Treasury Management Agency. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Central Bank of Ireland. "Central Bank of Ireland - Official External Reserves". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ "Oecd Gdp". Stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Annual Competitiveness Report 2008, Volume One: Benchmarking Ireland's Performance" (PDF). NCC. 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- 1 2 "The Economist Intelligence Unit's quality-of-life index" (PDF). (67.1 KB) – The Economist

- 1 2 Charles Smith, article: 'Ireland', in Wankel, C. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Business in Today's World, California, USA, 2009.

- ↑ "Irish corporate tax 2015, tax, taxation, taxes, R&D credit, corporation, 2014, Taxation, Personal, Income, Stamp Duty, Capital Gains, Property, Rates". Finfacts Ireland. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ "Ireland GDP – real growth rate". Index Mundi. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Quarterly National Accounts -Quarter 1 2012" (PDF). CSO. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ↑ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (13 March 2008). "Irish banks may need life-support as property prices crash". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ Bowlby, Chris (13 April 2010). "Greeks and Irish look for jobs abroad". BBC News.

- ↑ "Quarterly National Accounts -Quarter 1 2013" (PDF). CSO. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ "European Economic Forecast Spring 2013". Economic forecasts. European Commission. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "How Ireland became the Celtic Tiger", Sean Dorgan, the chief executive of IDA. 23 June 2006

- ↑ O'Toole, Francis; Warrington. "Taxations And savings in Ireland" (PDF). Trinity Economic Papers Series. Trinity College, Dublin. p. 19. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ↑ De Vlieghere, Martin (25 November 2005). "The Myth of the Scandinavian Model | The Brussels Journal". The Brussels Journal<!. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "Consumer Prices Bi-annual Average Price Analysis Dublin and Outside Dublin: 1 May 2006" (PDF). (170 KB) – CSO

- ↑ Guider, Ian (7 August 2008). "Inflation falls to 4.4pc". Irish Independent. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ↑ "Consumer Price Index July 2008 (Dublin & Cork, 7 August 2008" (PDF). (142 KB) – Central Statistics Office. Retrieved on 8 August 2008.

- ↑ "Economic Survey of Ireland 2006: Keeping public finances on track". OECD. 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ↑ "House slowdown sharper than expected". RTÉ. 3 August 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ "Latest Report: Latest edition of permanent tsb / ESRI House price index – May 2007". Permanent TSB, ESRI. Archived from the original on 28 August 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- ↑ "EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC)" (PDF). (161 KB) CSO, 2004.

- ↑ "CSO – Central Statistics Office Ireland". Central Statistics Office Ireland. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (13 March 2008). "Irish banks may need life-support as property prices crash". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Ireland's credit rating downgraded". RTÉ.ie. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ↑ "Ireland's credit rating downgraded". irishtimes.ie. 24 November 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ireland's credit rating downgraded". standardandpoors.com. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ireland out of recession as exports jump". The Independent. London. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ireland out of recession but needs faster growth". BusinessDay. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Irish economy contracts by 1.2%". BBC News. 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "Shrinking Irish economy heightens debt risk". Reuters. 24 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "New Eurostat website - Eurostat – Industrial production down by 0.9% in euro area and Ireland will exit its bail out program in December 2013" (PDF). epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Andras Gergely (1 October 2008). "Irish finmin sees bank liquidity, not solvency issue". Reuters.

- 1 2 3 Collins, Liam (12 October 2008). "Top developers see asset values dive two-thirds". Irish Independent.

- ↑ "Unemployment rising at record rate". RTÉ. 1 October 2008.

- ↑ "Irish Agricultural Land Research" (PDF). Savills Hamilton Osbourne King. May 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ Morgan Kelly, Professor of Economics, University College Dublin. "Just How Sound is the Irish Banking System?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007.

- ↑ Oliver, Emmet (31 August 2008). "New waive of Irish banking". Sunday Tribune. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ↑ "Banks call in leading developers ahead of property write-downs". Sunday Tribune. 12 October 2008.

- ↑ "AIB Half-Yearly Financial Report 2008". Allied Irish Banks. 30 July 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ "Reports and Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2008". Bank of Ireland. 10 June 2008. p. 73. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ↑ "Government Decision to Safeguard Irish Banking System". Government of Ireland, Department of the Taoiseach. 30 September 2008.

- ↑ "Seven Deadly Sins... (of omission)". Sunday Tribune. 5 October 2008.

- ↑ "Anglo Irish directors step down, bank downgraded". Irishtimes.com. 19 January 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ "Bank shares lose half their value in market 'carnage'". Irishtimes.com. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ Charlie Weston (11 October 2008). "State mortgage plan for first-time buyers". Irish Independent. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ↑ Simon Carswell, Fiona Reddan (7 October 2008). "Another traumatic day for investors in Irish banks". Irish Times. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ↑ "NIB figures hint at depth of bad debt problems". Sunday Tribune. 12 October 2008.

- ↑ "Extra year for Ireland under €85 billion plan". RTÉ.ie. 28 November 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ "Govt four-year plan unveiled - As it happened - RTÉ News". rte.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Budget adjustment for 2011 to total €6bn - RTÉ News". rte.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Government Finance Statistics October 2014 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Live Register December 2014 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". cso.ie. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Kenny, Gilmore and Bruton on hand for job actions plan launch". Ireland News. Net. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Sweeney, Tanya (19 December 2014). "Soapbox... Is the boom really back? ...and Is the so-called 'Celtic Phoenix' all it's cracked up to be?". Irish Independent. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "Rise of the Celtic Phoenix?". Shelflife Magazine. 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ireland is a spending nation once again as Celtic Phoenix rises". Irish Independent. 24 August 2014.

- ↑ "GDP growth of 4.8% makes Ireland fastest growing EU economy". RTÉ News. 12 March 2015.

- ↑ "Irish economic growth outpacing rest of Europe, says Ibec". The Irish Times. 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Rise of new orders for 'battered' Irish construction sector indicates recovery". Irish Independent. 10 March 2014.

- ↑ "Strong growth sees national debt fall to 109% of GDP". Irish Times. 20 April 2015.

- ↑ "Unemployment steady at 10% in April - CSO". RTÉ News. 29 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ireland tops the European poll for reducing unemployment rates". The Irish Times. 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "Population and Migration Estimates". Central Statistics Office. 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Emigration of Irish nationals falls 20% in year to April". The Irish Times. 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Property prices nationally up 15 per cent in 12 months". The Irish Times. 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Dublin property price growth fell below national average in first three months of 2015". RTÉ News. 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Kelly, Olivia (25 May 2015). "Dublin city social housing list tops 20,000". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "37,000 mortgages in arrears of over 720 days". 27 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ "Budget Key Points". RTÉ News. 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Budget 2015: Give and take". Irish Independent. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Budget 2015: as it happened". RTÉ News. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Noonan denies budget framed for election". Irish Examiner. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Budget 2015". Irish Times. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Expansionary budgets until 2020 are possible - Spring Economic Statement". RTÉ News. 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Spring statement: the main points". The Irish Times. 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Spring Economic Statement Speech by the Minister for Finance". Department of Finance. 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble: 'Germany jealous of Irish growth figures'". Irish Independent. 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Enda Kenny says Irish economy strengthening but remains fragile". The Irish Times. 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "No going back to boom and bust, says Kenny". The Irish Times. 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "Enda Kenny: 2015 is the year of rural recovery". Irish Examiner. 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Budget 2016: European Commission warns any extra revenues be used to cut debt". Irish Independent. 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Myth of the Irish Recovery". CounterPunch. 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "Celtic phoenix - Ireland's economy emerges from ashes". Australian Financial Review. 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "IMF sounds warning note over economic recovery". The Irish Times. 2 May 2015.

- ↑ "Tánaiste Joan Burton warns Ireland's economic recovery is not secure". The Irish Times. 29 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Phoney Celtic Phoenix". Broadsheet.ie. 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "What does 'Brexit nightmare' mean for Ireland?". The Irish Times. 24 June 2016.

- ↑ "Britain votes to leave EU: What does it mean for Ireland?". RTÉ.ie. 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "Brexit: Move could see flood of funds shift to Dublin - FT". The Irish Times. 16 June 2016.

- ↑ "The real story behind Ireland's 'Leprechaun' economics fiasco". RTÉ. 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 "'Leprechaun economics' - Ireland's 26pc growth spurt laughed off as 'farcical'". Irish Independent. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Meat company's relocation to Ireland unlikely to affect GDP". Irish Times. 10 August 2016.

- ↑ "Irish GDP growth at staggering 26.3pc last year, economist says figures are 'meaningless'". Irish Independent. 12 July 2016.

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesABFI/Home!OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesBeer/Industry_in_Ireland~beer-industry-in-ireland!OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesCider/Industry_in_Ireland~cider-industry-in-ireland!OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesSpirits/Industry_in_Ireland~spirits-industry-in-ireland!OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesWhiskey/Industry_in_Ireland~Whiskey_industry_in_Ireland~economic-impact!OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.abfi.ie/Sectors/ABFI/ABFI.nsf/vPagesWine/Industry_in_Ireland~wine-industry-in-ireland!OpenDocument

- 1 2 http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/financial-services/

- ↑ http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/engineering/

- ↑ http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/ict/

- ↑ http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/software/

- ↑ http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/medical-technology/

- ↑ http://www.idaireland.com/business-in-ireland/industry-sectors/bio-pharmaceuticals/

- ↑ "Operational Irish Mines: Tara, Galmoy and Lisheen « Irish Natural Resources". Irish Natural Resources. 15 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "Ireland top location for US Multinational Profits". Finfacts.ie. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Kevin (26 March 2005). "Ireland: How the Celtic Tiger Became the World's Software Export Champ". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- 1 2 Howley, Martin, Fergal O'Leary, and Brian Ó Gallachóir (January 2006). Energy in Ireland 1990 – 2004: Trends, issues, forecasts and indicators (pdf), p10, 20, 26.

- ↑ "Bord Gáis Homepage". Bord Gáis. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "Winning in a polycentric world: globalization and the changing world of business - The Globalization Index 2010 summary - EY - Global". ey.com. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ World Resources Institute (2006). Forests, Grasslands and Drylands: Ireland. EarthTrends. Retrieved on 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Heritage Council of Ireland. 1. Historical Context & 2. Ireland's Forestry Policy. Forestry and the National Heritage. Retrieved on 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Indecon International Economic Consultants, for the Central Fisheries Board (April 2003)An Economic/Socio-Economic Evaluation of Wild Salmon in Ireland at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2009)

- ↑ Newman, Harold R. The Mineral Industry of Ireland (pdf). U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook – 2001.

- 1 2 CIA (2006). Ireland The World Factbook. Retrieved on 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Feehan, J, S. McIlveen (1997). The Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape. Cork University Press.

- ↑ Bord Gáis (2006). 97&3nID=354&nID=364 Natural Gas In Ireland. Gas and the Environment. Retrieved on 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Department of Finance. Banking in Ireland Report of the Department of Finance: Central Bank Working Group on Strategic Issues facing the Irish Banking Sector. Retrieved on 7 August 2006.

- ↑ Adkins, Bernardine and Simon Taylor, (June 2005). Banks in Northern Ireland face Competition Commission investigation (pdf). Report & Review.

- ↑ International Monetary Fund, (20 February 2001). Insurance Supervision Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC): Ireland.] Retrieved on 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Finfacts Ireland. . Retrieved on 10 August 2008.

- ↑ Citizens Information. . Retrieved on 4 March 2011.

- ↑ Citizens Information. . Retrieved on 4 March 2011.

- ↑ Citizens Information. . Retrieved on 4 March 2011.

- ↑ Central Statistics Office, Ireland (June 2006). Measuring Ireland's Progress: 2005 (pdf). ISBN 0-7557-7142-7.

- ↑ OECD. Country statistical profiles 2006: Ireland. OECD Statistics. Retrieved on 7 August 2006.

- ↑ Finfacts Ireland. . Retrieved on 10 August 2008.

- ↑ Sunday Tribune. . Retrieved on 10 August 2008.

- ↑ "Design for Irish coin denominations". Myguideireland.com. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

External links

- Ireland:A Test Case of PIGS Austerity

- Map of Ireland's oil and gas infrastructure

- Tariffs applied by the Republic of Ireland as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements