English heraldry

.svg.png) Armorial bearings of King Richard I of England, often referred to as the "arms of England". | |

| Heraldic tradition | Gallo-British |

|---|---|

| Governing body | College of Arms |

| Chief officer | Thomas Woodcock (officer of arms), Garter Principal King of Arms |

English heraldry is the form of coats of arms and other heraldic bearings and insignia used in England. It lies within the so-called Gallo-British tradition. Coats of arms in England are regulated and granted to individuals by the English kings of arms of the College of Arms. They are subject to a system of cadency to distinguish between sons of the original holder of the coat of arms. The English heraldic style is exemplified in the arms of British royalty, and is reflected in the civic arms of cities and towns, as well as the noble arms of individuals in England. Royal orders in England, such as the Order of the Garter, also maintain notable heraldic bearings.

Characteristics

Like many countries' heraldry, there is a classical influence within English heraldry, such as designs originally on Greek and Roman pottery. Many coats of arms feature charges related to the bearer's name or profession (e.g. Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, depicting bows quartered with a lion), a practice known as "canting arms". Some canting arms make references to foreign languages, particularly French, such as the otter (loutre in French) in the arms of the Luttrel family.[1]

Representations in person of Saints or other figure are very rare, although there are however a few uses, mostly originating from seals, where there have never been such limitations.[2] Although many places have dropped such iconography, the Metropolitan Borough of St Marylebone, London, includes a rendering of the Virgin Mary, although this is never stated.[3] This is also the case in many other examples, particularly those depicting Christ, to remove religious complications. Unlike in mainland Europe where family crests make a large use of their eponymous Saints, these are few and far between in England.

The lion is the most common charge, particularly in Royal heraldry.[4] Heraldic roses are also common in English heraldry, as in the War of the Roses where both houses, Lancaster and York, used them, and in the ensuing Tudor dynasty. The heraldic eagle, while common on the European continent and particularly in Germany, is relatively rare in English heraldry and, in early English heraldry, was often associated with alliances with German princes.[5]

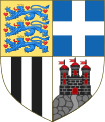

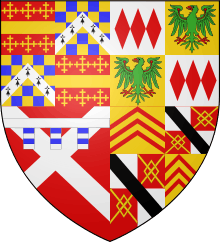

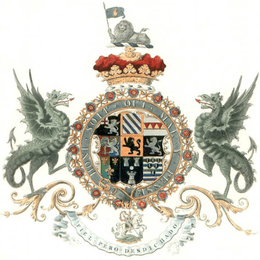

The coat of arms of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, pictured on the left, uses almost all typical forms of heraldry in England: The first quarter consists of his father-in-law, Richard Beauchamp, who bore with an escutcheon of De Clare quartering Despenser, now shown in Neville's fourth quarter. The second quarter shows the arms of the Montacutes (Montagu). The third quarter shows the arms of Neville differenced by a label for Lancaster.[6]

History

The first use of heraldry associated with the English was in the Bayeux Tapestry, recounting the events of the Battle of Hastings in 1066, where both sides used emblems in similar ways.

The first Royal Coat of Arms was created in 1154 under Henry II, the idea of heraldry becoming popular among the knights on the first and second crusades, along with the idea of chivalry.[8] Under Henry III it gained a system of classification and a technical language, confirming its place as a science.[9] However, over the next two centuries the system was abused, leading to the swamping of true coats-of-arms.[9]

For the rest of the medieval period it was popular within the upper classes to have a distinctive family mark for competitions and tournaments, and was popular (although not prevalent) within the lower classes. It found particular use with knights, for practice and in the mêlée of battle, where heraldry was worn on embroidered fabric covering their armour. Indeed, their houses' signs became known as coats-of-arms in this way.[10] They were also worn on shields, where they were known as shields-of-arms.[10] As well as military uses, the main charge was used in the seals of households. These were used to prove the authenticity of documents carried by heralds (messengers) and is the basis of the word heraldry in English.[11] One example of this is the seal of John Mundegumri (1175), which bears a single fleur-de-lys.[12] Prior to the 16th century, there was no regulation on the use of arms in England.[13]

Rolls of Arms

One of the first contemporary records of medieval heraldry is a roll of arms called Falkirk Rolls written soon after the Battle of Falkirk in 1298. It includes the whole range of recognised heraldic colours (including furs) and designs.[14] This clearly demonstrates that English heraldry was fully developed at this time, and although the language is not quite identical, much of the terminology is the same as is still used. It is an occasional roll of arms, meaning it charted the heraldry visible on one occasion. Other rolls of arms covering England include the Caerlaverock Poem (composed 1300 about siege of Caerlaverock) and Glover's Roll (a mixed and varied collection from around the mid-13th century).

Court of the Earl Marshal

The position of herald in England was well defined, and so on January 5, 1420, William Bruges was appointed by King Henry V to be Garter King of Arms. No such position had been created in other countries.[15] A succession of different titles was introduced over the next four centuries for principal governor of arms, including King of Arms. Some were members of the College of Arms, some were not. Other holders of positions included the Falcon King of Arms, a position created under King Edward III. Other positions were created for important counties, such as the Lancastrian King of Arms, but the balance of power between them and those charged with larger regions remains unclear.[16]

During the Tudor period, grants of arms were made for significant contributions to the country by one of the Herald and Kings of Arms in a standard format, as in the case of Thomas Bertie, granted arms on 10 July 1550.[17] This was given as a passage read out by the herald. Although many are written in English,[17] it is possible they were also read out in Latin.[18]

The introduction in his case read:

To all noble and gentled the present letters reading hearing or seeing, Thomas Hawley alias Clarencieulx principal Herald and King of Arms of the south-east and west parts of this realm from the river Trent southward, sendeth humble commendation and greeting.

This seems to be the standard introduction, each herald using their name and position.

Nadir of English Heraldry

The early 18th century is often considered the nadir of English heraldry.[19][20][21] The heraldic establishment was not held in high regard by the public; the authority of the Court of Chivalry (though not its armorial jurisdiction) was challenged,[22] and an increasing number of 'new men' simply assumed arms, without any authority.[19] This attitude is evident even in the appointment of the heralds themselves—Sir John Vanbrugh, a prominent dramatist and architect who knew nothing of heraldry, was appointed to the office of Clarenceux King of Arms, the second-highest office in the College of Arms.[23] No new grants were made between November 1704 and June 1707.[24]

The situation slowly improved throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with the number of new grants per year slowly rising—14 in 1747,[21] 40 in 1784 and 82 in 1884.[25] These numbers reflect an increasing geographical spread in grantees, due to a general increase of interest in heraldry. This was caused by a number of factors, including the creation of the Order of the Bath in 1725, and grants of arms to its members, augmentations for honour granted to successful military commanders in the Peninsular and Napoleonic wars, and the rise in popularity of name and arms clauses.[26] The medieval period, and with it heraldry, also became popular as a result of the Romantic movement and Gothic revival.[27]

Timeline

12th century

- 1127: King Henry I presents Count Geoffrey of Anjou with arms, the earliest recorded royal bestowal of arms in the kingdom.[28]

- 1198: King Richard the Lionheart introduces royal arms, depicting three lions; they remain the arms of England to this day.[29]

13th century

- Early examples of arms in Wales: Prince David ap Llewellyn 1246 and John ap John of Grosmont in 1249.

- 1256: Walter le Vyelur, a painter, is an early example of a tradesman bearing arms.[30]

- c1276: The earliest reference to a Norroy King of Arms.

- 1290s: The earliest known diocesan arms, for the See of Ely.[31]

14th century

- 1334: The earliest reference to a Clarenceux King of Arms.

- After claiming the French throne in 1340, King Edward III quarters the French and English royal arms. The French arms remain part of the English arms for 460 years.

- From 1340, the customary method of differencing the royal arms is a label (plain for the prince of Wales, bearing charges for other royals).

- 1345: The Court of Chivalry hears its first heraldry case.

- c1380: London assumes civic arms.

- 1385–90: The famous case of Scrope v Grosvenor in the Court of Chivalry.

- 1390s: Johannes de Bado Aureo publishes Tractatus de Armis.

15th century

- By 1410, "a non-armigerous gentlemen is a rarity needing explanation."[32]

- 1411: Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, is an early example of bishops impaling their personal arms with those of their sees.

- 1415: King Henry V establishes the office of Garter King of Arms, and makes him senior to the other kings of arms. William Bruges is the first Garter 1415–50.

- 1418: Henry V temporarily prohibits the bearing of self-assumed arms during his campaign in France; for some reason, this was later interpreted as a ban on self-assumed arms throughout England.

- The three kings of arms are authorised to grant coats of arms,[32] but self-assumption remains the norm.

- By 1423, St Bartholomew's Hospital in London has assumed arms – probably the oldest example of medical heraldry in the kingdom.

- 1439: Garter Bruges grants arms to the Worshipful Company of Drapers – the earliest known grant by a king of arms.[29]

- King Henry VI grants arms to King's College (Cambridge) in 1441 and Eton College in 1449 – the earliest examples of academic heraldry in England.

- 1484: King Richard III organises the royal kings of arms, heralds, and pursuivants into a College of Arms, under authority of the Earl Marshal.

- 1485: King Henry VII revokes the College of Arms' charter.

- c1500: Garter John Wrythe introduces a system of distinguishing younger sons by adding marks of cadency to their paternal arms.[29]

16th century

- In Wales, the bards attribute arms wholesale to the ancestors of the tribes. These are then "inherited" by their descendants.

- 1530: King Henry VIII introduces heraldic visitations to record arms in use and prohibit any that are usurped or are borne by men of inferior social status.

- 1538: Gloucester obtains a grant of arms, the first civic arms to be granted in England.

- 1555: Queen Mary I of England reincorporates the College of Arms with a new charter.

- 1561: The College of Arms rules that heraldic heiresses may not transmit their fathers' crests to their descendants.[29]

- 1562: Gerard Leigh publishes The Accedence of Armory.

- 1573: The University of Cambridge is granted arms.[33]

- 1574: Arms of the University of Oxford and its colleges are recorded in a visitation.[33]

17th century

- 1603: King James VI of Scotland inherits the English throne in 1603. The English and Scottish royal arms are combined, and a quartering depicting a harp is devised for Ireland.

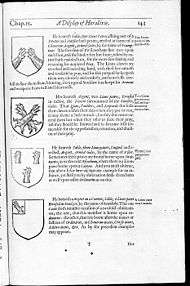

- 1610: John Guillim publishes A Display of Heraldry.

- 1646: During its civil war again King Charles I, Parliament closes the Court of Chivalry and appoints its own kings of arms in place of those who have remained loyal to the king.

- 1649–60: While England is a republic ('Commonwealth'), the royal arms are replaced by new state arms.

- 1660: The monarchy is restored and King Charles II nullifies grants made by the Commonwealth heralds.

- 1667: The Court of Chivalry reopens.

- Garter Sir William Dugdale states that assumed arms that have been used in a family for around 80 years are allowed to be borne by prescription.[34]

- 1672: Charles II makes the office of Earl Marshal hereditary to the Dukes of Norfolk.

- 1673: The College of Arms opens a register of arms.[29]

- From 1673, the kings of arms require the Earl Marshal's authority for each grant of arms.[29]

- 1681–87: The last round of visitations is held. The system lapses after the 'Glorious Revolution' 1688–89.

18th century

- Garter Henry St George begins to undermine the principle of bearing self-assumed arms by prescription by refusing to confirm them without formally granting them.[34]

- 1707: England and Scotland unite to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, but retain their separate heraldry laws and authorities.

- 1737: The Court of Chivalry ceases to function.

- From 1741, gentlemen have to be "eminent" to be eligible for grants of arms.[29]

- 1780: Joseph Edmondson publishes A Complete Body of Heraldry.

- 1798: Annual licensing of coats of arms is introduced to raise money for the war with France. It is discontinued after the war.

19th century

- 1801: Great Britain and Ireland amalgamate to form the United Kingdom, but the English, Scottish and Irish heraldry authorities remain separate. The royal arms are altered to reflect the union, and the French arms are dropped.

- From 1806, an officer of the College of Arms is Inspector of Regimental Colours, to oversee British army heraldry.[35]

- 1815: The College of Arms confirms that only peers and knights of the Garter and the Bath are entitled to supporters to their arms.[29]

- 1823–1944: Annual licensing of coats of arms (whether they are officially recognised or not) is reintroduced.

- 1842: Bernard Burke publishes The General Armory.

- 1859: James Fairbairn publishes A Book of Crests.

- 1863: Charles Boutell publishes The Manual of Heraldry.

- 1889: West Sussex County Council obtains a grant of arms, the first to a county council.[31]

- 1889: Charles Elvin publishes A Dictionary of Heraldry.

- 1892: James Parker publishes A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry.

- 1894: Arthur Fox-Davies publishes The Book of Public Arms.

- 1895: Arthur Fox-Davies publishes Armorial Families.

- 1894: Mr Lloyd of Stockton registers personal arms containing 323 quarterings.[29]

20th century

- 1902: Joseph Foster publishes Some Feudal Coats of Arms.

- 1906: The Earl Marshal authorises the granting of badges to armigers of all ranks.[29]

- 1909: Arthur Fox-Davies publishes A Complete Guide to Heraldry.

- 1919: The Royal Navy introduces a standard system of ships' badges. HMS Warwick is the first to bear an official badge.

- 1924: The Royal Air Force College Cranwell obtains a grant of arms, the first to the RAF.[31][35]

- 1927: Bocking is the first parish council to obtain a grant of arms.[31]

- 1935: A standard pattern for Royal Air Force unit badges is introduced.[35]

- 1939: Anthony Wagner (Portcullis Pursuivant) publishes Historic Heraldry of Britain.

- 1943: King George VI transfers the office of Ulster King of Arms to the College of Arms and combines it with the office of Norroy, with jurisdiction limited to Northern Ireland.

- 1946: Anthony Wagner publishes Heraldry in England.

- 1947: The Society of Heraldic Antiquaries (later the Heraldry Society) is established. It launches a journal, The Coat of Arms, in 1950.

- 1950: The College of Arms introduces a mark of difference for the arms of divorced women.

- 1951: The first grants of arms to Northern Ireland: Londonderry and Tyrone.

- 1954: The Court of Chivalry is reactivated for a test case between the Manchester City Council and a local theatre.[35]

- 1960: The Earl Marshal authorises the kings of arms to devise arms, on request, for towns in the United States of America, subject to approval by the relevant state governors. This is extended to other corporate bodies in the USA in 1962.[35]

- 1967: The Earl Marshal authorises ecclesiastical hats for the arms of Roman Catholic clergy.

- 1971: Geoffrey Briggs' Civic & Corporate Heraldry

- 1973: John Brooke-Little (Richmond Herald)'s An Heraldic Alphabet

- 1976: The Earl Marshal authorises ecclesiastical hats for the arms of Anglican clergy.

- 1988: Thomas Woodcock (Somerset Herald) and John Robinson (Fitzalan Pursuivant) publish The Oxford Guide to Heraldry.

- 1993: Peter Gwynn-Jones (York Herald) and Henry Paston-Bedingfeld (Rouge Croix Pursuivant) publish Heraldry.

- 1995 and 1997: The College of Arms revises the rules for women's arms; inter alia, married women may now bear their arms on shields, with a mark of difference.[36]

Regulation

Heraldry in England is heavily regulated by the College of Arms, who issue the arms. A person can be issued the arms themselves, but the College fields many requests from people attempting to demonstrate descent from an armigerous (arms-bearing) person;[37] a person descended in the male line (or through heraldic heiresses) from such an ancestor may be reissued that ancestor's arms (with differencing marks if necessary to distinguish from senior-line cousins). To that end, the college is involved in genealogy and the many pedigrees (family trees) in their records, although not open to the public, have official status. Anyone may register a pedigree with the college, where they are carefully internally audited and require official proofs before being altered.

Applications are open to anyone with a 'reputable status' (normally including a university degree, but officially down to the discretion of the College).

The College of Arms was incorporated in 1484 by King Richard III,[38] and is a corporate body consisting of the professional heralds who are delegated heraldic authority by the British monarch. Based in London, the College is one of the few remaining government heraldic authorities in Europe. Its legal basis relies on the Law of Arms, which makes the right to grant arms exclusively to due authority, which has, since the late medieval period, been the Monarch or State, who gives the College of Arms this right and duty. Much of it is under the personal responsibility of the Monarch and not government, although the College has always been self-funded and independent.

According to one source,[39] the number of grants of arms in each half-century was roughly as follows:

| 1550–1600 | 1600–1650 | 1650–1700 | 1700–1750 | 1750–1800 | 1800–1850 | 1850–1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2600 | 1580 | 780 | 560 | 1600 | 4600 | 3800 |

Although the accuracy of the figures is in doubt, the general trend is likely to be correct.[39] It is clear that heraldry saw a resurgence in England in the early 19th century.

Since 1797, no case of free assumption of arms has ever been successfully prosecuted in England.[13] The Court of Chivalry, the court of enforcement of such cases, has fallen into unimportance.[13]

Cadency

The English system of cadency involves the addition of a brisure, or mark of difference to the coat of arms, to identify the bearer's rank in the order of inheritance from the bearer of the original coat. Although there is some debate over how strictly the system should be followed, the accepted system is shown below:

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | Seventh | Eighth | Ninth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Son | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

†also known as an octofoil[40]

Daughters have no special brisures, and customarily bear their father's arms on a lozenge while they are unmarried.[41] While she is married, a woman may marshal (combine) her father's arms with her husband's on a single shield, normally by impalement,[42] but upon becoming a widow, she returns to bearing her father's arms upon a lozenge, though now impaled with her late husband's arms.[41] Her husband's arms are borne on the dexter side and her father's arms on the sinister side.

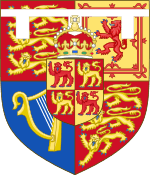

Royal coat of arms

The Royal coat of arms is the official coat of arms of the British monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II.[43] These arms are used by the Queen in her official capacity as monarch, and are officially known as her Arms of Dominion. Variants of the Royal Arms are used by other members of the Royal Family; and by the British Government in connection with the administration and government of the country.[43] In Scotland, the Queen has a separate version of the Royal Arms, a variant of which is used by the Scotland Office.[43]

The shield is quartered, depicting in the first and fourth quarters the three lions passant guardant of England; in the second, the rampant lion and double tressure flory-counter-flory of Scotland; and in the third, a harp for Ireland.[44]

The crest is a lion statant guardant wearing the imperial crown, itself standing upon another representation of that crown.

The dexter supporter is a likewise crowned lion, symbolizing England; the sinister, a unicorn, symbolising Scotland.[43] According to legend, a free unicorn was considered a very dangerous beast; therefore the heraldic unicorn is chained, as were both supporting unicorns in the Royal coat of arms of Scotland.

The coat features both the motto of English monarchs, Dieu et mon droit (God and my right), and the motto of the Order of the Garter, Honi soit qui mal y pense (Shamed be he who thinks ill of it) on a representation of the Garter behind the shield.[43]

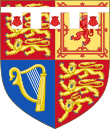

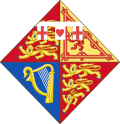

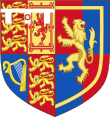

Coat of arms of the British Royal Family

Direct descendants of a monarch have royal coats of arms. Although many are given peerage titles named for places in Wales or Scotland, the Royal Family follows an English heraldic tradition; indeed, most coats of arms of the royal family are based on the Royal Coat of Arms, as above.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

County families

The Heraldic Visitations of the several counties of England were instituted in the 16th century and required each family which displayed coat armour to report to the visiting heralds, generally holding court in the county capital during a certain period, to declare its pedigree to show it came from ancient gentry stock. This has given rise to well recorded armorials of the ancient gentry families from each county, which generally assumed amongst themselves the administration of the county on behalf of the monarch, filling such offices as Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Commissioners, Knights of the Shire or Members of Parliament, and in the feudal era if tenants-in-chief fought in the royal army.

Civic armory

Almost every town council, city council and major educational establishment has an official armorial bearing (coat of arms), although the use of such arms varies wildly, due to the governance of the institution, and who uses the arms, particularly concerning unitary authorities. The College of Arms grants arms only to people or corporate bodies, and so coats of arms are attributed to Borough, District or Town councils, rather than to a place or its populace.[46] Mottos are common but not universal. Arms of such councils may feature the historical ecclesiastical arms of a local church, cathedral or diocese, such as the arms of Watford Borough Council which feature the arms of the Diocese of St. Albans. Similarly they can also feature the arms of a local patron Saint, as in the arms of St. Edmundsbury Borough Council which features the coat of arms of Saint Edmund.[47] Another example is the use of the rose, the symbol of the Virgin Mary.[48] Others are derived from the arms of an associated influential family or local organisation, or their creation is granted as an honour to an influential person.

In local government, however, there has been a move away from traditional heraldic style designs to clean, streamlined ones, as in the case of London. Whether this is a good or bad thing is a matter of debate.

Often use is restricted to certain events and institutions within the town or city, its use superseded by the logo of the local borough council or Arms Length Management Organisation. Current uses of historical coats of arms normally include use in town halls and on litter bins and benches (where corporate-style council logos are deemed inappropriate).[48]

Educational Institutions

Many British educational establishments have arms dating back hundreds of years, but the College of Arms continues to grant new arms to schools, colleges and universities each year. The arms of educational establishments often represent the aims of the institution and history of the establishment, town or major alumni.

For instance the Letters Patent granting Arms to the University of Plymouth were presented by Eric Dancer, CBE, JP, Lord Lieutenant of Devon, in a ceremony at the University on 27 November 2008, in the presence of Henry Paston-Bedingfeld, York Herald of the College of Arms, the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress of Plymouth, Judge William Taylor, the Recorder of Plymouth, and Baroness Wilcox.[49] The books represent the University's focus on learning and scholarship. The scattering of small stars represents navigation, which has played a key role in the history of the city and the university. The scallop shells in gold represent pilgrimage, a sign of the importance of the departure of the Pilgrim Fathers from the Barbican aboard the Mayflower in 1620. A Pelican and a Golden Hind support the shield and reflect both the original and later, better known, name of Sir Francis Drake's ship. The crest contains the Latin motto Indagate Fingite Invenite ('Explore Dream Discover'), a quote from Mark Twain, reflecting the university's ambitions for its students and Plymouth's history of great seafarers.

In the arms of Cranfield University (prepared by Sir Colin Cole, the sometime Garter Principal King of Arms), the "bars wavy" in the chief of the shield are intended in combination with the cranes to allude to the name Cranfield. The three-branched torch in the base refers to learning and knowledge in the sciences of engineering, technology and management. In the crest, the astral crown alludes to the College of Aeronautics and also commemorates the contribution of its founding Chancellor, Lord Kings Norton, to the development of aeronautical research. The keys signify the gaining of knowledge by study and instruction. The owl, with its wings expanded, may also be taken to represent knowledge in the widest sense. In the badge, which repeats the keys, the crown rayonny refers both to the royal charter under which Cranfield came into being and, by the finials composed of the rays of the sun, to energy and its application through engineering and technological skills to industry, commerce and public life. The chain which surrounds the badge shows the links between the various disciplines to be studied at the University and in itself also refers to engineering where it plays so many parts.

Heraldists

English heraldists include:

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, author of The Art of Heraldry,The Complete Guide to Heraldry and the controversial The Right to Bear (published under the pseudonym "X").

- Charles Boutell, heraldic author and writer about antiques[50]

- Constance Egan, an English heraldist, as managing editor of the Heraldry Society's journal The Coat of Arms.

- John Brooke-Little, son of the above and writer.

- Leslie Pine, an author, lecturer, and researcher in the areas of genealogy, nobility, history, heraldry and animal welfare born in Bristol.

- Cecil Humphery-Smith, OBE, FSA, a British genealogist and heraldist who founded the Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies in Canterbury.

- Guy Stair Sainty, English antiquary, art dealer, expert on chivalric orders and heraldry; author of World Orders of Knighthood and Merit, and other books.

Order of the Garter

Members of the Order of the Garter may encircle their arms with the Garter and, if they wish, with a depiction of the collar as well.[51] However, the Garter is normally used alone, and the more elaborate version is seldom seen. Stranger Knights and Ladies do not embellish the arms they use in their countries with English decorations.

Knights and Ladies Companion are also entitled to receive heraldic supporters, a privilege granted to few other private individuals. While some families claim supporters by ancient use, and others have been granted them as a special reward, only peers, Knights and Ladies Companion of the Garter, Knights and Ladies of the Thistle, and certain other knights and ladies are automatically entitled to them.[51]

On January 5, 1420, William Bruges was appointed by King Henry V to be Garter King of Arms. Since the creation of the position, it has been changed into the position Garter Principal King of Arms, but the duties remain the same. Ex officio, it also makes the position's holder head of the College of Arms, and subsequently is usually appointed from among the other officers of arms at the College. The Garter Principal is also the principal adviser to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom (particularly England, Wales and Northern Ireland) with respect to ceremonial and heraldry.[52]

See also

Heraldry of English county families:

Notes

- ↑ Boutell (1914), p. 76.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 158.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 161.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 174.

- ↑ Boutell (1914), p.92.

- ↑ Turnbull (1985), The Book of the Medieval Knight.

- ↑ Boutell (1914),p. 6.

- ↑ James Ross Sweeney (1983). "Chivalry", in The Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Volume III.

- 1 2 Boutell (1914), p. 9.

- 1 2 Boutell (1914), p. 2.

- ↑ "English etymology of Heraldry". myEtymology. Jim Sinclair. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ Illustrated in Boutell (1914), pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 3 François R. Velde. "Regulation of Heraldry in England". Heraldica. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ The Falkirk Rolls, sourced at Studies in Heraldry by Brian Timms based on Gerard J Brault, Eight Thirteenth Century Rolls of Arms, Pennsylvania State University Press (1973). Original held at the British Museum, MS Harl 6589, f9-9b. Accessed 2009-01-04.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 28.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 28–34.

- 1 2 Williams (1967), p. 261.

- ↑ Noble (1804), Appendix, p. viii.

- 1 2 Bedingfeld (1993), Heraldry, p. 67.

- ↑ Wagner (1967), p. 318.

- 1 2 Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 43.

- ↑ Wagner (1967), pp. 315–6.

- ↑ Wagner (1967), pp. 329–30.

- ↑ Wagner (1967), p. 342.

- ↑ Bedingfeld (1993), pp. 68–71.

- ↑ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Wagner (1946), p. 23.

- ↑ Wagner, A. (1946). Heraldry in England

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Woodcock, T. & Robinson, J.M. (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry

- ↑ Velde, F. (1999) [Commoners' Arms in England | http://www.heraldica.com]

- 1 2 3 4 Briggs, C. (1970). Civic and Corporate Heraldry

- 1 2 Wagner, A. (1939). Historic Heraldry of Britain

- 1 2 Fox-Davies, A.C. (1915). The Book of Public Arms

- 1 2 Pine, L.G. (1952). The Story of Heraldry

- 1 2 3 4 5 Friar, S. (Ed) (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry

- ↑ [Cheshire Heraldry | http://www.cheshire-heraldry.org.uk]

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". College of arms website. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "The history of the Royal heralds and the College of Arms". College of arms website. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- 1 2 François Velde. "Number of Grants by the English Kings of Arms". Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ "Heraldry Examination". Royal Heraldry Society of Canada. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- 1 2 Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 533–4.

- ↑ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 531.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "British Monarchy Symbols: Coat of Arms". Official British Monarchy Website. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Boutell & Brooke-Little (1978), pp. 205–222.

- ↑ "Camilla's coat of arms unveiled". BBC News. 2005-07-17.

- ↑ "Civ heraldry (homepage)". Civic heraldry of England and Wales. Robert Young. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ Compare Coat of arms of St. Edmundsbury Borough Council on Civil Heraldry by Robert Young and the coat of arms of Saint Edmund (both accessed 2009-01-06).

- 1 2 One such example, Carlisle on the City Council website. Accessed 2009-01-05.

- ↑ http://www.plymouth.ac.uk/pages/view.asp?page=24787

- ↑ Lee, Colin (2004). "Charles Boutell:Oxford Biography Index Entry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- 1 2 Paul Courtenay. "The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill". The Churchill Centre. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ "The origin and history of the various heraldic offices". College of Arms. 2004-04-10. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

References

- Bedingfeld, Henry; Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1993). Heraldry. Leicester: Magna Books. ISBN 1-85422-433-6.

- Boutell, Charles; Brooke-Little, J.P. (1983) [1950]. Boutell's Heraldry (Revised ed.). London & NY: Frederick Warne, Ltd. ISBN 0-7232-3093-5.

- Boutell, Charles (1914). Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles, ed. The Handbook to English Heraldry. London: Reeves & Turner. LCCN 25023105.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles; Johnston, Graham (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. New York: Dodge Pub. Co. ISBN 0-517-26643-1.

- Noble, Mark (1804). A History of the College of Arms. London: J. Debrett and T. Egerton. LCCN 10002228. OCLC 12772481.

- Turnbull, Stephen R. (1985). The Book of the Medieval Knight. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 0-85368-715-3.

- Wagner, Anthony R. (1967). Heralds of England: a History of the Office and College of Arms. London: HMSO. LCCN 67025497. OCLC 1178344.

- Wagner, Anthony R. (1946). Heraldry in England. London: Penguin Books. OCLC 20557263.

- Williams, C.H., ed. (1967). English Historical Documents. 5 (1485–1558). London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, Ltd. ISBN 0-413-23320-0.

- Woodcock, Thomas; Robinson, John Martin (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0-19-211658-4. LCCN 88023554.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coats of arms of England. |