Garhwali language

| Garhwali | |

|---|---|

| गढ़वळी | |

| Region | Garhwal (Uttarakhand, India) |

Native speakers |

2.9 million (2000)[1] Census results conflate some speakers with Hindi.[2] |

| Devanagari script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

gbm |

| Glottolog |

garh1243[3] |

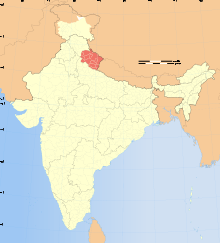

Garhwali language (गढ़वळी भाख) is a Central Pahari language belonging to the Northern Zone of Indo-Aryan languages. It is primarily spoken by the Garhwali people (गढ़वळि मन्खि) who are from the north-western Garhwal Division (गढ़वाळ) of the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand in the Indian Himalayas.

The Central Pahari languages include Garhwali and Kumauni (spoken in the Kumaun region of Uttarakhand). Garhwali, like Kumauni, has many regional dialects spoken in different places in Uttarakhand. The script used for Garhwali is Devanagari.[4]

Garhwali is one of the 325 recognised languages of India[5] spoken by over 2,267,314[6] people in Tehri Garhwal, Pauri Garhwal, Uttarkashi, Chamoli and Rudraprayag districts of Garhwal division in the state Uttarakhand.[7] Garhwali is also spoken by people in other parts of India including Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. According to various estimates, there are at least 2.5 million Garhwali migrants living in Delhi and the National Capital Region.

However, due to a number of reasons, Garhwali is one of the languages which is shrinking very rapidly. UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger designates Garhwali as a language which is in the unsafe category and requires consistent conservation efforts.[8]

Almost all people who can speak and understand Garhwali can also speak and understand Hindi, one of the most commonly spoken languages of India.

Development of Garhwali

In the middle period of the course of development of Indo-Aryan languages, there were many prakrit. Of these, the "Khas Prakrit" is believed to be the source of Garhwali[9][10] . The early form of Garhwali can be traced to the 10th century which is found in numismatics, royal seals, inscriptional writings on copper plates and temple stones containing royal orders and grants. One such early example is the temple grant inscription of King Jagatpal at Dev Prayag (1335 AD). Most of the Garhwali literature is preserved in folk form, handed down verbally from generation to generation but since the 18th century, literary traditions are flourishing.[11] Till the 17th century, Garhwal was always a sovereign nation under the Garhwali Kings.[12] Naturally, Garhwali was the official language of the Garhwal Kingdom[12] for hundreds of years under the Panwar (Shah) Kings and even before them, until the Gurkhas captured Garhwal and subsequently the British occupied half of Garhwal, later called British Garhwal which was included under the United Province. Garhwal Kingdom acceded to the Union of India as a part of Uttar Pradesh in 1949.

Garhwali Dialects

- Srinagariya (सिरिनगरिया) – classical Garhwali spoken in erstwhile royal capital, Srinagar, accepted as Standard Garhwali by most scholars.[13]

- Tihriyali (टीरियाळि)/Gangapariya (गंगपरिया) – spoken in Tehri Garhwal.

- Badhani (बधाणी)- spoken in Chamoli Garhwal.

- Dessaulya(दसौल्या)

- Lohabbya (लोहब्या)

- Majh-Kumaiya (मांझ-कुमैया)- spoken at the border of Garhwal and Kumaon.

- Nagpuriya (नागपुर्या)- spoken in Rudraprayag district.

- Rathi (राठी)- spoken in Rath area of Pauri Garhwal.

- Salani (सलाणी)- spoken in Talla Salan, Malla Salan and Ganga Salan parganas of Pauri.

- Ranwalti (रंवाल्टी)- spoken in Ranwain (रंवाँई), the Yamuna valley of Uttarkashi.

- Bangani (बंगाणी)- spoken in Bangaan (बंगाण) area of Uttarkashi.

- Parvati – reportedly not mutually intelligible with other dialects.

- Jaunpuri (जौनपुरी)- spoken in Uttarkashi and Tehri districts.

- Gangadi (गंगाड़ी) (spoken in Uttarkashi)

- Chaundkoti चौंदकोटी- spoken in Pauri.

(Linguistically unrelated but geographically neighbouring languages include: the Tibeto-Burman language Marchi/Bhotia – spoken by Marchas, neighbouring Tibet.)

Dialects & Standard Garhwali

- Standard Garhwalis & more of its dialects have an accusative case सणि (/səɳi/) while South Garhwalis dialects have different word ते (/te/) for accusative case ( Maybe borrowed from Awadhi or Braj). But in Standard Garhwali or High Garhwali ते is used as oblique case.

- Standard Garhwalis & West Garhwalis dialects have an allophonic feature where aspirated voiceless alveolar stop थ /tʰə/ converts into voiceless dental stop त़ (t̪). Southern dialects almost lost the feature.

Sources of vocabulary

The basic vocabulary and language of primitive Garhwali is said to have been developed on the language used by the inhabitants of the pre-historic age belonging to Negrito Australoid, Dravidian and Mongoloid ethnic groups.[14] These are primarily the Munda, Bhil, Naag, Yaksha, etc. The other non-Aryan tribes from the Northwest, such as Kunind, Kirat, Shak, Hun, Gurjar, Pisach, Darad also contributed to its vocabulary and influenced the language. The languages of the powerful Khasas, who still form a majority in Garhwal, is believed to be the source of Garhwali language.[12] The later Aryans with their Vedic Sanskrit and Prakrit languages helped in adding to the vocabulary. Subsequently, Saurseni and Rajasthani Apbhransha had considerable influence in shaping the Garhwali Language. During the Medieval period, due to increasing interaction with outside regions, Punjabi, Rajasthani, Gujarati, Marathi, Bengali words also crept into the repertoire of spoken Garhwali. Contact with the Delhi rulers resulted in intrusion of Persian, Arabic, Turkish and English words. From the 18th century, however, Hindi started exerting the maximum impact, not only on enriching the vocabulary, but also on the grammatical formation and syntax of the Garhwali language. Nevertheless, more than one third of the vocabulary remained of native base and indigenous structure.

Grammar

Being part of the Indo-Aryan languages, Garhwali shares many elements of its grammar with other Indo-Aryan languages, especially Rajasthani, Kashmiri and Gujarati. It shares much of its grammar with the other Pahari languages like Kumaoni and Nepali. The peculiarities of grammar in Garhwali and other Central Pahari languages exist due to the influence of the ancient language of the Khasas, the first recorded inhabitants of the region and the root of Garhwali language.

In Garhwali the verb substantive is formed from the root ach, as in both Rajasthani and Kashmiri. In Rajasthani its present tense, being derived from the Sanskrit present rcchami, I go, does not change for gender. But in Pahari and Kashmiri it must be derived from the rare Sanskrit particle *rcchitas, gone, for in these languages it is a participial tense and does change according to the gender of the subject. Thus, in the singular we have: – Here we have a relic of the old Khasas language, which, as has been said, seems to have been related to Kashmiri. Other relics of Khasa, again agreeing with north-western India, are the tendency to shorten long vowels, the practice of epenthesis, the modification of a vowel by the one which follows in the next syllable, and the frequent occurrence of de-aspiration. Thus, Khas – siknu, Garhwali – sikhnu, but Hindi – sikhna, to learn; Garhwali – inu, plural – ina, of this kind.

| Khas-Kura | Garhwali | Kashmiri | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Masc | Fem | Masc | Fem | Masc | Fem |

| Am | छु | चु | छौं | छौं | थुस | छेस |

| Are | छस | छेस | छैं/छै/छन | छैं/छै/छन | छुख | छेख |

| Is | छ | छे | छ/च | छ/च | छुह | छेह |

Linguistics

Morphology

Garhwali Pronouns

| Nominative | Oblique | Reflexive | Possessive determiner | Possessive pronoun | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st pers. sing. | मी | म्येते | म्यर | म्ये | |

| 2nd pers. sing./pl. | तुम | त्वे/तुमते | तुमुर | त्वे or तुमौ | |

| 3rd pers. sing. | व, उ, इ, सि | वीँ, वे, ए, से | वीँ, वे, ए, से | वीँ, वे, ए, से | |

| 1st pers. pl. | हम | हमते | हमर | हमौ | |

| 3rd pers. pl. | उ | उँते | उँ | ऊँ |

Garhwali Cases

| Written | Spoken (Low Speed) | Spoken (fluently) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | न/ल | न/ल | न्/ल् |

| Vocative | रे | रे | रे |

| Accusative | थे/थेकी/सणि | थे/थेकी/सणि | ते/ते/सन् |

| Instrumental | न/ल/चे | न/ल/चे | न्/ल्/चे |

| Dative | खुण/बाना | कुन/बाना | कु/बान् |

| Ablative | न/ल/चे/मनन/चुले/बटिन | न/ल/चे/मनन/चुले/बटिन | न्/ल्/चे/मनन्/चुले/बटि |

| Genitive | ऑ/ई/ऊ/ऎ | ऑ/ई/ऊ/ऎ | ऑ/ई/ऊ/ऎ |

| Locative | म/फुण्ड/फर | म/फुण्/फर | म्/पुन्/पर् |

Numerals

| Number | Numeral | Written | RTGS | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ० | सुन्ने | sunne | /sunnɨ/ |

| 1 | १ | यऽक | yak | /yʌk/ |

| 2 | २ | दुई | dui | /du’ī/ |

| 3 | ३ | तीन | teen | /tɪnə/ |

| 4 | ४ | चार | char | /carə/ |

| 5 | ५ | पाँच | paanch or paa~ | /pʌ~ç/ or //pʌ~/ |

| 6 | ६ | छॉ | chhaw | /tʃʰɔ/ |

| 7 | ७ | सात | saat | /sʌtə/ |

| 8 | ੮ | आठ | aath | /a:ṭə/ |

| 9 | ९ | नउ | nau | /nəu/ |

Phonology

There are many differences from Hindi and other Indic languages, for example in the palatal approximant /j/, or the presence of a retroflex lateral /ɭ/. Garhwali also has different allophones.

Phone or Phoneme

Vowels

Monophonic vowels

There are many theories used to explains how many Monophthongs are used in the Garhwali language. The Non-Garhwali Indian scholars with some Garhwali scholars (who believes Garhwali as a dialect of Hindi) who follows Common Hindustani phonology argue that there are eight vowels found within the language are ə, ɪ, ʊ, ɑ, i, u, e, o. A Garhwali language scholar Mr. Bhishma Kukreti argues that /ɑ/ is not present in the language instead of it long schwa i.e. /ə:/ is used. Although it can be accepted that southern Garhwali dialects have uses of /ɑ/ instead /ə:/. If we follow his rule of vowel length we found that there are five vowels found in Garhwali. The three are ə, ɪ, ʊ with their vowel length as /ə:/, /ɪ:/, /ʊ:/. Other two /o/ & /e/ with no vowel length. But there are 13 vowels founded by Mr. Anoop Chandra Chandola[15] as follows /ə/, /ɪ/, /ʊ/, /ɑ/, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /æ/, /ɨ/, /y/, /ɔ/, /ɯ/. His arguments can be accepted as universal (also /ɑ/ which is used only in Southern dialects but borrowed to Standard dialect for distinction purposes) . But Bhishma Kukreti's argument about vowel length is also accepted. Hence we concluded that Garhwali (Standard Garhwali in this mean) has twelve vowels (/ə/, /ɪ/, /ʊ/, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /æ/, /ɨ/, /y/, /ɔ/, /ɯ/) where three has vowel length (/ə:/, /ɪ:/, /ʊ:/).

Diphthongs

There are Diphthongs in the language which makes the words distinctive than other. However diphthongs vary dialect by dialect.

| Diphthongs (IPA) | Example (IPA) | Glos |

|---|---|---|

| उइ /ui/ | कुइ /kui/ | anybody |

| इउ /iu/ | जिउ /ʤiu/ | Heart, mind |

| आइ /ai/ | बकाइ /bəkɑi/ | After-all, besides |

| अइ /əi/ | बकइ /bəkəi/ | Balance |

| आउ /au/ | बचाउ /bətʃou/ | Save (verb) |

| अउ /əu/ | बचउ /bətʃəu/ | Safty |

Triphthongs

Triphthongs are less commonly found in the language. The most common word where a triphthong may occur is ह्वाउन [English: may be] /hɯɔʊn/ (in standard Garhwali) or /hɯaʊn/ (in some dialects). However many speakers can't realize the presence of triphthongs. Other triphthongs might be discovered if more academic research were done on the language.

Consonants

Tenuis consonants

| GPA (Garhwali Phonetic Alphabet) /IPA / | Phoneme /IPA alternate/ | Phonemic category | Example /<IPA Alternate>/ (<Description>) | Hindustani language alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| क /kə/ | क् /k/ | voiceless velar stop or voiceless velar plosive | कळ्यो /kaɭyo/ (Literary meaning:- Breakfast) | नाश्ता, कलेवा |

| ग /gə/ | ग् /g/ | voiced uvular stop or voiced uvular plosive | गरु /gərʊ/ (Literary meaning:- Heavy weight) | भारी |

| च /tʃə/ | च् /tʃ/ | voiceless palato-alveolar affricate or voiceless palato-alveolar sibilant affricate or voiceless domed postalveolar sibilant affricate | चिटु /tʃiʈɔ/ (Literary meaning:- White; masculine) | सफ़ेद, श्वेत |

| ज /ʤə/ | ज् /ʤ/ | voiced alveolar sibilant affricate | ज्वनि /ʤɯni/ (Literary meaning:- Youngage) | जवानी, यौवन |

| ट /ʈə/ | ट् /ʈ/ | voiceless retroflex stop | टिपुण् /ʈɨpɯɳ/ (Literary meaning:- to pick; a verb) | चुगना, उठाना |

| ड /ɖə/ | ड् /ɖ/ | voiced retroflex stop | डाळु /ɖɔɭʊ/ (standard) or /ɖaɭʊ/ (in some southern dialects),(Literary meaning:- Tree) | डाल, पेड़, वृक्ष |

| त /tə/ | त् /t/ | voiceless alveolar stop | तिमुळ /tɨmɯɭ/ ,(Literary meaning:- Moraceae or Fig; a fruit) | अञ्जीर/अंजीर |

| द /də/ | द् /d/ | voiced alveolar stop | देस /deç/ ,(Literary meaning:- Foreign) [don't be confused with देस /des/; meaning "country" borrowed from Hindustani] | विदेश, परदेस, बाहरला-देस |

| प /pə/ | प् /p/ | voiceless bilabial stop | पुङ्गुड़ु /pʊŋuɽ, (Literary Meaning:- Farm or Field) | खेत or कृषि-भुमि |

| ब /bə/ | ब् /b/ | voiced bilabial stop | बाच /batʃə, (Literary Meaning:- Tongue, Phrasal & other meaning:- Voice) | जीभ, जुबान, आवाज़ |

| ल /lə/ | ल् /l/ | dental, alveolar and postalveolar lateral approximants | लाटु /lʌʈɔ/ (Literary meaning:- idiot or mad or psycho; when used in anger. insane; when used in pity or love) | झल्ला, पागल |

| ळ /ɭə/ | ळ् /ɭ/ | retroflex lateral approximant | गढ़वाळ् /gəɖwɔɭ/ (Literary meaning:- One who holds forts,Generally used for the land of Garhwallis People,or Garhwal) | गढ़वाल |

| य /jə/ | य् /j/ | Palatal approximant | यार /jar/ (Literary meaning:- Friend, commonly used as vocative word) | यार |

| व /wə/ | व् /w/ | Voiced labio-velar approximant | बिस्वास /biswɔs/ (Literary meaning: Faith) | विश्वास, भरोसा |

| म /mə/ | म् /m/ | bilabial nasal | मुसु /mʊs/ (Literary meaning: Mouse) | मूषक, चुहा |

| न /nə/ | न् /n/ | alveolar nasal | निकम् /nɨkəm/ (Literary meaning:- Useless, Worthless) | बेकार, व्यर्थ |

| ण /ɳə/ | ण् /ɳ/ | retroflex nasal | पाणि /pæɳ/ (Literary meaning:- Water) | पानी |

| ङ /ɳə/ | ङ् /ɳ/ | velar nasal | सोङ्ग or स्वाङ्ग /sɔɳ/ (Literary meaning:- Easy) | सरल, आसान |

| ञ /ɲə/ | ञ् /ɲ/ | palatal nasal | फञ्चु /pʰəɲtʃɔ/ (Literary meaning:- Bundle or Bunch) | पोटली |

Aspirated consonants

य्, र्, ल्, ळ्, व्, स् and the nasal consonants (म्, न्, ञ्, ङ्, ण्) have no aspirated consonantal sound.

| Alphabet /<IPA alternate>/ | Phoneme /<IPA alternate>/ | Example /<IPA alternate>/ (<Description>) | Hindustani language alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|

| ख /kʰə/ | ख् /kʰ/ | खार्यु /kʰɔryʊ/ (Literary meaning:- Enough, Sufficient) | नीरा, पर्याप्त, खासा |

| घ /gʰə/ | घ् /gʃʰ/ | घंघतौळ /gʰɔŋgtoɭə/ (Literary meaning:- Confusion) | दुविधा |

| छ /tʃʰə/ | छ् /tʃʰ/ | छज्जा /tʃʰəʤə/ (Literary meaning:- Balcony,Gallery) | ओलती, छज्जा |

| झ /dʒʰə/ | झ् /dʒʰ/ | झसक्याण /dʒʰəskæɳ/ (Literary meaning:- to be scared) | डर जाना |

| थ /tʰə/ | थ् /tʰ/ | थुँथुरु /tʰɯ~tʊr/ (Literary meaning: Chin) | ठोड़ी |

| ध /dʰə/ | ध् /dʰ/ | धागु /dʰɔgʊ/ (Literary meaning: Tag or thread) | धागा |

| ठ /ʈʰə/ | ठ् /ʈʰ/ | ठुङ्गार /ʈʰɯɳʌr/ (Literary meaning: Snacks) | स्नैक्स्, नमकीन |

| ढ /ɖʰə/ | ढ् /ɖʰ/ | ढिकणु /ɖʰikəɳʊ/ (Literary meaning: Coverlet) | ओढने की चादर |

| फ /pʰə/ | फ् /pʰ/ | फुकाण /pʰʊkaɳ/ (Literary meaning:- Destruction) | नाश |

| भ /bʰə/ | भ् /bʰ/ | भौळ or भ्वळ /bʰɔɭə/ (Literary meaning:- Tomorrow) | कल (आने वाला) |

Allophony

The Garhwali speakers are most familiar with allophones in the Garhwali language. For example, फ (IPA /pʰ/) is used as फ in the word फूळ (IPA /pʰu:ɭ/ English: flower) but pronounced as प (IPA /p/) in the word सफेद (IPA /səpet/, English: "white").

Allophones of aspirated consonants

Conversion to tenuis consonant or loss of aspiration

Almost every aspirated consonant exhibits allophonic variation. Each aspirated consonant can be converted into the corresponding tenuis consonant. This can be called loss of aspiration.

| Alphabet /IPA/ | Phoneme /IPA/ | Allophone /IPA/ | Example /IPA/ (Description) | Hindustani language alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ख /kʰə/ | ख् /kʰ/ | क् /k/ | उखरेण /ukreɳ/ (Literary meaning:- pass away or die) | गुजर जाना |

| घ /gʰə/ | घ् /gʰ/ | ग् /g/ | उघड़ण /ugəɽɳ/ (Literary meaning:- to open or to release) | खोलना, विमोचन |

| थ /tʰə/ | थ् /tʰ/ | त् /t/ | थुँथुरु /tʰɯ~tʊr/ (Literary meaning:- Chin) | ठोड़ी |

| फ /pʰə/ | फ् /pʰ/ | प् /p/ | उफरण /upə:ɳ/ (Literary meaning:- to unbind or to undo or to unlace) | खोलना, विमोचन (बंधी हुइ चीज़ को खोलना) |

Allophone of छ

| Alphabet /<IPA alternate>/ | Phoneme /<IPA Alternate>/ | Allophone | Example /<IPA Alternate>/ (<Description>) | Hindustani Language Alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| छ /tʃʰə/ | छ् /tʃʰ/ | स़् /ç/ | छन्नी /çə:ni/ (Literary meaning:- Shed; but used specially for cattle-shed, some southern dialects sometime use छ as an pure phonem so words like छन्नी pronounced as छन्नी or as स़न्नी) | छावनी,पशु-शाला |

| छ /tʃʰə/ | छ् /tʃʰ/ | च़् /c/ | छ्वाड़ /cɔɽ/ (Literary meaning:- Bank, Side) | छोर, किनारा |

Allophones of tenuis consonants

Conversion from voiced to voiceless consonant

A few of the tenuis consonants have allophonic variation. In some cases, a voiced consonant can be converted into the corresponding voiceless consonant.

| Alphabet /<IPA alternate>/ | Phoneme /<IPA Alternate>/ | Allophone | Phonemic Category of Allophone | Example /<IPA Alternate>/ (<Description>) | Hindustani Language Alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ग /gə/ | ग् /g/ | क् /k/ | voiceless velar stop | कथुग /kətuk/ ,(Literary meaning:- How much) | कितना |

| द /də/ | द् /d/ | त् /t/ | Voiceless alveolar stop | सफेद /səpet/ ,(Literary meaning:- White) | सफेद |

| ड् /ɖə/ | ड् /ɖ/ | ट् /ʈ/ | Voiceless retroflex stop | परचण्ड /pərətʃəɳʈ/ ,(Literary meaning:- fierce) | प्रचण्ड |

| ब /bə/ | ब् /b/ | प् /p/ | voiceless bilabial stop | खराब /kʰərap/ ,(Literary meaning:- Defective) | खराब |

Other allophones

| Alphabet /<IPA alternate>/ | Phoneme /<IPA alternate>/ | Allophone | Phonemic category of allophone | Example /<IPA alternate>/ (<Description>) | Hindustani language alternate of the word |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ज /ʤə/ | ज् /ʤ/ | य़् /j/ | voiced palatal approximant | जुग्गा /jɯggə/ ,(Literary meaning:- Able) | योग्य, क़ाबिल |

| स /sə/ | स् /s/ | स़् /ç/ | voiceless palatal fricative | (a) सि /çɨ/ (Literary meaning:- This), (b) देस /deç/ (Literary meaning:- Foreign) | (a) यह (b)बाहरला-देस, परदेस |

| च /tʃə/ | च् /tʃ/ | च़् /c/ | voiceless palatal stop | चाप /capə/ (Literary meaning:- Anger) | कोप, गुस्सा |

In grammatical numbers

| Singular (written) /IPA/ | Singular (spoken) | Plural (written and spoken) |

|---|---|---|

| किताब /kitʌb/ | किताप /kitʌp/ | कितबि /kitəbi/ |

| जुराब /ʤurʌb/ | जुराप /ʤurʌp/ | जुरबि /ʤurəbi/ |

Assimilation

Garhwali exhibits deep Assimilation (phonology) features. Garhwali has schwa deletion during sandhi, as in Hindi, but in other assimilation features it differs from Hindi. An example is the phrase राधेस्याम. When we write this separately, राधे & स्याम (IPA:- /rəːdʰe/ & /syəːm/) it retains its original phonetic feature, but when assimilated it sounds like रास्स्याम /rəːssyəːm/ or राद्स़्याम /rəːdçyəːm/.

Garhwali literature

Garhwali has a rich literature in all genres including poetry, novels, short stories and plays.[14] Earlier, Garhwali literature was present only as folklore. Although Garhwali was the official language of the Kingdom of Garhwal since 8th century, the language of literature was mostly Sanskrit. The oldest manuscript that has been found is a poem named "Ranch Judya Judige Ghimsaan Ji" written by Pt. Jayadev Bahuguna (16th century). In 1828 AD, Maharaja Sudarshan Shah wrote "Sabhaasaar". In 1830 AD, American missionaries published the New Testament in Garhwali. Thereafter, Garhwali literature has been flourishing despite government negligence. Today, newspapers like "Uttarakhand Khabarsar" and "Rant Raibaar" are published entirely in Garhwali.[16] Magazines like "Baduli", "Hilaans", "Chtthi-patri" and "Dhaad" contribute to the development of the Garhwali language. Some of the important Garhwali writers and their prominent creations are:

- Abodhbandhu Bahuguna – "Ankh-Pankh", "Bhoomyal" and "Ragdwaat"

- Atmaram Gairola

- Ravindra Dutt Chamoli

- Bachan Singh Negi – "Garhwali translation of Mahabharat and Ramayan"

- Baldev Prasad Din (Shukla) "Bata Godai kya tyru nau cha" (Garhwali Nirtya-natika)

- Beena Benjwal – "Kamedaa Aakhar"

- Bhagbati Prasad Panthri – "Adah Patan" and "Paanch Phool"

- Bhajan Singh 'Singh' – "Singnaad"

- Bhawanidutt Thapliyal – "Pralhad"

- Bholadutt Devrani – "Malethaki Kool"

- Bijendra Prasad Naithani "Bala Sundari Darshan", "Kot Gaon Naithani Vanshawali", "Ristaun ki Ahmiyat", "Chithi-Patri-Collection"

- Chakradhar Bahuguna – "Mochhang"

- Chandramohan Raturi – "Phyunli"

- Chinmay Sayar – "Aunar"

- Dr. Narendra Gauniyal – "Dheet"

- Dr. Shivanand Nautiyal

- Durga Prasad Ghildiyal – "Bwari", "Mwari" and "Gaari"

- Gireesh Juyal 'Kutaj' – "Khigtaat"

- Govind Chatak – "Kya Gori Kya Saunli"

- Harsh Parvatiya – "Gainika nau par"

- Jayakrishna Daurgadati – "Vedant Sandesh"

- Jayanand Khugsaal – "Jhalmatu dada"

- Kanhaiyyalal Dandriyal – "Anjwaal"

- Keshavanand Kainthola – "Chaunphal Ramayan"

- Lalit Keshwan – "Khilda Phool Hainsda Paat", "Hari Hindwaan"

- Lalit Mohan Thapalyal – "Achhryun ku taal"

- Leeladhar Jagudi – "Poet & Writer & Novelist"

- Lokesh Nawani – "Phanchi"

- Madan Mohan Duklaan – "Aandi-jaandi saans"

- Mahaveer Prasad Gairola – "Parbati"

- Pratap Shikhar – "Kuredi phategi"

- Premlal Bhatt – "Umaal"

- Purushottam Dobhal

- Sadanand Kukreti

- Satyasharan Raturi – "Utha Garhwalyun!"

- Shreedhar Jamloki – "Garh-durdasa"

- Sudaama Prasad Premi – "Agyaal"

- Sulochana Parmar

- Taradutt Gairola – "Sadei"

- Virendra Panwar – "Inma kankwei aan basant"(Poetry)"Been(critic)Chween-Bath(interview)Geet Gaun Ka(Geet)

- Vishalmani Naithani "Chakrachal", "Kauthik", "Beti Buwari", "Pyunli Jwan Hwegi", "Matho Singh Bhandari Nirtya Natika", "Meri ganga holi ta mai ma bauri aali", "Jeetu Bagdwal", etc. scripts writer.

In 2010, the Sahitya Akademi conferred Bhasha Samman on two Garhwali writers: Sudama Prasad 'Premi' and Premlal Bhatt.[17] The Sahitya Akademi also organized "Garhwali Bhasha Sammelan"(Garhwali Language Convention) at Pauri Garhwal in June 2010.[18] Many Garhwali Kavi Sammelan (poetry readings) are organized in different parts of Uttarakhand and, in Delhi and Mumbai.[19]

Usage

In media

In the last few decades Garhwali folk singers like Narendra Singh Negi, Preetam Bhartwan and many more have roused people's interest in the Garhwali language by their popular songs and videos. On average there is one movie in four or five years in Garhwali. Anuj Joshi (Hindi: अनुज जोशी) is one of the prominent Garhwali film director.

In order to create a folk genome tank of Uttarakhand where one can find each genre and occasions in the form of folk music, and to bring the melodious folk from the heart of Himalaya to the global screen, the very first Internet radio of Kumaon/Garhwal/Jaunsar was launched in 2008 by a group of non-resident Uttarakhandi from New York, which has been gaining significant popularity among inhabitants and migrants since its beta version was launched in 2010. This was named after a very famous melody of the hills of Himalaya, Bedupako Baramasa O Narain Kafal Pako Chaita Bedupako[20]

Debates concerning the classification of the Bangani dialect

The Bangani dialect of Garhwali is of interest amongst scholars of Indo-European languages, due to some unusual features.

Since the 1980s, Claus-Peter Zoller – a scholar of Indian linguistics and literature – claimed that there was a centum language substrate in the Bangani dialect. Zoller has also suggested that Bangani has been misclassified as a dialect of Garhwali and is more closely related to the Western Pahari languages.

The substance of Zoller's claims has been rejected by George van Driem and Suhnu Sharma, in publications since 1996,[21] which claim that Zoller's data was flawed and that Bangani is an unambiguously satem language.

Zoller does not accept the findings by van Driem and Sharma.[22][23] Other linguists, such as Anvita Abbi and Hans Henrich Hock, have also offered some support for Zoller's hypothesis.[24]

Comparative analysis with other Indian languages

Comparison with Hindi

Garhwali is a language like Hindi is. Most Hindi scholars call it a dialect of Hindi, but Garhwali differs from Hindi in various aspects of its phonology, morphology, semantics and syntax. Here are some examples of the features that make Garhwali different from Hindi.

Using Instrumental & Ablative cases & degrees

Garhwali language has more specific words used for the instrumental and ablative cases and degrees while Hindi has only one. Here are the examples shown:

| Feature | Garhwali /IPA/ | Hindi /IPA/ | English | Example | Translation in English | Translation in Hindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Degree | चुले /tʃule/ | से /se/ | Greater than | चैतु मि चुले बोळ्या च | Chetu is stupider than me. | चैतु मुझसे झल्ला है. |

| Superlative Degree | मनन /mənən/ | से /se/ | Greatest | मी छौं सब मनन ग्वरु | I am fairest. | मैं सबसे गोरा हूं |

| बटिन /bəʈɨn/ | से /se/ | From | मी ब्यळी दिल्ली बटिन औं | I came from Delhi yesterday | मैं कल दिल्ली से आया | |

| चे //tʃɪ/ | से /se/ | By | सि मि चे ह्वाइ | It is done by me. | यह मुझ से हुआ | |

| मुङ्गे or मुंगे // |

Comparison with Gujrati

Due to Brahmin migration from Gujarat region Garhwali is also influenced by Gujarati. The most similar feature in both languages is using of ār in Gujarati & ɪr like suffix er is used in English for person's relation with its object of occupation.

Official recognition

Although Garhi is the most spoken language of Uttarakhand, the state government has not recognised it yet. After long-standing demands to make it the official language of Uttarakhand and to be taught at schools and universities,[25] the state government issued orders to introduce Kumaoni and Garhwali languages at the Kumaon University at the undergraduate level.[26] At the national level, there are constant demands to include Garhwali in the 8th schedule of the Constitution of India so that it could be made one of the Scheduled Language of India.[27][28] Recently, a Member of Parliament from Pauri Garhwal, Satpal Maharaj brought a private member's bill to include Garhwali language in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution, which is being debated in the Lok Sabha.[29]

See also

Further reading

- Upreti, Ganga Dutt (1894). Proverbs & folklore of Kumaun and Garhwal. Lodiana Mission Press.

- Govind Chatak-"Garhwali bhasha", Lokbharti Prakashan, Dehradun, 1959.

- Haridutt Bhatt 'Shailesh'- "Garhwali bhasha aur uska sahitya", Hindi Samiti, UP, 1976.

- Abodhbandhu Bahuguna- "Garhwali bhasha ka vyakaran", Garhwali Prakashan, New Delhi.

- Rajni Kukreti- "Garhwali bhasha ka Vyakaran", Winsar Pub.,Dehradun,2010.

- Govind Chatak- "Garhwali Lokgeet", Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 2000.

- Yashwant Singh Kathoch- "Uttarakhand ka Naveen Itihaas", Winsar Pub, Dehradun, 2006.

- Pati Ram Bahadur- "Garhwal:Ancient and Modern", Pahar Publications, 2010.

- Bachan Singh Negi – "Ramcharitmanas, Sreemad Bhagwat Geeta" – Garhwali translations, Himwal Publications, Dehradun, 2007.

References

- ↑ Garhwali at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ↑ "Census of India: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues –2001". censusindia.gov.in.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Garhwali". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Garhwali. A language of India". Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "India languages". We make learning fun. Hindikids.

- ↑ "Sensus Data Online http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Language/Statement1.htm.". We make learning fun. Hindikids. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Claus-Peter Zoller (March 1997). "Garhwali. A language of India". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ Yashwant Singh Kathoch- "Uttarakhand ka naveen itihaas", Winsar Pub, Dehradun, 2006.

- ↑ Bhajan Singh 'Singh'- "Garhwali Bhasha aur Sahitya","Garhwal aur Garhwal", Winsar Publications, Pauri, 1997.

- ↑ http://www.kavitakosh.org/kk/index.php?title=%E0%A4%97%E0%A4%A2%E0%A4%BC%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B2%E0%A5%80_%E0%A4%B2%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%80%E0%A4%A4

- 1 2 3 Yashwant Singh Kathoch- "Uttarakhand ka Naveen Itihaas", Winsar Publications, Dehradun, 2006.

- ↑ "Garhwali". Ethnologue.

- 1 2 Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chandola, Anoop Chandra. "Animal Commands of Garhwali and their Linguistic Implications". WORD. 19 (2): 203–207. doi:10.1080/00437956.1963.11659795.

- ↑ http://www.nainitalsamachar.in/ten-years-of-uttarakhand-khabar-sar/

- ↑ http://www.navhindtimes.in/iexplore/recognising-hidden-talent

- ↑ http://www.nainitalsamachar.in/garhwali-kumaoni-language-can-be-part-of-eighth-schedule/

- ↑ Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dr. Shailesh Upreti (23 February 2011). "First e Radio of Uttarakhand". official. bedupako. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ↑ "Religion and Global empire". The Newsletter Issue 54. International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS). Archived from the original on 19 October 2006. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "The van Driem Enigma Or: In search of instant facts". Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "?".

- ↑ Hans Henrich Hock & Elena Bashir, The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Comprehensive Guide, Berlin/Boston, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, p. 9n.

- ↑ http://www.nainitalsamachar.in/garhwali-kumaoni-language-should-be-in-eighth-schedule/

- ↑ "Kumaoni, Garhwali languages on university 2014-15 syllabi", The Times of India

- ↑ Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 27 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Garhwali language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |