Gurjara-Pratihara

| Gurjara-Pratihara | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

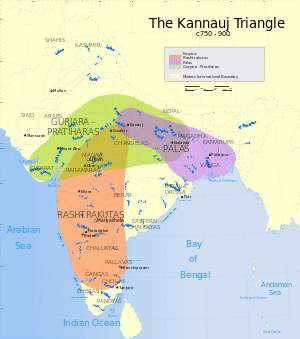

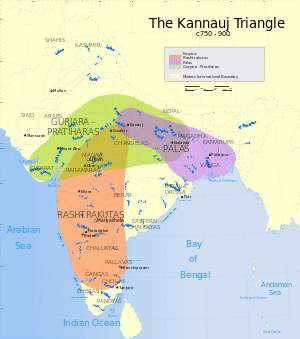

Extent of the Pratihara Empire shown in green | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kannauj | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Sanskrit, Prakrit | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Classical India | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | mid-7th century CE | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Conquest of Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni | 1008 CE | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1036 CE | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||||||

The Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty, also known as the Pratihara Empire, was an Indian imperial power that ruled much of Northern India from the mid-7th to the 11th century. They ruled first at Ujjain and later at Kannauj.[1]

The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River.[2] Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid and Tamin during the Caliphate campaigns in India. Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India. Nagabhata II was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly, and was succeeded by his son Mihira Bhoja. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Pratihara Empire reached its peak of prosperity and power. The extent of its territory rivaled that of the Gupta Empire, by the time of Mahendrapala, the empire reached west to the border of Sindh, east to Bengal, north to the Himalayas, and south past the Narmada.[3][4] The expansion once again triggered the power struggle for the control of the Indian Subcontinent, known as the Tripartite Struggle, with the Rashtrakuta Empire and Pala Empire. During this period, Imperial Pratihara took the title Maharajadhiraja of Āryāvarta (Great King of Kings of Northern India).

Gurjara-Pratihara are known for their sculptures, carved panels and open pavilion style temples. The greatest development of Gurjara-Pratihara style of temple building took place at Khajuraho (a UNESCO World Heritage Site).[5]

The power of the Pratiharas was weakened by dynastic strife. It was further diminished as a result of a great raid from the Deccan, led by the Rashtrakuta ruler Indra III, who about 916 sacked Kannauj. Under a succession of rather obscure rulers, the Pratiharas never regained their former influence. Their feudatories became more and more powerful, one by one throwing off their allegiance until by the end of the 10th century the Pratiharas controlled little more than the Gangetic Doab. Their last important king, Rajyapala, was driven from Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1018.[4]

Etymology and origin

_from_Nilgund_of_Rashtrakuta_King_Amoghavarsha_I.jpg)

The origin of the dynasty and the meaning of the term "Gurjara" in its name is a topic of debate among historians. The rulers of this dynasty used the self-designation "Pratihara" for their clan, and never referred to themselves as Gurjaras.[6] The Imperial Pratiharas could have emphasized their Kshatriya, instead of Gurjara, identity for political reasons. However, at local levels Pratiharas were not wary of projecting their tribal (Gurjara) identity.[7] They claimed descent from the legendary hero Lakshmana, who is said to have acted as a pratihara ("door-keeper") for his brother Rama.[8][9] K. A. Nilakanta Sastri theorized that the ancestors of the Pratiharas served the Rashtrakutas, and the term "Pratihara" derives from the title of their office in the Rashtrakuta court.[10]

Multiple inscriptions of their neighbouring dynasties describe the Pratiharas as "Gurjara".[11] The term "Gurjara-Pratihara" occurs only in the Rajor inscription of a feudatory ruler named Mathanadeva, who describes himself as a "Gurjara-Pratihara". Another Pratihara king named Hariraja is also mentioned as a "ferocious Gurjara" (garjjad gurjjara meghacanda) in the Kadwaha inscription. [12] According to one school of thought, Gurjara was the name of the territory (see Gurjara-desha) originally ruled by the Pratiharas; gradually, the term came to denote the people of this territory. An opposing theory is that Gurjara was the name of the tribe to which the dynasty belonged, and Pratihara was a clan of this tribe.[13] Several historians consider Gurjaras to be the ancestors of the modern Gurjar or Gujjar tribe. [14] The proponents of the tribal designation theory argue that the Rajor inscription mentions the phrase: "all the fields cultivated by the Gurjaras". Here, the term "Gurjara" obviously refers to a group of people rather than a region.[15][16] The Pampa Bharata refers the Gurjara-Pratihara king Mahipala as a Gurjara king. Rama Shankar Tripathi argues that here Gurjara can only refer to the king's ethnicity, and not territory, since the Pratiharas ruled a much larger area of which Gurjara-desha was only a small part.[15] Critics of this theory, such as D. C. Ganguly, argue that the term "Gurjara" is used as a demonym in the phrase "cultivated by the Gurjaras".[17] Several ancient sources including inscriptions clearly mention "Gurjara" as the name of a country.[18][19][20] Shanta Rani Sharma notes that an inscription of Gallaka in 795 CE states that Nagabhata I, the founder of the Imperial Pratihara dynasty, conquered the "invincible Gurjaras," which makes it unlikely that the Pratiharas were themselves Gurjaras.[21] However, she does concede that Imperial Pratiharas were indeed known as Gurjaras, on account of their nationality. She mentions two groups of people who were known as Gurjaras, and draws a line between them; i.e. Gurjaras who were an ethnic people and Gurjaras who were nationals of Gurjaradesa (Gurjara Country). [22] According to her, Gujjars are the descendants of ethnic Gurjaras, and have nothing to do with imperial Pratiharas and Chalukyas who were also known as Gurjaras (due to their Gurjara nationality). [21]

Among those who believe that the term Gurjara was originally a tribal designation, there are disagreements over whether they were native Indians or foreigners.[23] The proponents of the foreign origin theory point out that the Gurjara-Pratiharas suddenly emerged as a political power in north India around 6th century CE, shortly after the Huna invasion of that region.[24] Critics of the foreign origin theory argue that there is no conclusive evidence of their foreign origin: they were well-assimilated in the Indian culture. Moreover, if they invaded Indian through the north-west, it is inexplicable why would they choose to settle in the semi-arid area of present-day Rajasthan, rather than the fertile Indo-Gangetic Plain.[25]

According to the Agnivansha legend given in the later manuscripts of Prithviraj Raso, the Pratiharas and three other Rajput dynasties originated from a sacrificial fire-pit (agnikunda) at Mount Abu. Some colonial-era historians interpreted this myth to suggest a foreign origin for these dynasties. According to this theory, the foreigners were admitted in the Hindu caste system after performing a fire ritual.[26] However, this legend is not found in the earliest available copies of Prithviraj Raso. It is based on a Paramara legend; the 16th century Rajput bards probably extended the original legend to include other dynasties including the Pratiharas, in order to foster Rajput unity against the Mughals.[27]

History

The imperial Gurjara-Pratihara family that went on to rule Kannauj originally appears to have ruled Ujjayani in the Avanti region. The Jain text Harivaṃśa, which was completed in 783-84 CE, states that Vatsaraja was the king of Avanti.[28] The 871 CE Sanjan copper-plate inscription of the Rashtrakuta ruler Amoghavarsha states that his ancestor Dantidurga (r. 735–756 CE) performed a religious ceremony at Ujjayani. At that time, the king of Gurjara-desha (Gurjara country) acted as his door-keeper (pratihara).[29][30] The usage of the word pratihara seems to be a word play, suggesting that the Rashtrakuta king subdued the Gurjara-Pratihara king who ruling Avanti at that time.[31]

Early rulers

Nagabhata I (730–756) extended his control east and south from Mandor, conquering Malwa as far as Gwalior and the port of Bharuch in Gujarat. He established his capital at Avanti in Malwa, and checked the expansion of the Arabs, who had established themselves in Sind. In this battle (738 CE) Nagabhata led a confederacy of Gurjara-Pratiharas to defeat the Muslim Arabs who had till then been pressing on victorious through West Asia and Iran. Nagabhata I was followed by two weak successors, who were in turn succeeded by Vatsraja (775–805).

Conquest of Kannauj and further expansion

The metropolis of Kannauj had suffered a power vacuum following the death of Harsha without an heir, which resulted in the disintegration of the Empire of Harsha. This space was eventually filled by Yashovarman around a century later but his position was dependent upon an alliance with Lalitaditya Muktapida. When Muktapida undermined Yashovarman, a tri-partite struggle for control of the city developed, involving the Pratiharas, whose territory was at that time to the west and north, the Palas of Bengal in the east and the Rashtrakutas, whose base lay at the south in the Deccan.[32][33] Vatsraja successfully challenged and defeated the Pala ruler Dharmapala and Dantidurga, the Rashtrakuta king, for control of Kannauj.

Around 786, the Rashtrakuta ruler Dhruva (c. 780–793) crossed the Narmada River into Malwa, and from there tried to capture Kannauj. Vatsraja was defeated by the Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty around 800. Vatsraja was succeeded by Nagabhata II (805–833), who was initially defeated by the Rashtrakuta ruler Govinda III (793–814), but later recovered Malwa from the Rashtrakutas, conquered Kannauj and the Indo-Gangetic Plain as far as Bihar from the Palas, and again checked the Muslims in the west. He rebuilt the great Shiva temple at Somnath in Gujarat, which had been demolished in an Arab raid from Sindh. Kannauj became the center of the Gurjara-Pratihara state, which covered much of northern India during the peak of their power, c. 836–910.

Rambhadra (833-c. 836) briefly succeeded Nagabhata II. Mihira Bhoja (c. 836–886) expanded the Pratihara dominions west to the border of Sind, east to Bengal, and south to the Narmada. His son, Mahenderpal I (890–910), expanded further eastwards in Magadha, Bengal, and Assam.

Decline

Bhoj II (910–912) was overthrown by Mahipala I (912–914). Several feudatories of the empire took advantage of the temporary weakness of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to declare their independence, notably the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand, the Kalachuris of Mahakoshal, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Chauhans of Rajputana. The south Indian Emperor Indra III (c. 914–928) of the Rashtrakuta dynasty briefly captured Kannauj in 916, and although the Pratiharas regained the city, their position continued to weaken in the 10th century, partly as a result of the drain of simultaneously fighting off Turkic attacks from the west, the attacks from the Rashtrakuta dynasty from the south and the Pala advances in the east. The Gurjara-Pratiharas lost control of Rajasthan to their feudatories, and the Chandelas captured the strategic fortress of Gwalior in central India around 950. By the end of the 10th century the Gurjara-Pratihara domains had dwindled to a small state centered on Kannauj.

Mahmud of Ghazni captured Kannauj in 1018, and the Pratihara ruler Rajapala fled. He was subsequently captured and killed by the Chandela ruler Vidyadhara.[34][35] The Chandela ruler then placed Rajapala's son Trilochanpala on the throne as a proxy. Jasapala, the last Gurjara-Pratihara ruler of Kannauj, died in 1036.

Gurjara-Pratihara art

There are notable examples of architecture from the Gurjara-Pratihara era, including sculptures and carved panels.[36] Their temples, constructed in an open pavilion style, were particularly impressive at Khajuraho.[5]

Caliphate campaigns in India

Junaid, the successor of Qasim, finally subdued the Hindu resistance within Sindh. Taking advantage of the conditions in Western India, which at that time was covered with several small states, Junaid led a large army into the region in early 738 CE. Dividing this force into two he plundered several cities in southern Rajasthan, western Malwa, and Gujarat.

Indian inscriptions confirm this invasion but record the Arab success only against the smaller states in Gujarat. They also record the defeat of the Arabs at two places. The southern army moving south into Gujarat was repulsed at Navsari by the south Indian Emperor Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya dynasty and Rashtrakutas. The army that went east, after sacking several places, reached Avanti whose ruler Nagabhata (Gurjara-Pratihara) trounced the invaders and forced them to flee. After his victory Nagabhata took advantage of the disturbed conditions to acquire control over the numerous small states up to the border of Sindh.

Junaid probably died from the wounds inflicted in the battle with the Gurjara-Pratihara. His successor Tamin organized a fresh army and attempted to avenge Junaid’s defeat towards the close of the year 738 CE. But this time Nagabhata], with his Chauhan and Guhilot feudatories, met the Muslim army before it could leave the borders of Sindh. The battle resulted in the complete rout of the Arabs who fled broken into Sindh with the Gurjara-Pratihara close behind them.

The Arabs crossed over to the other side of the Indus River, abandoning all their lands to the victorious Hindus. The local chieftains took advantage of these conditions to re-establish their independence. Subsequently, the Arabs constructed the city of Mansurah on the other side of the wide and deep Indus, which was safe from attack. This became their new capital in Sindh. Thus began the reign of the imperial Gurjara-Pratiharas.

In the Gwalior inscription, it is recorded that Gurjara-Pratihara emperor Nagabhata "crushed the large army of the powerful Mlechcha king." This large army consisted of cavalry, infantry, siege artillery, and probably a force of camels. Since Tamin was a new governor he had a force of Syrian cavalry from Damascus, local Arab contingents, converted Hindus of Sindh, and foreign mercenaries like the Turkics. All together the invading army may have had anywhere between 10–15,000 cavalry, 5000 infantry, and 2000 camels.

The Arab chronicler Sulaiman describes the army of the Pratiharas as it stood in 851 CE, "The ruler of Gurjars maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs, still he acknowledges that the king of the Arabs is the greatest of rulers. Among the princes of India there is no greater foe of the Islamic faith than he. He has got riches, and his camels and horses are numerous."[37]

Legacy

Historians of India, since the days of Elphinstone, have wondered at the slow progress of Muslim invaders in India, as compared with their rapid advance in other parts of the world. The Arabs possibly only stationed small invasions independent of the Caliph. Arguments of doubtful validity have often been put forward to explain this unique phenomenon. Currently it is believed that it was the power of the Gurjara-Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Muslims beyond the confines of Sindh, their first conquest for nearly three hundred years. In the light of later events this might be regarded as the "Chief contribution of the Gurjara Pratiharas to the history of India".[37]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gurjara-Pratihara. |

- ↑ Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. A History of the Indian-Subcontinent from 7000 BC to AD 1200. New York: Routledge. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-203-08850-0.

Madhyadesha became the ambition of two particular clans among a tribal people in Rajasthan, known as Gurjara and Pratihara. They were both part of a larger federation of tribes, some of which later came to be known as the Rajputs

- ↑ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries. Leiden: BRILL. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- ↑ Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. A History of the Indian-Subcontinent from 7000 BC to AD 1200. New York: Routledge. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-203-08850-0.

- 1 2 Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, p. 146

- 1 2 Partha Mitter, Indian art, Oxford University Press, 2001 pp.66

- ↑ Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Tripathi 1959, p. 223.

- ↑ Puri 1957, p. 7.

- ↑ Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri (1953). History of India. S. Viswanathan. p. 194.

- ↑ Puri 1957, p. 9-13.

- ↑ Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 189.

- ↑ Majumdar 1981, pp. 612-613.

- ↑ Puri 1957, p. 1-18.

- 1 2 Tripathi 1959, p. 222.

- ↑ Ganguly 1935, p. 167.

- ↑ Ganguly 1935, pp. 167-168.

- ↑ Ganguly 1935, p. 168.

- ↑ Puri 1986, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Mishra 1954, pp. 50-51.

- 1 2 Shanta Rani Sharma 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Shanta Rani Sharma 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Puri 1957, p. 1-2.

- ↑ Puri 1957, p. 2.

- ↑ Puri 1957, pp. 4-6.

- ↑ Yadava 1982, p. 35.

- ↑ Singh 1964, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Puri 1966, p. 34-35.

- ↑ Mishra 1966, p. 18.

- ↑ Puri 1957, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Tripathi 1959, p. 226-227.

- ↑ Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India. Sterling Publishers. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004) [1986]. A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ↑ Dikshit, R. K. (1976). The Candellas of Jejākabhukti. Abhinav. p. 72. ISBN 9788170170464.

- ↑ Mitra, Sisirkumar (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9788120819979.

- ↑ Kala, Jayantika (1988). Epic scenes in Indian plastic art. Abhinav Publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-7017-228-4.

- 1 2 Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

Bibliography

- Ganguly, D. C. (1935). Narendra Nath Law, ed. "Origin of the Pratihara Dynasty". The Indian Historical Quarterly. Caxton. XI: 167–168.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1981). "The Gurjara-Pratiharas". In R. S. Sharma and K. K. Dasgupta. A Comprehensive history of India: A.D. 985-1206. 3 (Part 1). Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1.

- Mishra, V. B. (1954). "Who were the Gurjara-Pratīhāras?". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 35 (¼): 42–53. JSTOR 41784918.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1957). The history of the Gurjara-Pratihāras. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Sharma, Sanjay (2006). "Negotiating Identity and Status Legitimation and Patronage under the Gurjara-Pratīhāras of Kanauj". Studies in History. 22 (22): 181–220. doi:10.1177/025764300602200202.

- Sharma, Shanta Rani (2012). "Exploding the Myth of the Gūjara Identity of the Imperial Pratihāras". Indian Historical Review. 39 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1177/0376983612449525.

- Singh, R. B. (1964). History of the Chāhamānas. N. Kishore.

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1959). History of Kanauj: To the Moslem Conquest. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0478-4.

- Yadava, Ganga Prasad (1982). Dhanapāla and His Times: A Socio-cultural Study Based Upon His Works. Concept.