Hattiesburg, Mississippi

| Hattiesburg, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| |

| Nickname(s): The Hub City | |

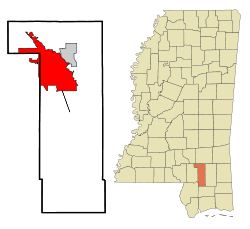

Location of Hattiesburg in the State of Mississippi | |

Hattiesburg, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 31°18′57″N 89°18′31″W / 31.31583°N 89.30861°WCoordinates: 31°18′57″N 89°18′31″W / 31.31583°N 89.30861°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| Counties | Forrest, Lamar |

| Founded | 1882 |

| Incorporated | 1884 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Johnny DuPree (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 54.3 sq mi (140.6 km2) |

| • Land | 53.4 sq mi (138.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.9 sq mi (2.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 171 ft (52 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 45,989 |

| • Estimate (2015) | 46,805 |

| • Density | 877/sq mi (338.5/km2) |

| • Metro | 148,839 |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 39401-39404, 39406, 39407 |

| Area code(s) | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-31020 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0691565 |

| Website |

www |

Hattiesburg is a city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, primarily in Forrest County (where it is the county seat[1]) and extending west into Lamar County. The city population was 45,989 at the 2010 census,[2] with an estimated population of 46,805 in 2015.[3] It is the principal city of the Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses Forrest, Lamar and Perry counties.

Founded in 1882 by civil engineer William H. Hardy, Hattiesburg was named in honor of Hardy's wife Hattie. The town was incorporated two years later with a population of 400. Hattiesburg's population first expanded as a center of the lumber and railroad industries, from which was derived the nickname "The Hub City". It now attracts newcomers to the area because of the diversity of the economy, strong neighborhoods and the central location in South Mississippi.

Hattiesburg is home to The University of Southern Mississippi (originally known as Mississippi Normal College) and William Carey University (formerly William Carey College). South of Hattiesburg is Camp Shelby, the largest National Guard training base east of the Mississippi River.

History

.jpg)

.jpg)

What is now Hattiesburg was previously inhabited by the Choctaw Native Americans. Between 1763 and 1783 the area that is currently Hattiesburg fell under the jurisdiction of the colony of British West Florida.[5] The area switched to being under the jurisdiction of the newly created United States of America after 1783 and was obtained by the United States from its Native American inhabitants under the terms of the Treaty of Mount Dexter in 1805. After the treaty was ratified, European-American settlers began to move into the area.

Hattiesburg is positioned at the fork of the Leaf and Bouie Rivers, and was founded in 1882 by Captain William H. Hardy, a civil engineer.

The city of Hattiesburg was incorporated in 1884 with a population of approximately 400. Originally called Twin Forks and later Gordonville, the city received its final name of Hattiesburg from Capt. Hardy, in honor of his wife Hattie.

Also in 1884, a railroad — known then as the New Orleans and Northeastern — was built from Meridian, Mississippi, through Hattiesburg to New Orleans. The completion of the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad (G&SIRR) from Gulfport, Mississippi, to Jackson, Mississippi, ran through Hattiesburg and ushered in the real lumber boom in 1897. Though it was 20 years in the building, the G&SIRR more than fulfilled its promise. It gave the state a deep water harbor, more than doubled the population of towns along its route, built the City of Gulfport and made Hattiesburg a railroad center. In 1924, the G&SIRR operated as a subsidiary of the Illinois Central Railroad but lost its independent identity in 1946.

Hattiesburg gained its nickname, the Hub City, in 1912 as a result of a contest in a local newspaper. This suggestion came because the city was the intersection of a number of important rail lines. Later the city also became the intersection of U.S. Highway 49, U.S. Highway 98 and U.S. Highway 11, and later, Interstate 59. Hattiesburg is centrally located less than 100 miles from the state capital of Jackson as well as the Mississippi Gulf Coast, New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama.[6]

The region around Hattiesburg was involved in the nuclear arms race of the Cold War. In the 1960s, two nuclear devices were detonated in the salt domes near Lumberton, Mississippi, about 28 miles southwest of Hattiesburg. Extensive follow-up of the area by the EPA has not revealed levels of nuclear contamination in the area that would be harmful to humans.

Throughout the 20th Century, Hattiesburg benefited from the founding of Camp Shelby (now a military mobilization center), two major hospitals, and two colleges, The University of Southern Mississippi and William Carey University. The growing metropolitan area that includes Hattiesburg, Forrest and Lamar Counties, was designated a Metropolitan Statistical Area in 1994 with a combined population of more than 100,000 residents.[7]

Despite being about 75 miles (121 km) inland, Hattiesburg was hit very hard in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina. Around 10,000 structures in the area received major damage of some type. Approximately 80 percent of the city's roads were blocked by trees and power was out in the area for up to 14 days. The storm killed 24 people in Hattiesburg and the surrounding areas. The city is strained by a large influx of temporary evacuees and new permanent residents from coastal Louisiana and Mississippi towns to the south, where damage from Katrina was catastrophic.

The City is also known for its police department, as it was the first — and for almost a decade the only — Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies federally accredited law enforcement agency in the State of Mississippi. The department is serviced by its own training academy, which has traditionally been one of the most difficult basic academies in the country with over a 50% attrition rate.

The Hattiesburg Zoo at Kamper Park is a longstanding tourist attraction in the city.[8]

In 2011, Hattiesburg Historic Neighborhood District was named one of the "Great Places In America," to live by the American Planning Association. Places are selected annually and represent the gold standard in terms of having a true sense of place, cultural and historical interest. The twenty-five-block neighborhood has one of the best collections of Victorian-era houses in Mississippi with more than ninety percent of the houses substantially renovated and maintained. The Hattiesburg Historic Neighborhood District [HHNA] was Hattiesburg’s first historic district added to National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The Historic Neighborhood District is also part of a Historic Conservation District and protected by Historic Hattiesburg Design Guidelines.[9]

In 2013, the Hattiesburg Historic Neighborhood District celebrated the 38th Annual Victorian Candlelit Christmas and Holiday Tour of Homes. During the two nights of the Victorian Candlelit Christmas, the sidewalks are glowing with thousands of candles in white bags lining the sidewalks. Christmas carolers from the three churches, Sacred Heart, Court Street Methodist and Bay Street Presbyterian, stroll house to house providing Christmas music while horse-drawn carriages slowly move through the neighborhood taking the visitors back in time. [10]

The Miss Hospitality Pageant began in 1949. Hattiesburg received sponsorship of the state pageant in December 1997. The purpose of the pageant is the identification and presentation of a young and knowledgeable lady to help promote the state in tourism and economic development. Contestants are judged on the following categories: panel interview, one-on-one interview competition, Mississippi speech competition, commercial/black dress competition, and evening gown competition. The 2011 winner was Ann Claire Reynolds who is a junior at University of Southern Mississippi majoring in elementary education and special education.

Hattiesburg is home to the African American Military History Museum. Opened in 1942 to serve African Americans serving at Camp Shelby and now on the National Register of Historic Places. The museum started out as a USO Club location and is the only remaining original club location left in the United States. USO's mission statement is to lift the spirits of America's troops and their families. Exhibits include: Revolutionary War, the Founding of Hattiesburg, Buffalo Soldiers, World Wars I and II, Desegregation, Korean War, Vietnam, Desert Storm, Global War on Terrorism, You Can Be A Soldier, Hattiesburg's Hall of Honor, and World Map. The museum is dedicated to the African American soldiers that have fought for their country from Buffalo Soldiers to Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Civil rights movement

Hattiesburg and the unincorporated African American community of Palmers Crossing played a key role in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s. In 1959, black Korean War veteran Clyde Kennard applied to attend then all-white Mississippi Southern College (today University of Southern Mississippi). He was denied admission on account of his race, and when he persisted, the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission conspired to have him framed for a crime, for which he was sentenced to seven years in Parchman Prison. For years, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People leaders Medgar Evers, Vernon Dahmer, and other Forrest County civil rights activists fought to overturn the conviction.[11]

Forrest County Registrar Theron Lynd prevented blacks from registering to vote. Thirty percent of the population was black, but less than 1% of them were on the voting rolls, while white registration was close to 100%. In 1961, the U.S. Justice Department filed suit against Lynd and he became the first southern registrar to be convicted under the Civil Rights Act of 1957 for systematically violating African American voting rights.[12]

In 1962, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began one of its first voter-registration projects in Hattiesburg under the auspices of Council of Federated Organizations. By 1964, the Delta Ministry was active in the city. In cooperation with the NAACP and local civil rights leaders, they formed the Forrest County Voters League.[13] In conjunction with the 1963 elections, civil rights leaders organized a statewide "Freedom Ballot", a mock election that demonstrated both the statewide pattern of voting rights discrimination and the strong desire of Mississippi blacks for full citizenship. Despite the serious risk of both physical and economic retaliation, almost half of Forrest County blacks participated, the highest turnout in the state.[14]

January 22, 1964, was "Freedom Day" in Hattiesburg, a major voter registration effort supported by student demonstrators and 50 northern clergymen. For the first time since Reconstruction, an inter-racial protest was allowed to picket the courthouse for voting rights without being arrested. Roughly 100 African Americans attempted to register, though only a few were allowed into the courthouse and fewer still were added to the rolls.[15] Each day thereafter for many months the courthouse protest was resumed in what became known as the "Perpetual Picket."[16]

During Freedom Summer in 1964, the Hattiesburg/Palmers Crossing project was the headquarters for all civil rights activity in the 5th Congressional District and the largest and most active site in the state with more than 90 volunteers and 3,000 local participants. Hundreds of Forrest County blacks tried to register to vote at the courthouse, but most were prevented from doing so. More than 650 children and adults attended one of the seven Freedom Schools in Hattiesburg and Palmers Crossing, three freedom libraries were set up with donated books, and a community center was established. Many whites opposed civil rights efforts by blacks, and both summer volunteers and local African Americans endured arrests, beatings, firings, and evictions.[17]

Forrest County was also a center of activity for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) which sent a slate of delegates to the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City to challenge the seating of the all-white, pro-segregation delegates elected by the regular party in primaries in which African Americans could not participate. Victoria Jackson Gray of Palmers Crossing ran on the MFDP ticket against incumbent Senator John Stennis and John Cameron of Hattiesburg ran for Representative in the 5th District. With blacks still denied the vote, they knew they could not be elected, but their candidacies and campaigns advanced the struggle for voting rights.[18]

On the night of January 10, 1966, the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan attacked the Hattiesburg home of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer with firebombs and gunfire. Dahmer was the most prominent black leader in the county and had been the primary civil rights leader for many years. Just prior to the attack, he had announced that he would help pay a $2 poll tax for black voters too poor to do so themselves. Dahmer held off the Klan with his rifle to give his wife, their three young children, and elderly aunt time to escape their burning home, but he died of burns and smoke inhalation the next day. His murder sparked large protest marches in Hattiesburg. A number of Klansmen were arrested for the crime and four were eventually convicted. After four previous trials had ended in deadlocks, KKK Imperial Wizard Samuel Bowers was finally convicted in August 1998 for ordering the assassination of Dahmer. He was sentenced to life in prison.[19][20]

In 1970, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against trespass convictions for civil rights protesters in Adickes v. S.H. Kress Co.. The case involved a sit-in at the lunch counter of the S. H. Kress & Co. downtown.

Vela Uniform/Project Dribble nuclear tests

Vela Uniform was an element of Project Vela conducted jointly by the United States Department of Energy and the Advanced Research Projects Agency. Its purpose was to develop seismic methods for detecting underground nuclear testing. The Project Dribble program involved two nuclear detonations. Test SALMON occurred on October 22, 1964, with a 5.3 kiloton yield; test STERLING was detonated December 3, 1966, with a yield of 380 tons.[21] Both detonations took place within Tatum Salt Dome, southwest of the Hattiesburg/Purvis area.

Geography

Most of Hattiesburg is in Forrest County. A smaller portion on the west side is in Lamar County with more of the abundant commercial land added in a 2008 annexation. This consists of first, a narrow stretch of land lying east of I-59, and second, an irregularly-shaped extension into West Hattiesburg. In the 2000 census, 42,475 of the city's 44,779 residents (94.9%) lived in Forrest County and 2,304 (5.1%) in Lamar County.[22]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 54.3 square miles (140.6 km2), of which 53.4 square miles (138.3 km2) is land and 0.89 square miles (2.3 km2), or 1.63%, is water.[2]

Hattiesburg is 74 miles (119 km) north of Biloxi and 90 miles (140 km) southeast of Jackson, the state capital.

Climate

Hattiesburg has a humid subtropical climate, with short, mild winters and hot, humid summers. Snowfall is extremely rare, but on December 11, 2008, areas around Hattiesburg received 3 to 5 inches (76 to 127 mm). As is the case throughout the southern United States, severe thunderstorms can pose a threat, particularly during spring. Such storms spawn frequent lightning, heavy rain, occasional large hail and tornadoes.[23][24] A recent tornado to affect the Hattiesburg area was the EF4 that struck on February 10, 2013, between roughly 5:00 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. CST. This tornado formed in Lamar County just west of Oak Grove and quickly increased in size and intensity. Although the most severe damage occurred in the Oak Grove area especially near Oak Grove High School, the tornado continued eastward into Hattiesburg causing widespread EF1-EF3 damage to the southern portion of the University of Southern Mississippi campus and the areas just north of downtown, before heading into neighboring Petal and rural Forrest County. No fatalities and over 80 injuries were reported, which was attributed to the nearly 30 minute tornado warning lead time.[25][26]

| Climate data for Hattiesburg, Mississippi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 87 (31) |

86 (30) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

106 (41) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

106 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 58.5 (14.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

69.9 (21.1) |

76.7 (24.8) |

83.5 (28.6) |

88.7 (31.5) |

90.8 (32.7) |

90.8 (32.7) |

86.9 (30.5) |

78.3 (25.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

60.6 (15.9) |

76.47 (24.71) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

40.7 (4.8) |

47.6 (8.7) |

54.5 (12.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

69.8 (21) |

72.4 (22.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

66.9 (19.4) |

55.6 (13.1) |

46.6 (8.1) |

39.6 (4.2) |

55.54 (13.07) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 4 (−16) |

−1 (−18) |

17 (−8) |

29 (−2) |

38 (3) |

49 (9) |

55 (13) |

55 (13) |

40 (4) |

23 (−5) |

18 (−8) |

4 (−16) |

−1 (−18) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.31 (160.3) |

5.81 (147.6) |

5.35 (135.9) |

4.95 (125.7) |

4.45 (113) |

4.84 (122.9) |

5.68 (144.3) |

5.71 (145) |

4.48 (113.8) |

3.61 (91.7) |

4.92 (125) |

5.48 (139.2) |

61.59 (1,564.4) |

| Source: [27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 1,172 | — | |

| 1900 | 4,175 | 256.2% | |

| 1910 | 11,733 | 181.0% | |

| 1920 | 13,270 | 13.1% | |

| 1930 | 18,601 | 40.2% | |

| 1940 | 21,026 | 13.0% | |

| 1950 | 29,474 | 40.2% | |

| 1960 | 34,989 | 18.7% | |

| 1970 | 39,648 | 13.3% | |

| 1980 | 40,829 | 3.0% | |

| 1990 | 41,882 | 2.6% | |

| 2000 | 44,779 | 6.9% | |

| 2010 | 45,989 | 2.7% | |

| Est. 2015 | 46,805 | [3] | 1.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 45,989 people residing in the city. 52.8% were African American, 40.5% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.1% from some other race and 1.1% from two or more races. 4.3% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census of 2000, there were 44,779 people, 17,295 households, and 9,391 families residing within the city limits. The population density was 909.0 people per square mile (351.0/km²). There were 19,258 housing units at an average density of 391.0 per square mile (150.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 49.95% White, 47.34% African American, 0.15% Native American, 1.22% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.52% from other races, and 0.80% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.41% of the population.

There were 17,295 households out of which 25.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.1% were married couples living together, 19.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.7% were non-families. 34.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city the population was spread out with 21.5% under the age of 18, 24.4% from 18 to 24, 26.3% from 25 to 44, 16.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females there were 85.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were approximately 81.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,409, and the median income for a family was $32,380. Males had a median income of $26,680 versus $19,333 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,102. About 21.5% of families and 28.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 36.3% of those under age 18 and 16.7% of those age 65 or over.

Religion

The Hattiesburg Metropolitan area has an Evangelical Protestant majority with 66,000 members. The Southern Baptist Convention has 85 congregations and 53,000 members. The United Methodist Church has 35 congregations and 9,000 members. The third largest is the Presbyterian Church in America with 5 congregations and 1,518 members.[29]

The Catholic Church has four parishes.

Economy

Hattiesburg is home to several national business branches that hold thousands of jobs across the Pine Belt. It was headquarters to the now defunct International Filing Company and currently hosts branches of Kohler Engines and BAE Systems Inc., as well as Berry Plastics and the Coca-Cola Bottling Co., Pepsi Cola Bottling Co., and Budweiser Distribution Co. Companies such as Sunbeam (shared with Mr. Coffee, and the Coleman Company) and Kimberly Clark used to manufacture in Hattiesburg.

The main shopping mall is Turtle Creek Mall.

Arts and culture

Theaters

- The Saenger Theatre was one of the seven built and operated by the Saenger brothers. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and hosts an annual Mississippi Miss Hospitality Competition, along with other productions.

- William Carey Center and Dinner Theater.[30][31]

- University of Southern Mississippi Theatre Department features original productions and National Theatre Live.[32]

Galleries

- A GALLERY, 134 E. Front Street.

- Hattiesburg Arts Council Gallery at the Hattiesburg Cultural Center, 723 Main Street.

- Lucile Parker Art Gallery. Located in the Thomas Fine Arts Building on William Carey University's Hattiesburg campus. The collection consists of 141 artworks by Lucile Parker, and 17 by Marie Hull. From August to May, the gallery features exhibitions of local, state, and nationally known artists.

- Sarah Gillespie Collection at William Carey University, 498 Tuscan Avenue. This is an extensive collection of twentieth century Mississippi art.

- University of Southern Mississippi Art Gallery.[30][31]

Museums

- African American Military History Museum, 305 E. 6th Street.

- Mississippi Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby.

- Freedom Summer Trails.

- Hattiesburg Area Historical Society Museum, 723 Main Street.

- De Grummond Children's Literature Museum.[30][31]

The Train Depot

The Hattiesburg Train Depot was constructed in 1910 by the Southern Railway Company, and was the city's largest and most architecturally significant depot. The City of Hattiesburg purchased the depot and 3.2 acres (1.3 ha) of land from Norfolk Southern Railway in 2000, and began a seven-year, $10 million restoration. The completed depot now functions as an intermodal transportation center for bus, taxi and rail, as well as a space for exhibitions, meetings and special events.[33]

Government

Hattiesburg is governed via a mayor-council system. The mayor, currently Johnny DuPree, is elected at large. The city council consists of five members who are elected from one of five wards. The current city council consists of the members Henry Naylor, Kim Bradley, Carter Carroll, Mary Dryden, and Deborah Delgado. [34] Sharon Waits currently holds the position of Chief Financial Officer for the city. [35] Lamar Rutland, a native of Hattiesburg and certified professional Civil Engineer, was appointed in 2014 as the city's Director of Engineering.[36] The current Director of Urban Development is Pattie Brantley. The department currently employs 24 citizens. [37]

Education

Public education in Hattiesburg is served by the Hattiesburg Municipal Separate School District, servicing grades K-12.

High schools

- Hattiesburg High School (Grades 9-12)

- Sacred Heart High School (Grades 7-12)

- Presbyterian Christian School (Grades 7-12)

- The Adept School

- North Forrest High School (Grades 7-12)

- Oak Grove High School (Grades 9-12)

(Oak Grove Schools are under the Lamar County School District)

Alternative schools

- Mary Bethune Attendance Center (Grades 7-11)

Middle schools

- N. R. Burger Middle School (Grades 7 & 8)

- Oak Grove Middle School (Grades 6-8)

Colleges

Hattiesburg is home to the main campuses of two institutions of higher learning: the public University of Southern Mississippi (USM) and the private Baptist-supported William Carey University. Both have campuses in other locations; USM has a campus in Long Beach, Mississippi, and William Carey has campuses in Gulfport, and New Orleans, Louisiana. The Forrest County Center of Pearl River Community College, a public institution, is located in Hattiesburg, with the main campus located in Poplarville, Mississippi. Antonelli College, a proprietary school, also has a campus in Hattiesburg, with the main campus located in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Private schools

.jpg)

- Sacred Heart Catholic School (Grades PreK - 12)

- Presbyterian Christian School (Grades PreK-12)

- School of Excellence (Grades K-6) (Now Early Learning Center, 6 weeks to Pre-K)

- Lamar Christian School (Grades K-4 to 12)

- Bass Christian Elementary (Grades K-8)

- Bass Memorial Academy (Grades 9-12)

- Central Baptist School (Grades K-12)

- Benedict Day School (Grades K-8)

- Tide School (The Institute for Diverse Education) (Grades 4-10)

Libraries

Forrest County Public Library serves the city.

Media

FM radio

- WUSM-FM 88.5 (Public Radio)

- WAII 89.3 American Family Radio (Christian Contemporary)

- WJMG 92.1 (Urban Contemporary)

- WGDQ 93.1 (Urban oldies)

- WKZW 94.3 (Hot Adult Contemporary)

- WBBN 95.9 (Country Music)

- WXHB 96.5 (Southern Gospel)

- WFMM 97.3 Supertalk Mississippi (Talk)

- WMXI 98.1 (News/Talk)

- WLAU 99.3 Supertalk Mississippi (News/Talk)

- WNSL 100.3 (Pop music)

- WJKX 102.5 (Old School R&B)

- WFFX 103.7 (Active rock)

- WXRR 104.5 (Classic rock)

- WQID-LP 105.3 (Christian Contemporary)

- WZLD 106.3 (Urban)

- WLVZ 107.1 (Contemporary Christian)

AM radio

- WHJA 890 (Blues)

- WHSY 950 (News/Talk)

- WFOR 1400 (Fox Sports Radio)

- WORV 1580 (Gospel Music)

Television

- WDAM Channel 7 (NBC) (ABC)

- WHLT Channel 22 (CBS)

- WHPM-LD Channel 23 (Fox)

Newspapers

- Hattiesburg American, Hattiesburg's daily newspaper.

- The Lamar Times, a weekly community newspaper serving the residents of West Hattiesburg and Lamar County.

- The Petal News, the weekly newspaper of Petal, MS.

- The Richton Dispatch, A weekly newspaper serving Perry County, MS.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Rail

Amtrak's Crescent train connects Hattiesburg with the cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Charlotte, Atlanta, Birmingham and New Orleans. The Amtrak station is located at 308 Newman Street.

Rail freight service is offered by three Class I railroads: CN to Jackson and Mobile, Kansas City Southern to Gulfport, and Norfolk Southern to Meridian and New Orleans.

Mass transit

Hattiesburg owns and operates the city's mass transit service, HCT, Hub City Transit. HCT offers daily routes to many major thoroughfares. The Intermodal Depot downtown services Amtrak as well as the city transit services. Due to recent growth in passenger transport in the city, HCT is currently planning additional routes and services, including bus service to the suburbs of Oak Grove and Petal.

Air

Hattiesburg-Laurel Regional Airport is located in an unincorporated area in Jones County, near Moselle.[38] It offers daily flights between Hattiesburg and Atlanta, Georgia via Silver Airways. PIB airport also has an 18-hole golf course and business park located on the premises.

The city of Hattiesburg maintains the Hattiesburg Bobby L. Chain Municipal Airport (HBG) in the Hattiesburg/Forrest County Industrial Park. Located four miles south of the city center, the municipal airport provides business and general aviation services for much of South Mississippi.

Highways

| Interstate 59, runs north to Meridian, Mississippi, and south to New Orleans. |

| U.S. Highway 11 runs parallel to Interstate 59. |

| U.S. Highway 49 runs north to Jackson, Mississippi, and south to Gulfport, Mississippi. |

| U.S. Highway 98 runs west to Columbia, Mississippi, and southeast to Mobile, Alabama. |

| Mississippi Highway 42 |

| Mississippi Highway 589 |

| Mississippi Highway 198 |

| Mississippi Highway 24 |

Major roads

Major east-west roads include: 4th Street, Hardy Street (aka Highway 98 after passing Interstate 59), Lincoln Road, Classic Drive, 7th Street, and State Highway 42.

Major north-south roads include: Interstate 59, Highway 11/Broadway Drive, West Pine Street, Main Street, Highway 98, 28th Avenue, Golden Eagle Avenue, 38th Avenue, and 40th Street.

Notable people

- Victoria Jackson Gray Adams, educator and civil rights leader

- Fred Armisen, actor, comedian and musician

- Steven Barthelme, writer and critic

- Wally Berg, first American mountaineer to summit Lhotse, in 1990

- Roger Brent, biologist

- Jesse L. Brown, first African-American naval aviator in the United States Navy

- Jimmy Buffett, musician

- Shelby Cannon, tennis player

- Paul Ott Carruth, former NFL player

- Robert Carson, left-handed pitcher for the New York Mets

- Lewis Elliott Chaze, journalist and author of 10 novels

- Shea Curry, actress

- Vernon Dahmer, civil rights leader killed in Hattiesburg by Klansmen in 1966

- Tyler Dickerson, singer

- Bob Dudley, BP executive in charge of Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Wesley Eure, actor in Days of Our Lives and Land of the Lost

- Woody Evans, writer and librarian

- Brett Favre, former National Football League quarterback, three-time NFL MVP, Super Bowl XXXI champion

- Tim Floyd, former head coach of the University of Texas at El Paso men's basketball team

- Afroman, musician (born as well as raised in Palmdale but also raised in Hattiesburg)

- Joey Gathright, MLB outfielder

- Todd Grisham, ESPN Sportscenter anchor, Former WWE announcer.

- Gary Grubbs, Hollywood and television actor

- Ray Guy, former punter for the Oakland Raiders

- Charlie Hayes, former professional baseball player

- Beth Henley, Pulitzer Prize–winning writer

- Eddie Hodges, actor and singer

- Clifton Hyde, musician and member of the Blue Man Group

- Harold Jackson, former NFL wide receiver

- Fred Lewis, outfielder for the Hiroshima Toyo Carp

- Louis Lipps, former NFL Pro-Bowl wide receiver and 1984 AFC Rookie of the Year, Pittsburgh Steelers

- Jack Lucas, the youngest Marine ever to receive the Medal of Honor

- Mark Mann, artist

- Danny Manning, former professional basketball player

- Walter E. Massey, former president of Morehouse College and director of the National Science Foundation under George Bush. Currently President of Art Institute of Chicago - 2010-Present (2015)

- Oseola McCarty, famous benefactor and winner of the Presidential Citizens Medal

- Matt Miller, professional baseball player

- Picasso Nelson, American football player

- Jonathan Papelbon, pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies

- Van Dyke Parks, musician

- Todd Pinkston, former NFL Player for Philadelphia Eagles

- Stephen Purdy, Broadway musician and vocal teacher

- Johnny Rawls, soul blues singer and guitarist

- Purvis Short, former NBA professional basketball player

- Taylor Spreitler, Actress

- Robert L. Stewart, NASA astronaut

- Walter Suggs, former professional football player Houston Oilers

- James Wheaton, actor, director and educator (resident from infancy to age 12)

- Webb Wilder, musician and actor

- Amos Wilson, author, activist

- Craig Wiseman, songwriter

- Walter H. Yates, Jr., major general, U.S. Army

- Walter Young, former professional baseball player

See also

References

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Hattiesburg city, Mississippi". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- 1 2 "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ Grimsley, Reagan L. (2004). Hattiesburg in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia. p. 62.

- ↑ Governor Johnstone and trade in British West Florida, 1764-1767 (Wichita State University, 1968)

- ↑ Reagan L. Grimsley, Hattiesburg In Vintage Postcards, (SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.)

- ↑ Reagan L. Grimsley, Hattiesburg in Vintage Postcards, Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

- ↑ Vernon N. Kisling, Jr., ed. (2001). "Zoological Gardens of the United States (chronological list)". Zoo and Aquarium History. USA: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-3924-5.

- ↑

- ↑ "Annual Victorian Candlelit Christmas". Hattiesburghistoricneighborhood.com. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement - History & Timeline, 1959". Crmvet.org. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "United States of America vs. Theron C. Lynd". University of Southern Mississippi. Archived from the original on 9 November 2004.

- ↑ "Historic Sites of the Civil Rights Movement in Hattiesburg". University of Southern Mississippi. Archived from the original on 22 January 2001.

- ↑ "Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement - History & Timeline, 1963 (July-December)". Crmvet.org. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement - History & Timeline, 1964 (Jan-June)". Crmvet.org. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ Branch, Taylor (1998). Pillar of Fire. Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Randall, Herbert (2001). Faces of Freedom Summer. University of Alabama Press.

- ↑ Carson, Clayborne (1981). In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Davis, Townsend (1998). Weary Feet, Rested Souls. W.W. Norton.

- ↑ Biography of Sam Bowers. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved on April 24, 2008.

- ↑ "United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992" (PDF). US Department of Energy Nevada Operations Office. December 2000. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ↑ "Subcounty population estimates: Mississippi 2010-2012" (CSV). United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2014-01-30. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ "More snow by noon". Hattiesburg American. 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ "More snow by noon". Hattiesburg American. 2008-12-11.

- ↑ "Pine Belt Tornado Event". National Weather Service Jackson, MS. NOAA/NWS. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ "Tornado hits Hattiesburg, Miss.". USAToday. Gannett. February 10, 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". NOAA. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ↑ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | Maps & Reports". Thearda.com. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- 1 2 3 "Museums". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Arts". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Department of Theatre | The University of Southern Mississippi". Usm.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Train Depot". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ "City Council". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Chief Financial Officer". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Engineering Department". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Urban Development". City of Hattiesburg. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Contact - Hattiesburg-Laurel Airport". Flypib.com. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hattiesburg, Mississippi. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hattiesburg. |

- City of Hattiesburg official website

- Hattiesburg American

- Hattiesburg Area Historical Society

- Hattiesburg Visitor Information

- Hattiesburg.com - visitor and business information

- History of Hattiesburg's Jewish community (from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life)

- The University of Southern Mississippi McCain Library and Archives--Blind Roosevelt Graves and His Brother

- Hattiesburg-Bobby L. Chain Municipal Airport (HBG)

- Great Places In America

.svg.png)