Oxnard, California

| Oxnard, California | ||

|---|---|---|

| General law city[1] | ||

| City of Oxnard | ||

|

Oxnard gateway monument sign. | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Gateway to the Channel Islands | ||

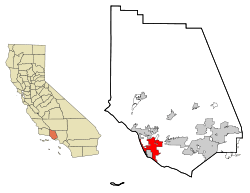

Location in Ventura County and the state of California | ||

Oxnard Location in the United States | ||

| Coordinates: 34°11′29″N 119°10′57″W / 34.19139°N 119.18250°WCoordinates: 34°11′29″N 119°10′57″W / 34.19139°N 119.18250°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | California | |

| County | Ventura | |

| Incorporated | June 30, 1903[2] | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Council–manager | |

| • City council[3] |

Mayor Tim Flynn Bryan A. MacDonald Carmen Ramírez Dorina Padilla Bert Perello | |

| • City treasurer | Danielle Navas | |

| • City clerk | Daniel Martinez[4] | |

| • City manager | Greg Nyhoff[5] | |

| Area[6] | ||

| • Total | 39.208 sq mi (101.548 km2) | |

| • Land | 26.894 sq mi (69.656 km2) | |

| • Water | 12.314 sq mi (31.893 km2) 31.41% | |

| Elevation[7] | 52 ft (16 m) | |

| Population (April 1, 2010)[8] | ||

| • Total | 207,254 | |

| • Rank |

1st in Ventura County 19th in California | |

| • Density | 7,358/sq mi (2,841/km2) | |

| • Metro density | 7,360/sq mi (2,841/km2) | |

| Time zone | Pacific (UTC−8) | |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC−7) | |

| ZIP codes[9] | 93030–93036 | |

| Area code | 805 | |

| FIPS code | 06-54652 | |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652766, 2411347 | |

| Website |

www | |

Oxnard /ˈɒksnɑːrd/ is a city in the United States, located along the coast of Southern California. It is the 19th most populous city in California and the most populous in Ventura County. The city lies approximately 30 miles west of the Los Angeles city limits, and is part of the larger Greater Los Angeles area. The population of Oxnard is 203,585 as of the 2012 Financial Report.[10] Oxnard is the most populous city in the Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is listed as one of the wealthiest areas in America, with its residents making well above the average national income.[11][12]

Oxnard was incorporated in 1903. It is located at the western edge of the fertile Oxnard Plain, sitting adjacent to an agricultural center of strawberries and lima beans. Oxnard is also a major transportation hub in Southern California, with Amtrak, Union Pacific, Metrolink, Greyhound, and Intercalifornia stopping in Oxnard. Oxnard also has a small regional airport called Oxnard Airport (OXR). Oxnard is also the location of the National Weather Service forecast office that serves the Los Angeles area.[13]

History

Before the arrival of Europeans, the area that is now Oxnard was inhabited by Chumash Native Americans. The first European to encounter the area was Portuguese explorer João Rodrigues Cabrilho, who claimed it for Spain in 1542. During the mission period, it was serviced by the Mission San Buenaventura, established in 1782.

Ranching began to take hold among Californio settlers, who lost their regional influence when California became a US state in 1850. At about the same time, the area was settled by American farmers, who cultivated barley and lima beans.

Henry T. Oxnard, founder of today's Moorhead, Minnesota-based American Crystal Sugar Company who operated a successful sugar beet factory with his three brothers (Benjamin, James, and Robert) in Chino, California, was enticed to build a $2 million factory on the plain inland from Port Hueneme. Shortly after the 1897 beet campaign, a new town emerged, now commemorated on the National Register of Historic Places as the Henry T. Oxnard Historic District. Oxnard intended to name the settlement after the Greek word for "sugar", zachari, but frustrated by bureaucracy, named it after himself. Given the growth of the town of Oxnard, in the spring of 1898, a railroad station was built to service the plant, which attracted a population of Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican laborers and enough commerce to merit the designation of a town. Ironically, the Oxnard brothers never lived in their namesake city, and they sold both the Chino and the giant red-brick Oxnard factory with its landmark twin smokestacks in 1899 for nearly $4 million. The Oxnard factory operated from August 19, 1899 until October 26, 1959. Factory operations were interrupted in the Oxnard Strike of 1903.

Oxnard was incorporated as a California city on June 30, 1903, and the public library was opened in 1907. Prior to and during World War II, the naval bases of Point Mugu and Port Hueneme were established in the area to take advantage of the only major navigable port on California's coast between the Port of Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay, and the bases in turn encouraged the development of the defense-based aerospace and communications industries.

In the mid-20th century Oxnard grew and developed the areas outside the downtown with homes, industry, retail, and a new harbor named Channel Islands Harbor. Martin V. ("Bud") Smith (1916–2001) became the most influential developer in the history of Oxnard during this time. Smith's first enterprise in 1941 was the Colonial House Restaurant (demolished 1988) and then the Wagon Wheel Junction in 1947, (demolished 2011).[14] He was also involved in the development of the high-rise towers at the Topa Financial Plaza, the Channel Islands Harbor, Casa Sirena Resort, the Esplanade Shopping Mall, Fisherman's Wharf, the Carriage Square Shopping Center, the Maritime Museum, and many other major hotel, restaurant and retail projects.[15][16]

In June 2004, the Oxnard Police Department and the Ventura County Sheriff imposed a gang injunction over a 6.6-square-mile (17 km2) area of the central district of the city, in order to restrict gang activity.[17] The injunction was upheld in the Ventura County Superior Court and made a permanent law in 2005.[18] A similar injunction was imposed in September, 2006 over a 4.26-square-mile (11.0 km2) area of the south side of the city.[19]

Geography

Oxnard is located on the Oxnard Plain, an area with fertile soil. With its beaches, dunes, wetlands, creeks and the Santa Clara River, the area contains a number of important biological communities. Native plant communities include: coastal sage scrub, California Annual Grassland, and Coastal Dune Scrub species; however, most native plants have been eliminated from within the city limits to make way for agriculture and urban and industrial development. Also native to the region is the endangered Ventura Marsh Milkvetch, and the last self-sustaining population is in Oxnard in the center of a recently approved high-end housing development.[20]

Beaches

The city of Oxnard is home to over 20 miles (32 km) of scenic, relatively uncrowded coastline. The beaches in Oxnard are large and the sand is exceptionally soft. The sand dunes in Oxnard, which were once much more extensive, have been used to recreate Middle-Eastern desert dunes in many movies, the first being The Sheik with Rudolph Valentino. There are very few rocks or driftwood piles at most beaches, but Oxnard is known to have dangerous rip-currents at certain beaches.[21][22][23] Oxnard has good surfing at many of its beaches.

Beaches in Oxnard include: Ormond Beach, Silver Strand Beach, Hollywood Beach, Hollywood-By-the-Sea, Mandalay Beach, Oxnard Beach Park, Oxnard Shores, 5th Street Beach, Mandalay State Beach, McGrath State Beach and Rivermouth Beach.

Rivers

The Santa Clara River separates Oxnard and Ventura. Tributaries to this river include Sespe Creek, Piru Creek, and Castaic Creek.

Geology

Oxnard is on a tectonically active plate, since most of Coastal California is near the boundaries between the Pacific and North American Plates. The San Andreas Fault, which demarcates this boundary, is about 40 miles away.

One active fault line that transverses Oxnard is the Oak Ridge Fault, which straddles the Santa Clara River Valley westward from the Santa Susana Mountains, crosses the Oxnard Plain through Oxnard, and extends into the Santa Barbara Channel.

The fault has proven to be a significant contributor to seismic activity in the Oxnard region and beyond. The January 17, 1994 Northridge earthquake released a devastating magnitude 6.7 temblor, it is believed to have occurred in the Santa Clarita extension of the Oak Ridge Fault. Landslides and ridge-top shattering resulting from the Northridge earthquake were observed above Moorpark, a city 19.6 mi (31.5 km)[24] east of Oxnard.[25]

Minor earthquakes are frequent in the Oxnard area. For example, an earthquake with a preliminary magnitude of 3.2 struck at 9:53 pm centered at four miles (6 km) east-southeast of the city of Oxnard on October 16, 2009.[26][27] Another earthquake of magnitude 2.7 struck around 8:05 pm on December 1, 2014.[28] Another earthquake of magnitude 3.5 struck around 4:44 am on April 6, 2016.[29]

Climate

The city is situated in a Mediterranean (dry subtropical) climate zone, experiencing mild and relatively wet winters, and warm, dry summers, in a climate called the warm-summer Mediterranean climate. Onshore breezes keep the communities of Oxnard cooler in summer and warmer in winter than those further inland. The average mean temperature is 61 °F (16 °C). The average minimum temperature is 52 °F (11 °C) and the average maximum temperature is 69 °F (21 °C). Generally the weather is cool and dry, with 354 days of sunshine annually. The average annual precipitation is 15.62 in (397 mm).[30]

| Climate data for Oxnard (Camarillo Airport), California 1981–2010, extremes 1952–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 94 (34) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

101 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 65.5 (18.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

65.8 (18.8) |

68.8 (20.4) |

71.1 (21.7) |

72.5 (22.5) |

75.9 (24.4) |

76.8 (24.9) |

76.6 (24.8) |

73.5 (23.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

65.5 (18.6) |

70.63 (21.47) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

46.6 (8.1) |

47.9 (8.8) |

51.7 (10.9) |

56.2 (13.4) |

58.0 (14.4) |

58.5 (14.7) |

57.0 (13.9) |

52.7 (11.5) |

46.7 (8.2) |

42.1 (5.6) |

50.23 (10.12) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

30 (−1) |

33 (1) |

36 (2) |

42 (6) |

46 (8) |

49 (9) |

43 (6) |

35 (2) |

31 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

25 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.47 (88.1) |

3.71 (94.2) |

2.65 (67.3) |

0.79 (20.1) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.02 (0.5) |

0.04 (1) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.63 (16) |

1.31 (33.3) |

2.06 (52.3) |

15.22 (386.6) |

| Source: NOAA[31][32] | |||||||||||||

Wildlife and ecology

The area contains a number of important biological communities. Native plant communities include coastal sage scrub, California Annual Grassland, and Coastal Dune Scrub species; however, most native plants have been eliminated from within the city limits to make way for development. Also native to the region is the endangered Ventura Marsh Milkvetch, with the last self-sustaining population in Oxnard being at the center of a recently approved high-end housing development.[20]

Raccoons, skunks, possums, foxes, coyotes, and stray dogs and cats frequently roam neighborhoods.[33] The balance of wildlife in Oxnard is similar to that of most places in southern California, with small mammals being common in urbanized areas, like squirrels, raccoons, and skunks. Coyotes prey on these smaller mammals. Small birds and mammals can be food for stray, feral, and pet dogs and cats.[34]

Environment

Oxnard has more coastal power plants than any other city in California, with three fossil-fuel power plants providing energy for cities in both Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties.[35][36] The California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA) has identified Oxnard as a city excessively loaded by multiple sources of pollution.[37] The Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has categorized much of Oxnard in the top 10 percent of zip codes most negatively impacted by pollution in the state.[37] [38] In May 2015, the Oxnard City Council unanimously voted to extend the city moratorium on power plant construction. This moratorium extension occurred due to NRG/Southern California Edison's proposal, also referred to as the Puente Power Project,[37] to construct a new fossil-fuel power plant. The next morning, a NRG representative stated their case to replace the old power generation plant at Mandalay beach with a new, hi-tech, much cleaner and more efficient plant.[39]

Pesticides are used in the agricultural fields surrounding Oxnard, as the area is one of the nation's leading strawberry producers, with agriculture being one of the top contributors to Oxnard's economy. Strawberries depend on large applications of fumigants containing pesticides. The Center for Health Journalism reported four ZIP codes with the highest pesticide use in the state clustered around Oxnard.[40]

Rio Mesa High School, surrounded by agricultural fields of the Oxnard Plain, has been at the center of a Title VI Civil Rights Act complaint since 1999, covering three generations.[40] Title VI prohibits recipients of federal funding from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) routinely awards California pesticide regulators millions of dollars in grants. The EPA is required to ensure the recipients of its funding to be in compliance with Title VI.[41] The plaintiffs argue that California pesticide regulators violated Title VI, by approving permits for toxins that disproportionately impacted Latino schoolchildren, who attended schools adjacent to fields with the highest methyl bromide levels in the state.[42]

Architecture

The historical architectural styles of Oxnard ranch family homes are Victorian era, Italian style, and Carpenter Gothic.[43] In the Henry T. Oxnard Historic District, there are five Prairie School and eight Tudor Revival homes.[44] The district includes Mission/Spanish Revival, Bungalow/craftsman, Colonial Revival, and other architecture.[45]

Cityscape

Oxnard is a combination of neighborhoods, and urban development focused on the downtown, coastline, and harbor areas.[46] The city's main land uses are industrial, residential, commercial, and open space.[47] The city is characterized by one and two-story buildings, the only exception being several high rises in the northern part of the city. The city is surrounded by agricultural land and the Pacific Ocean, as well as the Santa Clara River. The city's primary development lies along Highway 101 and the other main roads.[48]

The Henry T. Oxnard Historic District is a 70-acre (28 ha) historic district that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in Oxnard. Covering approximately F and G Sts., between Palm and 5th Sts., in the city, the district includes 139 contributing buildings and includes homes mostly built before 1925.[45] It contains Craftsman and Revival architecture in abundance.[44][49]

Ormond Beach is a beach along the Oxnard coast. The beach, which stretches for two miles,[50] adjoins the Ormond Wetlands, some farmland, and power plant remains. It covers the area in between Points Hueneme and Mugu, and is a well-known birding area. The beach historically contained marshes, salt flat, sloughs, and lagoons, but surrounding agriculture and industry have drained, filled, and degraded the beach and wetlands. However, there is still a dune-transition zone-marsh system along much of the beach.[51][52]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 2,555 | — | |

| 1920 | 4,417 | 72.9% | |

| 1930 | 6,285 | 42.3% | |

| 1940 | 8,519 | 35.5% | |

| 1950 | 21,567 | 153.2% | |

| 1960 | 40,265 | 86.7% | |

| 1970 | 71,225 | 76.9% | |

| 1980 | 108,195 | 51.9% | |

| 1990 | 142,216 | 31.4% | |

| 2000 | 170,358 | 19.8% | |

| 2010 | 197,899 | 16.2% | |

| Est. 2015 | 207,254 | [53] | 4.7% |

2010

The 2010 United States Census[55] reported that Oxnard had a population of 197,899. The population density was 7358 people per square mile (2,841/km²). The racial makeup of Oxnard included 95,346 (48.2%) White, 5,771 (2.9%) African American, 2,953 (1.5%) Native American, 14,550 (7.4%) Asian, 658 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 69,527 (35.1%) from other races, and 9,094 (4.6%) from two or more races. In addition, 145,551 people (73.5%) were Hispanic or Latino, of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 14.9% of the population in 2010,[56] compared to 42.6% in 1980.[57]

The Census reported that 196,465 people (99.3% of the population) lived in households, 932 (0.5%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 502 (0.3%) were institutionalized.

There were 49,797 households, out of which 25,794 (51.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 28,319 (56.9%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 7,634 (15.3%) had a female householder with no husband present, 4,043 (8.1%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 3,316 (6.7%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 395 (0.8%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 7,090 households (14.2%) were made up of individuals and 2,665 (5.4%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.95. There were 39,996 families (80.3% of all households); the average family size was 4.20.

The population was spread out with 59,018 people (29.8%) under the age of 18, 23,913 people (12.1%) aged 18 to 24, 57,966 people (29.3%) aged 25 to 44, 40,584 people (20.5%) aged 45 to 64, and 16,418 people (8.3%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.9 years. For every 100 females there were 103.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.4 males.

There were 52,772 housing units at an average density of 1,962 per square mile (757.6/km²), of which 27,760 (55.7%) were owner-occupied, and 22,037 (44.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.8%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.7%. 107,482 people (54.3% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 88,983 people (45.0%) lived in rental housing units.

2000 census

As of the census[58] of 2000, there were 170,358 people, 43,576 households, and 34,947 families residing in the city. The population density was 6,729.7 inhabitants per square mile (2,598.8/km²). There were 45,166 housing units at an average density of 1,784.2 per square mile (689.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 42.1% White, 3.8% African American, 1.3% Native American, 7.4% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 40.4% from other races, and 4.7% from two or more races. Two-thirds of the population (66.2%) was Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 43,576 households out of which 46.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.4% were married couples living together, 14.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 19.8% were non-families. 14.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.85 and the average family size was 4.16

In the city the population was spread out with 31.8% under the age of 18, 11.8% from 18 to 24, 31.0% from 25 to 44, 17.3% from 45 to 64, and 8.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 104.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $48,603, and the median income for a family was $49,150. Males had a median income of $30,643 versus $25,381 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,288. About 11.4% of families and 15.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.4% of those under age 18 and 8.8% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

The economy of Oxnard is driven by defense, international trade, agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism. Oxnard is one of the key manufacturing centers in the Greater Los Angeles Area. The Port of Hueneme is the busiest and only deep-harbor commercial port between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and is vital to trade with the Pacific Rim economies. Companies utilizing the Port include Del Monte Foods, Chiquita, BMW, Land Rover, and Jaguar. Other key industries driving Oxnard's existence include finance, transportation, the high tech industry, and energy, particularly petroleum. Two large active oil fields underlie the city and adjacent areas: the Oxnard Oil Field, east of the city along 5th Street, and the West Montalvo Oil Field along the coast to the west of town. Tenby Inc.'s Oxnard Refinery, on 5th Street east of Del Norte Avenue, processes oil from both fields.

According to the city's 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[59] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | St. John's Regional Medical Center | 1,994 |

| 2 | Oxnard Union High School District | 1,500 |

| 3 | Waterway Plastics | 1,300 |

| 4 | City of Oxnard | 1,167 |

| 5 | Haas Automation | 996 |

| 6 | Aluminum Precision Products | 700 |

Other major employers include Naval Base Ventura County, Boskovich Farms, PTI Technologies, Procter & Gamble, Seminis, Spatz Laboratories, and Gills Onions.[60]

Some of the major companies headquartered in Oxnard are Haas Automation, Seminis, Raypak, Drum Workshop, Borla Performance,[61] Boss Audio and Robbins Auto Tops[62] Procter & Gamble and Sysco maintain their West Coast operations in Oxnard.

Agriculture

According to the Camarillo General Plan:[63] "The areas studied showed a high percentage of Group I soils, primarily located on the relatively flat Oxnard Plain. The Oxnard Plain, because of these high-quality agricultural soils, coupled with a favorable climate, is considered one of the most fertile areas in the world."

Oxnard has been known for several different crops over the years, including cucumbers, sugar beets, lima beans, Stock (the cut flower), and strawberries. In the years of Oxnard's growth during the 1970s and 80s, many farms and ranches were annexed for development, and many new development plans threatened much of the plain's farmland. In 1995, a grassroots effort known as SOAR (Save Open Space and Agricultural Resources) was initiated by farmers, ranchers and citizens of Ventura County in an effort to save the vast agricultural asset of the Oxnard Plain.

Oxnard strawberries

The Oxnard Plain is well known for its strawberries. According to the USDA, Oxnard is California's largest strawberry producer, supplying about one-third of the State's annual strawberry volume.[64] From the end of September through the end of October, strawberries are planted and harvesting occurs from mid-December through mid-July in Oxnard. The peak harvesting season in California runs from April through June, when up to 10 million pint baskets of strawberries are shipped daily.[65] The state of California supplies over 85 percent of U.S. strawberries, with the U.S. supplying for a quarter of total world production of strawberries.

Each year Oxnard hosts the California Strawberry Festival[66] during the summer at College Park next to Oxnard College, featuring vendors as well as food items based on the fruit such as strawberry nachos, strawberry pizza, strawberry funnel cake, strawberry sundaes, and strawberry champagne.[67][68]

Arts and culture

Oxnard cultural institutions include the Carnegie Art Museum, founded in 1907 as the Oxnard Public Library by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie; the Chandler Vintage Museum of Transportation and Wildlife, founded by the late Los Angeles Times publisher Otis Chandler, the Murphy Auto Museum,[69] the Channel Islands Maritime Museum,[70] and the Seabee Museum. The Henry T. Oxnard Historic District[71] is adjacent to the commercial downtown area where Heritage Square, a collection of restored Victorian and Craftsman houses that were once owned by Oxnard's pioneer families, is located.[72][73] Heritage Square is home to the Petit Playhouse[74] and the Elite Theatre Company.[75] The Oxnard Performing Arts and Convention Center[76] is home to the New West Symphony.[77] Oxnard also has the Oxnard Independent Film Festival[78] and the annual Channel Islands Tall Ships Festival.[79] The Herzog Winery is based in Oxnard[80] along with other wine tasting rooms.[81]

Music

Hip Hop producers Madlib, Kan Kick, rappers Spinz, Dudley Perkins, Anderson .Paak and bands in the punk "Nardcore" music scene are from Oxnard, including Dr. Know, Agression, Scared Straight, Ill Repute, False Confession, Stalag 13, Ten Foot Pole, No Motiv, and Habeas Corpus. The city and neighboring Ventura both maintain a thriving punk music scene to this day, driven by a fusion of both the skater and surfer cultures. Metal bands are also prominent in the region. Oxnard is also home to the annual Oxnard Salsa Festival, which takes place on the last week-end each July. For two days Oxnard hosts both local and international salsa bands in Plaza Park. Also Oxnard is home to the Japanese- American ska band kemuri.

Sports

The Dallas Cowboys held their pre-season training camp at River Ridge Field in Oxnard in 2001, 2004–06, 2008–10 and 2012-16 (the Cowboys trained at California Lutheran University in nearby Thousand Oaks in 1963–89). The New Orleans Saints trained in Oxnard in 2011.[82] The Los Angeles Raiders trained at River Ridge in the 1980s and 90s.[83]

On February 4, 2016, the Los Angeles Rams (an NFL team) selected Oxnard to be the site of their Official Team Activities and mini camp. On February 19, 2016, the city of Oxnard and the Rams reached a tentative agreement to host official team activities or OTAs and minicamp at River Ridge Playing Fields and on February 23, 2016, the Oxnard City Council voted unanimously 5-0 to allow the Los Angeles Rams to use the River Ridge Playing Fields facility from April 18 to June 17 and the locker room space from March 28 until June 24.

Education

The city of Oxnard is served by 54 public school campuses which provide education to more than 53,000 students in grades K–12. If all Oxnard public school districts were unified into one district, similar to cities such as New York and Los Angeles, it would be the 71st largest school district in the United States.[84]

Elementary and junior high schools

The city of Oxnard and surrounding communities are served by four different school districts which oversee education for students grades K–8. They are:

- Hueneme School District: Serves 7,600 students at 11 campuses in South Oxnard, Port Hueneme and Oxnard beach neighborhoods.

- Oxnard School District:[85] Serves 18,000 students at 21 campuses throughout Oxnard.

- Ocean View Elementary School District:[86] Serves 3,000 students at 6 campuses in South Oxnard.

- Rio School District:[87] Serves 5,000 students at 8 campuses in North Oxnard and El Rio.

On February 12, 2008, a shooting involving students occurred at E.O. Green Junior High School in Oxnard. Larry King was shot in one of the classrooms where he was later taken to St Johns Hospital and died.[88]

There are a number of private K–8 schools including the non-denominational Mary Law Private School and several Catholic schools, which are administered by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

High schools

All public high schools in Oxnard are operated by the Oxnard Union High School District, which provides high school education to 20,000 students at 10 campuses in three cities (Oxnard, Camarillo and Port Hueneme) as well as the unincorporated areas of El Rio, Somis and Channel Islands.

OUHSD oversees Adolfo Camarillo High School, Channel Islands High School, Hueneme High School, Oxnard High School, Pacifica High School and Rio Mesa High School, as well as the continuation high schools Frontier, Oxnard Adult, Pacific View and Puente. Santa Clara High School is a private Catholic high school.

Colleges and universities

Oxnard is served on the collegiate level by Oxnard College and nearby California State University Channel Islands. Additionally, California Lutheran University, California State University, Northridge, ITT, University of Phoenix, University of California, Santa Barbara, National University and Azusa Pacific University have satellite campuses in Oxnard.

Transportation

Road

The Ventura Freeway (US 101) is the major highway running through Oxnard, connecting Ventura and Santa Barbara to the northwest, and Los Angeles to the southeast. The Pacific Coast Highway (State Route 1) heads down the coast south to Malibu. Highway 232 (Vineyard Avenue), heads northeast, providing connections to California State Route 118 to Saticoy and the junction with California State Route 126 which goes to Santa Paula, Fillmore and the Santa Clarita.

Port

The Port of Hueneme is located south of Oxnard in the city of Port Hueneme and is jointly operated by the United States Navy and the Oxnard Harbor District. The port is the only deep water port between the Port of Long Beach and the Port of San Francisco as well as the only military deep water port between San Diego Bay and Puget Sound.

The Port of Hueneme is a shipping and receiving point for a wide variety of resources with destinations in the larger population centers of the Los Angeles Basin. Resources include automobiles, pineapples, and bananas. Agricultural products such as onions, strawberries, and flowers are shipped.[89]

The United States Navy maintains a facility at Port Hueneme, in support of the naval air station at Point Mugu to the south, with which it comprises Naval Base Ventura County. Port Hueneme is the West Coast home of the Naval Construction Force, the "Seabees", as well as a link in the coastal radar system.

Harbor

Oxnard is home to one harbor: Channel Islands Harbor, with Ventura Harbor located seven miles (11 km) north in adjacent Ventura. Channel Islands Harbor is located on the south shore of Oxnard and is nicknamed the "Gateway to the Channel Islands" because of the high number of operations that sail to the islands out of the harbor. Both harbors are vital fishing industry harbors.

Airport

Oxnard Airport is a general aviation airport within the city that is owned and operated by the County of Ventura.

Public transit

The Oxnard Transit Center serves as a major transit hub for the city, as well as the west county.

Rail

- Metrolink

- 6 round trip trains from Ventura County Line provide commuter service to Los Angeles on the weekdays during peak hours.

- Amtrak

- 10 round trip Pacific Surfliners daily through Los Angeles to San Diego. Some northbound trains to Santa Barbara continue on to San Luis Obispo. The Coast Starlight, that travels from Los Angeles to Seattle stops twice a day (once going north, once going south), make the west Ventura County stop here (east county stop is Simi Valley).

Bus

- Gold Coast Transit

- Operates local bus service in the city of Oxnard, Port Hueneme, Ventura, and Ojai. Its hub is the Oxnard Transit Center.[90]

- VISTA

- Operates 3 Conejo Connection buses during peak hours, towards the Warner Center Transit Hub in Los Angeles, connecting with the Metro Orange Line. The Conejo Connection does not go to the Oxnard Transit Center, but instead stops at the Esplanade Shopping Center near Highway 101.[91] VISTA also operates the Coastal Connection through Ventura towards Santa Barbara and Goleta from the Esplanade.[92]

A smaller transfer center sits at the Centerpoint Mall on C Street, which Gold Coast Transit sends most of their South Oxnard and Port Hueneme routes out from. VISTA also operates the Oxnard-CSUCI route that goes to California State University, Channel Islands and Oxnard College from this transfer center.[93]

Notable people

Political and cultural

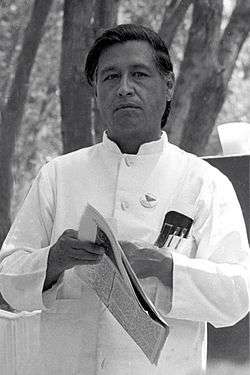

- César Chávez: farm worker, political activist and union leader, lived in the Colonia area of Oxnard during his childhood. Several streets and schools in the Oxnard area and surrounding areas bear his name. A home he lived in is on Wright Road in the El Rio neighborhood, northwest of Highway 101 and Rose Avenue, where Chavez lived with his family in the late 1950s while working as an advocate for local farmworkers. Also the office of the National Farm Workers Association - which later became United Farm Workers — on Cooper Road, east of Garfield Avenue in the La Colonia neighborhood. The Oxnard office opened in 1966, the year of a historic march from Delano to Sacramento.[94][95]

- William Soo Hoo: elected as mayor of Oxnard in 1966-70 and considered the first Chinese-American political leader of a major California city[96] and possibly the United States.[97][98]

- Lupe Anguiano: former nun and civil rights activist known for her work on women's rights, the rights of the poor, and the protection of the environment.

- William P. Clark: politician, served under President Ronald Reagan as the Deputy Secretary of State from 1981 to 1982, United States National Security Advisor from 1982 to 1983, and the Secretary of the Interior from 1983 until 1985.

- Nao Takasugi: California State Assembly and mayor of Oxnard.

- Jean Harris: credited with protecting Ormond Beach Wetlands and Oxnard State Beach.

- Alfred V. Rascon: awarded the Medal of Honor—the United States' highest military decoration.

Authors

- Gilbert, Jaime, and Mario Hernandez: creators of the black and white independent comic Love and Rockets.

- Joyce La Mers, author of light poetry.

- Michele Serros, author, writer for the George Lopez TV series.

Musicians and entertainers

- Madlib: Oxnard-based record producer, musician, rapper, and DJ noted for his work and collaborations in the jazz and hip-hop scenes

- Oh No: hip-hop rapper, producer and brother of Madlib who is signed to Stones Throw Records

- DJ Babu: Filipino American disc jockey for the Beat Junkies and Dilated Peoples

- Down AKA Kilo: rapper

- Homer Keller: composer (1915–1996)

- Ill Repute: hardcore punk band and leaders of the Nardcore movement

- Sonny Bono & Cher: Record producers, singers, actors; famous for Sonny & Cher pop duo and TV series, had a beach home in Oxnard Shores, Oxnard[99]

- Rich Moore: Academy Award-winning animation director (The Simpsons), and co-owner of Rough Draft Studios, Inc.

- The Warriors: hardcore band

- Dave Grohl: musician

- Shirley Verrett: operatic mezzo-soprano, 1931–2010

- Brooke Candy: rapper

- Ritchie Blackmore: guitarist with Deep Purple and founder of Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow.

- Steve Zaragoza: internet personality, comedian, and host on SourceFed.

- Anderson .Paak: rapper, singer, songwriter, drummer. Gaining recognition through recent feature on Dr. Dre's album "Compton".

- Nails: powerviolence band

Scholars and scientists

- William Bright: Linguist.

- J. Richard Chase, President of Biola University and Wheaton College

Business people

- Martin V. ("Bud") Smith: developer and philanthropist. The most significant developer in the Oxnard area. Built the Financial Plaza Towers and financed construction of CSUCI's school of business and economics. His first real estate project was the Wagon Wheel Motel & Restaurant and Wagon Wheel Junction.[100][101]

Actors and TV personalities

- Sonny Bono & Cher, actors, singers, had a beach house in Oxnard Shores, Oxnard.

- Walter Brennan, actor, three-time winner of Academy Award, star of TV series The Real McCoys and The Guns of Will Sonnett, died in Oxnard.

- John Carradine, actor, lived in Oxnard for many years.

- Charlie Chaplin, actor and director.

- Lee Van Cleef, actor, died in Oxnard.

- Jeffrey Combs, actor.

- Brandon Cruz, child actor and lead singer of the punk band Dr. Know, has family and a beach home in Oxnard.

- Clark Gable, actor and Carol Lombard, actress, had a beach house at Hollywood Beach, Oxnard.

- John Curtis Holmes, pornographic film star of the 1970s, had ashes scattered at sea off the coast of Oxnard in 1988.

- George Kennedy, Oscar-winning actor, has a beach house in Oxnard.

- Isiah Mustafa, the "Old Spice Guy," former NFL player.

- Donna Reed, Oscar-winning actress, The Donna Reed Show, Dallas, had a beach home at the Colony, Mandalay Beach, Oxnard.

- Pat Sajak, host of television game show Wheel of Fortune, had a beach house in Oxnard.

- Bob Stephenson, actor, film producer and screenwriter.

- Rudolph Valentino, silent-film actor.

Athletes and sportspeople

In alphabetical order by last name:

- Bobby Ayala: former Major League Baseball pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds, Seattle Mariners, Chicago Cubs and Montreal Expos; graduated from Rio Mesa High School.

- Mark Berry: coach for the Cincinnati Reds; graduated from Hueneme High School.

- The Bryan brothers: professional ATP tennis doubles players who have graduated from Rio Mesa High School.

- Lorenzo Booker: NFL running back.

- Graciela Casillas: boxer and kickboxer.

- Keary Colbert: wide receiver for the Seattle Seahawks; all-time reception leader for USC Trojans; graduated from Hueneme High School.

- Jacob Cruz: outfielder for the Cincinnati Reds; graduated from Channel Islands High School.

- Tim Curran: professional surfer; graduated from Oxnard High School.

- Lou Cvijanovich: winningest coach in California high school history; coached Santa Clara High School to 829 wins 1958–1999.

- Justin De Fratus: relief pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies, grew up in Oxnard, attended Rio Mesa High and Ventura Junior College.

- Charles Dillon: wide receiver for Green Bay Packers; played for Ventura College and Washington State; graduated from Hueneme High School in '04

- Terrance Dotsy: football player.

- Scott Fujita: NFL linebacker for the Cleveland Browns; graduated from Rio Mesa High School and University of California, Berkeley.

- Robert Garcia: retired professional boxer; former IBF Super Featherweight Champion.

- Phil Giebler: race car driver, won Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year award for 2007.

- Jim Hall: race car driver; two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500.

- Jeremy Jackson : pro UFC fighter, winner of King of the Mountain 2004, contestant in Ultimate Fighter 4 : The Comeback.

- Ronney Jenkins: 2001 NFL Pro Bowl kick returner for the San Diego Chargers; graduated from Hueneme High School.

- Nicole Johnson: Monster Jam monster truck driver; graduated from Rio Mesa High School

- Marion Jones: athlete, disqualified multiple Olympic gold medalist, attended and ran for Rio Mesa High School

- Dave Laut: retired shot putter; born in Findlay, Ohio, died August 27, 2009 in Oxnard.

- Whitney Lewis: former USC Trojans and University of Northern Iowa wide receiver; won 2003 Glenn Davis Award for top player in Southern California.

- Kristal Marshall: professional wrestler formerly with the World Wrestling Entertainment.

- Sergio Gabriel Martinez: boxer, based in Oxnard.

- Paul McAnulty: Major League Baseball outfielder with the San Diego Padres.

- Ken McMullen: former Major League Baseball third baseman with the Los Angeles Dodgers; was born in Oxnard.

- Victor Ortíz: professional boxer.

- Mike Parrott, professional baseball player and coach; born in Oxnard.

- Corey Pavin: professional golfer; winner of many tournaments including 1995 U.S. Open; graduated from Oxnard High School.[102]

- Terry Pendleton: retired baseball player, 1991 National League MVP; graduated from Channel Islands High School.

- Josh Pinkard: free safety for two-time national champion University of Southern California football team; graduated from Hueneme High School.

- Brandon Rios: professional boxer, the current WBA World lightweight champion.

- Jacob Rogers: offensive tackle for the Denver Broncos, three-year starter and All-American at USC; graduated from Oxnard High School.[103]

- Blaine Saipaia: football player for the St. Louis Rams; graduated from Channel Islands High School.

- Paul Stankowski: professional golfer; graduated from Hueneme High School.

- Kevin Thomas: former National Football League cornerback for the Buffalo Bills, graduated from Rio Mesa High School.

- Josh Towers: pitcher for the Toronto Blue Jays; graduated from Hueneme High School and Oxnard College.

- Steve Trachsel: pitcher for the Baltimore Orioles and four other MLB teams; was born in Oxnard and attended Hathaway Elementary.

- Fernando Vargas: retired boxer, two-time light-middleweight boxing champion; graduated from Channel Islands High School.

- Dmitri Young, baseball player for the Washington Nationals; graduated from Rio Mesa High School.

Sister cities

-

Ocotlán, Jalisco (Mexico)[104]

Ocotlán, Jalisco (Mexico)[104]

See also

- Largest cities in Southern California

- Oxnard Air Force Base

- Oxnard, California−related topics

Notes

- ↑ "Oxnard". City of Oxnard. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "California Cities by Incorporation Date" (Word). California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "City Council Members". City of Oxnard. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "City Clerk". City of Oxnard. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ "City Manager". City of Oxnard. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files – Places – California". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Oxnard". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Oxnard (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ↑ "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ "New York City tops in population; 8 more cities above 1M - The Business Journals". Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ Sauter, Michael B. ; Hess, Alexander E.M.; Weigley, Sam "America's Richest Cities: 24/7 Wall St." Huffington Post: Business. 07 October 2012. This article refers to the entire Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

- ↑ "Richest Cities in the US - Top 10 List". Techscio.com. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ "National Weather Service Los Angeles/Oxnard". Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ Clerici, Kevin (2011-03-23). "Demolition begins on Wagon Wheel Motel and Restaurant". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- ↑ Miller, Gregg (January 1, 1995). "Bud Smith's Empire 54 Years in the Making and No End in Sight". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Wilson, Kathleen (September 10, 2015). "Developer negotiating to open Hyatt hotel at Channel Islands Harbor". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ↑ "Oxnard Police Department News - Gang Injunction". October 16, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- ↑ Saillant, Catherine; Alvarez, Fred (April 26, 2005). "Judge Favors Permanent Gang Ban". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Saillant, Catherine (September 20, 2006). "Zone Is OKd to Limit Oxnard Gang". Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 "National Collection of Imperiled Plants". Centerforplantconservation.org. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ↑ Warchol, Richard (July 12, 1997). "Swimmer Lost Off Oxnard Beach". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Surf Zone Forecast". National Weather Service. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Distance from Oxnard, CA to Moorpark, CA by car, bike, walk". www.usageo.org. USAGeo.org. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "MPAcorn.com". MPAcorn.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Winton, Richard (16 October 2009). "Magnitude 3.2 earthquake is reported near Oxnard [Updated]". LA Times Blogs - L.A. NOW. Tribune Publishing Company. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ D, G (October 17, 2009). "Earthquake Hits Ventura County Near Oxnard". Thaindian News. Thaindian News. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Avila, Willian (Dec 1, 2014). "Magnitude-2.7 Quake Strikes Off Oxnard Coast". NBC Southern California. NBCUniversal Media, LLC. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Times, Los Angeles (April 6, 2016). "Earthquake: 3.5 quake strikes near Channel Islands Beach". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times Media Group. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Oxnard Climate". NOAA. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ↑ "CA Camarillo AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.wildlifeanimalcontrol.com/Oxnard.html

- ↑ Wolch, West and Gaines Transspecies Urban Theory from Satiety and Space 1995. volume 13, pages 735-760

- ↑ "Not One More Power Plant on Oxnard's Coast". caleja.org. California Environmental Justice Alliance. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ "Proposed Puente Power Plant in Oxnard". www.environmentaldefensecenter.org. » Environmental Defense Center. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "California Energy Commission Informational Hearing for the proposed "Puente" Energy Facility Application" (PDF). California Energy Commission. State of California. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Morales, Maricela (12 July 2015). "Not one more power plant in Oxnard". causenow.org. CAUSE. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Miller, George (22 May 2015). "Oxnard extends power plant moratorium another year; NRG states its case". citizensjournal.us, KADYTV. Citizensjournal.us. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- 1 2 Gross, Lisa. "How Data Reporting Can Help You Find New Angles On Environmental Health Stories". www.centerforhealthjournalism.org. Center for Health Jouranlism. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Gross, Liza (6 April 2015). "Fields of Toxic Pesticides Surround the Schools of Ventura County". Food and Environment Reporting Network. Food & Environment Reporting Network, Inc. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Garcia, Robert (29 August 2013). "Three Generations Sue U.S. EPA over Toxic Pesticides at Schools". KCET. KCETLink Media Group. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Craven, Jackie. "How One Town Saved its Crumbling Homes". About.com Home. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- 1 2 Benny M. and Rosanne Moss (June 8, 1998). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Henry T. Oxnard Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. and accompanying 140 photos

- 1 2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places.

- ↑ "Section 1 of the General 2030 Plan for Oxnard". Granicus. p. 1-1. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ "Section 3 of Oxnard 2030 General Plan". Granicus. pp. 3–12 and 3–13. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ "Section 3 of the General 2030 Plan for Oxnard". Granicus. p. 3-1. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ Bentley, Amy (July 19, 2009). "Crafty couple restores house in Oxnard Historic District". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Ormond Restoration Project". California Coastal Conservatory. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Ormond Beach". California Beaches. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ Kelley, Daryl (April 29, 2001) "Illness Forces Environmental Crusader to Sidelines." Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Oxnard city". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Oxnard (city), California". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ "California - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "City of Oxnard CAFR" (PDF). Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "City Of Oxnard — City of Oxnard Site" (PDF). Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Borla.com". Borla.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Robbinsautotop.com". Robbinsautotop.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "City of Camarillo General Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- ↑ Archived February 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived October 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Strawberry-fest.org". Strawberry-fest.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Kallas, Anne (May 17, 2015). "Excitement continues at Day 2 of Strawberry Fest". Ventura County Star.

- ↑ Archived March 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Murphyautomuseum.org". Murphyautomuseum.org. May 1, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "TFAOI.com". TFAOI.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Oxnardhistoricdistrict.com". Oxnardhistoricdistrict.com. February 5, 1999. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Pitter, Laura (September 3, 1990). "OXNARD : Heritage Square Receives Last House". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Woodard, Josef (November 7, 1991). "STRUCTURES : Houses of History : Heritage Square is one of the more surreal estates in Ventura County. It harks back to Oxnard's more glorious past.". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Oxnartourism.com". Oxnardtourism.com. March 20, 2011. Archived from the original on November 28, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Oxnardtourism.com". Oxnardtourism.com. January 1, 1999. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Oxnardpacc.com". Oxnardpacc.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Newwestsymphony.org". Newwestsymphony.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Oxnardfilmfest.com". Oxnardfilmfest.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Tallshipschannelislands.com". Tallshipschannelislands.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Herzogwinery.com". Herzogwinecellars.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Leo (August 14, 2015). "Touchdown Oxnard: Often-overlooked town scores with Dallas Cowboys camp and other draws". The Orange County Register. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Buttitta, Bob (August 20, 2011). "New Orleans Saints head to Oxnard for a week of training". Ventura County Star.

- ↑ Archived June 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ List of the largest school districts in the United States by enrollment

- ↑ "Oxnard School District".

- ↑ "Oceanviewsd.org". Oceanviewsd.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Riok12.ca.us". Riok12.ca.us. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Cathcart, Rebecca (February 23, 2008). "Boy's Killing, Labeled a Hate Crime, Stuns a Town". New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Covarrubias, Amanda (July 22, 2016). "Trade is key topic of meeting between Mexican consul, Oxnard mayor". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "Current Schedules". Goldcoasttransit.org. 2016-01-24. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ "VCTC Highway 101 & Conejo Connection Northbound Weekday". GoVentura. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ↑ "VCTC CSUCI Oxnard Weekday". GoVentura. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ Wenner, Gretchen (October 29, 2011) "Oxnard sites on list of historic places linked to Cesar Chavez" Ventura County Star

- ↑ Alvarez, Fred (May 28, 1993) "Chavez Home In Oxnard Was Razed Years Ago : La Colonia: Mourners mistakenly visited a dwelling next to the site where the late labor leader lived as a boy." Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Bentz, Linda; Gow, William (2012). "5". Hidden Lives: A Century of Chinese American History in Ventura County. Palos Verdes Estates, CA: Pacific Heritage Books. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1928753-67-4.

- ↑ Maulhardt, Jeffrey Wayne (2013). Legendary Locals of Oxnard. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4671-0056-4.

- ↑ Storer, Mark (July 21, 2016). "Local residents add to Smithsonian exhibit in Ventura". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

...Oxnard Mayor Bill Soo Hoo, who served as the first Chinese-American mayor in California.

- ↑ "Oxnard, The Other Hollywood – Oxnard Vacation". Beachcalifornia.com. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ Mitchell, John (November 20, 2001). "Influential developer Martin 'Bud' Smith dies". Ventura County Star.

- ↑ Shepherd, Dirk (January 11, 2007). "Save the Wagon Wheel". VC Reporter.

- ↑ "Corey Pavin". PGA Tour. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Romine, Rich (June 3, 2011). "Longtime Ventura County football coach J.T. Rogers dies". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Leung, Wendy (August 21, 2016). "Oxnard council members return from overseas trips touting city". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

References

- Hoad, Patricia; et al. (Spring–Summer 2002). Oxnard at 100, The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly. Ventura County Museum of History & Art. pp. 6–49. ISSN 0042-3491.

- Maulhardt, Jeffrey W. (2005). Oxnard 1941–2004. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7, 19, 28, 58, 63, 66, 68, 70, 78, 79, 81. ISBN 978-0-7385-2953-0.

- Gutleben, Dan, The Oxnard Beet Sugar Factory, Oxnard, California, 1959 – Revised 1960, page 1, Book available at the Oxnard Public Library

Further reading

- Frank P. Barajas, Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard, California, 1898-1961. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

External links

|

Ventura Santa Barbara U.S. 101 PCH1 |

Ventura | Saticoy Santa Paula SR 126 via SR 232 and SR 118 |

|

| Pacific Ocean | |

Camarillo U.S. 101 | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Port Hueneme | Malibu PCH1 |