Nation state

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

.jpg)

A nation state is a type of state that joins the political entity of a state to the cultural entity of a nation, from which it aims to derive its political legitimacy to rule and potentially its status as a sovereign state if one accepts the declarative theory of statehood as opposed to the constitutive theory.[1] A state is specifically a political and geopolitical entity, whilst a nation is a cultural and ethnic one. The term "nation state" implies that the two coincide, in that a state has chosen to adopt and endorse a specific cultural group as associated with it. "Nation state" formation can take place at different times in different parts of the world.

The concept of a nation state can be compared and contrasted with that of the multinational state, city state,[2][3][4] empire, confederation, and other state formations with which it may overlap. The key distinction is the identification of a people with a polity in the "nation state."

History and origins

The origins and early history of nation states are disputed. A major theoretical question is: "Which came first, the nation or the nation state?" Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, and Jeremy Black[5][6] have advanced the hypothesis that the nation state didn't arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it an accident of history or political invention; but is an inadvertent byproduct of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy, capitalism, mercantilism, political geography, and geography[7][8] combined together with cartography[9][10] and advances in map-making technologies.[11][12] It was with these intellectual discoveries and technological advances that the nation state arose. For others, the nation existed first, then nationalist movements arose for sovereignty, and the nation state was created to meet that demand. Some "modernization theories" of nationalism see it as a product of government policies to unify and modernize an already existing state. Most theories see the nation state as a 19th-century European phenomenon, facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy and mass media. However, historians also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal and the Dutch Republic.

In France, Eric Hobsbawm argues, the French state preceded the formation of the French people. Hobsbawm considers that the state made the French nation, not French nationalism, which emerged at the end of the 19th century, the time of the Dreyfus Affair. At the time of the 1789 French Revolution, only half of the French people spoke some French, and 12-13% spoke it "correctly", according to Hobsbawm.[13]

During the Italian unification, the number of people speaking the Italian language was even lower. The French state promoted the unification of various dialects and languages into the French language. The introduction of conscription and the Third Republic's 1880s laws on public instruction, facilitated the creation of a national identity, under this theory.

Some nation states, such as Germany or Italy, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists, during the 19th century. In both cases, the territory was previously divided among other states, some of them very small. The sense of common identity was at first a cultural movement, such as in the Völkisch movement in German-speaking states, which rapidly acquired a political significance. In these cases, the nationalist sentiment and the nationalist movement clearly precede the unification of the German and Italian nation states.

Historians Hans Kohn, Liah Greenfeld, Philip White and others have classified nations such as Germany or Italy, where cultural unification preceded state unification, as ethnic nations or ethnic nationalities. However, 'state-driven' national unifications, such as in France, England or China, are more likely to flourish in multiethnic societies, producing a traditional national heritage of civic nations, or territory-based nationalities.[14][15][16] Some authors deconstruct the distinction between ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism because of the ambiguity of the concepts. They argue that the paradigmatic case of Ernest Renan is an idealisation and it should be interpreted within the German tradition and not in opposition to it. For example, they argue that the arguments used by Renan at the conference What is a nation? are not consistent with his thinking. This alleged civic conception of the nation would be determined only by the case of the loss gives Alsace and Lorraine in the Franco-Prussian War.[17]

The idea of a nation state was and is associated with the rise of the modern system of states, often called the "Westphalian system" in reference to the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). The balance of power, which characterized that system, depended on its effectiveness upon clearly defined, centrally controlled, independent entities, whether empires or nation states, which recognize each other's sovereignty and territory. The Westphalian system did not create the nation state, but the nation state meets the criteria for its component states (by assuming that there is no disputed territory).

The nation state received a philosophical underpinning in the era of Romanticism, at first as the 'natural' expression of the individual peoples (romantic nationalism: see Johann Gottlieb Fichte's conception of the Volk, later opposed by Ernest Renan). The increasing emphasis during the 19th century on the ethnic and racial origins of the nation, led to a redefinition of the nation state in these terms.[16] Racism, which in Boulainvilliers's theories was inherently antipatriotic and antinationalist, joined itself with colonialist imperialism and "continental imperialism", most notably in pan-Germanic and pan-Slavic movements.[18]

The relation between racism and ethnic nationalism reached its height in the 20th century fascism and Nazism. The specific combination of 'nation' ('people') and 'state' expressed in such terms as the Völkische Staat and implemented in laws such as the 1935 Nuremberg laws made fascist states such as early Nazi Germany qualitatively different from non-fascist nation states. Minorities were not considered part of the people (Volk), and were consequently denied to have an authentic or legitimate role in such a state. In Germany, neither Jews nor the Roma were considered part of the people, and were specifically targeted for persecution. German nationality law defined 'German' on the basis of German ancestry, excluding all non-Germans from the people.

In recent years, a nation state's claim to absolute sovereignty within its borders has been much criticized.[16] A global political system based on international agreements and supra-national blocs characterized the post-war era. Non-state actors, such as international corporations and non-governmental organizations, are widely seen as eroding the economic and political power of nation states, potentially leading to their eventual disappearance.

Before the nation state

In Europe, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multiethnic empires, the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of France, Kingdom of Hungary,[19] the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire and smaller nations at what would now be called sub-state level. The multi-ethnic empire was a monarchy ruled by a king, emperor or sultan. The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty was usually, but not always, from that group.

This type of state is not specifically European: such empires existed on all continents, except Australasia and Antarctica. Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse, but were also dynastic states, ruled by a royal house. Their territory could expand by royal intermarriage or merge with another state when the dynasty merged. In some parts of Europe, notably Germany, very small territorial units existed. They were recognised by their neighbours as independent, and had their own government and laws. Some were ruled by princes or other hereditary rulers, some were governed by bishops or abbots. Because they were so small, however, they had no separate language or culture: the inhabitants shared the language of the surrounding region.

In some cases these states were simply overthrown by nationalist uprisings in the 19th century. Liberal ideas of free trade played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. However, the Austro-Prussian War, and the German alliances in the Franco-Prussian War, were decisive in the unification. The Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire broke up after the First World War, and the Russian Empire became the Soviet Union after the Russian Civil War.

A few of the smaller states survived: the independent principalities of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, and the republic of San Marino. (Vatican City is a special case. All of the larger Papal State save the Vatican itself was occupied and absorbed by Italy by 1870. The resulting Roman Question, was resolved with the rise of the modern state under the 1929 Lateran treaties between Italy and the Holy See.)

Characteristics

"Legitimate states that govern effectively and dynamic industrial economies are widely regarded today as the defining characteristics of a modern nation-state."[20]

Nation states have their own characteristics, differing from those of the pre-national states. For a start, they have a different attitude to their territory when compared with dynastic monarchies: it is semisacred and nontransferable. No nation would swap territory with other states simply, for example, because the king's daughter married. They have a different type of border, in principle defined only by the area of settlement of the national group, although many nation states also sought natural borders (rivers, mountain ranges). They are constantly changing in population size and power because of the limited restrictions of their borders.

The most noticeable characteristic is the degree to which nation states use the state as an instrument of national unity, in economic, social and cultural life.

The nation state promoted economic unity, by abolishing internal customs and tolls. In Germany, that process, the creation of the Zollverein, preceded formal national unity. Nation states typically have a policy to create and maintain a national transportation infrastructure, facilitating trade and travel. In 19th-century Europe, the expansion of the rail transport networks was at first largely a matter for private railway companies, but gradually came under control of the national governments. The French rail network, with its main lines radiating from Paris to all corners of France, is often seen as a reflection of the centralised French nation state, which directed its construction. Nation states continue to build, for instance, specifically national motorway networks. Specifically transnational infrastructure programmes, such as the Trans-European Networks, are a recent innovation.

The nation states typically had a more centralised and uniform public administration than its imperial predecessors: they were smaller, and the population less diverse. (The internal diversity of the Ottoman Empire, for instance, was very great.) After the 19th-century triumph of the nation state in Europe, regional identity was subordinate to national identity, in regions such as Alsace-Lorraine, Catalonia, Brittany and Corsica. In many cases, the regional administration was also subordinated to central (national) government. This process was partially reversed from the 1970s onward, with the introduction of various forms of regional autonomy, in formerly centralised states such as France.

The most obvious impact of the nation state, as compared to its non-national predecessors, is the creation of a uniform national culture, through state policy. The model of the nation state implies that its population constitutes a nation, united by a common descent, a common language and many forms of shared culture. When the implied unity was absent, the nation state often tried to create it. It promoted a uniform national language, through language policy. The creation of national systems of compulsory primary education and a relatively uniform curriculum in secondary schools, was the most effective instrument in the spread of the national languages. The schools also taught the national history, often in a propagandistic and mythologised version, and (especially during conflicts) some nation states still teach this kind of history.[21]

Language and cultural policy was sometimes negative, aimed at the suppression of non-national elements. Language prohibitions were sometimes used to accelerate the adoption of national languages and the decline of minority languages (see examples: Anglicisation, Czechization, Francisation, Italianization, Germanisation, Magyarisation, Polonisation, Russification, Serbization, Slovakisation).

In some cases, these policies triggered bitter conflicts and further ethnic separatism. But where it worked, the cultural uniformity and homogeneity of the population increased. Conversely, the cultural divergence at the border became sharper: in theory, a uniform French identity extends from the Atlantic coast to the Rhine, and on the other bank of the Rhine, a uniform German identity begins. To enforce that model, both sides have divergent language policy and educational systems, although the linguistic boundary is in fact well inside France, and the Alsace region changed hands four times between 1870 and 1945.

In practice

In some cases, the geographic boundaries of an ethnic population and a political state largely coincide. In these cases, there is little immigration or emigration, few members of ethnic minorities, and few members of the "home" ethnicity living in other countries.

Examples of nation states where ethnic groups make up more than 95% of the population include the following:

- Albania: The vast majority of the population is ethnically Albanian at about 98.6% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities.

- Armenia: The vast majority of Armenia's population consists of ethnic Armenians at about 98% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities.

- Bangladesh: The vast majority ethnic group of Bangladesh are the Bengali people, comprising 98% of the population, with the remainder consisting of mostly Bihari migrants and indigenous tribal groups. Therefore, Bangladeshi society is to a great extent linguistically and culturally homogeneous, with very small populations of foreign expatriates and workers, although there is a substantial number of Bengali workers living abroad.

- Egypt: The vast majority of Egypt's population consists of ethnic Egyptians at about 99% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities, as well as refugees or asylum seekers. Modern Egyptian identity is closely tied to the geography of Egypt and its long history; its development over the centuries saw overlapping or conflicting ideologies. Though today an Arabic-speaking people, that aspect constitutes for Egyptians a cultural dimension of their identity, not a necessary attribute of or prop for their national political being. Today most Egyptians see themselves, their history, culture and language (the Egyptian variant of Arabic) as specifically Egyptian and at the same time as part of the Arab world.

- Estonia: Defined as a nation state in its 1920 constitution, up until the period of Soviet colonialisation, Estonia was historically a very homogenous state with 88.2% of residents being Estonians, 8.2% Russians, 1.5% Germans and 0.4% Jews according to the 1934 census.[22][23] As a result of Soviet policies the demographic situation significantly changed with the arrival of Russian speaking settlers. Today Estonians form 69%, Russians 25.4%, Ukrainians 2.04% and Belarusians 1.1% of the population(2012).[24] A significant proportion of the inhabitants (84.1%) are citizens of Estonia, around 7.3% are citizens of Russia and 7.0% as yet undefined citizenship (2010).[22][24]

- Hungary: The Hungarians (or Magyar) people consist of about 95% of the population, with a small Roma and German minority: see Demographics of Hungary.

- Iceland: Although the inhabitants are ethnically related to other Scandinavian groups, the national culture and language are found only in Iceland. There are no cross-border minorities as the nearest land is too far away: see Demographics of Iceland

- Japan: Japan is also traditionally seen as an example of a nation state and also the largest of the nation states, with population in excess of 120 million. It should be noted that Japan has a small number of minorities such as Ryūkyū peoples, Koreans and Chinese, and on the northern island of Hokkaidō, the indigenous Ainu minority. However, they are either numerically insignificant (Ainu), their difference is not as pronounced (though Ryukyuan culture is closely related to Japanese culture, it is nonetheless distinctive in that it historically received much more influence from China and has separate political and nonpolitical and religious traditions) or well assimilated (Zainichi population is collapsing due to assimilation/naturalisation).

- Lebanon: The Arabic-speaking Lebanese consist at about 95% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities, as well as refugees or asylum seekers. Modern Lebanese identity is closely tied to the geography of Lebanon and its history. Although they are now an Arabic-speaking people and ethnically homogeneous, its identity oversees overlapping or conflicting ideologies between its Phoenician heritage and Arab heritage. While many Lebanese regard themselves as Arab, other Lebanese regard themselves, their history, and their culture as Phoenician and not Arab, while still other Lebanese regard themselves as both.

- Lesotho: Lesotho's ethno-linguistic structure consists almost entirely of the Basotho (singular Mosotho), a Bantu-speaking people; about 99.7% of the population are Basotho.

- Maldives: The vast majority of the population is ethnically Dhivehi at about 98% of the population, with the remainder consisting of foreign workers; there are no indigenous ethnic minorities.

- Malta: The vast majority of the population is ethnically Maltese at about 95.3% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities.

- Mongolia: The vast majority of the population is ethnically Mongol at about 95.0% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few ethnic minorities included in Kazakhs.

- North and South Korea are among the most ethnically and linguistically homogeneous in the world. Particularly in reclusive North Korea, there are very few ethnic minority groups and expatriate foreigners.

- Poland: After World War II, with the genocide of the Jews by the invading German Nazis during the Holocaust, the expulsion of Germans after World War II and the loss of eastern territories (Kresy), 96.7% of the people of Poland claim Polish nationality, while 97.8% declare that they speak Polish at home (Census 2002).

- Several Polynesian countries such as Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, etc.

- Portugal: Although surrounded by other lands and people, the Portuguese nation has occupied the same territory since the romanization or latinization of the native population during the Roman era. The modern Portuguese nation is a very old amalgam of formerly distinct historical populations that passed through and settled in the territory of modern Portugal: native Iberian peoples, Celts, ancient Mediterraneans (Greeks, Phoenicians, Romans, Jews), invading Germanic peoples like the Suebi and the Visigoths, and Muslim Arabs and Berbers. Most Berber/Arab people and the Jews were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula during the Reconquista and the repopulation by Christians.

- San Marino: The Sammarinese make up about 97% of the population and all speak Italian and are ethnically and linguisticially identical to Italians. San Marino is a landlocked enclave, completely surrounded by Italy. The state has a population of approximately 30,000, including 1,000 foreigners, most of whom are Italians.

- Swaziland: The vast majority of the population is ethnically Swazi at about 98.6% of the population, with the remainder consisting of a few small ethnic minorities.

The notion of a unifying "national identity" also extends to countries that host multiple ethnic or language groups, such as India and China. For example, Switzerland is constitutionally a confederation of cantons, and has four official languages, but it has also a 'Swiss' national identity, a national history and a classic national hero, Wilhelm Tell.[25]

Innumerable conflicts have arisen where political boundaries did not correspond with ethnic or cultural boundaries.

After World War II in the Josip Broz Tito era, nationalism was appealed to for uniting South Slav peoples. Later in the 20th century, after the break-up of the Soviet Union, leaders appealed to ancient ethnic feuds or tensions that ignited conflict between the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, as well Bosnians, Montenegrins and Macedonians, eventually breaking up the long collaboration of peoples and ethnic cleansing was carried out in the Balkans, resulting in the destruction of the formerly socialist republic and produced the civil wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992–95, resulted in mass population displacements and segregation that radically altered what was once a highly diverse and intermixed ethnic makeup of the region. These conflicts were largely about creating a new political framework of states, each of which would be ethnically and politically homogeneous. Serbians, Croatians and Bosnians insisted they were ethnically distinct although many communities had a long history of intermarriage. Presently Slovenia (89% Slovene), Croatia (90,4% Croat)[26] and Serbia (83% Serb) could be classified as nation states per se, whereas Macedonia (66% Macedonian), Montenegro (42% Montenegrin) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (50.1% Bosniak) are multinational states.

Belgium is a classic example of a state that is not a nation state. The state was formed by secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830, whose neutrality and integrity was protected by the Treaty of London 1839; thus it served as a buffer state after the Napoleonitic Wars between the European powers France, Prussia (after 1871 the German Empire) and the United Kingdom until World War I, when its neutrality was breached by the Germans. Currently, Belgium is divided between the Flemings in the north and the French-speaking or the German-speaking population in the south. The Flemish population in the north speaks Dutch, the Walloon population in the south speaks French and/or German. The Brussels population speaks French and/or Dutch.

The Flemish identity is also cultural, and there is a strong separatist movement espoused by the political parties, the right-wing Vlaams Belang and the Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie. The Francophone Walloon identity of Belgium is linguistically distinct and regionalist. There is also unitary Belgian nationalism, several versions of a Greater Netherlands ideal, and a German-speaking community of Belgium annexed from Germany in 1920, and re-annexed by Germany in 1940–1944. However these ideologies are all very marginal and politically insignificant during elections.

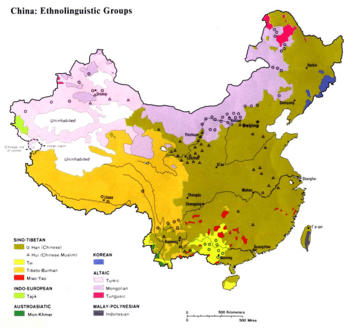

China covers a large geographic area and uses the concept of "Zhonghua minzu" or Chinese nationality, in the sense of ethnic groups, but it also officially recognizes the majority Han ethnic group which accounts for over 90% of the population, and no fewer than 55 ethnic national minorities.

According to Philip G. Roeder, Moldova is an example of a Soviet era "segment-state" (Moldavian SSR), where the "nation-state project of the segment-state trumped the nation-state project of prior statehood. In Moldova, despite strong agitation from university faculty and students for reunification with Romania, the nation-state project forged within the Moldavian SSR trumped the project for a return to the interwar nation-state project of Greater Romania."[28] See Controversy over linguistic and ethnic identity in Moldova for further details.

Exceptional cases

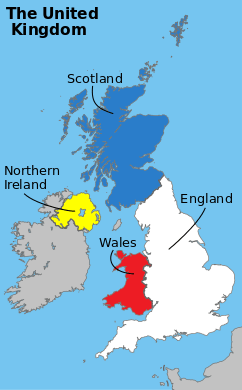

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is an unusual example of a nation state, due to its claimed "countries within a country" status. The United Kingdom, which is formed by the union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, is a unitary state formed initially by the merger of two independent kingdoms, the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland, but the Treaty of Union (1707) that set out the agreed terms has ensured the continuation of distinct features of each state, including separate legal systems and separate national churches.

In 2003, the British Government described the United Kingdom as "countries within a country".[29] While the Office for National Statistics and others describe the United Kingdom as a "nation state",[30][31] others, including a then Prime Minister, describe it as a "multinational state",[32][33][34] and the term Home Nations is used to describe the four national teams that represent the four nations of the United Kingdom (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales).[35]

Kingdom of the Netherlands

A similar unusual example is the Kingdom of the Netherlands. As of 10 October 2010, the Kingdom of the Netherlands consists of four countries:[36]

- Netherlands proper

- Aruba

- Curaçao

- Sint Maarten

Each is expressly designated as a land in Dutch law by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[37] Unlike the German Länder and the Austrian Bundesländer, landen is consistently translated as "countries" by the Dutch government.[38][39][40]

Israel

Israel was founded as a Jewish state in 1948. Its "Basic Laws" describe it as both a Jewish and a democratic state. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 75.7% of Israel's population is Jewish.[41] Arabs, who make up 20.4% of the population, are the largest ethnic minority in Israel. Israel also has very small communities of Armenians, Circassians, Assyrians, Samaritans, and persons of some Jewish heritage. There are also some non-Jewish spouses of Israeli Jews. However, these communities are very small, and usually number only in the hundreds or thousands.

Pakistan

Pakistan, even being an ethnically diverse country and officially a federation, is regarded as a nation state[42] due to its ideological basis on which it was given independence from British India as a separate nation rather than as part of a unified India. Different ethnic groups in Pakistan are strongly bonded by their common Muslim identity, common cultural and social values, common historical heritage, a national Lingua franca (Urdu) and joint political, strategic and economic interests.[42][43]

Minorities

The most obvious deviation from the ideal of 'one nation, one state', is the presence of minorities, especially ethnic minorities, which are clearly not members of the majority nation. An ethnic nationalist definition of a nation is necessarily exclusive: ethnic nations typically do not have open membership. In most cases, there is a clear idea that surrounding nations are different, and that includes members of those nations who live on the 'wrong side' of the border. Historical examples of groups, who have been specifically singled out as outsiders, are the Roma and Jews in Europe.

Negative responses to minorities within the nation state have ranged from cultural assimilation enforced by the state, to expulsion, persecution, violence, and extermination. The assimilation policies are usually enforced by the state, but violence against minorities is not always state initiated: it can occur in the form of mob violence such as lynching or pogroms. Nation states are responsible for some of the worst historical examples of violence against minorities not considered part of the nation.

However, many nation states accept specific minorities as being part of the nation, and the term national minority is often used in this sense. The Sorbs in Germany are an example: for centuries they have lived in German-speaking states, surrounded by a much larger ethnic German population, and they have no other historical territory. They are now generally considered to be part of the German nation and are accepted as such by the Federal Republic of Germany, which constitutionally guarantees their cultural rights. Of the thousands of ethnic and cultural minorities in nation states across the world, only a few have this level of acceptance and protection.

Multiculturalism is an official policy in many states, establishing the ideal of peaceful existence among multiple ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups. Many nations have laws protecting minority rights.

When national boundaries that do not match ethnic boundaries are drawn, such as in the Balkans and Central Asia, ethnic tension, massacres and even genocide, sometimes has occurred historically (see Bosnian genocide and 2010 ethnic violence in southern Kyrgyzstan).

Irredentism

Ideally, the border of a nation state extends far enough to include all the members of the nation, and all of the national homeland. Again, in practice some of them always live on the 'wrong side' of the border. Part of the national homeland may be there too, and it may be governed by the 'wrong' nation. The response to the non-inclusion of territory and population may take the form of irredentism: demands to annex unredeemed territory and incorporate it into the nation state.

Irredentist claims are usually based on the fact that an identifiable part of the national group lives across the border. However, they can include claims to territory where no members of that nation live at present, because they lived there in the past, the national language is spoken in that region, the national culture has influenced it, geographical unity with the existing territory, or a wide variety of other reasons. Past grievances are usually involved and can cause revanchism.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish irredentism from pan-nationalism, since both claim that all members of an ethnic and cultural nation belong in one specific state. Pan-nationalism is less likely to specify the nation ethnically. For instance, variants of Pan-Germanism have different ideas about what constituted Greater Germany, including the confusing term Grossdeutschland, which, in fact, implied the inclusion of huge Slavic minorities from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Typically, irredentist demands are at first made by members of non-state nationalist movements. When they are adopted by a state, they typically result in tensions, and actual attempts at annexation are always considered a casus belli, a cause for war. In many cases, such claims result in long-term hostile relations between neighbouring states. Irredentist movements typically circulate maps of the claimed national territory, the greater nation state. That territory, which is often much larger than the existing state, plays a central role in their propaganda.

Irredentism should not be confused with claims to overseas colonies, which are not generally considered part of the national homeland. Some French overseas colonies would be an exception: French rule in Algeria unsuccessfully treated the colony as a département of France.

Future

It has been speculated by both proponents of globalization and various science fiction writers that the concept of a nation state may disappear with the ever-increasing interconnectedness of the world.[16][44][45] Such ideas are sometimes expressed around concepts of a world government. Another possibility is a societal collapse and move into communal anarchy or zero world government, in which nation states no longer exist and government is done on the local level based on a global ethic of human rights.

This falls in line with the concept of internationalism, which states that sovereignty is an outdated concept and a barrier to achieving peace and harmony in the world.

Globalization especially has helped to bring about the discussion about the disappearance of nation states, as global trade and the rise of the concepts of a 'global citizen' and a common identity have helped to reduce differences and 'distances' between individual nation states, especially with regards to the internet.[46]

Clash of civilizations

The theory of the clash of civilizations lies in direct contrast to cosmopolitan theories about an ever more-connected world that no longer requires nation states. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world.

The theory was originally formulated in a 1992 lecture[47] at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?",[48] in response to Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy and capitalist free market economics had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man, argued that the world had reached a Hegelian "end of history".

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had reverted only to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural and religious lines.

As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest rank of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict.

In the 1993 Foreign Affairs article, Huntington writes:

- It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.[48]

Sandra Joireman suggests that Huntington may be characterised as a neo-primordialist, as, while he sees people as having strong ties to their ethnicity, he does not believe that these ties have always existed.[49]

Historiography

Historians often look to the past to find the origins of a particular nation state. Indeed, they often put so much emphasis on the importance of the nation state in modern times, that they distort the history of earlier periods in order to emphasize the question of origins. Lansing and English argue that much of the medieval history of Europe was structured to follow the historical winners—especially the nation states that emerged around Paris and London. Important developments that did not directly lead to a nation state get neglected, they argue:

- one effect of this approach has been to privilege historical winners, aspects of medieval Europe that became important in later centuries, above all the nation state.... Arguably the liveliest cultural innovation in the 13th century was Mediterranean, centered on Frederick II's polyglot court and administration in Palermo....Sicily and the Italian South in later centuries suffered a long slide into overtaxed poverty and marginality. Textbook narratives therefore focus not on medieval Palermo, with its Muslim and Jewish bureaucracies and Arabic-speaking monarch, but on the historical winners, Paris and London.[50]

See also

- Balkanization

- Bioregionalism as an alternative to nation states.

- Caliphate

- City-state

- Nation

- Nationalism

- National personification

- Titular nation

- Westphalian sovereignty

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. ISBN 0-86091-329-5 .

- Colomer, Josep M.. 2007. Great Empires, Small Nations. The Uncertain Future of the Sovereign State. ISBN 0-415-43775-X .

- Gellner, Ernest (1983). Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1662-0 .

- Hobsbawm, Eric J. (1992). Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43961-2.

- James, Paul (1996). Nation Formation: Towards a Theory of Abstract Community. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5072-9.

- Khan, Ali (1992). The Extinction of Nation states

- Renan, Ernest. 1882. "Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?" ("What is a Nation?")

- Malesevic, Sinisa (2006). Identity as Ideology: Understanding Ethnicity and Nationalism New York: Palgrave.

- Smith, Anthony D. (1986). The Ethnic Origins of Nations London: Basil Blackwell. pp 6–18. ISBN 0-631-15205-9.

- White, Philip L. (2006). "Globalization and the Mythology of the Nation State," In A.G.Hopkins, ed. Global History: Interactions Between the Universal and the Local Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–284.

Notes

- ↑ Such a definition is a working one: "All attempts to develop terminological consensus around "nation" resulted in failure", concludes Tishkov, Valery (2000). "Forget the 'nation': post-nationalist understanding of nationalism". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 23 (4): 625–650 [p. 627]. doi:10.1080/01419870050033658.. Walker Connor, in [Connor, Walker (1978). "A Nation is a Nation, is a State, is an Ethnic Group, is a...". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1 (4): 377–400. doi:10.1080/01419870.1978.9993240.] discusses the impressions surrounding the characters of "nation", "(sovereign) state", "nation state", and "nationalism". Connor, who gave the term "ethnonationalism" wide currency, also discusses the tendency to confuse nation and state and the treatment of all states as if nation states. In Globalization and Belonging, Sheila L. Crouche discusses "The Definitional Dilemma" (pp. 85ff).

- ↑ Peter Radan (2002). The break-up of Yugoslavia and international law. Psychology Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-415-25352-9. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ↑ Alfred Michael Boll (2007). Multiple nationality and international law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 978-90-04-14838-3. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ↑ Daniel Judah Elazar (1998). Covenant and civil society: the constitutional matrix of modern democracy. Transaction Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-56000-311-3. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ↑ Jeremy Black Maps and Politics pp.59-98 1998

- ↑ Maps and Politics pp.100-147 1998

- ↑ International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. Direct Georeferencing : A New Standard in Photogrammetry for High Accuracy Mapping Volume XXXIX pp.5-9 2012

- ↑ International Archives of the Photogrammetry On Borders:From Ancient to Postmodern Times Volume 40 pp.1-7 2013

- ↑ International Archives of the Photogrammetry Borderlines: Maps and the spread of the Westphalian state from Europe to Asia Part One –The European Context Volume 40 pp.111-116 2013

- ↑ International Archives of the Photogrammetry Appearance and Appliance of the Twin-Cities Concept on the Russian-Chinese Border Volume 40 pp.105-110 2013

- ↑ "How Maps Made the World". Wilson Quarterly. Summer 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

Source: 'Mapping the Sovereign State: Technology, Authority, and Systemic Change' by Jordan Branch, in International Organization, Volume 65, Issue 1, Winter 2011

- ↑ Branch, Jordan Nathaniel; advisor, Steven Weber (2011). "Mapping the Sovereign State: Cartographic Technology, Political Authority, and Systemic Change" (Ph.D.). Publication Number 3469226. University of California, Berkeley. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0020818310000299. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

Abstract: How did modern territorial states come to replace earlier forms of organization, defined by a wide variety of territorial and non-territorial forms of authority? Answering this question can help to explain both where our international political system came from and where it might be going....

- ↑ Hobsbawm, Eric (1992). Nations and nationalism since 1780 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0521439612.

- ↑ Kohn, Hans (1955). Nationalism: Its Meaning & History

- ↑ Greenfeld, Liah (1992). Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity

- 1 2 3 4 White, Philip L. (2006). 'Globalization and the Mythology of the Nation State', In A.G.Hopkins, ed. Global History: Interactions Between the Universal and the Local Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–284

- ↑ Azurmendi, Joxe: Historia, arraza, nazioa, Donostia: Elkar, 2014. ISBN 978-84-9027-297-8

- ↑ See Hannah Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

- ↑ ^ Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780 : programme, myth, reality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990; ISBN 0-521-43961-2) chapter II "The popular protonationalism", pp.80-81 French edition (Gallimard, 1992). According to Hobsbawm, the main source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927-1943, 13 volumes, in particular volume IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a widespread national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) ("The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic. Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- ↑ Kohli, Atul (2004). State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-54525-9.

- ↑ Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers Recommendation Rec(2001)15 on history teaching in 21st-century Europe (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 31 October 2001 at the 771st meeting of the Ministers' Deputies) and "UNITED for Intercultural Action". united.non-profit.nl.

|chapter=ignored (help) and Hobsbawm, Eric; Ranger, Terence (1992). The Invention of Tradition. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43773-3. Melman, Billie (1991). "Claiming the Nation's Past: The Invention of an Anglo-Saxon Tradition". Journal of Contemporary History. 26 (3/4): 575–595. doi:10.1177/002200949102600312. JSTOR 260661. Hughes, Christopher (1999). "Robert Stone Nation-Building and Curriculum Reform in Hong Kong and Taiwan". China Quarterly. 160: 977–991. doi:10.1017/s0305741000001405. - 1 2 Kalekin-Fishman, D.; Pirkko Pitkänen (2006). Multiple Citizenship as a Challenge to European Nation-States. Sense Publishers. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-77874-86-8.

- ↑ Ajalugu, Eesti; Zetterberg, Seppo (2001). p. 601. OCLC 948319961. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 "Rahvaarv rahvuse järgi, 1. jaanuar, aastad". stat.ee. 2001–2010.

- ↑ Thomas Riklin, 2005. Worin unterscheidet sich die schweizerische "Nation" von der Französischen bzw. Deutschen "Nation"?

- ↑ "Central Bureau of Statistics". www.dzs.hr. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ↑ Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1983. The map shows the distribution of ethnolinguistic groups according to the historical majority ethnic groups by region. Note this is different from the current distribution due to age-long internal migration and assimilation.

- ↑ Philip G. Roeder (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princeton University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3.

- ↑ "Countries within a country, number10.gov.uk". Webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. 10 January 2003. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "ONS Glossary of economic terms". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Giddens, Anthony (2006). Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7456-3379-4.

- ↑ Hogwood, Brian. "Regulatory Reform in a Multinational State: The Emergence of Multilevel Regulation in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ "Gordon Brown: We must defend the Union". telegraph.co.uk. 25 March 2008.

- ↑ "DIVERSITY AND CITIZENSHIP CURRICULUM REVIEW" (PDF). www.devon.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ Magnay, Jacquelin (26 May 2010). "London 2012: Hugh Robertson puts Home Nations football team on agenda". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ "Netherlands Antilles no more — Stabroek News — Guyana". Stabroek News. 9 October 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Article 1 of the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands". Lexius.nl. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations -Aruba". English.minbzk.nl. 24 January 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "St Martin News Network". smn-news.com. 18 November 2010.

- ↑ "Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations — New Status". English.minbzk.nl. 1 October 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Israel at 62: Population of 7,587,000". Ynet.co.il. 20 June 1995. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- 1 2 Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan

- ↑ Mahomed Ali Jinnah (1992) [originally published 1940], Problem of India's future constitution, and allied articles, Minerva Book Shop, Anarkali, Lahore, ISBN 978-969-0-10122-8,

... understood in the West, by a Hindu or a Muslim, but a complete social order which affects all the activities in life. In Islam, religion is the motive spring of all actions in life. A Muslim of one country has far more sympathies with a Muslim living in another country than with a non-Muslim living in the same country ...

- ↑ "03323_Hicks.qxd" (PDF). Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ "Politics in Modern Science Fiction Syllabus". Ocf.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ Scott, Derek; Simpson, Anna-Louise (2008). Power and International Politics. Social Education Victoria.

- ↑ "U.S. Trade Policy — Economics". AEI. 15 February 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- 1 2 Official copy (free preview): "The Clash of Civilizations?". Foreign Affairs. Summer 1993.

- ↑ Sandra Fullerton Joireman (2003). Nationalism and Political Identity. London: Continuum. p. 30. ISBN 0-8264-6591-9.

- ↑ Carol Lansing and Edward D. English, eds. (2012). A Companion to the Medieval World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4.

External links

- From Paris to Cairo: Resistance of the Unacculturated on identity and the nation state.