Royal intermarriage

.jpg)

Royal intermarriage is the practice of members of ruling dynasties marrying into other reigning families. It was more commonly done in the past as part of strategic diplomacy for national interest. Although sometimes enforced by legal requirement on persons of royal birth, more often it has been a matter of political policy and/or tradition in monarchies.

In Europe, the practice was most prevalent from the medieval era until the outbreak of World War I, but evidence of intermarriage between royal dynasties in other parts of the world can be found as far back as the Late Bronze Age.[1] Monarchs were often in pursuit of national and international aggrandisement on behalf of themselves and their dynasties,[2] thus bonds of kinship tended to promote or restrain aggression.[3] Marriage between dynasties could serve to initiate, reinforce or guarantee peace between nations. Alternatively, kinship by marriage could secure an alliance between two dynasties which sought to reduce the sense of threat from or to initiate aggression against the realm of a third dynasty.[3] It could also enhance the prospect of territorial acquisition for a dynasty by procuring legal claim to a foreign throne, or portions of its realm (e.g., colonies), through inheritance from an heiress whenever a monarch failed to leave an undisputed male heir.

In parts of Europe, royalty continued to regularly marry into the families of their greatest vassals as late as the 16th century, thenceforth, tending to marry internationally. In other parts of the world royal intermarriage was less prevalent and the number of instances waxed and waned over time, depending on the culture and foreign policy of the era.

Royal marriage as international policy

While the contemporary Western ideal sees marriage as a unique bond between two people who are in love, families in which heredity is central to power or inheritance (such as royal families) have often seen marriage in a different light. There are often political or other non-romantic functions that must be served, and the relative wealth and power of the potential spouses may be considered. Marriage for political, economic, or diplomatic reasons, the marriage of state, was a pattern seen for centuries among European rulers.[4]

Africa

At times, marriage between members of the same dynasty has been common in Central Africa.[5]

In West Africa, the sons and daughters of Yoruba kings were traditionally given in marriage to their fellow royals as a matter of dynastic policy. Sometimes these marriages would involve members of other tribes. Erinwinde of Benin, for example, was taken as a wife by the Oba Oranyan of Oyo during his time as governor of Benin. Their son Eweka went on to give birth to the dynasty that rules the Kingdom of Benin today.

Marriages between the Swazi, Zulu and Thembu royal houses of southern Africa are common.[6] For example, the daughter of former South African president and Thembu royal Nelson Mandela, Zenani Mandela, in 1977 married Prince Thumbumuzi Dlamini, a brother of Mswati III, King of Swaziland.[7]

Examples of historical, mythical and contemporary royal intermarriages throughout Africa include:

- Mantfombi Dlamini, sister of Mswati III of Swaziland, and Goodwill Zwelithini, King of the Zulus, as his Great Royal Wife (1977)[8]

- The Toucouleur emperor Umar Tall and the daughter of the sultan Muhammed Bello of Sokoto[9]

Asia

Thailand

The Chakri Dynasty of Thailand has included marriages between royal relatives,[10] but marriages between dynasts and foreigners, including foreign royals, are rare. This is in part due to Section 11 of 1924 Palace Law of Succession which excludes members of the royal family from the line of succession if they marry a non-Thai national.[11]

The most recent king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is a first-cousin once removed of his wife, Sirikit, the two being, respectively, a grandson and a great-granddaughter of Chulalongkorn.[12] Chulalongkorn married a number of his half-sisters, including Savang Vadhana and Sunandha Kumariratana; all shared the same father, Mongkut.[13]

Vietnam

The Lý dynasty which ruled Dai Viet (Vietnam) married its princesses off to regional rivals to establish alliances with them. One of these marriages was between a Lý princess (Lý Chiêu Hoàng) and a member of the Chinese Trần (Chen) clan (Trần Thái Tông), which enabled the Trần to then topple the Lý and established their own Trần dynasty.[14][15]

A Lý princess also married into the Hồ family, which was also of Chinese origin and later established the Hồ dynasty which also took power after having a Tran princess marry one of their members, Hồ Quý Ly.[14][16]

Cambodia

The Cambodian King Chey Chettha II married the Vietnamese Nguyễn lord Princess Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Vạn, a daughter of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, in 1618.[17][18] In return, the king granted the Vietnamese the right to establish settlements in Mô Xoài (now Bà Rịa), in the region of Prey Nokor—which they colloquially referred to as Sài Gòn, and which later became Ho Chi Minh City.[19][20]

China

Marriage policy in imperial China differed from dynasty to dynasty. Several dynasties practiced Heqin, which involved marrying off princesses to other royal families.

The Xiongnu practiced marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side. The older sister of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of the Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected.[21][22][23][24] The Yenisei Kirghiz Khagans claimed descent from Li Ling.[25][26] Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli who also married a daughter of the Chanyu.[27]

The Xianbei Tuoba royal family of Northern Wei started to arrange for Han Chinese elites to marry daughters of the royal family in the 480s.[28] Some Han Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Han Chinese elites, the Han Chinese Liu Song royal Liu Hui 刘辉, married Princess Lanling 蘭陵公主 of the Northern Wei,[29][30] Princess Huayang 華陽公主 to Sima Fei 司馬朏, a descendant of Jin dynasty (265–420) royalty, Princess Jinan 濟南公主 to Lu Daoqian 盧道虔, Princess Nanyang 南阳长公主 to Xiao Baoyin 萧宝夤, a member of Southern Qi royalty.[31] Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to The Liang dynasty ruler Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong 蕭綜.[32]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended Northern Wei received the Jin prince Sima Chuzhi 司馬楚之 as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong 司馬金龍. Northern Liang King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[33]

The Rouran Khaganate arranged for one of their princesses, Khagan Yujiulü Anagui's daughter Princess Ruru 蠕蠕公主 to be married to the Han Chinese ruler Gao Huan of the Eastern Wei.[34][35]

The Kingdom of Gaochang was made out of Han Chinese colonists and ruled by the Han Chinese[36][37] Qu family which originated from Gansu.[38] Jincheng commandery 金城 (Lanzhou), district of Yuzhong 榆中 was the home of the Qu Jia.[39] The Qu family was linked by marriage alliances to the Turks, with a Turk being the grandmother of King Qu Boya.[40][41]

Tang dynasty (618–907) emperors gave princesses in marriage to rulers of the Uyghur Khaganate to consolidate the special trade and military relationship that developed after the Khaganate supported the Chinese during the An Lushan Rebellion.[42] At least three Tang imperial princesses are known to have married khagans between 758 and 821. These unions temporarily stopped in 788, which is believed in part to be because stability within the Chinese empire meant that they were politically unnecessary; however, threats from Tibet in the west, and a renewed need for Uyghur support, precipitated the marriage of Princess Taihe to Bilge Khagan.[42]

The ethnically Chinese Cao family ruling Guiyi Circuit established marriage alliances with the Uighurs of the Ganzhou Kingdom, with both the Cao rulers marrying Uighur princesses and with Cao princesses marrying Uighur rulers. The Ganzhou Uighur Khagan's daughter was married to Cao Yijin in 916.[43][44][45]

The Chinese Cao family ruling Guiyi Circuit established marriage alliances with the Saka Kingdom of Khotan, with both the Cao rulers marrying Khotanese princesses and with Cao princesses marrying Khotanese rulers. A Khotanese princess who was the daughter of the King of Khotan married Cao Yanlu.[46]

The Khitan Liao dynasty arranged for women from the Khitan royal consort Xiao clan to marry members of the Han Chinese Han 韓 clan, which originated in Jizhou 冀州 before being abducted by the Khitan and becoming part of the Han Chinese elite of the Liao.[47][48][49]

Han Chinese Geng family intermarried with the Khitan and the Han 韓 clan provided two of their women as wives to Geng Yanyi and the second one was the mother of Geng Zhixin.[50] Empress Rende's sister, a member of the Xiao clan, was the mother of Han Chinese General Geng Yanyi.[51]

Han Durang (Yelu Longyun) was the father of Queen dowager of State Chen, who was the wife of General Geng Yanyi and buried with him in his tomb in Zhaoyang in Liaoning.[52] His wife was also known as "Madame Han".[53] The Geng's tomb is located in Liaoning at Guyingzi in Chaoying.[54][55]

Emperors of the proceeding Song dynasty (960–1279) tended to marry from within their own borders. Tang emperors, mainly took their wives from high-ranking bureaucratic families, but the Song dynasty did not consider rank important when it came to selecting their consorts.[56] It has been estimated that only a quarter of Song consorts were from such families, with the rest being from lower status backgrounds. For example, Liu, consort of Emperor Zhenzong, had been a street performer and consort Miao, wife of Emperor Renzong was the daughter of his own wet nurse.[56]

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), emperors chose their consorts primarily from one of the eight Banner families, administrative divisions that divide all native Manchu families.[57] To maintain the ethnic purity of the ruling dynasty, after the Kangxi Period (1662–1722), emperors and princes were forbidden to marry non-Manchu wives.[58] Imperial daughters however were not covered by this ban, however, and as with their preceding dynasties, were often married to Mongol princes to gain political or military support, especially in the early years of the Qing dynasty; three of the nine daughters of Emperor Nurhaci and twelve of Emperor Hongtaiji's daughters were married to Mongol Princes.[58]

The Manchu Imperial Aisin Gioro clan practiced marriage alliances with Han Chinese Ming Generals and Mongol princes. Aisin Gioro women were married to Han Chinese Generals who defected to the Manchu side during the Manchu conquest of China. The Manchu leader Nurhaci married one of his granddaughters to the Ming General Li Yongfang 李永芳 after he surrendered Fushun in Liaoning to the Manchu in 1618 and a mass marriage of Han Chinese officers and officials to Manchu women numbering 1,000 couples was arranged by Prince Yoto 岳托 (Prince Keqin) and Hongtaiji in 1632 to promote harmony between the two ethnic groups.[59][60] Aisin Gioro women were married to the sons of the Han Chinese Generals Sun Sike (Sun Ssu-k'o) 孫思克, Geng Jimao (Keng Chi-mao), Shang Kexi (Shang K'o-hsi), and Wu Sangui (Wu San-kuei).[61]

Nurhaci's son Abatai's daughter was married to Li Yongfang.[62][63][64][65] The offspring of Li received the "Third Class Viscount" (三等子爵; sān děng zǐjué) title.[66] Li Yongfang was the great great great grandfather of Li Shiyao 李侍堯.[67][68]

The "Dolo efu" 和碩額駙 rank was given to husbands of Qing princesses. Geng Zhongming, a Han bannerman, was awarded the title of Prince Jingnan, and his son Geng Jingmao managed to have both his sons Geng Jingzhong and Geng Zhaozhong 耿昭忠 become court attendants under the Shunzhi Emperor and get married to Aisin Gioro women, with Prince Abatai's granddaughter marrying Geng Zhaozhong 耿昭忠 and Haoge's (a son of Hong Taiji) daughter marrying Geng Jingzhong.[69] A daughter 和硕柔嘉公主 of the Manchu Aisin Gioro Prince Yolo 岳樂 (Prince An) was wedded to Geng Juzhong 耿聚忠 who was another son of Geng Jingmao.[70]

The 4th daughter of Kangxi (和硕悫靖公主) was wedded to the son (孫承恩) of the Han Chinese Sun Sike (Sun Ssu-k'o) 孫思克.[71]

Japan and Korea

The Silla Kingdom had a practice that limited the succession to the throne to members of the seonggol, or "sacred bone", rank. To maintain their "sacred bone" rank, members of this caste often intermarried with one another in the same fashion that European royals intermarried to maintain a "pure" royal pedigree.[72]

After the Second Manchu invasion of Korea, Joseon Korea was forced to give several of their royal princesses as concubines to the Qing Manchu regent Prince Dorgon.[69][73][74][75][76][77][78] In 1650, Dorgon married the Korean Princess I-shun (義願).[79] The Princess' name in Korean was Uisun and she was Prince Yi Gaeyoon's (Geumnimgun) daughter.[80] Dorgon married two Korean princesses at Lianshan.[81]

The Japanese may not have seen intermarriage between them and the royal dynasties of the Korean Empire damaging to their prestige either.[82] According to the Shoku Nihongi, an imperially commissioned record of Japanese history completed in 797, Emperor Kanmu who ruled from 781 to 806 was the son of a Korean concubine, Takano no Niigasa, who was descended from King Muryeong of Baekje, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[82]

In 1920, Crown Prince Yi Un of Korea married Princess Masako of Nashimoto and, in May 1931, Yi Geon, grandson of Gojong of Korea, was married to Matsudaira Yosiko, a cousin of Princess Masako. The Japanese saw these marriages as a way to secure their colonial rule of Korea and introduce Japanese blood in to the Korean royal House of Yi.[82]

Europe

Medieval and Early Modern Europe

Careful selection of a spouse was important to maintain the royal status of a family: depending on the law of the land in question, if a prince or king was to marry a commoner who had no royal blood, even if the first-born was acknowledged as a son of a sovereign, he might not be able to claim any of the royal status of his father.[4]

Traditionally, many factors were important in arranging royal marriages. One such factor was the amount of territory that the other royal family governed or controlled.[4] Another, related factor was the stability of the control exerted over that territory: when there was territorial instability in a royal family, other royalty would be less inclined to marry into that family.[4] Another factor was political alliance: marriage was an important way to bind together royal families and their countries during peace and war and could justify many important political decisions.[4][83]

The increase in royal intermarriage often meant that lands passed into the hands of foreign houses, when the nearest heir was the son of a native dynast and a foreign royal.[84][n 1][n 2] The Habsburgs, for example, expanded their influence through arranged marriages and by gaining political privileges in what would become Switzerland, and in the 13th century the house aimed its marriage policy at families in Upper Alsace and Swabia.[85] Given the success of the Habsburgs' territorial acquisition-via-inheritance policy, a motto came to be associated with their dynasty: Bella gerant alii, tu, felix Austria, nube! ("Let others wage war. You, happy Austria, marry!")[86]

Monarchs sometimes went to great lengths to prevent this. On her marriage to Louis XIV of France, Maria Theresa, daughter of Philip IV of Spain, was forced to renounce her claim to the Spanish throne.[87] When monarchs or heirs apparent wed other monarchs or heirs, special agreements, sometimes in the form of treaties, were negotiated to determine inheritance rights. The marriage contract of Philip II of Spain and Mary I of England, for example, stipulated that the maternal possessions, as well as Burgundy and the Low Countries, were to pass to any future children of the couple, whereas the remaining paternal possessions (including Spain, Naples, Sicily, Milan) would first of all go to Philip's son Don Carlos, from his previous marriage to Maria Manuela of Portugal. If Carlos were to die without any descendants, only then would they pass to the children of his second marriage.[88] On the other hand, the Franco-Scottish treaty that arranged the 1558 marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots and Francis, the son and heir of Henry II of France, had it that if the queen died without descendants, Scotland would fall to the throne of France.[88]

Religion has always been closely tied to European political affairs, and as such it played an important role during marriage negotiations. The 1572 wedding in Paris of the French princess Margaret of Valois to the leader of France's Huguenots, Henry III of Navarre, was ostensibly arranged to effect a rapprochement between the nation's Catholics and Protestants, but proved a ruse for the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.[89] After the English Reformation, matches between English monarchs and Roman Catholic princesses were often unpopular, especially so when the prospective queen consort was unwilling to convert, or at least practice her faith discreetly.[n 3] Passage of the Act of Settlement 1701 disinherited any heir to the throne who married a Catholic.[91] Other ruling houses, such as the Romanovs[n 4] and Habsburgs,[94] have at times also insisted on dynastic marriages only being contracted with people of a certain faith or those willing to convert. When in 1926 Astrid of Sweden married Leopold III of Belgium, it was agreed that her children would be raised as Catholics but she was not required to give up Lutheranism, although she chose to convert in 1930.[95] Some potential matches were abandoned due to irreconcilable religious differences. For example, plans for the marriage of the Catholic Władysław IV Vasa and the Lutheran Elisabeth of Bohemia, Princess Palatine proved unpopular with Poland's largely Catholic nobility and were quietly dropped.[96]

Marriages among ruling dynasties and their subjects have at times been common, with the marriages such as that of Edward the Confessor, King of England with Edith of Wessex and Władysław II Jagiełło, King of Poland with Elizabeth Granowska being far from unheard of in medieval Europe. However, as dynasties approached absolutism and sought to preserve loyalty among competing members of the nobility, most eventually distanced themselves from kinship ties to local nobles by marrying abroad.[97][98] Marriages with subjects brought the king back down to the level of those he ruled, often stimulating the ambition of his consort's family and evoking jealousy—or disdain—from the nobility. The notion that monarchs should marry into the dynasties of other monarchs to end or prevent war was, at first, a policy driven by pragmatism. During the era of absolutism, this practice contributed to the notion that it was socially, as well as politically, disadvantageous for members of ruling families to intermarry with their subjects and pass over the opportunity for marriage into a foreign dynasty.[99][100]

Ancient Rome

While Roman emperors almost always married wives who were also Roman citizens, the ruling families of the empire's client kingdoms in the Near East and North Africa often contracted marriages with other royal houses to consolidate their position.[101] These marriages were often contracted with the approval, or even at the behest, of the Roman emperors themselves. Rome thought that such marriages promoted stability among their client states and prevented petty local wars that would disturb the Pax Romana.[102] Glaphyra of Cappadocia was known to have contracted three such royal intermarriages: with Juba II&I, King of Numidia and Mauretania, Alexander of Judea and Herod Archelaus, Ethnarch of Samaria.[103]

Other examples from the Ancient Roman era include:

- Polemon II, King of Pontus and Berenice of Judea[104]

- Aristobulus IV of Judea and Berenice of Judea[105]

- Aristobulus Minor of Judea and Iotapa of Emesa[106]

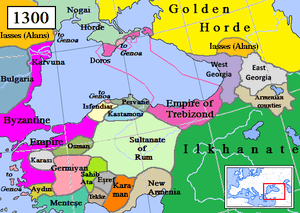

Byzantine Empire

Though some emperors, such as Justin I and Justinian I, took low-born wives,[n 5] dynastic intermarriages in imperial families were not unusual in the Byzantine Empire. Following the fall of Constantinople in 1204, the ruling families, the Laskarides and then the Palaiologoi, thought it prudent to marry into foreign dynasties. One early example is the marriage of John Doukas Vatatzes with Constance, the daughter of Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire to seal their alliance.[109] After establishing an alliance with the Mongols in 1263, Michael VIII Palaiologos married two of his daughters to Mongol khans to cement their agreement: his daughter Euphrosyne Palaiologina was married to Nogai Khan of the Golden Horde, and his daughter Maria Palaiologina, was married to Abaqa Khan of the Ilkhanate.[110] Later in the century, Andronikos II Palaiologos agreed martial alliances with Ghazan of the Ilkhanate and Toqta and Uzbeg of the Golden Horde, which were quickly followed by weddings with his daughters.[111]

The Grand Komnenoi of the Empire of Trebizond were famed for marrying their daughters to their neighbours as acts of diplomacy.[n 6] Theodora Megale Komnene, daughter of John IV, was married to Uzun Hassan, lord of the Aq Qoyunlu, to seal an alliance between the Empire and the so-called White Sheep. Although the alliance failed to save Trebizond from its eventual defeat, and despite being a devout Christian in a Muslim state, Theodora did manage to exercise a pervasive influence both in the domestic and foreign actions of her husband.[113]

Though usually made to strengthen the position of the empire, there are examples of interdynastic marriages destabilising the emperor's authority. When Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos married his second wife, Eirene of Montferrat, in 1284 she caused a division in the Empire over her demand that her own sons share in imperial territory with, Michael, his son from his first marriage. She resorted to leaving Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and setting up her own court in the second city of the Empire, Thessalonica.[109]

Post World War I era

In modern times, among European royalty at least, marriages between royal dynasties have become much rarer than they once were. Members of Europe's dynasties increasingly married members of the titled nobility, including George VI of the United Kingdom, Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood, Prince Michael of Kent, Charles, Prince of Wales, Baudouin of Belgium, Albert II of Belgium, Prince Amedeo of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este, Franz Joseph II, Prince of Liechtenstein, Hans-Adam II of Liechtenstein, Prince Constantin of Liechtenstein, Princess Nora of Liechtenstein, Princess Désirée, Baroness Silfverschiöld, Infanta Pilar, Duchess of Badajoz, Infanta Elena, Duchess of Lugo and Guillaume, Hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg or untitled nobility as Philippe of Belgium and Beatrix of the Netherlands, and very often commoners, as Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden, Harald V of Norway, Haakon, Crown Prince of Norway, Henri of Luxembourg, Felipe VI of Spain, Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands, Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark, Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Albert II of Monaco have done.

In Europe, among current reigning and former monarchs and heirs of ruling families, only Juan Carlos I of Spain, Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein married members of a foreign dynasty.[n 7][114]

Members of two reigning houses

Royal intermarriage still occurs. For example:

- Prince Nikolaus of Liechtenstein and Princess Margaretha of Luxembourg[115] (1982, most recent example of intermarriage between two European dynasties reigning at the time of the wedding)

- Constantine II of Greece and Princess Anne Marie of Denmark (1964)[116]

- Jean, Grand Duke of Luxembourg and Princess Joséphine Charlotte of Belgium (1953)[117]

- Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and Philip Mountbatten (born a Prince of Greece and Denmark) (1947)[118]

- Peter II of Yugoslavia and Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark (1944)[119]

- Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta and Princess Irene of Greece (1939)

- Frederick IX of Denmark and Princess Ingrid of Sweden (1935)[120]

- Prince George, Duke of Kent and Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark (1934)[121]

- Umberto II of Italy and Princess Marie José of Belgium (1930)[122]

- Boris III of Bulgaria and Princess Giovanna of Italy (1930)[123]

- Olav V of Norway and Princess Märtha of Sweden (1929)[124]

- Leopold III of Belgium and Princess Astrid of Sweden (1926)[125]

- Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden and Lady Louise Mountbatten (born as Princess Louise of Battenberg) (1923)[126]

- Prince Paul of Yugoslavia and Princess Olga of Greece and Denmark (1923)

- Alexander I of Yugoslavia and Princess Maria of Romania (1922)[115][127]

- George II of Greece and Princess Elisabeth of Romania (1921)

- Carol II of Romania and Princess Helen of Greece (1921)

- Prince Axel of Denmark and Princess Margaretha of Sweden (1919)

Members of one reigning house and one non-reigning house

- Princess Caroline of Monaco and Ernst August, Prince of Hanover (1999)[128]

- Princess Doña María of Bourbon-Two Sicilies and Archduke Simeon of Austria (1996)[129]

- Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein and Duchess Sophie in Bavaria (1993)[114]

- Prince Gundakar of Liechtenstein and Princess Marie d'Orléans (1989)

- Princess Astrid of Belgium and Archduke Lorenz of Austria-Este (1984)[130]

- Princess Marie-Astrid of Luxembourg and Archduke Carl Christian of Austria (1982)[131]

- Princess Barbara of Liechtenstein and Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia (1973) [132]

- Princess Benedikte of Denmark and Richard, 6th Prince of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (1968) [133]

- Princess Irene of the Netherlands and Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma (1964)[134]

- Princess Sophia of Greece and Denmark and Juan Carlos I of Spain (1962)[135]

- Princess Birgitta of Sweden and Prince Johann Georg of Hohenzollern (1961)[136]

- Princess Alix of Luxembourg and Antoine, 13th Prince de Ligne (1950) [137]

- Prince Karl Alfred of Liechtenstein and Archduchess Agnes Christina of Austria (1949)

- Prince Heinrich of Liechtenstein and Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria (1949)

- Prince Georg Hartmann of Liechtenstein and Duchess Maria Christina of Württemberg (1948)

- Princess Sophie of Greece and Denmark and Prince George William of Hanover (1946)

- Princess Maria Francesca of Savoy and Prince Luigi of Bourbon-Parma (1939)

- Paul, King of the Hellenes and Princess Frederica of Hanover (1938)

- Prince Eugenio, Duke of Genoa and Princess Lucia of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (1938)

- Princess Feodora of Denmark and Prince Christian of Schaumburg-Lippe (1937)

- Juliana of the Netherlands and Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld (1936)

- Prince Gustaf Adolf of Sweden, Duke of Västerbotten and Princess Sibylla of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1932)

- Princess Theodora of Greece and Denmark and Berthold, Margrave of Baden (1931)

- Princess Cecilie of Greece and Denmark and Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse (1931)

- Princess Ileana of Romania and Archduke Anton of Austria (1931)

- Princess Hilda of Luxembourg and Adolf, 10th Prince of Schwarzenberg (1930)

- Princess Margarita of Greece and Denmark and Gottfried, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1930)

- Princess Sophie of Greece and Denmark and Prince Christoph of Hesse (1930)

- Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark and Princess Françoise d'Orléans (1929)

- Prince Filiberto, Duke of Genoa and Princess Lydia d'Arenberg (1928)

- Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta and Princess Anne d'Orléans (1927)

- Princess Mafalda of Savoy and Philipp, Landgrave of Hesse (1925)

- Princess Nadezhda of Bulgaria and Duke Albrecht Eugen of Württemberg (1924)

- Princess Elisabeth of Luxembourg and Prince Ludwig Philipp of Thurn and Taxis (1922)

- Princess Margaret of Denmark and Prince René of Bourbon-Parma (1921)

- Princess Antonia of Luxembourg and Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (1921)

- Princess Sophie of Luxembourg and Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony (1921)

- Princess Maria Bona of Savoy-Genoa and Prince Konrad of Bavaria (1921)

- Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg and Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma (1919)

Modern examples of dynastic intra-marriage

As a result of dynastic intra-marriage all of Europe's 10 currently reigning hereditary monarchs since 1939 descend from a common ancestor, Johan Willem Friso, Prince of Orange.[139]

| Title | Monarch | Country | Cousin | Removed | Most Recent Common Ancestor | Death of MRCA | Gen. from JWF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen | Elizabeth II | United Kingdom | --- | ---- | ------ | ------ | 9 |

| King | Harald V | Norway | 2nd | none | Edward VII of the United Kingdom | 6-May-1910 | 10 |

| Queen | Margrethe II | Denmark | 3rd | none | Christian IX of Denmark | 29-Jan-1906 | 10 |

| King | Carl XVI Gustaf | Sweden | 3rd | none | Queen Victoria | 22-Jan-1901 | 10 |

| King | Felipe VI | Spain | 3rd | once | Queen Victoria | 22-Jan-1901 | 11 |

| King | Albert II | Belgium | 3rd | none | Christian IX of Denmark | 29-Jan-1906 | 10 |

| Grand Duke | Henri | Luxembourg | 3rd | once | Christian IX of Denmark | 29-Jan-1906 | 10 |

| King | Willem-Alexander | Netherlands | 5th | once | Frederick II Eugene, Duke of Württemberg | 25-Dec-1797 | 10 |

| Prince | Hans-Adam II | Liechtenstein | 7th | once | John William Friso, Prince of Orange | 14-Jul-1711 | 10 |

| Prince | Albert II | Monaco | 7th | twice | John William Friso, Prince of Orange | 14-Jul-1711 | 11 |

Muslim World

Al-Andalus

From the time of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania and throughout the Reconquista, marriage between Spanish and Umayyad royals was not uncommon. Early marriages, such as that of Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa and Egilona at the turn of the 8th century, was thought to help establish the legitimacy of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula.[140] Later instances of intermarriage were often made to seal trade treaties between Christian kings and Muslim caliphs.[141]

Ottoman Empire

The marriages of Ottoman sultans and their sons in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries tended to be with members of the ruling dynasties of neighbouring powers.[142] With little regard for religion, the sultans contracted marriages with both Christians and Muslims; the purpose of these royal intermarriages were purely tactical. The Christian Byzantines and Serbians, as well as the Muslim beyliks of Germiyan, Saruhan, Karaman and Dulkadir were all potential enemies and marriage was seen as a way of securing alliances with them.[142] Marriage with foreign dynasties seems to have ceased in 1504, with the last marriage of a sultan to a foreign princess being that of Murad II and Mara Branković, daughter of the Serbian ruler Đurađ Branković, in 1435. By this time, the Ottomans had consolidated their power in the area and absorbed or subjugated many of their former rivals, and so marriage alliances were no longer seen as important to their foreign policy.[142]

The Islamic principle of kafa'a discourages the marriages of women to men of differing religion or of inferior status.[n 9] Neighbouring Muslim powers did not start to give their daughters in marriage to Ottoman princes until the fifteenth century, when they were seen to have grown in importance. This same principle meant that, while Ottoman men were free to marry Christian women, Muslim princesses were prevented from marrying Christian princes.[144]

Post World War I era

There are several modern instances of intermarriage between members of the royal families and former royal families of Islamic states (i.e., Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, the constituent states of the United Arab Emirates, etc.).

Examples include:

- Muhammad Ali, Prince of the Sa'id, son of Fuad II of Egypt and Princess Noal Zaher Shah, granddaughter Zahir Shah of Afghanistan (2013)[145]

- Sheik Khalid bin Hamad Al Khalifa, son of Hamad Al Khalifa, King of Bahrain and Princess Sahab bint Abdullah, daughter of Abdullah, King of Saudi Arabia (2011)[146]

- Sheik Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, half-brother of Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Emir of Abu Dhabi and President of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Sheika Manal bint Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, daughter of Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of UAE (2005)

- Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum of Dubai and Princess Haya bint Hussein of Jordan (2004)[147]

- Ibrahim Ismail, Sultan of Johor and Raja Zarith Sofia of Perak (1982)[148]

- Muhammad Abdel Moneim and Fatma Neslişah (1940)

- Mohammed Reza Pahlavi of Iran and Princess Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (1939–1948)[144]

- Senije Zogu, sister of Zogu I of Albania, and Mehmet Abid, son of Abdul Hamid II.

- Princess Durru Shehvar, daughter of Ottoman Emperor Abdülmecid II, and Azam Jah, son of Nizam of Hyderabad Asaf Jah VII (1931) [149]

Morganatic marriage

At one time, some dynasties adhered strictly to the concept of royal intermarriage. The Bernadottes, Habsburgs, Sicilian and Spanish Bourbons and Romanovs, among others, introduced house laws which governed dynastic marriages;[150] it was considered important that dynasts marry social equals (i.e., other royalty), thereby ruling out even the highest-born non-royal nobles.[151] Those dynasts who contracted undesirable marriages often did so morganatically. Generally, this is a marriage between a man of high birth and a woman of lesser status (such as a daughter of a low-ranked noble family or a commoner).[152] Usually, neither the bride nor any children of the marriage has a claim on the bridegroom's succession rights, titles, precedence, or entailed property. The children are considered legitimate for all other purposes and the prohibition against bigamy applies.[153]

Examples of morganatic marriages include:

- Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine and Countess Julia Hauke (1851)[154]

- Duke Alexander of Württemberg and Countess Claudine Rhédey von Kis-Rhéde (1835)[155]

- Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich and Countess Joanna Grudna-Grudzińska (1796)[156]

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Countess Sophie Chotek von Chotkova und Wognin (1900)[157]

Inbreeding

Over time, because of the relatively limited number of potential consorts, the gene pool of many ruling families grew progressively smaller, until all European royalty was related. This also resulted in many being descended from a certain person through many lines of descent, such as the numerous European royalty and nobility descended from Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom or King Christian IX of Denmark.[158] The House of Habsburg was infamous for inbreeding, with the Habsburg lip cited as an ill effect, although no genetic evidence has proved the allegation. The closely related houses of Habsburg, Bourbon, Braganza and Wittelsbach[n 10] also engaged in first-cousin unions frequently and in double-cousin and uncle-niece marriages occasionally.[159][160]

Examples of incestuous marriages and the impact of inbreeding on royal families include:

- All rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty from Ptolemy II were married to their brothers and sisters, so as to keep the Ptolemaic blood "pure" and to strengthen the line of succession. Cleopatra VII (also called Cleopatra VI) and Ptolemy XIII, who married and became co-rulers of ancient Egypt following their father's death, are the most widely known example.[161]

- Jean V of Armagnac was said to have formed a rare brother-sister liaison,[162] left descendants and claimed to be married. There is no evidence that this "marriage" was contracted for dynastic rather than personal reasons.[162]

- One of the most famous examples of a genetic trait aggravated by royal family intermarriage was the House of Habsburg, which inmarried particularly often and is known for the mandibular prognathism of the Habsburger (Unter) Lippe (otherwise known as the 'Habsburg jaw', 'Habsburg lip' or 'Austrian lip'"). This was typical for many Habsburg relatives over a period of six centuries.[163]

See also

Notes

- ↑ George I inherited the throne of Great Britain through his mother, Sophia of Hanover, a female line descendant of James VI and I.

- ↑ The crowns of the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile came under Habsburg rule when they were inherited by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, son of Joanna, Queen of Castile and Aragon and Philip the Handsome, son of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.[84]

- ↑ A prime example is the marriage of the Catholic Henrietta Maria and Charles I of England. Her open practice of her faith and insistence on maintaining a Catholic retinue during a time of religious intolerance in English society eventually made her a deeply unpopular queen with the general public.[90]

- ↑ Russian dynasts often only married foreign princesses when they converted to Russian Orthodoxy.[92] For example, Alix of Hesse, wife of Nicholas II, converted from her native Lutheranism.[93]

- ↑ Justin I's wife, Euphemia, was reported to be both a slave and a barbarian,[107] and Justinian II's wife, Theodora, was an actor and, some claim, a prostitute.[108]

- ↑ Donald MacGillivray Nicol says in The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261–1453: "The daughters of Alexios II Grand Komnenos married the emirs of Sinope and of Erzindjan, his granddaughters married the emir of Chalybia and the Turkoman chieftain of the so-called Ak-Koyunlu, or horde of the White Sheep; his great-granddaughters, the children of Alexios III, who died in 1390, performed even greater service to the Empire."[112]

- ↑ Both Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and Juan Carlos I of Spain have married members of the Greek royal family, Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark and Princess Sophia of Greece and Denmark respectively. In 1993, Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein married Duchess Sophie in Bavaria, a member of the House of Wittelsbach.[114] Both the Greek royal dynasty, the House of Glücksburg, and the House of Wittelsbach have been deposed.

- ↑ Knud, Hereditary Prince of Denmark and Princess Caroline-Mathilde of Denmark, married in 1933, were first cousins and members of the House of Glücksburg, as male-line grandchildren of Frederick VIII of Denmark.[138]

- ↑ Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban explains in her article Islamic Law and Society in the Sudan that "It is preferable that a non-Muslim convert to Islam before marriage to a Muslim man, however, it is not essential - it is essential that a non-Muslim man convert to Islam before contemplating marriage with a Muslim woman"[143]

- ↑ The Wittlesbach line suffered from several cases of mental illness, often attributed to their frequent intermarriages. Several family members suffered from mental and physical illnesses, as well as epilepsy[159]

References and Sources

References

- ↑ Cohen, p.165

- ↑ Thomson, pp.79–80

- 1 2 Bucholz, p.228

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fleming

- ↑ Dobbs, David

- ↑ 'Wedding Brings Xhosa, Zulu Tribes Together', LA Times

- ↑ Keller

- ↑ 'Nelson Mandela: A Unique World Leader Dies At 95', Nigerian Echo

- ↑ Kobo, p.46

- ↑ Dobbs

- ↑ Liu & Perry

- ↑ Thailand Country Study

- ↑ Stengs, p.275

- 1 2 Kenneth R. Hall (2008). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400-1800. Lexington Books. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-7391-2835-0. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ Ainslie Thomas Embree; Robin Jeanne Lewis (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 190. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ K. W. Taylor (9 May 2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- ↑ Mai Thục, Vương miện lưu đày: truyện lịch sử, Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa - thông tin, 2004, p.580; Giáo sư Hoàng Xuân Việt, Nguyễn Minh Tiến hiệu đính, Tìm hiểu lịch sử chữ quốc ngữ, Ho Chi Minh City, Công ty Văn hóa Hương Trang, pp.31-33; Helen Jarvis, Cambodia, Clio Press, 1997, p.xxiii.

- ↑ Nghia M. Vo; Chat V. Dang; Hien V. Ho (2008-08-29). The Women of Vietnam. Saigon Arts, Culture & Education Institute Forum. Outskirts Press. ISBN 1-4327-2208-5.

- ↑ Henry Kamm (1998). Cambodia: report from a stricken land. Arcade Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 1-55970-433-0.

- ↑ "Nguyễn Bặc and the Nguyễn". Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ↑ , p. 31.

- ↑ Qian Sima; Burton Watson (January 1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han dynasty. Renditions-Columbia University Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-231-08166-5.

- ↑ Monumenta Serica. H. Vetch. 2004. p. 81.

- ↑ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ↑ Veronika Veit, ed. (2007). The role of women in the Altaic world: Permanent International Altaistic Conference, 44th meeting, Walberberg, 26-31 August 2001. Volume 152 of Asiatische Forschungen (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 61. ISBN 3447055375. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Michael Robert Drompp (2005). Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history. Volume 13 of Brill's Inner Asian library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 9004141294. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Lin Jianming (林剑鸣) (1992). 秦漢史 [History of Qin and Han]. Wunan Publishing. pp. 557–8. ISBN 978-957-11-0574-1.

- ↑ Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- ↑ Wendy Swartz; Robert Campany; Yang Lu; Jessey Choo (21 May 2013). Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook. Columbia University Press. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-0-231-15987-6. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Papers on Far Eastern History. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. p. 86.

- ↑ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

- ↑ Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. 22 September 2014. pp. 1566–. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- ↑ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

- ↑ Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. 2007. pp. 316–. ISBN 978-0-7656-4182-3.

- ↑ Gao Huan, as demanded by Yujiulü Anagui as one of the peace terms between Eastern Wei and Rouran, married the Princess Ruru in 545, and had her take the place of Princess Lou as his wife, but never formally divorced Princess Lou. After Gao Huan's death, pursuant to Rouran customs, the Princess Ruru became married to Gao Huan's son Gao Cheng, who also, however, did not formally divorce his wife.

- ↑ Baij Nath Puri (1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ↑ Charles Eliot; Sir Charles Eliot (1998). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Psychology Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0679-2.

- ↑ Marc S. Abramson (31 December 2011). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 0-8122-0101-9.

- ↑ Roy Andrew Miller (1959). Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty [Chou Shu 50. 10b-17b]: Translated and Annotated by Roy Andrew Miller. University of California Press. pp. 5–. GGKEY:SXHP29BAXQY.

- ↑ Jonathan Karam Skaff (1998). Straddling steppe and town: Tang China's relations with the nomads of inner Asia (640-756). University of Michigan. p. 57.

- ↑ Asia Major. Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. 1998. p. 87.

- 1 2 Veit, p.57

- ↑ Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang. BRILL. 7 June 2013. pp. 44–. ISBN 90-04-25233-9.

- ↑ Lilla Russell-Smith (2005). Uygur Patronage In Dunhuang: Regional Art Centres On The Northern Silk Road In The Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. BRILL. pp. 63–. ISBN 90-04-14241-X.

- ↑ Wenjie Duan; Chung Tan (1 January 1994). Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie. Abhinav Publications. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-81-7017-313-7.

- ↑ Lilla Russell-Smith (2005). Uygur Patronage In Dunhuang: Regional Art Centres On The Northern Silk Road In The Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. BRILL. pp. 23–. ISBN 90-04-14241-X.

- ↑ Biran 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ Biran 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ Cha 2005, p. 51.

- ↑ Yang, Shao-yun (2014). "Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200". In Fiaschetti, Francesca; Schneider, Julia. Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 22.

- ↑ Orient. Maruzen Company. 2004. p. 41.

- ↑ Orient. Maruzen Company. 2004. p. 41.

- ↑ Hsueh-man Shen; Asia Society; Asia Society. Museum; Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (Berlin, Germany), Museum Rietberg (1 September 2006). Gilded splendor: treasures of China's Liao Empire (907-1125). 5 continents. p. 106. ISBN 978-88-7439-332-9. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Jiayao An (1987). Early Chinese Glassware. Millennia. p. 12.

- ↑ http://kt82.zhaoxinpeng.com/view/138019.htm http://www.academia.edu/4954295/La_Steppe_et_l_Empire_la_formation_de_la_dynastie_Khitan_Liao_

- 1 2 Zhao, p.34

- ↑ Walthall, p.138

- 1 2 Walthall, p.149

- ↑ Anne Walthall (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. University of California Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-520-25444-2.

- ↑ Frederic Wakeman (1 January 1977). Fall of Imperial China. Simon and Schuster. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-02-933680-9.

- ↑ Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- ↑ http://www.lishiquwen.com/news/7356.html

- ↑ http://www.fs7000.com/wap/?9179.html

- ↑ http://www.75800.com.cn/lx2/pAjRqK/9N6KahmKbgWLa1mRb1iyc_.html

- ↑ https://read01.com/aP055D.html

- ↑ Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/LI_SHIH-YAO.html

- ↑ http://12103081.wenhua.danyy.com/library1210shtml30810106630060.html

- 1 2 FREDERIC WAKEMAN JR. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 1017–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ↑ FREDERIC WAKEMAN JR. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 1018–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ↑ Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- ↑ Kim, p.56

- ↑ Frank W. Thackeray; John E. Findling (31 May 2012). Events That Formed the Modern World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-59884-901-1. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ Arthur W. Hummel (1991). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing period: 1644-1912. SMC publ. p. 217. ISBN 978-957-638-066-2. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ Library of Congress. Orientalia Division (1943). 清代名人傳略: 1644-1912. 經文書局. p. 217. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ Raymond Stanley Dawson (1972). Imperial China. Hutchinson. p. 275. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ Raymond Stanley Dawson (1976). Imperial China. Penguin. p. 306.

- ↑ DORGON

- ↑ 梨大史苑. 梨大史學會. 1968. p. 105. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - ↑ http://www.gachonherald.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=32

- ↑ Li Ling (1995). Son of Heaven. Chinese Literature Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-7-5071-0288-8. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - 1 2 3 Kowner, p.478

- ↑ Beeche (2009), p.1

- 1 2 'Charles V', Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Heimann, pp.38–45

- ↑ Christakes, p.437

- ↑ Maland, p.227

- 1 2 Verzijl, p.301

- ↑ anselme, p.145

- ↑ Griffey, p.3

- ↑ BAILII, 'Act of Settlement 1700'

- ↑ Mandelstam Balzer, p.56

- ↑ Rushton, p.12

- ↑ Curtis, p.271

- ↑ Beéche, p.257

- ↑ Czaplinski, pp.205-208

- ↑ Durant, pp.552–553, 564–566, 569, 571, 573, 576

- ↑ Prazmowska, p.56

- ↑ Beeche (2010), p.24

- ↑ Greenfeld, p.110

- ↑ Warwick, p.36

- ↑ Salisbury, p.137

- ↑ Roller, p.251

- ↑ Schürer, Millar & Fergus. p.474

- ↑ Morgan Gilman, p.1

- ↑ William, p.301

- ↑ Garland, p.14

- ↑ Frassetto, p.332

- 1 2 Ostrogorsky, p.441

- ↑ Nicol, p.304

- ↑ Jackson, p.203

- ↑ Nicol, p.403

- ↑ Bryer, p.146

- 1 2 3 Beeche (2009), p.13

- 1 2 deBadts de Cugnac, pp.680–681

- ↑ 'Queen Anna Maria', The Greek Monarchy

- ↑ 'Life Goes to a Twice Royal Wedding: Luxembourg Prince Marries a Princess', Life

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.514–515, 532

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.534, 873

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.354

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.509, 529

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.620

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.333

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.710

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.290

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.845

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.870"

- ↑ 'Andrea Casiraghi, second in line to Monaco's throne, weds Colombian heiress', The Telegraph

- ↑ Verlag, p.105

- ↑ 'Princess Astrid', The Belgian Monarchy

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.195, 680–681

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.641, 876

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.335

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, pp.590–591, 730

- ↑ 'End of a Royal romance? Spain's King and Queen to shun Golden Wedding celebration sparking rumours the pair are 'estranged, The Daily Mail

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.849

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.678

- ↑ Thomas, p.91

- ↑ "Roglo Genealogical database".

- ↑ Schaus, p.593

- ↑ Albany & Salhab, pp.70–71

- 1 2 3 Peirce, pp.30–31

- ↑ Fluehr-Lobban

- 1 2 Magill, p.2566

- ↑ 'Prince Muhammed Ali of Egypt and Princess Noal Zaher of Afghanistan Prepare for their Royal Wedding', Hello!

- ↑ "Shaikh Khalid bin Hamad marries daughter of Saudi Monarch". Bahrain News Agency. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ 'Biographies: HRH Princess Haya',Office of HRH Princess Haya Bint Al Hussein

- ↑ 'Tribute to mothers’ caring nature', The Star

- ↑ Sarma, 'Bella Vista'

- ↑ deBadts de Cugnac, p.833, 173–175, 368, 545, 780–782

- ↑ Beeche (2010), p.vi-x

- ↑ Diesbach, pp.25–26

- ↑ Diesbach, p.35

- ↑ Thornton, p.162

- ↑ Vork, p.13

- ↑ Wortman, p.123

- ↑ Cecil, p.14

- ↑ Beeche (2009), p.7

- 1 2 Owens, p.41

- ↑ Ruiz, p.47

- ↑ Bevan

- 1 2 Guyenne, p.45

- ↑ 'Topics in the History of Genetics and Molecular Biology: The Habsburg Lip', Michigan State University

Sources

- Albany, HRH Prince Michael of; Salhab, Walid Amine (2006). The Knights Templar of the Middle East (1st ed.). MA, USA: Weister Books. ISBN 9781578633463.

- Alexander, Harriet (31 August 2013). "Andrea Casiraghi, second in line to Monaco's throne, weds Colombian heiress". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Anselme, Père (1967). Histoire de la Maison Royale de France (in French). I. Paris: Editions du Palais-Royal. p. 145.

- deBadts de Cugnac, Chantal; Coutant de Saisseval, Guy (2002). Le Petit Gotha [The Little Gotha] (in French). Paris, France: Nouvelle Imprimerie Laballery. ISBN 2950797431.

- "Act of Settlement 1700". BAILII. n.d. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. New York, USA: Routledge. ISBN 9780415243575.

- Beeche, Arturo (2009). The Gotha: Still a Continental Royal Family, Vol. 1. Richmond, US: Kensington House Books. ISBN 9780977196173.

- Beeche, Arturo (2013). The Coburgs of Europe. Richmond, US: Eurohistory. ISBN 9780985460334.

- Beeche, Arturo (2010). The Grand Dukes. Berkeley, CA, US. ISBN 9780977196180.

- Bevan, E.R. "House of Ptolomey, The". uchicago.edu.

- "Biographies: HRH Princess Haya". Office of HRH Princess Haya Bint Al Hussein. n.d. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Bryer, Anthony (1975). "Greeks and Türkmens: The Pontic Exception". Dumbarton Oak Papers. 29: 113–148. doi:10.2307/1291371. JSTOR 1291371.

- Bucholz, Robert; Key, Newton (2009). Early Modern England 1485–1714: A Narrative History. Oxford. ISBN 9781405162753.

- Cecil, Lamar (1996). Wilhelm II: Emperor and exile, 1900–1941. North Carolina, US: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807822838.

- de Ferdinandy, Michael (n.d.). "Charles V". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Christakes, George (2010). Integrative Problem-Solving in a Time of Decadence. Springer. p. 437. ISBN 9789048198894. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- Cohen, Raymond; Vestbrook, Raymond (2000). Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations. Baltimore. ISBN 9780801861994.

- Curtis, Benjamin (2013). The Habsburgs: The History of a Dynasty. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781441150028.

- Czaplinski, Władysław (1976). Władysław IV i jego czasy [Władysław IV and His Times] (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland: Wiedza Poweszechna.

- Diesbach, Ghislain (1967). Secrets of the Gotha: Private Lives of Royal Families of Europe. London, UK: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 9783928741200.

- Dobbs, David (2011). "The Risks and Rewards of Royal Incest". National Geographic Magazine. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- Durant, Will (1950). The Story of Civilzation: The Age of Faith. IV. New York, USA: Simone and Schuster. ISBN 9781451647617.

- "End of a Royal romance? Spain's King and Queen to shun Golden Wedding celebration sparking rumours the pair are 'estranged'". The Daily Mail. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Fleming, Patricia H. (1973). "The Politics of Marriage Among Non-Catholic European Royalty". Current Anthropology. 14 (3): 231. doi:10.1086/201323.

- Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (1987). "Islamic Law and Society in the Sudan". 26 (3 ed.). Islamabad, Pakistan: Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. California, US: ABC-CLIO Ltd. ISBN 9781576072639.

- Garland, Lynda (2002). Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527–1204. Oxford, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9781134756391.

- Guyenne, Valois (2001). Incest and the Medieval Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780861932269.

- Greenfeld, Liah (1993). Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674603196.

- Griffey, Erin (2008). Henrietta Maria: piety, politics and patronage. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754664208.

- Haag, Michael (2003). The Rough Guide History of Egypty. London, UK: Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 9781858289403. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- Heimann, Heinz-Dieter (2010). Die Habsburger: Dynastie und Kaiserreiche [The Habsburgs: dynasty and empire] (in German). ISBN 9783406447549.

- Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the West, 1221-1410. Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman. ISBN 0582368960.

- Keller, Bill (1990). "Zulu King Breaks Ties To Buthelezi". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- Kelly, Edmond (1991). Revolutionary Ethiopia: From Empire to People's Republic. Bloomington, US: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253206466.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. University of Indiana Press. ISBN 9780253000248.

- Kobo, Ousman (2012). Unveiling Modernity in Twentieth-Century West African Islamic Reforms. Leiden, Netherlands: Kononklijke Brill. ISBN 9789004233133.

- Kowner, Rotem (2012). Race and Racism in Modern East Asia: Western and Eastern Constructions. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004237292.

- Liu, Caitlin; Perry, Tony (2004). "Thais Saddened by the Death of Young Prince". LA Times. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Life Goes to a Twice Royal Wedding: Luxembourg Prince Marries a Princess". Life. 1953.

- Macurdy, Grace H.; Forrer, Leonard (1993). Two Studies on Women in Antiquity. Illinois, US: Ares Publishers. ISBN 9780890055434.

- Magill, Frank (2014). The 20th Century: Dictionary of World Biography. 8. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9781317740605.

- Maland, David (1991). Europe in the Seventeenth Century (Second ed.). London, UK: Macmillan. ISBN 0333335740.

- Mandelstam Balzer, Marjorie (2010). Religion and Politics in Russia. New York, US: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 9780765624147.

- Morgan Gilman, Florence (2003). Herodias: At Home in that Fox's Den. US: Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814651087.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (2004). The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261–1453. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Opeyemi, Oladunjo (6 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela: A Unique World Leader Dies At 95". Nigerian Echo. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, Canada: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Owens, Karen (2013). Franz Joseph and Elisabeth: The Last Great Monarchs of Austria-Hungary. North Carolina, US: McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 9780786476749.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1994). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195086775.

- Prazmowska, Anita (2011) [2004]. A History of Poland (2 ed.). New York, US: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230252356.

- "Prince Muhammed Ali of Egypt and Princess Noal Zaher of Afghanistan Prepare for their Royal Wedding". Hello!. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Princess Astrid". The Belgian Monarchy. n.d. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- Qingzhi Zhao, George (2008). Marriage as Political Strategy and Cultural Expression: Mongolian Royal Marriages from World Empire to Yuan Dynasty. New York. ISBN 9781433102752.

- Roller, Duane (1998). The Building Program of Herod the Great. California, US: University of California Press.

- Ruiz, Enrique (2009). Discriminate Or Diversify. Positivepsyche.Biz crop. ISBN 9780578017341.

- Rushton, Alan R. (2008). Royal Maladies: Inherited Diseases in the Ruling Houses of Europe. BC, Canada: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781425168100.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (2001). Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World. California, US: ABC-CLIO Inc. ISBN 9781576070925.

- Sarma, Rani (2008). "Bella Vista". The Deodis of Hyderabad a Lost Heritage. New Delhi, Inda: Rupa Co. ISBN 9788129127839.

- Schaus, Margaret (2006). Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. New York, US: Routledge. ISBN 9781135459604.

- Schürer, Emil; Millar, Fergus; Vermes, Geza (2014) [1973]. The History of the Jewish People in the Ages of Jesus Christ. 1. IL, US: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Smith, William (1860). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. US: Harvard University. ISBN 9781845110024.

- Stengs, Irene (2009). Worshipping the Great Moderniser: King Chulalongkporn, Patron Saint of the Thai Middle Class. Washington, US: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295989174.

- Thailand Country Study Guide (4th ed.). Washington DC, US: International Business Publications USA. 2007. ISBN 9781433049194.

- Thornton, Michael (1986). Royal Feud: The Dark Side of the Love Story of the Century. New York, US: Random House Publishing. ISBN 9780345336828.

- Thomas, Alastair H. (2010). The A to Z of Denmark. Washington DC, US: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461671848.

- Thomson, David (1961). Europe Since Napoleon. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780140135619.

- "Topics in the History of Genetics and Molecular Biology: The Habsburg Lip". Michigan State University. 2000. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Tribute to mothers' caring nature". The Star. 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Queen Anne Marie". The Greek Monarchy. n.d. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Veit, Veronika (2007). The Role of Women in the Altaic World. Germany: Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447055376.

- Verlag, Starke (1997). Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XV. [Genealogical Handbook of the nobility, Princely houses XV] (in German). ISBN 9783798008342.

- Verzijl, J. H. W. International Law in Historical Perspective. Nova et Vetera Iuris Gentium. III.

- Vork, Justin (2012). Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires. Bloomington, US: iUniverse.com. ISBN 9781475917499.

- Walthall, Anne (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. London. ISBN 9780520254442.

- "Wedding Brings Xhosa, Zulu Tribes Together". Los Angeles Times. California. 2002. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Wortman, Richard (2013). Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy from Peter the Great to the Abdication of Nicholas II. New Jersey, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849697.