Oni

| Part of the series on |

| Japanese mythology and folklore |

|---|

|

| Mythic texts and folktales |

| Divinities |

| Legendary creatures and spirits |

| Legendary figures |

| Mythical and sacred locations |

| Sacred objects |

| Shintō and Buddhism |

| Folklorists |

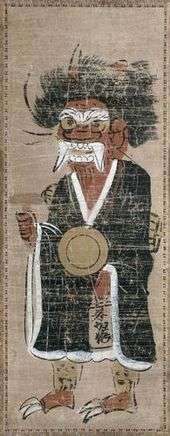

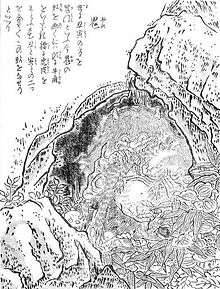

Oni (鬼) are a kind of yōkai from Japanese folklore, variously translated as demons, devils, ogres, or trolls. They are popular characters in Japanese art, literature and theatre.[1]

Depictions of oni vary widely but usually portray them as hideous, gigantic ogre-like creatures with sharp claws, wild hair, and two long horns growing from their heads.[2] They are humanoid for the most part, but occasionally, they are shown with unnatural features such as odd numbers of eyes or extra fingers and toes.[3] Their skin may be any number of colors, but red and blue are particularly common.[4][5]

They are often depicted wearing tiger-skin loincloths and carrying iron clubs called kanabō (金棒). This image leads to the expression "oni with an iron club" (鬼に金棒 oni-ni-kanabō), that is, to be invincible or undefeatable. It can also be used in the sense of "strong beyond strong", or having one's natural quality enhanced or supplemented by the use of some tool. In addition to this, it can mean to go overboard, or be unnecessarily strong or powerful.[6][7]

Origins

The word "oni" is sometimes speculated to be derived from on, the on'yomi reading of a character (隠) meaning to hide or conceal, as oni were originally invisible spirits or gods which caused disasters, disease, and other unpleasant things. These nebulous beings could also take on a variety of forms to deceive (and often devour) humans. Thus the Chinese character 鬼 (pinyin: guǐ; Jyutping: gwai2) meaning "ghost" came to be used for these formless creatures.

The invisible oni eventually became anthropomorphized and took on its modern, ogre-like form, partly via syncretism with creatures imported by Buddhism, such as the Indian rakshasa and yaksha, the hungry ghosts called gaki, and the devilish underlings of Enma-Ō who punish sinners in Jigoku (Hell).They share many similarities with the Arabian Jinn.

Demon gate

Another source for the oni's image is a concept from China and Onmyōdō. The northeast direction was once termed the kimon (鬼門, "demon gate"), and was considered an unlucky direction through which evil spirits passed. Based on the assignment of the twelve zodiac animals to the cardinal directions, the kimon was also known as the ushitora (丑寅), or "Ox Tiger" direction, and the oni's bovine horns and cat-like fangs, claws, and tiger-skin loincloth developed as a visual depiction of this term.[8]

Temples are often built facing that direction, and Japanese buildings sometimes have L-shaped indentions at the northeast to ward oni away. Enryakuji, on Mount Hiei northeast of the center of Kyoto, and Kaneiji, in that direction from Edo Castle, are examples. The Japanese capital itself moved northeast from Nagaoka to Kyoto in the 8th century.[9]

Traditional culture

Some villages hold yearly ceremonies to drive away oni, particularly at the beginning of Spring. During the Setsubun festival, people throw soybeans outside their homes and shout "Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!" ("鬼は外!福は内!", " Oni go out! Blessings come in!").[10] Monkey statues are also thought to guard against oni, since the Japanese word for monkey, saru, is a homophone for the word for "leaving". Folklore has it that holly can be used to guard against Oni.[11] In Japanese versions of the game tag, the player who is "it" is instead called the "oni".[12]

In more recent times, oni have lost some of their original wickedness and sometimes take on a more protective function. Men in oni costumes often lead Japanese parades to ward off any bad luck, for example. Japanese buildings sometimes include oni-faced roof tiles called onigawara (鬼瓦), which are thought to ward away bad luck, much like gargoyles in Western tradition.[13]

Oni are prominently featured in the Japanese children's story Momotaro (Peach Boy), and the book The Funny Little Woman.

Many Japanese idioms and proverbs also make reference to oni. For example, the expression oya ni ninu ko wa oni no ko (親に似ぬ子は鬼の子) means literally "a child that does not resemble its parents is the child of an oni," but it is used idiomatically to refer to the fact that all children naturally take after their parents, and in the odd case that a child appears not to do so, it might be because the child's true biological parents are not the ones who are raising the child. Depending on the context in which it is used, it can have connotations of "children who do not act like their parents are not true human beings," and may be used by a parent to chastise a misbehaving child. Variants of this expression include oya ni ninu ko wa onigo (親に似ぬ子は鬼子) and oya ni ninu ko wa onikko (親に似ぬ子は鬼っ子).[14] There is also a well known game in Japan called kakure oni (隠れ鬼), which means "hidden oni", or more commonly kakurenbo, which is the same as the hide-and-seek game that children in western countries play.

Popular culture

- In Capcom's video game saga Onimusha where the protagonist wields the power of the Oni, and retells the History of Japan with supernatural elements.

- In Rumiko Takahashi's Urusei Yatsura, the female lead, Lum Invader, is an oni alien depicted wearing a tiger-skin bikini and the entire alien race to which she belongs is fashioned after the classical concept of oni.

- Hiroshi Aramata's award winning, bestselling historical fantasy novel Teito Monogatari revolves around the exploits of an oni who is a lieutenant in the Japanese Imperial Army. Dr. Noriko Tsunoda Reider, professor of Japanese Language and Literature at Ohio State University, credits the novel with raising "the oni's status and popularity greatly in modern times."[15]

- Chie Shinohara's manga Ao no Fuuin uses oni as a main theme when the female protagonist is a descendant of a beautiful oni queen who wants to resurrect her kind.

- Japanese symphonic/progressive rock band Shingetsu (新●月) included a piece titled "Oni" (鬼) in their first album. According to Akira Hanamoto, the writer of the song, the oni depicted in this piece is more spirit-like and has no features that would distinguish it as a separate physical entity. While it appears to retain some of the grisly traits of its physical counterparts—enough to make a goat tremble—it is also revealed to be quite timid as it "takes flight" apparently at the sight of a hissing cat.

- Takahashi's Ranma 1/2 features a story in which one of the characters, Kasumi Tendo, is possessed by an oni, causing her to behave in uncharacteristically "evil" (yet humorous) ways.

- The Touhou Project series of shoot-'em-up games has a character named Suika Ibuki, an oni with a massive gourd on her back capable of producing an endless amount of sake; legend has it that no one has seen her sober in her 700-year life. A later game in the series marked the appearance of Yuugi Hoshiguma, Suika's oni associate from a group of four incredibly powerful oni that they both belong to, called the "Four Devas of the Mountains." Yuugi, despite being as great a drinker as Suika while being just as cheerful, is even less of a lightweight than Suika, being able to enter into a fight without seeming intoxicated or even spilling any of the sake in her sake dish.

- In the Mortal Kombat universe, the denizens of the Netherrealm (the series' equivalent of hell) are called Oni (though they represent a drastic deviation from the Japanese concept, being primitive ape-like demons), and the oni character Drahmin's right arm is replaced by a metal club. Another Oni fighter of the series is Moloch.

- In Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z, an Oni called King Yemma runs the Check-In Station in Other World, where he decides which souls go to Heaven and which to Hell.

- The Onis are featured in Season 4 of Jackie Chan Adventures. Tarakudo (voiced by Miguel Ferrer) is the King of the Onis. There are 9 other Oni masks that when worn, the demon trapped in the masks can take over the users well-being and able to control their own tribe of the Shadowkhan.

- In Hellboy: Sword of Storms, Hellboy fought a giant Oni. Before the final blow can be struck with the Sword of Storms, the Oni fades away so that Hellboy can break the Sword of Storms on the statue releasing the brothers Thunder and Lightning.

- Kamen Rider Hibiki, a Japanese tokusatsu series, uses Oni (which is what the Kamen Riders here are referred as) as a main theme of the series. It tells the story about ancient battle between the Oni and the Makamou. In another popular tokusatsu, the Ultra series, it is not uncommon for Oni to appear and do battle with an Ultraman.

- Hyakujuu Sentai Gaoranger, Ogre Tribe Org is the main antagonist to fight the Gaorangers and Power Animals.

- In the popular Japanese manga series One Piece, one of the four emperors Kaido shares similarities with an Oni in both appearance and power.

- In Pokémon, Electabuzz shares similarities with the oni. Sawk and Throh are meant to resemble the blue oni and the red oni, respectively.

- In The Venture Brothers season two episode "I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills", Dr. Venture is haunted by a floating Oni which has followed him from Japan.

- In the video game Muramasa: The Demon Blade, Oni are one of the various enemies the main characters battle.

- In Rumiko Takahashi's manga InuYasha, Oni are common Yokai in the series.

- In the first-person shooter series Shadow Warrior, the protagonist is fighting demonic entities that bear a strong resemblance to Onis.

- The 'Oni' are a form of Samurai inspired NPCs (Non Playable Characters) in Crystal Dynamics' 2013 video game release 'Tomb Raider'

- In the MMORPG "Onigiri" the player's character is an 'Oni'

- In Super Street Fighter IV: Arcade Edition a more powerful "unleashed" form of Akuma is named Oni and features claws, fangs, and horns similar to classical depictions of oni.

- In Yo-kai Watch, many of the creatures found are based on oni. Oni themselves appear as a class of boss enemies. They are distinct between each other, but all have horns. Some also have either claws, horns, or both.

- In the MTV television show Teen Wolf, the Oni were a primary villan, aiding to both Noshiko Yukimura and the Nogitsune during Season 3 part 2.

- In the Supernatural novel Rite of Passage, an oni is the main enemy, terrorizing the town of Laurel Hills, New Jersey and causing a chain of disasters that kills hundreds of people. Eventually its realized that the oni is after the three children it sired with human women eighteen years before. At the end of the story, the oni is killed by Bobby Singer with a rifle shot through its third eye after its separated from its kanabo, the thing that makes it invincible.

- In the video game "Toukiden: Kiwami" the main character is called a slayer, or "demons that hunt demons" and the character's main purpose is to defend the village from a variety of Oni.

- Heavy Metal band Trivium's seventh studio album Silence in the Snow contains an Oni mask on the front.

See also

- Dokkaebi

- Ghosts in Chinese culture

- Jinn (similar etymology and supernatural abilities)

- Kangxi radical 194 (meaning "ghost" or "demon")

- Onibaba (Oni Hag)

- Sazae-oni (Shellfish Oni)

- Unicode Emoji character U+1F479 (👹) representing Japanese Ogre (Oni)

- Ushi-oni (Ox Oni)

- Urusei Yatsura for an anime where the oni are re-imagined as aliens

- Wendigo

- Yōkai

References

- ↑ Lim, Shirley; Ling, Amy (1992). Reading the literatures of Asian America. Temole University Press. p. 242. ISBN 0-87722-935-X.

- ↑ Mack, Carol; Mack, Dinah (1998). A Field Guide to Demons, Fairies, Fallen Angels, and Other Subversive Spirits. Arcade Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 1-55970-447-0.

- ↑ Bush, Laurence C. (2001). Asian horror encyclopedia: Asian horror culture in literature, manga and folklore. Writers Club Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-595-20181-4.

- ↑ Hackin, J.; Couchoud, Paul Louis (2005). Asiatic Mythology 1932. Kessinger Publishing. p. 443. ISBN 1-4179-7695-0.

- ↑ Turne, Patricia; Coulter, Charles Russell (2000). Dictionary of ancient deities. Oxford University Press. p. 363. ISBN 0-19-514504-6.

- ↑ Jones, David E. (2002). Evil in Our Midst: A Chilling Glimpse of Our Most Feared and Frightening Demons. Square One Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 0-7570-0009-6.

- ↑ Buchanan, Daniel Crump (1965). Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-8061-1082-1.

- ↑ Hastings, James (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Part 8. Kessinger Publishing. p. 611. ISBN 0-7661-3678-7.

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephen R. (2006). The samurai and the sacred. Osprey Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 1-84603-021-8.

- ↑ Sosnoski, Daniel (1966). Introduction to Japanese culture. Charles E. Tuttle Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 0-8048-2056-2.

- ↑ How to Escape a Japanese Oni on YouTube

- ↑ Chong, Ilyoung (2002). Information Networking: Wired communications and management. Springer-Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 3-540-44256-1.

- ↑ toyozaki, yōko (2007). 「日本の衣食住」まるごと事典. IBC PUBLISHING. p. 21. ISBN 4-89684-640-0.

- ↑ Buchanan, Daniel Crump (1965). Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-8061-1082-1.

- ↑ Reider, Noriko T. Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present Utah State University Press, 2010. 113. (ISBN 0874217938)

Bibliography

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2003). Mujara 3: Kinki-hen. Japan: Soft Garage. p. 29. ISBN 4861330068.

- Shiryōshitsu Oni Kan

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oni. |