Palembang

| Palembang | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| Other transcription(s) | ||

| • Jawi | ڤاليمباڠ | |

| • Chinese | 巨港 | |

| • Pinyin | Jù gǎng | |

|

Ampera Bridge, the icon of Palembang | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Kota Pempek (City of Pempek), Venetië Van Andalas, Bumi Sriwijaya (The Land of Srivijaya) | ||

| Motto: Palembang BARI (Bersih, Aman, Rapi, Indah) (Palembang: Clean, Safe, Neat, and Beautiful) | ||

Palembang Location of the city in southern Sumatra | ||

| Coordinates: 2°59′10″S 104°45′20″E / 2.98611°S 104.75556°ECoordinates: 2°59′10″S 104°45′20″E / 2.98611°S 104.75556°E | ||

| Country | Indonesia | |

| Province | South Sumatra | |

| Incorporated (city) | 16 June 683 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | H. Harnojoyo | |

| • Vice Mayor | Fitrianti Agustinda | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 369.22 km2 (142.56 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) | |

| Population (2010 census) | ||

| • Total | 1,708,413 | |

| • Density | 4,600/km2 (12,000/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | WIB (UTC+7) | |

| Area code(s) | +62 711 | |

| Website |

www | |

| Palembang | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 巨港 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

Palembang is the second-largest city on Sumatra island after Medan and the capital city of the South Sumatra province in Indonesia. It is one of the oldest cities in the Malay Archipelago and Southeast Asia. Palembang is located on the Musi River banks on the east coast of southern Sumatra, with a land area of 369.22. square kilometres and a population of 1,708,413 people (2014).[1] Palembang is the sixth-largest city in Indonesia after Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung, Medan and Semarang. Its built-up (or metro) area with Talang Kelapa and Rambutan was home to 1,620,429 inhabitants at the 2010 census.

Palembang is one of the oldest cities in Indonesia, and has a history of being the capital city of the Kingdom of Srivijaya, a powerful Malay kingdom, which influenced much of Southeast Asia.[2] The earliest evidence of its existence dates from the 7th century; a Chinese monk, Yijing, wrote that he visited Srivijaya in the year 671 for 6 months. The first inscription in which the name Srivijaya appears also dates from the 7th century, namely the Kedukan Bukit Inscription around Palembang in Sumatra, dated 683.[3]

Palembang's main landmarks include Ampera Bridge and Musi River, the latter of which divides the city into two. The north bank of river in Palembang is known as Seberang Ilir and the south bank of the river in Palembang is known as Seberang Ulu. This city was known as a host city for 2011 Southeast Asian Games. Additionally, 2018 Asian Games is going to be held in the city along with Jakarta.

History

Srivijaya period

The Kedukan Bukit Inscription, which is dated 682 AD, is the oldest inscription found in Palembang. The inscription tells of a king who acquires magical powers and leads a large military force over water and land, setting out from Tamvan delta, arriving at a place called "Matajap," and (in the interpretation of some scholars) founding the polity of Srivijaya. The "Matajap" of the inscription is believed to be Mukha Upang, a district of Palembang.[4]

According to George Coedes, "in the second half of the 9th century Java and Sumatra were united under the rule of a Sailendra reigning in Java...its centre at Palembang."[5]:92

As the capital of the Srivijaya kingdom, this second oldest city in Southeast Asia has been an important trading center in maritime Southeast Asia for more than a millennium. The kingdom flourished by controlling the international trade through the Malacca Straits from the seventh to thirteenth century, establishing hegemony over polities in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Sanskrit inscriptions and Chinese travelogues report that the kingdom prospered as an intermediary in the international trade between China and India. Because of the Monsoon, or biannual seasonal wind, after getting to Srivijaya, traders from China (or India) had to stay there for several months waiting the direction of the wind changes, or had to go back to China (or India). Thus, Srivijaya grew to be the biggest international trade center, and not only the market, but also infrastructures for traders such as lodging and entertainment also developed. It functioned as a cultural center as well.[6] Yijing, a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim who stayed in today’s Palembang and Jambi in 671, recorded that there were more than a thousand Buddhist monks and learned scholars, sponsored by the kingdom to study religion in Palembang. He also recorded that there were many "states" under the kingdom called Srivijaya (Shili Foshi).[7][8]

In 990, an army from the Kingdom of Medang in Java attacked Srivijaya. Palembang was sacked and the palace was looted. Cudamani Warmadewa, however, requested protection from China. By 1006, the invasion was finally repelled. In retaliation, Srivijaya king sent his troops to assist King Wurawari of Luaram in his revolt against Medang. In subsequent battles, Medang Palace was destroyed and the royal family of Medang executed.[9]

In 1068, King Virarajendra Chola of the Chola Dynasty of India conquered what is now Kedah from Srivijaya.[10] Having lost many soldiers in the war and with its coffers almost empty due to the twenty-year disruption of trade, the reach of Srivijaya was diminished. Its territories began to free themselves from the suzerainty of Palembang and to establish many small kingdoms all over the former empire.[11] Srivijaya finally declined with the military expedition by Javanese kingdoms in the thirteenth century.[8]

Post-Srivijaya period

Prince Parameswara fled from Palembang after being crushed by Javanese forces,[12] The city was then plagued by pirates, notably Chen Zuyi and Liang Daoming. In 1407, Chen was confronted at Palembang by the returning Imperial treasure fleet under Admiral Zheng He. Zheng made the opening gambit, demanding Chen's surrender and the pirate quickly signalled agreement while preparing for a surprise pre-emptive strike. But details of his plan had been provided to Zheng by a local Chinese informant, and in the fierce battle that ensued, the Ming soldiers and Ming superior armada finally destroyed the pirate fleet and killed 5,000 of its men. Chen was captured and held for public execution in Nanjing in 1407. Peace was finally restored to the Strait of Malacca as Shi Jinqing was installed as Palembang's new ruler and incorporated into what would become a far-flung system of allies who acknowledged Ming supremacy in return for diplomatic recognition, military protection, and trading rights.[13][14] Palembang is called Chinese: 巨港; pinyin: Jù gǎng; literally: "Giant Harbour".

Palembang Sultanate period

After Demak Sultanate fell under Kingdom of Pajang, a Demak nobleman, Geding Suro with his followers fled to Palembang and established a new dynasty. Islam become dominant in Palembang since this period.[12] Grand Mosque of Palembang built in 1738 under the reign of Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin I Jaya Wikrama,[15] completed in 1748.[16] Settlement flourished along Musi River bank, some of houses built on rafts.[12] The Sultanate enacted legislation that portion downstream of Palembang (Ilir Palembang) where the palace is located, is intended for residents of Palembang. While foreigners are not citizens of Palembang is at the opposite portion of the palace called Ulu Palembang.[17]

Several local rivals, such as Banten, Jambi, and Aceh threatened the existence of the Sultanate, meanwhile Dutch East India Company established a trade post in Palembang in 1619. In 1642, the company obtained monopoly right over pepper trading in the port. Tension mounted between the Dutch and the locals, peaked at 1657 when a Dutch ship was attacked in Palembang, gave a signal to the company to launch a punitive expedition in 1659 which burned the city to the ground.[12]

During Napoleonic Wars in 1812, the sultan at that time, Mahmud Badaruddin II repudiated British claims to suzerainty, which was responded by British by attacking Palembang, sacking the court, and installing sultan's more cooperative younger brother, Najamuddin to the throne. The Dutch attempted to recover their influence at the court in 1816, but Sultan Najamuddin was uncooperative with them. An expedition launched by the Dutch in 1818 and captured Sultan Najamudin and exiled him to Batavia. A Dutch garrison was established in 1821, but sultan attempted an attack and a mass poisoning to the garrison, which were intervened by Dutch. Mahmud Badaruddin II was exiled to Ternate, and his palace was burned to the ground. The Sultanate was later abolished by Dutch and direct colonial rule was established.[12]

Colonial period

From the late nineteenth century, with the introduction of new export crops by the Dutch companies, Palembang rose again as an economic center. In the 1900s, the development of the petroleum and rubber industries caused unprecedented economic growth, which brought about the influx of migrants, an increase in urbanization, and development of the socioeconomic infrastructure.[18]

The emergence of rubber cultivation in South Sumatra began in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, several major Western companies entered the area and operated rubber plantations. From the mid-1920s, rubber became the biggest export crop in the area, surpassing robusta coffee. Although there were large rubber estates owned by Western enterprises, rubber in Palembang was produced mainly by smallholders. By the 1920s, the Residency of Palembang (today’s South Sumatra province) was ranked sixth among the regions of smallholder rubber production, becoming the largest of the smallholder rubber regions in the 1940s, producing 58,000 tons of rubber.[18]

There were three petroleum companies in 1900: the Sumatra-Palembang Petroleum Company (Sumpal); the French-owned Muara Enim Petroleum Company; and the Musi Ilir Petroleum Company. The Sumpal was soon assimilated into the Royal Dutch, and the Muara Enim Co. and the Musi Ilir Co. were also assimilated into the Royal Dutch, in 1904 and in 1906, respectively. Based on this assimilation, Royal Dutch and Shell established the BPM, the operating company of Royal Dutch Shell, and opened an oil refinery at Plaju, on the shore of the Musi River in Palembang, in 1907. While BPM was the only operating company in this area until the 1910s, American oil companies launched their business in the Palembang region from the 1920s. Standard Oil of New Jersey established a subsidiary, the American Petroleum Company, and, to prevent Dutch laws to restrict the activities of foreign firms, the American Petroleum Company established its own subsidiary, the Netherlands Colonial Oil Company (Nederlandche Koloniale Petroleum Maatschapij, NKPM). The NKPM began to establish itself in Sungai Gerong area in the early 1920s, and completed the construction of pipelines to send 3,500 barrels per day from their oilfields to the refinery at Sungai Gerong. The two refinery complexes were like enclaves, separate urban centers with houses, hospitals, and other cultural facilities built by the Dutch and Americans. In 1933, Standard Oil incorporated the NKPM holdings into the Standard Vacuum Company, a new joint venture corporation, which was renamed the Standard Vacuum Petroleum Maatschappij (SVPM). Caltex (a subsidiary of the Standard Oil California and Texas Company) secured extensive exploration concessions in Central Sumatra (Jambi) in 1931. By 1938, the production of crude oil in the Netherlands East Indies totaled 7,398,000 metric tons, and the shares of the BPM reached seventy two percent, while the NKPM (StandardVacuum)’s share was twenty eight percent. Whereas the most prolific area in crude oil production was East Kalimantan until the late 1930s, since then Palembang and Jambi took over the position. All crude oil production in the NEI was processed at seven refineries at this time, especially at three large export refineries: the NKPM plant at Sungai Gerong, the BPM refineries at Plaju, and the one in Balikpapan. Thus Palembang held two of the three biggest oil refineries in the archipelago.[18]

In the 1920s, with the guidance of Thomas Karsten, one of the pioneers of architectural project in the cities in the Netherlands East Indies, the Traffic Commission (Komisi Lalu Lintas) of Palembang was to improve inland transportation conditions in Palembang. The Commission reclaimed land from rivers and asphalted roads. Traffic plan in the city of Palembang was based on Karsten’s city plan, in which the Ilir was in the form of a road ring, starting form an edge of the Musi River. From then they built many smaller bridges on both sides of the Musi River, including the Wilhelmina Bridge over the Ogan River that vertically divides the Ulu area. The bridge was built in 1939 with the intention of connecting oil refineries in the eastern bank to western bank, where the Kretapati train station was located.In the late 1920s, ocean steamers navigated the Musi River on a regular basis.[18]

In the 1930s, the Residency of Palembang was one of the "three giants" in the export economy of the Netherlands East Indies, together with the East Sumatran Plantation Belt and Southeast Kalimantan, and the city of Palembang was the most populous urban center outside Java. Its population was 50,703 in 1905; it reached 109,069, while the population of Makassar and Medan was 86,662 and 74,976, respectively. It was surpassed only by three larger cities located in Java: Batavia, Surabaya and Semarang.[18]

Japanese occupation period

Palembang targeted by Japanese forces because the city was the location of some finest oil refineries in Southeast Asia. An oil embargo imposed on Japan by the United States, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. With the area's abundant fuel supply and airfield, Palembang offered significant potential as a military base to both the Allies and the Japanese.[19][20]

The battle occurred between 13–16 February 1942. While the Allied planes attacked the Japanese ships on 13 February, Kawasaki Ki-56 transport planes of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Chutai, Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF), dropped Teishin Shudan (Raiding Group) paratroopers over Pangkalan Benteng airfield. At the same time Mitsubishi Ki-21 bombers from the 98th Sentai dropped supplies for paratroopers. The formation was escorted by a large force of Nakajima Ki-43 fighters from the 59th and 64th Sentai. As many as 180 men from the Japanese 2nd Parachute Regiment, under Colonel Seiichi Kume, dropped between Palembang and Pangkalan Benteng, and more than 90 men came down west of the refineries at Plaju. Although the Japanese paratroopers failed to capture the Pangkalan Benteng airfield, at the Plaju oil refinery they managed to gain possession of the entire complex, which was undamaged. However, second oil refinery in Sungai Gerong was successfully demolished by the Allies. A makeshift counter-attack by Landstorm troops and anti-aircraft gunners from Prabumulih managed to retake the complex but took heavy losses. The planned demolition failed to do any serious damage to the refinery, but the oil stores were set ablaze. Two hours after the first drop, another 60 Japanese paratroopers were dropped near Pangkalan Benteng airfield.[19][20]

As the Japanese landing force approached Sumatra, the remaining Allied aircraft attacked it, and the Japanese transport ship Otawa Maru was sunk. Hurricanes flew up the rivers, machine-gunning Japanese landing craft. However, on the afternoon of 15 February, all Allied aircraft were ordered to Java, where a major Japanese attack was anticipated, and the Allied air units had withdrawn from southern Sumatra by the evening of 16 February 1942. Other personnel were evacuated via Oosthaven (now Bandar Lampung) by ships to Java or India.[19][20]

National revolution period

On 8 October 1945, Resident of South Sumatra, Adnan Kapau Gani with all Gunseibu officers raise the Indonesian flag during a ceremony. In that day, it was announced that Palembang Residency was under control of Republicans.[21]

Palembang was the location of Pertempuran Lima Hari Lima Malam (Five Days and Nights Battle) between the Republicans and the Dutch on 1–5 January 1947. There were three fronts during the battle which are Eastern Ilir front, Western Ilir front, and Ulu front. The battle ended with a cease fire and the Republican forces was forced to retreat as far as 20 kilometers from Palembang.[22][23]

During the occupation, the Dutch formed the federal state of South Sumatra on September, 1948.[24] After the transfer of sovereignty on 27 December 1949, South Sumatra State, along with other federal states and the Republic would form short-lived United States of Indonesia before the states abolished and integrated into the Republic on 17 August 1950.[25]

Old Order and New Order period

During PRRI/Permesta rebellion, Dewan Garuda (Garuda Council) formed in South Sumatra which on 15 January 1957 under Lieutenant Colonel Barlian took over the local government of South Sumatra.

In April 1962, Indonesian government started the construction of Ampera Bridge which was completed and officially opened for public on 30 September 1965 by Minister/Commander of the Army Lieutenant General Ahmad Yani on 30 September 1965, only hours before he was killed by troops belonging to the 30 September Movement. At first, the bridge was known as the Bung Karno Bridge, after the president, but following his fall, it was renamed the Ampera Bridge.[26] A second bridge in Palembang which crosses Musi River, Musi II Bridge was built on 4 August 1992.[27]

On 6 December 1988, Palembang city area expanded, with 9 villages from Musi Banyuasin integrated into 2 new districts of Palembang and 1 village from Ogan Komering Ilir integrated into Seberang Ulu I District.[27]

Riot also plagued Palembang during May 1998 riot in Indonesia. Ten shops were burned, more than a dozen cars were burned by rioters, and dozens of people were injured by rocks thrown by students marching to the Provincial People's Representative Council office of South Sumatra. Thousands of police and soldiers were put on guard at various points in the city. The Volunteer Team for Humanity (Indonesian: Tim Relawan untuk Manusia, or TRUK) reported that cases of sexual assault also took place.[27]

Reformasi period

In 2001, a sport complex along with its main stadium, Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium, was built in Jakabaring, completed in 2004. It served as venues for 2004 Pekan Olahraga Nasional. Palembang became host of Pekan Olahraga Nasional in 2004 after 47 years it was last held outside Java and 51 years in Sumatra.[28] 7 years later, Palembang became the host of more prestigious sporting event, 2011 Southeast Asian Games along with Jakarta. In 2013, Indonesian government decide to replace the host of 2013 Islamic Solidarity Games from Pekanbaru to Palembang because several problems occurred in the former host, including Riau Governor, Rusli Zainal who stumbled over a corruption scandal.[29] Palembang, together again with Jakarta, will host the 2018 Asian Games.[30]

Sixth president of Indonesia, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, declared Palembang as a "Water Tourism City" on 27 September 2005.[31] More further on 5 January 2008, Palembang publicised its tourist attractions with the slogan "Visit Musi 2008".[32]

Palembang completed its first flyover at Simpang Polda in September 2008.[33] Second flyover in Jakabaring completed in 2015.[34] Two more flyovers will be built before 2018.[35] In 2010, Palembang launched its bus transit system, Transmusi.[36] In April 2015, the government started the construction of Palembang's first toll road (Palembang-Inderalaya).[37] Construction of light rail transit system from Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II International Airport to Jakabaring was started in December 2015.[38]

Etymology

The word "Palembang" is derived from two words in Malay "pa" and "lembang". "Pa" or "Pe" in Malay is a prefix which indicates a place or situation meanwhile "lembang" or "lembeng" means lowland, a swollen root because inundated by water for a long time. In other words, "Palembang" literally means "the place which was constantly inundated by water".[39]

Geography and climate

Geography

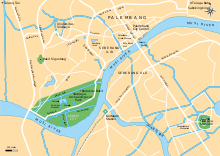

At 2°59′10″S 104°45′20″E / 2.98611°S 104.75556°E, Palembang occupies 400.61 km2 of vast lowland area east of Bukit Barisan Mountains in southern Sumatra with average elevation of 8 meters,[40] approximately 105 km from nearby coast at Bangka Strait. One of the largest rivers in Sumatra, the Musi River, runs through the city, dividing the city area into two major parts which are Seberang Ilir in the north and Seberang Ulu in the south. Palembang is also located on the confluence of two major tributaries of Musi River, which are Ogan River and Komering River. The river's water level is influenced by tidal cycle. In rainy season, many areas on the city are inundated by the river's tide.[41]

Palembang's topography is quite different between Seberang Ilir and Seberang Ulu area. Seberang Ulu topography is relatively flat, meanwhile Seberang Ilir topography is more rugged with altitude variation between 4 meters to 20 meters.[41]

Climate

Palembang is located in the tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af) with significant rainfall even in its driest months. The climate in Palembang is often described with "hot, humid climate with a lot of rainfall throughout the year". The annual average temperature is around 27.3 °C (81.1 °F). Average temperatures are nearly identical throughout the year in the city. Average rainfall annually is 2,623 milimetres.[42] During its wettest months, the city's lowlands are frequently inundated by torrential rains. However, in its driest months, many peatlands around the city dried, making them more vulnerable to wildfires, causing haze in the city for months.

| Climate data for Palembang | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.8 (87.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.1 (88) |

31.83 (89.28) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.2 (81) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.33 (81.21) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.91 (73.22) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 277 (10.91) |

262 (10.31) |

329 (12.95) |

263 (10.35) |

213 (8.39) |

122 (4.8) |

104 (4.09) |

107 (4.21) |

120 (4.72) |

186 (7.32) |

274 (10.79) |

366 (14.41) |

2,623 (103.25) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169 | 118 | 130 | 150 | 174 | 127 | 130 | 149 | 118 | 160 | 132 | 120 | 1,677 |

| Source #1: Climate-Data.org[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst[44][45] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

Palembang is roughly divided by Musi River into two major areas known as Seberang Ilir (lit. "downstream bank") in the north and Seberang Ulu (lit. "upstream bank") in the south.

Seberang Ilir is the main economic and political centre in Palembang. Some areas such as 16 Ilir, Cinde, and Km 5 are the major retail hub in Palembang while other areas like Ilir Barat Permai, Kampus, and Patal Pusri are growing into major business centres contained a prominent portion of the city's highrises. Major residential areas in Seberang Ilir such as Tangga Buntung, Bukit Besar, Sekip, Pakjo, Kenten, Pasar Kuto, and Lemabang.

Seberang Ulu is divided into three main neighbourhoods which are Plaju, Kertapati, and Jakabaring. Seberang Ulu is less developed than its counterpart, but this area is undergoing massive development, especially in Jakabaring, with the construction of business center, government building, and the most notably is the construction of the city's sport complex, Jakabaring Sport City.

Administrative division

Palembang consist of 16[46] kecamatan (districts), which in turn sub-divided into 107[47] kelurahan (subdistricts/administrative villages):

- Alang-Alang Lebar

- Bukit Kecil

- Gandus

- Ilir Barat I

- Ilir Barat II

- Ilir Timur I

- Ilir Timur II

- Kalidoni

- Kemuning

- Kertapati

- Plaju

- Sako

- Seberang Ulu I

- Seberang Ulu II

- Sematang Borang

- Sukarame

Demography

The local language of Palembang, Musi, belongs to the same group as Malay. There are also Palembang residents originating from other parts of South Sumatra. They have their own regional languages, such as Komering, Lahat, Rawas and Semendo. There are also people that came from outside South Sumatra. Most of them are Javanese, Chinese, Arab, Indian, Minangkabau or Sundanese.

Palembang's primary religion is Islam, but many of the inhabitants also practice Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism.

Transport

Palembang has networks of mini-bus routes for the main form of public transport and the new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, Trans Musi as well.

- Corridor 1 : Bus stop below the Ilir part of Ampera Bridge - Alang Alang Lebar Bus Station (KM 12)

- Corridor 2 : Perumnas Bus Station - PIM (Palembang Indah Mall)

- Corridor 3 : Plaju - PS Mall (Palembang Square Mall)

- Corridor 4 : Jakabaring - Karya Jaya Bus Station (Kertapati)

- Corridor 5 : Alang Alang Lebar Bus Station (KM 12) - Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II International Airport

- Corridor 6 : Pusri - Palembang Square (PS)

- Corridor 7 : Kenten - Dempo (Coming Soon)

- Corridor 8 : Alang Alang Lebar Bus Station (KM 12) - Terminal Karya Jaya (Kertapati)

- Pangkalan Balai Corridor : Alang Alang Lebar Bus Station (KM 12) - Pangkalan Balai

- Indralaya Corridor : Terminal Karya Jaya - Indralaya

- Unsri Corridor : Unsri Bukit - Unsri Indralaya

Palembang also has a large number of taxis. The number keeps rising since the Pekan Olahraga Nasional 2004 and SEA Games 2011, which both were held in Palembang.

There are also traditional and speed boats that serve the people who live near the riverside. The traditional boats are called "Keteks" or sampans.

The city is served by Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II International Airport which has scheduled flights to many cities in Indonesia and to Singapore by Silk Air and Jetstar, and also to Kuala Lumpur by AirAsia. This airport also serves other cities around South Sumatra Province.

Palembang also has three main harbours, Tanjung Api-api Harbour (which is the International harbour of Palembang, located on sea-shore, 68 kilometres from the city), 36 Ilir Harbour and Boom Baru Harbour on riverside. From Tanjung Api-api Harbour frequent ferries connect Palembang to Tanjung Kalian Harbour in western side of Bangka Island (it takes only 2 hours on ferries from Tanjung Api-api to Bangka), Bangka-Belitung Islands Province, and also ferries to Batam Island.

Tanjung Api Api Harbour is now fully operational. It opened at 10.00 am on 11 December 2013. It is an international port so it can be visited by all kind of boats from all over the globe.

Railway tracks connect Palembang to Bandar Lampung, Tanjung Enim, Lahat dan Lubuk Linggau. The largest railway station in Palembang is Kertapati railway station.

The first line of South Sumatra LRT is under construction now to face future traffic congestion which is predicted to be the worst nationwide by 2019 if Palembang did not do any urban transport improvement. There will be 13 stations for the LRT system, namely as follows:

- Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II Airport station

- Asrama Haji station

- Telkom station

- RSUD station

- POLDA station

- Demang Lebar Daun station

- Palembang Icon station

- Dishub Kominfo station

- Pasar Cinde station

- Jembatan Ampera station

- Gubernur Bastari station

- Stadion Jakabaring station

- OPI station

Economy

Palembang's economy has been developed significantly since it became a host for a National Sporting Event in 2004.

Tourism and recreation

- Musi River, about 750 km along the river which divides the city into two parts, namely Palembang Seberang Ulu and Sebrang Ilir. It is one of the longest river in Sumatra. Since early of its history, the Musi River has become the economic lifeblood of Palembang city and South Sumatran region in general. Along the river banks, there are some landmarks, tourism sites and cultural attractions, such as the Ampera Bridge, Kuto Besak Fort, the Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II Museum, Kemaro Island, 16 Ilir Market, traditional raft houses, Pertamina's oil refineries, Pupuk Sriwijaya (PUSRI) fertilizer plants, Bagus Kuning beach, Musi II Bridge, Al Munawar Mosque, etc.

- Ampera Bridge, main city landmark, is a bridge crossed over 1,177 metres above the Musi River which connects Seberang Ulu and Seberang Ilir area of Palembang.

- Great Mosque of Palembang, also known as the Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II Mosque, is located in the city centre.

- Benteng Kuto Besak, situated on the northern bank of the Musi River and adjacent to Ampera Bridge, this fort is one of the Palembang Darussalam Sultanate of heritage buildings. The fort's interior have been turned into military hospital of the Tentara Nasional Indonesia, specifically the Health Department of Military Area Command II/Sriwijaya (Kesehatan Daerah Militer II/Sriwijaya).

- Kantor Ledeng, located in the city centre, at first this building serves as a water tower because it serves to supply the water throughout the city. Today this building serves as the Office of the Mayor of Palembang

- Kambang Iwak, a lake situated in the tourist centre of the city, close to Palembang mayor's residence. On the banks of this lake, there is a park and recreation arena which is always crowded on holidays.

- Punti Kayu Tourism Forest, city forest located about 6 miles from the city centre with an area of 50 ha and since 1998 designated as protected forests. In this forest there is a family recreation area and a local shelter a group of monkeys: long-tail macaque (Macaca fascicularis) and monkey (Macaca nemistriana) under the Sumatran Pine wood (Pinus mercussi).[48]

- Sriwijaya Kingdom Archaeological Park, the remnants of Sriwijaya site located on the banks of the River Musi. There is an inscription and stone relics, complex of ancient pond, artificial island and canals dated from the Srivijayan kingdom in this area. The Srivijaya Museum is located in this complex.

- Bukit Seguntang archaeological park, located in the hills west of Palembang city. In this place there are many relics and tombs of the ancient Malay-Srivijayan king and nobles.

- People's Struggle Monument (Indonesian: Monumen Perjuangan Rakyat), located in the city centre, adjacent to the Great Mosque and Ampera Bridge. As its name in this building there are relics of history in the colonial period.

- Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II Museum, located near the Ampera Bridge and adjacent to Benteng Kuto Besak. The building located in the former royal palace of Palembang Sultanate. The museum displayed the relics and historical objects with collections spanned from Srivijaya Kingdom period to Palembang Darussalam Sultanate era.

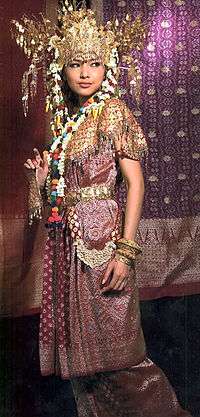

Culture

Since ancient times, Palembang has been a cosmopolitan port city which absorbs neighbouring, as well as foreign, cultures and influences. The influences and cultures of coastal Malay, inland Minangkabau, Javanese, Indian, Chinese and Arab, has created a rich Palembang culture. Throughout its history, Palembang has attracted migrants from other regions in the archipelago, and has made this city as a multi-cultural city. Although today the city had lost its function as the major port city in the archipelago, the remnants of its heyday still evident in its culture. Most of its population was then adopted the culture of coastal Malays and Javanese. Even now it can be seen in its culture and language. Word such as "wong (person)" is an example of Javanese loanword in Palembang language. Also the Javanese knight and noble honorific titles, such as Raden Mas or Raden Ayu is used by Palembang nobles, the remnant of Palembang Sultanate courtly culture. The tombs of the Islamic heritage was not different in form and style with Islamic tombs in Java.

Cuisine

Palembang is famous for its local cuisine called pempek Palembang. It is a Pempek served in sweet and sour sauce called kuah cuko. Another Palembang signature dishes are tekwan, model, mie celor, laksan and lakso, and also pindang patin (pangasius in sweet and sour soup).

Sport

Jakabaring Sport City

Jakabaring Sport City ia a sport complex located 5 kilometres southeast from Palembang city centre, across the Musi River through Ampera Bridge in Jakabaring, Seberang Ulu I area. It was the main venue of 2011 Southeast Asian Games. Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium, one of the largest stadium in Indonesia, is located within this complex. The complex consists of Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium football field, Dempo sport hall, Ranau sport hall, Athletic stadium, Aquatic center, Baseball and Softball field, Shooting range, Athlete lodging, Artificial lake for outdoor water sports (rowing, water ski, dragon boat) and Golf course. Two matches were staged at the stadium in the AFC Asian Cup continued in 2007, the Group D qualifier between Saudi Arabia and Bahrain as well as grabbing a third place between South Korea and Japan. The 2011 Southeast Asian Games was held at Palembang along with Jakarta in November, 2011. The opening and closing ceremonies held in Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium. This sport complex also planned to host the 2018 Asian Games in Indonesia along with Jakarta and Bandung in West Java.

Sriwijaya F.C.

Sriwijaya Football Club, which is commonly referred to as SFC, is an Indonesian football club based in Palembang, Province of South Sumatra, Indonesia.

Education

Universities in Palembang:

- University of Sriwijaya

- State Polytechnic of Sriwijaya Palembang

- State Islamic University of Raden Fatah Palembang

- School of Journalism Indonesia. First Journalism School in Indonesia, SJI was inaugurated by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono at the top of National Press Day (HPN) in Palembang, 9 February 2010. School of Journalism is the first international journalism school in Indonesia under UNESCO.

- Universitas Bina Darma

- Universitas Bina Nusantara - Unit Sumber Belajar Jarak Jauh

- Universitas Indo Global Mandiri

- Universitas Muhammadiyah Palembang

- Universitas Palembang

- Universitas Sjakhyakirti

- Universitas IBA

- Universitas Taman Siswa

- Universitas PGRI

- Universitas Kader Bangsa

- Universitas Tridinanti

- Universitas Terbuka

- Politeknik Akamigas Palembang

- Multi Data Palembang

- Universitas Musi Charitas

Top Senior High Schools in Palembang:

- SMA Xaverius 1 Palembang

- SMA Negeri 5 Palembang

- SMA Negeri Sumatera Selatan

- SMA Xaverius 3 Palembang

- SMA Ignatius Global School (IGS) Palembang

- Sekolah Kusuma Bangsa

- SMA Negeri 1 Palembang

- SMA Negeri 3 Palembang

- SMA Plus Negeri 17 Palembang

- SMA Negeri 6 Palembang

Top Junior High Schools in Palembang:

- SMP Xaverius 1 Palembang

- SMP Xaverius Maria Palembang

- SMP Ignatius Global School (IGS) Palembang

- SMP Sekolah Palembang Harapan (SPH) Palembang

- SMP Kusuma Bangsa Palembang

- SMP Negeri 1 Palembang

- SMP Negeri 9 Palembang

Twin towns – Sister cities

-

Belgorod, Russia

Belgorod, Russia -

Moscow Oblast, Russia

Moscow Oblast, Russia -

The Hague, Netherlands

The Hague, Netherlands -

Venice, Italy

Venice, Italy -

Manchester, United Kingdom

Manchester, United Kingdom -

Neiva, Colombia[49]

Neiva, Colombia[49]

References

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/php/indonesia-sumatera-admin.php

- ↑ Munoz. Early Kingdoms. p. 117.

- ↑ Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell Tryon (1995). "The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives".

- ↑ George Coedès, Les inscriptions malaises de Çrivijaya, BEFEO 1930

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1918). "Le Royaume de Çrīvijaya". Bulletin de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient (18 ed.). 6: 1–36.

- ↑ Nas, Peter J. M. (1995). "Palembang: The Venice of the East," in Issues in Urban Development: Case Studies from Indonesia. Leiden: CNWS. pp. 133–134.

- 1 2 Andaya, Barbara Watson (1993). To Live as Brothers: Southeast Sumatra in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ Munoz. Early Kingdoms. p. 151.

- ↑ The Cambridge Economic History of India: c.1200-c.1750 herausgegeben by Tapan Raychaudhuri, Irfan Habib, Dharma Kumar p.40

- ↑ Munoz. Early Kingdoms. p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schellinger, Paul E.; Salkin, Robert M., eds. (1996). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. New York: Routledge. p. 663. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- ↑ Ta Sen, Tan (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- ↑ "China's Great Armada - National Geographic Magazine". National Geographic. 2012-05-15. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ Ardhani Reswari, 2013

- ↑ Zein, 1999

- ↑ Firmansyah, Rangga (10 November 2014). "VERNACULAR VALUE of KAMPUNG KOTA ( Case studi at Kampung Ulu Sattlement of Musi River, Palembang City)" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yeo, Woonkyung (2012). Palembang in the 1950s: The Making and Unmaking of a Region. University of Washington.

- 1 2 3 "The Battle for Palembang". www.dutcheastindies.webs.com. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- 1 2 3 "The Japanese Invasion of Sumatra Island". www.dutcheastindies.webs.com. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ Notosusanto, Nugroho (2008). Sejarah nasional Indonesia: Zaman Jepang dan zaman Republik Indonesia, ±1942-1998. Balai Pustaka.

- ↑ Notosusanto, Nugroho; Poesponegoro, Marwatidjoened (1987). Sejarah Indonesia V. Balai Pustaka.

- ↑ Dimjati, M (1951). Sedjarah Perdjuangan Indonesia. Djakarta: Widjaja.

- ↑ Ricklefs, M.C. (2008). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 263.

- ↑ Reid (1974), pages 170–172; Ricklefs (1991), pages 232–233; "The National Revolution, 1945–50". U.S. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Imelda Akmal (Ed) (2010). Wiratman: Momentum & Innovation 1960-2010. Jakarta: Mitrawira Aneka Guna. ISBN 978-602-97997-0-5.

- 1 2 3 Winda, Heny (23 October 2012). "Kerusuhan Di Kota Palembang Pada Bulan Mei Tahun 1998 dan Dampaknya Terhadap Masyarakat Kota Palembang di Bidang Politik, Ekonomi dan Sosial (1998-2003)". UNSRI.

- ↑ "Dari Senayan ke Jakabaring | Republika Online". Republika Online. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Keputusan Akhir, ISG Digelar di Palembang". detiksport. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ Sasongko, Tjahjo (28 July 2014). "Setelah 1962, Jakarta Kembali Tuan Rumah Asian Games" – via kompas.com.

- ↑ "Walau Ada Sungai Musi, Palembang Belum Siap Jadi Kota Wisata Air". detiknews. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Blog-SahatSimarmata: Visit Musi 2008". sahatsimarmata.blogspot.co.id. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Gubernur Resmi Soft Opening Fly Over". Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Akhirnya Fly Over Simpang Jakabaring Dibuka". Sriwijaya Post. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "2 Fly Over Baru Akan Di Bangun Tahun 2016". www.sriwijayatv.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Ujicoba Transmusi". www.antaranews.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "FOTO: Jokowi Resmikan Ground Breaking Tol Palindra". SINDOnews. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Pemasangan tiang pancang LRT Palembang mulai dikerjakan". www.antarasumsel.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Sejarah Kota Palembang".

- ↑ "Keadaaan Geografis - Pemerintah Kota Palembang". palembang.go.id. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- 1 2 Argyantoro, Arvi; Samyahardja, Puthut; Medawaty, Ida. "Dampak Kenaikan Muka Air Sungai Di Kota Palembang". Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Permukiman.

- ↑ "Iklim: Grafik iklim - Palembang , grafis Suhu, tabel Iklim - Climate-Data.org". id.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- ↑ http://en.climate-data.org/location/764268/

- ↑ ftp://ftp-cdc.dwd.de/pub/CDC/observations_global/CLIMAT/multi_annual/sunshine_duration/1961_1990.txt

- ↑ ftp://ftp-cdc.dwd.de/pub/CDC/help/stations_list_CLIMAT_data.txt

- ↑ "Direktori" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Palembang. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Beranda" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Palembang. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Punti Kayu: Sumatran Jungle Tours In Palembang, South Sumatera". 1 December 2011.

- ↑ http://www.deplu.go.id/bogota/Pages/CountryProfile.aspx?l=en

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palembang. |

- Official website - in Indonesian

Palembang travel guide from Wikivoyage

Palembang travel guide from Wikivoyage