Pentoxifylline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌpɛntɒkˈsɪfᵻlin, -ɪn/ |

| Trade names | Many names worldwide[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685027 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | C04AD03 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 10-30%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic and via erythrocytes |

| Biological half-life | 0.4-0.8 hours (1-1.6 hours for active metabolite)[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (95%), faeces (<4%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

6493-05-6 |

| PubChem (CID) | 4740 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7095 |

| DrugBank |

DB00806 |

| ChemSpider |

4578 |

| UNII |

SD6QCT3TSU |

| KEGG |

D00501 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL628 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

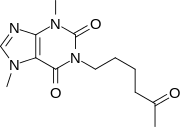

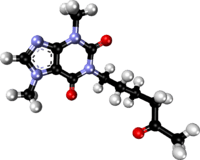

| Formula | C13H18N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 278.31 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pentoxifylline (INN, BAN, USAN) or oxpentifylline (AAN)[3] is a xanthine derivative used as a drug to treat muscle pain in people with peripheral artery disease.[4] It is generic and sold under many brand names worldwide.[1]

Medical uses

Its primary use in medicine is to reduce pain, cramping, numbness, or weakness in the arms or legs which occurs due to intermittent claudication, a form of muscle pain resulting from peripheral artery diseases.[4] This is its only FDA, MHRA and TGA-labelled indication.[3][5][6]

Adverse effects

Common side effects are belching, bloating, stomach discomfort or upset, nausea, vomiting, indigestion, dizziness, and flushing. Uncommon and rare side effects include angina, palpitations, hypersensitivity, itchiness, rash, hives, bleeding, hallucinations, arrhythmias, and aseptic meningitis.[2][3][5][6]

Contraindications include intolerance to pentoxifylline or other xanthine derivatives, recent retinal or cerebral haemorrhage, and risk factors for haemorrhage.[2]

Co-administration of pentoxifylline and sodium thiopental may cause death by acute pulmonary edema in rats.[7]

Mechanism

Like other methylated xanthine derivatives, pentoxifylline is a competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor[8] which raises intracellular cAMP, activates PKA, inhibits TNF[9][10] and leukotriene [11] synthesis, and reduces inflammation and innate immunity.[11] In addition, pentoxifylline improves red blood cell deformability (known as a haemorrheologic effect), reduces blood viscosity and decreases the potential for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation.[12] Pentoxifylline is also an antagonist at adenosine 2 receptors.[13]

Effect on seizure

In a study, the effect of pentoxifylline as a phosphodiestrase inhibitor was study on the pentylenetetrazol-induced seziure in the wild-type mice. Pentoxifylline in that study reduced the anti-convulsive effect of H-89 and reduced the seizure threshold.[14]

Research

There is some evidence that pentoxifyllinenon can lower the levels of some biomarkers in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis but evidence is insufficient to determine if the drug is safe and effective for this use.[15] Animal studies have been conducted exploring the use of pentoxifylline for erectile dysfunction and also human studies on Peyronie's disease.[16][17]

See also

- Lisofylline, an active metabolite of pentoxifylline

- Propentofylline

References

- 1 2 Drugs.com drugs.com international listings for Pentoxifylline. Page accessed Feb 1, 206

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Trental, Pentoxil (pentoxifylline) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "PRODUCT INFORMATION TRENTAL® 400" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. sanofi-aventis australia pty limited. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- 1 2 Salhiyyah K, Senanayake E, Abdel-Hadi M, Booth A, Michaels JA (2012). "Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD005262. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005262.pub2. PMID 22258961.

- 1 2 "PENTOXIFYLLINE tablet, extended release [Apotex Corp.]". DailyMed. Apotex Corp. February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Trental 400 - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Sanofi. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ Pereda J, Gómez-Cambronero L, Alberola A, Fabregat G, Cerdá M, Escobar J, Sabater L, García-de-la-Asunción J, García-de-la-Asuneión J, Viña J, Sastre J (2006). "Co-administration of pentoxifylline and thiopental causes death by acute pulmonary oedema in rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (4): 450–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706871. PMC 1978439

. PMID 16953192.

. PMID 16953192. - ↑ Essayan DM (2001). "Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 108 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.119555. PMID 11692087.

- ↑ Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R (2008). "Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition". Clinics. 63 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322008000300006. PMC 2664230

. PMID 18568240.

. PMID 18568240. - ↑ Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U (1999). "Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 159 (2): 508–11. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804085. PMID 9927365.

- 1 2 Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ (2005). "Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses". Journal of Immunology. 174 (2): 589–94. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.589. PMID 15634873.

- ↑ Ward A, Clissold SP (1987). "Pentoxifylline. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 34 (1): 50–97. doi:10.2165/00003495-198734010-00003. PMID 3308412.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F (2008). "Efficacy of pentoxifylline in the management of microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes". Current Diabetes Reviews. 4 (1): 55–62. doi:10.2174/157339908783502343. PMID 18220696.

- ↑ Hosseini-Zare MS, Salehi F, Seyedi SY, Azami K, Ghadiri T, Mobasseri M, Gholizadeh S, Beyer C, Sharifzadeh M (2011). "Effects of pentoxifylline and H-89 on epileptogenic activity of bucladesine in pentylenetetrazol-treated mice". European Journal of Pharmacology. 670 (2–3): 464–70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.026. PMID 21946102.

- ↑ Li W, Zheng L, Sheng C, Cheng X, Qing L, Qu S (2011). "Systematic review on the treatment of pentoxifylline in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease". Lipids in Health and Disease. 10: 49. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-10-49. PMC 3088890

. PMID 21477300.

. PMID 21477300. - ↑ El-Sakka, A. I. (2011). "Reversion of penile fibrosis: Current information and a new horizon". Arab Journal of Urology. 9 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.aju.2011.03.013. PMC 4149188

. PMID 26579268.

. PMID 26579268. - ↑ Anele, U. A.; Morrison, B. F.; Burnett, A. L. (2015). "Molecular pathophysiology of priapism: Emerging targets". Current drug targets. 16 (5): 474–83. PMC 4430197

. PMID 25392014.

. PMID 25392014.