Principle of least action

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Core topics |

- This article discusses the history of the principle of least action. For the application, please refer to action (physics).

The principle of least action – or, more accurately, the principle of stationary action – is a variational principle that, when applied to the action of a mechanical system, can be used to obtain the equations of motion for that system. In relativity, a different action must be minimized or maximized. The principle can be used to derive Newtonian, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian equations of motion, and even general relativity (see Einstein–Hilbert action). It was historically called "least" because its solution requires finding the path that has the least change from nearby paths.[1] Its classical mechanics and electromagnetic expressions are a consequence of quantum mechanics, but the stationary action method helped in the development of quantum mechanics.[2]

The principle remains central in modern physics and mathematics, being applied in thermodynamics,[3] fluid mechanics,[4] the theory of relativity, quantum mechanics,[5] particle physics, and string theory[6] and is a focus of modern mathematical investigation in Morse theory. Maupertuis' principle and Hamilton's principle exemplify the principle of stationary action.

The action principle is preceded by earlier ideas in surveying and optics. Rope stretchers in ancient Egypt stretched corded ropes to measure the distance between two points. Ptolemy, in his Geography (Bk 1, Ch 2), emphasized that one must correct for "deviations from a straight course". In ancient Greece, Euclid wrote in his Catoptrica that, for the path of light reflecting from a mirror, the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. Hero of Alexandria later showed that this path was the shortest length and least time.[7]

Scholars often credit Pierre Louis Maupertuis for formulating the principle of least action because he wrote about it in 1744[8] and 1746.[9] However, Leonhard Euler discussed the principle in 1744,[10] and evidence shows that Gottfried Leibniz preceded both by 39 years.[11][12][13]

In 1932, Paul Dirac discerned the quantum mechanical underpinning of the principle in the quantum interference of amplitudes: for macroscopic systems, the dominant contribution to the apparent path is the classical path (the stationary, action-extremizing one), while any other path is possible in the quantum realm.

General statement

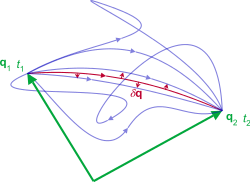

The starting point is the action, denoted (calligraphic S), of a physical system. It is defined as the integral of the Lagrangian L between two instants of time t1 and t2 - technically a functional of the N generalized coordinates q = (q1, q2 ... qN) which define the configuration of the system:

where the dot denotes the time derivative, and t is time.

Mathematically the principle is[15][16][17]

where δ (Greek lowercase delta) means a small change. In words this reads:[14]

- The path taken by the system between times t1 and t2 is the one for which the action is stationary (no change) to first order.

In applications the statement and definition of action are taken together:[18]

The action and Lagrangian both contain the dynamics of the system for all times. The term "path" simply refers to a curve traced out by the system in terms of the coordinates in the configuration space, i.e. the curve q(t), parameterized by time (see also parametric equation for this concept).

Origins, statements, and controversy

Fermat

In the 1600s, Pierre de Fermat postulated that "light travels between two given points along the path of shortest time," which is known as the principle of least time or Fermat's principle.[17]

Maupertuis

Credit for the formulation of the principle of least action is commonly given to Pierre Louis Maupertuis, who felt that "Nature is thrifty in all its actions", and applied the principle broadly:

The laws of movement and of rest deduced from this principle being precisely the same as those observed in nature, we can admire the application of it to all phenomena. The movement of animals, the vegetative growth of plants ... are only its consequences; and the spectacle of the universe becomes so much the grander, so much more beautiful, the worthier of its Author, when one knows that a small number of laws, most wisely established, suffice for all movements.— Pierre Louis Maupertuis[19]

This notion of Maupertuis, although somewhat deterministic today, does capture much of the essence of mechanics.

In application to physics, Maupertuis suggested that the quantity to be minimized was the product of the duration (time) of movement within a system by the "vis viva",

Maupertuis' principle

which is the integral of twice what we now call the kinetic energy T of the system.

Euler

Leonhard Euler gave a formulation of the action principle in 1744, in very recognizable terms, in the Additamentum 2 to his Methodus Inveniendi Lineas Curvas Maximi Minive Proprietate Gaudentes. Beginning with the second paragraph:

| “ | Let the mass of the projectile be M, and let its speed be v while being moved over an infinitesimal distance ds. The body will have a momentum Mv that, when multiplied by the distance ds, will give Mv ds, the momentum of the body integrated over the distance ds. Now I assert that the curve thus described by the body to be the curve (from among all other curves connecting the same endpoints) that minimizes

or, provided that M is constant along the path,

|

” | |

| — Leonhard Euler[10][20] | |||

As Euler states, ∫Mvds is the integral of the momentum over distance travelled, which, in modern notation, equals the reduced action

Euler's principle

Thus, Euler made an equivalent and (apparently) independent statement of the variational principle in the same year as Maupertuis, albeit slightly later. Curiously, Euler did not claim any priority, as the following episode shows.

Disputed priority

Maupertuis' priority was disputed in 1751 by the mathematician Samuel König, who claimed that it had been invented by Gottfried Leibniz in 1707. Although similar to many of Leibniz's arguments, the principle itself has not been documented in Leibniz's works. König himself showed a copy of a 1707 letter from Leibniz to Jacob Hermann with the principle, but the original letter has been lost. In contentious proceedings, König was accused of forgery,[11] and even the King of Prussia entered the debate, defending Maupertuis (the head of his Academy), while Voltaire defended König.

Euler, rather than claiming priority, was a staunch defender of Maupertuis, and Euler himself prosecuted König for forgery before the Berlin Academy on 13 April 1752.[11] The claims of forgery were re-examined 150 years later, and archival work by C.I. Gerhardt in 1898[12] and W. Kabitz in 1913[13] uncovered other copies of the letter, and three others cited by König, in the Bernoulli archives.

Further development

Euler continued to write on the topic; in his Reflexions sur quelques loix generales de la nature (1748), he called the quantity "effort". His expression corresponds to what we would now call potential energy, so that his statement of least action in statics is equivalent to the principle that a system of bodies at rest will adopt a configuration that minimizes total potential energy.

Lagrange and Hamilton

Much of the calculus of variations was stated by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1760[21][22] and he proceeded to apply this to problems in dynamics. In Méchanique Analytique (1788) Lagrange derived the general equations of motion of a mechanical body.[23] William Rowan Hamilton in 1834 and 1835[24] applied the variational principle to the classical Lagrangian function

to obtain the Euler–Lagrange equations in their present form.

Jacobi and Morse

In 1842, Carl Gustav Jacobi tackled the problem of whether the variational principle always found minima as opposed to other stationary points (maxima or stationary saddle points); most of his work focused on geodesics on two-dimensional surfaces.[25] The first clear general statements were given by Marston Morse in the 1920s and 1930s,[26] leading to what is now known as Morse theory. For example, Morse showed that the number of conjugate points in a trajectory equalled the number of negative eigenvalues in the second variation of the Lagrangian.

Gauss and Hertz

Other extremal principles of classical mechanics have been formulated, such as Gauss's principle of least constraint and its corollary, Hertz's principle of least curvature.

Disputes about possible teleological aspects

The mathematical equivalence of the differential equations of motion and their integral counterpart has important philosophical implications. The differential equations are statements about quantities localized to a single point in space or single moment of time. For example, Newton's second law

states that the instantaneous force F applied to a mass m produces an acceleration a at the same instant. By contrast, the action principle is not localized to a point; rather, it involves integrals over an interval of time and (for fields) an extended region of space. Moreover, in the usual formulation of classical action principles, the initial and final states of the system are fixed, e.g.,

- Given that the particle begins at position x1 at time t1 and ends at position x2 at time t2, the physical trajectory that connects these two endpoints is an extremum of the action integral.

In particular, the fixing of the final state has been interpreted as giving the action principle a teleological character which has been controversial historically. However, according to W. Yourgrau and S. Mandelstam, the teleological approach... presupposes that the variational principles themselves have mathematical characteristics which they de facto do not possess[27] In addition, some critics maintain this apparent teleology occurs because of the way in which the question was asked. By specifying some but not all aspects of both the initial and final conditions (the positions but not the velocities) we are making some inferences about the initial conditions from the final conditions, and it is this "backward" inference that can be seen as a teleological explanation. Teleology can also be overcome if we consider the classical description as a limiting case of the quantum formalism of path integration, in which stationary paths are obtained as a result of interference of amplitudes along all possible paths.

The short story Story of Your Life by the speculative fiction writer Ted Chiang contains visual depictions of Fermat's Principle along with a discussion of its teleological dimension. Keith Devlin's The Math Instinct contains a chapter, "Elvis the Welsh Corgi Who Can Do Calculus" that discusses the calculus "embedded" in some animals as they solve the "least time" problem in actual situations.

More Fundamental Than Newton's 2nd Law

According to Richard Feynman, the principle of least action is mathematically more specific than Newton's 2nd law and more fundamental in theoretical physics because it explains a wider range of physical law. You can derive Newton's 2nd law from least action, but the converse is not true without also applying Newton's 1st and 3rd laws and disallowing non-conservative forces like friction. By being more specific and thereby explaining only conservative forces, the principle of least action is able to solve problems Newton's 2nd law can't, but the converse is not true. The principle of least action can be used to derive the conservation of momentum and energy if its symmetry in space and time are assumed (see Noether's theorem).[2] It correctly does not allow non-conservative potential fields, but Newton's 2nd law allows for them by allowing for non-conservative momenta and forces (such as friction) which are not fundamental forces.[28] The mathematical basis for the difference is that Newton's 2nd law (stated as F=dp/dt instead of F=ma) allows for momentums p(t)=q(t)+C where q(t) are conserved momenta allowed by least action and C is a constant that can be non-zero in Newton's 2nd law but not in least action. The constant allows for non-conservative momenta and therefore non-conservative forces and potentials in Newton's 2nd law. Newton's 2nd law explains conservation of energy and momentum and can be used to show equivalency with least action when forces are properly conserved, e.g. when forces are summed to zero in accordance with Newton's 1st and 3rd laws and when accounting for heat generated by friction. Derivations of Lagrangian and Hamiltonian methods do not begin with Newton's 2nd law, but with a more modern mathematical formulation of it that requires forces to be conservative.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Chapter 19 of Volume II, Feynman R, Leighton R, and Sands M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics . 3 volumes 1964, 1966. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 63-20717. ISBN 0-201-02115-3 (1970 paperback three-volume set); ISBN 0-201-50064-7 (1989 commemorative hardcover three-volume set); ISBN 0-8053-9045-6 (2006 the definitive edition (2nd printing); hardcover)

- 1 2 "The Character of Physical Law" Richard Feynman

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003491608000602

- ↑ http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Principle_of_least_action

- ↑ "The principle of least action in quantum mechanics", RP Feynman - 1942

- ↑ http://www.damtp.cam.ac.uk/user/db275/LeastAction.pdf

- ↑ Kline, Morris (1972). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 167–68. ISBN 0-19-501496-0.

- ↑ P.L.M. de Maupertuis, Accord de différentes lois de la nature qui avaient jusqu'ici paru incompatibles. (1744) Mém. As. Sc. Paris p. 417. (English translation)

- ↑ P.L.M. de Maupertuis, Le lois de mouvement et du repos, déduites d'un principe de métaphysique. (1746) Mém. Ac. Berlin, p. 267.(English translation)

- 1 2 Leonhard Euler, Methodus Inveniendi Lineas Curvas Maximi Minive Proprietate Gaudentes. (1744) Bousquet, Lausanne & Geneva. 320 pages. Reprinted in Leonhardi Euleri Opera Omnia: Series I vol 24. (1952) C. Cartheodory (ed.) Orell Fuessli, Zurich. scanned copy of complete text at The Euler Archive, Dartmouth.

- 1 2 3 J J O'Connor and E F Robertson, "The Berlin Academy and forgery", (2003), at The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- 1 2 Gerhardt CI. (1898) "Über die vier Briefe von Leibniz, die Samuel König in dem Appel au public, Leide MDCCLIII, veröffentlicht hat", Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, I, 419-427.

- 1 2 Kabitz W. (1913) "Über eine in Gotha aufgefundene Abschrift des von S. König in seinem Streite mit Maupertuis und der Akademie veröffentlichten, seinerzeit für unecht erklärten Leibnizbriefes", Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, II, 632-638.

- 1 2 R. Penrose (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. p. 474. ISBN 0-679-77631-1.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- ↑ McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C.B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3

- 1 2 Analytical Mechanics, L.N. Hand, J.D. Finch, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-57572-0

- ↑ Classical Mechanics, T.W.B. Kibble, European Physics Series, McGraw-Hill (UK), 1973, ISBN 0-07-084018-0

- ↑ Chris Davis. Idle theory (1998)

- ↑ Euler, Additamentum II (external link), ibid. (English translation)

- ↑ D. J. Struik, ed. (1969). A Source Book in Mathematics, 1200-1800. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 406-413

- ↑ Kline, Morris (1972). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-501496-0. pp. 582-589

- ↑ Lagrange, Joseph-Louis (1788). Mécanique Analytique. p. 226

- ↑ W. R. Hamilton, "On a General Method in Dynamics", Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society Part I (1834) p.247-308; Part II (1835) p. 95-144. (From the collection Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1805-1865): Mathematical Papers edited by David R. Wilkins, School of Mathematics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland. (2000); also reviewed as On a General Method in Dynamics)

- ↑ G.C.J. Jacobi, Vorlesungen über Dynamik, gehalten an der Universität Königsberg im Wintersemester 1842-1843. A. Clebsch (ed.) (1866); Reimer; Berlin. 290 pages, available online Œuvres complètes volume 8 at Gallica-Math from the Gallica Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ↑ Marston Morse (1934). "The Calculus of Variations in the Large", American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publication 18; New York.

- ↑ Stöltzner, Michael (1994). Inside Versus Outside: Action Principles and Teleology. Springer. pp. 33–62. ISBN 978-3-642-48649-4.

- ↑ "The Principle of Least Action" Richard Feynman

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Principle of least action |

- Interactive explanation of the principle of least action

- Interactive applet to construct trajectories using principle of least action

- Georgi Yordanov Georgiev 2012 , A quantitative measure, mechanism and attractor for self-organization in networked complex systems, in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS 7166), F.A. Kuipers and P.E. Heegaard (Eds.): IFIP International Federation for Information Processing, Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Self-Organizing Systems (IWSOS 2012), pp. 90–95, Springer-Verlag (2012).

- Georgi Yordanov Georgiev and Iskren Yordanov Georgiev 2002 , The least action and the metric of an organized system, in Open Systems and Information Dynamics, 9(4), p. 371-380 (2002)