Trust law

| Wills, trusts and estates |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Wills |

|

Sections Property disposition |

| Trusts |

|

Common types Other types

Governing doctrines |

| Estate administration |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

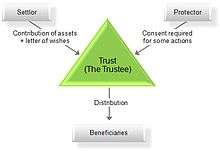

A trust is a relationship whereby property is held by one party for the benefit of another. A trust is created by a settlor, who transfers property to a trustee. The trustee holds that property for the trust's beneficiaries. Trusts exist mainly in common law jurisdictions and similar systems existed since Roman times.[1]

An owner of property that places property into trust turns over part of his or her bundle of rights to the trustee, separating the property's legal ownership and control from its equitable ownership and benefits. This may be done for tax avoidance reasons or to control the property and its benefits if the settlor is absent, incapacitated, or dead. Trusts are frequently created in wills, defining how money and property will be handled for children or other beneficiaries.

The trustee is given legal title to the trust property, but is obligated to act for the good of the beneficiaries. The trustee may be compensated and have expenses reimbursed, but otherwise must turn over all profits from the trust properties. Trustees who violate this fiduciary duty are self-dealing. Courts can reverse self-dealing actions, order profits returned, and impose other sanctions.

The trustee may be either an individual, a company, or a public body. There may be a single trustee or multiple co-trustees. The trust is governed by the terms under which it was created. In most jurisdictions, this requires a contractual trust agreement or deed.

Overview

A trust is created by a settlor, who transfers title to some or all of his or her property to a trustee, who then holds title to that property in trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries.[2] The trust is governed by the terms under which it was created. In most jurisdictions, this requires a contractual trust agreement or deed. It is possible for a single individual to assume the role of more than one of these parties, and for multiple individuals to share a single role. For example, in a living trust it is common for the grantor to be both a trustee and a lifetime beneficiary, while naming other contingent beneficiaries.

Trusts have existed since Roman times and have become one of the most important innovations in property law.[1] Trust law has evolved through court rulings differently in different states, so statements in this article are generalizations, understanding the jurisdiction-specific case law involved is tricky. Some U.S. States are adapting the Uniform Trust Code to codify and harmonize their trust laws, but state-specific variations still remain.

An owner placing property into trust turns over part of his or her bundle of rights to the trustee, separating the property's legal ownership and control from its equitable ownership and benefits. This may be done for tax reasons or to control the property and its benefits if the settlor is absent, incapacitated, or dead. Testamentary trusts may be created in wills, defining how money and property will be handled for children or other beneficiaries.

While the trustee is given legal title to the trust property, in accepting the property title, the trustee owes a number of fiduciary duties to the beneficiaries. The primary duties owed include the duty of loyalty, the duty of prudence, the duty of impartiality.[3] A trustee may be held to a very high standard of care in their dealings, in order to enforce their behavior. To ensure beneficiaries receive their due, trustees are subject to a number of ancillary duties in support of the primary duties, including a duties of openness and transparency; duties of recordkeeping, accounting, and disclosure. In addition, a trustee has a duty to know, understand, and abide by the terms of the trust and relevant law. The trustee may be compensated and have expenses reimbursed, but otherwise must turn over all profits from the trust properties.

There are strong restrictions regarding a trustee with conflict of interests. Courts can reverse a trustee's actions, order profits returned, and impose other sanctions if it finds a trustee has failed in any of their duties. Such a failure is termed a breach of trust, and can leave a neglectful or dishonest trustee with severe liabilities for their failures. It is highly advisable for both settlors and trustees to seek qualified legal counsel prior to entering into a trust agreement.

History

Ancient examples

Possibly the earliest concept, which later developed into what today is understood as a trust, related to land. An ancient king (settlor) grants property back to its previous owner (beneficiary) during his absence, supported by witness testimony (trustee). In essence and in this case, the king, in place of the later state (trustor and holder of assets at highest position) issues ownership along with past proceeds to the original beneficiary:

On the testimony of Gehazi the servant of Elisha that the woman was the owner of these lands, the king returns all her property to her. From the fact that the king orders his eunuch to return to the woman all her property and the produce of her land from the time that she left...[4]

Equity under the Common law

Roman law had a well-developed concept of the trust (fideicommissum) in terms of "testamentary trusts" created by wills but never developed the concept of the inter vivos (living) trusts which apply while the creator lives. This was created by later common law jurisdictions. Personal trust law developed in England at the time of the Crusades, during the 12th and 13th centuries. In medieval English trust law, the settlor was known as the feoffor to uses while the trustee was known as the feoffee to uses and the beneficiary was known as the cestui que use, or cestui que trust.

At the time, land ownership in England was based on the feudal system. When a landowner left England to fight in the Crusades, he conveyed ownership of his lands in his absence to manage the estate and pay and receive feudal dues, on the understanding that the ownership would be conveyed back on his return. However, Crusaders often encountered refusal to hand over the property upon their return. Unfortunately for the Crusader, English common law did not recognize his claim. As far as the King's courts were concerned, the land belonged to the trustee, who was under no obligation to return it. The Crusader had no legal claim. The disgruntled Crusader would then petition the king, who would refer the matter to his Lord Chancellor. The Lord Chancellor could decide a case according to his conscience. At this time, the principle of equity was born.

The Lord Chancellor would consider it "unconscionable" that the legal owner could go back on his word and deny the claims of the Crusader (the "true" owner). Therefore, he would find in favor of the returning Crusader. Over time, it became known that the Lord Chancellor's court (the Court of Chancery) would continually recognize the claim of a returning Crusader. The legal owner would hold the land for the benefit of the original owner, and would be compelled to convey it back to him when requested. The Crusader was the "beneficiary" and the acquaintance the "trustee". The term "use of land" was coined, and in time developed into what we now know as a trust.

Certain abuses solved by antitrust law

"Antitrust law" emerged in the 19th century when industries created monopolistic trusts by entrusting their shares to a board of trustees in exchange for shares of equal value with dividend rights; these boards could then enforce a monopoly. However, trusts were used in this case because a corporation could not own other companies' stock[5]:447 and thereby become a holding company without a "special act of the legislature".[6] Holding companies were used after the restriction on owning other companies' shares was lifted.[5]:447

Significance

The trust is widely considered to be the most innovative contribution of the English legal system.[7] Today, trusts play a significant role in most common law systems, and their success has led some civil law jurisdictions to incorporate trusts into their civil codes. In Curaçao, for example, the trust was enacted into law on 1 January 2012; however, the Curaçao Civil Code only allows express trusts constituted by notarial instrument.[8] France has recently added a similar, Roman-law-based device to its own law with the fiducie,[9] amended in 2009;[10] the fiducie, unlike a trust, is a contractual relationship. Trusts are widely used internationally, especially in countries within the English law sphere of influence, and whilst most civil law jurisdictions do not generally contain the concept of a trust within their legal systems, they do recognise the concept under the Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition (partly only the extent that they are parties thereto). The Hague Convention also regulates conflict of trusts.

Although trusts are often associated with intrafamily wealth transfers, they have become very important in American capital markets, particularly through pension funds (in certain countries essentially always trusts) and mutual funds (often trusts).[5]

Basic principles

Property of any sort may be held in a trust. The uses of trusts are many and varied, for both personal and commercial reasons, and trusts may provide benefits in estate planning, asset protection, and taxes. Living trusts may be created during a person's life (through the drafting of a trust instrument) or after death in a will.

In a relevant sense, a trust can be viewed as a generic form of a corporation where the settlors (investors) are also the beneficiaries. This is particularly evident in the Delaware business trust, which could theoretically, with the language in the "governing instrument", be organized as a cooperative corporation or a limited liability corporation,[5]:475–6 although traditionally the Massachusetts business trust has been commonly used in the US. One of the most significant aspects of trusts is the ability to partition and shield assets from the trustee, multiple beneficiaries, and their respective creditors (particularly the trustee's creditors), making it "bankruptcy remote", and leading to its use in pensions, mutual funds, and asset securitization[5] as well protection of individual spendthrifts through the spendthrift trust.

Terminology

- Appointer: This is the person who can appoint a new trustee or remove an existing one. This person is usually mentioned in the trust deed.

- Appointment: In trust law, "appointment" often has its everyday meaning. It is common to talk of "the appointment of a trustee", for example. However, "appointment" also has a technical trust law meaning, either:

- the act of appointing (i.e. giving) an asset from the trust to a beneficiary (usually where there is some choice in the matter—such as in a discretionary trust); or

- the name of the document which gives effect to the appointment.

- The trustee's right to do this, where it exists, is called a power of appointment. Sometimes, a power of appointment is given to someone other than the trustee, such as the settlor, the protector, or a beneficiary.

- As Trustee For (ATF): This is the legal term used to imply that an entity is acting as a trustee.

- Beneficiary: A beneficiary is anyone who receives benefits from any assets the trust owns.

- In Its Own Capacity (IIOC): This term refers to the fact that the trustee is acting on its own behalf.

- Protector: A protector may be appointed in an express, inter vivos trust, as a person who has some control over the trustee—usually including a power to dismiss the trustee and appoint another. The legal status of a protector is the subject of some debate. No-one doubts that a trustee has fiduciary responsibilities. If a protector also has fiduciary responsibilities then the courts—if asked by beneficiaries—could order him or her to act in the way the court decrees. However, a protector is unnecessary to the nature of a trust—many trusts can and do operate without one. Also, protectors are comparatively new, while the nature of trusts has been established over hundreds of years. It is therefore thought by some that protectors have fiduciary duties, and by others that they do not. The case law has not yet established this point.

- Settlor(s): This is the person (or persons) who creates the trust. Grantor(s) is a common synonym.

- Terms of the Trust means the settlor's wishes expressed in the Trust Instrument.

- Trust deed: A trust deed is a legal document that defines the trust such as the trustee, beneficiaries, settlor and appointer, and the terms and conditions of the agreement.

- Trust distributions: A trust distribution is any income or asset that is given out to the beneficiaries of the trust.

- Trustee: A person (either an individual, a corporation or more than one of either) who administers a trust. A trustee is considered a fiduciary and owes the highest duty under the law to protect trust assets from unreasonable loss for the trust's beneficiaries.

Creation

Trusts may be created by the expressed intentions of the settlor (express trusts)[11] or they may be created by operation of law known as implied trusts. An implied trust is one created by a court of equity because of acts or situations of the parties. Implied trusts are divided into two categories: resulting and constructive. A resulting trust is implied by the law to work out the presumed intentions of the parties, but it does not take into consideration their expressed intent. A constructive trust[12] is a trust implied by law to work out justice between the parties, regardless of their intentions.

Typically a trust can be created in the following ways:

- a written trust instrument created by the settlor and signed by both the settlor and the trustees (often referred to as an inter vivos or living trust);

- an oral declaration;[13]

- the will of a decedent, usually called a testamentary trust; or

- a court order (for example in family proceedings).

In some jurisdictions certain types of assets may not be the subject of a trust without a written document.[14]

Formalities

Generally, a trust requires three certainties, as determined in Knight v Knight:

- Intention. There must be a clear intention to create a trust[15](Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry)

- Subject Matter. The property subject to the trust must be clearly identified (Palmer v Simmonds). One may not, for example state, settle "the majority of my estate", as the precise extent cannot be ascertained. Trust property may be any form of specific property, be it real or personal, tangible or intangible. It is often, for example, real estate, shares or cash.

- Objects. The beneficiaries of the trust must be clearly identified,[16] or at least be ascertainable (Re Hain's Settlement). In the case of discretionary trusts, where the trustees have power to decide who the beneficiaries will be, the settlor must have described a clear class of beneficiaries (McPhail v Doulton). Beneficiaries may include people not born at the date of the trust (for example, "my future grandchildren"). Alternatively, the object of a trust could be a charitable purpose rather than specific beneficiaries.

Trustees

A trust may have multiple trustees, and these trustees are the legal owners of the trust's property, but have a fiduciary duty to beneficiaries and various duties, such as a duty of care and a duty to inform.[17] If trustees do not adhere to these duties, they may be removed through a legal action. The trustee may be either a person or a legal entity such as a company, but typically the trust itself is not an entity and any lawsuit must be against the trustees. A trustee has many rights and responsibilities which vary based on the jurisdiction and trust instrument. If a trust lacks a trustee, a court may appoint a trustee.

The trustees administer the affairs attendant to the trust. The trust's affairs may include prudently investing the assets of the trust, accounting for and reporting periodically to the beneficiaries, filing required tax returns, and other duties. In some cases dependent upon the trust instrument, the trustees must make discretionary decisions as to whether beneficiaries should receive trust assets for their benefit. A trustee may be held personally liable for problems, although fiduciary liability insurance similar to directors and officers liability insurance can be purchased. For example, a trustee could be liable if assets are not properly invested. However, in the United States, similar to directors and officers, an exculpatory clause may minimize liability; although this was previously held to be against public policy, this position has changed.[18]

In the United States, the Uniform Trust Code provides for reasonable compensation and reimbursement for trustees subject to review by courts,[19] although trustees may be unpaid. Commercial banks acting as trustees typically charge about 1% of assets under management.[20]

Beneficiaries

The beneficiaries are beneficial (or equitable) owners of the trust property. Either immediately or eventually, the beneficiaries will receive income from the trust property, or they will receive the property itself. The extent of a beneficiary's interest depends on the wording of the trust document. One beneficiary may be entitled to income (for example, interest from a bank account), whereas another may be entitled to the entirety of the trust property when he attains the age of twenty-five years. The settlor has much discretion when creating the trust, subject to some limitations imposed by law.

Purposes

Common purposes for trusts include:

- Privacy: Trusts may be created purely for privacy. The terms of a will are public in certain jurisdictions, while the terms of a trust are not.

- Spendthrift clauses: Trusts may be used to protect beneficiaries (for example, one's children) against their own inability to handle money. These are especially attractive for spendthrifts. Courts may generally recognize spendthrift clauses against trust beneficiaries and their creditors, but not against creditors of a settlor.

- Wills and estate planning: Trusts frequently appear in wills (indeed, technically, the administration of every deceased's estate is a form of trust). Conventional wills typically leave assets to the deceased's spouse (if any), and then to the children equally. If the children are under 18, or under some other age mentioned in the will (21 and 25 are common), a trust must come into existence until the contingency age is reached. The executor of the will is (usually) the trustee, and the children are the beneficiaries. The trustee will have powers to assist the beneficiaries during their minority.[21]

- Charities: In some common law jurisdictions all charities must take the form of trusts. In others, corporations may be charities also. In most jurisdictions, charities are tightly regulated for the public benefit (in England, for example, by the Charity Commission).

- Unit trusts: The trust has proved to be such a flexible concept that it has proved capable of working as an investment vehicle: the unit trust.

- Pension plans: Pension plans are typically set up as a trust, with the employer as settlor, and the employees and their dependents as beneficiaries.

- Remuneration trusts: Trusts for the benefit of directors and employees or companies or their families or dependents. This form of trust was developed by Paul Baxendale-Walker and has since gained widespread use.[22]

- Corporate structures: Complex business arrangements, most often in the finance and insurance sectors, sometimes use trusts among various other entities (e.g., corporations) in their structure.

- Asset protection: Trusts may allow beneficiaries to protect assets from creditors as the trust may be bankruptcy remote. For example, a discretionary trust, of which the settlor may be the protector and a beneficiary, but not the trustee and not the sole beneficiary. In such an arrangement the settlor may be in a position to benefit from the trust assets, without owning them, and therefore in theory protected from creditors. In addition, the trust may attempt to preserve anonymity with a completely unconnected name (e.g., "The Teddy Bear Trust"). These strategies are ethically and legally controversial.

- Tax planning: The tax consequences of doing anything using a trust are usually different from the tax consequences of achieving the same effect by another route (if, indeed, it would be possible to do so). In many cases, the tax consequences of using the trust are better than the alternative, and trusts are therefore frequently used for legal tax avoidance. For an example see the "nil-band discretionary trust", explained at Inheritance Tax (United Kingdom).

- Co-ownership: Ownership of property by more than one person is facilitated by a trust. In particular, ownership of a matrimonial home is commonly effected by a trust with both partners as beneficiaries and one, or both, owning the legal title as trustee.

- Construction law: In Canada[23] and Minnesota monies owed by employers to contractors or by contractors to subcontractors on construction projects must by law be held in trust. In the event of contractor insolvency, this makes it much more likely that subcontractors will be paid for work completed.

- Legal retainer- Lawyers in certain countries often require that a legal retainer be paid upfront and held in trust until such time as the legal work is performed and billed to the client, this serves as a minimum guarantee of remuneration should the client become insolvent. However, strict legal ethical codes apply to the use of legal retainer trusts.

Types

Alphabetic list of trust types

Trusts go by many different names, depending on the characteristics or the purpose of the trust. Because trusts often have multiple characteristics or purposes, a single trust might accurately be described in several ways. For example, a living trust is often an express trust, which is also a revocable trust, and might include an incentive trust, and so forth.

- Community land trust: A community land trust is a nonprofit corporation that develops and stewards affordable housing, community gardens, civic buildings, commercial spaces and other community assets on behalf of a community. “CLTs” balance the needs of individuals to access land and maintain security of tenure with a community’s need to maintain affordability, economic diversity and local access to essential services.

- Constructive trust: Unlike an express trust, a constructive trust is not created by an agreement between a settlor and the trustee. A constructive trust is imposed by the law as an "equitable remedy". This generally occurs due to some wrongdoing, where the wrongdoer has acquired legal title to some property and cannot in good conscience be allowed to benefit from it. A constructive trust is, essentially, a legal fiction. For example, a court of equity recognizing a plaintiff's request for the equitable remedy of a constructive trust may decide that a constructive trust has been created and simply order the person holding the assets to deliver them to the person who rightfully should have them. The constructive trustee is not necessarily the person who is guilty of the wrongdoing, and in practice it is often a bank or similar organization. The distinction may be finer than the preceding exposition in that there are also said to be two forms of constructive trust, the institutional constructive trust and the remedial constructive trust. The latter is an "equitable remedy" imposed by law being truly remedial; the former arising due to some defect in the transfer of property.

- Discretionary trust: In a discretionary trust, certainty of object is satisfied if it can be said that there is a criterion which a person must satisfy in order to be a beneficiary (i.e., whether there is a 'class' of beneficiaries, which a person can be said to belong to). In that way, persons who satisfy that criterion (who are members of that class) can enforce the trust. Re Baden’s Deed Trusts; McPhail v Doulton

- Directed trust: In these types, a directed trustee is directed by a number of other trust participants in implementing the trust's execution; these participants may include a distribution committee, trust protector, or investment advisor. The directed trustee's role is administrative which involves following investment instructions, holding legal title to the trust assets, providing fiduciary and tax accounting, coordinating trust participants and offering dispute resolution among the participants

- Dynasty trust (also known as a generation-skipping trust): A type of trust in which assets are passed down to the grantor's grandchildren, not the grantor's children. The children of the grantor never take title to the assets. This allows the grantor to avoid the estate taxes that would apply if the assets were transferred to his or her children first. Generation-skipping trusts can still be used to provide financial benefits to a grantor's children, however, because any income generated by the trust's assets can be made accessible to the grantor's children while still leaving the assets in trust for the grandchildren.

- Express trust: An express trust arises where a settlor deliberately and consciously decides to create a trust, over their assets, either now, or upon his or her later death. In these cases this will be achieved by signing a trust instrument, which will either be a will or a trust deed. Almost all trusts dealt with in the trust industry are of this type. They contrast with resulting and constructive trusts. The intention of the parties to create the trust must be shown clearly by their language or conduct. For an express trust to exist, there must be certainty to the objects of the trust and the trust property. In the USA Statute of Frauds provisions require express trusts to be evidenced in writing if the trust property is above a certain value, or is real estate.

- Fixed trust: In a fixed trust, the entitlement of the beneficiaries is fixed by the settlor. The trustee has little or no discretion. Common examples are:

- Grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT): GRAT is an irrevocable trust whereby a grantor transfers asset(s), as a gift, into a trust and receives an annual payment from the trust for a period of time specified in the trust instrument. At the end of the term, the financial property is transferred (tax-free) to the named beneficiaries. This trust is commonly used in the U.S. to facilitate large financial gifts that are not subject to a gift tax.

- Hybrid trust: A hybrid trust combines elements of both fixed and discretionary trusts. In a hybrid trust, the trustee must pay a certain amount of the trust property to each beneficiary fixed by the settlor. But the trustee has discretion as to how any remaining trust property, once these fixed amounts have been paid out, is to be paid to the beneficiaries.

- Implied trust: An implied trust, as distinct from an express trust, is created where some of the legal requirements for an express trust are not met, but an intention on behalf of the parties to create a trust can be presumed to exist. A resulting trust may be deemed to be present where a trust instrument is not properly drafted and a portion of the equitable title has not been provided for. In such a case, the law may raise a resulting trust for the benefit of the grantor (the creator of the trust). In other words, the grantor may be deemed to be a beneficiary of the portion of the equitable title that was not properly provided for in the trust document.

- Incentive trust: A trust that uses distributions from income or principal as an incentive to encourage or discourage certain behaviors on the part of the beneficiary. The term "incentive trust" is sometimes used to distinguish trusts that provide fixed conditions for access to trust funds from discretionary trusts that leave such decisions up to the trustee.

- Inter vivos trust (or living trust): A settlor who is living at the time the trust is established creates an inter vivos trust.

- Irrevocable trust: In contrast to a revocable trust, an irrevocable trust is one in which the terms of the trust cannot be amended or revised until the terms or purposes of the trust have been completed. Although in rare cases, a court may change the terms of the trust due to unexpected changes in circumstances that make the trust uneconomical or unwieldy to administer, under normal circumstances an irrevocable trust may not be changed by the trustee or the beneficiaries of the trust.

- Land Trust: A private, nonprofit organization that, as all or part of its mission, actively works to conserve land by undertaking or assisting in land or conservation easement acquisition, or by its stewardship of such land or easements; or an agreement whereby one party (the trustee) agrees to hold ownership of a piece of real property for the benefit of another party (the beneficiary).

- Offshore trust: Strictly speaking, an offshore trust is a trust which is resident in any jurisdiction other than that in which the settlor is resident. However, the term is more commonly used to describe a trust in one of the jurisdictions known as offshore financial centers or, colloquially, as tax havens. Offshore trusts are usually conceptually similar to onshore trusts in common law countries, but usually with legislative modifications to make them more commercially attractive by abolishing or modifying certain common law restrictions. By extension, "onshore trust" has come to mean any trust resident in a high-tax jurisdiction.

- Personal injury trust: A personal injury trust is any form of trust where funds are held by trustees for the benefit of a person who has suffered an injury and funded exclusively by funds derived from payments made in consequence of that injury.

- Private and public trusts: A private trust has one or more particular individuals as its beneficiary. By contrast, a public trust (also called a charitable trust) has some charitable end as its beneficiary. In order to qualify as a charitable trust, the trust must have as its object certain purposes such as alleviating poverty, providing education, carrying out some religious purpose, etc. The permissible objects are generally set out in legislation, but objects not explicitly set out may also be an object of a charitable trust, by analogy. Charitable trusts are entitled to special treatment under the law of trusts and also the law of taxation.

- Protective trust: Here the terminology is different between the UK and the USA:

- In the UK, a protective trust is a life interest that terminates upon the happening of a specified event; such as the bankruptcy of the beneficiary, or any attempt by an individual to dispose of his or her interest. They have become comparatively rare.

- In the USA, a protective trust is a type of trust that was devised for use in estate planning. (In another jurisdiction this might be thought of as one type of asset protection trust.) Often a person, A, wishes to leave property to another person B. A, however, fears that the property might be claimed by creditors before A dies, and that therefore B would receive none of it. A could establish a trust with B as the beneficiary, but then A would not be entitled to use of the property before they died. Protective trusts were developed as a solution to this situation. A would establish a trust with both A and B as beneficiaries, with the trustee instructed to allow A use of the property until they died, and thereafter to allow its use to B. The property is then safe from being claimed by A's creditors, at least so long as the debt was entered into after the trust's establishment. This use of trusts is similar to life estates and remainders, and is frequently used as an alternative to them.

- Purpose trust: Or, more accurately, non-charitable purpose trust (all charitable trusts are purpose trusts). Generally, the law does not permit non-charitable purpose trusts outside of certain anomalous exceptions which arose under the eighteenth century common law (and, arguable, Quistclose trusts). Certain jurisdictions (principally, offshore jurisdictions) have enacted legislation validating non-charitable purpose trusts generally.

- QTIP Trust: Short for "qualified terminal interest property." A trust recognized under the tax laws of the United States which qualifies for the marital gift exclusion from the estate tax.

- Resulting trust: A resulting trust is a form of implied trust which occurs where (1) a trust fails, wholly or in part, as a result of which the settlor becomes entitled to the assets; or (2) a voluntary payment is made by A to B in circumstances which do not suggest gifting. B becomes the resulting trustee of A's payment.

- Revocable trust: A trust of this kind may be amended, altered or revoked by its settlor at any time, provided the settlor is not mentally incapacitated. Revocable trusts are becoming increasingly common in the US as a substitute for a will to minimize administrative costs associated with probate and to provide centralized administration of a person's final affairs after death.

- Secret trust: A post mortem trust constituted externally from a will but imposing obligations as a trustee on one, or more, legatees of a will.

- Semi-secret trust: A trust in which a will demonstrates the intention to create a trust, names a trustee, but does not identify the intended beneficiary.[24]

- Simple trust:

- In the US jurisdiction this has two distinct meanings:

- In a simple trust the trustee has no active duty beyond conveying the property to the beneficiary at some future time determined by the trust. This is also called a bare trust. All other trusts are special trusts where the trustee has active duties beyond this.

- A simple trust in Federal income tax law is one in which, under the terms of the trust document, all net income must be distributed on an annual basis.

- In the UK a bare or simple trust is one where the beneficiary has an immediate and absolute right to both the capital and income held in the trust. Bare trusts are commonly used to transfer assets to minors. Trustees hold the assets on trust until the beneficiary is 18 in England and Wales, or 16 in Scotland.[25]

- In the US jurisdiction this has two distinct meanings:

- Special trust: In the US, a special trust, also called complex trust, contrasts with a simple trust (see above). It does not require the income be paid out within the subject tax year. The funds from a complex trust can also be used to donate to a charity or for charitable purposes.

- Special Power of Appointment trust (SPA Trust): A trust implementing a special power of appointment to provide asset protection features.

- Spendthrift trust: It is a trust put into place for the benefit of a person who is unable to control their spending. It gives the trustee the power to decide how the trust funds may be spent for the benefit of the beneficiary.

- Standby Trust (or Pourover Trust): The trust is empty at creation during life and the will transfers the property into the trust at death. This is a statutory trust.

- Testamentary trust (or Will Trust): A trust created in an individual's will is called a testamentary trust. Because a will can become effective only upon death, a testamentary trust is generally created at or following the date of the settlor's death.

- Unit trust: A trust where the beneficiaries (called unitholders) each possess a certain share (called units) and can direct the trustee to pay money to them out of the trust property according to the number of units they possess. A unit trust is a vehicle for collective investment, rather than disposition, as the person who gives the property to the trustee is also the beneficiary.[26]

Regional variations

Trusts originated in England, and therefore English trusts law has had a significant influence, particularly among common law legal systems such as the United States and the countries of the Commonwealth.

Trust law in civil law jurisdictions, generally including Continental Europe only exists in a limited number of jurisdictions (e.g. Curaçao, Liechtenstein and Sint Maarten). The trust may however be recognized as an instrument of foreign law in conflict of laws cases, for example within the Brussels regime (Europe) and the parties to the Hague Trust Convention. Tax avoidance concerns have historically been one of the reasons that European countries with a civil law system have been reluctant to adopt trusts.[5]

United States

State law applies to trusts, and the Uniform Trust Code has been enacted by the legislatures in many states. In addition, federal law considerations such as federal taxes administered by the Internal Revenue Service may affect the structure and creation of trusts. The common law of trusts is summarized in the Restatements of the Law, such as the Restatement of Trusts, Third (2003−08).

In the United States the tax law allows trusts to be taxed as corporations, partnerships, or not at all depending on the circumstances, although trusts may be used for tax avoidance in certain situations.[5]:478 For example, the trust-preferred security is a hybrid (debt and equity) security with favorable tax treatment which is treated as regulatory capital on banks' balance sheets. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act changed this somewhat by not allowing these assets to be a part of (large) banks' regulatory capital.[27]:23

Estate planning

Living trusts, as opposed to testamentary (will) trusts, avoid probate.[28] Avoiding probate may save costs and maintain privacy[29] and living trusts have become very popular.[30] The probate courts may charge a fee based on a percentage net worth of the deceased time, and probate records are available to the public while distribution through a trust is private. Both living trusts and wills can also be used to plan for unforeseen circumstances such as incapacity or disability, by giving discretionary powers to the trustee or executor of the will.

Negative aspects of using a living trust as opposed to a will and probate include upfront legal expenses, the expense of trust administration, and a lack of certain safeguards. The cost of the trust may be 1% of the estate per year versus the one-time lump-sum fee of 1 to 4% for probate, which applies whether or not there is a drafted will. Unlike trusts, wills must be signed by two to three witnesses, the number depending on state law. Legal protections which apply to probate and not trusts include provisions which protect the decedent's assets from mismanagement or embezzlement, such as requirements of bonding, insurance, and itemized accountings of probate assets.

Estate tax effect

Living trusts generally do not shelter assets from the U.S. federal estate tax. Married couples may, however, effectively double the estate tax exemption amount by setting up the trust with a formula clause.[31]

For a living trust, the grantor may retain some level of control to the trust, such by appointment as protector under the trust instrument. Living trusts also, in practical terms, tend to be driven to large extent by tax considerations. If a living trust fails, the property will usually be held for the grantor/settlor on resulting trusts, which in some notable cases, has had catastrophic tax consequences.

South Africa

In many ways trusts in South Africa operate similarly to other common law countries, although the law of South Africa is actually a hybrid of the British common law system and Roman-Dutch law.

In South Africa, in addition to the traditional living trusts and will trusts there is a ‘bewind trust’ (inherited from the Roman-Dutch bewind administered by a bewindhebber)[32] in which the beneficiaries own the trust assets while the trustee administers the trust, although this is regarded by modern Dutch law as not actually a trust.[33] Bewind trusts are created as trading vehicles providing trustees with limited liability and certain tax advantages.

In South Africa, minor children cannot inherit assets and in the absence of a trust and assets held in a state institution, the Guardian's Fund, and released to the children in adulthood. Therefore, testamentary (will) trusts often leave assets in a trust for the benefit of these minor children.

There are two types of living trusts in South Africa, namely vested trusts and discretionary trusts. In vested trusts, the benefits of the beneficiaries are set out in the trust deed, whereas in discretionary trusts the trustees have full discretion at all times as to how much and when each beneficiary is to benefit.

Asset protection

Until recently, there were tax advantages to living trusts in South Africa, although most of these advantages have been removed. Protection of assets from creditors is a modern advantage. With notable exceptions, assets held by the trust are not owned by the trustees or the beneficiaries, the creditors of trustees or beneficiaries can have no claim against the trust. Under the Insolvency Act (Act 24 of 1936), assets transferred into a living trust remain at risk from external creditors for 6 months if the previous owner of the assets is solvent at the time of transfer, or 24 months if he/she is insolvent at the time of transfer. After 24 months, creditors have no claim against assets in the trust, although they can attempt to attach the loan account, thereby forcing the trust to sell its assets. Assets can be transferred into the living trust by selling it to the trust (through a loan granted to the trust) or donating cash to it (any natural person can donate R100 000 per year without attracting donations tax; 20% donations tax applies to further donations within the same tax year).

Tax considerations

Under South African law living trusts are considered tax payers. Two types of tax apply to living trusts, namely income tax and capital gains tax (CGT). A trust pays income tax at a flat rate of 40% (individuals pay according to income scales, usually less than 20%). The trust's income can, however, be taxed in the hands of either the trust or the beneficiary. A trust pays CGT at the rate of 20% (individuals pay 10%). Trusts do not pay deceased estate tax (although trusts may be required to pay back outstanding loans to a deceased estate, in which the loan amounts are taxable with deceased estate tax).[34]

The taxpayer whose residence has been ‘locked’ into a trust has now been given another opportunity to take advantage of these CGT exemptions. The Taxation Law Amendment Act of 30 September 2009 commenced on 1 January 2010 and granted a 2-year window period from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2011, affording a natural person the opportunity to take transfer of the residence with advantage of no transfer duty being payable or CGT consequences. Whilst taxpayers can take advantage of this opening of a window of opportunity, it is not likely that it will ever become available thereafter.[35]

See also

- Blind trust

- Foundation (charity)

- Knight v Knight

- Rabbi trust

- STEP (Society of Trust and Estate Practitioners), the international professional association for the trust industry

- Totten trust

- Trusts & Estates (journal)

Jurisdiction specific:

- Argentinian law number 24.441 of 1994.

- Australian trust law

- Henson trust

- Italian trust law

- Trust law in Civil law jurisdictions

- Trust law in England and Wales

Notes

- 1 2 Scott, Austin. "Importance of the Trust". U. Colo. L. Rev. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

The greatest and most distinctive achievement performed by Englishmen in the field of jurisprudence is the development from century to century of the trust idea.

- ↑ Restatment of Trusts (Third ed.). Section 2: American Law Institute. p. 17.

- ↑ Restatment of Trusts (Third ed.). Chapter 15: American Law Institute. p. 67.

- ↑ Ben-Barak, Zafrira. "Meribaal and the System of Land Grants in Ancient Israel." Biblica (1981): 73-91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hansmann, Henry; Mattei, Ugo (May 1998). "The Functions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis" (PDF). New York University Law Review. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Chandler, Jr., Alfred D. (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Harvard University Press. pp. 319–20.

- ↑ Roy Goode, Commercial Law (2nd ed.)

- ↑ M. Bergervoet and D.S. Mansur (14 April 2012). "De Curaçaose trust in de partijk" (PDF). Weekblad voor Privaatrecht, Notariaat en Registratie (in Dutch).

- ↑ "Loi n°2007-211 du 19 février 2007 instituant la fiducie". Legifrance.gouv.fr, le service public de la diffusion du droit. 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "Ordonnance n°2009-79 du 22 janvier 2009 (consolidated version)". Legifrance.gouv.fr, le service public de la diffusion du droit. 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "Database Access - UNSW Library".

- ↑ "Bahr v Nicolay (No 2) [1988] HCA 16; (1988) 164 CLR 604 (15 June 1988)".

- ↑ See for example T Choithram International SA and others v Pagarani and others [2001] 2 All ER 492

- ↑ For example, in England, trusts over land must be evidenced in writing under s.56 of the Law of Property Act 1925

- ↑ "Barclays Bank v Quistclose Investments Ltd [1968] UKHL 4 (31 October 1968)".

- ↑ "Re Baden (No 1) McPhail v Doulton [1970] UKHL 1 (06 May 1970)".

- ↑ Edward Jones Trust Company. Fundamental Duties of a Trustee: A Guide for Trustees in a post-Uniform Trust Code World.

- ↑ Last Beneficiary Standing: Identifying the Proper Parties in Breach of Fiduciary Cases. American Bar Association, Section of Real Property, Trust, & Estate Law. 20th Annual Real Property & Estate Planning Symposia.

- ↑ Trust Code Summary. Uniform Law Commission.

- ↑ Schanzenbach MM, Sitkoff RF. (2007). Did Reform of Prudent Trust Investment Laws Change Trust Portfolio Allocation?. Harvard Law School John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics and Business Discussion Paper Series. Paper 580.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Scott D. (2009–2010). "Frequently Asked Questions".

- ↑ Paul BW Chaplin#Biography

- ↑ Kirsh, Harvey J; Roth, Lori A (1 September 1997). "Construction law: Breach of trust in the construction industry". International Finance Law Review (IFLR).

- ↑ Julius B. Levine & Randall L. Holton, Enforcement of Secret and Semi-Secret Trusts, 5 Prob. L.J. 7, 16 (1983)

- ↑ "Bare trusts". HM Revenue & Customs. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Kam Fan Sin, The Legal Nature of the Unit Trust, Clarendon Press, 1998.

- ↑ "The Dodd-Frank Act: Commentary and Insights" (PDF). Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP & Affiliates. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Hannibal BS. (Testamentary Trusts: A testamentary trust goes into effect after the death of the trust maker. Nolo.

- ↑ Frequently asked questions about estate planning and probate. Francis, Orr, & Totusek LLP.

- ↑ American Bar Association. Ch.5 Living Trusts. Appears to be online copy of: The American Bar Association guide to wills and estates (1995). See also Ch. 4, Trusts.

- ↑ The formula clause may be: "I leave to my child the maximum allowable amount that is not subject to federal estate tax, with the remainder going to my wife." As of 2013, transfers to spouses are exempt from estate tax. See: After The Fiscal Cliff Deal: Estate And Gift Tax Explained. Forbes.

- ↑ Trust Overview. Moore Stephens Chartered Accountants.

- ↑ Oakley JA. (1996). Trends in Contemporary Trust Law, p. 108.

- ↑ E-book: Trusts for Business Owners, by Peter Carruthers and Robert Velosa.

- ↑ Miller, Winston E. (18 December 2009). "Dump That Trust Through The Window: Family Trust Tax Window". Winston Miller Attorneys.

References

- Hudson, A (2003). Equity and Trusts (3rd ed.). Cavendish Publishing. ISBN 1-85941-729-9.

- Mitchell, Charles; Hayton, DJ (2005). Hayton and Marshall's Commentary and Cases on the Law of Trusts and Equitable Remedies (12th ed.). Sweet & Maxwell.

- Mitchell, Charles; Hayton, DJ; Matthews, P (2006). Underhill and Hayton's Law Relating to Trusts and Trustees (17th ed.). Butterworths.

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Trust law. |

- Trust Law of the People's Republic of China (Order of the President No. 50) (PDF), Studio legale Tedioli, 28 April 2001