Tupelo, Mississippi

| Tupelo, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| City of Tupelo | |

|

Main Street in Tupelo | |

Location of Tupelo in Lee County | |

Tupelo, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°15′35″N 88°43′33″W / 34.25972°N 88.72583°WCoordinates: 34°15′35″N 88°43′33″W / 34.25972°N 88.72583°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| County | Lee |

| Incorporated | 1870 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Jason Shelton (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 133.2 km2 (51.4 sq mi) |

| • Land | 132.4 km2 (51.1 sq mi) |

| • Water | 0.8 km2 (0.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 85 m (279 ft) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • City | 34,546 |

| • Estimate (2014)[2] | 35,688 |

| • Density | 274/km2 (709/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 139,671 (US: 8th) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP codes | 38801–38804 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-74840 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0678931 |

| Website | City of Tupelo |

Tupelo /ˈtuːpəloʊ/ is the county seat and the largest city of Lee County, Mississippi. The seventh-largest city in the state, it is situated in Northeast Mississippi, between Memphis, Tennessee, and Birmingham, Alabama. It is accessed by Interstate 22. As of the 2010 census, the population was 34,546, with the surrounding counties of Lee, Pontotoc and Itawamba supporting a population of 139,671

Tupelo was the first city to gain an electrical power grid under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's program of the Tennessee Valley Authority construction of facilities during the Great Depression. The city is also the birthplace of singer Elvis Presley.[3]

History

European colonization

Indigenous peoples lived in the area for thousands of years. The historic Chickasaw and Choctaw, both Muskogean-speaking peoples of the Southeast, occupied this area long before European encounter.

French and British colonists traded with these indigenous peoples and tried to make alliances with them. The French established towns in Mississippi mostly on the Gulf Coast. At times, the European powers came into armed conflict. On May 26, 1736 the Battle of Ackia was fought near the site of the present Tupelo; British and Chickasaw soldiers repelled a French and Choctaw attack on the then-Chickasaw village of Ackia. The French, under Louisiana governor Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, had sought to link Louisiana with Acadia and the other northern colonies of New France.

In the early 19th century, after years of trading and encroachment by European-American settlers from the United States, conflicts increased as the US settlers tried to gain land from these nations. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and authorized the relocation of all the Southeast Native Americans west of the Mississippi River, which was completed by the end of the 1830s.

In the early years of settlement, European-Americans named this town Gum Pond, supposedly due to its numerous tupelo trees, known locally as blackgum. The city still hosts the annual Gumtree Arts Festival.

Civil War and post-war development

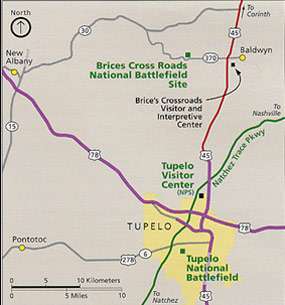

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate forces fought in the area in 1864 in the Battle of Tupelo. Designated the Tupelo National Battlefield, the war site is administered by the National Park Service (NPS). In addition, the Brices Cross Roads National Battlefield, about ten miles north, commemorates another Civil War site.

After the war, a cross-state railroad for northern Mississippi was constructed through the town, which encouraged industry and growth. With expansion, the town changed its name to Tupelo, in honor of the battle. It was incorporated in 1870.[4]

20th century to present

.jpg)

By the early twentieth century, the town had become a site of cotton textile mills, which provided new jobs for residents of the rural area. Under the state's segregation practices, the mills employed only white adults and children. Reformers documented the child workers and attempted to protect them through labor laws.[5]

The last known bank robbery by Machine Gun Kelly, a Prohibition-era gangster, took place on November 30, 1932 at the Citizen’s State Bank in Tupelo; his gang netted $38,000. After the robbery, the bank’s chief teller said of Kelly, “He was the kind of guy that, if you looked at him, you would never thought he was a bank robber.”[6]

During the Great Depression, Tupelo was electrified by the new Tennessee Valley Authority, which had constructed dams and power plants throughout the region to generate hydroelectric power for the large, rural area. The distribution infrastructure was built with federal assistance as well, employing many local workers. In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt visited this "First TVA City".

In 2007, the nearby village of Blue Springs was selected as the site for Toyota's eleventh automobile manufacturing plant in the United States.

In 2013 Gale Stauffer of the Tupelo Police Department died in a shootout following a bank robbery, possibly the first officer killed in the line of duty in the Department's history.[7]

Severe weather

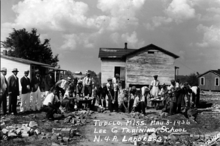

The spring of 1936 brought Tupelo one of its worst-ever natural disasters, part of the Tupelo-Gainesville tornado outbreak of April 5–6 in that year.[8] The storm leveled 48 city blocks and over 200 homes, killing 216 people and injuring more than 700 persons.[9] It struck at night, destroying large residential areas on the city's north side. Among the survivors was Elvis Presley, then a baby. Obliterating the Gum Pond neighborhood, the tornado dropped most of the victims' bodies in the pond. The storm has since been rated F5 on the modern Fujita scale.[10] The Tupelo Tornado is recognized as one of the deadliest in U.S. history.[11]

The Mississippi State Geologist estimated a final death toll of 233 persons, but 100 whites were still reported as hospitalized at the time. Because the white newspapers did not publish news about blacks until the 1940s and 1950s, historians have had difficulty learning the fates of blacks injured in the tornado. Based on this, historians now estimate the death toll was higher than in official records.[9][12] Fire broke out at the segregated Lee County Training School, which was destroyed. Its bricks were salvaged for other uses.

The area is subject to tornadoes. In 2008 one rated an EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale struck the town. On April 28, 2014, a large tornado struck Tupelo and the surrounding communities, causing significant damage.

Geography and climate

Tupelo is located in northeast Mississippi, north of Columbus, on future Interstate 22 and U.S. Route 78, midway between Memphis, Tennessee (northwest) and Birmingham, Alabama (southeast).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 51.4 square miles (133 km2), of which 51.1 square miles (132 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.78 km2) (0.62%) is water.

Tupelo has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification). Winters are short but cool, with sometimes-dramatic temperature swings. The warmest winter days can have high temperatures from 70 to near 80 F. and low temperatures from 50 to 60 degrees F. The coldest winter days usually have high temperatures below freezing (32 F.), and on rare occasions in the 20s F., with low temperatures near or below 12 degrees F. and occasional lows in the single digits F. or (rarely) lower still. In January, the coldest month, Tupelo's average high temperature is near 50 degrees F. and the average low about 30 degrees F. Day-to-day temperature variations are far less in the consistently hot and humid summer months. July and August high temperatures average near 90 degrees F., with low temperatures near 70 degrees F., with consistently high humidity and occasional thunderstorms, decreasing in frequency and intensity after June. The spring and fall months have generally pleasant temperatures, with average daily highs in the 70s F. in April and October, but with shower and thunderstorm activity markedly more frequent, intense and severe from March to May, when severe thunderstorms and occasional tornadoes are significant threats.

Tupelo has an average annual precipitation of over 55 inches per year - virtually the highest found anywhere in the eastern U.S. outside isolated highland areas and the immediate Gulf Coast (i.e. New Orleans, LA and Pensacola, FL areas), with its heavier summer-season rainfalls. Tupelo's average annual precipitation cycle demonstrates an unusual pattern for humid-subtropical climates worldwide. Many humid-subtropical areas (like the Shanghai, China area and the U.S. southeast Atlantic coast, i.e. Norfolk, VA; Cape Hatteras, NC; Charleston, SC; Savannah, GA) have highest monthly average precipitation amounts in July or August. In contrast, Tupelo has a prolonged "wetter season" from November to June, and a marked tendency toward drier conditions from late July through October. In terms of average monthly precipitation, Tupelo's single wettest month is March, averaging 6.3 inches, with December a close second at 6.1 inches (for both, virtually the highest average found anywhere in the United States outside windward West Coast areas and spotty highland areas). Spring (March to May) and to a lesser extent late fall/early winter (November-December) can be especially turbulent, with heavy-rain events and strong to occasionally violent showers and thunderstorms not uncommon. Tupelo lies near the heart of Dixie Alley, an area of the U.S. mid-South with a relatively high frequency of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. As elsewhere in Dixie Alley, the primary severe-weather season in Tupelo begins in late February, continuing into May, with a secondary "severe weather" peak in November–December. For example, Tupelo was hit hard by tornadoes in April 1936, and again in April 2014 (see "Severe Weather" section, above).

| Climate data for Tupelo, Mississippi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

84 (29) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

100 (38) |

108 (42) |

109 (43) |

108 (42) |

104 (40) |

96 (36) |

87 (31) |

81 (27) |

109 (43) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 50 (10) |

56 (13) |

65 (18) |

74 (23) |

81 (27) |

88 (31) |

91 (33) |

90 (32) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

63 (17) |

54 (12) |

72.7 (22.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

41 (5) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

70 (21) |

68 (20) |

62 (17) |

49 (9) |

40 (4) |

33 (1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−3 (−19) |

7 (−14) |

23 (−5) |

30 (−1) |

43 (6) |

50 (10) |

51 (11) |

38 (3) |

24 (−4) |

8 (−13) |

−3 (−19) |

−14 (−26) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 5.14 (130.6) |

4.68 (118.9) |

6.30 (160) |

4.94 (125.5) |

5.80 (147.3) |

4.82 (122.4) |

3.65 (92.7) |

2.67 (67.8) |

3.35 (85.1) |

3.38 (85.9) |

5.01 (127.3) |

6.12 (155.4) |

55.86 (1,418.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.3 (3.3) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.3 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.3 (0.8) |

2.8 (7.1) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 48.5 | 73.5 | 71.5 | 70.0 | 71.5 | 74.0 | 75.0 | 76.5 | 75.5 | 74.5 | 71.5 | 72.5 | 76.5 |

| Source #1: [13] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: [14] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 618 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,008 | 63.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,477 | 46.5% | |

| 1900 | 2,118 | 43.4% | |

| 1910 | 3,881 | 83.2% | |

| 1920 | 5,055 | 30.2% | |

| 1930 | 6,361 | 25.8% | |

| 1940 | 8,212 | 29.1% | |

| 1950 | 11,527 | 40.4% | |

| 1960 | 17,221 | 49.4% | |

| 1970 | 20,471 | 18.9% | |

| 1980 | 23,905 | 16.8% | |

| 1990 | 30,685 | 28.4% | |

| 2000 | 34,211 | 11.5% | |

| 2010 | 34,546 | 1.0% | |

| Est. 2015 | 35,680 | [15] | 3.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] 2013 Estimate[2] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there are 35,456 people, 13,602 households, and 8,965 families residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city is 58.7% White, 36.8% African American, 0.1% Native American, 1.0% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 2.0% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. 3.5% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race.[1]

According to the 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, there are 13,395 households, 42.8% are married couples living together, 2.6% have a male householder with no wife present, and 22.5% have a female householder with no husband present. 32.2% are non-family households, with 28.4% have a householder living alone and 3.8% having a householder not living alone. In addition, 39.7% of householders are living with related children under 18 and 60.3% with no related children under 18.[17] The average household size is 2.47 and the average family size is 3.08.[1]

The median income for a household in the city is $39,415. The poverty rate for people living below the poverty line is 20%.[1]

Economy

Historically, Tupelo served as a regional transportation hub, primarily due to its location at a railroad intersection. More recently, it has developed as strong tourism and hospitality sector based around the Elvis Presley birthplace and Natchez Trace. The city has also been successful at attracting manufacturing, retail and distribution operations (see 'Industry' section below).[18]

Industry

- Tupelo is the headquarters of the North Mississippi Medical Center, the largest non-metropolitan hospital in the United States. It serves people in North Mississippi, northwest Alabama and portions of Tennessee. The medical center was a winner of the prestigious Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in 2006 and 2012.

- The headquarters of two banking institutions are located here: BancorpSouth, with approximately $11.8 billion in assets (2006), and Renasant, with assets of approximately $4.2 billion (2011).

- The city is a five-time "All-America City Award" winner.

- It has a large furniture manufacturing industry. The journalist Dennis Seid noted that furniture manufacturing in Northeast Mississippi, "provid[ed] some 22,000 jobs, or almost 13% of the region's employment... with a $732 million annual payroll... producing $2.25 billion worth of goods."[19]

- Tecumseh, Heritage Home Group, Hancock Fabrics, Inc., Magnolia Fabrics, Toyota Motor Manufacturing Mississippi, H.M. Richards, JESCO Construction, MTD Products, Savings Oil Company (Dodge's Stores), and Cooper Tire & Rubber Company all operate or are headquartered in Tupelo and Lee County.

Arts and culture

- The Tupelo Buffalo Park and Zoo is home to hundreds of animals and a large American bison herd.

- It is the headquarters of the historic Natchez Trace Parkway, which connects Natchez, Mississippi, to Nashville, Tennessee. The parkway follows the route of the ancient Natchez Trace trail, a path used by indigenous peoples long before the Europeans came to the area.[20]

- Nearby are the Pharr Mounds, an important Middle Woodland period complex of nearly 2000-year-old burial earthworks, dating from 1 to 200 AD.[21]

- Civil War sites include Tupelo and Brices Cross Roads national battlefields.

- The Tupelo Automobile Museum is one of the largest of this type in North America.[20] In 2003, it was designated as the official automobile museum of the state. It houses more than 150 rare automobiles, all from the personal collection of Frank K. Spain, who founded the channel WTVA.

- Since its founding in 1969, the Tupelo Community Theatre has produced more than 200 works. In 2001 and 2004, it won awards at the Mississippi Theatre Association's Community Theatre festival. In 2004 its production of Bel Canto won at the Southeastern Theatre Conference. TCT's home is the historic Lyric Theatre, built in 1912.[22]

- The Tupelo Symphony Orchestra's season runs from September–April with concerts held at the Tupelo Civic Auditorium.[3] The symphony's free annual July 4 outdoor concert at Ballard Park draws thousands of fans.

- In 2005, the Rotary Club sponsored a commission for a statue to honor Chief Piomingo, a leader of the Chickasaw people who had occupied this area. It was erected in front of the new Tupelo City Hall.

- The Oren Dunn City Museum tells the Story of Community Building through permanent exhibits and a collection of historic structures. The Special Exhibit Gallery provides a venue for a variety of traveling and temporary shows throughout the year.

- In June 1956 noted singer Elvis Presley returned to Tupelo for a concert at the Mississippi-Alabama State Fair & Dairy Show. This event was recreated at the eighth "Elvis Presley Festival" in Tupelo on June 3, 2006. The fairgrounds is part of Tupelo's Fairpark District. The documentary film, The Homecoming: Tupelo Welcomes Elvis Home, premiered at the 2006 festival.

- The Lee County Library has an annual lecture series featuring nationally known authors.

- Built in 1937, the Church Street Elementary School (for white students in the segregated system) was hailed as one of the most outstanding designs of its time. A scale model of this Art Moderne structure, described as "the ideal elementary school," was displayed at the 1939 New York World's Fair.

- The BancorpSouth Arena opened in 1993 and is a venue for large events.[3]

- The Rap Group Rae Sremmurd comes from the city

Government

Tupelo's current mayor is Jason L. Shelton. The Tupelo Council is made up of seven representatives, each elected from single-member districts. They annually elect the president of the council on a rotating basis. In 2015, the President of the Tupelo City Council is Buddy Palmer. Other council members are Markel Whittington, Lynn Bryan, Willie Jennings, Mike Bryan and Nettie Davis.[23]

Jim Newell was elected to the City Council in 2013, but resigned August 1, 2014, when he moved out of the ward he represented. A special election was held to fill the vacancy is set for September 4, 2014.[24][25]

In 2013 Nettie Davis was elected by the council as President, becoming the first woman and first African American to hold the position. Davis has served on the council for four terms.[26]

Mayor Jack Reed did not seek reelection in 2013. Attorney Jason Shelton, a Democrat, was elected mayor on June 4, 2013, over council chairman Fred Pitts, a Republican.[27]

The city government has been honored with many awards in 2015, including: ° All-America City, National League of Cities (5th designation) [28] ° Mississippi Municipal League Award of Excellence[29] ° Southern Public Relations Federation Certificate of Merit, Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Southern Public Relations Federation Award of Excellence, Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Southern Public Relations Lantern Award (2), Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Mississippi Governor's Conference on Tourism Volunteer of the Year, Bev Crossen nominated by Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Mississippi Governor's Conference on Tourism Large Festival/Event Award, Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Mississippi Governor's Conference on Tourism Travel Media Award, Tupelo Convention and Visitors Bureau [30] ° Mississippi Urban Forest Council Lifetime Achievement David Knight [31] ° Mississippi Urban Forest Council 2015 Scenic Community Award [32] ° Mississippi Recreation and Parks Association Design Award, Joyner Splash Pad [33] ° Mississippi Recreation and Parks Association Award of Excellence in Special Events Sports Programing, Southern Zone Age Group Swimming Championship, The Tupelo Aquatic Center [33]

Education

Tupelo schools are served by the Tupelo Public School District. It participates in the MacBook Distribution Policy, which means students in grades 6-12 are each given a school-owned Apple MacBook to use during the school year. In 2008, Sports Illustrated ranked the high school athletic department as the third-best high school athletic program in the nation.[34]

For post-secondary education, the city has satellite campuses of the University of Mississippi, Itawamba Community College, and the Mississippi University for Women.

Media

The local daily newspaper is the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal.

Tupelo is home to three television stations serving the 133rd-ranked designated market area among 210 markets nationwide as determined by Nielsen Media Research: WTVA (9), an NBC and ABC affiliate; and WLOV (27), a Fox affiliate. Both stations are located just outside the Tupelo city limits on Beech Spring Road and were controlled by Frank K. Spain until his death on April 25, 2006.

The American Family Association, located in Tupelo, includes the national American Family Radio network and the OneNewsNow news service.

Notable people

- Elvis Presley (1935–1977), singer and actor

- Diplo (1978–present), DJ and rapper

- Real life brothers, Aaquil "Slim Jimmy" Brown (Born 1993) and Khalif "Swae Lee" Brown (Born 1995), from the successful rap duo Rae Sremmurd

- Todd Jordan (1970–present), American football player

- Brian Dozier (1987-present), American baseball player

- Chris Stratton (1990-present), American baseball player

- Alex Carrington (1987-present), American football player

- Dave Clark (baseball) (1962-present), American baseball player and coach

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-11-08.

- 1 2 3 "City of Tupelo - Attractions", 2006, City of Tupelo website

- ↑ Dale Cox (1935-01-08). "Tupelo, Mississippi - Historic Sites and Points of Interest". Exploresouthernhistory.com. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ "Tupelo, MS". GumTree Chronicles. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ "George "Machine Gun" Kelly: American Robber and Kidnapper". crimelibrary. 2007-07-18. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ↑ Capeloutoaccess, Susanna (December 29, 2013). "Phoenix police fatally shoot man suspected in multi-state robberies, cop killing". CNN.

- ↑ "Tupelo-Gainesville Outbreak", Digital Library of Georgia, 2008, retrieved 12 Sept 2011

- 1 2 "Significant Tornadoes Update 1992–1995", Mid-South Tornadoes, Mississippi State University

- ↑ "This Day In History; Tornadoes Devastate Tupelo and Gainesville", The History Channel online, retrieved 13 September 2011

- ↑ "The 10 deadliest U.S. tornadoes on record". CNN.com. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ Martis D. Ramage, Jr. Tupelo, Mississippi, Tornado of 1936,

- ↑ "Average Weather for Tupelo, MS - Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- ↑ "Climate Information for Tupelo - Mississippi - South - United States - Climate Zone". Climate-zone.com. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Community Facts: Tupelo city". Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ↑ "About Tupelo | City of Tupelo". Tupeloms.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ Dennis Seid, The Northeast Mississippi Business Journal, February 2006

- 1 2 "About the City of Tupelo" (2006), City of Tupelo website, web: TupeloMS-About: for Elvis, the Natchez Trace Parkway, and Tupelo Automobile Museum.

- ↑ "Pharr Mounds-National Register of Historic Places Indian Mounds of Mississippi Travel Itinerary". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- ↑ Tom Wicker. "Lyric History". Tctwebstage.com. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ Tupelo City Council

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ , Lee County Courier, 13 February 2014

- ↑ "Jason Shelton wins big: Tupelo elects 37-year-old mayor", NE Mississippi Daily Journal

- ↑ Rod Guajardo (2015-06-15). "Tupelo: All-America City again - Daily Journal". Djournal.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ↑ Rod Guajardo (2015-06-25). "Tupelo receives top municipal honor - Daily Journal". Djournal.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zack Orsborn (2015-10-01). "Tupelo CVB earns several awards - Daily Journal". Djournal.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ↑ "City of Tupelo - Mayor's Office - Timeline". Facebook. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ↑ Daily Journal (2015-08-23). "OUR OPINION: Stay steady on plan for reforesting Tupelo - Daily Journal". Djournal.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- 1 2 William Moore (2015-09-29). "Tupelo Parks & Recreation brings home awards - Daily Journal". Djournal.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ↑ "Top 25 athletic programs for 2007-08". Sportsillustrated.cnn.com. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tupelo, Mississippi. |

.jpg)

.svg.png)