United States presidential election, 1888

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

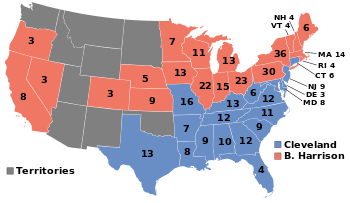

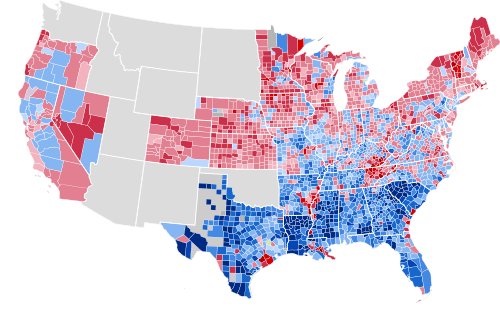

| Presidential election results map. Red denotes those won by Harrison/Morton, blue denotes states won by Cleveland/Thurman. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1888 was the 26th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 6, 1888. It saw Grover Cleveland of New York, the incumbent president and a Democrat, try to secure a second term against the Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana. The economy was prosperous and the nation was at peace, but Cleveland lost re-election in the Electoral College, even though he won a plurality of the popular vote by a narrow margin.

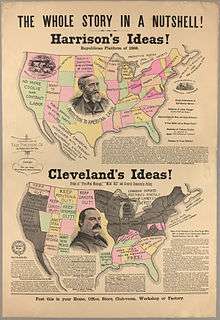

Tariff policy was the principal issue in the election. Harrison took the side of industrialists and factory workers who wanted to keep tariffs high, while Cleveland strenuously denounced high tariffs as unfair to consumers. His opposition to Civil War pensions and inflated currency also made enemies among veterans and farmers. On the other hand, he held a strong hand in the South and border states, and appealed to former Republican Mugwumps.

Harrison swept almost the entire North and Midwest (losing only Connecticut and New Jersey), and narrowly carried the swing states of New York (Cleveland's home state) and Indiana (Harrison's home state) by a margin of 1% or less to achieve a majority of the electoral vote. Unlike the election of 1884, the power of the Tammany Hall political machine in New York City helped deny Cleveland the electoral votes of his home state.

This election is notable for being the third of five U.S. presidential elections in which the winner did not get a plurality of the national popular vote. The first, in 1824, saw John Quincy Adams elected by the House of Representatives, defeating Andrew Jackson, who had won a plurality in both the electoral college and the popular vote. The second occurred in 1876 (Samuel J. Tilden versus Rutherford B. Hayes), the fourth in 2000 (Al Gore versus George W. Bush) and the fifth in 2016 (Hillary Clinton versus Donald Trump).[2] It is also notable because only two states (New York and Indiana) switched parties in the electoral vote from the preceding election. It would not be until the 2012 election that only two states (in that case, Indiana and North Carolina) would switch parties in consecutive elections.

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

The Democratic National Convention held in St. Louis, Missouri, on June 5–7, 1888, was harmonious. Incumbent President Cleveland was re-nominated unanimously without a formal ballot. This was the first time an incumbent Democratic president had been re-nominated since Martin Van Buren in 1840.

After Cleveland was re-nominated, Democrats had to choose a replacement for Thomas A. Hendricks. Hendricks ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic nominee for vice-president in 1876, but won the office when he ran again with Cleveland in 1884. Hendricks served as vice-president for only eight months before he died in office on November 25, 1885. Former Senator Allen G. Thurman from Ohio was nominated for vice-president over Isaac P. Gray, his nearest rival, and John C. Black, who trailed behind. Gray lost the nomination to Thurman primarily because his enemies brought up his actions while a Republican.[3]

The Democratic platform largely confined itself to a defense of the Cleveland administration, supporting reduction in the tariff and taxes generally as well as statehood for the western territories.

| Presidential Ballot | ||

| Unanimous | ||

|---|---|---|

| Grover Cleveland | 822 | |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

| 1st | Acclamation | |

|---|---|---|

| Allen G. Thurman | 684 | 822 |

| Isaac P. Gray | 101 | |

| John C. Black | 36 | |

| Blank | 1 | |

Republican Party nomination

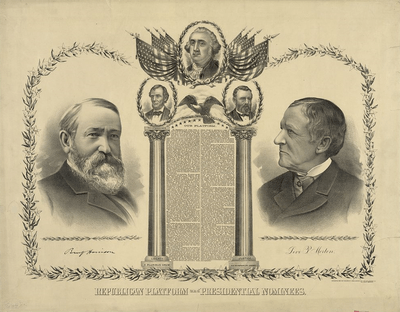

The Republican candidates were former Senator Benjamin Harrison from Indiana; Senator John Sherman from Ohio; Russell A. Alger, the former governor of Michigan; Walter Q. Gresham from Indiana, the former Secretary of the Treasury; Senator William B. Allison from Iowa; and Chauncey Depew from New York, the president of the New York Central Railroad.

By the time Republicans met in Chicago on June 19–25, 1888, frontrunner James G. Blaine had withdrawn from the race because he believed that only a harmonious convention would produce a Republican candidate strong enough to upset incumbent President Cleveland. Blaine realized that the party was unlikely to choose him without a bitter struggle. After he withdrew, Blaine expressed confidence in both Benjamin Harrison and John Sherman. Harrison was nominated on the eighth ballot.

The Republicans chose Harrison because of his war record, his popularity with veterans, his ability to express the Republican Party's views, and the fact that he lived in the swing state of Indiana. The Republicans hoped to win Indiana's 15 electoral votes, which had gone to Cleveland in the previous presidential election. Levi P. Morton, a New York City banker, was nominated for vice-president over William Walter Phelps, his nearest rival.

Prohibition Party nomination

Prohibition candidates:

- Clinton B. Fisk, U.S. Brigadier General from New Jersey

Candidates gallery

The 5th Prohibition Party National Convention assembled in Tomlinson Hall in Indianapolis, Indiana. There were 1,029 delegates from all but three states.

Clinton B. Fisk was nominated for president unanimously. John A. Brooks was nominated for vice-president.

The Prohibition ticket of Clinton B. Fisk and John Brooks went on to capture a quarter-million popular votes as the prohibition movement gained steam.[4]

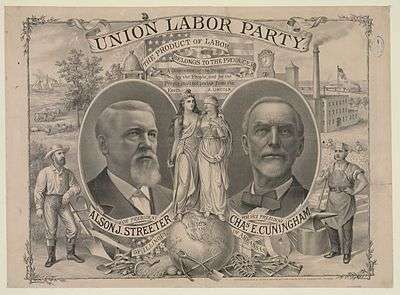

Union Labor Party nomination

Union Labor candidates:

- Alson Streeter from Illinois

-

Alson Streeter from Illinois

The Union Labor Party National Convention assembled in Cincinnati, Ohio. The Union Labor Party had been formed in 1887 in Cincinnati.

The United Labor Party held its national convention in Cincinnati at the same time. An attempt to nominate a joint ticket failed.

The convention nominated Alson Streeter for president unanimously. Samuel Evans was nominated for Vice President but declined the nomination. Charles E. Cunningham was later selected as the vice-presidential candidate.

The Union Labor Party garnered nearly 150,000 popular votes, but failed to gain widespread national support. The party did, however, win two counties.

| Presidential Ballot | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| Alson Streeter | 220 |

Source: US President – UL Convention. Our Campaigns. (February 11, 2012).

United Labor Party nomination

The United Labor Party National Convention assembled in the Grand Opera House in Cincinnati, Ohio. About 90 delegates attended. The party was founded to foster Henry George's single tax movement.

The convention was held at the same time and city as the Union Labor Party. An effort to run a joint ticket failed.

The United Labor Party convention nominated Robert H. Cowdrey for president on the first ballot. W.H.T. Wakefield of Kansas was nominated for vice-president over Victor H. Wilder from New York by a margin of 50–12.[5]

Greenback Party

The Greenback Party was in decline throughout the entire Cleveland administration. In the election of 1884, the party failed to win any House seats outright, although they did win one seat in conjunction with Plains States Democrats (James B. Weaver) and a handful of other seats by endorsing the Democratic nominee. In the election of 1886, only two dozen Greenback candidates ran for the House, apart from another six who ran on fusion tickets. Again, Weaver was the party's only victor. Much of the Greenback news in early 1888 took place in Michigan, where the party remained active.

In early 1888, it was not clear if the Greenback Party would hold another national convention. The fourth Greenback Party National Convention assembled in Cincinnati on May 16, 1888. So few delegates attended that no actions were taken. On August 16, 1888, George O. Jones, chairman of the national committee, called a second session of the national convention. The second session of the national convention met in Cincinnati on September 12, 1888. Only seven delegates attended. Chairman Jones issued an address criticizing the two major parties, and the delegates made no nominations.

With the failure of the convention, the Greenback Party ceased to exist.[6]

American Party nomination

The American Party held its third and last National Convention in Grand Army Hall in Washington, DC. This was an Anti-Masonic party that ran under various party labels in the northern states.

When the convention assembled, there were 126 delegates; among them were 65 from New York and 15 from California. Delegates from the other states bolted the convention when it appeared that New York and California intended to vote together on all matters and control the convention. By the time the presidential balloting began, there were only 64 delegates present.

The convention nominated James L. Curtis from New York for president and James R. Greer from Tennessee for vice-president. Greer declined to run, so Peter D. Wigginton of California was chosen as his replacement.[7]

Equal Rights Party nomination

The second Equal Rights Party National Convention assembled in Des Moines, Iowa. At the convention, mail-in ballots were counted. The delegates cast 310 of their 350 ballots for the following ticket: Belva A. Lockwood for president and Alfred H. Love for vice-president.

Love was later replaced with Charles S. Wells NY.[8]

Industrial Reform Party nomination

The Industrial Reform Party National Convention assembled in Grand Army Hall, Washington, DC. There were 49 delegates present.

Albert Redstone won the endorsement of some leaders of the disintegrating Greenback Party. He told the Montgomery Advertiser that he would carry several states, including Alabama, New York, North Carolina, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri.[9]

General election campaign

Issues

Cleveland set the main issue of the campaign when he proposed a dramatic reduction in tariffs in his annual message to Congress in December 1887. Cleveland contended that the tariff was unnecessarily high and that unnecessary taxation was unjust taxation. The Republicans responded that the high tariff would protect American industry from foreign competition and guarantee high wages, high profits, and high economic growth.

The argument between protectionists and free traders over the size of the tariff was an old one, stretching back to the Tariff of 1816. In practice, the tariff was practically meaningless on industrial products, since the United States was the low-cost producer in most areas (except woolens), and could not be undersold by the less efficient Europeans. Nevertheless, the tariff issue motivated both sides to a remarkable extent.

Besides the obvious economic dimensions, the tariff argument also possessed an ethnic dimension. At the time, the policy of free trade was most strongly promoted by the British Empire, and so any political candidate who ran on free trade instantly was under threat of being labelled pro-British and antagonistic to the Irish-American voting bloc. Cleveland neatly neutralized this threat by pursuing punitive action against Canada (which, although autonomous, was still part of the British Empire) in a fishing rights dispute.

Harrison was well-funded by party activists and mounted an energetic campaign by the standards of the day, giving many speeches from his front porch in Indianapolis that were covered by the newspapers. Cleveland adhered to the tradition of presidential candidates not campaigning, and forbade his cabinet from campaigning as well, leaving his 75-year-old vice-presidential candidate Thurman as the spearhead of his campaign.

Blocks of Five

William Wade Dudley (1842–1909), an Indianapolis lawyer, was a tireless campaigner and prosecutor of Democratic election frauds. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison made Dudley Treasurer of the Republican National Committee. The campaign was the most intense in decades, with Indiana dead even. Although the National Committee had no business meddling in state politics, Dudley wrote a circular letter to Indiana's county chairmen, telling them to "divide the floaters into Blocks of Five, and put a trusted man with the necessary funds in charge of these five, and make them responsible that none get away and that all vote our ticket." Dudley promised adequate funding. His pre-emptive strike backfired when Democrats obtained the letter and distributed hundreds of thousands of copies nationwide in the last days of the campaign. Given Dudley's unsavory reputation, few people believed his denials. A few thousand "floaters" did exist in Indiana—men who would sell their vote for $2. They always divided 50-50 (or perhaps, $5,000-$5,000) and had no visible impact on the vote. The attack on "blocks of five" with the suggestion that pious General Harrison was trying to buy the election did enliven the Democratic campaign, and it stimulated the nationwide movement to replace ballots printed and distributed by the parties with secret ballots.[10]

Murchison letter

A California Republican named George Osgoodby wrote a letter to Sir Lionel Sackville-West, the British ambassador to the United States, under the assumed name of "Charles F. Murchison," describing himself as a former Englishman who was now a California citizen and asked how he should vote in the upcoming presidential election. Sir Lionel wrote back and in the "Murchison letter" indiscreetly suggested that Cleveland was probably the best man from the British point of view.

The Republicans published this letter just two weeks before the election, where it had an effect on Irish-American voters exactly comparable to the "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion" blunder of the previous election: Cleveland lost New York and Indiana (and as a result, the presidency). Sackville-West was removed as British ambassador.[11]

Election results

The election focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Harrison's home state of Indiana.[12] Harrison and Cleveland split these four states, with Harrison winning by means of notoriously fraudulent balloting in New York and Indiana.[13]

1888 marked the third election in U.S. history in which the winning candidate received fewer popular votes than the runner-up. Grover Cleveland defeated Benjamin Harrison in the popular vote by slightly more than 90,000 votes (0.8%). Harrison, however, won the Electoral College (United States) by a 233-168 margin, largely by virtue of his 1.09% percent win in Cleveland's home state of New York.

Had Cleveland won his home state, he would have won the electoral vote by an electoral count of 204-197 (201 electoral votes were needed for victory in 1888). Instead, Cleveland became the third of only five candidates to win the popular vote but lose their respective presidential elections (Andrew Jackson in 1824, Samuel J. Tilden in 1876, Al Gore in 2000, and Hillary Clinton in 2016).

Four states returned results where the winner won by less than 1 percent of the popular vote. Cleveland earned 24 of his electoral votes from states he won by less than 1 percent: Connecticut, Virginia, and West Virginia. Harrison earned 15 of his electoral votes from a state he won by less than 1 percent: Indiana. Harrison won New York (36 electoral votes) by a margin of 1.09%. Despite the narrow margins in several states, only two states switched sides in comparison to Cleveland's first presidential election (New York and Indiana).

Of the 2,450 counties/independent cities making returns, Cleveland won in 1,290 (52.65%) while Harrison carried 1,157 (47.22%). Two counties (0.08%) recorded a Streeter plurality while one county (0.04%) in California split evenly between Cleveland and Harrison.

Upon leaving the White House at the end of her husband's first term, First Lady Frances Cleveland is reported to have told the White House staff to take care of the building since the Clevelands would be returning in four years. She proved correct, becoming the only First Lady to preside at two nonconsecutive administrations.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Pct | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Elect. vote | ||||

| Benjamin Harrison | Republican | Indiana | 5,443,892 | 47.80% | 233 | Levi P. Morton | New York | 233 |

| Grover Cleveland (Incumbent) | Democratic | New York | 5,534,488 | 48.63% | 168 | Allen G. Thurman | Ohio | 168 |

| Clinton B. Fisk | Prohibition | New Jersey | 249,819 | 2.20% | 0 | John A. Brooks | Missouri | 0 |

| Alson Streeter | Union Labor | Illinois | 146,602 | 1.31% | 0 | Charles E. Cunningham | Arkansas | 0 |

| Other | 8,519 | 0.07% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 11,383,320 | 100% | 401 | 401 | ||||

| Needed to win | 201 | 201 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1888 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Geography of Results

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic Gallery

-

Map of presidential election results by county.

-

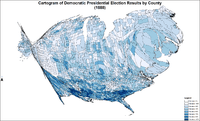

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county.

-

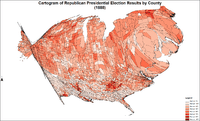

Map of Republican presidential election results by county.

-

Map of "other" presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county.

-

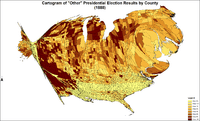

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county.

Results by state

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.[14]

| States won by Cleveland/Thurman |

| States won by Harrison/Morton |

| Grover Cleveland Democratic |

Benjamin Harrison Republican |

Clinton Fisk Prohibition |

Alson Streeter Union Labor |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 10 | 117,314 | 67.00 | 10 | 57,177 | 32.66 | - | 594 | 0.34 | - | - | - | - | 60,137 | 34.35 | 175,085 | AL |

| Arkansas | 7 | 86,062 | 54.80 | 7 | 59,752 | 38.04 | - | 614 | 0.39 | - | 10,630 | 6.77 | - | 26,310 | 16.75 | 157,058 | AR |

| California | 8 | 117,729 | 46.84 | - | 124,816 | 49.66 | 8 | 5,761 | 2.29 | - | - | - | - | -7,087 | -2.82 | 251,339 | CA |

| Colorado | 3 | 37,549 | 40.84 | - | 50,772 | 55.22 | 3 | 2,182 | 2.37 | - | 1,266 | 1.38 | - | -13,223 | -14.38 | 91,946 | CO |

| Connecticut | 6 | 74,920 | 48.66 | 6 | 74,584 | 48.44 | - | 4,234 | 2.75 | - | 240 | 0.16 | - | 336 | 0.22 | 153,978 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 16,414 | 55.15 | 3 | 12,950 | 43.51 | - | 399 | 1.34 | - | - | - | - | 3,464 | 11.64 | 29,764 | DE |

| Florida | 4 | 39,557 | 59.48 | 4 | 26,529 | 39.89 | - | 414 | 0.62 | - | - | - | - | 13,028 | 19.59 | 66,500 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 100,493 | 70.31 | 12 | 40,499 | 28.33 | - | 1,808 | 1.26 | - | 136 | 0.10 | - | 59,994 | 41.97 | 142,936 | GA |

| Illinois | 22 | 348,351 | 46.58 | - | 370,475 | 49.54 | 22 | 21,703 | 2.90 | - | 7,134 | 0.95 | - | -22,124 | -2.96 | 747,813 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 261,013 | 48.61 | - | 263,361 | 49.05 | 15 | 9,881 | 1.84 | - | 2,694 | 0.50 | - | -2,348 | -0.44 | 536,949 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 179,877 | 44.51 | - | 211,603 | 52.36 | 13 | 3,550 | 0.88 | - | 9,105 | 2.25 | - | -31,726 | -7.85 | 404,135 | IA |

| Kansas | 9 | 102,745 | 31.03 | - | 182,904 | 55.23 | 9 | 6,779 | 2.05 | - | 37,788 | 11.41 | - | -80,159 | -24.21 | 331,149 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 183,830 | 53.30 | 13 | 155,138 | 44.98 | - | 5,223 | 1.51 | - | 677 | 0.20 | - | 28,692 | 8.32 | 344,868 | KY |

| Louisiana | 8 | 85,032 | 73.37 | 8 | 30,660 | 26.46 | - | 160 | 0.14 | - | 39 | 0.03 | - | 54,372 | 46.92 | 115,891 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 50,472 | 39.35 | - | 73,730 | 57.49 | 6 | 2,691 | 2.10 | - | 1,344 | 1.05 | - | -23,258 | -18.13 | 128,253 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 106,188 | 50.34 | 8 | 99,986 | 47.40 | - | 4,767 | 2.26 | - | - | - | - | 6,202 | 2.94 | 210,941 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 151,590 | 44.04 | - | 183,892 | 53.42 | 14 | 8,701 | 2.53 | - | - | - | - | -32,302 | -9.38 | 344,243 | MA |

| Michigan | 13 | 213,469 | 44.91 | - | 236,387 | 49.73 | 13 | 20,945 | 4.41 | - | 4,555 | 0.96 | - | -22,918 | -4.82 | 475,356 | MI |

| Minnesota | 7 | 104,385 | 39.65 | - | 142,492 | 54.12 | 7 | 15,311 | 5.82 | - | 1,097 | 0.42 | - | -38,107 | -14.47 | 263,285 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 85,451 | 73.80 | 9 | 30,095 | 25.99 | - | 240 | 0.21 | - | - | - | - | 55,356 | 47.81 | 115,786 | MS |

| Missouri | 16 | 261,943 | 50.24 | 16 | 236,252 | 45.31 | - | 4,539 | 0.87 | - | 18,626 | 3.57 | - | 25,691 | 4.93 | 521,360 | MO |

| Nebraska | 5 | 80,552 | 39.75 | - | 108,425 | 53.51 | 5 | 9,429 | 4.65 | - | 4,226 | 2.09 | - | -27,873 | -13.76 | 202,632 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 5,149 | 41.94 | - | 7,088 | 57.73 | 3 | 41 | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | -1,939 | -15.79 | 12,278 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 43,456 | 47.84 | - | 45,728 | 50.34 | 4 | 1,593 | 1.75 | - | - | - | - | -2,272 | -2.50 | 90,835 | NH |

| New Jersey | 9 | 151,508 | 49.87 | 9 | 144,360 | 47.52 | - | 7,933 | 2.61 | - | - | - | - | 7,148 | 2.35 | 303,801 | NJ |

| New York | 36 | 635,965 | 48.19 | - | 650,338 | 49.28 | 36 | 30,231 | 2.29 | - | 627 | 0.05 | - | -14,373 | -1.09 | 1,319,748 | NY |

| North Carolina | 11 | 147,902 | 51.79 | 11 | 134,784 | 47.20 | - | 2,840 | 0.99 | - | - | - | - | 13,118 | 4.59 | 285,563 | NC |

| Ohio | 23 | 396,455 | 47.18 | - | 416,054 | 49.51 | 23 | 24,356 | 2.90 | - | 3,496 | 0.42 | - | -19,599 | -2.33 | 840,361 | OH |

| Oregon | 3 | 26,522 | 42.88 | - | 33,291 | 53.82 | 3 | 1,677 | 2.71 | - | - | - | - | -6,769 | -10.94 | 61,853 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 30 | 446,633 | 44.77 | - | 526,091 | 52.74 | 30 | 20,947 | 2.10 | - | 3,873 | 0.39 | - | -79,458 | -7.97 | 997,568 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 17,530 | 42.99 | - | 21,969 | 53.88 | 4 | 1,251 | 3.07 | - | 18 | 0.04 | - | -4,439 | -10.89 | 40,775 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 65,824 | 82.28 | 9 | 13,736 | 17.17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 52,088 | 65.11 | 79,997 | SC |

| Tennessee | 12 | 158,699 | 52.26 | 12 | 138,978 | 45.76 | - | 5,969 | 1.97 | - | 48 | 0.02 | - | 19,721 | 6.49 | 303,694 | TN |

| Texas | 13 | 234,883 | 65.70 | 13 | 88,422 | 24.73 | - | 4,749 | 1.33 | - | 29,459 | 8.24 | - | 146,461 | 40.97 | 357,513 | TX |

| Vermont | 4 | 16,788 | 25.65 | - | 45,192 | 69.05 | 4 | 1,460 | 2.23 | - | 1,977 | 3.02 | - | -28,404 | -43.40 | 65,452 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 152,004 | 49.99 | 12 | 150,399 | 49.46 | - | 1,684 | 0.55 | - | - | - | - | 1,605 | 0.53 | 304,087 | VA |

| West Virginia | 6 | 78,677 | 49.35 | 6 | 78,171 | 49.03 | - | 1,084 | 0.68 | - | 1,508 | 0.95 | - | 506 | 0.32 | 159,440 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 11 | 155,232 | 43.77 | - | 176,553 | 49.79 | 11 | 14,277 | 4.03 | - | 8,552 | 2.41 | - | -21,321 | -6.01 | 354,614 | WI |

| TOTALS: | 401 | 5,538,163 | 48.63 | 168 | 5,443,633 | 47.80 | 233 | 250,017 | 2.20 | - | 149,115 | 1.31 | - | 94,530 | 0.83 | 11,388,846 | US |

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (189 electoral votes):

- Connecticut, 0.22%

- West Virginia, 0.32%

- Indiana, 0.44%

- Virginia, 0.53%

- New York, 1.09%

- Ohio, 2.33%

- New Jersey, 2.35%

- New Hampshire, 2.50%

- California, 2.82%

- Maryland, 2.94%

- Illinois, 2.96%

- North Carolina, 4.59%

- Michigan, 4.82%

- Missouri, 4.93%

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (93 electoral votes):

- Wisconsin, 6.01%

- Tennessee, 6.49%

- Iowa, 7.85%

- Pennsylvania, 7.97%

- Kentucky, 8.32%

- Massachusetts, 9.38%

In popular culture

In 1968 the Michael P. Antoine Company produced the Walt Disney Company musical film The One and Only, Genuine, Original Family Band which centers around the election of 1888 and the annexing and subdividing of the Dakota Territory into states (which was a major issue of the election).

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- Inauguration of Benjamin Harrison

- Third Party System

Footnotes

- ↑ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- ↑ Gaines 2001.

- ↑ Jacob Piatt Dunn, George William Harrison Kemper, Indiana and Indianans (p. 724).

- ↑ United States Presidential Elections. PediaPress.

- ↑ "US President UtL Convention Race – May 15, 1888". Our Campaigns. 2006-01-28. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ "US President GNB Convention Race – May 16, 1888". Our Campaigns. 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ "US President Am Convention Race – Aug 14, 1888". Our Campaigns. 2006-01-28. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ "US President ER Convention Race – May 16, 1888". Our Campaigns. 2006-01-28. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ "US President IRf Convention Race – Feb 22, 1888". Our Campaigns. 2006-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ Jensen, Winning of the Midwest (1971) ch 1

- ↑ Charles W. Calhoun, Minority Victory: Gilded Age Politics and the Front Porch Campaign of 1888 (2008).

- ↑ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 10.

- ↑ Calhoun, p. 43; Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 13.

- ↑ "1888 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved May 7, 2013.

References

Secondary sources

- Baumgarden, James L. (Summer 1984). "The 1888 Presidential Election: How Corrupt?". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 14: 416–27.

- Calhoon, Robert M. "Gilded Age Statecraft," Reviews in American History Volume 38, Number 1, March 2010 in Project MUSE

- Calhoun, Charles W. (2008). Minority Victory: Gilded Age Politics and the Front Porch Campaign of 1888. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1596-4.

- Gaines, Brian J. (March 2001). "Popular Myths about Popular Vote-Electoral College Splits". PS: Political Science and Politics. 34: 70–75. doi:10.1017/s1049096501000105.

- Jensen, Richard (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39825-0. online free

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1969). From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2136-1.

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: a study in courage (1933), the standard biography

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. A History of the United States since the Civil War. Volume V, 1888–1901 (1937). pp 1-74.

- Reitano, Joanne R. (1994). The Tariff Question in the Gilded Age: The Great Debate of 1888. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01035-5.

- Shenkman, Rick (2004). "Who Played the First Dirty Tricks in American Presidential Politics?". History News Network. Retrieved April 4, 2005.

- Sievers, Harry. Benjamin Harrison: from the Civil War to the White House, 1865–1888 (1959), standard biography

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren (2004). Party Games: Getting, Keeping, and Using Power in Gilded Age Politics. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2862-9. excerpt and text search

Primary sources

- Dawson, George Francis (1888). The Republican Campaign Text-book for 1888. New York: Brentano's.

- The campaign text book of the Democratic party of the United States, for ...1888 (1888) full text online, the compilation of data, texts and political arguments used by stump speakers across the country

- Cleveland, Grover. Letters and Addresses of Grover Cleveland (1909) online edition

- Cleveland, Grover. The Letters of Grover Cleveland (1937), edited by Allan Nevins.

- Harrison, Benjamin. Speeches of Benjamin Harrison, twenty-third President of the United States (1890), contains his 1888 campaign speeches full text online

External links

- Presidential Election of 1888: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1888 popular vote by counties

- How close was the 1888 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Election of 1888 in Counting the Votes

- The Vote That Failed. Smithsonian Magazine article on Indiana in the 1888 election.