Whig Party (United States)

Whig Party | |

|---|---|

| Historical leaders |

Henry Clay Daniel Webster |

| Founded | 1833 |

| Dissolved | 1854 |

| Merger of |

National Republican Party Anti-Masonic Party |

| Succeeded by |

Know Nothing Party Republican Party Opposition Party (Opposition to Slavery) Opposition Party (Opposition to Secession) |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Newspaper | The American Review: A Whig Journal |

| Ideology |

American System (economic plan) Protectionism Non-interventionism |

| International affiliation | None |

| Colors | Blue and buff |

The Whig Party was a political party active in the middle of the 19th century in the United States. Four Presidents belonged to the Party while in office.[1] It emerged in the 1830s as the immediate successor to the National Republican and Anti-Masonic Parties, and was also rooted in the traditional of the Federalist Party. Along with the rival Democratic Party, it was central to the Second Party System from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s.[2] It originally formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson (in office 1829–37) and his Democratic Party. In particular, the Whigs supported the supremacy of Congress over the Presidency and favored a program of modernization, banking and economic protectionism to stimulate manufacturing. It appealed to entrepreneurs, planters, reformers and the emerging urban middle class, but had little appeal to farmers or unskilled workers. It included many active Protestants, and voiced a moralistic opposition to the Jacksonian Indian removal policies. Party founders chose the "Whig" name to echo the American Whigs of 1776, who fought for independence. "Whig" meant opposing tyranny. The underlying political philosophy of the American Whig Party was not directly related to the Whig party in England.[3] Historian Frank Towers has specified a deep ideological divide:

Democrats stood for the 'sovereignty of the people' as expressed in popular demonstrations, constitutional conventions, and majority rule as a general principle of governing, whereas Whigs advocated the rule of law, written and unchanging constitutions, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny.[4]

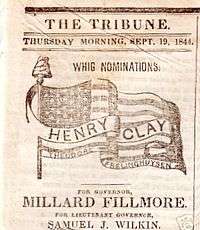

The Whig Party nominated several presidential candidates in 1836. General William Henry Harrison of Ohio was nominated in the 1840, Congressman Henry Clay of Kentucky in 1844, and General Zachary Taylor of Virginia in 1848. Another war-hero, General Winfield Scott of Virginia was the Whig Party's last presidential nominee in the 1852. In its two decades of existence, the Whig Party had two of its candidates, Harrison and Taylor, elected President. Both died in office. John Tyler succeeded to the Presidency after Harrison's death in 1841, but was expelled from the party. Millard Fillmore, who became President after Taylor's death in 1850, was the last Whig president.

The party fell apart because of the internal tension over the expansion of slavery to the territories. With deep fissures in the party on this question, the anti-slavery faction prevented the nomination for a full-term of its own incumbent, President Fillmore, in the 1852 presidential election; instead, the party nominated General Scott. Most Whig Party leaders eventually quit politics (as Abraham Lincoln did temporarily) or changed parties. The northern voter-base mostly gravitated to the new Republican Party. In the South, most joined the Know Nothing Party, which unsuccessfully ran Fillmore in the 1856 presidential election, by which time the Whig Party had become virtually defunct. Some former Whigs became Democrats. The Constitutional Union Party experienced significant success from conservative former Whigs in the Upper South during the 1860 presidential election. Whig ideology as a policy orientation persisted for decades and played a major role in shaping the modernizing policies of the state governments during Reconstruction.[5]

History

Origins

The name Whig derived from a term that Patriots used to refer to themselves during the American Revolution. It indicated hostility to the British Sovereign, and despite the identical name, did not directly derive from the British Whig Party (see etymology).[6]

The American Whigs were modernizers who saw President Andrew Jackson as "a dangerous man on horseback" with a "reactionary opposition" to the forces of social, economic, and moral modernization. The Democratic-Republicans who formed the Whig Party, led by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, drew on a Jeffersonian tradition of compromise, balance in government, and territorial expansion combined with national unity and support for a Federal transportation network and domestic manufacturing. Casting their enemy as "King Andrew", they sought to identify themselves as modern-day opponents of governmental overreaching.

Despite the apparent unity of Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans from 1800 to 1824, the American people ultimately preferred partisan opposition to popular political agreement.[7] As Jackson purged his opponents, vetoed internal improvements, and killed the Second Bank of the United States, alarmed local elites fought back. In 1831, Henry Clay re-entered the Senate and started planning a new party. He defended national rather than sectional interests. Clay's plan for distributing the proceeds from the sale of lands among the states in the public domain was intended to serve the nation by providing the states with funds for building roads and canals, which would stimulate growth and knit the sections together. His Jacksonian opponents, however, distrusted the federal government and opposed all federal aid for internal improvements and they again frustrated Clay's plan. Jacksonians promoted opposition to the National Bank and internal improvements and support of egalitarian democracy, state power, and hard money.

The "Tariff of Abominations" of 1828 had outraged Southern feelings; the South's leaders held that the high duties on foreign imports gave an advantage to the North (where the factories were located). Clay's own high tariff schedule of 1832 further disturbed them, as did his stubborn defense of high duties as necessary to his "American System". Clay however moved to pass the Compromise of 1833, which met Southern complaints by a gradual reduction of the rates on imports to a maximum of twenty percent. Controlling the Senate for a while, Whigs passed a censure motion denouncing Jackson's arrogant assumption of executive power in the face of the true will of the people as represented by Congress.

The Whig Party began to take shape in 1833. Clay had run as a National Republican against Jackson in 1832, but carried only 49 electoral votes against Jackson's 219, and the National Republicans became discredited as a major political force. The Whig Party emerged in the aftermath of the 1832 election, the Nullification Crisis, and debates regarding the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson denounced as a monopoly and from which he abruptly removed all government deposits. People who helped to form the new party included supporters of Clay, supporters of Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, former National Republicans, former Antimasons, former disaffected Jacksonians (led by John C. Calhoun), who viewed Jackson's actions as impinging on the prerogatives of Congress and the states, and small remnants of Federalist Party, people whose last political activity was with them a decade before. The "Whig" name emphasized the party's opposition to Jackson's perceived executive tyranny, and the name helped the Whigs shed the elitist image of the National Republican Party.[8]

Clay was the clear leader of the Whig Party nationwide and in Washington, but he was vulnerable to Jacksonian allegations that he associated with the upper class at a time when white males without property had the right to vote and wanted someone more like themselves. The Whigs nominated a war hero in 1840—and emphasized that William Henry Harrison had given up the high life to live in a log cabin on the frontier. Harrison won.

Rise

In the 1836 elections, the party was not yet sufficiently organized or unified to run one nationwide candidate; instead William Henry Harrison was its candidate in the northern and border states, Hugh Lawson White ran in the South, Daniel Webster ran in his home state of Massachusetts, and in South Carolina, the Whig's presidential candidate was Willie P. Mangum. Whigs hoped that four candidates would amass enough Electoral College votes among them to deny a majority to Martin Van Buren. That would move the election to the House of Representatives, allowing the ascendant Whigs to select their most popular man as president.

Van Buren won 170 ballots in the Electoral College, with only 148 ballots needed to win. But the Whig strategy came very close to succeeding. In Pennsylvania, which had 30 ballots in the Electoral College, Harrison got 87,235 votes to Van Buren's 91,457. A change of just a few thousand votes in that state would have reduced Van Buren's ballot count to only 140, eight short of winning.

In late 1839, the Whigs held their first national convention and nominated William Henry Harrison as their presidential candidate. In March 1840, Harrison pledged to serve only one term as President if elected, a pledge that reflected popular support for a Constitutional limit to Presidential terms among many in the Whig Party. Harrison went on to victory in 1840, defeating Van Buren's re-election bid largely as a result of the Panic of 1837 and subsequent depression. Harrison served only 31 days and became the first President to die in office. He was succeeded by John Tyler, a Virginian and states' rights absolutist. Tyler vetoed the Whig economic legislation and was expelled from the Whig party in September 1841.

The Whigs' internal disunity and the nation's increasing prosperity made the party's activist economic program seem less necessary and led to a disastrous showing in the 1842 Congressional election.

A brief golden age

The central issue in the 1840s was expansion, with proponents of "Manifest Destiny" arguing for aggressive westward expansion, even at the risk of war with Mexico (over the annexation of Texas) and Britain (over control of Oregon). Howe argues that, "Nevertheless American imperialism did not represent an American consensus; it provoked bitter dissent within the national polity."[9] That is, most Democrats strongly supported Manifest Destiny and most Whigs strongly opposed it.

Faragher's analysis of the political polarization between the parties is that:

- "Most Democrats were wholehearted supporters of expansion, whereas many Whigs (especially in the North) were opposed. Whigs welcomed most of the changes wrought by industrialization but advocated strong government policies that would guide growth and development within the country's existing boundaries; they feared (correctly) that expansion raised a contentious issue the extension of slavery to the territories. On the other hand, many Democrats feared industrialization the Whigs welcomed. ... For many Democrats, the answer to the nation's social ills was to continue to follow Thomas Jefferson's vision of establishing agriculture in the new territories in order to counterbalance industrialization."[10]

By 1844, the Whigs began their recovery by nominating Henry Clay, who lost the presidential race to Democrat James K. Polk in a closely contested race, with Polk's policy of western expansion (particularly the annexation of Texas) and free trade triumphing over Clay's protectionism and caution over the Texas question. The Whigs, both northern and southern, strongly opposed expansion into Texas, which they (including Whig Congressman Abraham Lincoln) saw as an unprincipled land grab.

In 1848, the Whigs, seeing no hope of success by nominating Clay, nominated General Zachary Taylor, a hero of the Mexican–American War. They stopped criticizing the war and adopted only a very vague platform. Taylor defeated Democratic candidate Lewis Cass and the anti-slavery Free Soil Party, who had nominated former President Martin Van Buren. Van Buren's candidacy split the Democratic vote in New York, throwing that state to the Whigs; at the same time, however, the Free Soilers probably cost the Whigs several Midwestern states.

Compromise of 1850

Taylor was firmly opposed to the proposed Compromise of 1850, an initiative of Clay, and was committed to the admission of California as a free state. He proclaimed that he would take military action to prevent the secession of southern states. On July 9, 1850, Taylor died; Vice President Millard Fillmore, a long-time Whig, became President. Fillmore helped push the Compromise through Congress in the hopes of ending the controversies over slavery; its five separate bills became law in September 1850.

After 1850, the Whigs were unable to deal with the slavery issue. Their southern leaders nearly all owned slaves. The northeastern Whigs, led by Daniel Webster, represented businessmen who loved national unity and a national market but cared little about slavery one way or another. However, many Whig voters in the North thought that slavery was incompatible with a free-labor, free-market economy, and supported the Wilmot Proviso, which did not pass Congress but would have stopped the expansion of slavery. No one found a compromise that would keep the party united. Furthermore, the burgeoning economy made full-time careers in business or law much more attractive than politics for ambitious young Whigs. Thus the Whig Party leader in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, simply abandoned politics after 1849, instead attending to his law business.

Decline

When new issues of nativism, prohibition, and anti-slavery burst on the scene in the mid-1850s, few looked to the quickly disintegrating Whig Party for answers. In the North most ex-Whigs joined the new Republican Party, and in the South, they flocked to a new short-lived American Party.

The election of 1852 marked the beginning of the end for the Whigs. The deaths of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster that year severely weakened the party. The Compromise of 1850 had fractured the Whigs along pro- and anti-slavery lines, with the anti-slavery faction having enough power to deny Fillmore the party's nomination in 1852. The Whig Party's 1852 convention in New York City saw the historic meeting between Alvan E. Bovay and The New York Tribune's Horace Greeley, a meeting that led to correspondence between the men as the early Republican Party meetings in 1854 began to take place.

Attempting to repeat their earlier successes, the Whigs nominated popular General Winfield Scott, who lost decisively to the Democrats' Franklin Pierce. The Democrats won the election by a large margin: Pierce won 27 of the 31 states, including Scott's home state of New Jersey. Whig Representative Lewis D. Campbell of Ohio was particularly distraught by the defeat, exclaiming, "We are slain. The party is dead—dead—dead!" Increasingly, politicians realized that the party was a loser.

In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which opened the new territories to slavery, was passed. Southern Whigs generally supported the Act while Northern Whigs remained strongly opposed. Most remaining Northern Whigs, like Lincoln, joined the new Republican Party and strongly attacked the Act, appealing to widespread northern outrage over the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Other Whigs joined the Know-Nothing Party, attracted by its nativist crusades against so-called "corrupt" Irish and German immigrants. In the South, the Whig party vanished, but as Thomas Alexander has shown, Whiggism as a modernizing policy orientation persisted for decades.[5] Historians estimate that, in the South in 1856, former Whig Fillmore retained 86 percent of the 1852 Whig voters when he ran as the American Party candidate. He won only 13% of the northern vote, though that was just enough to tip Pennsylvania out of the Republican column. The future in the North, most observers thought at the time, was Republican. Scant prospects for the shrunken old party seemed extant, and after 1856 virtually no Whig organization remained at the regional level.[11] Twenty-six states sent 150 delegates to the last national convention in September 1856. The convention met for only two days and on the second day (and only ballot) quickly nominated Fillmore for president, who had already been nominated for president by the Know Nothing party. Andrew Jackson Donelson was nominated for vice president. Some Whigs and others adopted the mantle of the Opposition Party for several years and enjoyed some individual electoral successes.

Legacy

In 1860, many former Whigs who had not joined the Republicans regrouped as the Constitutional Union Party, which nominated only a national ticket. It had considerable strength in the border states, which feared the onset of civil war. Its presidential candidate, John Bell, finished third in the electoral college.

During the Lincoln Administration (1861–65), ex-Whigs dominated the Republican Party and enacted much of their American System. Later their Southern colleagues dominated the White response to Reconstruction. In the long run, America adopted Whiggish economic policies coupled with a Democratic strong presidency.

During the latter part of the American Civil War, and during the Reconstruction Era, many former Whigs tried to regroup in the South, calling themselves "Conservatives" and hoping to reconnect with the ex-Whigs in the North. These were merged into the Democratic Party in the South, but they continued to promote modernization policies such as large-scale railroad construction and the founding of public schools.[5]

In today's discourse in American politics, the Whig Party is often cited as an example of a political party that lost its followers and its reason for being, as by the expression "going the way of the Whigs,"[12] a term referred to by Donald Critchlow in his book, The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History.[13] Critchlow points out that the application of the term by Republicans in the GOP of 1974 may have been a misnomer; the old Whig party enjoyed more political support before its demise than the GOP in the aftermath of Nixon's resignation.

Party platform

The Whigs suffered greatly from factionalism throughout their existence, as well as weak party loyalty that stood in contrast to the strong party discipline that was the hallmark of a tight Democratic Party organization.[14] One strength of the Whigs, however, was a superb network of newspapers; their leading editor was Horace Greeley of the powerful New York Tribune.

In the 1840s Whigs won 49 percent of gubernatorial elections, with strong bases in the manufacturing Northeast and in the border states. The trend over time, however, was for the Democratic vote to grow faster and for the Whigs to lose more and more marginal states and districts. After the close 1844 contest, the Democratic advantage widened and the Whigs could win the White House only if the Democrats split. This was partly because of the increased political importance of the western states, which generally voted for Democrats, and Irish Catholic and German immigrants, who voted heavily for the Democrats.

The Whigs appealed to voters in every socio-economic category but proved especially attractive to the professional and business classes: doctors, lawyers, merchants, ministers, bankers, storekeepers, factory owners, commercially oriented farmers and large-scale planters. In general, commercial and manufacturing towns and cities voted Whig, save for strongly Democratic precincts in Irish Catholic and German immigrant communities; the Democrats often sharpened their appeal to the poor by ridiculing the Whigs' aristocratic pretensions. Protestant religious revivals also injected a moralistic element into the Whig ranks.[15]

Whig issues

The Whigs celebrated Clay's vision of the "American System" that promoted rapid economic and industrial growth in the United States. Whigs demanded government support for a more modern, market-oriented economy, in which skill, expertise and bank credit would count for more than physical strength or land ownership. Whigs sought to promote faster industrialization through high tariffs, a business-oriented money supply based on a national bank and a vigorous program of government funded "internal improvements" (what we now call infrastructure projects), especially expansion of the road and canal systems. To modernize the inner America, the Whigs helped create public schools, private colleges, charities, and cultural institutions. Many were pietistic Protestant reformers who called for public schools to teach moral values and proposed prohibition to end the liquor problem.

The Democrats harkened to the Jeffersonian ideal of an egalitarian agricultural society, advising that traditional farm life bred republican simplicity, while modernization threatened to create a politically powerful caste of rich aristocrats who threatened to subvert democracy. In general the Democrats enacted their policies at the national level, while the Whigs succeeded in passing modernization projects in most states.

Education

Arguing that universal public education was the best way to turn the nation's unruly children into disciplined, judicious republican citizens, Horace Mann (1796–1859) won widespread approval from modernizers, especially among fellow Whigs, for building public schools. Indeed, most states adopted one version or another of the system he established in Massachusetts, especially the program for normal schools to train professional teachers.[16]

Namesakes

In Liberia, the True Whig Party—named in direct emulation of the American Whig party, was founded in 1869. It dominated politics in that country from 1878 until 1980.[17]

Occasionally small groups in the U.S. form parties that take the Whig name. They seldom last long or elect anyone. In 2006, the Florida Whig Party was formed and fielded one candidate for Congress in the elections of 2010. It disbanded in 2012.[18]

In 2008, a group of veterans formed the Modern Whig Party.[19] It occasionally claimed a local officeholder supported this party.

The Quincy Herald-Whig, a daily newspaper published as of 2014 in western Illinois, is a direct descendant of a 19th-century Whig party news sheet, the Quincy Whig.

See also Stephen Simpson, editor of the Philadelphia Whig, a 19th-century newspaper devoted to the Whig cause.

Presidents from the Whig Party

Presidents of the United States, dates in office

- William Henry Harrison (1841)

- John Tylera (1841–45)

- Zachary Taylor (1849–50)

- Millard Fillmore (1850–53)

Additionally, John Quincy Adams, elected President as a Democratic-Republican, later became a National Republican, then a Anti-Masonic, and then a Whig after he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1831.

Presidents Abraham Lincoln, Rutherford B. Hayes, Chester A. Arthur, and Benjamin Harrison were Whigs before switching to the Republican Party, from which they were elected to office.

Candidates

| Election year | Result | Nominees | |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Vice President | ||

| 1836 | Lost | Senator Daniel Webster | Representative Francis Granger |

| Lost | Former Senator William Henry Harrison | ||

| Lost | Former Senator John Tyler | ||

| Lost | Senator Willie Person Manguma[›] | ||

| Lost | Senator Hugh Lawson White | ||

| 1840 | Won | Former Senator William Henry Harrisonb[›] | |

| 1844 | Lost | Former Senator Henry Clay | Former Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen |

| 1848 | Won | Major General Zachary Taylor b[›] | New York State Comptroller Millard Fillmore |

| 1852 | Lost | Major General Winfield Scott | Navy Secretary William Alexander Graham |

| 1856 | Lost | Former President Millard Fillmorec[›] | Former Ambassador Andrew Jackson Donelsonc[›] |

| 1860 | Lost | Former Senator John Belld[›] | Former Senator Edward Everettd[›] |

- ^ a: Although Mangum himself was a Whig, his electoral votes came from Nullificationists in South Carolina.

- ^ b: Died in office.

- ^ c: Fillmore and Donelson were also candidates on the American Party ticket.

- ^ d: Bell and Everett were also candidates on the Constitutional Union ticket.

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- American School economics and the Whigs

- History of the United States Republican Party

- List of political parties in the United States

- List of Whig National Conventions

- List of United States National Democratic/Whig Party presidential tickets

- Modern Whig Party

- Whig (British political faction)

Notes

- ^a Although Tyler was elected vice president as a Whig, his policies soon proved to be opposed to most of the Whig agenda, and he was officially expelled from the party in September 1841, five months after taking office as president.

References

- ↑ "Whigs From The Past". Modern Whig Party. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ↑ Holt (1999), p. 231.

- ↑ Holt (1999), pp. 27–30.

- ↑ Frank Towers, "Mobtown's Impact on the Study of Urban Politics in the Early Republic." Maryland Historical Magazine 107 (Winter 2012) pp: 469-75, p. 472, citing Robert E, Shalhope, The Baltimore Bank Riot: Political Upheaval in Antebellum Maryland (2009) p. 147

- 1 2 3 Alexander (1961).

- ↑ Peter Charles Hoffer (2006). The Brave New World: A History of Early America. JHU Press. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-8018-8483-2.

- ↑ David Brown, "Jeffersonian Ideology and the Second Party System." Historian 1999 62(1): 17–30.

- ↑ Holt, Michael F. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party. Oxford University Press. pp. 26–29. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, (2007) pp. 705–6

- ↑ John Mack Faragher et al. Out of Many: A History of the American People, (2nd ed. 1997) page 413

- ↑ Holt pp. 979–80.

- ↑ Donald T. Critchlow, The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History (2007) p. 103. Additional examples are of online.

- ↑ Critchlow, Donald T. "The Conservative Ascendancy: how the GOP right made political history". Harvard University Press. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Lynn Marshall. "The Strange Stillbirth of the Whig Party," American Historical Review, (1967) v. 72 pp. 445–68

- ↑ Holt (1999) p. 83

- ↑ Mark Groen, "The Whig Party and the Rise of Common Schools, 1837–1854," American Educational History Journal Spring/Summer 2008, Vol. 35 Issue 1/2, pp. 251–260

- ↑ Dominik Zaum; Christine Cheng (2011). Corruption and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding: Selling the Peace?. Routledge. p. 133.

- ↑ "The Florida Whig Party". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Is it time for a new political party?". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Thomas B. (Aug 1961). "Persistent Whiggery in the Confederate South, 1860–1877". Journal of Southern History. 27 (3): 305–329. doi:10.2307/2205211. JSTOR 2205211.

- Atkins, Jonathan M.; "The Whig Party versus the "spoilsmen" of Tennessee," The Historian, Vol. 57, 1994 online version

- Beveridge, Albert J. (1928). Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858, vol. 1, ch. 4–8.

- Brown, Thomas (1985). Politics and Statesmanship: Essays on the American Whig Party. ISBN 0-231-05602-8.

- Cole, Arthur Charles (1913). The Whig Party in the South. online version

- Foner, Eric (1970). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. ISBN 0-19-501352-2.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (Winter 1969). "Political Character, Antipartyism, and the Second Party System". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (4): 683–709. doi:10.2307/2711603. JSTOR 2711603. Online through JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. (June 1974). "Deferential-Participant Politics: The Early Republic's Political Culture, 1789–1840". American Political Science Review. American Political Science Association. 68 (2): 473–87. doi:10.2307/1959497. JSTOR 1959497. Online through JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. ISBN 0-19-503124-5.

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1960), Pulitzer prize; the standard history. Pro-Bank

- Holt, Michael F. (1992). Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln. ISBN 0-8071-2609-8.

- Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505544-6.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (1973). The American Whigs: An Anthology.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (1979). The Political Culture of the American Whigs. ISBN 0-226-35478-4.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (March 1991). "The Evangelical Movement and Political Culture during the Second Party System". Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 77 (4): 1216–39. doi:10.2307/2078260. JSTOR 2078260.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. ISBN 1-4332-6019-0.

- Kruman, Marc W. (Winter 1992). "The Second Party System and the Transformation of Revolutionary Republicanism". Journal of the Early Republic. Society for Historians of the Early American Republic. 12 (4): 509–37. doi:10.2307/3123876. JSTOR 3123876. Online through JSTOR

- Marshall, Lynn. (January 1967). "The Strange Stillbirth of the Whig Party". American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 72 (2): 445–68. doi:10.2307/1859236. JSTOR 1859236. Online through JSTOR

- McCormick, Richard P. (1966). The Second American Party System: Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era. ISBN 0-393-00680-8.

- Mueller, Henry R.; The Whig Party in Pennsylvania, (1922) online version

- Nevins, Allan. The Ordeal of the Union (1947) vol 1: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852; vol 2. A House Dividing, 1852–1857. highly detailed narrative of national politics

- Poage, George Rawlings. Henry Clay and the Whig Party (1936)

- Remini, Robert V. (1991). Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31088-4.

- Remini, Robert V. (1997). Daniel Webster. ISBN 0-393-04552-8.

- Riddle, Donald W. (1948). Lincoln Runs for Congress.

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, Jr. ed. History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2000 (various multivolume editions, latest is 2001). For each election includes good scholarly history and selection of primary documents. Essays on the most important elections are reprinted in Schlesinger, The Coming to Power: Critical presidential elections in American history (1972)

- Schurz, Carl (1899). Life of Henry Clay: American Statesmen. vol. 2.

- Shade, William G. (1983). "The Second Party System". In Paul Kleppner, et al. (contributors). Evolution of American Electoral Systems.

- Sharp, James Roger. The Jacksonians Versus the Banks: Politics in the States after the Panic of 1837 (1970)

- Silbey, Joel H. (1991). The American Political Nation, 1838–1893. ISBN 0-8047-1878-4.

- Smith, Craig R. "Daniel Webster's Epideictic Speaking: A Study in Emerging Whig Virtues" online

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. (1953). Horace Greeley, Nineteenth-Century Crusader.

- Van Deusen, Glyndon (1973). "The Whig Party". In Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. (ed.). History of U.S. Political Parties. Chelsea House Publications. pp. 1:331–63. ISBN 0-7910-5731-3.

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. Thurlow Weed, Wizard of the Lobby (1947)

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. ISBN 0-393-05820-4.

- Wilson, Major L. Space, Time, and Freedom: The Quest for Nationality and the Irrepressible Conflict, 1815–1861 (1974) intellectual history of Whigs and Democrats

Further reading

- Cole, Arthur Charles (1914). The Whig party in the South, American Historical Association, 392 pages; e'Book

- Mueller, Henry Richard (1922). The Whig Party in Pennsylvania, Columbia university, 267 pages; e'Book

- Ormsby, Robert McKinley (1859). A History of the Whig Party, Crosby, Nichols & Company, Boston, 377 pages; e'Book

- Palmerston, Viscount Henry John Temple; Crocker, John Wilson, Peel, Robert (1819). The new Whig guide, Wright, London; e'Book

- Pegg, Herbert Dale (1932). The Whig Party in North Carolina, Colonial Press, 223 pages; Book

- Smith, Ernest Anthony (1975). Whig Principles and Party Politics: Earl Fitzwilliam and the Whig Party, 1748-1833, Manchester University Press, 1975, 411 pages; ISBN 978-0-7190-0598-5; Book

- Watson, William Robinson (1844). The Whig Party: Its Objects--its Principles--its Candidates--its Duties--and Its Prospects, Knowles and Vose, Printers, 44 pages; e'Book

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whig Party (United States). |

- Whig Party in Virginia in Encyclopedia Virginia

- The American Presidency Project, contains the text of the national platforms that were adopted by the national conventions (1844–1856)

-

"Whig Party". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Whig Party". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. -

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Whig Party". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Whig Party". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

.svg.png)