Xiao'erjing

| Xiao'erjing | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 小兒經 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 小儿经 | ||||||||||

| Xiao'erjing | شِيَوْ عَر دٍ | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Children's script | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Xiao'erjin | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 小兒錦 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 小儿锦 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Xiaojing | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 小經 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 小经 | ||||||||||

| Xiao'erjing | شِيَوْ دٍ | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Children's (or Minor) script | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Xiaojing | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 消經 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 消经 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Revised script | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Chinese romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

|

|

| Yue |

| Southern Min |

| Eastern Min |

| Northern Min |

| Pu-Xian Min |

| Hainanese |

| Hakka |

| Gan |

| See also |

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

|

Xiao'erjing or Xiao'erjin or Xiaor jin or in its shortened form, Xiaojing, literally meaning "children's script" or "minor script" (cf. "original script" referring to the original Perso-Arabic script, simplified Chinese: 本经; traditional Chinese: 本經; pinyin: Běnjīng, Xiao'erjing: بٌکٍْ; Dungan: Бынҗин, Вьnⱬin), is the practice of writing Sinitic languages such as Mandarin (especially the Lanyin, Zhongyuan and Northeastern dialects) or the Dungan language in the Perso-Arabic Script.[1][2][3][4] It is used on occasion by many ethnic minorities who adhere to the Islamic faith in China (mostly the Hui, but also the Dongxiang, and the Salar), and formerly by their Dungan descendants in Central Asia. Soviet writing reforms forced the Dungan to replace Xiao'erjing with a Roman alphabet and later a Cyrillic alphabet, which they continue to use up until today.

Xiao'erjing is written from right to left, as with other writing systems using the Perso-Arabic script. The Xiao'erjing writing system is unique among Arabic script-based writing systems in that all vowels, long and short, are explicitly marked at all times with diacritics, unlike some other Arabic-based writing like the Uyghur Ereb Yéziqi which uses full letters and not diacritics to mark short vowels. This makes it a true abugida. Both of these practices are in contrast to the practice of omitting the short vowels in the majority of the languages for which the Arabic script has been adopted (like Arabic, Persian, and Urdu). This is possibly due to the overarching importance of the vowel in a Chinese syllable.

Nomenclature

Xiao'erjing does not have a single, standard name. In Shanxi, Hebei, Henan, Shandong, eastern Shaanxi and also Beijing, Tianjin, and the Northeastern provinces, the script is referred to as "Xiǎo'érjīng", which when shortened becomes "Xiǎojīng" or "Xiāojīng" (the latter "Xiāo" has the meaning of "to review" in the aforementioned regions). In Ningxia, Gansu, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, western Shaanxi and the Northwestern provinces, the script is referred to as "Xiǎo'érjǐn". The Dongxiang people refer to it as the "Dongxiang script" or the "Huihui script"; The Salar refer to it as the "Salar script"; The Dungan of Central Asia used a variation of Xiao'erjing called the "Hui script", before being made to abandon the Arabic script for Latin and Cyrillic. According to A. Kalimov, a famous Dungan linguist, the Dungan of the former Soviet Union called this script щёҗин (şjoⱬin; 消經).

Origins

Since the arrival of Islam during the Tang Dynasty (beginning in the mid-7th century), many Arabic or Persian speaking people migrated into China. Centuries later, these peoples assimilated with the native Han Chinese, forming the Hui ethnicity of today. Many Chinese Muslim students attended madrasas to study Classical Arabic and the Qur'an. Because these students had a very basic understanding of Chinese characters but would have a better command of the spoken tongue once assimilated, they started using the Arabic script for Chinese. This was often done by writing notes in Chinese to aid in the memorization of surahs. This method was also used to write Chinese translations of Arabic vocabulary learned in the madrasas. Thus, a system of writing the Chinese language with Arabic script gradually developed and standardized to some extent. Currently, the oldest known artifact showing signs of Xiao'erjing is a stone stele in the courtyard of Daxue Xixiang Mosque in Xi'an in the province of Shaanxi. The stele shows inscribed Qur'anic verses in Arabic as well as a short note of the names of the inscribers in Xiao'erjing. The stele was done in the year AH 740 in the Islamic calendar (between July 9, 1339 and June 26, 1340). Some old Xiao'erjing manuscripts (along with other rare texts including those from Dunhuang) are preserved in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Usage

Xiao'erjing can be divided into two sets, the "Mosque system", and the "Daily system". The "Mosque system" is the system used by pupils and imams in mosques and madrasahs. It contains much Arabic and Persian religious lexicon, and no usage of Chinese characters. This system is relatively standardised, and could be considered a true writing system. The "Daily system" is the system used by the less educated for letters and correspondences on a personal level. Often simple Chinese characters are mixed in with the Arabic script, mostly discussing non-religious matters, and therewith relatively little Arabic and Persian loans. This practice can differ drastically from person to person. The system would be devised by the writer himself, with one's own understanding of the Arabic and Persian alphabets, mapped accordingly to one's own dialectal pronunciation. Often, only the letter's sender and the letter's receiver can understand completely what is written, while being very difficult for others to read. Unlike Hui Muslims in other areas of China, Muslims of the northwest provinces of Shaanxi and Gansu had no knowledge of the Han Kitab or Classical Chinese, they used xiaoerjing.[5] Xiaoerjing was used to annotate in Chinese, foreign language Islamic documents in languages like Persian.[6]

Xiaojing was used mostly by Muslims who could not read Chinese characters. It was imperfect due to various factors. The differing Chinese dialects would require multiple different depictions with xiaojing. Xiaojing cannot display the tones present in Chinese, syllable endings are indistinguishable, i.e. xi'an and xian.[7] Xiaoerjing was much simpler than Chinese characters for representing Chinese.[8]

Modern usage

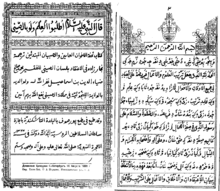

In recent years, the usage of Xiao'erjing is nearing extinction due to the growing economy of the People's Republic of China and the improvement of the education of Chinese characters in rural areas of China. Chinese characters along with Hanyu Pinyin have since replaced Xiao'erjing. Since the mid-1980s, there has been much scholarly work done within and outside China concerning Xiao'erjing. On-location research has been conducted and the users of Xiao'erjing have been interviewed. Written and printed materials of Xiao'erjing were also collected by researchers, the ones at Nanjing University being the most comprehensive. Machida Kazuhiko is leading a project in Japan concerning Xiao'erjing.[9] Books are printed in Xiao'erjing.[10] In Arabic language Qur'ans, Xiao'erjing annotations are used to help women read.[11] Xiao'erjing is used to explain certain terms when used as annotations.[12] Xiaoerjing is also used to write Chinese language Qurans.[13][14]

Alphabet

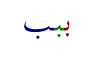

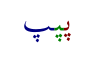

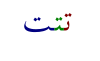

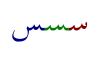

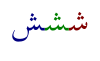

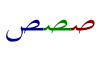

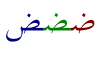

Xiao'erjing has 36 letters, 4 of which are used to represent vowel sounds. The 36 letters consists of 28 letters borrowed from Arabic, 4 letters borrowed from Persian along with 2 modified letters, and 4 extra letters unique to Xiao'erjing.

Initials and consonants

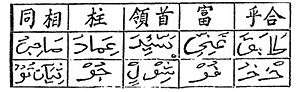

|

Finals and vowels

|

- Because there is a problem in the synthesis of the diacritical mark, and substitute the ۟ in ْ.

Vowels in Arabic and Persian loans follow their respective orthographies, namely, only the long vowels are represented and the short vowels are omitted.

Although the sukuun (![]() ) can be omitted when representing Arabic and Persian loans, it cannot be omitted when representing Chinese. The exception being that of oft-used monosyllabic words which can have the sukuun omitted from writing. For example, when emphasised, "的" and "和" are written as (دِ) and (حـَ); when unemphasised, they can be written with the sukuuns as (دْ) and (حـْ), or without the sukuuns as (د) and (حـ).

Similarly, the sukuun can also sometimes represent the Chinese -[ŋ] final instead of (ـݣ). This is sometimes replaced by the fatHatan (

) can be omitted when representing Arabic and Persian loans, it cannot be omitted when representing Chinese. The exception being that of oft-used monosyllabic words which can have the sukuun omitted from writing. For example, when emphasised, "的" and "和" are written as (دِ) and (حـَ); when unemphasised, they can be written with the sukuuns as (دْ) and (حـْ), or without the sukuuns as (د) and (حـ).

Similarly, the sukuun can also sometimes represent the Chinese -[ŋ] final instead of (ـݣ). This is sometimes replaced by the fatHatan (![]() ), the kasratan (

), the kasratan (![]() ), or the dammatan (

), or the dammatan (![]() ).

In polysyllabic words, the final 'alif (ـا) that represents the long vowel -ā can be omitted and replaced by a fatHah (

).

In polysyllabic words, the final 'alif (ـا) that represents the long vowel -ā can be omitted and replaced by a fatHah (![]() ) representing the short vowel -ă.

Xiao'erjing is similar to Hanyu Pinyin in the respect that words are written as one, while a space is inserted between words.

When representing Chinese words, the shaddah sign represents a doubling of the entire syllable on which it rests. It has the same function as the Chinese iteration mark "々".

Arabic punctuation marks can be used with Xiao'erjing as can Chinese punctuation marks, they can also be mixed (Chinese pauses and periods with Arabic commas and quotation marks).

) representing the short vowel -ă.

Xiao'erjing is similar to Hanyu Pinyin in the respect that words are written as one, while a space is inserted between words.

When representing Chinese words, the shaddah sign represents a doubling of the entire syllable on which it rests. It has the same function as the Chinese iteration mark "々".

Arabic punctuation marks can be used with Xiao'erjing as can Chinese punctuation marks, they can also be mixed (Chinese pauses and periods with Arabic commas and quotation marks).

Example

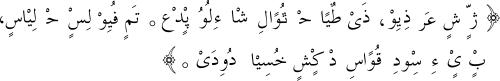

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Xiao'erjing, simplified and traditional Chinese characters, Hanyu Pinyin and English:

- Xiao'erjing:

- simplified Chinese: “人人生而自由,在尊严和权利上一律平等。他们赋有理性和良心,并应以兄弟关系的精神互相对待。”

- traditional Chinese: 「人人生而自由,在尊嚴和權利上一律平等。他們賦有理性和良心,並應以兄弟關係的精神互相對待。」

- pinyin: "Rénrén shēng ér zìyóu, zài zūnyán hé quánlì shàng yílǜ píngděng. Tāmen fùyǒu lǐxìng hé liángxīn, bìng yīng yǐ xiōngdi guānxì de jīngshén hùxiāng duìdài."

- English: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

See also

- Category:Arabic alphabets

- Islam in China

- Sini (script)

- Aljamiado

- Uyghur Arabic alphabet

References

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Howard Yuen Fung Choy (2008). Remapping the past: fictions of history in Deng's China, 1979–1997. BRILL. p. 92. ISBN 90-04-16704-8. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Daftar-i Muṭālaʻāt-i Siyāsī va Bayn al-Milalī (Iran) (2000). The Iranian journal of international affairs, Volume 12. Institute for Political and International Studies. p. 52. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Centre for the Study of Religion and Communism (2003). Religion in communist lands, Volume 31. Centre for the Study of Religion and Communism. p. 13. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Tōkyō Daigaku. Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo (2006). International journal of Asian studies, Volumes 3–5. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Geoffrey Roper (1994). World survey of Islamic manuscripts. 4. (Supplement ; including indexes of languages, names and titles of collections of volumes I-IV), Volumes 1–4. Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation. p. 96. ISBN 1-873992-11-4. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Geoffrey Roper (1994). World survey of Islamic manuscripts. 4. (Supplement ; including indexes of languages, names and titles of collections of volumes I-IV), Volumes 1–4. Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation. p. 71. ISBN 1-873992-11-4. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon (2008). Central Eurasian Reader: a biennial journal of critical bibliography and epistemology of Central Eurasian Studies, Volume 1. Schwarz. p. 12. ISBN 3-87997-347-4. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Centre for the Study of Religion and Communism (2003). Religion in communist lands, Volume 31. Centre for the Study of Religion and Communism. p. 14. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Suad Joseph, Afsaneh Najmabadi (2003). Encyclopedia of women & Islamic cultures, Volume 1. Brill. p. 126. ISBN 90-04-13247-3. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Daftar-i Muṭālaʻāt-i Siyāsī va Bayn al-Milalī (Iran) (2000). The Iranian journal of international affairs, Volume 12. Institute for Political and International Studies. p. 42. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Archives de sciences sociales des religions, Volume 46, Issues 113–116. Centre national de la recherche scientifique. 2001. p. 25. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Kees Versteegh; Mushira Eid (2005). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics: A-Ed. Brill. pp. 381–. ISBN 978-90-04-14473-6.

- A. Forke. Ein islamisches Tractat aus Turkistan // T’oung pao. Vol. VIII. 1907.

- O.I. Zavyalova. Sino-Islamic language contacts along the Great Silk Road: Chinese texts written in Arabic Script // Chinese Studies (漢學研究). Taipei: 1999. № 1.

- Xiaojing Qur'an (《小經古蘭》), Dongxiang County, Lingxia autonomous prefecture, Gansu, PRC, 1987.

- Huijiao Bizun (Xiaojing) (《回教必遵(小經)》), Islam Book Publishers, Xi'an, Shaanxi, PRC, 1993, 154 pp, photocopied edition.

- Muhammad Musa Abdulihakim. Islamic faith Q&A (《伊斯兰信仰问答》) 2nd ed. Beiguan Street Mosque, Xining, Qinghai, PRC, appendix contains a Xiao'erjing–Pinyin–Arabic comparison chart.

- Feng Zenglie. Beginning Dissertation on Xiao'erjing: Introducing a phonetic writing system of the Arabic script adopted for Chinese in The Arab World (《阿拉伯世界》) Issue #1. 1982.

- Chen Yuanlong. The Xiaojing writing system of the Dongxiang ethnicity in China's Dongxiang ethnicity (《中国东乡族》). People's Publishing House of Gansu. 1999.

External links

- Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Xiao-Er-Jin Corpus Collection and Digitization Project

- Xiao’erjin is not quite Pinyin – a blog about Xiao'erjing and related issues

- Chinese Pinyin to Xiao'erjing Online Conversion Tool