Ben Hogan

| Ben Hogan | |

|---|---|

| — Golfer — | |

|

Hogan in New York City in 1953 | |

| Personal information | |

| Full name | William Ben Hogan |

| Nickname | The Hawk, Bantam Ben, The Wee Iceman |

| Born |

August 13, 1912 Stephenville, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

July 25, 1997 (aged 84) Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Height | 5 ft 8.5 in (1.74 m) |

| Weight | 145 lb (66 kg; 10.4 st) |

| Nationality |

|

| Spouse |

Valerie Fox (1911–99) (m. 1935) |

| Career | |

| Turned professional | 1930 |

| Retired | 1971 |

| Former tour(s) | PGA Tour |

| Professional wins | 69 |

| Number of wins by tour | |

| PGA Tour | 64 (4th all time) |

| Best results in major championships (wins: 9) | |

| Masters Tournament | Won: 1951, 1953 |

| U.S. Open | Won: 1948, 1950, 1951, 1953 |

| The Open Championship | Won: 1953 |

| PGA Championship | Won: 1946, 1948 |

| Achievements and awards | |

| World Golf Hall of Fame | 1974 (member page) |

| PGA Tour leading money winner | 1940, 1941, 1942, 1946, 1948 |

| PGA Player of the Year | 1948, 1950, 1951, 1953 |

| Vardon Trophy | 1940, 1941, 1948 |

| Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year | 1953 |

| (For a full list of awards, see here) | |

William Ben Hogan (August 13, 1912 – July 25, 1997) was an American professional golfer, generally considered one of the greatest players in the history of the game.[1] Born within six months of two other acknowledged golf greats of the 20th century, Sam Snead and Byron Nelson, Hogan is notable for his profound influence on golf swing theory and his legendary ball-striking ability.

His nine career professional major championships tie him with Gary Player for fourth all-time, trailing only Jack Nicklaus (18), Tiger Woods (14) and Walter Hagen (11). He is one of only five golfers to have won all four major championships currently open to professionals (the Masters Tournament, The Open (despite only playing once), the U.S. Open, and the PGA Championship). The other four are Nicklaus, Woods, Player, and Gene Sarazen.

Early life and character

Born in Stephenville, Texas, he was the third and youngest child of Chester and Clara (Williams) Hogan. His father was a blacksmith and the family lived ten miles southwest in Dublin until 1921, when they moved 70 miles (112 km) northeast to Fort Worth. In 1922, when Hogan was nine, his father Chester committed suicide by self-inflicted gunshot at the family home. By some accounts, Chester committed suicide in front of him, which some (including Hogan biographer James Dodson) have cited as the cause of his introverted personality in later years.[2]

Following his father's suicide, the family incurred financial difficulty and the children took jobs to help their seamstress mother make ends meet. Older brother Royal quit school at age 14 to deliver office supplies by bicycle, and nine-year-old Ben sold newspapers after school at the nearby train station. A tip from a friend led him to caddying at the age of 11 at Glen Garden Country Club, a nine-hole course seven miles (11 km) to the south. One of his fellow caddies at Glen Garden was Byron Nelson, later a tour rival. The two would tie for the lead at the annual Christmas caddy tournament in December 1927, when both were 15. Nelson sank a 30-foot putt to tie on the ninth and final hole. Instead of sudden death, they played another nine holes; Nelson sank another substantial putt on the final green to win by a stroke.

The following spring, Nelson was granted the only junior membership offered by the members of Glen Garden. Club rules did not allow caddies age 16 and older, so after August 1928, Hogan took his game to three scrubby daily-fee courses: Katy Lake, Worth Hills, and Z-Boaz.

Turns professional

Hogan dropped out of Central High School (R.L. Paschal High School) during the final semester of his senior year, and became a professional golfer at the Texas Open in San Antonio in late January 1930, more than six months shy of his 18th birthday. Hogan met Valerie Fox in Sunday school in Fort Worth in the mid-1920s, and they reacquainted in 1932 when he landed a low-paying club pro job in Cleburne, where her family had moved. They married in April 1935 at her parents' home.

His early years as a pro were very difficult, and Hogan went broke more than once. He did not win his first pro tournament as an individual until March 1940, when he won three consecutive tournaments in North Carolina. Although it took a decade to secure his first victory, Hogan's wife Valerie believed in him, and this helped see him through the tough years when he battled a hook, which he later cured.

Despite finishing 13th on the money list in 1938, Hogan had to take an assistant pro job at Century Country Club in Purchase, New York. He worked at Century as an assistant and then as the head pro until 1941, when he took the head pro job at Hershey Country Club in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Career-threatening accident

Between the years of 1938 through 1959, Hogan won 63 professional golf tournaments despite his career being interrupted in its prime by World War II and a near-fatal car accident. Hogan served in the U.S. Army Air Forces from March 1943 to June 1945, becoming a utility pilot with the rank of lieutenant stationed at Fort Worth, Texas.

Hogan and his wife, Valerie, survived a head-on collision with a Greyhound bus on a fog-shrouded bridge, early in the morning, east of Van Horn, Texas on February 2, 1949. Hogan threw himself across Valerie in order to protect her, and would have been killed had he not done so, as the steering column punctured the driver's seat.

This accident left Hogan, age 36, with a double-fracture of the pelvis, a fractured collar bone, a left ankle fracture, a chipped rib, and near-fatal blood clots: he would suffer lifelong circulation problems and other physical limitations. His doctors said he might never walk again, let alone play golf competitively. While in hospital, Hogan's life was endangered by a blood clot problem, leading doctors to tie off the vena cava. Hogan left the hospital on April 1, 59 days after the accident.

After regaining his strength by extensive walking, he resumed golf activities in November 1949. He returned to the PGA Tour to start the 1950 season, at the Los Angeles Open, where he tied with Sam Snead over 72 holes, but lost the 18-hole playoff.

The "Triple Crown" season

The win at Carnoustie was only a part of Hogan's watershed 1953 season, a year in which he won five of the six tournaments he entered, including three major championships (a feat known as the Triple Crown of Golf).[3]

It still stands among the greatest single seasons in the history of professional golf. Hogan, 40, was unable to enter — and possibly win — the 1953 PGA Championship (to complete the Grand Slam) because its play (July 1–7) overlapped the play of the British Open at Carnoustie (July 6–10), which he won. It was the only time that a golfer had won three major professional championships in a year until Tiger Woods won the final three majors in 2000 (and the first in 2001).

Hogan often declined to play in the PGA Championship, skipping it more and more often as his career wore on. There were two reasons for this. First, the PGA Championship was, until 1958, a match play event, and Hogan's particular skill was "shooting a number" — meticulously planning and executing a strategy to achieve a score for a round on a particular course (even to the point of leaving out the 7-iron in the U.S. Open at Merion, saying "there are no 7-iron shots at Merion"). Second, the PGA required several days of 36 holes per day competition, and after his 1949 auto accident, Hogan struggled to manage more than 18 holes a day.

Hogan's golf swing

Ben Hogan is widely acknowledged to have been among the greatest ball strikers ever to have played golf. Although he had a formidable record as a tournament winner, it is this aspect of Hogan which mostly underpins his modern reputation.

Hogan was known to practice more than any other golfer of his contemporaries and is said to have "invented practice". On this matter, Hogan himself said, "You hear stories about me beating my brains out practicing, but... I was enjoying myself. I couldn't wait to get up in the morning, so I could hit balls. When I'm hitting the ball where I want, hard and crisply, it's a joy that very few people experience."[4] He was also one of the first players to match particular clubs to yardages, or reference points around the course such as bunkers or trees, in order to improve his distance control.

Hogan thought that an individual's golf swing was "in the dirt" and that mastering it required plenty of practice and repetition. He is also known to have spent years contemplating the golf swing, trying a range of theories and methods before arriving at the finished method which brought him his greatest period of success.

The young Hogan was badly afflicted by hooking the golf ball. Although slight of build at 5'8½" and 145 pounds[5] – attributes that earned him the nickname "Bantam", which he thoroughly disliked – he was very long off the tee early in his career, and even competed in long drive contests.

It has been alleged that Hogan used a "strong" grip, with hands more the right of the club grip in tournament play prior to his accident in 1949, despite often practicing with a "weak" grip, with the back of the left wrist facing the target, and that this limited his success, or, at least, his reliability, up to that date.[6]

Jacobs alleges that Byron Nelson told him this information, and furthermore that Hogan developed and used the "strong" grip as a boy in order to be able to hit the ball as far as bigger, stronger contemporaries. This strong grip is what resulted in Hogan hitting the odd disastrous snap hook.

Hogan's late swing produced the famed "Hogan Fade" ball flight, lower than usual for a great player and from left to right. This ball flight was the result of his using a "draw" type swing in conjunction with a "weak" grip, a combination which all but negated the chance of hitting a hook.

Hogan played and practiced golf with only bare-hands i.e. he played or practiced without wearing gloves. Moe Norman did the same, playing and practicing without gloves. The two were arguably the greatest ball strikers golf has ever known; even Tiger Woods quoted them as the only players ever to have "owned their swings", in that they had total control of it and, as a result, the ball's flight.[7]

In May 1967, the editor of Cary Middlecoff's 1974 book The Golf Swing watched every shot that 54-year-old Hogan hit in the Colonial National Invitational in Fort Worth, Texas. "Hogan shot 281 for a third-place tie with George Archer. Of the 281 shots, 141 were taken in reaching the greens. Of the 141, 139 were rated from well-executed to superbly executed. The remaining two were a drive that missed the fairway by some 5 yards and a 5-iron to a par-3 hole that missed the green by about the same distance. It was difficult, if not impossible to conceive of anybody hitting the ball better over a four-day span."[8]

Hogan's secret

Hogan is thought to have developed a "secret" which made his swing nearly automatic. There are many theories as to its exact nature. The earliest theory is that the "secret" was a special wrist movement known as "cupping under". This information was revealed in a 1955 Life magazine article. However, many believed Hogan did not reveal all that he knew at the time. It has since been alleged in Golf Digest magazine, and by Jody Vasquez in his book "Afternoons With Mr Hogan", that the second element of Hogan's "secret" was the way in which he used his right knee to initiate the swing and that this right knee movement was critical to the correct operation of the wrist.

Hogan revealed later in life that the "secret" involved cupping the left wrist at the top of the back swing and using a weaker left hand grip (thumb more on top of the grip as opposed to on the right side).

Hogan did this to prevent himself from ever hooking the ball off the tee. By positioning his hands in this manner, he ensured that the club face would be slightly open upon impact, creating a fade (left to right ball flight) as opposed to a draw or hook (right to left ball flight).

This is not something that would benefit all golfers, however, since many average golfers already slice or fade the ball. The draw is more appealing to amateurs due to its greater distance.

Many believed that although he played right-handed as an adult, Hogan was actually left-handed. In his book "Five Lessons," in the chapter entitled "The Grip," Hogan said "I was born left-handed -- that was the normal way for me to do things. I was switched over to doing things right-handed when I was a boy but I started golf as a left-hander because the first club I ever came into possession of, an old five-iron, was a left-handed stick." This belief also seemed to be corroborated by Hogan himself in his earlier book "Power Golf." However, some mystery still remains about this since Hogan in subsequent interviews said that the belief of him being left-handed was actually a myth (noted in what was probably his last video interview and in his 1987 Golf Magazine interview).

In these interviews Hogan said that he was indeed a right-handed player who early on practiced/played with a left hand club that had been given to him because it was all that he had and that it was this issue that brought about the myth that he was left-handed. This may be the reason that his early play with right-handed equipment found him using a cross-handed grip (right hand at the end of the club, left hand below it). In "The Search for the Perfect Golf Swing", researchers Cochran and Stobbs held the opinion that a left-handed person playing right-handed would be prone to hook the ball.

Iconic 1-iron shot

Hy Peskin, a staff photographer for Sports Illustrated, took an iconic photo of Ben Hogan playing a 1-iron shot to the green at the 72nd hole of the 1950 U.S. Open.[9] It was ranked by Sports Illustrated as one of the greatest sports photographs of the 20th century.[10]

"Five Lessons" and golf instruction

Hogan believed that a solid, repeatable golf swing involved only a few essential elements, which, when performed correctly and in sequence, were the essence of the swing. His book Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf (written with Herbert Warren Wind) is perhaps the most widely read golf tutorial ever written, although Harvey Penick's Little Red Book would also have a claim to that title, and the principles therein are often parroted by modern "swing gurus". In the Five Lessons, Hogan breaks down the swing into four parts: The Fundamentals, The Grip, Stance and Posture, and The Swing.

"The Fundamentals"

Hogan explains that the average golfer underestimates himself. He believes that beginners place too much emphasis on the long game. If you have a correct, powerful and repeating swing, then you can shoot in the 70s. "The average golfer is entirely capable of building a repeating swing and breaking 80."[11] Through years of trial and error, Ben has developed techniques that have proved themselves under various types of pressure.

"The Grip"

Hogan says, "Good golf begins with a good grip."[11] Without a good grip, one cannot play to his or her potential. The grip is important because it is the only direct physical contact you have with the ball via your golf club. A bad grip can cause dipping of the hands at the top of the swing and a decrease in club head speed. This can cause a loss of power and accuracy. The following describes the perfect golf grip in the eyes of Mr. Hogan:

"With the back of your left hand facing the target, place the club in the left hand so that, 1) The shaft is pressed up under the muscular pad at the inside heel of the palm, and 2) The shaft also lies directly across the top joint of the forefinger".[11]

"Crook the forefinger around the shaft and you will discover that you can lift the club and maintain a fairly firm grip on it by supporting it just with the muscles of that finger and the muscles of the pad of the palm."[11]

"Now just close the left hand-close the fingers before you close the thumb-and the club will be just where it should be."[11]

"To gain a real acquaintance with this preparatory guide to correct gripping, I would suggest practicing it five or 10 minutes a day for a week until it begins to become second nature."[11]

"To obtain the proper grip with the right hand, hold it somewhat extended, with the palm facing your target. Now-your left hand is already correctly affixed-place the club in your right hand so that the shaft lies across the top joint of the four fingers and definitely below the palm."[11]

"The right hand is a finger grip. The two fingers which should apply most of the pressure are the two middle fingers."[11]

"Now with the club held firmly on the fingers of your right hand, simply fold your right hand over your left thumb."[11]

"Stance and Posture"

The right stance not only allows for proper alignment, but also for a balanced swing, prepared usage of the proper muscles, and the maximum strength and control over your swing. We align our body to the target only after we have aligned the club head to the target.

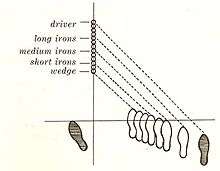

A proper stance starts with your feet being aligned at the target, followed by your knees, hips and shoulders. Your feet should be shoulder width apart, your front foot should be slightly opened towards the target and your back foot should be perpendicular to the target. As you increase in club, your stance should widen for further stability. Your shoulders will be naturally open to the target line because your arms are not at equal length while holding the club. Make sure to close your shoulders slightly to stay aligned with the target line. The proper stance affects how controlled the backswing is, governs the amount of hip turn in the backswing, and allows for the hips to clear through the downswing. Your front arm should be extended at all times to allow the club to travel in its maximum arc.

"The elbows should be tucked in, not stuck out from the body. At address, the left elbow should point directly at the left hipbone and the right elbow should point directly at the right hipbone. Furthermore, there should be a sense of fixed jointness between the two forearms and the wrists, and it should be maintained throughout the swing."[11]

"You should bend your knees from the thighs down. As your knees bend, the upper part of the trunk remains normally erect, just as it does when you sit down in a chair. In golf, the sit-down motion is more like lowering yourself onto a spectator-sports-stick. Think of the seat of the stick as being about two inches or so below your buttocks."[11]

"The Swing"

"The Backswing"

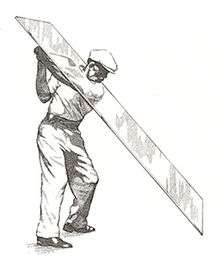

Mr. Hogan advocates the use of a waggle not only because it helps you loosen your muscles, but also because it allows for your hands and arms to remember where to go for the first part of your backswing. The angle of the swing should feel like you are swinging under a slanting plane of glass. The "glass" has a hole for your head while it rests on your shoulders and touches the ground on top of your ball. Also, the backswing should be slightly steeper than the downswing. At the top of your backswing, your back should be facing the target.

"On the backswing, the order of movement goes like this: hands, arms, shoulders, hips."[11]

"Actually, the hands start the club head back a split second before the arms start back. And the arms begin their movement a split second before the shoulders begin to turn."[11]

"Just before your hands reach hip level, the shoulders, as they turn, automatically start pulling the hips around. As the hips begin to turn, they pull the left leg in to the right."[11]

"When you have turned your shoulders all the way, your back should face squarely toward your target."[11]

"When you finish your backswing, your chin should be hitting against the top of your left shoulder."[11]

"As you begin the backswing, you must restrain your hips from moving until the turning of the shoulders starts to pull the hips around…It is this increased tension that unwinds the upper part of the body. It unwinds the shoulder, the arms and the hands in that order, the correct order. It helps the swing so much it makes it almost automatic."[11]

"If he executes his backswing properly, as his arms are approaching hip level, they should be parallel with the plane and they should remain parallel with the plane, just beneath the glass, till they reach the top of the backswing. At the top of his backswing, his left arm should be extended at the exact same angle (to the ball) as the glass."[11]

"The Downswing"

Ben believes the second part of the swing, the downswing, is initiated by the hips starting to turn. A baseball player throws a ball by transferring his weight and rotates his hips. Then his shoulders and arm follow after. Hogan thinks that the downswing is very similar to this action. The downswing is at a slightly shallower angle and therefore the arms and hands should come from the inside-out on the downswing. The club head reaches its maximum speed, not at impact, but right after, when both arms are fully extended.

"At impact the back of the left hand faces toward your target. The wrist bone is definitely raised. It points to the target and, at the moment the ball is contacted, it is out in front, nearer to the target than any part of the hand."[11]

"At impact the right arm is still bent slightly."[11]

"At that point just beyond impact where both arms are straight and extended the club head reaches its maximum speed."[11]

"The hips lead the shoulders all the way on the downswing."[11]

The Five Lessons were initially released as a five-part series in Sports Illustrated magazine, beginning with the issue of March 11, 1957.[12] It was compiled and printed in book form later that year and is currently in its 64th printing. Even today it continues to maintain a place at or near the top of the Amazon.com golf book sales rankings. The book was co-authored by Herbert Warren Wind, and illustrated by artist Anthony Ravielli.

Playing style

Hogan is widely acknowledged to have been one of the finest ball strikers that ever played the game.

Hogan's ball striking has also been described as being of near miraculous caliber by other very knowledgeable observers such as Jack Nicklaus, who only saw him play some years after his prime. Nicklaus once responded to the question, "Is Tiger Woods the best ball striker you have ever seen?" with, "No, no - Ben Hogan, easily".[13]

Further testimony to Hogan's (and Moe Norman's) status among top golfers is provided by Tiger Woods, who recently said that he wished to "own his (golf) swing" in the same way as Moe Norman and Hogan had. Woods claimed that this pair were the only players ever to have "owned their swings", in that they had total control of it and, as a result, of the ball's flight.[7]

By most accounts, Ben Hogan was the best golfer of his era, and still stands as one of the greatest of all time. "The Hawk" possessed fierce determination and an iron will, which combined with his unquestionable golf skills, formed an aura which could intimidate opponents into competitive submission. In Scotland, Hogan was known as "The Wee Ice Man", or, in some versions, "Wee Ice Mon," a moniker earned during his famous British Open victory at Carnoustie in 1953.[14] It is a reference to his steely and seemingly nerveless demeanor, itself a product of a golf swing he had built that was designed to perform better the more pressure he put it under. Hogan rarely spoke during competition, and there are numerous anecdotes about Hogan's sparse but pithy remarks. Hogan was also highly respected by fellow competitors for his superb course management skills. During his peak years, he rarely if ever attempted a shot in competition which he had not thoroughly honed in practice.

Although his ball striking was perhaps the greatest ever, Hogan is not particularly revered for his putting skills. Solid and sometimes spectacular in his early and peak years, Hogan by his later years deteriorated to the point of being an often poor putter by professional standards, particularly on slow greens. The majority of his putting problems developed after his 1949 car accident, which nearly blinded his left eye and impaired his depth perception. Toward the end of his career, he often stood over the ball inordinately long before drawing his putter back.

While he suffered from the "yips" in his later years,[15] Hogan was known as an effective putter from mid to short range on quick, U.S. Open style surfaces at times during his career.

Career and records

In 1948 alone, Ben Hogan won 10 tournaments, including the U.S. Open at Riviera Country Club, a course known as "Hogan's Alley" because of his success there. His 8-under par score in the 1948 U.S. Open set a tournament record that was matched only by Jack Nicklaus in 1980, Hale Irwin in 1990, and Lee Janzen in 1993. It was not broken until Tiger Woods shot 12-under par in the tournament in 2000 (Jim Furyk also shot 8-under par in the 2003 U.S. Open, and Rory McIlroy set the current U.S. Open record with 16-under par in 2011).

Colonial Country Club in Fort Worth, a modern PGA Tour tournament venue, is also known as "Hogan's Alley" and may have the better claim to the nickname as it was his home course after his retirement, and he was an active member of Colonial as well for many years. The sixth hole at Carnoustie, a par five on which Hogan took a famously difficult line off the tee during each of his rounds in the 1953 Open Championship, has also recently been renamed Hogan's Alley.

Prior to the 1949 accident, Hogan never truly captured the hearts of his galleries, despite being one of the best golfers of his time. Perhaps this was due to his perceived cold and aloof on-course persona. But when Hogan shocked and amazed the golf world by returning to tournament golf only 11 months after his accident, and took second place in the 1950 Los Angeles Open after a playoff loss to Sam Snead, he was cheered on by ecstatic fans. "His legs simply were not strong enough to carry his heart any longer", famed sportswriter Grantland Rice said of Hogan's near-miss. However, he proved to his critics (and to himself, especially) that he could still win by completing his famous comeback five months later, defeating Lloyd Mangrum and George Fazio in an 18-hole playoff at Merion Golf Club to win his second U.S. Open Championship.

Hogan went on to achieve what is perhaps the greatest sporting accomplishment in history, limping to 12 more PGA Tour wins (including six majors) before retiring. In 1951, Hogan entered just five events, but won three of them - the Masters, the U.S. Open, and the World Championship of Golf, and finished second and fourth in his other two starts. He would finish fourth on that season's money list, barely $6,000 behind the season's official money list leader Lloyd Mangrum, who played over 20 events. That year also saw the release of a biopic starring Glenn Ford as Hogan, called Follow the Sun: The Ben Hogan Story.[16] He even received a ticker-tape parade in New York City upon his return from winning the 1953 British Open Championship, the only time he played the event. With his British Open Championship victory, Hogan became just the second player, after Gene Sarazen, to win all four of the modern major championships—the Masters, U.S. Open, British Open, and PGA Championship.

Hogan remains the only golfer in history to win the Masters, U.S. Open, and British Open in the same calendar year (1953). His 14-under par at the 1953 Masters set a record that stood for 12 years, and he remains one of just nine golfers (Jack Nicklaus, Raymond Floyd, Ben Crenshaw, Tiger Woods, David Duval, Phil Mickelson, Charl Schwartzel and Jordan Spieth) to have recorded such a low score in the tournament. In 1967, at age 54, Hogan shot a record 30 on the back nine at the Masters; the record stood until 1992.

In 1945, Hogan set a PGA Tour record for a 72-hole event at the Portland Open Invitational by shooting 27-under-par. The record stood until 1998, when it was broken by John Huston (it has since been surpassed by nine others, including most recently Phil Mickelson's 28-under in the 2013 Waste Management Phoenix Open).[17]

Hogan never competed on the Senior PGA Tour, as that circuit did not exist until he was in his late sixties.

Five U.S. Opens?

Many supporters of Hogan and some golf historians feel that his victory at the Hale America Open in 1942 should be counted as his fifth U.S. Open and 10th major championship, since the tournament was to be a substitute for the Open after its cancellation by the USGA. The Hale America Open was held in the same time slot and was run like the U.S. Open with more than 1,500 entries, local qualifying at 69 sites and sectional qualifying at most major cities. The top players, who were not off fighting in World War II, participated and the largest purse of the year was awarded.[18][19][20]

Distinctions and honors

- Hogan played on two U.S. Ryder Cup teams, 1947 and 1951, and captained the team three times, 1947, 1949, and 1967, famously claiming on the last occasion to have brought the "twelve best golfers in the world" to play in the competition. (This line was used by subsequent Ryder Cup captain Raymond Floyd in 1989. In 1989, playing at The Belfry, the two sides halved at 14 points each and Team Europe retained the cup.)

- Hogan won the Vardon Trophy for lowest scoring average three times: 1940, 1941, and 1948. In 1953, Hogan won the Hickok Belt as the top professional athlete of the year in the United States.

- The Ben Hogan Award is given annually by the Golf Writers Association of America to a golfer who has stayed active in golf despite a physical handicap or serious illness. The first winner was Babe Zaharias.

- The Ben Hogan Award is given by Friends of Golf and the Golf Coaches Association of America to the best college golf player since 1990.

- He was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1974. In 1976, Ben Hogan was voted the Bob Jones Award, the highest honor given by the United States Golf Association in recognition of distinguished sportsmanship in golf.

- A special room is dedicated to Hogan's career, comeback, and accomplishments at the United States Golf Association Museum and Arnold Palmer Center for Golf History in Far Hills, New Jersey.

- Hogan ranked 38th in ESPN's SportsCentury 50 Greatest Athletes of the 20th Century in 1999.

- In 2000, Hogan was ranked as the second greatest player of all time by Golf Digest magazine. Jack Nicklaus was first, and Sam Snead was third.[21]

- In 2009, Hogan was ranked as the fourth greatest player of all time by Golf Magazine. Jack Nicklaus was first, Tiger Woods was second, and Bobby Jones was third.[22]

- Hogan helped to design the original plans for the Trophy Club Country Club Golfcourse in Trophy Club, Texas, and 9 of the course's 18 holes are designated as the "Hogan" Course.

Ben Hogan Golf Company

Following his most successful season, Hogan started his golf club company in the fall of 1953 in Fort Worth. Production began in the summer of 1954, with clubs targeted toward "the better player." Always a perfectionist, Hogan is said to have ordered the entire first production run of clubs destroyed because they did not meet his exacting standards.

In 1960, he sold the company to American Machine and Foundry (AMF), but stayed on as chairman of the board for several more years. AMF Ben Hogan golf clubs were sold continuously from 1960 to 1985 when AMF was bought by Minstar who sold The Ben Hogan company in 1988 to Cosmo World, who owned the club manufacturer until 1992, when it was sold to another independent investor, Bill Goodwin.

Goodwin moved the company out of Fort Worth, and a union shop, to Virginia so it would be close to his home of operations for other AMF brands and, incidentally, a non-union shop in an effort to return the company to profitability. Goodwin sold to Spalding in 1997, closing the sale in January 1998. Spalding returned manufacturing to Hogan's Fort Worth, Texas roots before eventually including the company's assets in a bankruptcy sale of Spalding's Topflite division to Callaway in 2004. Callaway now owns the rights to the Ben Hogan brand. After over a half century and numerous ownership changes, the Ben Hogan line was discontinued by Callaway in 2008. In May 2014, Terry Koehler of Eldolon Brands approached Perry Ellis International and got the rights to use Ben Hogan's name for a line of golf clubs.[23]

Ownership timeline

- 1953 – company founded

- 1960 – sold to AMF, Hogan retained as president

- 1984 – sold to Irwin Jacobs for $15 million

- 1988 – sold to Cosmo World of Japan for $55 million, initial sponsor of the Ben Hogan Tour from 1990–92

- 1992 – sold to Bill Goodwin of Richmond, Virginia

- 1997 – sold to Spalding Top-Flite[24]

- 2003 – sold to Callaway Golf, Hogan line discontinued in 2008

- 2014 - name purchased by Eldolon for a revived Ben Hogan line

Death

Hogan died in Fort Worth, Texas on July 25, 1997 at the age of 84, and is interred at Greenwood Memorial Park there.

Professional wins

PGA Tour wins (64)

- 1938 (1) Hershey Four-Ball (with Vic Ghezzi)

- 1940 (4) North and South Open, Greater Greensboro Open, Asheville Land of the Sky Open, Goodall Palm Beach Round Robin

- 1941 (5) Asheville Open, Chicago Open, Hershey Open, Miami Biltmore International Four-Ball (with Gene Sarazen), Inverness Invitational Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret)

- 1942 (6) Los Angeles Open, San Francisco Open, North and South Open, Asheville Land of the Sky Open, Hale America Open, Rochester Open

- 1945 (5) Nashville Invitational, Portland Open Invitational, Richmond Invitational, Montgomery Invitational, Orlando Open

- 1946 (13) Phoenix Open, San Antonio Texas Open, St. Petersburg Open, Miami International Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret), Colonial National Invitation, Western Open, Goodall Round Robin, Inverness Invitational Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret), Winnipeg Open, PGA Championship, Golden State Open, Dallas Invitational, North and South Open

- 1947 (7) Los Angeles Open, Phoenix Open, Colonial National Invitation, Chicago Victory Open, World Championship of Golf, Miami International Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret), Inverness Invitational Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret)

- 1948 (10) Los Angeles Open, PGA Championship, U.S. Open, Inverness Invitational Four-Ball (with Jimmy Demaret), Motor City Open, Reading Open, Western Open, Denver Open, Reno Open, Glendale Open

- 1949 (2) Bing Crosby Pro-Am, Long Beach Open

- 1950 (1) U.S. Open

- 1951 (3) Masters Tournament, U.S. Open, World Championship of Golf

- 1952 (1) Colonial National Invitation

- 1953 (5) Masters Tournament, Pan American Open, Colonial National Invitation, U.S. Open, The Open Championship

- 1959 (1) Colonial National Invitation

Major championships are shown in bold.

Source: (Barkow 1989, pp. 261–262)

Other wins (5)

this list is probably incomplete

- 1940 Westchester Open, Westchester PGA Championship

- 1950 Greenbrier Pro-Am

- 1956 World Cup of Golf individual; World Cup of Golf team

Major championships

Wins (9)

| Year | Championship | 54 holes | Winning score | Margin | Runner(s)-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | PGA Championship | n/a | 6 & 4 | n/a | |

| 1948 | PGA Championship (2) | n/a | 7 & 6 | n/a | |

| 1948 | U.S. Open | 2 shot lead | −8 (67-72-68-69=276) | 2 strokes | |

| 1950 | U.S. Open (2) | 2 shot deficit | +7 (72-69-72-74=287) | Playoff 1 | |

| 1951 | Masters Tournament | 1 shot deficit | −8 (70-72-70-68=280) | 2 strokes | |

| 1951 | U.S. Open (3) | 2 shot deficit | +7 (76-73-71-67=287) | 2 strokes | |

| 1953 | Masters Tournament (2) | 4 shot lead | −14 (70-69-66-69=274) | 5 strokes | |

| 1953 | U.S. Open (4) | 1 shot lead | −5 (67-72-73-71=283) | 6 strokes | |

| 1953 | The Open Championship | Tied for lead | −6 (73-71-70-68=282) | 4 strokes |

Note: The PGA Championship was match play until 1958

1 Defeated Mangrum and Fazio in 18-hole playoff: Hogan 69 (-1), Mangrum 73 (+3), Fazio 75 (+5).

Results timeline

| Tournament | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | T25 | 9 |

| U.S. Open | CUT | DNP | CUT | DNP | CUT | T62 |

| The Open Championship | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| PGA Championship | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | R16 |

| Tournament | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | T10 | 4 | 2 | NT | NT | NT | 2 | T4 | T6 | DNP |

| U.S. Open | T5 | T3 | NT | NT | NT | NT | T4 | T6 | 1 | DNP |

| The Open Championship | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| PGA Championship | QF | QF | QF | NT | DNP | DNP | 1 | R64 | 1 | DNP |

| Tournament | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | T4 | 1 | T7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | T8 | CUT | T14 | T30 |

| U.S. Open | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | T6 | 2 | T2 | DNP | T10 | T8 |

| The Open Championship | DNP | DNP | DNP | 1 | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| PGA Championship | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| Tournament | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | T6 | T32 | 38 | DNP | T9 | T21 | T13 | T10 |

| U.S. Open | T9 | T14 | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | 12 | T34 |

| The Open Championship | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| PGA Championship | CUT1 | DNP | DNP | DNP | T9 | T15 | DNP | DNP |

NT = No tournament

DNP = Did not play

WD = Withdrew

CUT = missed the half-way cut

R64, R32, R16, QF, SF = Round in which player lost in PGA Championship match play

"T" indicates a tie for a place

Green background for wins. Yellow background for top-10.

1 missed 54-hole cut at 1960 PGA Championship

Summary

| Tournament | Wins | 2nd | 3rd | Top-5 | Top-10 | Top-25 | Events | Cuts made |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | 2 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 17 | 21 | 25 | 24 |

| U.S. Open | 4 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 15 | 17 | 22 | 19 |

| The Open Championship | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PGA Championship | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 9 |

| Totals | 9 | 6 | 2 | 25 | 40 | 47 | 58 | 53 |

- Most consecutive cuts made – 35 (1939 Masters – 1956 U.S. Open)

- Longest streak of top-10s – 18 (1948 Masters – 1956 U.S. Open)

U.S. national team appearances

Professional

- Ryder Cup: 1947 (winners, playing captain), 1949 (winners, non-playing captain), 1951 (winners), 1967 (winners, non-playing captain)

- Canada Cup: 1956 (winners, individual winner), 1958

See also

- Career Grand Slam Champions

- List of golfers with most PGA Tour wins

- List of men's major championships winning golfers

- List of golfers with most wins in one PGA Tour event

- Longest PGA Tour win streaks

- Most PGA Tour wins in a year

References

- ↑ Golf Legends - Ben Hogan Archived May 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Hard Life of a Golfing Great". Bloomberg Businessweek. June 18, 2004. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Ben Hogan's Triple Crown". The Augusta Chronicle. February 15, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Apfelbaum, Jim, ed. (2007). The Gigantic Book of Golf Quotations. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-014-0.

- ↑ Elliott, Len; Kelly, Barbara (1976). Who's Who in Golf. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House. pp. 93–4. ISBN 0-87000-225-2.

- ↑ Jacobs, John (2000). Fifty Greatest Golf Lessons of the Century. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0062716149.

- 1 2 Golf Digest, January 2005

- ↑ Middlecoff, Cary (1974). Michael, Tom, ed. The Golf Swing. Prentice-Hall. p. 32. ASIN B000N6ZBEQ.

- ↑ Politi, Steve. "Ben Hogan made U.S. Open history with the 1 iron, but the club has vanished from golf". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ Wanke, Michele. "Sports Illustrated Photo Pioneers". LoveToKnow. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Hogan, Ben (1957). Ben Hogan's Five Lessons. Fireside. ISBN 0-671-61297-2.

- ↑ Hogan, Ben (March 11, 1957). "The modern fundamentals of golf: the grip". Sports Illustrated.

- ↑ Golf Digest, April 2004

- ↑ "1953 Ben Hogan". The Open. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ↑ Wagner, James (March 13, 2009). "Are the yips more than something in the head?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009.

- ↑ Follow the Sun - Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Kelly, Brent. "PGA Tour Scoring Record – Most Strokes Under Par Over 72 Holes". About.com. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ↑ McAfee, James (June 6, 2011). "Did Ben Hogan Win Five U.S. Opens?". Exegolf magazine. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ↑ Hanley, Reid (June 16, 1992). "Hale America: A U.S. Open?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ↑ Alvarez, Rob (June 23, 2011). "Museum Moment: The Hale America National Open Golf Tournament". USGA Museum. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ↑ Yocom, Guy (July 2000). "50 Greatest Golfers of All Time: And What They Taught Us". Golf Digest. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ↑ Golf Magazine, September 2009.

- ↑ Wall, Jonathan (May 20, 2014). "Return of a legendary brand". PGA Tour.

- ↑ Rovell, Darren (August 12, 2003). "Legendary brand will soon have new owner - again". ESPN. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

Further reading

- Barkow, Al (1989). The History of the PGA TOUR. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-26145-4.

- "Ben Hogan: "Players Were Afraid"" (1999). In ESPN SportsCentury. Michael MacCambridge, Editor. New York: Hyperion ESPN Books. pp. 142–3.

- Dodson, James (2004). Ben Hogan: An American Life. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50312-1.

- McLean, Jim; McCarthy, Tom (2012). The Complete Hogan. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-87624-4.

External links

- Ben Hogan's official site

- Ben Hogan - Daily Telegraph obituary

- World Golf Hall of Fame profile

- Ben Hogan Photos by A Ravielli Taken For The 5 Lessons of Golf

- Ben Hogan on About.com Profile, stats and quotes

- Ben Hogan at Find a Grave