Nagaland

| Nagaland | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | ||

| ||

| ||

| Coordinates (Kohima): 25°40′N 94°07′E / 25.67°N 94.12°ECoordinates: 25°40′N 94°07′E / 25.67°N 94.12°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Formation | 1 December 1963† | |

| Capital | Kohima | |

| Largest city | Dimapur | |

| Districts | 11 | |

| Government | ||

| • Governor | Padmanabha Acharya | |

| • Chief Minister | T. R. Zeliang (NPF) | |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (60 seats) | |

| • Parliamentary constituency |

Rajya Sabha 1 Lok Sabha 1 | |

| • High Court | Gauhati High Court – Kohima Bench | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 16,579 km2 (6,401 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 26th | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Total | 1,980,602 | |

| • Rank | 25th | |

| • Density | 119/km2 (310/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+05:30) | |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-NL | |

| HDI |

| |

| HDI rank | 4th (2005) | |

| Literacy | 80.11% (13th) | |

| Official language | English | |

| Website | nagaland.nic.in | |

| †It was carved out from the state of Assam by the State of Nagaland Act, 1962 | ||

| Animal | Methun |

|---|---|

| Bird | Blyth's tragopan (Tragopan blythii) |

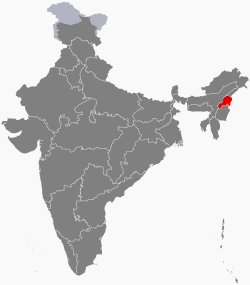

Nagaland /ˈnɑːɡəlænd/ is a state in Northeast India. It borders the state of Assam to the west, Arunachal Pradesh and part of Assam to the north, Burma to the east, and Manipur to the south. The state capital is Kohima, and the largest city is Dimapur. It has an area of 16,579 square kilometres (6,401 sq mi) with a population of 1,980,602 per the 2011 Census of India, making it one of the smallest states of India.[1]

The state is inhabited by 17 major tribes — Ao, Angami, Chang, Konyak, Lotha, Sumi, Chakhesang, Khiamniungan, Dimasa Kachari, Phom, Rengma, Sangtam, Yimchunger, Kuki, Zeme-Liangmai (Zeliang) Pochury and Rongmei as well as sub-tribes.[2] Each tribe is unique in character with its own distinct customs, language and dress.[3]

Two threads common to all are language and religion. English is in predominant use. Nagaland is one of three states in India where the population is mostly Christian.[4][5]

Nagaland became the 16th state of India on 1 December 1963. Agriculture is the most important economic activity and the principal crops include rice, corn, millets, pulses, tobacco, oilseeds, sugarcane, potatoes, and fibres. Other significant economic activity includes forestry, tourism, insurance, real estate, and miscellaneous cottage industries.

The state has experienced insurgency as well as inter-ethnic conflict since the 1950s. The violence and insecurity have long limited Nagaland's economic development, because it had to commit its scarce resources on law, order, and security.[6][7] In the last 15 years, the state has seen less violence and annual economic growth rates nearing 10% on a compounded basis: one of the fastest in the region.[8]

The state is mostly mountainous except those areas bordering Assam valley. Mount Saramati is the highest peak at 3,840 metres and its range forms a natural barrier between Nagaland and Burma.[9] It lies between the parallels of 98 and 96 degrees east longitude and 26.6 and 27.4 degrees latitude north. The state is home to a rich variety of flora and fauna; it has been suggested as the "falcon capital of the world."[10]

History

The ancient history of the Nagas is unclear. Some anthropologists suggest Nagas belong to the Mongoloid race, and tribes migrated at different times, each settling in the northeastern part of present India and establishing their respective sovereign mountain terrains and village-states. There are no records of whether they came from the northern Mongolian region, southeast Asia or southwest China, except that their origins are from the east of India and that historic records show the present-day Naga people settled before the arrival of the Ahoms in 1228 AD.[3][6]

The origin of the word ‘Naga' is also unclear.[3] A popularly accepted, but controversial, view is that it originated from the Burmese word ‘naka’, meaning people with earrings. Others suggest it means pierced noses.[11]

Before the arrival of European colonialism in South Asia, there had been many wars, persecution and raids from Burma on Naga tribes, Meitei people and others in India's northeast. The invaders came for "head hunting" and to seek wealth and captives from these tribes and ethnic groups. When the British inquired Burmese guides about the people living in northern Himalayas, they were told ‘Naka’. This was recorded as ‘Naga’ and has been in use thereafter.[3][7]

With the arrival of British East India Company in the early 19th century, followed by the British Raj, Britain expanded its domain over entire South Asia including the Naga Hills. The first Europeans to enter the hills were Captains Jenkins and Pemberton in 1832. The early contact with the Naga tribes were of suspicion and conflict. The colonial interests in Assam, such as tea estates and other trading posts suffered from raids from tribes who were known for their bravery and "head hunting" practices. To put an end to these raids, the British troops recorded 10 military expeditions between 1839 and 1850.[3] In February 1851, at the bloody battle at Kikrüma, people died on the British and the Kikrüma Naga tribe side; in days after the battle, intertribal warfare followed that led to more bloodshed. After that war, the British first adopted a policy of respect and non-interference with Naga tribes. This policy failed.

Over 1851 to 1865, Naga tribes continued to raid the British in Assam. The British India Government, fresh from the shocks of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, reviewed its governance structure throughout South Asia including its northeastern region. In 1866, the British India administration reached the historic step in Nagaland's modern history, by establishing a post at Samaguting with the explicit goal of ending intertribal warfare and tribal raids on property and personnel.[6][7] In 1869, Captain Butler was appointed to lead and consolidate the British presence in the Nagaland Hills. In 1878, the headquarters were transferred to Kohima — creating a city that remains an important centre of administration, commerce and culture for Nagaland.[3]

On 4 October 1879, GH Damant (M.A.C.S), a British political agent, went to Khonoma with troops, where he was shot dead with 35 of his team.[12] Kohima was next attacked and the stockade looted. This violence led to a determined effort by the British Raj to return and respond. The subsequent defeat of Khonoma marked the end of serious and persistent hostility in the Naga Hills.[3]

Between 1880 and 1922, the British administration consolidated their position over a large area of the Naga Hills and integrated it into its Assam operations. The British administration enforced the rupee as the currency for economic activity and a system of structured tribal government that was very different than historic social governance practices.[6] These developments triggered profound social changes among the Naga people.

In parallel, since mid-19th century, Christian missionaries from the United States and Europe, stationed in India,[13] reached into Nagaland and neighbouring states, playing their role in converting Nagaland's Naga tribes from Animism to Christianity.[6][14]

20th century

In 1944, the Indian National Army with the help of Japanese Army, led by Netaji Subhashchandra Bose, invading through Burma, attempted to free India through Kohima. The population was evacuated. British India soldiers defended the area of Kohima and were relieved by British in June 1944, having lost many of their original force. Indian National Army lost half their numbers, many through starvation, and were forced to withdraw through Burma.[15][16]

National wakening yet eventual road to statehood within India

In 1929, a Memorandum was submitted to the Simon Statutory Commission, requesting that the Nagas be exempt from reforms and new taxes proposed in British India, should be left alone to determine their own future.[17] This Naga Memorandum stated,

Before the British Government conquered our country in 1879-80, we were living in a state of intermittent warfare with the Assamese of the Assam valley to the North and West of our country and Manipuris to the South. They never conquered us nor were we subjected to their rules. On the other hand, we were always a terror to these people. Our country within the administered area consists of more than eight regions quite different from one another, with quite different languages which cannot be understood by each other, and there are more regions outside the administered area which are not known at present. We have no unity among us and it is only the British Government that is holding us together now. Our education is poor. (...) Our country is poor and it does not pay for any administration. Therefore if it is continued to be placed under Reformed Scheme, we are afraid new and heavy taxes will have to be imposed on us, and when we cannot pay, then all lands have to be sold and in long run we shall have no share in the land of our birth and life will not be worth living then. Though our land at present is within the British territory, Government have always recognised our private rights in it, but if we are forced to enter the council the majority of whose number is sure to belong to other districts, we also have much fear the introduction of foreign laws and customs to supersede our own customary laws which we now enjoy.— Naga Memorandum to Simon Commission, British India, 1929[18]

From 1929 to 1935, the understanding of sovereignty by Nagas was ‘self-rule’ based on traditional territorial definition. From 1935 to 1945, Nagas were merely asking for autonomy within Assam. In response to the Naga memorandum to Simon Commission, the British House of Commons decreed that the Naga Hills ought to be kept outside the purview of the New Constitution; the Government of India Act, 1935 and ordered Naga areas as Excluded Area; meaning outside the administration of British India government. Thereafter from 1 April 1937, it was brought under the direct administration of the Crown through Her Majesty’s representative; the Governor of Assam province.

The Naga Memorandum submitted by the Naga Club (which later became the Naga National Council) to the Simon Commission explicitly stated, 'to leave us alone to determine ourselves as in ancient times.'[18] In February 1946, the Naga Club officially took shape into a unified Naga National Council in Wokha. In June 1946, the Naga National Council submitted a four-point memorandum to officials discussing the independence of India from British colonial rule. The memorandum strongly protested against the grouping of Assam with Bengal and asserted that Naga Hills should be constitutionally included in an autonomous Assam, in a free India, with local autonomy, due safeguards and separate electorate for the Naga tribes.

Jawaharlal Nehru replied to the memorandum and welcomed the Nagas to join the Union of India promising local autonomy and safeguards. On 9 April 1946, the Naga National Council (NNC) submitted a memorandum to the British Cabinet Mission during its visit to Delhi. The crux of the memorandum stated that: “Naga future would not be bound by any arbitrary decision of the British Government and no recommendation would be accepted without consultation”.

In June 1946, the NNC submitted a four-point memorandum signed by T. Sakhrie; the then Secretary of NNC, to the still-visiting British Cabinet Mission. The memorandum stated that: 1. The NNC stands for the solidarity of all Naga tribes, including those in un-administered areas; 2. The Council protests against the grouping of Assam with Bengal; 3. The Naga Hills should be constitutionally included in an autonomous Assam, in a free India, with local autonomy and due safeguards for the interests of the Nagas; 4. The Naga tribes should have a separate electorate.

On 1 August 1946, Nehru, President of the Indian National Congress Party in his reply to the memorandum, appealed to the Nagas to join the Union of India promising local autonomy and safeguards in a wide ranging areas of administration. It was after 1946 only that the Nagas had asserted their inalienable right to be a separate nation and an absolute right to live independently.

After the independence of India in 1947, the area remained a part of the province of Assam. Nationalist activities arose amongst a section of the Nagas. Phizo-led Naga National Council and demanded a political union of their ancestral and native groups. The movement led to a series of violent incidents, that damaged government and civil infrastructure, attacked government officials and civilians. The union government sent the Indian Army in 1955, to restore order. In 1957, an agreement was reached between Naga leaders and the Indian government, creating a single separate region of the Naga Hills. The Tuensang frontier was united with this single political region, Naga Hills Tuensang Area (NHTA),[19] and it became a Union territory directly administered by the Central government with a large degree of autonomy. This was not satisfactory to the tribes, however, and agitation with violence increased across the state – including attacks on army and government institutions, banks, as well as non-payment of taxes. In July 1960, following discussion between Prime Minister Nehru and the leaders of the Naga People Convention (NPC), a 16-point agreement was arrived at whereby the Government of India recognised the formation of Nagaland as a full-fledged state within the Union of India.[20]

Accordingly, the territory was placed under the Nagaland Transitional Provisions Regulation, 1961[21] which provided for an Interim body consisting of 45 members to be elected by tribes according to the customs, traditions and usage of the respective tribes. Subsequently, Nagaland attained statehood with the enactment of the state of Nagaland Act in 1962[22] by the Parliament. The interim body was dissolved on 30 November 1963 and the state of Nagaland was formally inaugurated on 1 December 1963 and Kohima was declared as the state capital. After elections in January 1964, the first democratically elected Nagaland Legislative Assembly was constituted on 11 February 1964.[19][23]

The rebel activity continued, in the form of banditry and attacks, motivated more by tribal rivalry and personal vendetta than by political aspiration. Cease-fires were announced and negotiations continued, but this did little to stop the violence. In March 1975, direct presidential rule was imposed by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on the state. In November 1975, the leaders of largest rebellion groups agreed to lay down their arms and accept the Indian constitution, a small group did not agree and continued their insurgent activity.[24] The Nagaland Baptist Church Council played an important role by initiating peace efforts in 1960s.[3] This took concrete and positive shape during its Convention in early 1964. It formed the Nagaland Peace Council in 1972. However, these efforts have not completely ended the inter-factional violence. In 2012, the state's leaders approached Indian central government to seek a political means for a lasting peace within the state.[25]

Over the 5-year period of 2009 to 2013, between 0 and 11 civilians died per year in Nagaland from rebellion related activity (or less than 1 death per 100,000 people), and between 3 and 55 militants deaths per year in inter-factional killings (or between 0 and 3 deaths per 100,000 people).[26] The world's average annual death rate from intentional violence, in recent years, has been 7.9 per 100,000 people.[27] The most recent Nagaland Legislative Assembly election took place on 23 February 2013 to elect the Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from each of the 60 Assembly Constituencies in the state. Nagaland People's Front was elected to power with 37 seats.[28]

Battle of Kohima

.jpeg)

In 1944 during World War II, along with Manipur, British and Indian troops in Nagaland successfully repelled Japanese troops in Battle of Kohima.[29] The battle was fought from 4 April to 22 June 1944 from the town of Kohima, coordinated with action from Imphal, Manipur.[30][31]

There is the World War II Cemetery, and the War Museum, in honour of those who lost their lives during World War II during the fighting between British Empire and Japanese troops. Nearly 4,000 British Empire troops lost their lives, along with 3,000 Japanese. Many of those who lost their lives were Naga people, particularly of Angami tribe. Near the memorial is the Kohima Cathedral, on Aradura hill, built with funds from the families and friends of deceased Japanese soldiers. Prayers are held in Kohima for peace and in memory of the fallen of both sides of the battle.[32][33]

Historical rituals

Historically, Naga tribes celebrated two main rituals. These were feasting and head hunting.

Head hunting

Head hunting, a male activity, would involve separating men from their women before, during and after coming back from an expedition. The women, as a cultural practice, would encourage men to undertake head-hunting as a prerequisite to marriage. The men would go on an expedition against other tribes or neighbouring kingdoms, and kill to score number of heads they were able to hunt. A successful head hunter would be conferred a right to ornaments. The practice of head hunting was banned in 19th century India, and is no longer practised among Naga people.[3]

Feasts of Merit

In Naga society, individuals were expected to find their place in the social hierarchy, and prestige was the key to maintaining or increasing social status. To achieve these goals a man, whatever his ascendancy, had to be a headhunter or great warrior, have many conquests among women sex, or complete a series of merit feasts.[34]

The Feasts of Merit reflected the splendor and celebration of Naga life.[6] Only married men could give such Feasts, and his wife took a prominent and honoured place during the ritual which emphasised male-female co-operation and interdependence. His wife brewed the beer which he offered to the guests. The event displayed ceremonies and festivities organised by the sponsor. The Feast given by a wealthier tribes person would be more extravagant.[35] He would typically invite everyone from the tribe. This event bestowed honour to the couple from the tribe. After the Feast, the tribe would give the couple rights to ornaments equally.[6][36]

Geography

Nagaland is largely a mountainous state. The Naga Hills rise from the Brahmaputra Valley in Assam to about 2,000 feet (610 m) and rise further to the southeast, as high as 6,000 feet (1,800 m). Mount Saramati at an elevation of 12,601.70 feet (3,841.00 m) is the state's highest peak; this is where the Naga Hills merge with the Patkai Range in which form the boundary with Burma. Rivers such as the Doyang and Diphu to the north, the Barak river in the southwest, dissect the entire state. 20 percent of the total land area of the state is covered with wooded forest, a haven for flora and fauna. The evergreen tropical and the sub tropical forests are found in strategic pockets in the state.[37]

Climate

Nagaland has a largely monsoon climate with high humidity levels. Annual rainfall averages around 70–100 inches (1,800–2,500 mm), concentrated in the months of May to September. Temperatures range from 70 °F (21 °C) to 104 °F (40 °C). In winter, temperatures do not generally drop below 39 °F (4 °C), but frost is common at high elevations. The state enjoys a salubrious climate. Summer is the shortest season in the state that lasts for only a few months. The temperature during the summer season remains between 16 °C (61 °F) to 31 °C (88 °F). Winter makes an early arrival and bitter cold and dry weather strikes certain regions of the state. The maximum average temperature recorded in the winter season is 24 °C (75 °F). Strong northwest winds blow across the state during the months of February and March.[38]

Flora and fauna

About one-sixth of Nagaland is covered by tropical and sub-tropical evergreen forests—including palms, bamboo, rattan as well as timber and mahogany forests. While some forest areas have been cleared for jhum cultivation, many scrub forests, high grass, reeds; secondary dogs, pangolins, porcupines, elephants, leopards, bears, many species of monkeys, sambar, harts, oxen, and buffaloes thrive across the state's forests. The great Indian hornbill is one of the most famous birds found in the state. Blyth's tragopan, a vulnerable species of pheasant, is the state bird of Nagaland. It is sighted in Mount Japfü and Dzükou Valley of Kohima district, Satoi range in Zunheboto district and Pfütsero in Phek district. Of the mere 2500 tragopans sighted in the world, Dzükou valley is the natural habitat of more than 1,000.[39]

Mithun (a semi domesticated gaur) found only in the north-eastern states of India, is the state animal of Nagaland and has been adopted as the official seal of the Government of Nagaland. It is ritually the most valued species in the state. To conserve and protect this animal in the northeast, the National Research Centre on Mithun (NRCM) was established by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) in 1988.[40]

Geology

Several preliminary studies indicate significant recoverable reserves of petroleum and natural gas.[2]

Demographics

Population

The population of Nagaland is nearly two million people, of which 1.04 million are males and 0.95 million females.[3] Among its districts, Dimapur has the largest population (379,769), followed by Kohima (270,063). The least populated district is Longleng (50,593). 75% of the population lives in the rural areas. As of 2013, about 10% of rural population is below the poverty line; among the people living in urban areas 4.3% of them are below the poverty line.[41]

| Population change | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1951 | 213,000 | — | |

| 1961 | 369,000 | 73.2% | |

| 1971 | 516,000 | 39.8% | |

| 1981 | 775,000 | 50.2% | |

| 1991 | 1,210,000 | 56.1% | |

| 2001 | 1,990,000 | 64.5% | |

| 2011 | 1,980,602 | -0.5% | |

| Source:Census of India[42] | |||

The state showed a population drop between 2001 census to 2011 census, the only state to show a population drop in the census. This has been attributed, by scholars,[43] to incorrect counting in past censuses; the 2011 census in Nagaland is considered most reliable so far.[44]

Languages

Per Grierson's classification system, Naga languages can be grouped into Western, Central and Eastern Naga Groups. The Western Group includes among others Angami, Chokri[48] and Kheza. The Central Naga group includes Ao, Sumi, Lotha and Sangtam, whereas Eastern Group includes Konyak and Chang.[49] In addition, there are Naga-Bodo group illustrated by Mikir language, and Kuki group of languages illustrated by Sopvama (also called Mao Naga) and Luppa languages. These belong mostly[6] to the Sino-Tibetan language family.[50] Shafer came up with his own classification system for languages found in and around Nagaland.[49] Each tribe has one or more dialects that are unintelligible to others.

In 1967, the Nagaland Assembly proclaimed English as the official language of Nagaland and it is the medium for education in Nagaland. Other than English, Nagamese, a creole language form of Indo-Aryan Assamese, is a widely spoken language.[51]

The major languages spoken as per 2001 census are Ao (257,500), Konyak (248,002), Lotha (168,356), Angami (131,737), Sumi (123,884) Phom (122,454), Yimchungre (92,092), Sangtam (84,150), Chakru (83,506), Chang (62,347), Zeliang (61,492), Bengali (58,890), Rengma (58,590), Hindi (56,981), Kheza (40,362), Khiamniungan (37,752), Kuki (19,768), Assamese (16,183), and Chakhesang (9,544).

Religion

The state's population is 1.978 million, out of which 88% are Christians.[54][55] The census of 2011 recorded the state's Christian population at 1,739,651, making it, with Meghalaya, and Mizoram one of the three Christian-majority states in India. The state has a very high church attendance rate in both urban and rural areas. Huge churches dominate the skylines of Kohima, Dimapur, and Mokokchung.

Nagaland is known as "the only predominantly Baptist state in the world" and "the most Baptist state in the world"[56][57][58] Among Christians, Baptists have constituted more than 75% of the state's population, thus making it more Baptist (on a percentage basis) than Mississippi in the southern United States, where 55% of the population is Baptist, and Texas which is 51% Baptist.[59][60] Roman Catholics, Revivalists, and Pentecostals are the other Christian denomination numbers. Catholics are found in significant numbers in parts of Wokha district and Kohima district as well as in the urban areas of Kohima and Dimapur.

Christianity arrived in Nagaland in early 19th century. The American Baptist Naga mission grew out of Assam mission in 1836. Miles Bronson, Nathan Brown and others in Christian missionaries working out of Jaipur, to bring Christianity into Indian subcontinent, saw the opportunity for gaining converts since India's northeast was principally Animist and folk religion driven. Along with other tribal regions of the northeast, Nagaland people accepted Christianity.[13] However, the conversions have been marked by high rates of re-denomination ever since. After having converted to Christianity, people do not feel bound to any one sect, switch affiliation between denominations. According to a 2007 report,[55] breakaway churches are constantly being established alongside older sects. These new Christian churches differ from older ones in terms of their liturgical traditions and methods of worship. The younger churches exhibit a more vocally explicit form of worship. The Constitution of India grants all citizens, including Nagaland people, a freedom to leave, change or adopt any religion and its new sects.

Hinduism, Islam and Jainism are also found in Nagaland. They are minority religions in the state, at 8.75%, 2.47% and 0.13% of the population respectively.[54]

An ancient indigenous religion known as the Heraka is followed by 4,168 people belonging to the Zeliangrong tribe living in Nagaland.[61] Rani Gaidinliu was a freedom fighter who struggled for the revival of the traditional Naga religion. Today, 94% of the Kuki tribe people living in Nagaland are Christian.

Government

The governor is the constitutional head of state, representative of the President of India. He possesses largely ceremonial responsibilities apart from law and order responsibilities.

The Legislative Assembly of Nagaland (Vidhan Sabha) is the real executive and legislative body of the state. The 60-member Vidhan Sabha – all elected members of legislature – forms the government executive and is led by the Chief minister. Unlike most states in India, Nagaland has been granted a great degree of state autonomy, as well as special powers and autonomy for Naga tribes to conduct their own affairs. Each tribe has a hierarchy of councils at the village, range, and tribal levels dealing with local disputes.

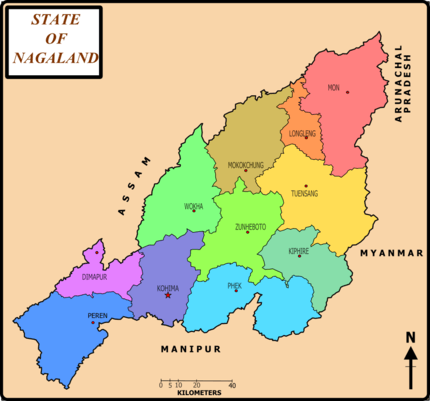

Districts

The following are districts

- Dimapur District – Dimapur-Chumukedima

- Kiphire District – Kiphire

- Kohima District – Greater Kohima

- Longleng District – Longleng

- Mokokchung District – Mokokchung

- Mon District – Mon

- Peren District – Peren

- Phek District – Phek

- Tuensang District – Tuensang

- Wokha District – Greater Wokha

- Zunheboto District – Zunheboto

Elections

The Democratic Alliance of Nagaland (DAN) is a state level coalition of political parties. It headed the government with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Janata Dal (United) (JDU). It was formed in 2003 after the Nagaland Legislative Assembly election, with the Naga People's Front (NPF), and the BJP.[62] The alliance has been in power in Nagaland since 2003.[63]

Urban centres

The major urban areas of Nagaland are Dimapur, Kohima, Mokokchung, Tuensang, Wokha, Mon, Zunheboto, Longleng and Kiphire, India . There are five urban agglomeration areas with population of more than 40,000 in the state:

| Rank | Metropolitan/Agglomeration Area | District | 2011 Census |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dimapur-Chumukedima | Dimapur District | 230,106 |

| 2 | Greater Kohima | Kohima District | 99,795 |

| 3 | Mokokchung Metropolitan Area | Mokokchung District | 60,161 |

| 4 | Greater Wokha | Wokha District | 43,089 |

| 5 | DC Hill Zunheboto | Zunheboto District | 40,138 |

Major towns that are non-district headquarters include Tuli town,Mangkolemba, Naganimora, Changtongya, Tizit, Tseminyu, Bhandari, Akuluto, Pfutsero, Aghunato , Aboi, Tobu.

Economy

The Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of Nagaland was about ₹12,065 crore (US$1.8 billion) in 2011-12.[64] Nagaland's GSDP grew at 9.9% compounded annually for a decade, thus more than doubling the per capita income.[8]

Nagaland has a high literacy rate of 80.1 per cent. Majority of the population in the state speaks English, which is the official language of the state. The state offers technical and medical education.[8] Nevertheless, agriculture and forestry contribute majority of Nagaland's Gross Domestic Product. The state is rich in mineral resources such as coal, limestone, iron, nickel, cobalt, chromium, and marble.[65] Nagaland has a recoverable reserve of limestone of 1,000 million tonnes plus a large untapped resource of marble and handicraft stone.

Most of state's population, about 68 per cent, depends on rural cultivation. The main crops are rice, millet, maize, and pulses. Cash crops, like sugarcane and potato, are also grown in some parts.

Plantation crops such as premium coffee, cardamom, and tea are grown in hilly areas in small quantities with a large growth potential. Most people cultivate rice as it is the main staple diet of the people. About 80% of the cropped area is dedicated to rice. Oilseeds is another, higher income crop gaining ground in Nagaland. The farm productivity for all crops is low, compared to other Indian states, suggesting significant opportunity for farmer income increase. Currently the Jhum to Terraced cultivation ratio is 4:3; where Jhum is local name for cut-and-burn shift farming. Jhum farming is ancient, causes a lot of pollution and soil damage, yet accounts for majority of farmed area. The state does not produce enough food, and depends on trade of food from other states of India.[2]

Forestry is also an important source of income. Cottage industries such as weaving, woodwork, and pottery are important sourcesof revenue.

Tourism has a lot of potential, but is largely limited due to insurgency and concern of violence over the last five decades. Nagaland's gross state domestic product for 2004 is estimated at $1.4 billion in current prices.

The state generates 87.98 MU compared to a demand for 242.88 MU. This deficit requires Nagaland to buy power. The state has significant hydroelectric potential, which if realised could make the state a power surplus state. In terms of power distribution, every village and town, and almost every household has an electricity connection; but, this infrastructure is not effective given the power shortage in the state.[2]

Tourism

Natural resources

After a gap of almost 20 years, Nagaland state Chief Minister, T. R. Zeliang launched the resumption of oil exploration in Changpang and Tsori areas, under Wokha district in July 2014. The exploration will be carried out by the Metropolitan Oil & Gas Pvt. Ltd. Zeliang has alleged failures and disputed payments made to the state made by previous explorer, the state owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC).[67]

Festivals

Nagaland is known in India as the land of festivals.[68] The diversity of people and tribes, each with their own culture and heritage, creates a year-long atmosphere of celebrations. In addition, the state celebrates all the Christian festivities. Traditional tribe-related festivals revolve round agriculture, as a vast majority of the population of Nagaland is directly dependent on agriculture. Some of the significant festivals for each major tribe are:[3]

| Tribe | Festival | Celebrated in |

|---|---|---|

| Angami | Sekrenyi | February |

| Ao | Moatsu, Tsungremong | May, August |

| Chakhesang | Tsukhenyie, Sekrenyi | April/May, January |

| Chang | Kundanglem, Nuknyu Lem | April, July |

| Dimasa Kachari | Bushu Jiba, | January, April |

| Khiamniungan | Miu Festival, Tsokum | May, October |

| Konyak | Aoleang Monyu,Lao-ong Mo | April,September |

| Kuki | Mimkut, Chavang kut | January, November |

| Lotha | Tokhu Emong | November |

| Phom | Monyu, Moha, Bongvum | April, May, October |

| Pochury | Yemshe | October |

| Rengma | Ngadah | September |

| Sangtam | Amongmong | September |

| Rongmei | Gaan-ngai | January |

| Sumi | Ahuna, Tuluni | November, July |

| Yimchungru | Metumniu, Tsungkamniu | August, January |

| Zeliang | Hega, Langsimyi/Chaga Gadi, and Mileinyi | February, October, March |

Hornbill Festival of Nagaland

Hornbill Festival[69] was launched by the Government of Nagaland in December 2000 to encourage intertribal interaction and to promote cultural heritage of the state. Organized by the State Tourism Department and Art & Culture Department. Hornbill Festival showcases a mélange of cultural displays under one roof. This festival takes place between 1 and 7 December every year.

It is held at Naga Heritage Village, Kisama which is about 12 km from Kohima. All the tribes of Nagaland take part in this festival. The aim of the festival is to revive and protect the rich culture of Nagaland and display its history, culture and traditions.[70]

The festival is named after the hornbill bird, which is displayed in folklores in most of the states tribes. The week-long festival unites Nagaland and people enjoy the colourful performances, crafts, sports, food fairs, games and ceremonies. Traditional arts which include paintings, wood carvings, and sculptures are on display. Festival highlights include traditional Naga Morungs rxhibition and sale of arts and crafts, food stalls, herbal medicine stalls, shows and sales, cultural medley – songs and dances, fashion shows, beauty contest, traditional archery, naga wrestling, indigenous games and musical concerts. Additional attractions include the Konyak fire eating demonstration, pork-fat eating competitions, the Hornbill Literature Festival (including the Hutton Lectures), Hornbill Global Film Fest, Hornbill Ball, Choral Panorama, North East India Drum Ensemble, Naga king chilli eating competition, Hornbill National Rock Contest,[71] Hornbill International Motor Rally and WW-II Vintage Car Rally.[72][73]

Transportation

The railway network in the state is minimal. Broad gauge lines run 7.98 miles (12.84 km), National Highway roads 227.0 miles (365.3 km), and state roads 680.1 miles (1,094.5 km). Road is the backbone of Nagaland's transportation network. The state has over 15,000 km of surfaced roads, but these are not satisfactorily maintained given the weather damage. In terms of population served for each kilometre of surfaced road, Nagaland is the second best state in the region after Arunachal Pradesh.[2]

Railway

Railway: North East Frontier Railway

- Broad gauge: 7.98 miles (12.84 km)

- Total: 7.98 miles (12.84 km)

[Data Source: N. F. Railway, CME Office, Guwahati-781011]

Roadway

National highways: 227.0 miles (365.3 km)

- NH 61: Kohima, Wokha, Tseminyu, Wokha, Mokokchung, Changtongya, Tuli

- NH 29: Dimapur-Kohima-Mao-Imphal (134.2 mi or 216.0 km)

- NH 36: Dimapur-Doboka-Nagaon (105.6 mi or 169.9 km)

- NH 150: Kohima-Jessami via Chakhabama-Pfutsero (74.6 mi or 120.1 km)

- NH 155: Mokukchung-Jessami via Tuesang-Kiphire (206.9 mi or 333.0 km)

State highways

There are 680.1 miles (1,094.5 km) of state highways:

- Chakabama–Mokokchung via Chazuba and Zunheboto

- Kohima–Meluri via Chakhabama

- Mokokchung–Mariani

- Mokokchung–Tuensang

- Namtola–Mon

- Tuensang–Mon–Naginimora

- Tuensang–Kiphire–Meluri

- Wokha–Merapani Road

Airway

- Dimapur airport, is 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from Dimapur, and 43.5 miles (70.0 km) from Kohima. It is the sole airport in Nagaland with scheduled commercial services to Kolkata, West Bengal and Dibrugarh, Assam. The airport's asphalt runway is 7513 feet long, at an elevation of 487 feet.[74]

Education

Nagaland schools are run by the state and central government or by private organisation. Instruction is mainly in English — the official language of Nagaland. Under the 10+2+3 plan, after passing the Higher Secondary Examination (the grade 12 examination), students may enroll in general or professional degree programs.

Nagaland has one Central University (Nagaland University), one engineering college (National Institute of Technology Nagaland) and one private university (a branch of the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of India).

Culture

The 16 main tribes of Nagaland are Angami, Ao, Chakhesang, Chang, Dimasa Kachari, Khiamniungan, Konyak, Lotha, Phom, Pochury, Rengma, Sangtam, Sumi, Yimchunger, Kuki and Zeliang. The Konyaks, Angamis, Aos, Lothas, and Sumis are the largest Naga tribes; there are several smaller tribes as well (see List of Naga tribes).

Tribe and clan traditions and loyalties play an important part in the life of Nagas. Weaving is a traditional art handed down through generations in Nagaland. Each of the tribe has unique designs and colours, producing shawls, shoulder bags, decorative spears, table mats, wood carvings, and bamboo works. Among many tribes the design of the shawl denotes the social status of the wearer. Some of the more known shawls include Tsungkotepsu and Rongsu of the Ao tribe; Sutam, Ethasu, Longpensu of the Lothas; Supong of the Sangtams, Rongkhim and Tsungrem Khim of the Yimchungers; the Angami Lohe shawls with thick embroidered animal motifs etc.

Folk songs and dances are essential ingredients of the traditional Naga culture. The oral tradition is kept alive through folk tales and songs. Naga folks songs are both romantic and historical, with songs narrating entire stories of famous ancestors and incidents. There are also seasonal songs which describe activities done in an agricultural season. Tribal dances of the Nagas give an insight into the inborn Naga reticence of the people. War dances and other dances belonging to distinctive Naga tribes are a major art form in Nagaland.

Newspapers

See also

- Outline of India

- Battle of the Tennis Court

- Foreigners (Protected Areas) Order 1958 (India)

- List of institutions of higher education in Nagaland

- Northeast Indian Railways during World War II

- Tourism in North East India

References

- ↑ Census of India 2011 Govt of India

- 1 2 3 4 5 Purusottam Nayak, Some Facts and Figures on Development Attainments in Nagaland, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper No. 51851, October 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Nagaland - State Human Development Report United Nations Development Programme (2005)

- ↑ Population by religious communities Census of India, 2001, Govt of India

- ↑ Gordon Pruett, Christianity, history, and culture in Nagaland, Indian Sociology, January 1974, vol. 8, no. 1, pp 51-65

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Charles Chasie (2005), Nagaland in Transition, India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 2/3, Where the Sun Rises When Shadows Fall: The North-east (MONSOON-WINTER 2005), pp. 253-264

- 1 2 3 Charles Chasie, Nagaland, Institute of Developing Economies (2008)

- 1 2 3 Nagaland Economy Report, 2011-2012 IBEF, India

- ↑ C.V. Prakash (2006), Encyclopedia of Northeast India, Vol. 5, Atlantic Publishers, ISBN 978-8126907076, pp. 2180-2181

- 1 2 Nagaland declared ‘Falcon capital of the World’ Assam Tribune (26 November 2013)

- ↑ Inato Yekheto Shikhu (2007). A re-discovery and re-building of Naga cultural values. Daya Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-89233-55-6.

- ↑ "Maps of India website - photograph of GH Damant grave headstone". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- 1 2 Gordon Pruett, Christianity, history, and culture in Nagaland, Indian Sociology January 1974 vol. 8 no. 1 51-65

- ↑ Tezenlo Thong, "‘Thy Kingdom Come': The Impact of Colonization and Proselytization on Religion among the Nagas," Journal of Asian and African Studies, no. 45, 6: 595–609

- ↑ Dougherty, Martin J. (2008). Land Warfare. Thunder Bay Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781592238293.

- ↑ Dennis, Peter; Lyman, Robert (2010). Kohima 1944: The Battle That Saved India. Osprey. p. ..

- ↑ A.M. Toshi Jamir, 'A Handbook of General Knowledge on Nagaland' (2013, 10th Edition) pg. 10

- 1 2 SK Sharma (2006), Naga Memorandum to the Simon Commission (1929), Mittal Publications, New Delhi India

- 1 2 "Naga Hills Tuensang Area Act, 1957".

- ↑ "The 16-point Agreement arrived at between the Government of India and the Naga People's Convention, July 1960". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Suresh K. Sharma (2006). Documents on North-East India: Nagaland. Mittal Publications. pp. 225–228. ISBN 9788183240956.

- ↑ "The State Of Nagaland Act, 1962". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Ovung, Albert. "The Birth of Ceasefire in Nagaland".

- ↑ Nagaland, Encyclopædia Britannica (2011)

- ↑ "All MLAs ready to sacrifice positions for Naga peace". 8 August 2012.

- ↑ Nagaland Violence Statistics, India Fatalities 1994-2014 SATP (2014)

- ↑ Global Burden of Armed Violence Chapter 2, Geneva Declaration, Switzerland (2011)

- ↑ Nagaland elections 2013 Elections Commission of India, Government of India

- ↑ Bert Sim, Mosstodloch, Aberdeenshire, Scotland: Pipe Major of the Gordon Highlanders at Kohima: his home is named "Kohima." – RJWilliams, Slingerlands, NY/USA

- ↑ Dougherty, Martin J. Land Warfare. Thunder Bay Press. p. 159.

- ↑ Dennis, Peter; Lyman, Robert (2010). Kohima 1944: The Battle That Saved India. Osprey.

- ↑ The World War II Cemetery in Kohima, Nagaland: A Moving Experience Kunzum, Ajay Jain (2010)

- ↑ Vibha Joshi, A Matter of Belief: Christian Conversion and Healing in North-East India, ISBN 978-0857455956, page 221

- ↑ Drouyer, A. Isabel, René Drouyer, THE NAGAS: MEMORIES OF HEADHUNTERS- Indo-Burmese Borderlands- Volume 1", White Lotus, 2016, p.168.

- ↑ C. R. Stonor (1950), The Feasts of Merit among the Northern Sangtam Tribe of Assam, Anthropos, Bd. 45, H. 1./3. (Jan. - Jun. 1950), pp. 1-12; Note: Nagaland was part of Assam in before 1963; this paper was published in 1950.

- ↑ Mills, J. P. (1935), The Effect of Ritual Upon Industries and Arts in the Naga Hills, Man, 132-135

- ↑ "Geography of Nagaland". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ "Climate of Nagaland". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Nagaland struggles to save state bird – The Telegraph Calcutta Monday, 5 July 2010

- ↑ "NRCM Nagaland". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ "Table 162, Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line". Reserve Bank of India, Government of India. 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ "Census Population" (PDF). Census of India. Ministry of Finance India. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ↑ Agarwal and Kumar, An Investigation into Changes in Nagaland's Population between 1971 and 2011 Paper 316, Institute of Economic Growth (2012)

- ↑ A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix

- ↑ "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Census Reference Tables, A-Series - Total Population". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ Census 2011 Non scheduled languages

- ↑ Bielenberg, B., & Nienu, Z. (2001). Chokri (Phek dialect): phonetics and phonology. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 24(2), 85-122

- 1 2 Braj Bihari Kumar (2005), Naga Identity, ISBN 978-8180691928, Chapter 6

- ↑ Matisoff, J. A. (1980). Stars, moon, and spirits: bright beings of the night in Sino-Tibetan, Gengo Kenkyu, 77(1), 45

- ↑ Khubchandani, L. M. (1997), Bilingual education for indigenous people in India. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education Volume 5, pp 67-76, Springer Netherlands

- ↑ "Population by religion community - 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ↑ Nagaland Population 2011 Census

- 1 2 "2011 Census".

- 1 2 Vibha Joshia, The Birth of Christian Enthusiasm among the Angami of Nagaland, Journal of South Asian Studies, Volume 30, Issue 3, 2007, pages 541-557

- ↑ Olson, C. Gordon. What in the World Is God Doing. Global Gospel Publishers: Cedar Knolls, NJ. 2003.

- ↑ Gillaspie, Gloria (5 April 2016). Arise! Shine!: For Your Light Is Come and the Glory of the Lord Is Risen Upon You. Charisma Media. p. 208. ISBN 9781629985046.

- ↑ Thong, Tezenlo (23 March 2016). Progress and Its Impact on the Nagas: A Clash of Worldviews. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 9781317075318.

- ↑ American Religious Identification Survey www.gc.cuny.edu. Archived 1 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mississippi Denominational Groups, 2000 Thearda.com. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Heraka". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ "DAN to stake claim in Nagaland". Rediff.com. 2 March 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Naga People's Front secures absolute majority in Assembly polls, set to form third consecutive government". India Today. PTI. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ State wise : Population, GSDP, Per Capita Income and Growth Rate Planning Commission, Govt of India; See third table 2011-2012 fiscal year, 19th row

- ↑ Anowar Hussain, Economy of North Eastern Region of India, Vol.1, Issue XII / June 2012, pp.1-4

- ↑ Chitta Ranjan Deb (2013), Orchids of Nagaland, propagation, conservation and sustainable utilization: a review, Pleione 7(1): 52 - 58

- ↑ Oil exploration resumes in Nagaland, (21 July 2014) Accessed from http://www.morungexpress.com/frontpage/119064.html on 18 October 2014

- ↑ Nagaland Government of Nagaland (2009)

- ↑ "Hornbill Festival official website". Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Hornbill Festival www.festivalsofindia.in

- ↑ Hornbill National Rock Contest official website

- ↑ 2 crore 7-day Hornbill Festival to enthrall nagalandpost.com Retrieved 3 December 2011

- ↑ Hornbill International Motor Rally starts nagalandpost.com Retrieved 3 December 2011

- ↑ Dimapur airport World Aero Data (2012)

Further reading

- Drouyer, A. Isabel, René Drouyer, "THE NAGAS: MEMORIES OF HEADHUNTERS- Indo-Burmese Borderlands-vol. 1", White lotus, 2016, ISBN 978-2-9545112-2-1.

- Alban von Stockhausen. 2014. Imag(in)ing the Nagas: The Pictorial Ethnography of Hans-Eberhard Kauffmann and Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf. Arnoldsche, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-89790-412-5.

- Stirn, Aglaja & Peter van Ham. The Hidden world of the Naga: Living Traditions in Northeast India. London: Prestel.

- Oppitz, Michael, Thomas Kaiser, Alban von Stockhausen & Marion Wettstein. 2008. Naga Identities: Changing Local Cultures in the Northeast of India. Gent: Snoeck Publishers.

- Kunz, Richard & Vibha Joshi. 2008. Naga – A Forgotten Mountain Region Rediscovered. Basel: Merian.

- Glancey, Jonathan. 2011. Nagaland: a Journey to India's Forgotten Frontier. London: Faber

- Hattaway, Paul. 2006. 'From Head Hunters To Church Planters'. Authentic Publishing

- Hutton, J. 1986. 'Report on Naga Hills' Delhi: Mittal Publication.

External links

- Official website

- State Portal of the Government of Nagaland

-

Nagaland travel guide from Wikivoyage

Nagaland travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nagaland. |

|

Arunachal Pradesh |  | ||

| Assam | |

| ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Manipur |