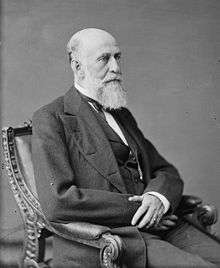

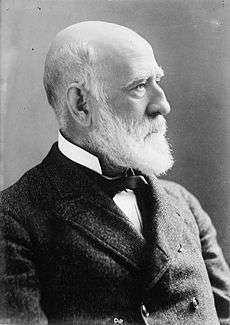

George F. Edmunds

| George F. Edmunds | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Vermont | |

|

In office April 3, 1866 – November 1, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Solomon Foot |

| Succeeded by | Redfield Proctor |

| Member of the Vermont Senate | |

|

In office 1861–1862 | |

| Member of the Vermont House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1854–1860 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

George Franklin Edmunds February 1, 1828 Richmond, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died |

February 27, 1919 (aged 91) Pasadena, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Susan Marsh Edmunds |

| Profession | Lawyer |

George Franklin Edmunds (February 1, 1828 – February 27, 1919) was a Republican U.S. Senator from Vermont. Before entering the U.S. Senate, he served in a number of high profile positions, including Speaker of the Vermont House of Representatives, and President pro tempore of the Vermont State Senate.

Edmunds was born in Richmond, Vermont and began to study law while still a teenager; he proved an adept student, and was admitted to the bar as soon as he reached the minimum required age of 21. He practiced in Burlington and became active in local politics and government.

After terms in the Vermont House of Representatives and Vermont State Senate, Edmunds was appointed to the U.S. Senate in 1866, filling the vacancy caused by the death of Solomon Foot. He was subsequently elected by the Vermont General Assembly, and reelected in 1868, 1874, 1880, and 1886. Edmunds served from April 1866 until resigning in November 1991. As a longtime member of the U.S. Senate, he served in a variety of leadership posts, including chairman of the Committee on Pensions, the Committee on the Judiciary, the Committee on Private Land Claims, and the Committee on Foreign Relations. He was also the leader of the Senate's Republicans in his roles as President pro tempore of the Senate and chairman of the Republican Conference.

Edmunds was an unsuccessful candidate for president at the 1880 and 1884 Republican National Conventions.

After leaving the Senate he practiced law in Philadelphia. He later lived in retirement in Pasadena, California, where he died in 1919. He was buried at Green Mount Cemetery in Burlington, Vermont.

Early life

George F. Edmunds was born in Richmond, Vermont on February 1, 1828. He attended the local schools and was privately tutored. Edmunds began studying law as a teenager, spending time in both the office of his brother in law and the office of David A. Smalley and Edward J. Phelps. He was admitted to the bar as soon as he was eligible in 1849. He practiced in Burlington, and became active in politics by serving in local offices including Town Meeting Moderator.[1][2][3][4]

While practicing law, one of the students who studied under him was Russell S. Taft, who later served as Lieutenant Governor and as Chief Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court.[5]

A Republican, he was elected to the Vermont House of Representatives in 1854. He served until 1860, and was Speaker from 1857 to 1860. He moved to the Vermont State Senate in 1861, where he served until 1862. While in the State Senate, Edmunds was chosen to serve as President pro tempore.[6][7]

United States Senate

After the death of U.S. Senator Solomon Foot in March 1866, Governor Paul Dillingham was expected to appoint someone from the west side of the Green Mountains, in keeping with the Republican Party's Mountain Rule. He first considered former Governor J. Gregory Smith. When Smith indicated that he would not accept, Dillingham turned to Edmunds, who had favorably impressed Dilingham during their service together in the State Senate, and whose residence in Burlington was on the west side of the state. Edmunds subsequently won reelection in 1868, 1874, 1880 and 1886, and served from April 1866 until resigning in November 1891.[8]

In the Senate, Edmunds took an active part in the attempt to impeach President Andrew Johnson in 1868.[9]

He was influential in providing for the electoral commission to decide the disputed presidential election of 1876 and served as one of the commissioners, voting for Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and William A. Wheeler.[10]

He was the author of the Edmunds Act against polygamy in Utah and the Sherman Antitrust Act to limit monopolies.[11][12]

In 1882 President Chester A. Arthur nominated Senator Roscoe Conkling to replace the retiring Ward Hunt as a Justice of the United States Supreme Court. When Conkling declined, Arthur chose Edmunds, who also declined. The appointment ultimately went to Samuel Blatchford.[13]

Senate leadership positions

Edmunds served as chairman of the Committee on Pensions from 1869 to 1873, the Committee on the Judiciary from 1872 to 1879 and again from 1881 to 1891, the Committee on Private Land Claims from 1879 to 1881 and the Committee on Foreign Relations in 1881. He was President pro tempore of the Senate from 1883 to 1885 and chairman of the Republican Conference from 1885 to 1891.

Reputation in the Senate

While serving in Congress he continued to practice law, as did many other members of Congress at the time. He held retainers from railroads and other corporations, including those which could be affected by Senate action.[14][15]

An acerbic debater, he often favored the status quo or slow progress. He was known for making his colleagues feel the sting of his criticisms, and some thought him better at merely opposing than offering constructive alternatives. David Davis joked that he could make Edmunds vote against any measure by simply phrasing the request for votes in the New England town meeting way: "Contrary-minded will say no."[16] One friend trying to interest him in a presidential bid pleaded, "But, Edmunds, think how much fun you would have vetoing bills."[17]

Edmunds took special delight in goading southern senators into blurting out statements that would embarrass the Democratic Party. To those southerners opposed to any federal role in protecting blacks' right to vote, Edmunds seemed the epitome of Yankee evil. One southern correspondent in 1880 wrote, "When I look at that man sitting almost alone in the Senate, isolated in his gloom of hate and bitterness, stern, silent, watchful, suspicious and pitiless, I am reminded of the worst types of Puritan character... You see the impress of the purer persecuting spirit that burned witches, drove out Roger Williams, hounded Jonathan Edwards for doing his sacred duty, maligned Jefferson, and like a toad squatted at the ear of the Constitution it had failed to pervert."[18]

But Edmunds also had admirers. One Democrat with no reason to appreciate him wrote a colleague that among all the Republicans, "Edmunds made the most impression upon me. I couldn't help admiring his clear and incisive way of putting a question, although it appeared to me that his manner is occasionally very irritating. This manner of his is very much that of a lawyer employed as counsel in a case, who therefore makes ex parte statements, and thinks it fair to make all manner of allegations."[19] His closest friend in the chamber for many years was the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, Senator Allen G. Thurman of Ohio.[20]

Presidential candidacies

Edmunds was a candidate for President at the 1880 Republican National Convention. Nominated by Frederick H. Billings, he received 34 votes on the first ballot. His support remained at 31 or 32 votes through the 29th ballot, after which his supporters began to trend towards eventual nominee James A. Garfield.[21][22]

In 1884, Republicans who favored civil service reform, including Theodore Roosevelt, supported Edmunds for President over incumbent President Chester Alan Arthur and former Senator James G. Blaine, hoping to build a groundswell for Edmunds if the two stronger candidates deadlocked. Revelations about Edmunds' legal work for railroads and corporations while sitting in the Senate prevented Edmunds from attaining wide support from reformers. On the first ballot he received 93 votes, but his support declined, and the nomination went to Blaine on the fourth ballot. Edmunds was among the Republicans who gave lukewarm support to Blaine (some backed Cleveland outright), and Blaine lost the general election to Grover Cleveland. At Arthur's funeral in 1886, Edmunds extended his hand to Blaine. Blaine, recalling the 1884 campaign, refused to shake it.[23][24][25]

Senate resignation, retirement and death

Edmunds resigned from the Senate in 1891 in order to start a law practice in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[26]

He later retired to Pasadena, California where he died on February 27, 1919.[27] He was buried at Green Mount Cemetery in Burlington.[28]

Family

In 1852 Edmunds married Susan Marsh Lyman (1831-1916), a niece of George Perkins Marsh.[29][30] They had two daughters, Mary (1854-1936) and Julia (1861-1882).[31][32]

Awards

Among Edmunds's honors were an honorary master of arts from the University of Vermont and honorary LL.D. degrees from Middlebury College, Dartmouth College and the University of Vermont.[33][34]

Legacy

Edmunds Elementary and Middle Schools in Burlington, which share a complex, opened as the city's high school in 1900 on land donated by Edmunds, and became a middle and elementary grades facility in 1964.[35][36]

Mount Rainier's Edmunds Glacier[37] and the town of Edmonds, Washington (despite the spelling) are named for him.[38]

The Vermont Historical Society maintains the George F. Edmunds Fund, which awards an annual prize for student research and writing on Vermont history.[39]

His birthplace in Richmond, Vermont is a privately owned residence and farm, and marked by a Vermont Historic Sites Commission sign.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ Henry Wilson Scott, Distinguished American Lawyers, 1891, page 333

- ↑ Walter Hill Crockett, George Franklin Edmunds, 1919, page 1855

- ↑ Hiram Carleton, Genealogical and Family History of the State of Vermont, Vilume 1, page 711

- ↑ Jacob G. Ullery, Men of Vermont Illustrated, 1894, page 118

- ↑ The Vermonter magazine, Obituary: Russell Smith Taft, April 1902, page 160

- ↑ Vermont Secretary of State, Vermont Legislative Directory, 1969, page 320

- ↑ Marcus Davis Gilman, The Bibliography of Vermont, 1897, page 81

- ↑ John J. Duffy, Samuel B. Hand, Ralph H. Orth, editors, The Vermont Encyclopedia, 2003, page 113

- ↑ John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, 1995, Chapter 31

- ↑ Elbert William Robinson Ewing, History and Law of the Hayes-Tilden Contest Before the Electoral Commission: The Florida Case, 1877, page 40

- ↑ Trade and Transportation: A Monthly Journal of American Trade, Senator Edmunds on the Anti-Trust Law, December 1911, page 334

- ↑ Paul Finkelman, editor, Religion and American Law: An Encyclopedia, 1999, page 318

- ↑ Jost, Kenneth (1998). The Supreme Court A-Z. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-5795-8124-4.

- ↑ Vermont General Assembly, Report of the Joint Special Committee to Investigate the Vt. Central Railroad, 1873, page 374

- ↑ Edward Chase Kirkland, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., 1835-1915: The Patrician at Bay, 1965, page 109

- ↑ George F. Hoar, Scribner's magazine, Four National Conventions, February 1899, page 159

- ↑ George F. Hoar, "Autobiography of Seventy Years" (New York: Scribner's Sons, 1903), 1:388.

- ↑ Selig Alder, "The Senatorial Career of George Franklin Edmunds, 1866-1891," Ph. D. dissertation, University of Illinois, 1934, p. 202.

- ↑ Perry Belmont to Thomas F. Bayard, January 11, 1875, Thomas F. Bayard Papers, Library of Congress.

- ↑ George Harold Walker, The Chautauquan, Moral and Social Reforms in Congress, October 1891 to March 1892, page 314

- ↑ The University Magazine, University Biographies: The Hon. Frederick Billings, LL.D., November 1891, page 1077

- ↑ Republican National Committee, History of the Republican Party Together with the Proceedings of the Republican National Convention, 1896, page 48

- ↑ Republican National Committee, Official Proceedings of the Republican National Convention, 1884, pages 141, 162

- ↑ America: A Journal for Americans, From Washington, February 4, 1889, page 11

- ↑ William Roscoe Thayer, Theodore Roosevelt: An Intimate Biography, 1919, page 49

- ↑ Review of Reviews and World's Work, Ex-Senator George F. Edmunds, Author of the Anti-Trust Law, January 1912, page 2

- ↑ New York Times, George F. Edmunds Dead at 91 Years, February 27, 1919

- ↑ George F. Edmunds at Find a Grave

- ↑ Susan Marsh Edmunds at Find a Grave

- ↑ John J. Duffy, Samuel B. Hand, Ralph H. Orth, editors, The Vermont Encyclopedia, 2003, page 113

- ↑ Mary Mayhew Edmunds at Find a Grave

- ↑ Julia M. Edmunds at Find a Grave

- ↑ Middlebury College, Catalogue of the Officers and Alumni of Middlebury College, 1890, page 168

- ↑ University of Vermont, General Catalogue, 1901, page 225

- ↑ Vermont Secretary of State, Legislative Directory, 1969, pages 593, 684

- ↑ Charles Edwin Allen, About Burlington Vermont, 1905, page 62

- ↑ Majors, Harry M. (1975). Exploring Washington. Van Winkle Publishing Co. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-918664-00-6.

- ↑ Historic Edmonds, The Founding and Beginning of Edmonds, Washington, 1876-1906, 2000, page 47

- ↑ Vermont Historical Society, Special prizes, retrieved March 11, 2014

- ↑ Historic Sites, State of Vermont, Roadside Historic Markers List, retrieved March 11, 2014

External links

- United States Congress. "George F. Edmunds (id: E000056)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George W. Grandey |

Speaker of the Vermont House of Representatives 1857–1860 |

Succeeded by Augustus P. Hunton |

| Preceded by Frederick E. Woodbridge |

President pro tempore of the Vermont State Senate 1861–1862 |

Succeeded by Henry E. Stoughton |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Solomon Foot |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Vermont April 3, 1866 – November 1, 1891 Served alongside: Luke P. Poland and Justin S. Morrill |

Succeeded by Redfield Proctor |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by David Davis |

President pro tempore of the United States Senate March 4, 1883 – March 3, 1885 |

Succeeded by John Sherman |

| Preceded by John Sherman |

Chairman of the Republican Conference of the United States Senate 1885 – 1891 | |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by William Sprague |

Most Senior Living U.S. Senator (Sitting or Former) September 11, 1915 – February 27, 1919 |

Succeeded by Cornelius Cole |