Mari, Syria

| تل حريري (Arabic) | |

Ziggurat at Mari | |

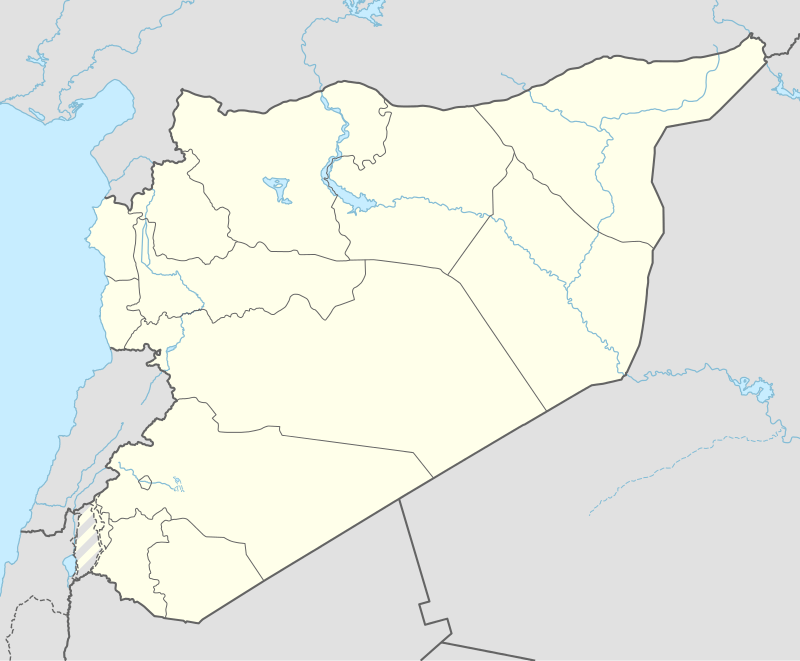

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternate name | Tell Hariri |

|---|---|

| Location | Abu Kamal, Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 34°32′58″N 40°53′24″E / 34.54944°N 40.89000°ECoordinates: 34°32′58″N 40°53′24″E / 34.54944°N 40.89000°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 60 hectares (150 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 2900 BC |

| Abandoned | 3rd century BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | East-Semitic (Kish civilization), Amorite |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | André Parrot |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

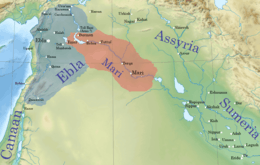

Mari (modern Tell Hariri), was an ancient Semitic city in Syria. Its remains constitute a tell located 11 kilometers north-west of Abu Kamal on the Euphrates river western bank, some 120 kilometers southeast of Deir ez-Zor. It flourished as a trade center and hegemonic state between 2900 BC and 1759 BC.[note 1] As a purposely built city, the existence of Mari was related to its position in the middle of the Euphrates trade routes; this position made it an intermediary between Sumer in the south and the Levant in the west.

Mari was first abandoned in the middle of the 26th century BC but was rebuilt and became the capital of a hegemonic East-Semitic state before 2500 BC. This second Mari engaged in a long war with its rival Ebla, and is known for its strong affinity with the Sumerian culture. It was destroyed in the 23rd century BC by the Akkadians who allowed the city to be rebuilt and appointed a military governor bearing the title of Shakkanakku (military governor). The governors later became independent with the rapid disintegration of the Akkadian empire and rebuilt the city as a regional center in the middle Euphrates valley. The Shakkanakkus ruled Mari until the second half of the 19th century BC when the dynasty collapsed for unknown reasons. A short time after the Shakkanakku collapse, Mari became the capital of the Amorite Lim dynasty. The Amorite Mari was short lived as it was annexed by Babylonia in c. 1761 BC, but the city survived as a small settlement under the rule of the Babylonians and the Assyrians before being abandoned and forgotten during the Hellenistic period.

The Mariotes worshiped both Semitic and Sumerian deities and established their city as a center of old trade. However, although the pre-Amorite periods were characterized by heavy Sumerian cultural influence, Mari was not a city of Sumerian immigrants but rather a Semitic speaking nation that used a dialect similar to Eblaite. The Amorites were West-Semites who began to settle the area before the 21st century BC; by the Lim dynasty's era (c. 1830 BC), they became the dominant population in the Fertile Crescent.

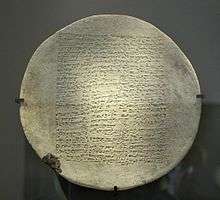

Mari's discovery in 1933 provided an important insight into the geopolitical map of ancient Mesopotamia and Syria, due to the discovery of more than 25,000 tablets that contained important information about the administration of state during the second millennium BC and the nature of diplomatic relations between the political entities in the region. They also revealed the wide trading networks of the 18th century BC, which connected areas as far as Afghanistan in Southern Asia and Crete in the Mediterranean region.

History

The name of the city can be traced to Mer, an ancient storm deity of northern Mesopotamia and Syria who was considered the patron deity of the city,[1] Georges Dossin noted that the name of the city was spelled identically like the name of the storm god and concluded that Mari was named after him.[2]

The first kingdom

Mari is not considered a small settlement that later grew,[3] but rather a new city that was purposely founded during the Mesopotamian Early Dynastic period I c. 2900 BC, to control the waterways of the Euphrates trade routes that connect the Levant with the Sumerian south. [3][4] The city was built about 1 to 2 kilometers away from the Euphrates river to protect it from floods,[3] and was connected to the river by an artificial canal that was between 7 and 10 kilometers long depending on which old meander it used to be attached with, which is hard to identify today.[5]

The city is difficult to excavate, as it is buried deep under the later layers of habitation.[4] A defensive system against floods, composed of a circular embankment was unearthed,[4] in addition to a circular 6.7 m thick internal rampart to protect the city from enemies.[4] An area of 300 meters long filled with gardens and craftsmen quarters,[5] separated the outer embankment from the inner rampart which had a height of 8 to 10 meters, and was strengthened by defensive towers.[5] Other findings include one of the city gates, a street beginning at the center and ending at the gate, in addition to residential houses.[4] Mari had a central mound,[6] however no temple or palaces have been unearthed,[4] although a large building that seems to have been an administrative one was unearthed which had stone foundations and dimensions of (32 meters X 25 meters), with rooms up to 12 meters long and 6 meters wide.[7] The city was abandoned at the end of the Early Dynastic period II c. 2550 BC for unknown reasons.[4]

The second kingdom

| Second Mariote Kingdom | ||||||||

| Mari | ||||||||

| ||||||||

The second kingdom during the reign of Iblul-Il | ||||||||

| Capital | Mari | |||||||

| Languages | Mariote dialect | |||||||

| Religion | Mesopotamian | |||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | |||||||

| • | Established | c. 2500 BC | ||||||

| • | Disestablished | c. 2290 BC | ||||||

| ||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||

Around the beginning of the Early Dynastic period III (earlier than 2500 BC),[8] Mari was rebuilt and populated again.[4][9] The new city kept many of the first city exterior features, including the internal rampart and gate.[4][10] Also kept was the outer circular embankment measuring 1.9 km in diameter, which was topped by a wall that is two meters thick,[10] which is suitable for the protection of archers.[4]

However, the internal structure was completely changed,[11] the city was carefully planned; first to be built were the streets that descends from the elevated center into the gates, ensuring the drainage of rain water.[4]

At the heart of the city, a royal palace was built which also served as a temple.[4] Four successive architectural levels from the second kingdom's palace have been unearthed (the oldest is designated P3, while the latest is P0), and the last two levels are dated to the Akkadian period.[12] The first two levels were excavated;[12] the findings include a temple named Enceinte Sacrée,[note 2] which was the largest in the city but it is unknown for whom it was dedicated.[12][13] Also unearthed were a pillared throne room and a hall that have three double wood pillars leading to the temple.[12]

Six more temples were discovered in the city, including the temple called the Massif Rouge (to whom it was dedicated is unknown), and temples dedicated for Ninni-Zaza, Ishtarat,[14] Ishtar, Ninhursag and Shamash.[13] All the temples were located in the center of the city except for the Ishtar temple and the area between the Enceinte Sacrée and the Massif Rouge is considered the administrative center of the high priest.[13]

The second kingdom appears to be a powerful and prosperous political center,[8] kings held the title of Lugal,[15] and many are attested in the city, but the most important source is the letter of king Enna-Dagan c. 2350 BC,[note 3][17] which was sent to Irkab-Damu of Ebla,[note 4] and in it, the Mariote king mentions his predecessors and their military achievements.[19] However, the reading of this letter is still problematic and many interpretations have been presented by scholars.[20][21][22]

Mari-Ebla war

The earliest attested king in the letter of Enna-Dagan is Ansud, who is mentioned as attacking Ebla, the traditional rival of Mari with whom it had a long war,[23] and conquering many of Ebla's cities, including the land of Belan.[note 5][22] The next king mentioned in the letter is Saʿumu, who conquered the lands of Ra'ak and Nirum,[note 6][22] but king Kun-Damu of Ebla defeated Mari in the middle of the 25th century BC.[26] The war continued with Išhtup-Išar of Mari conquest of Emar,[22] at a time of Eblaite weakness in the mid-24th century BC. King Igrish-Halam of Ebla had to pay tribute to Iblul-Il of Mari,[26][27] who is mentioned in the letter conquering many of Ebla's cities and campaigning in the Burman region.[22]

Enna-Dagan also received tribute,[27] and his reign fell entirely within the reign of Irkab-Damu of Ebla,[28] who managed to defeat Mari and end the tribute.[18] Mari defeated Ebla's ally Nagar in year seven of the Eblaite vizier Ibrium's term, causing the blockage of trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia.[29] The war reached a climax when the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish made an alliance with Nagar and Kish to defeat Mari in a battle near Terqa.[30] Ebla itself suffered its first destruction a few years after Terqa in c. 2300 BC,[31] during the reign of the Mariote king Hidar.[32]

According to Alfonso Archi, Hidar was succeeded by Isqi-Mari whose royal seal was discovered and it depicts battle scenes, causing Archi to suggest that he was responsible for the destruction of Ebla while still a general.[32][33] Just a decade after Ebla's destruction (c. 2300 BC middle chronology),[34] Mari itself was destroyed and burned by Sargon of Akkad,[35] Michael Astour give the date as c. 2265 BC (short chronology).[36]

The third kingdom

| Third Mariote Kingdom | ||||||||||

| Mari | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

The third kingdom during the reign of Zimri-Lim c. 1764 BC | ||||||||||

| Capital | Mari | |||||||||

| Languages | Akkadian, Amorite | |||||||||

| Religion | Levantine Religion | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | |||||||||

| • | Established | c. 2266 BC | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | c. 1761 BC | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

Mari was deserted for two generations before being restored by the Akkadian king Manishtushu.[37][38] A governor was appointed to govern the city who held the title "Shakkanakku" (military governor).[38] Akkad kept direct control over the city, which is evident by Naram-Sin of Akkad's appointment of two of his daughters to priestly offices in the city.[38]

The Shakkanakku dynasty

The first member of the Shakkanakku dynasty on the lists is Ididish who was appointed in c. 2266 BC,[note 7][40] according to the lists, Ididish ruled for 60 years,[41] and was succeeded by his son making the position hereditary.[42]

The third Mari followed the second city in terms of general structure,[43] phase P0 of the old royal palace was replaced by a new palace for the Shakkanakku.[44] Another smaller palace was built in the eastern part of the city,[6] and contained royal burials that date to the former periods.[45] The ramparts were rebuilt and strengthened while the embankment was turned into a defensive wall that reached 10 meters in width.[44] The former sacred inclosure was maintained,[44] so was the temple of Ninhursag. However, the temples of Ninni-Zaza and Ishtarat disappeared,[44] while a new temple called the "temple of lions" (dedicated to Dagan),[46] was built by the Shakkanakku Ishtup-Ilum and attached to it, was a rectangular terrace (ziggurat) that measured 40 x 20 meters for sacrifices.[44][6][47]

Akkad disintegrated following Shar-Kali-Sharri's reign,[48] and Mari gained its independence, but the use of the Shakkanakku title continued during the following Third Dynasty of Ur period.[49] A princess of Mari married the son of king Ur-Nammu of Ur,[50][51] and Mari was nominally under Ur hegemony.[52] However, the vassalage did not impede the independence of Mari,[53][54] and some Shakkanakkus used the royal title Lugal in their votive inscriptions, while using the title of Shakkanakku in their correspondence with the Ur's court.[55] The dynasty ended for unknown reasons not long before the establishment of the next dynasty, which took place in the second half of the 19th century BC.[56][57][58]

The Lim dynasty

The second millennium BC in the Fertile Crescent was characterized by the expansion of the Amorites, which culminated with them dominating and ruling most of the region,[59] including Mari which in c. 1830 BC, became the seat of the Amorite Lim dynasty under king Yaggid-Lim.[58][60] However, the epigraphical and archaeological evidences showed a high degree of continuity between the Shakkanakku and the Amorite eras.[note 8][50]

Yaggid-Lim was the ruler of Suprum before establishing himself in Mari,[note 9][note 10][63] he entered an alliance with Ila-kabkabu of Ekallatum, but the relations between the two monarchs changed to an open war.[62][64] The conflict ended with Ila-kabkabu capturing Yaggid-Lim's heir Yahdun-Lim and according to a tablet found in Mari, Yaggid-Lim who survived Ila-kabkabu was killed by his servants.[note 11][62] However, in c. 1820 BC Yahdun-Lim was firmly in control as king of Mari.[note 12][64]

.jpg)

Yahdun-Lim started his reign by subduing seven of his rebelling tribal leaders, and rebuilding the walls of Mari and Terqa in addition to building a new fort which he named Dur-Yahdun-Lim.[66] He then expanded west and claimed to have reached the Mediterranean,[67][68] however he later had to face a rebellion by the Banu-Yamina nomads who were centered at Tuttul, and the rebels were supported by Yamhad's king Sumu-Epuh, whose interests were threatened by the recently established alliance between Yahdun-Lim and Eshnunna.[53][67] Yahdun-Lim defeated the Yamina but an open war with Yamhad was avoided,[69] as the Mariote king became occupied by his rivalry with Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria, the son of the late Ila-kabkabu.[70] The war ended in a defeat for Mari,[70][71] and Yahdun-Lim was assassinated in c. 1798 BC by his possible son Sumu-Yamam,[72][73] who himself got assassinated two years after ascending the throne while Shamshi-Adad advanced and annexed Mari.[74]

The Assyrian era and the Lim restoration

Shamshi-Adad appointed his son Yasmah-Adad on the throne of Mari, the new king married Yahdun-Lim's daughter,[75][76] while the rest of the Lim family took refuge in Yamhad,[77] and the annexation was officially justified by what Shamshi-Adad considered sinful acts on the side of the Lim family.[78] To strengthen his position against his new enemy Yamhad, Shamshi-Adad married Yasmah-Adad to Betlum, the daughter of Ishi-Adad of Qatna.[76] However, Yasmah-Adad neglected his bride causing a crisis with Qatna, and he proved to be an unable leader causing the rage of his father who died in c. 1776 BC,[76][79][80] while the armies of Yarim-Lim I of Yamhad were advancing in support of Zimri-Lim, the heir of the Lim dynasty.[note 13][80]

As Zimri-Lim advanced, a leader of the Banu-Simaal (Zimri-Lim's tribe) overthrew Yasmah-Adad,[82] opening the road for Zimri-Lim who arrived a few months after Yasmah-Adad's escape,[83] and married princess Shibtu the daughter of Yarim-Lim I a short time after his enthronement in c. 1776 BC.[80] Zimri-Lim's ascension to the throne with the help of Yarim-Lim I affected Mari's status, Zimri-Lim referred to Yarim-Lim as his father, and the Yamhadite king was able to order Mari as the mediator between Yamhad's main deity Hadad and Zimri-Lim, who declared himself a servant of Hadad.[84]

Zimri-Lim started his reign with a campaign against the Banu-Yamina, he also established alliances with Eshnunna and Hammurabi of Babylon,[77] and sent his armies to aid the Babylonians.[85] The new king directed his expansion policy toward the north in the Upper Khabur region, which was named Izdamaraz,[86] where he subjugated the local petty kingdoms in the region such as Urkesh,[87] and Talhayum, forcing them into vassalage.[88] The expansion was met by the resistance of Qarni-Lim, the king of Andarig,[89] whom Zimri-Lim defeated, securing the Mariote control over the region in c. 1771 BC,[90] and the kingdom prospered as a trading center and entered a period of relative peace.[80] Zimri-Lim's greatest heritage was the renovation of the Royal Palace, which was expanded greatly to contain 275 rooms,[6][91] exquisite artifacts such as The Goddess of the Vase statue,[92] and a royal archive that contained 25000 tablets.[93]

Mari's alliance with Eshnunna contributed to its demise, as that city later became an enemy of Hammurabi.[94] The relations with Babylon worsened with a dispute over the city of Hīt that consumed much time in negotiations,[95] during which a war against Elam involved both kingdoms in c. 1765 BC.[96] Finally, the kingdom was invaded by Hammurabi who defeated Zimri-Lim in battle in c. 1761 BC and ended the Lim dynasty,[97][98] while Terqa became the capital of a rump state named the Kingdom of Hana.[99]

Later periods

Mari survived the destruction and rebelled against Babylon in c. 1759 BC, causing Hammurabi to destroy the whole city.[100] However, Mari was allowed to survive as a small village under Babylonian administration, an act that Hammurabi considered merciful.[100] Later, Mari became part of Assyria and was listed among the territories conquered by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (reigned 1243–1207 BC).[101] Afterward, Mari constantly changed hands between Assyria and Babylon.[101]

In the middle of the eleventh century BC, Mari became part of Hana whose king Tukulti-Mer took the title king of Mari and rebelled against Assyria, causing the Assyrian king Ashur-bel-kala to attack the city.[101] Mari came firmly under the authority of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was assigned in the first half of the 8th century BC to a certain Nergal-Erish to govern under the authority of king Adad-Nirari III (reigned 810-783 BC).[101] In c. 760 BC, Shamash-Risha-Usur,[102] an autonomous governor ruling parts of the upper middle Euphrates under the nominal authority of Ashur-dan III, styled himself the governor of the lands of Suhu and Mari, so did his son Ninurta-Kudurri-Usur.[101] However, by that time, Mari was known to be located in the so-called Land of Laqe,[note 14] making it unlikely that the Usur family actually controlled it, and suggesting that the title was employed out of historical reasons.[101] The city continued as a small settlement until the Hellenistic period before disappearing from records.[101]

People, language and government

The founders of the first city may have been Sumerians or more probably East Semitic speaking people from Terqa in the north.[3] I. J. Gelb relates Mari's foundation with the Kish civilization,[104] which was a cultural entity of East Semitic speaking populations, that stretched from the center of Mesopotamia to Ebla in the western Levant.[105]

At its height, the second city was the home of about 40,000 people.[106] This population was East-Semitic speaking one, and used a dialect much similar to the language of Ebla (the Eblaite language),[9][107] while the Shakkanakku period had an East-Semitic Akkadian speaking population.[108] West Semitic names started to be attested in Mari since the second kingdom era,[109] and by the middle Bronze-Age, the west Semitic Amorite tribes became the majority of the pastoral groups in the middle Euphrates and Khabur valleys.[110] Amorite names started to be observed in the city toward the end of the Shakkanakku period, even among the ruling dynasty members.[111]

During the Lim era, the population became predominantly Amorite but also included Akkadian named people,[note 15] and although the Amorite language became the dominant tongue, Akkadian remained the language of writing.[112][113][114] The pastoral Amorites in Mari were called the Haneans, a term that indicate nomads in general,[115] those Haneans were split into the Banu-Yamina (sons of the right) and Banu-Simaal (sons of the left), with the ruling house belonging to the Banu-Simaal branch.[115] The kingdom was also a home to tribes of Suteans who lived in the district of Terqa.[116]

Mari was an absolute monarchy, with the king controlling every aspect of the administration, helped by the scribes who played the role of administrators.[117][118] During the Lim era, Mari was divided into four provinces in addition to the capital, the provincial seats were located at Terqa, Saggaratum, Qattunan and Tuttul. Each province had its own bureaucracy,[118] the government supplied the villagers with ploughs and agricultural equipments, in return for a share in the harvest.[119]

Kings of Mari

The Sumerian King List (SKL) records a dynasty of six kings from Mari enjoying hegemony between the dynasty of Adab and the dynasty of Kish.[120] The names of the Mariote kings were damaged on the early copies of the list,[23] and those kings were correlated with historical kings that belonged to the second city.[9] However, an undamaged copy of the list that date to the old Babylonian period was discovered in Shubat-Enlil,[23] and the names bears no resemblance to any of the historically attested monarchs of the second city,[23] indicating that the compilers of the list had an older and probably a legendary dynasty in mind, that predate the second city.[23]

The chronological order of the kings from the second kingdom era is highly uncertain; nevertheless, it is assumed that the letter of Enna-Dagan lists them in a chronological order.[121] Many of the kings were attested through their own votive objects discovered in the city,[122][123] and the dates are highly speculative.[123]

For the Shakkanakkus, the lists are incomplete and after Hanun-Dagan who ruled at the end of the Ur era c. 2008 BC (c. 1920 BC Short chronology), they become full of lacunae.[124] Roughly 13 more Shakkanakkus succeeded Hanun-Dagan but only few are known, with the last known one reigning not too long before the reign of Yaggid-Lim who founded the Lim dynasty in c. 1830 BC.[57][125]

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_28-5-2006.jpg)

| Ruler | Length of reign | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kings from the SKL | ||||

| Anbu | 30 years | This name is also read as Ilshu.[126] | ||

| Anba | 17 years | His epithet was given as "the son of Anbu" on the list.[127] | ||

| Bazi | 30 years | His epithet was given as "the leatherworker" on the list.[127] | ||

| Zizi | 20 years | His epithet was given as "the fuller" on the list.[127] | ||

| Limer | 30 years | His epithet was given as "the 'gudug' priest" on the list.[note 16][127] | ||

| Sharrum-iter | 9 years | |||

|

"Then Mari was defeated and the kingship was taken to Kish.[127]" | ||||

|

The second kingdom | ||||

| Ikun-Shamash | Reigned before the reign of Ur-Nanshe of Lagash.[120] | |||

| Ikun-Shamagan | c. 2453 BC | His votive statue was discovered in Mari.[129] | ||

| Ansud | c. 2423-2416 BC | His name is inscribed on a jar (as Hanusum) sent to Mari by Mesannepada of Ur.[9][23] The name was read by Pettinato as Anubu.[20][130] | ||

| Saʿumu | c. 2416-2400 BC | He was attested in Enna-Dagan's letter as conquering many lands.[22] | ||

| Išhtup-Išar | c. 2400 BC | He was attested in Enna-Dagan's letter as conquering Emar and other Eblaite vassals.[22] | ||

| Ikun-Mari | This name is inscribed on a jar in Mari.[131] | |||

| Iblul-Il | c. 2380 BC | He forced Ebla to pay tribute.[22] | ||

| Nizi | His reign lasted three years.[132] | |||

| Enna-Dagan | c. 2340 BC | He wrote a letter to Irkab-Damu of Ebla to assert Mari's authority.[19] | ||

| Ikun-Ishar | c. 2320 BC | He is attested in the Eblaite archives.[133] | ||

| Hidar | c. 2300 BC | He is attested in the archives of Ebla, which was destroyed during his reign.[134] | ||

| Isqi-Mari | His name was previously read as Lamgi-Mari.[135] Hypothetically the last king.[29] | |||

|

The Shakkanakkus | ||||

| Ididish | c. 2266-2206 BC | |||

| Shu-Dagan | c. 2206-2200 BC | He was the son of Ididish.[42] | ||

| Ishme-Dagan | c. 2199-2154 BC | He ruled for 45 years.[41][136] | ||

| Nûr-Mêr | c. 2153-2148 BC | He was the son of Ishme-Dagan.[41] | ||

| Ishtup-Ilum | c. 2147-2136 BC | He was the brother of Nûr-Mêr.[41] | ||

| Ishgum-Addu | c. 2135-2127 BC | He reigned for eight years.[41] | ||

| Apîl-kîn | c. 2126-2091 BC | He was the son of Ishme-Dagan.[41][137] Used the royal title Lugal in his votive inscription.[138] | ||

| Iddin-El | c. 2090-2085 BC | His name is also read as Iddi-Ilum.[139] His name was inscribed on his votive statue.[140] | ||

| Ili-Ishar | c. 2084-2072 BC | His name is inscribed on a brick.[141] | ||

| Turam-Dagan | c. 2071-2051 BC | He was the son of Apîl-kîn and the brother of Ili-Ishar.[142] | ||

| Puzur-Ishtar | c. 2050-2025 BC | He was the son of Turam-Dagan.[41] Used the royal title.[143] | ||

| Hitlal-Erra | c. 2024-2017 BC | He was the son of Puzur-Ishtar.[144] Used the royal title.[143] | ||

| Hanun-Dagan | c. 2016-2008 BC | He was the son of Puzur-Ishtar.[145] Used the royal title.[143] | ||

| Isi-Dagan | c. 2000 BC | This name is inscribed on a seal.[146] | ||

| Ennin-Dagan | He was the son of Isi-Dagan.[147] | |||

| Itur-(...) | This name is damaged but could be Itur-Mer,[148] a gap separate him from Ennin-Dagan.[57] | |||

| Amer-Nunu | This name is inscribed on a seal.[149][150] | |||

| Tir-Dagan | He was the son of Itur-(...).[151] | |||

| Dagan-(...) | This name is damaged and is the last attested Shakkanakku.[152] | |||

|

The Lim dynasty | ||||

| Yaggid-Lim | c. 1830-1820 BC | He may have ruled in Suprum rather than in Mari.[62][65] | ||

| Yahdun-Lim | c. 1820-1798 BC | |||

| Sumu-Yamam | c. 1798-1796 BC | |||

|

Assyrian period | ||||

| Yasmah-Adad | c. 1796-1776 BC | He was the son of Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria.[76] | ||

| Ishar-Lim | c. 1776 BC | He was an Assyrian official who usurped the throne for a few months between Yasmah-Adad's escape and Zimri-Lim's arrival.[83] | ||

|

Lim restoration | ||||

| Zimri-Lim | c. 1776-1761 BC | |||

Culture and religion

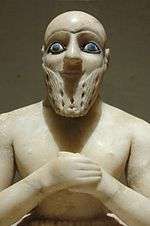

The first and second kingdoms were heavily influenced by the Sumerian south.[153] The society was led by an urban oligarchy,[154] and the citizens were well known for elaborate hair styles and dress.[155][156] The calendar was based on a solar year divided into twelve months, and was the same calendar used in Ebla "the old Eblaite calendar".[157][158] Scribes wrote in Sumerian language and the art was indistinguishable from Sumerian art, so was the architectural style.[159]

Mesopotamian influence continued to affect Mari's culture during the Amorite period,[160] which is evident in the Babylonian scribal style used in the city.[161] However, it was less influential than the former periods and a distinct Syrian style prevailed, which is noticeable in the seals of kings, which reflect a clear Syrian origin.[160] The society was a tribal one,[162] it consisted mostly of farmers and nomads (Haneans),[163] and in contrast to Mesopotamia, the temple had a minor role in everyday life as the power was mostly invested in the palace.[164] Women enjoyed a relative equality to men,[165] queen Shibtu ruled in her husband's name while he was away, and had an extensive administrative role and authority over her husband's highest officials.[166]

The Pantheon included both Sumerian and Semitic deities,[167] and throughout most of its history, Dagan was Mari's head of the Pantheon,[168][169] while Mer was the patron deity.[1] Other deities included the Semitic deities; Ishtar the goddess of fertility,[167] Athtar,[170] and Shamash, the Sun god who was regarded among the city most important deities,[171] and believed to be all-knowing and all-seeing.[172] Sumerian deities included Ninhursag,[167] Dumuzi,[173] Enki, Anu, and Enlil.[174] Prophecy had an important role for the society, temples included prophets,[175] who gave council to the king and participated in the religious festivals.[176] Ornina, the singer of Ishtar temple, was one of the oldest multi-talented women who has a prominent statue depicting her playing music during the reign of Iblul-Il.[177]

Economy

The first Mari provided the oldest wheels workshop to be discovered in Syria,[178] and was a center of bronze metallurgy.[3] The city also contained districts devoted to smelting, dyeing and pottery manufacturing,[4] charcoal was brought by river boats from the upper Khabur and Euphrates area.[3]

The second kingdom's economy was based on both agriculture and trade.[113] The economy was centralized and directed through a communal organization,[113] where grains were stored in communal granaries, and distributed amongst the population according to social statues.[113] The organization also controlled the animal herds in the kingdom.[113] Some people were directly connected to the palace instead of the communal organization, those included the metal and textile producers and the military officials.[113] Ebla was Mari's most important trading partner and rival,[179] Mari's position made it an important trading center as it controlled the road linking between the Levant and Mesopotamia.[180]

The Amorite Mari maintained the older aspects of the economy, which was still largely based on irrigated agriculture along the Euphrates valley.[113] The city kept its trading role and was a center for merchants from Babylonia and other kingdoms,[181] it received goods from the south and east through riverboats and distributed them north, north west and west.[182] The main merchandises handled by Mari were metals and tin imported from the Iranian Plateau and then exported west as far as Crete. Other goods included copper from Cyprus, silver from Anatolia, woods from Lebanon, gold from Egypt, olive oil, wine, and textiles in addition to precious stones from modern Afghanistan.[182]

Excavations and archive

Mari was discovered in 1933, on the eastern flank of Syria, near the Iraqi border.[183] A Bedouin tribe was digging through a mound called Tell Hariri for a gravestone that would be used for a recently deceased tribesman, when they came across a headless statue.[183] After the news reached the French authorities currently in control of Syria, the report was investigated, and digging on the site was started on December 14, 1933 by archaeologists from the Louvre in Paris.[183] Discoveries came quickly, with the temple of Ishtar being discovered in the next month.[93] Mari was classified by the archaeologists as the "most westerly outpost of Sumerian culture".[184]

Since the beginning of excavations, over 25,000 clay tablets in Akkadian language written in cuneiform were discovered.[93] Finds from the excavation are on display in the Louvre,[185][186] the National Museum of Aleppo,[187] the National Museum of Damascus,[172] and the Deir ez-Zor Museum. In the latter, the southern façade of the Court of the Palms room from Zimri-Lim's palace has been reconstructed, including the wall paintings.[188]

Mari has been excavated in annual campaigns between 1933-1939, 1951-1956, and since 1960,[189] and the first 21 seasons up to 1975 were led by André Parrot,[190] followed by Jean-Claude Margueron (until 2004),[191] and Pascal Butterlin (starting in 2005).[192] A journal devoted to the site since 1982, is Mari: Annales de recherches interdisciplinaires.[193][194] Archaeologists have tried to determine how many layers the site descends, according to French archaeologist André Parrot, "each time a vertical probe was commenced in order to trace the site's history down to virgin soil, such important discoveries were made that horizontal digging had to be resumed."[195]

Mari tablets

The tablets were written in Akkadian,[196] and they give informations about the kingdom, its customs, and the names of people who lived during that time.[60] More than 3000 are letters, the remainder includes administrative, economic, and judicial texts.[197] The tablets, according to André Parrot, "brought about a complete revision of the historical dating of the ancient Near East and provided more than 500 new place names, enough to redraw or even draw up the geographical map of the ancient world."[198] Almost all the tablets found were dated to the last 50 years of Mari's independence (c. 1800 – 1750 BC),[197] and most have now been published.[199] The language of the texts is official Akkadian but proper names and hints in syntax show that the common language of Mari's inhabitants was Northwest Semitic.[200]

Current situation

As a result of the Syrian Civil War, excavations stopped,[192] and the site came under the control of armed gangs, and witnessed a large scale looting. An official report revealed that the robbers are focusing on the royal palace, the public baths, the temple of Ishtar and the temple of Dagan.[201]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All of the dates in the article are estimated through the Middle chronology unless otherwise stated.

- ↑ French name that means the sacred inclosure.[12]

- ↑ In old readings, it was thought that Enna-Dagan was a general of Ebla. However, the deciphering of Ebla's tablets showed him in Mari and receiving gifts from Ebla during the reigns of his Mariote predecessors.[16]

- ↑ Irkab-Damu is not named in the letter but it is almost certain that he was the receiver of it.[18]

- ↑ Located 26 km west of Ar-Raqqah.[24]

- ↑ Located in the Euphrates middle valley close to Sweyhat.[25]

- ↑ According to Jean-Marie Durand, this Shakkanakku was appointed by Manishtushu, other opinions consider Naram-Sin as the appointer of Ididish.[39]

- ↑ This ruled out the former theory that there was an abandonment of Mari during the transition period.[50]

- ↑ Suprum is 12 kilometers upstream from Mari, perhaps the modern Tel Abu Hasan.[61]

- ↑ It is not certain that Yaggid-Lim controlled Mari, however he is traditionally considered the first king of the dynasty.[62]

- ↑ The credibility of the tablet is doubted as it was written by Yasmah-Adad who was Ila-kabkabu grandson.[62]

- ↑ The transition of the Lim family from Suprum to Mari could have been the work of Yahdun-Lim after the war with Ila-kabkabu.[65]

- ↑ Although officially a son of Yahdun-Lim, in reality he was a grandchild or nephew.[81]

- ↑ An ancient designation for the land that include the confluence of the Khabur and the Euphrates rivers.[103]

- ↑ Jean-Marie Durand, although not speculating the fate of the East-Semitic population, believe that the Akkadians during the Lim dynasty are not descended from the East-Semites of the Shakkanakku period.[108]

- ↑ Gudug was a rank in the hierarchy of the Mesopotamian temple workers, a guduj priest was not specialized to a certain deity cult, and served in many temples.[128]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Alberto Ravinell Whitney Green (2003). The Storm-god in the Ancient Near East. p. 62.

- ↑ Ulf Oldenburg (1969). Diss Ertationes : The Conflict Between El and Ba'al in Canaanite Religion. p. 60.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pierre-Louis Viollet (2007). Water Engineering in Ancient Civilizations: 5,000 Years of History. p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 136.

- 1 2 3 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 520.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 286.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 522.

- 1 2 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 267.

- 1 2 3 4 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 117.

- 1 2 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 523.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 524.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 137.

- 1 2 3 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 527.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 531.

- ↑ "Monuments of War, War of Monuments: Some Considerations on Commemorating War in the Third Millennium BC. Orientalia Vol.76/4". Davide Nadali. 2007. p. 354. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 817.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 463.

- 1 2 Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 26.

- 1 2 Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 200.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 57.

- ↑ Victor Harold Matthews, Don C. Benjamin (2006). Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East. p. 261.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 58.

- ↑ P.M. Michèle Daviau; Michael Weigl; John W. Wevers (2001). The World of the Aramaeans: Studies in Honour of Paul-Eugène Dion, Volume 1. p. 233.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 756.

- 1 2 Hartmut Kühne; Rainer Maria Czichon; Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). 4 ICAANE. p. 68.

- 1 2 Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 462.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 315.

- 1 2 "War of the lords. The battle of chronology - page.5". Joachim Bretschneider, Anne-Sophie Van Vyve, Greta Jans Leuven. 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Mario Liverani. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 208.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter. Eblaitica vol.4. p. 219.

- 1 2 "War of the lords. The battle of chronology - page.7". Joachim Bretschneider, Anne-Sophie Van Vyve, Greta Jans Leuven. 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ "Alfonso Archi and Maria Giovanna Biga, A Victory over Mari and the Fall of Ebla. Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 55, pp. 1-44". The American Schools of Oriental Research. 2003. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae; Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 339.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 123.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 75.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 71.

- 1 2 3 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 64.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (1993). Akkad: the first world empire : structure, ideology, traditions. p. 83.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Juan Oliva (2008). Textos para un historia política de Siria-Palestina I (in Spanish). p. 86.

- 1 2 Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 166.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 530.

- ↑ Matthew J. Suriano (2010). The Politics of Dead Kings: Dynastic Ancestors in the Book of Kings and Ancient Israel. p. 56.

- ↑ Eva Strommenger (1964). 5000 years of the art of Mesopotamia. p. 167.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 531.

- ↑ John L. McLaughlin (2012). The Ancient Near East. p. 2.

- ↑ Karel van Lerberghe; Gabriela Voet (1999). Languages and Cultures in Contact: At the Crossroads of Civilizations in the Syro-Mesopotamian Realm. p. 65.

- 1 2 3 Arne Wossink (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000-1600 BC). p. 31.

- ↑ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East. p. 10.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 18.

- 1 2 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 451.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 127.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 132.

- ↑ Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 256.

- 1 2 3 Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 597.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica vol.4. p. 139.

- ↑ Martin Sicker (2000). The Pre-Islamic Middle East. p. 25.

- 1 2 LaMoine F. DeVries (2006). Cities of the Biblical World: An Introduction to the Archaeology, Geography, and History of Biblical Sites. p. 27.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 673.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anne Porter (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. p. 31.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1999). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 601.

- 1 2 Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 257.

- 1 2 Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 86.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 603.

- 1 2 Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 606.

- ↑ Garth Fowden (2013). Before and After Muhammad: The First Millennium Refocused. p. 93.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 19.

- 1 2 Michael David Coogan (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. p. 68.

- ↑ Petrus Van Der Meer (1955). The Chronology of Ancient Western Asia and Egypt. p. 29.

- ↑ Dale Launderville (2003). Piety and Politics: The Dynamics of Royal Authority in Homeric Greece, Biblical Israel, and Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. p. 271.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 613.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 20.

- ↑ Marc Van De Mieroop (2007). A History of the Ancient Near East. p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East. p. 125.

- 1 2 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 452.

- ↑ Albert Kirk Grayson (1992). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions: From the beginning to Ashur-resha-ishi I. p. 27.

- ↑ Rivkah Harris (2003). Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia: The Gilgamesh Epic and Other Ancient Literature. p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. p. 254.

- ↑ Karen Radner; Eleanor Robson (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. p. 252.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 357.

- 1 2 Stephanie Dalley (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. p. 143.

- ↑ J. A. Emerton (1980). Prophecy: Essays presented to Georg Fohrer on his sixty-fifth birthday. p. 75.

- ↑ K. Van Der Toorn (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life. p. 101.

- ↑ J. R. Kupper (1963). Northern Mesopotamia and Syria. p. 11.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 329.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 687.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 45.

- ↑ Dominique Charpin (2012). Hammurabi of Babylon. p. 39.

- ↑ Ross Burns (2009). Monuments of Syria: A Guide. p. 198.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2013). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. p. 65.

- 1 2 3 William Henry (2006). Mary Magdalene: The Illuminator. p. 110.

- ↑ Judith Levin (2009). Hammurabi. p. 76.

- ↑ Judith Levin (2009). Hammurabi. p. 77.

- ↑ Marc Van De Mieroop (2008). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. p. 70.

- ↑ Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 271.

- ↑ Marc Van De Mieroop (2008). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. p. 75.

- ↑ Daniel E. Fleming (2012). The Legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible: History, Politics, and the Reinscribing of Tradition. p. 226.

- 1 2 Marc Van De Mieroop (2008). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. p. 76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 453.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. p. 201.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 408.

- ↑ Rebecca Hasselbach (2005). Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts. p. 3.

- ↑ Donald P. Hansen; Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 133.

- ↑ Sing C. Chew (2007). The Recurring Dark Ages: Ecological Stress, Climate Changes, and System Transformation. p. 67.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 469.

- 1 2 Wolfgang Heimpel (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. p. 21.

- ↑ Alfred Haldar (1971). Who Were the Amorites?, Volume 35. p. 8.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 222.

- ↑ Wolfgang Heimpel (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. p. 22.

- ↑ Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Liviu Giosan; Dorian Q. Fuller; Kathleen Nicoll; Rowan K. Flad; Peter D. Clift (2013). Climates, Landscapes, and Civilizations. p. 117.

- ↑ David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. p. 55.

- 1 2 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 223.

- ↑ Wolfgang Heimpel (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. p. 26.

- ↑ Samuel Edward Finer (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times: Ancient monarchies and empires. p. 173.

- 1 2 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 224.

- ↑ Charles Keith Maisels (2003). The Emergence of Civilisation: From Hunting and Gathering to Agriculture, Cities and the State of the Near East. p. 322.

- 1 2 Alfred Haldar (1971). Who Were the Amorites?, Volume 35. p. 16.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 739.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 742.

- 1 2 William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. p. 241.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 593.

- ↑ Stephen Bertman (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. p. 87.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. p. 329.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yoram Cohen (2013). Wisdom from the Late Bronze Age. p. 148.

- ↑ Jeremy Black (2004). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. p. 112.

- ↑ Robert D. Biggs (2008). Studies presented to Robert D. Biggs, June 4, 2004. p. 195.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 745.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 777.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 741.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 823.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). p. 827.

- ↑ Wolfgang Heimpel (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. p. 3.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 81.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 18.

- ↑ I. Tzvi Abusch; Carol Noyes (2001). Proceedings of the XLV Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale: historiography in the cuneiform world, Volume 2. p. 61.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 92.

- ↑ Claire, Iselin. "The Statuette of Iddi-Ilum". Musée du Louvre. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 78.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 168.

- 1 2 3 Juan Oliva (2008). Textos para un historia política de Siria-Palestina I (in Spanish). p. 91.

- ↑ Juan Oliva (2008). Textos para un historia política de Siria-Palestina I (in Spanish). p. 92.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 67.

- ↑ K. R. Veenhof; Jesper Eidem (2008). Mesopotamia: The Old Assyrian Period. p. 38.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 596.

- ↑ Gordon Douglas Young (1992). Mari in retrospect: fifty years of Mari and Mari studies. p. 158.

- ↑ Juan Oliva (2008). Textos para un historia política de Siria-Palestina I (in Spanish). p. 87.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 598.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 599.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 600.

- ↑ Brian M. Fagan; Charlotte Beck (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. p. 457.

- ↑ Daniel C. Snell (2008). A Companion to the Ancient Near East. p. 43.

- ↑ American Schools of Oriental Research (1984). The Biblical Archaeologist, Volume 47. p. 95.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 170.

- ↑ Giovanni Pettinato (1981). The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed in clay. p. 147.

- ↑ Mark E. Cohen (1993). The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. p. 23.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. p. 30.

- 1 2 Alberto Ravinell Whitney Green (2003). The Storm-god in the Ancient Near East. p. 161.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Kim Benzel; Jean M. Evans (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 16.

- ↑ Arne Wossink (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000-1600 BC). p. 126.

- ↑ Wolfgang Heimpel (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. p. 29.

- ↑ Lester L. Grabbe; Alice Ogden Bellis (2004). The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets. p. 3.

- ↑ Beth K. Dougherty; Edmund A. Ghareeb (2013). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. p. 657.

- ↑ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East. p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 90.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 304.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 171.

- ↑ Jonas Carl Greenfield, Ziony Zevit, Seymour Gitin, Michael Sokoloff (1995). Solving Riddles and Untying Knots: Biblical, Epigraphic, and Semitic Studies in Honor of Jonas C. Greenfield. p. 629.

- ↑ Lester L. Grabbe (2007). Ahab Agonistes: The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty. p. 245.

- 1 2 Diana Darke (2010). Syria. p. 293.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 92.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 170.

- ↑ Peter Machinist (2003). Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. p. 79.

- ↑ John H. Walton (1994). Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context: A Survey of Parallels Between Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Literature. p. 209.

- ↑ Ornina, The Singer of the Temple.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 521.

- ↑ Queens College, Jewish Studies Program and Center for Jewish Studies (2002). The Queens College Journal of Jewish Studies, Volume 4. p. 113.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 126.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Aubet (2013). Commerce and Colonization in the Ancient Near East. p. 141.

- 1 2 Beatrice Teissier (1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Stephanie Dalley (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. p. 10.

- ↑ I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond (1971). The Cambridge Ancient History. p. 97.

- ↑ "Statue of a lion, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia". the Louvre. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ "Collections & departments Department of Near Eastern Antiquities". the Louvre. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2013). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. p. 143.

- ↑ Dominik Bonatz; Hartmut Kühne; Asʻad Mahmoud; Matḥaf Dayr al-Zawr (1998). Rivers and steppes: cultural heritage and environment of the Syrian Jezireh : catalogue to the Museum of Deir ez-Zor.

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1995). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D. p. 272.

- ↑ Raggi-Verlag (1999). Antike Welt, Volume 30 (in German). p. 495.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 17.

- 1 2 محاضرة بالمركز الثقافي العربي السوري في باريس بمناسبة الذكرى الثمانين لإكتشاف ماري (in Arabic). Syrian Ministry of Culture. 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. p. 2.

- ↑ Jean Georges Heintz; Daniel Bodi; Lison Millot (1990). Bibliographie de Mari: archéologie et textes (1933-1988) (in French). p. 48.

- ↑ "Ancient Mesopotamian city in need of rescue". popular-archaeology, September 2011. 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa, Volume 4. p. 214.

- 1 2 Lester L. Grabbe; Alice Ogden Bellis (2004). The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets. p. 48.

- ↑ "Jack M. Sasson, The King and I a Mari King in Changing Perceptions. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 118, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1998), pp. 453-470". American Oriental Society. 1998. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. p. 63.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2013). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. p. 62.

- ↑ "The destruction of the idols: Syria's patrimony at risk from extremists". The Independent. 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G; Schwartz, Glenn M (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8.

- Aruz, Joan; Wallenfels, Ronald (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-588-39043-1.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-00292-2.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15908-6.

- Coogan, Michael David (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-21912-2.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-931956-02-4.

- Feliu, Lluís (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. Bill. ISBN 978-9-004-13158-3.

- Frayne, Douglas (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5873-7.

- Frayne, Douglas (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-442-69047-9.

- Green, Alberto Ravinell Whitney (2003). The Storm-god in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-069-9.

- Gordon, Cyrus; Rendsburg, Gary; Winter, Nathan (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.

- Heimpel, Wolfgang (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-575-06080-4.

- Kühne, Hartmut; Czichon, Rainer; Kreppner, Florian (2008). 4 ICAANE. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05757-8.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-78795-1.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- Podany, Amanda (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-79875-9.

- Viollet, Pierre-Louis (2007). Water Engineering in Ancient Civilizations: 5,000 Years of History. CRC Press. ISBN 978-9-078-04605-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mari. |

- Mari Mari passage on the Syrian ministry of culture website (in Arabic).

- Syrie - Mari Mari page on Britannica.

- Mari (Tell Hariri) Suggestion to have Mari (Tell Hariri) recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site, in 1999