Panama Canal

| Panama Canal Canal de Panamá | |

|---|---|

|

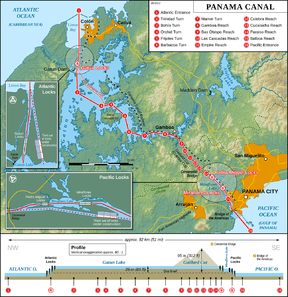

A schematic of the Panama Canal, illustrating the sequence of locks and passages | |

| Specifications | |

| Locks |

3 locks up, 3 down per transit; all three lanes (3 lanes of locks) |

| Status | Open, expansion opened June 26, 2016 |

| Navigation authority | Panama Canal Authority |

| History | |

| Original owner | La Société internationale du Canal |

| Principal engineer | John Findlay Wallace (1904–05), John Frank Stevens (1905–07), George Washington Goethals (1907–14) |

| Date of first use | August 15, 1914 |

The Panama Canal (Spanish: Canal de Panamá) is an artificial 48-mile (77 km) waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. There are locks at each end to lift ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial lake created to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal, 26 metres (85 ft) above sea level, and then lower the ships at the other end. The original locks are 33.5 metres (110 ft) wide. A third, wider lane of locks was constructed between September 2007 and May 2016. The expanded canal began commercial operation on June 26, 2016. The new locks allow transit of larger, Post-Panamax ships, capable of handling more cargo.[1]

France began work on the canal in 1881 but stopped due to engineering problems and a high worker mortality rate. The United States took over the project in 1904 and opened the canal on August 15, 1914. One of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken, the Panama Canal shortcut greatly reduced the time for ships to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, enabling them to avoid the lengthy, hazardous Cape Horn route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage or Strait of Magellan.

Colombia, France, and later the United States controlled the territory surrounding the canal during construction. The US continued to control the canal and surrounding Panama Canal Zone until the 1977 Torrijos–Carter Treaties provided for handover to Panama. After a period of joint American–Panamanian control, in 1999 the canal was taken over by the Panamanian government and is now managed and operated by the government-owned Panama Canal Authority.

Annual traffic has risen from about 1,000 ships in 1914, when the canal opened, to 14,702 vessels in 2008, for a total of 333.7 million Panama Canal/Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) tons. By 2012, more than 815,000 vessels had passed through the canal.[2] It takes six to eight hours to pass through the Panama Canal. The American Society of Civil Engineers has called the Panama Canal one of the seven wonders of the modern world.[3]

History

Early proposals in Panama

The earliest mention of a canal across the Isthmus of Panama dates back to 1534, when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, ordered a survey for a route through the Americas that would ease the voyage for ships traveling between Spain and Peru. Such a route would have given the Spanish a military advantage over the Portuguese.[4] In 1788, Thomas Jefferson suggested that the Spanish should create it since it would be a less treacherous route than going around the southern tip of South America, which tropical ocean currents would naturally widen thereafter.[5] During an expedition from 1788 to 1793, Alessandro Malaspina outlined plans for its construction.[6]

Given the strategic location of Panama and the potential offered by its narrow isthmus separating two great oceans, other trade links in the area were attempted over the years. The ill-fated Darien scheme was launched by the Kingdom of Scotland in 1698 to set up an overland trade route. Generally inhospitable conditions thwarted the effort, and it was abandoned in April 1700.[7]

Another effort was made in 1843. According to the New York Daily Tribune, August 24, 1843, a contract was entered into by Barings of London and the Republic of New Granada for the construction of a canal across the Isthmus of Darien (Isthmus of Panama). They referred to it as the Atlantic and Pacific Canal and it was a wholly British endeavor. It was expected to be completed in five years, but the plan was never carried out. At nearly the same time, other ideas were floated, including a canal (and/or a railroad) across Mexico's Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Nothing came of that plan either.[8])

In 1846 the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty granted the United States transit rights and the right to intervene militarily in the isthmus. In 1849, the discovery of gold in California created great interest in a crossing between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Panama Railway was built by the United States to cross the isthmus and opened in 1855. This overland link became a vital piece of western hemisphere infrastructure, greatly facilitating trade and largely determining the later canal route.

An all-water route between the oceans was still seen as the ideal solution, and in 1855 William Kennish, a Manx-born engineer working for the United States government, surveyed the isthmus and issued a report on a route for a proposed Panama Canal.[9] His report was published as a book entitled The Practicality and Importance of a Ship Canal to Connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[10]

In 1877 Armand Reclus, an officer with the French Navy, and Lucien Napoléon Bonaparte Wyse, both engineers, surveyed the route and published a French proposal for a canal.[11] French success in building the Suez Canal, while a lengthy project, encouraged planning for one to cross the isthmus.[12]

French construction attempts, 1881–94

The first attempt to construct a canal through what was then Colombia's province of Panama began on 1 January 1881. The project was inspired by the diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, who was able to raise considerable finance in France as a result of the huge profits generated by his successful construction of the Suez Canal.[13] Although the Panama Canal would eventually have to be only 40% as long as the Suez Canal, the former would prove to be far more of an engineering challenge, due to the tropical rain forests, the climate, the need for canal locks, and the lack of any ancient route to follow.

De Lesseps wanted a sea-level canal as at Suez but only visited the site a few times, during the dry season which lasts only four months of the year.[14] His men were totally unprepared for the rainy season, during which the Chagres River, where the canal started, became a raging torrent, rising up to 35 feet (10 m). The dense jungle was alive with venomous snakes, insects and spiders, but the worst aspect was the yellow fever and malaria (and other tropical diseases) which killed thousands of workers: by 1884 the death rate was over 200 per month.[15] Public health measures were ineffective because the role of the mosquito as a disease vector was then unknown. Conditions were downplayed in France to avoid recruitment problems,[16] but the high mortality rate made it difficult to maintain an experienced workforce.

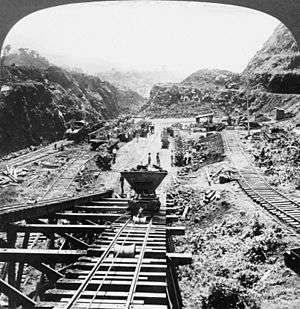

The main cut through the mountain at Culebra had to continually be widened, and the angle of its slopes reduced, to minimize landslides into the canal.[17] Steam shovels were used in the construction of the canal, and they were purchased from Bay City Industrial Works, a business owned by William L. Clements in Bay City, Michigan.[18] Other mechanical and electrical equipment was limited in its capabilities, and steel equipment rusted rapidly in the climate.[19]

In France, de Lesseps kept the investment and supply of workers flowing long after it was obvious that the targets were not being met, but eventually the money ran out. The French effort went bankrupt in 1889 after reportedly spending US$287,000,000 and losing an estimated 22,000 lives to disease and accidents, wiping out the savings of 800,000 investors.[16][20] Work was suspended on May 15, and in the ensuing scandal, known as the Panama affair, various of those deemed responsible were prosecuted, including Gustave Eiffel.[21] De Lesseps and his son Charles were found guilty of misappropriation of funds and sentenced to five years' imprisonment, though this was later overturned, and the father, at 88, was never imprisoned.[16]

In 1894, a second French company, the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama, was created to take over the project. A minimal workforce of a few thousand people was employed primarily to comply with the terms of the Colombian Panama Canal concession, to run the Panama Railroad, and to maintain the existing excavation and equipment in salable condition. The company sought a buyer for these assets, with an asking price of US$109,000,000. In the meanwhile they continued with enough activity to maintain their franchise, and Bunau-Varilla eventually managed to persuade de Lesseps that a lock-and-lake canal was more realistic than a sea-level canal.[22]

United States acquisition

At this time, the President and the Senate of the United States were interested in establishing a canal across the isthmus, with some favoring a canal across Nicaragua and others advocating the purchase of the French interests in Panama. The French manager of the New Panama Canal Company, Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, who was seeking American involvement, asked for $100 million, but accepted $40 million in the face of the Nicaraguan option. In June 1902, the U.S. Senate voted in favor of pursuing the Panamanian option, provided the necessary rights could be obtained, in the Spooner Act.[23]

On January 22, 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed by United States Secretary of State John M. Hay and Colombian Chargé Dr. Tomás Herrán. For $10 million and an annual payment it would have granted the United States a renewable lease in perpetuity from Colombia on the land proposed for the canal.[24] The treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate on March 14, 1903, but the Senate of Colombia did not ratify it. Bunau-Varilla told President Theodore Roosevelt and Hay of a possible revolt by Panamanian rebels who aimed to separate from Colombia, and hoped that the United States would support the rebels with U.S. troops and money. Roosevelt changed tactics, based in part on the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty of 1846, and actively supported the separation of Panama from Colombia and, shortly after recognizing Panama, signed a treaty with the new Panamanian government under similar terms to the Hay–Herrán Treaty.[25]

On November 2, 1903, U.S. warships blocked sea lanes for possible Colombian troop movements en route to put down the rebellion. Panama declared independence on November 3, 1903. The United States quickly recognized the new nation.[26] On November 6, 1903, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, as Panama's ambassador to the United States, signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, granting rights to the United States to build and indefinitely administer the Panama Canal Zone and its defenses. This is sometimes misinterpreted as the "99-year lease" because of misleading wording included in article 22 of the agreement.[27] Almost immediately, the treaty was condemned by many Panamanians as an infringement on their country's new national sovereignty.[28][29] This would later become a contentious diplomatic issue among Colombia, Panama, and the United States.

President Roosevelt famously stated that "I took the Isthmus, started the canal and then left Congress not to debate the canal, but to debate me." Several parties in the United States called this an act of war on Colombia: The New York Times called the support given by the United States to Mr. Bunau-Varilla an "act of sordid conquest." The New York Evening Post called it a "vulgar and mercenary venture." More recently, historian George Tindall labeled it "one of the greatest blunders in American foreign policy." It is often cited as the classic example of U.S. gunboat diplomacy in Latin America, and the best illustration of what Roosevelt meant by the old African adage, "speak softly and carry a big stick [and] you will go far." After the revolution in 1903, the Republic of Panama became a U.S. protectorate until 1939.[30]

Thus in 1904, the United States purchased the French equipment and excavations, including the Panama Railroad, for US$40 million, of which $30 million related to excavations completed, primarily in the Gaillard Cut (then called the Culebra Cut), valued at about $1.00 per cubic yard.[31] The United States also paid the new country of Panama $10 million and a $250,000 payment each following year.

In 1921, Colombia and the United States entered into the Thomson-Urrutia Treaty, in which the United States agreed to pay Colombia $25 million: $5 million upon ratification, and four-$5 million annual payments, and grant Colombia special privileges in the Canal Zone. In return, Colombia recognized Panama as an independent nation.

United States construction of the Panama canal, 1904–14

The U.S. formally took control of the canal property on May 4, 1904, inheriting from the French a depleted workforce and a vast jumble of buildings, infrastructure and equipment, much of it in poor condition. A U.S. government commission, the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC), was established to oversee construction[32] and was given control of the Panama Canal Zone, over which the United States exercised sovereignty. The commission reported directly to Secretary of War William Howard Taft and was directed to avoid the inefficiency and corruption that had plagued the French 15 years earlier.

On May 6, 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed John Findley Wallace, formerly chief engineer and finally general manager of the Illinois Central Railroad, as chief engineer of the Panama Canal Project. Overwhelmed by the disease-plagued country and forced to use often dilapidated French infrastructure and equipment,[33] as well as being frustrated by the overly bureaucratic ICC, Wallace resigned abruptly in June 1905.[34] He was succeeded by John Frank Stevens, a self-educated engineer who had built the Great Northern Railroad.[35] Stevens was not a member of the ICC; he increasingly viewed its bureaucracy as a serious hindrance, bypassing the commission and sending requests and demands directly to the Roosevelt Administration in Washington.

One of Stevens' first achievements in Panama was in building and rebuilding the housing, cafeterias, hotels, water systems, repair shops, warehouses, and other infrastructure needed by the thousands of incoming workers. Stevens began the recruitment effort to entice thousands of workers from the United States and other areas to come to the Canal Zone to work, and tried to provide accommodation in which the incoming workers could work and live in reasonable safety and comfort. He also re-established and enlarged the railway that was to prove crucial in transporting millions of tons of soil from the cut through the mountains to the dam across the Chagres River.

Colonel William C. Gorgas had been appointed chief sanitation officer of the canal construction project in 1904. Gorgas implemented a range of measures to minimize the spread of deadly diseases, particularly yellow fever and malaria which had recently been shown to be mosquito-borne following the work of Dr. Carlos Finlay and Dr. Walter Reed.[36] There was investment in extensive sanitation projects, including city water systems, fumigation of buildings, spraying of insect-breeding areas with oil and larvicide, installation of mosquito netting and window screens, and elimination of stagnant water. Despite opposition from the Commission (one member said his ideas were barmy), Gorgas persisted and when Stevens arrived, he threw his weight behind the project. After two years of extensive work, the mosquito-spread diseases were nearly eliminated.[37] Nevertheless, even with all this effort, about 5,600 workers died of disease and accidents during the U.S. construction phase of the canal.

In 1905, a U.S. engineering panel was commissioned to review the canal design, which still had not been finalized. It recommended to President Roosevelt a sea-level canal, as had been attempted by the French. However, in 1906 Stevens, who had seen the Chagres in full flood, was summoned to Washington and declared a sea-level approach to be "an entirely untenable proposition". He argued in favor of a canal using a lock system to raise and lower ships from a large reservoir 85 ft (26 m) above sea level. This would create both the largest dam (Gatun Dam) and the largest man-made lake (Gatun Lake) in the world at that time. The water to refill the locks would be taken from Gatun Lake by opening and closing enormous gates and valves and letting gravity propel the water from the lake. Gatun Lake would connect to the Pacific through the mountains at the Gaillard (Culebra) Cut. Stevens successfully convinced Roosevelt of the necessity and feasibility of the alternative scheme.[38]

The construction of a canal with locks required the excavation of more than 170,000,000 cu yd (129,974,326 m3) of material over and above the 30,000,000 cu yd (22,936,646 m3) excavated by the French. As quickly as possible, the Americans replaced or upgraded the old, unusable French equipment with new construction equipment that was designed for a much larger and faster scale of work. About 102 new large, railroad-mounted steam shovels were purchased from the Marion Power Shovel Company and brought from the United States. These were joined by enormous steam-powered cranes, giant hydraulic rock crushers, cement mixers, dredges, and pneumatic power drills, nearly all of which were manufactured by new, extensive machine-building technology developed and built in the United States. The railroad also had to be comprehensively upgraded with heavy-duty, double-tracked rails over most of the line to accommodate new rolling stock. In many places, the new Gatun Lake flooded over the original rail line, and a new line had to be constructed above Gatun Lake's waterline.

In 1907, Stevens resigned as chief engineer, having in his view made success certain.[39] His replacement, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt, was U.S. Army Major George Washington Goethals of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (soon to be promoted to lieutenant colonel and later to colonel), a strong, United States Military Academy–trained leader and civil engineer with experience of canals (unlike Stevens). Goethals would direct the work in Panama to a successful conclusion.[40]

Goethals divided the engineering and excavation work into three divisions: Atlantic, Central, and Pacific. The Atlantic Division, under Major William L. Sibert, was responsible for construction of the massive breakwater at the entrance to Limon Bay, the Gatun locks and their 5.6 km (3.5 mi) approach channel, and the immense Gatun Dam. The Pacific Division, under Sydney B. Williamson (the only civilian member of this high-level team), was similarly responsible for the Pacific 4.8 km (3.0 mi) breakwater in Panama Bay, the approach channel to the locks, and the Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks and their associated dams and reservoirs.[41]

The Central Division, under Major David du Bose Gaillard of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, was assigned one of the most difficult parts: excavating the Culebra Cut through the continental divide to connect Gatun Lake to the Pacific Panama Canal locks.[42]

On October 10, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson sent a signal from the White House by telegraph which triggered the explosion that destroyed the Gamboa Dike. This flooded the Culebra Cut, thereby joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[43] Alexandre La Valley (a floating crane built by Lobnitz & Company, and launched in 1887) was the first self-propelled vessel to transit the canal from ocean to ocean. This vessel crossed the canal from the Atlantic in stages during construction, finally reaching the Pacific on January 7, 1914.[44] SS Cristobal (a cargo and passenger ship built by Maryland Steel, and launched in 1902 as SS Tremont) was the first ship to transit the canal from ocean to ocean on August 3, 1914.[45]

The construction of the canal was completed in 1914, 401 years after Panama was first crossed by Vasco Núñez de Balboa. The United States spent almost $375,000,000 (roughly equivalent to $8,600,000,000 now[46]) to finish the project. This was by far the largest American engineering project to date. The canal was formally opened on August 15, 1914, with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon.[47]

The opening of Panama Canal in 1914 caused a severe drop in traffic along Chilean ports due to shifts in the maritime trade routes.[48][49][50]

A Marion steam shovel excavating the Panama Canal in 1908 |

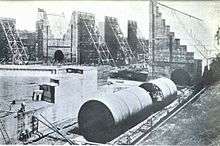

The Panama Canal locks under construction in 1910 |

SS Ancon passing through the canal on 15 August 1914, the first ship to do so |

Throughout this time, Ernest "Red" Hallen was hired by the Isthmian Canal Commission to document the progress of the work.

Later developments

By the 1930s it was seen that water supply would be an issue for the canal; this prompted the building of the Madden Dam across the Chagres River above Gatun Lake. The dam, completed in 1935, created Madden Lake (later Alajuela Lake), which provides additional water storage for the canal.[51] In 1939, construction began on a further major improvement: a new set of locks for the canal, large enough to carry the larger warships that the United States was building at the time and planned to continue building. The work proceeded for several years, and significant excavation was carried out on the new approach channels, but the project was canceled after World War II.[52][53]

|

Statement on the Panama Canal Treaty Signing

Jimmy Carter's speech upon signing the Panama Canal treaty, 7 September 1977 |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

After World War II, U.S. control of the canal and the Canal Zone surrounding it became contentious; relations between Panama and the United States became increasingly tense. Many Panamanians felt that the Canal Zone rightfully belonged to Panama; student protests were met by the fencing-in of the zone and an increased military presence there.[54] Demands for the United States to hand over the canal to Panama increased after the Suez Crisis in 1956, when the United States used financial and diplomatic pressure to force France and the UK to abandon their attempt to retake control of the Suez Canal, previously nationalized by the Nasser regime in Egypt. Unrest culminated in riots on Martyr's Day, January 9, 1964, when about 20 Panamanians and 3–5 U.S. soldiers were killed.

A decade later, in 1974, negotiations toward a settlement began and resulted in the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. On September 7, 1977, the treaty was signed by President of the United States Jimmy Carter and Omar Torrijos, de facto leader of Panama. This mobilized the process of granting the Panamanians free control of the canal so long as Panama signed a treaty guaranteeing the permanent neutrality of the canal. The treaty led to full Panamanian control effective at noon on December 31, 1999, and the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) assumed command of the waterway. The Panama Canal remains one of the chief revenue sources for Panama.

Before this handover, the government of Panama held an international bid to negotiate a 25-year contract for operation of the container shipping ports located at the canal's Atlantic and Pacific outlets. The contract was not affiliated with the ACP or Panama Canal operations and was won by the firm Hutchison Whampoa, a Hong Kong–based shipping interest owned by Li Ka-shing.

Canal

Layout

| Panama Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While globally the Atlantic Ocean is east of the isthmus and the Pacific is west, the general direction of the canal passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific is from northwest to southeast. This is because of a local anomaly in the shape of the isthmus at the point the canal occupies. The Bridge of the Americas (Spanish: Puente de las Américas) at the Pacific side is about a third of a degree east of the Colón end on the Atlantic side.[56] Still, in formal nautical communications, the simplified directions "Southbound" and "Northbound" are used.

The canal consists of artificial lakes, several improved and artificial channels, and three sets of locks. An additional artificial lake, Alajuela Lake (known during the American era as Madden Lake), acts as a reservoir for the canal. The layout of the canal as seen by a ship passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific is as follows:[57]

- From the formal marking line of the Atlantic Entrance, one enters Limón Bay (Bahía Limón), a large natural harbour. The entrance runs 8.7 km (5.4 mi). It provides a deepwater port (Cristóbal), with facilities like multimodal cargo exchange (to and from train) and the Colón Free Trade Zone (a free port).

- A 2.0 mi (3.2 km) channel forms the approach to the locks from the Atlantic side.

- The Gatun Locks, a three-stage flight of locks 1.9 km (1.2 mi) long, lifts ships to the Gatun Lake level, some 26.5 m (87 ft) above sea level.

- Gatun Lake, an artificial lake formed by the building of the Gatun Dam, carries vessels 24.2 km (15 mi) across the isthmus. It is the summit canal stretch, fed by the Gatun River and emptied by basic lock operations.

- From the lake, the Chagres River, a natural waterway enhanced by the damming of Gatun Lake, runs about 8.5 km (5.3 mi). Here the upper Chagres River feeds the high level canal stretch.

- The Culebra Cut slices 12.6 km (7.8 mi) through the mountain ridge, crosses the continental divide and passes under the Centennial Bridge.

- The single-stage Pedro Miguel Lock, which is 1.4 km (0.87 mi) long, is the first part of the descent with a lift of 9.5 m (31 ft).

- The artificial Miraflores Lake, 1.7 km (1.1 mi) long, and 16.5 m (54 ft) above sea level.

- The two-stage Miraflores Locks, is 1.7 km (1.1 mi) long, with a total descent of 16.5 m (54 ft) at mid-tide.

- From the Miraflores Locks one reaches Balboa harbour, again with multimodal exchange provision (here the railway meets the shipping route again). Nearby is Panama City.

- From this harbour an entrance/exit channel leads to the Pacific Ocean (Gulf of Panama), 13.2 km (8.2 mi) from the Miraflores Locks, passing under the Bridge of the Americas.

Thus, the total length of the canal is 77.1 km (48 mi).

Navigation

Gatun Lake

Artificially created in 1913 by damming the Chagres River, Gatun Lake is an essential part of the Panama Canal, providing the millions of gallons of water necessary to operate the Panama Canal locks each time a ship passes through. At the time it was formed, Gatun Lake was the largest man-made lake in the world. The impassable rainforest around the lake has been the best defense of the Panama Canal. Today these areas remain practically unscathed by human interference and are one of the few accessible areas where various native Central American animal and plant species can be observed undisturbed in their natural habitat.

The largest island on Gatun Lake is Barro Colorado Island. It was established for scientific study when the lake was formed, and is operated by the Smithsonian Institution. Many important scientific and biological discoveries of the tropical animal and plant kingdom originated here. Gatun Lake covers about 470 square kilometres (180 sq mi), a vast tropical ecological zone and part of the Atlantic Forest Corridor. Ecotourism on the lake has become an industry for Panamanians.

Gatun Lake also provides drinking water for Panama City and Colón. Fishing is one of the primary recreational pursuits on Gatun Lake. Non-native peacock bass were introduced by accident to Gatun Lake around 1967[58] by a local businessman,[59] and have since flourished to become the dominant angling game fish in Gatun Lake. Locally called Sargento and believed to be the species Cichla pleiozona,[60] these peacock bass originate from the Amazon, Rio Negro, and Orinoco river basins, where they are considered a premier game fish.

Lock size

The size of the locks determines the maximum size ship that can pass through. Because of the importance of the canal to international trade, many ships are built to the maximum size allowed. These are known as Panamax vessels. A Panamax cargo ship typically has a deadweight tonnage (DWT) of 65,000–80,000 tonnes, but its actual cargo is restricted to about 52,500 tonnes because of the 12.6 m (41.2 ft) draft restrictions within the canal.[61] The longest ship ever to transit the canal was the San Juan Prospector (now Marcona Prospector), an ore-bulk-oil carrier that is 296.57 m (973 ft) long with a beam of 32.31 m (106 ft).[62]

Initially the locks at Gatun were designed to be 28.5 m (94 ft) wide. In 1908, the United States Navy requested that an increased width of at least 36 m (118 ft) to allow the passage of U.S. Naval ships. Eventually a compromise was made and the locks were built 33.53 m (110.0 ft) wide. Each lock is 320 m (1,050 ft) long, with the walls ranging in thickness from 15 m (49 ft) at the base to 3 m (9.8 ft) at the top. The central wall between the parallel locks at Gatun is 18 m (59 ft) thick and over 24 m (79 ft) high. The steel lock gates measure an average of 2 m (6.6 ft) thick, 19.5 m (64 ft) wide, and 20 m (66 ft) high.[63] It is the size of the locks, specifically the Pedro Miguel Locks, along with the height of the Bridge of the Americas at Balboa, that determine the Panamax metric and limit the size of ships that may use the canal.

The 2006 third set of locks project has created larger locks, allowing bigger ships to transit through deeper and wider channels. The allowed dimensions of ships using these locks increased by 25% in length, 51% in beam, and 26% in draft, as defined by New Panamax metrics.[64]

Tolls

Tolls for the canal are set by the Panama Canal Authority and are based on vessel type, size, and the type of cargo.[65]

For container ships, the toll is assessed on the ship's capacity expressed in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), one TEU being the size of a standard intermodal shipping container. Effective April 1, 2016, this toll went from US$74.00 per loaded container to $60.00 per TEU capacity plus $30.00 per loaded container for a potential $90 per TEU when the ship is full. A Panamax container ship may carry up to 4,400 TEU. The toll is calculated differently for passenger ships and for container ships carrying no cargo ("in ballast"). As of April 1, 2016, the ballast rate is US$60.00, down from US$65.60 per TEU.

Passenger vessels in excess of 30,000 tons (PC/UMS), known popularly as cruise ships, pay a rate based on the number of berths, that is, the number of passengers that can be accommodated in permanent beds. The per-berth charge since April 1, 2016 is $111 for unoccupied berths and $138 for occupied berths in the Panamax locks. Started in 2007, this fee has greatly increased the tolls for such ships.[66] Passenger vessels of less than 30,000 tons or less than 33 tons per passenger are charged according to the same per-ton schedule as are freighters. Almost all major cruise ships have more than 33 tons per passenger; the rule of thumb for cruise line comfort is generally given as a minimum of 40 tons per passenger.

Most other types of vessel pay a toll per PC/UMS net ton, in which one "ton" is actually a volume of 100 cubic feet (2.83 m3). (The calculation of tonnage for commercial vessels is quite complex.) As of fiscal year 2016, this toll is US$5.25 per ton for the first 10,000 tons, US$5.14 per ton for the next 10,000 tons, and US$5.06 per ton thereafter. As with container ships, reduced tolls are charged for freight ships "in ballast", $4.19, $4.12, $4.05 respectively.

On 1 April 2016 a more complicated toll system was introduced, having the neopanamax locks at a higher rate in some cases, natural gas transport as a new separate category and other changes.(see tolls, check preface for symbols explaining changes.)

Small (less than 125 ft) vessels up to 583 PC/UMS net tons when carrying passengers or cargo, or up to 735 PC/UMS net tons when in ballast, or up to 1,048 fully loaded displacement tons, are assessed minimum tolls based upon their length overall, according to the following table (as of 29 April 2015):

| Length of vessel | Toll |

|---|---|

| Up to 15.240 meters (50 ft) | US$800 |

| More than 15.240 meters (50 ft) up to 24.384 meters (80 ft) | US$1,300 |

| More than 24.384 meters (80 ft) up to 30.480 meters (100 ft) | US$2,000 |

| More than 30.480 meters (100 ft) | US$3,200 plus $72/TEU |

Morgan Adams of Los Angeles, California, holds the distinction of paying the first toll received by the United States Government for the use of the Panama Canal by a pleasure boat. His boat Lasata passed through the Zone on August 14, 1914. The crossing occurred during a 6,000-mile sea voyage from Jacksonville, Florida, to Los Angeles in 1914.

The most expensive regular toll for canal passage to date was charged on April 14, 2010 to the cruise ship Norwegian Pearl, which paid US$375,600.[67][68] The average toll is around US$54,000. The highest fee for priority passage charged through the Transit Slot Auction System was US$220,300, paid on August 24, 2006, by the Panamax tanker Erikoussa,[69] bypassing a 90-ship queue waiting for the end of maintenance work on the Gatun Locks, and thus avoiding a seven-day delay. The normal fee would have been just US$13,430.[70]

The lowest toll ever paid was 36 cents, by American Richard Halliburton who swam the Panama Canal in 1928.[71]

Issues leading to expansion

In the 100 years since its opening, the canal continues to enjoy great success. Even though world shipping—and the size of ships themselves—has changed markedly since the canal was designed, it continues to be a vital link in world trade, carrying more cargo than ever before, with fewer overhead costs. Nevertheless, the canal faces a number of potential concerns.

Efficiency and maintenance

Opponents to the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties feared that efficiency and maintenance would suffer following the U.S. withdrawal from the Panama Canal Zone; however, this has been proven not to be the case. Capitalizing on practices developed during the American administration, canal operations are improving under Panamanian control.[72] Canal Waters Time (CWT), the average time it takes a vessel to navigate the canal, including waiting time, is a key measure of efficiency; according to the ACP, since 2000, it has ranged between 20 and 30 hours. The accident rate has also not changed appreciably in the past decade, varying between 10 and 30 accidents each year from about 14,000 total annual transits.[73][74][75] An official accident is one in which a formal investigation is requested and conducted.

Increasing volumes of imports from Asia, which previously landed on U.S. West Coast ports, are now passing through the canal to the American East Coast.[76] The total number of ocean-going transits increased from 11,725 in 2003 to 13,233 in 2007, falling to 12,855 in 2009. (The canal's fiscal year runs from October through September.)[77] This has been coupled with a steady rise in average ship size and in the numbers of Panamax vessels passing through the canal, so that the total tonnage carried rose from 227.9 million PC/UMS tons in fiscal year 1999 to a then record high of 312.9 million tons in 2007, and falling to 299.1 million tons in 2009.[56][77] Tonnage for fiscal 2013, 2014 and 2015 was 320.6, 326.8 and 340.8 million PC/UMS tons carried on 13,660, 13,481 and 13,874 transits respectively.[78] The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) has invested nearly US$1 billion in widening and modernizing the canal, with the aim of increasing capacity by 20%.[79] The ACP cites a number of major improvements, including the widening and straightening of the Gaillard Cut to reduce restrictions on passing vessels, the deepening of the navigational channel in Gatun Lake to reduce draft restrictions and improve water supply, and the deepening of the Atlantic and Pacific entrances to the canal. This is supported by new equipment, such as a new drill barge and suction dredger, and an increase of the tug boat fleet by 20%. In addition, improvements have been made to the canal's operating machinery, including an increased and improved tug locomotive fleet, the replacement of more than 16 km (10 mi) of locomotive track, and new lock machinery controls. Improvements have been made to the traffic management system to allow more efficient control over ships in the canal.[80]

In December 2010, record-breaking rains caused a 17-hour closure of the canal; this was the first closure since the United States invasion of Panama in 1989.[81][82] The rains also caused an access road to the Centenario Bridge to collapse.[83][84][85][86]

Capacity

The canal is currently handling more vessel traffic than had ever been envisioned by its builders. In 1934 it was estimated that the maximum capacity of the canal would be around 80 million tons per year;[87] as noted above, canal traffic in 2015 reached 340.8 million tons of shipping.

To improve capacity, a number of improvements have been made to the current canal system. These improvements aim to maximize the possible use of current locking system:[88]

- Implementation of an enhanced locks lighting system;

- Construction of two tie-up stations in Gaillard Cut;

- Widening Gaillard Cut from 192 to 218 meters (630 to 715 ft);

- Improvements to the tugboat fleet;

- Implementation of the carousel lockage system in Gatun locks;

- Development of an improved vessel scheduling system;

- Deepening of Gatun Lake navigational channels from 10.4 to 11.3 meters (34 to 37 ft) PLD;

- Modification of all locks structures to allow an additional draft of about 0.30 meters (1 ft);

- Deepening of the Pacific and Atlantic entrances;

- Construction of a new spillway in Gatun, for flood control.

These improvements enlarged the capacity from 300 million PCUMS (2008) to 340 PCUMS (2012). It should be noted that these improvements were started before the new locks project, and are complementary to it.

Competition

Despite having enjoyed a privileged position for many years, the canal is increasingly facing competition from other quarters. Because canal tolls have risen as ships have become larger, some critics[89] have suggested that the Suez Canal is now a viable alternative for cargo en route from Asia to the U.S. East Coast.[90] The Panama Canal, however, continues to serve more than 144 of the world's trade routes and the majority of canal traffic comes from the "all-water route" from Asia to the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts.

On June 15, 2013, Nicaragua awarded the Hong Kong-based HKND Group a 50-year concession to develop a canal through the country.[91]

The increasing rate of melting of ice in the Arctic Ocean has led to speculation that the Northwest Passage or Arctic Bridge may become viable for commercial shipping at some point in the future. This route would save 9,300 km (5,800 mi) on the route from Asia to Europe compared with the Panama Canal, possibly leading to a diversion of some traffic to that route. However, such a route is beset by unresolved territorial issues and would still hold significant problems owing to ice.[92]

Water issues

Gatun Lake is filled with rainwater, and the lake accumulates excess water during wet months. The water is lost to the oceans at a rate of 101,000 m3 (26,700,000 US gal; 22,200,000 imp gal) per downward lock cycle. Since a ship will have to go upward to Gatun Lake first and then descend, a single passing will cost double the amount; but the same waterflow cycle can be used for another ship passing in the opposite direction. The ship's submerged volume is not relevant to this amount of water.[93][94] During the dry season, when there is less rainfall, there is also a shortfall of water in Gatun Lake.

As a signatory to the United Nations Global Compact and member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the ACP has developed an environmentally and socially sustainable program for expansion, which will protect the aquatic and terrestrial resources of the canal watershed. After completion, expansion will guarantee the availability and quality of water resources by using water-saving basins at each new lock. These water-saving basins will diminish water loss and preserve freshwater resources along the waterway by reusing water from the basins into the locks. Each lock chamber will have three water-saving basins, which will reuse 60% of the water in each transit. There are a total of nine basins for each of the two lock complexes, and a total of 18 basins for the entire project.

The sea level at the Pacific side is about 20 cm (8 in) higher than that of the Atlantic side due to differences in ocean conditions such as water densities and weather.[95]

Third set of locks project

As demand is rising for efficient global shipping of goods, the canal is positioned to be a significant feature of world shipping for the foreseeable future. However, changes in shipping patterns —particularly the increasing numbers of larger-than-Panamax ships— necessitated changes to the canal for it to retain a significant market share. In 2006 it was anticipated that by 2011, 37% of the world's container ships would be too large for the present canal, and hence a failure to expand would result in a significant loss of market share. The maximum sustainable capacity of the original canal, given some relatively minor improvement work, was estimated at 340 million PC/UMS tons per year; it was anticipated that this capacity would be reached between 2009 and 2012. Close to 50% of transiting vessels were already using the full width of the locks.[96]

An enlargement scheme similar to the 1939 Third Lock Scheme, to allow for a greater number of transits and the ability to handle larger ships, had been under consideration for some time,[97] was approved by the government of Panama,[98][99] The cost was estimated at US$5.25 billion, and the expansion allowed to double the canal's capacity, allowing more traffic and the passage of longer and wider Post-Panamax ships. The proposal to expand the canal was approved in a national referendum by about 80% on October 22, 2006.[100] The canal expansion was built between 2007 and 2016, though completion was originally expected by the end of 2014.[1]

The expansion plan had two new flights of locks built parallel to, and operated in addition to, the old locks: one east of the existing Gatun locks, and one southwest of the Miraflores locks, each supported by approach channels. Each flight ascends from sea level directly to the level of Gatun Lake; the existing two-stage ascent at Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks was not replicated. The new lock chambers feature sliding gates, doubled for safety, and are 427 m (1,400 ft) long, 55 m (180 ft) wide, and 18.3 m (60 ft) deep. This allows the transit of vessels with a beam of up to 49 m (160 ft), an overall length of up to 366 m (1,200 ft) and a draft of up to 15 m (49 ft), equivalent to a container ship carrying around 12,000 containers, each 6.1 m (20 ft) in length (TEU).

The new locks are supported by new approach channels, including a 6.2 km (3.9 mi) channel at Miraflores from the locks to the Gaillard Cut, skirting Miraflores Lake. Each of these channels are 218 m (720 ft) wide, which will require post-Panamax vessels to navigate the channels in one direction at a time. The Gaillard Cut and the channel through Gatun Lake were widened to at least 280 m (920 ft) on the straight portions and at least 366 m (1,200 ft) on the bends. The maximum level of Gatun Lake was raised from 26.7 m (88 ft) to 27.1 m (89 ft).

Each flight of locks is accompanied by nine water reutilization basins (three per lock chamber), each basin being about 70 m (230 ft) wide, 430 m (1,400 ft) long and 5.50 m (18 ft) deep. These gravity-fed basins allow 60% of the water used in each transit to be reused; the new locks consequently use 7% less water per transit than each of the existing lock lanes. The deepening of Gatun Lake and the raising of its maximum water level also provide capacity for significantly more water storage. These measures are intended to allow the expanded canal to operate without constructing new reservoirs.

The estimated cost of the project is US$5.25 billion. The project was designed to allow for an anticipated growth in traffic from 280 million PC/UMS tons in 2005 to nearly 510 million PC/UMS tons in 2025. The expanded canal will have a maximum sustainable capacity of about 600 million PC/UMS tons per year. Tolls will continue to be calculated based on vessel tonnage, and in some cases depend on the locks used.

An article in the February 2007 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine described the plans for the canal expansion, focusing on the engineering aspects of the expansion project.[101] There is also a follow-up article in the February 2010 issue of Popular Mechanics.[102]

On September 3, 2007, thousands of Panamanians stood across from Paraíso Hill in Panama to witness a huge initial explosion and launch of the Expansion Program. The first phase of the project was the dry excavations of the 218 meters (715 feet) wide trench connecting the Gaillard Cut with the Pacific coast, removing 47 million cubic meters of earth and rock.[103] By June 2012, a 30 m reinforced concrete monolith had been completed, the first of 46 such monoliths which will line the new Pacific-side lock walls.[104] By early July 2012, however, it was announced that the canal expansion project had fallen six months behind schedule, leading expectations for the expansion to open in April 2015 rather than October 2014, as originally planned.[105] By September 2014, the new gates were projected to be open for transit at the "beginning of 2016."[106][107][108][109]

It was announced in July 2009 that the Belgian dredging company Jan De Nul, together with a consortium of contractors consisting of the Spanish Sacyr Vallehermoso, the Italian Impregilo, and the Panamanian company Grupo Cusa, had been awarded the contract to build the six new locks for $US3.1 billion, which was one billion less than the next highest competing bid due to having a concrete budget 71% percent smaller than that of the next bidder and allotted roughly 25% less for steel to reinforce that concrete. The contract resulted in $100 million in dredging works over the next few years for the Belgian company and a great deal of work for its construction division. The design of the locks is a carbon copy of the Berendrecht Lock, which is 68 m wide and 500 m long, making it the largest lock in the world. Completed in 1989 by the Port of Antwerp, which De Nul helped build, the company still has engineers and specialists who were part of that project.[110]

In January 2014, a contract dispute threatened the progress of the project.[111][112] There was a delay of less than two months however, with work by the consortium members reaching goals by June 2014.[113][114]

In June 2015, flooding of the new locks began: first on the Atlantic side, then on the Pacific; by then, the canal's re-inauguration was slated for April 2016.[115][116][117] On March 23, 2016, the expansion inauguration was set for June 26, 2016.[118]

The new locks opened for commercial traffic on 26 June 2016, and the first ship to cross the canal using the third set of locks was a modern New Panamax vessel, the Chinese-owned container ship Cosco Shipping Panama.[1] The original locks, now over 100 years old, allow engineers greater access for maintenance, and are projected to continue operating indefinitely.[96]

The total cost is unknown since the expansion's contractors are seeking at least an addition US$3.4 billion from the canal authority due to excess expenses.[119]

Rival Colombia rail link

China is investigating a proposal to construct a 220 km (137 mi) railway between Colombia's Pacific and Caribbean coasts.[120][121][122][123]

Rival Nicaragua canal

On July 7, 2014, Wang Jing, chairman of the HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Co. Ltd. (HKND Group) advised that a route for Nicaragua's proposed canal had been approved. The construction work began in December 2014 and is projected by HKND to take 5 years.[124] The Nicaraguan parliament approved plans for the 173-mile canal through Nicaragua. According to the deal, the company will be responsible for operating and maintaining the canal for a 50-year period. The government of Nicaragua hopes this will boost the economy; the opposition is concerned with its environmental impact. Hundreds of thousands of local residents will be displaced by the canal and nearly a million acres of delicate ecosystems will be destroyed by the time construction is completed in early 2019.[125][126]

Other projects

Individuals, companies, and governments have explored the possibility of constructing deep water ports and rail links connecting coasts as a "dry canal" in Guatemala, Costa Rica, and El Salvador/Honduras. However, plans to construct these sea-rail-sea links have yet to materialize.[127]

Panama Canal Honorary Pilots

During the last one hundred years, the Panama Canal Authority has appointed a few "Panama Canal Honorary Pilots." The most recent of these were Commodore Ronald Warwick,[128] a former Master of the Cunard Liners RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 and RMS Queen Mary 2, who has traversed the Canal more than 50 times, and Captain Raffaele Minotauro, an Unlimited Master Senior Grade, of the former Italian governmental navigation company known as the "Italian Line."

See also

- Canal Zone Police

- Cargo ship sizes

- Isthmus of Tehuantepec

- List of waterways

- Marion Power Shovel Company

- Nicaragua Canal

- Strait of Magellan

- Suez Canal

References

- 1 2 3 The Associated Press (2016-06-26). "Panama Canal Opens $5B Locks, Bullish Despite Shipping Woes". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- ↑ "Panama Canal Traffic—Years 1914–2010". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ "Seven Wonders". American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ "A History of the Panama Canal: French and American Construction Efforts". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 2007-09-03.; Chapter 3, Some Early Canal Plans

- ↑ James Rodger Fleming (1990). Meteorology in America, 1800–1870. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0801839580.

- ↑ Caso, Adolph; Marion E. Welsh (1978). They Too Made America Great. Branden Books. p. 72. ISBN 0-8283-1714-3.;online at Google Books

- ↑ "Darien Expedition". Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1843-08-24/ed-1/seq-/#date1=1836&index=1&rows=20&words=Lexington+Ship+ship&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=New+York&date2=1850&proxtext=lexington+ship&y=10&x=16&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1)

- ↑ "Manx Worthies"

- ↑ The Practicality and Importance of a Ship Canal to Connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

- ↑ Gérard Fauconnier Panama: Armand Reclus et le canal des deux océans e-text University of Virginia reprint in French Panama Atlantica 2004

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 125.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 103–123.

- ↑ Cadbury, Deborah (2003). Seven Wonders of the Industrial World. London and New York: Fourth Estate. pp. 252–260.

- 1 2 3 Avery, Ralph E. (1913). "The French Failure". America's Triumph in Panama. Chicago, IL: L.W. Walter Company.

- ↑ Rocco, Fiammetta (2003). The Miraculous Fever-Tree. HarperCollins. p. 192. ISBN 0-00-653235-7.

- ↑ "The Panama Canal: Explorers, pirates, scientists and engineers – University of Michigan News". umich.edu.

- ↑ "Read our history: The French Canal Construction". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Cadbury 2003, p. 262.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 224.

- ↑ Cadbury 2003, p. 261.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 305–328.

- ↑ "Hay-Herrán Treaty". U-s-history.com. 1903-11-18. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ↑ Livingstone, Grace (2009). America's backyard : the United States and Latin America from the Monroe Doctrine to the war on terror. London: Zed. p. 13. ISBN 9781848132146.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 361–386.

- ↑ "Avalon Project—Convention for the Construction of a Ship Canal (Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty), November 18, 1903". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ↑ "September 07, 1977 : Panama to control canal". History.com. 2010. Retrieved Apr 4, 2015.

- ↑ Lowe, Vaughan. International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 66. Retrieved Apr 4, 2015.

- ↑ Hanson, David C. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal" (PDF). Virginia Western Community College. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ The Panama Canal Congressional Hearings 1909; Col. Goethals testimony; p.15 Accessed 26 December 2011

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 273–274.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 440.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 457.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 459–462.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 405–426.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 466–468.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 485–489.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 503–508.

- ↑ Brodhead, Michael J. 2012. "The Panama Canal: Writings of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Officers Who Conceived and Built It." Page 1.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 540–542.

- ↑ David Du Bose Gaillard Accessed 12 January 2012

- ↑ "Wilson blows up last big barrier in Panama Canal". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. 1913-10-11. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 607.

- ↑ McCullough 1977, pp. 609.

- ↑ CPI calculator Accessed 5 January 2012

- ↑ "Read our history: American Canal Construction". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ John Lawrence, Rector (2005), The History of Chile, pp. xxvi

- ↑ Martinic Beros, Mateo (2001), "La actividad industrial en Magallanes entre 1890 y mediados del siglo XX.", Historia, 34

- ↑ Figueroa, Victor; Gayoso, Jorge; Oyarzun, Edgardo; Planas, Lenia. "Investigación aplicada sobre Geografía Urbana: Un caso práctico en la ciudad de Valdivia". Gestion Turistica, UACh.

- ↑ "Panama Dam to Aid Canal Traffic." Popular Mechanics, January 1930, p. 25.

- ↑ "Enlarging the Panama Canal". czbrats.com.

- ↑ "Presentation on the Third Locks Project – Panama Canal Zone". czimages.com.

- ↑ The Martyrs of 1964, by Eric Jackson

- 1 2 "Hydroelectric Plants in Panama". 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- 1 2 "Panama Canal Traffic—Fiscal Years 2002–2004" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ "Historical Map & Chart Project". NOAA. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Zaret, Thomas M.; Paine, R.T. (2 November 1973). "Species Introduction in a Tropical Lake". Science. 182 (4111): 449–455. Bibcode:1973Sci...182..449Z. doi:10.1126/science.182.4111.449. PMID 17832455.

- ↑ "Peacock Bass: Fun to Catch, Fine to Eat". Panama Canal Review. February 1971: 11. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ "Gatun Lake Peacock Bass Fishing Charters". Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ Modern ship size definitions, from Lloyd's register

- ↑ Background of the Panama Canal, Montclair State University

- ↑ "The Panama Canal". Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "New Panamax publication by ACP" (PDF). November 2006. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ↑ "Marine Tariff". Panama Canal Authority.

- ↑ Panama Canal Toll Table http://www.pancanal.com/eng/op/tariff/1010-0000-Rev20160414.pdf

- ↑ "US Today Travel: Panama Canal Facts". USA Today. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ↑ "ACP rectifica récord en pago de peaje" (in Spanish). La Prensa. 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ "Récord en pago de peajes y reserva". La Prensa Sección Economía & Negocios Edition. Ediciones.prensa.com. 2007-04-24. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ↑ "Cupo de subasta del Canal alcanza récord. La Prensa. Sección Economía & Negocios. Edición 25 August 2006 in Spanish". Mensual.prensa.com. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ↑ "About ACP - PanCanal.com". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Cullen, Bob (March 2004). "Panama Rises". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ "ACP 2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2005. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ "News—PanCanal.com; Panama Canal Authority Announces Fiscal Year 2008 Metrics". Panama Canal Authority. 2008-10-24. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ "News—PanCanal.com; Panama Canal Authority Announces Fiscal Year 2009 Metrics". Panama Canal Authority. 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Lipton, Eric (2004-11-22). "New York Port Hums Again, With Asian Trade". New York Times.

- 1 2 "ACP 2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ "Panama Canal Traffic—Fiscal Years 2013 through 2015" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority.

- ↑ Nettleton, Steve (1999). "Transfer heavy on symbolism, light on change". CNN Interactive. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008.

- ↑ "9 Facts about the Panama Canal Expansion – Infographic". Mercatrade. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News—Panama Canal reopens after temporary closure". 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ "The Press Association: Panama flooding displaces thousands". 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "NOTICIAS PANAMÁ—PERIODICO LA ESTRELLA ONLINE: Gobierno abrirá parcialmente Puente Centenario; Corredores serán gratis [Al Minuto]". 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ "Rain Causes Panama Canal Bridge To Collapse". digtriad.com. 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ↑ "Entrance to Panama Canal Bridge Closed due to Rain Damage". 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ "Aftermath of Panama flooding hits transport and finances—rain continues". 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Mack, Gerstle (1944). The Land Divided—A History of the Panama Canal and other Isthmian Canal Projects.

- ↑ Proposal for the Expansion of the Panama Canal Panama Canal Authority, p. 45

- ↑ Jackson, Eric (2007). Shipping industry complains about PanCanal toll hikes.

- ↑ "Maersk Line to Dump Panama Canal for Suez as Ships Get Bigger". 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ De Cordoba, Jose (June 13, 2013). "Nicaragua Revives Its Canal Dream". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Sevunts, Levon (2005-06-12). "Northwest Passage redux". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2009-04-20. See also: Comte, Michel (2005-12-22). "Conservative Leader Harper Asserts Canada's Arctic Claims". DefenceNews.com (Agence France-Presse). Retrieved 2006-02-23.

- ↑ "The Panama Canal; Canal FAQ". Archived from the original on 2010-09-15.

- ↑ "The Panama Canal—Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on May 7, 2009.

Each lock chamber requires 101,000 m3 (26,700,000 US gal; 22,200,000 imp gal) of water. An average of 200,000,000 L (52,000,000 US gal) of fresh water are used [in a single passing].

- ↑ "Sea Level: Frequently Asked Questions and Answers", psmsl.org

- 1 2 "Relevant Information on the Third Set of Locks Project" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2006-04-24. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- ↑ "The Panama Canal". Business in Panama. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Monahan, Jane (2006-04-04). "Panama Canal set for $7.5bn revamp". BBC News.

- ↑ "Panama Canal Authority: Panama Canal Expansion is "2009 Project Finance Deal of the Year", 12 March 2010". Pancanal.com. 2010-03-12. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ↑ "Panama approves $5.25 billion canal expansion". MSNBC.com. 2006-10-22.

- ↑ Reagan, Brad (February 2007). "The Panama Canal's Ultimate Upgrade". Popular Mechanics.

- ↑ Kaufman, Andrew (February 2010). "The Panama Canal Gets a New Lane". Popular Mechanics.

- ↑ "Work starts on biggest-ever Panama Canal overhaul". Reuters. 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (19 June 2012). "Panama Canal Completes First Monolith at the New Pacific Locks". Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ Ship and Bunker (2 July 2012). "Delay Confirmed on Panama Canal Expansion Project". Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ↑ Dredging News Online (29 August 2014). "Panama Canal Authority updates Maersk Line on expansion programme". Dredging News Online. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ↑ Dredging News Online (1 September 2014). "Panama Canal Authority updates Maersk Line on expansion programme". Hellenic Shipping News. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (20 August 2014). "Panama Canal Updates Maersk Line on Expansion Program". Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Bruce (9 Sep 2014). "Maritime panel to hold sessions on port congestion". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 11 Sep 2014.

- ↑ "De Nul dredging company to build locks in Panama Canal". Flanders Today. 2009-07-17.

- ↑ "Contract dispute jeopardizes Panama Canal schedule". American Shipper. January 2, 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Lomi Kriel; Elida Moreno (January 8, 2014). "Panama Canal refuses to pay $1 billion more for expansion work". Reuters. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (20 February 2014). "Panama Canal New Locks Project Works Resume". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (10 June 2014). "Second Shipment of new gates arrive at the Panama Canal". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (11 June 2015). "Panama Canal Expansion Begins Filling of New Locks". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Stone, Kathryn (10 June 2015). "Flooding of Expanded Panama Canal Begins". The Maritime Executive.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (22 June 2015). "Panama Canal Expansion Moves Ahead with Filling of New Pacific Locks". Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority (23 March 2016). "Panama Canal Inaugurates Scale Model Training Facility, Announces Expansion Inauguration Date". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ WALT BOGDANICH, JACQUELINE WILLIAMS and ANA GRACIELA MÉNDEZ (JUNE 22, 2016) The New Panama Canal: A Risky Bet The New York Times, Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ John Paul Rathbone, Naomi Mapstone (2011-02-13). "China in talks over Panama Canal rival". Financial Times. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ Wheatley, Jonathan (2011-02-14). "Colombia's smart canal". Financial Times. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "China in talk with Columbia over transcontinental railway: Colombian president". Xinhuanet. 2011-02-14. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ Branigan, Tania and Lin Yi. China goes on the rails to rival Panama canal The Guardian, 14 February 2011. Accessed: 14 February 2011.

- ↑ "Nicaragua launches construction of inter-oceanic canal". BBC. December 23, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ↑ "A Chinese company wants to build a new canal in America (news in Estonian)". Postimees. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Shaer, Matthew. "A New Canal Through Central America Could Have Devastating Consequences". smithsonianmag.com.

- ↑ Van Marle, Gavin (July 2013). "Canal mania hits central America with three more Atlantic-Pacific projects". The Load Star.

- ↑ "Buckingham First Day Covers". Internet Stamps Group Limited. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

Further reading

Construction and technical issues

- Brodhead, Michael J. 2012. "The Panama Canal: Writings of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Officers Who Conceived and Built It." US Army Corps of Engineers History Office, Alexandria, VA.

- Hoffman, Jon T.; Brodhead, Michael J; Byerly, Carol R.; Williams, Glenn F. (2009). The Panama Canal: An Army's Enterprise. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. 70–115–1.

- Jaen, Omar. (2005). Las Negociaciones de los Tratados Torrijos-Carter, 1970–1979 (Tomos 1 y 2). Panama: Autoridad del Canal de Panama. ISBN 9962-607-32-9 (Obra completa)

- Jorden, William J. (1984). Panama Odyssey. 746 pages, illustrated. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-76469-3

- McCullough, David (1977), The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-24409-4

- Mills, J. Saxon. (1913). The Panama Canal—A history and description of the enterprise A Project Gutenberg free ebook.

- Parker, Matthew. (2007). Panama Fever: The Epic Story of One of the Greatest Human Achievements of All Time—The Building of the Panama Canal. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51534-4

- Sherman, Gary. "Conquering the Landscape (Gary Sherman explores the life of the great American trailblazer, John Frank Stevens)," History Magazine, July 2008.

Diplomatic and political history

- Gilboa, Eytan. "The Panama Invasion Revisited: Lessons for the Use of Force in the Post Cold War Era." Political Science Quarterly (1995): 539–562. in JSTOR

- Greene, Julie, The Canal Builders: Making America's Empire at the Panama Canal (New York: Penguin Press, 2009)

- Hogan, J. Michael. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Heroes of Panama." Presidential Studies Quarterly 19 (1989): 79-94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40574566

- LaFeber, Walter. The Panama Canal: the crisis in historical perspective (Oxford University Press, 1978)

- Major, John. Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal, 1903–1979 (1993)

- Maurer, Noel, and Carlos Yu. The Big Ditch: How America Took, Ran, and Ultimately Gave Away the Panama Canal (Princeton University Press, 2010); 420 pp. ISBN 978-0-691-14738-3. Econometric analysis of costs ($9 billion in 2009 dollars) and benefits to US and Panama

- Mellander, Gustavo A.(1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Daville,Ill.:Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

- Sánchez, Peter M. Panama Lost? US Hegemony, Democracy and the Canal (University Press of Florida, 2007), 251 pp,

- Sánchez, Peter M. "The end of hegemony? Panama and the United States." International Journal on World Peace (2002): 57–89. in JSTOR

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Panama Canal Authority website—Has a simulation showing how the canal works

- Making the Dirt Fly, Building the Panama Canal Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Canalmuseum—History, Documents, Photographs and Stories

- Early stereographic images of the construction University of California

- A.B. Nichols Panama Canal Collection at the Linda Hall Library Archival collection of maps, blueprints, photographs, letters, and other documents, collected by Aurin B. Nichols, an engineer who worked on the canal project through from 1899 until its completion.

Coordinates: 9°04′48″N 79°40′48″W / 9.08000°N 79.68000°W