Anti-Christian policies in the Roman Empire

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Anti-Christian policies in the Roman Empire occurred intermittently over a period of over two centuries until the year 313AD when the Roman Emperors Constantine the Great and Licinius jointly promulgated the Edict of Milan which legalised the Christian religion. The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire was carried out by the state and also by local authorities on a sporadic, ad hoc basis, often at the whims of local communities. Starting in 250, empire-wide persecution took place by decree of the emperor Decius. The edict was in force for eighteen months, during which time some Christians were killed while others betrayed their faith to escape execution.

These persecutions heavily influenced the development of Christianity, shaping Christian theology and the structure of the Church. Among other things, persecution gave rise to many saints' cults which may have contributed to the rapid spread of Christianity and sparked written explanations and defenses of the Christian religion.

Duration and extent

Anti-Christian policies directed at the early church had occurred sporadically and in localised areas since its beginning. The first persecution of Christians organised by the Roman government took place under the emperor Nero in 64 AD after the Great Fire of Rome. With the passage in 313 AD of the Edict of Milan, anti-Christian policies directed against Christians by the Roman government ceased.[1] The total number of Christians who lost their lives because of these persecutions is unknown; although early church historian Eusebius, whose works are the only source for many of these events, speaks of "great multitudes" having perished, he is thought by many scholars today to have exaggerated their numbers.[1][2]:217–233

There was no empire-wide persecution of Christians until the reign of Decius in the third century.[3] Provincial governors had a great deal of personal discretion in their jurisdictions and could choose themselves how to deal with local incidents of persecution and mob violence against Christians. For most of the first three hundred years of Christian history, Christians were able to live in peace, practice their professions, and rise to positions of responsibility. Only for approximately ten out of the first three hundred years of the church's history were Christians executed due to orders from a Roman emperor.[2]:129

Reasons

Public interest

Without agitation from the public, the Roman government had little motivation to persecute local Christians. However, because of the secrecy of their rituals, Christians frequently aroused suspicion among the pagan population accustomed to religion as a public event; beliefs developed that Christians committed flagitia, scelera, and maleficia— "outrageous crimes", "wickedness", and "evil deeds", specifically, cannibalism and incest (referred to as "Thyestian banquets" and "Oedipodean intercourse")— due to their rumored practices of eating the "blood and body" of Christ and referring to each other as "brothers" and "sisters".[4][5] Christians' refusal to participate in public religion was as problematic to the populace as it was to the elites, and contributed to the general hostility toward Christians. Much of the pagan populace maintained a sense that bad things would happen if the established pagan gods were not respected and worshiped properly.[6][7] Edward Gibbon wrote:

"By embracing the faith of the Gospel the Christians incurred the supposed guilt of an unnatural and unpardonable offence. They dissolved the sacred ties of custom and education, violated the religious institutions of their country, and presumptuously despised whatever their fathers had believed as true, or had reverenced as sacred."[8]

Gibbon argued that the seeming tendency of Christian converts to renounce their family and country, their dislike for the common business and pleasures of life, and their frequent predictions of impending disasters instilled a feeling of apprehension in their pagan neighbours.[9] As Christianity became more widespread and better understood, however, these suspicions faded away.[10]

Legal basis

Due to the informal and personality-driven nature of the Roman legal system, nothing "other than a prosecutor" (an accuser, including a member of the public, not only a holder of an official position), "a charge of Christianity, and a governor willing to punish on that charge"[11] was required to bring a legal case against a Christian. Roman law was largely concerned with property rights, leaving many gaps in criminal and public law. Thus the process cognitio extra ordinem ("special investigation") filled the legal void left by both code and court. All provincial governors had the right to run trials in this way as part of their imperium in the province.[12]

In cognitio extra ordinem, an accuser called a delator brought before the governor an individual to be charged with a certain offense—in this case, that of being a Christian. This delator was prepared to act as the prosecutor for the trial, and could be rewarded with some of the accused's property if he made an adequate case or charged with calumnia (malicious prosecution) if his case was insufficient. If the governor agreed to hear the case—and he was free not to—he oversaw the trial from start to finish: he heard the arguments, decided on the verdict, and passed the sentence.[13] Christians sometimes offered themselves up for punishment, and the hearings of such voluntary martyrs were conducted in the same way.

More often than not, the outcome of the case was wholly subject to the governor's personal opinion. While some tried to rely on precedent or imperial opinion where they could, as evidenced by Pliny the Younger's letter to Trajan concerning the Christians,[14] such guidance was often unavailable.[15] In many cases months' and weeks' travel away from Rome, these governors had to make decisions about running their provinces according to their own instincts and knowledge.

Even if these governors had easy access to the city, they would not have found much official legal guidance on the matter of the Christians. Before the anti-Christian policies under Decius beginning in 250, there was no empire-wide edict against the Christians, and the only solid precedent was that set by Trajan in his reply to Pliny: the name of "Christian" alone was sufficient grounds for punishment and Christians were not to be sought out by the government. There is speculation that Christians were also condemned for contumacia—disobedience toward the magistrate, akin to the modern "contempt of court"—but the evidence on this matter is mixed.[16] Melito of Sardis later asserted that Antoninus Pius ordered that Christians were not to be executed without proper trial.[17]

Given the lack of guidance and distance of imperial supervision, the outcomes of the trials of Christians varied widely. Many followed Pliny's formula: they asked if the accused individuals were Christians, gave those who answered in the affirmative a chance to recant, and offered those who denied or recanted a chance to prove their sincerity by making a sacrifice to the Roman gods and swearing by the emperor's genius. Those who persisted were executed.

According to the Christian apologist Tertullian, some governors in Africa helped accused Christians secure acquittals or refused to bring them to trial.[18] Overall, Roman governors were more interested in making apostates than martyrs: one proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, when confronted with a group of voluntary martyrs during one of his assize tours, sent a few to be executed and snapped at the rest, "If you want to die, you wretches, you can use ropes or precipices."[19]

During the Great Persecution which lasted from 303 to 312/313, governors were given direct edicts from the emperor. Christian churches and texts were to be destroyed, meeting for Christian worship was forbidden, and those Christians who refused to recant lost their legal rights. Later, it was ordered that Christian clergy be arrested and that all inhabitants of the empire sacrifice to the gods. Still, no specific punishment was prescribed by these edicts and governors retained the leeway afforded to them by distance.[20] Lactantius reported that some governors claimed to have shed no Christian blood,[10] and there is evidence that others turned a blind eye to evasions of the edict or only enforced it when absolutely necessary. When an imperial edict ordering clemency to jailed Christians was eventually issued, governors eagerly cleared their overcrowded jails.

Government motivation

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

|

| Related topics |

When a governor was sent to a province, he was charged with the task of keeping it pacata atque quieta—settled and orderly.[21] His primary interest would be to keep the populace happy; thus when unrest against the Christians arose in his jurisdiction, he would be inclined to placate it with appeasement lest the populace "vent itself in riots and lynching."[22]

Political leaders in the Roman Empire were also public cult leaders. Roman religion revolved around public ceremonies and sacrifices; personal belief was not as central an element as it is in many modern faiths. Thus while the private beliefs of Christians may have been largely immaterial to many Roman elites, this public religious practice was in their estimation critical to the social and political well-being of both the local community and the empire as a whole. Honoring tradition in the right way — pietas — was key to stability and success.[23] Hence the Romans protected the integrity of cults practiced by communities under their rule, seeing it as inherently correct to honor one's ancestral traditions; for this reason the Romans for a long time tolerated the highly exclusive Jewish sect, even though some Romans despised it.[24] Historian H. H. Ben-Sasson has proposed that the "Crisis under Caligula" (37-41) was the "first open break" between Rome and the Jews.[25] After the First Jewish–Roman War (66-73), Jews were officially allowed to practice their religion as long as they paid the Jewish tax. There is debate among historians over whether the Roman government simply saw Christians as a sect of Judaism prior to Nerva's modification of the tax in 96. From then on, practicing Jews paid the tax while Christians did not, providing hard evidence of an official distinction.[26] Part of the Roman disdain for Christianity, then, arose in large part from the sense that it was bad for society. In the 3rd century, the Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry wrote:

"How can people not be in every way impious and atheistic who have apostatized from the customs of our ancestors through which every nation and city is sustained? ... What else are they than fighters against God?"[27]

Once distinguished from Judaism, Christianity was no longer seen as simply a bizarre sect of an old and venerable religion; it was a superstitio.[24] Superstition had for the Romans a much more powerful and dangerous connotation than it does for much of the Western world today: to them, this term meant a set of religious practices that were not only different, but corrosive to society, "disturbing a man's mind in such a way that he is really going insane" and causing him to lose humanitas (humanity).[28] The persecution of "superstitious" sects was hardly unheard-of in Roman history: an unnamed foreign cult was persecuted during a drought in 428 BCE, some initiates of the Bacchic cult were executed when deemed out-of-hand in 186 BCE, and measures were taken against the Druids during the early Principate.[29]

Even so, the level of persecution experienced by any given community of Christians still depended upon how threatening the local official deemed this new superstitio to be. Christians' beliefs would not have endeared them to many government officials: they worshipped a convicted criminal, refused to swear by the emperor's genius, harshly criticized Rome in their holy books, and suspiciously conducted their rites in private. In the early third century one magistrate told Christians "I cannot bring myself so much as to listen to people who speak ill of the Roman way of religion."[30]

History

Overview

By the mid-2nd century, mobs were willing to throw stones at Christians, and they might be mobilized by rival sects. The Persecution in Lyon was preceded by mob violence, including assaults, robberies and stonings.[31] Lucian tells of an elaborate and successful hoax perpetrated by a "prophet" of Asclepius, using a tame snake, in Pontus and Paphlygonia. When rumor seemed about to expose his fraud, the witty essayist reports in his scathing essay

... he issued a promulgation designed to scare them, saying that Pontus was full of atheists and Christians who had the hardihood to utter the vilest abuse of him; these he bade them drive away with stones if they wanted to have the god gracious.

Tertullian's Apologeticus of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and addressed to Roman governors.[32]

Prior to 64 AD, there is no evidence for action taken by the Roman government against Christians, and after that episode under Nero, no further evidence for anti-Christian policies against Christians until 250 AD. In 250 AD, the emperor Decius issued a decree requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the emperor and the established order. There is no evidence that the decree was intended to target Christians but was intended as a form of loyalty oath. Decius authorized roving commissions visiting the cities and villages to supervise the execution of the sacrifices and to deliver written certificates to all citizens who performed them. Christians were often given opportunities to avoid further punishment by publicly offering sacrifices or burning incense to Roman gods, and were accused by the Romans of impiety when they refused. Refusal was punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture, and executions. Christians fled to safe havens in the countryside and some purchased their certificates, called libelli. Several councils held at Carthage debated the extent to which the community should accept these lapsed Christians.

The persecutions culminated with Diocletian and Galerius at the end of the third and beginning of the 4th century. Their anti-Christian actions, considered the largest, was to be the last major Roman Pagan action, as Constantine the Great soon came into power and in 313 legalized Christianity. It was not until Theodosius I in the latter 4th century, however, that Christianity would become the official religion of the Roman Empire.

64-250

Prior to Nero's accusation of arson and subsequent anti-Christian actions in 64, all animosity was apparently limited to intramural Jewish hostility. In the New Testament (Acts 18:2-3), a Jew named Aquila is introduced who, with his wife Priscilla, had recently come from Italy because emperor Claudius "had ordered all the Jews to leave Rome". It is generally agreed that from Nero's reign until Decius's widespread measures in 250, the Anti-Christian policies by Romans were limited to isolated, local incidents.[33] Although it is often claimed that Christians were persecuted for their refusal to worship the emperor, general dislike for Christians likely arose from their refusal to worship the gods or take part in sacrifice, which was expected of those living in the Roman Empire.[33] Although the Jews also refused to partake in these actions, they were tolerated because they followed their own Jewish ceremonial law, and their religion was legitimized by its ancestral nature.[34] On the other hand, they believed Christians, who were believed to take part in strange rituals and nocturnal rites, cultivated a dangerous and superstitious sect.[35]

During this period, Anti-Christian activities were accusatory and not inquisitive.[33] Governors played a larger role in the actions than did Emperors, but Christians were not sought out by governors, and instead accused and prosecuted through a process termed cognitio extra ordinem. No reliable, extant description of a Christian trial exists, but evidence shows that trials and punishments varied greatly, and sentences ranged from acquittal to death.[36]

Nero

Evidence from ancient documents suggests that the anti-Christian policies by the Roman government did not occur until the reign of Nero.[33] In 64, a great fire broke out in Rome, destroying portions of the city and economically devastating the Roman population. Tacitus records (Annals 15.44) that Nero was rumored to have ordered the fire himself, and in order to dispel the accusations, accused and savagely punished the already-detested Christians. Suetonius mentions that Christians were killed under Nero's reign, but does not mention anything about the fire (Nero 16.2)[37] Scholars disagree about whether Christians were persecuted solely under the charge of organized arson or for other general crimes associated with Christianity.[33][38]

Because Tertullian mentions an institutum Neronianum in his apology "To the Nations", scholars also debate the possibility of a creation of a law or decree against the Christians under Nero. However, it has been argued that in context, the institutum Neronianum merely describes the anti-Christian activities; it does not provide a legal basis for them. Furthermore, no known writers show knowledge of a law against Christians.[39]

Domitian

According to some historians, Jews and Christians were heavily persecuted toward the end of Domitian's reign (89-96).[40] The Book of Revelation, which mentions at least one instance of martyrdom (Rev 2:13; cf. 6:9), is thought by many scholars to have been written during Domitian's reign.[41] Early church historian Eusebius wrote that the social conflict described by Revelation reflects Domitian's organization of excessive and cruel banishments and executions of Christians, but these claims may be exaggerated or false.[42] Some historians, however, have maintained that there was little or no anti-Christian activitity during Domitian's time.[43][44][45] The lack of consensus by historians about the extent of persecution during the reign of Domitian derives from the fact that while accounts of persecution exist, these accounts are very cursory or their reliability is debated.[38]

Often, reference is made to the execution of Flavius Clemens, a Roman consul and cousin of the Emperor, and the banishment of his wife, Flavia Domitilla, to the island of Pandateria. Eusebius wrote that Flavia Domitilla was banished because she was a Christian. However, in Cassius Dio's account (67.14.1-2), he only reports that she, along with many others, was guilty of sympathy for Judaism.[46] Suetonius does not mention the exile at all.[47] According to Keresztes, it is more probable that they were converts to Judaism who attempted to evade payment of the Fiscus Judaicus - the tax imposed on all persons who practiced Judaism. (262-265).[41] In any case, no stories of anti-Christian activities during Domitian's reign reference any sort of legal ordinances[38]

Trajan

Between 109 and 111, Pliny the Younger was sent by the emperor Trajan (r. 98-117) to the province of Bithynia (in Anatolia) as governor, and their correspondence is considered a valuable historical source. In one of his letters (Letter 10.96), Pliny reports on his actions with regard to some people who had been denounced as Christians, some of them anonymously: those that persisted in confessing that they were Christians he had executed or, if Roman citizens, sent to Rome; those who denied that they were Christians he subjected to the test of invoking the gods, offering them incense and a libation in the presence of an image of the emperor, and cursing Christ. Some who admitted that they had formerly been Christians but proved, by passing the test, that they were such no longer declared that Christians did not commit the crimes attributed to them, a declaration confirmed under torture by two slave women who were called deaconesses. Pliny therefore asked the emperor whether ceasing to be a Christian was enough to secure pardon for having been one, and whether punishment was merited just for being a Christian ("the name itself") or only for the crimes associated with the name. Trajan responded that the problem could only be dealt with case by case. The authorities were not to seek Christians out, but people who were denounced and found guilty were to be punished unless, by worshipping the Roman gods, they proved they were not Christians (having denied Christ) and so obtained pardon. Anonymous denunciations were to be ignored.[48][49][50][51]

Hadrian

The emperor Hadrian, reigned 117 - 138, also responding to a request for advice from a provincial governor about how to deal with Christians, granted Christians more leniency. Hadrian stated that merely being a Christian was not enough for action against them to be taken, they must also have committed some illegal act. In addition, "slanderous attacks" against Christians were not to be tolerated, meaning that anyone who brought an action against Christians but failed would face punishment themselves. This order of Hadrian was attached by Christian apologist Justin Martyr to the end of his First Apology, c. 155.[52]

Marcus Aurelius to Maximinus the Thracian

Sporadic bouts of anti-Christian activity occurred during the period from the reign of Marcus Aurelius to that of Maximinus. Governors continued to play a more important role than emperors in persecutions during this period.[53]

In the first half of the third century, the relation of Imperial policy and ground-level actions against Christians remained much the same:

It was pressure from below, rather than imperial initiative, that gave rise to troubles, breaching the generally prevailing but nevertheless fragile, limits of Roman tolerance: the official attitude was passive until activated to confront particular cases and this activation normally was confined to the local and provincial level.[54]

Apostasy in the form of symbolic sacrifice continued to be enough to set a Christian free.[53] It was standard practice to imprison a Christian after an initial trial, with pressure and an opportunity to recant.[55]

The number and severity of persecutions in various locations of the empire seemingly increased during the reign of Marcus Aurelius,161-180. The extent to which Marcus Aurelius himself directed, encouraged, or was aware of these persecutions is unclear and much debated by historians.[56] One of the most notable instances of persecution during the reign of Aurelius occurred in 177 at Lugdunum (present-day Lyons, France), where the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls had been established by Augustus in the late 1st century BC. The sole account is preserved by Eusebius. The persecution in Lyons started as an unofficial movement to ostracize Christians from public spaces such as the market and the baths, but eventually resulted in official action. Christians were arrested, tried in the forum, and subsequently imprisoned.[57] They were condemned to various punishments: being fed to the beasts, torture, and the poor living conditions of imprisonment. Slaves belonging to Christians testified that their masters participated in incest and cannibalism. Barnes cites this persecution as the "one example of suspected Christians being punished even after apostasy.".[53]

A number of persecutions of Christians occurred in the Roman empire during the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211).The traditional view has been that Severus was responsible. This is based on a reference to a decree he is said to have issued forbidding conversions to Judaism and Christianity but this decree is known only from one source, the Augustan History, an unreliable mix of fact and fiction.[58]:184 Early church historian Eusebius describes Severus as a persecutor, but the Christian apologist Tertullian states that Severus was well disposed towards Christians, employed a Christian as his personal physician and had personally intervened to save several high-born Christians known to him from "the mob".[58]:184 Eusebius' description of Severus as a persecutor likely derives merely from the fact that numerous persecutions occurred during his reign,including those known in the Roman martyrology as the martyrs of Madaura and Perpetua and Felicity in the Roman province of Africa, but these were probably as the result of local persecutions rather than empire wide actions or decrees by Severus.[58]:185

Other instances of persecution occurred before the reign of Decius, but there are fewer accounts of them from 215 onward. This may reflect a decrease in hostility toward Christianity, or gaps in the available sources.[53] Perhaps the most famous of these post-Severan persecutions are those attributed to Maximinus the Thracian, reigned 235-238. According to Eusebius, a persecution undertaken by Maximinus against heads of the church in 235 sent both Hippolytus and Pope Pontian into exile on Sardinia. Other evidence suggests the persecution of 235 was local to Cappadocia and Pontus, and not set in motion by the emperor.[59]

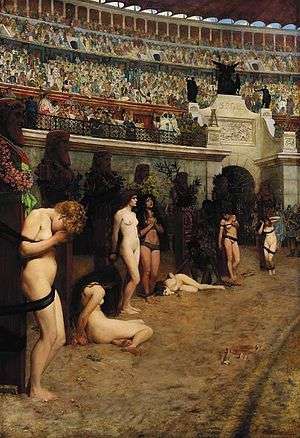

Punishments

Christians who refused to recant by performing ceremonies to honour the gods would meet with severe penalties; Roman citizens were exiled or condemned to a swift death by beheading. Slaves, foreign-born residents and lower classes were liable to be put to death by wild beasts as a public spectacle.[60] A variety of animals were used for those condemned to die in this way. There is no evidence of Christians being executed at the Colosseum in Rome.[61]

Decius

In 250, the emperor Decius issued an edict, the text of which has been lost, requiring everyone in the Empire (except Jews, who were exempted) to perform a sacrifice to the gods in the presence of a Roman magistrate and obtain a signed and witnessed certificate, called a libellus, to this effect.[62] The decree was part of Decius' drive to restore traditional Roman values and there is no evidence that Christians were specifically being targeted.[63] A number of these certificates still exist, one discovered in Egypt, in one person's handwriting, (Text of papyrus in illustration) reads:[64]

To those in charge of the sacrifices of the village Theadelphia, from Aurelia Bellias, daughter of Peteres, and her daughter Kapinis. We have always been constant in sacrificing to the gods, and now too, in your presence, in accordance with the regulations, I have poured libations and sacrificed and tasted the offerings, and I ask you to certify this for us below. May you continue to prosper. (Second person's handwriting) We, Aurelius Serenus and Aurelius Hermas, saw you sacrificing. (Third person's handwriting) I, Hermas, certify. The first year of the Emperor Caesar Gaius Messias Quintus Traianus Decius Pius Felix Augustus, Pauni 27.

When the provincial governor Pliny had written to the emperor Trajan in 112, he said he required suspected Christians to curse Christ, but there is no mention of Christ or Christians in the certificates from Decius' reign.[65] Nevertheless, this was the first time that Christians throughout the Empire had been forced by imperial edict to choose between their religion and their lives[2] and a number of prominent Christians, including Pope Fabian, Babylas of Antioch and Alexander of Jerusalem died as a result of their refusal to perform the sacrifices.[62] The number of Christians who were executed as a result of their refusal to obtain a certificate is not known, nor how much of an effort was made by the authorities to check who had received a certificate and who had not, but it is known that large numbers of Christians apostatized and performed the ceremonies while others, including Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, went into hiding.[2] Although the period of enforcement of the edict was only about eighteen months, it was severely traumatic to many Christian communities which had until then lived undisturbed, and left bitter memories of monstrous tyranny.[66] The Decian persecution had lasting repercussions for the church. How should those who had obtained a certificate or actually sacrificed be treated? It seems that in most churches, those who had lapsed were accepted back into the fold, but some groups refused them admission to the church. This raised important issues about the nature of the church, forgiveness, and the high value of martyrdom. A century and a half later, St. Augustine would battle with an influential group called the Donatists, who broke away from the Catholic Church because the latter embraced the lapsed.

Valerian

The emperor Valerian took the throne in 253 but from the following year he was away from Rome fighting the Persians who had conquered Antioch, and he never returned, as he was taken captive and died a prisoner. However he sent two letters regarding Christians to the Senate. The first, in 257, ordered all Christian clergy to perform sacrifices to the Roman gods and forbade Christians from holding meetings in cemeteries.[67] A second letter the following year ordered that bishops and other high ranking church officials were to be put to death, and that senators and equites who were Christians were to be stripped of their titles and lose their property. If they would not perform sacrifices to the gods they also were to be executed. Roman matrons who would not apostatize were to lose their property and be banished, while civil servants and members of the Emperor's staff and household who refused to sacrifice would be reduced to slavery and sent to work on the Imperial estates.[68] The fact that there were such high ranking Christians at the very heart of the Roman imperial establishment shows both that the actions taken by Decius less than a decade before had not had a lasting effect and that Christians did not face constant persecution or hide from public view.[69]

Among those executed under Valerian were Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, and Sixtus II, Bishop of Rome with his deacons including Saint Lawrence. The public examination of Cyprian by the proconsul in Carthage, Galerius Maximus, on September 14, 258, has been preserved:[70]

Galerius Maximus:"Are you Thascius Cyprianus?" Cyprian: "I am." Galerius: "The most sacred Emperors have commanded you to conform to the Roman rites." Cyprian: "I refuse." Galerius: "Take heed for yourself." Cyprian: "Do as you are bid; in so clear a case I may not take heed." Galerius, after briefly conferring with his judicial council, with much reluctance pronounced the following sentence: "You have long lived an irreligious life, and have drawn together a number of men bound by an unlawful association, and professed yourself an open enemy to the gods and the religion of Rome; and the pious, most sacred and august Emperors ... have endeavoured in vain to bring you back to conformity with their religious observances; - whereas therefore you have been apprehended as principal and ringleader in these infamous crimes, you shall be made an example to those whom you have wickedly associated with you; the authority of law shall be ratified in your blood." He then read the sentence of the court from a written tablet: "It is the sentence of this court that Thascius Cyprianus be executed with the sword." Cyprian: "Thanks be to God."

Taken directly to the place of execution, Cyprian was decapitated. The words of the sentence show that in the eyes of the Roman state, Christianity was not a religion at all, and the church was a criminal organisation. When Valerian's son Gallienus became Emperor in 260, the legislation was revoked, and this brief period of persecution came to an end.

A warrant to arrest a Christian, dated 28 February 256, was found among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P. Oxy 3035). The grounds for the arrest are not given in the document.Valerian's first act as emperor on 22 October 253 was to make his son Gallienus his Caesar and colleague. Early in his reign, affairs in Europe went from bad to worse, and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal and Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor). Valerian and Gallienus split the problems of the empire between them, with the son taking the West, and the father heading East to face the Persian threat.

Diocletian and Galerius

Diocletian's accession in 284 did not mark an immediate reversal of disregard to Christianity, but it did herald a gradual shift in official attitudes toward religious minorities. In the first fifteen years of his rule, Diocletian purged the army of Christians, condemned Manicheans to death, and surrounded himself with public opponents of Christianity. Diocletian's preference for autocratic government, combined with his self-image as a restorer of past Roman glory, presaged the most pervasive persecution in Roman history. In the winter of 302, Galerius urged Diocletian to begin a general persecution of the Christians. Diocletian was wary, and asked the oracle of Apollo for guidance. The oracle's reply was read as an endorsement of Galerius's position, and a general persecution was called on February 24, 303.

Persecutory policies varied in intensity across the empire. Where Galerius and Diocletian were avid persecutors, Constantius was unenthusiastic. Later persecutory edicts, including the calls for all inhabitants to sacrifice to the Roman gods, were not applied in his domain. His son, Constantine, on taking the imperial office in 306, restored Christians to full legal equality and returned property that had been confiscated during the persecution. In Italy in 306, the usurper Maxentius ousted Maximian's successor Severus, promising full religious toleration. Galerius ended the persecution in the East in 311, but it was resumed in Egypt, Palestine, and Asia Minor by his successor, Maximinus. Constantine and Licinius, Severus's successor, signed the "Edict of Milan" in 313, which offered a more comprehensive acceptance of Christianity than Galerius's edict had provided. Licinius ousted Maximinus in 313, bringing an end to persecution in the East.

The persecution failed to check the rise of the church. By 324, Constantine was sole ruler of the empire, and Christianity had become his favored religion. Although the persecution resulted in death, torture, imprisonment, or dislocation for many Christians, the majority of the empire's Christians avoided punishment. The persecution did, however, cause many churches to split between those who had complied with imperial authority (the lapsi) and those who had held firm. Certain schisms, like those of the Donatists in North Africa and the Meletians in Egypt, persisted long after the persecutions: only after 411 would the Donatists be reconciled to the church to which in 380 Emperor Theodosius I reserved the title of "catholic". The cult of the martyrs in the centuries that followed the end of the persecutions gave rise to accounts that exaggerated the barbarity of that era. These accounts were criticized during the Enlightenment and after, most notably by Edward Gibbon. Modern historians like G. E. M. de Ste. Croix have attempted to determine whether Christian sources exaggerated the scope of the persecution by Diocletian.

Martyrdom

The earliest Christian martyrs, tortured and killed by Roman officials enforcing worship of the emperors, won so much fame among their co-religionists that others wished to imitate them to such an extent that a group presented themselves to the governor of Asia, declaring themselves to be Christians, and calling on him to do his duty and put them to death. He executed a few, but as the rest demanded it as well, he responded, exasperated, "You wretches, if you want to die, you have cliffs to leap from and ropes to hang by." This attitude was sufficiently widespread for Church authorities to begin to distinguish sharply "between solicited martyrdom and the more traditional kind that came as a result of persecution".[71] At a Spanish council held at the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries, the bishops denied the crown of martyrdom to those who died while attacking pagan temples. According to Ramsey MacMullen, the provocation was just "too blatant". Drake cites this as evidence that Christians resorted to violence, including physical, at times.[72]

Estimates for total martyred dead for the Great Persecution depend on the report of Eusebius of Caesarea in the Martyrs of Palestine. There are no other viable sources for the total number of martyrdoms in a province.[73] Ancient writers did not think statistically. When the size of a Christian population is described, whether by a pagan, Jewish, or Christian source, it is opinion or metaphor, not accurate reportage.[74]

During the Great Persecution, Eusebius was the bishop of Caesarea Maritima, the capital of Roman Palestine. Since, under Roman law, capital punishment could only be enforced by provincial governors, and because, most of the time, these governors would be in residence at the capital, most martyrdoms would take place within Eusebius' jurisdiction. When they did not, as when the provincial governor traveled to other cities to perform assizes, their activities would be publicized throughout the province. Thus, if Eusebius were an assiduous reporter of the persecutions in his province, he could easily have acquired a full tally of all martyred dead.[75]

Edward Gibbon, after lamenting the vagueness of Eusebius' phrasing, made the first estimate of martyr number as follows: by counting the total number of persons listed in the Martyrs, dividing it by the years covered by Eusebius' text, multiplying it by the fraction of the Roman world the province of Palestine represents, and multiplying that figure by the total period of the persecution.[76] Subsequent estimates have followed the same basic methodology.[77]

Eusebius' aims in the Martyrs of Palestine have been disputed. Geoffrey de Ste Croix, historian and author of a pair of seminal articles on the persecution of Christians in the Roman world, argued, after Gibbon, that Eusebius aimed at producing a full account of the martyrs in his province. Eusebius' aims, Ste Croix argued, were clear from the text of the Martyrs: after describing Caesarea's martyrdoms for 310, the last to have taken place in the city, Eusebius writes, "Such were the martyrdoms which took place at Cæsarea during the entire period of the persecution"; after describing the later mass executions at Phaeno, Eusebius writes, "These martyrdoms were accomplished in Palestine during eight complete years; and of this description was the persecution in our time."[78] Timothy Barnes, however, argues that Eusebius' intent was not as broad as the text cited by Ste Croix implies: "Eusebius himself entitled the work "About those who suffered martyrdom in Palestine," and his intention was to preserve the memories of the martyrs whom he knew, rather than to give a comprehensive account of how persecution affected the Roman province in which he lived."[79] The preface to the long recension of the Martyrs is cited:

It is meet, then, that the conflicts which were illustrious in various districts should be committed to writing by those who dwelt with the combatants in their districts. But for me, I pray that I may be able to speak of those with whom I was personally conversant, and that they may associate me with them – those in whom the whole people of Palestine glories, because even in the midst of our land, the Saviour of all men arose like a thirst-quenching spring. The contests, then, of those illustrious champions I shall relate for the general instruction and profit.

Martyrs of Palestine (L) pr. 8, tr. Graeme Clark[80]

The text discloses unnamed companions of the martyrs and confessors who are the focus of Eusebius' text; these men are not included in the tallies based on the Martyrs.[81]

See also

- Acts of the Martyrs

- Christian martyrs

- Damnatio ad bestias

- Hellenistic religion

- Interpretatio graeca

- Martyrdom of Polycarp

- New-martyr

- Scillitan Martyrs

References

- 1 2 "Persecution in the Early Church". Religion Facts. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- 1 2 3 4 Moss, Candida (2013). The Myth of Persecution. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-210452-6.

- ↑ Martin, D. 2010. "The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation (lecture transcript). Yale University.

- ↑ Sherwin-White, A.N. "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted? -- An Amendment." Past & Present. Vol. 47 No. 2 (April 1954): 23.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 128.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity, p. 82 Archived June 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "As the existence of the Christians became more widely known, it became increasingly clear that they were (a) antisocial, in that they did not participate in the normal social life of their communities; (b) sacrilegious, in that they refused to worship the gods; and (c) dangerous, in that the gods did not take kindly to communities that harbored those who failed to offer them cult. By the end of the second century, the Christian apologist (literally, 'defender' of the faith) Tertullian complained about the widespread perception that Christians were the source of all disasters brought against the human race by the gods. 'They think the Christians the cause of every public disaster, of every affliction with which the people are visited. If the Tiber rises as high as the city walls, if the Nile does not send its waters up over the fields, if the heavens give no rain, if there is an earthquake, if there is famine or pestilence, straightway the cry is, "Away with the Christians to the lion!"' (Apology 40)" - Bart D. Ehrman, A Brief Introduction to the New Testament (Oxford University Press 2004 ISBN 978-0-19-536934-2), pp. 313–314

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Wordsworth Editions 1998 ISBN 978-1-85326499-3), p. 309

- ↑ Decline & Fall p. 311; Martin Goodman notes that some Christians, following the line taken by the Book of Revelation condemned Rome as evil, the "Whore of Babylon", revelling in its impending downfall. Rome & Jerusalem, p. 531, ISBN 978-0-14-029127-8

- 1 2 De Ste Croix, "Aspects of the 'Great' Persecution," 103.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, G.E.M. "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" Past & Present. Vol. 26. (1963): 123.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 114-115.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 116.

- ↑ Pliny the Younger. Epistulae 10.96-97 at www.earlychristianwritings.com/pliny.html on June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Barnes, T.D. "Legislation Against the Christians." The Journal of Roman Studies. Vol. 58. (1968): 35.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 124.

- ↑ Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians," 37.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 117.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 132.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, G.E.M. "Aspects of the 'Great' Persecution." Harvard Theological Review. Vol. 47. No. 2. (April 1964): 75-78.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 121.

- ↑ De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 122.

- ↑ Barnes, "The Piety of a Persecutor."

- 1 2 De Ste Croix, "Why Were the Early Christians Persecuted?" 135

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, The Crisis Under Gaius Caligula, pages 254–256: "The reign of Gaius Caligula (37-41) witnessed the first open break between the Jews and the Julio-Claudian empire. Until then — if one accepts Sejanus' heyday and the trouble caused by the census after Archelaus' banishment — there was usually an atmosphere of understanding between the Jews and the empire ... These relations deteriorated seriously during Caligula's reign, and, though after his death the peace was outwardly re-established, considerable bitterness remained on both sides. ... Caligula ordered that a golden statue of himself be set up in the Temple in Jerusalem. ... Only Caligula's death, at the hands of Roman conspirators (41), prevented the outbreak of a Jewish-Roman war that might well have spread to the entire East."

- ↑ Wylen, Stephen M., The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction, Paulist Press (1995), ISBN 0-8091-3610-4, Pp 190–192.; Dunn, James D.G., Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, CE 70 to 135, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (1999), ISBN 0-8028-4498-7, Pp 33–34.; Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro & Gargola, Daniel J & Talbert, Richard John Alexander, The Romans: From Village to Empire, Oxford University Press (2004), ISBN 0-19-511875-8, p. 426.;

- ↑ Robert L. Wilkin, ibid., p. 19.

- ↑ Janssen, L.F. "'Superstitio' and the Persecution of the Christians." Vigilae Christianae. Vol. 33 No. 2 (June 1979): 138.

- ↑ Janssen, "'Superstitio' and the Persecution of the Christians," 135-136.

- ↑ "The World of Late Antiquity", Peter Brown, p. 17, Thames and Hudson, 1971, ISBN 0-500-32022-5

- ↑ Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5.1.7.

- ↑ Tertullian's readership was more likely to have been Christians, whose faith was reinforced by Tertullian's defenses of faith against rationalizations.

- 1 2 3 4 5 de Ste. Croix, Geoffrey Ernest Maurice. "Why Were Early Christians Persecuted?". Past & Present , No. 26 (Nov., 1963), pp. 105–152.

- ↑ Frend, W.H.C.. Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church: A Study of a Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus (1967), p. 130

- ↑ Frend, W.H.C.. Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church: A Study of a Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus (1967), p. 125.

- ↑ Timothy D. Barnes, Chapter 11 ("Persecution") in Tertullian (1971, revised 1985). p. 145.

- ↑ Timothy D. Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians," Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58 (1968) p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Timothy D. Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians," Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58 (1968): 32-50.

- ↑ Barnes "Legislation" 35

- ↑ Smallwood, E.M. Classical Philology 51, 1956.

- 1 2 Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament, pp. 805–809. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- ↑ Thompson, Leonard L. Reading the Book of Revelation. "Ordinary Lives" pg. 29–30

- ↑ Merrill, E.T. Essays in Early Christian History (London:Macmillan, 1924).

- ↑ Willborn, L.L. Biblical Research 29 (1984).

- ↑ Thompson, L.L. The Book of Revelation: Apocalypse and Empire (New York: Oxford, 1990).

- ↑ Timothy D. Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians," Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58 (1968): p. 36

- ↑ Timothy D. Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians," Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58 (1968): p. 37

- ↑ Text of the two letters

- ↑ Leon H. Canfield, The Early Persecutions of the Christians (The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd 2005 ISBN 978-1-58477-481-5), pp. 86–99

- ↑ Stephen Benko, Pagan Rome and the Early Christians (Indiana University Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-253-20385-4), pp. 5–13

- ↑ Eyewitness to History: What to do with the Christians? 112 AD

- ↑ Frend, William H.C. "Persecution in the Early Church". Christian History (27): 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Barnes, "Legislation" pg. 154

- ↑ Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 12, pg 616

- ↑ Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 12, pg 617

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2009). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 295. ISBN 0306818302.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints, "Martyrs of Lyons"

- 1 2 3 Tabbernee, William (2007). Fake Prophecy and Polluted Sacraments: Ecclesiastical and Imperial Reactions to Montanism (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae). Brill. ISBN 978-9004158191.

- ↑ Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 12, pg 623

- ↑ Bomgardner, D.L. (October 10, 2002). The Story of the Roman Amphitheatre. Routledge. pp. 141–143. ISBN 978-0415301855.

- ↑ Hopkins, Keith (2011). The Colosseum. Profile Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-1846684708.

- 1 2 W. H. C. Frend (1984). The Rise of Christianity. Fortress Press, Philadelphia. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-8006-1931-2.

- ↑ Philip F. Esler, ed. (2000). The Early Christian World, Vol.2. Routledge. pp. 827–829. ISBN 978-0-415-16497-9.

- ↑ Candida Moss (2013). The Myth of Persecution. HarperCollins. pp. 145–151. ISBN 978-0-06-210452-6.

- ↑ "Pliny's letter to Trajan, translated".

- ↑ Chris Scarre (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: the reign-by-reign record of the rulers of Imperial Rome. Thames & Hudson. p. 170. ISBN 0-500-05077-5.

- ↑ Moss,p.151

- ↑ Frend,p.325

- ↑ Frend,326

- ↑ quoted in Frend, page 327

- ↑ G.W. Bowersock, Martyrdom and Rome (Cambridge University Press 2002 ISBN 978-0-521-53049-1), pp. 1–4; Eusebius describes three men in Caeserea who watched other Christians "winning the crown of martyrdom" and provoked the governor to attain the same end, he records a further six men in the same area demanding to be killed in the arena. Fox, 1987, p. 442–443

- ↑ Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance", H. A. Drake, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8018-7104-2, p. 403; "Christianity & Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries", Ramsay MacMullen, 1997, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07148-5 p.15

- ↑ Geoffrey de Ste Croix, "Aspects of the 'Great' Persecution", Harvard Theological Review 47:2 (1954), 100–1; W. H. C. Frend, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (orig. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1965, rept. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1981), 535–36.

- ↑ Keith Hopkins, "Christian Number and Its Implications", Journal of Early Christian Studies 6:2 (1998), 186–87.

- ↑ Ste Croix, 101

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ed. David Womersley (London: Allen Lane, 1994), 1.578.

- ↑ T. D. Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 154, 357 n. 55.

- ↑ Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine (S) 11.31, 13.11, tr. A. C. McGiffert, cited by Ste Croix, 101.

- ↑ Barnes, 154.

- ↑ Graeme Clark, "Third-Century Christianity", in the Cambridge Ancient History 2nd ed., volume 12: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337, ed. Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 658–69.

- ↑ Clarke, 659.

Sources

- Candida Moss, The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (2013) excerpt and text search

- Castelli, Elizabeth. Martyrdom and Memory: Early Christian Culture Making (2007) excerpt and text search

- W.H.C. Frend, 1965. Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church

- This Holy Seed: Faith, Hope and Love in the Early Churches of North Africa Robin Daniel, (Chester, Tamarisk Publications, 2010: from www.opaltrust.org) ISBN 978-0-9538565-3-4

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "article name needed". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- Robin Lane Fox, 1986, "Pagans and Christians", Viking, ISBN 0-670-80848-2

- G. E. M. de Ste. Croix "Why Were The Early Christians Persecuted?", A Journal of Historical Studies, November 1963, pp. 6–38. Page references in this article relate to a reprint of this essay in "Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, And Orthodoxy", Oxford University Press, 2006

ISBN 0-19-927812-1

Historiography

- Moss, Candida R. "Current Trends in the Study of Early Christian Martyrdom," Bulletin for the Study of Religion (2012) 41#3 Moss's bibliography

External links

- Graeme Clark, "Christians and the Roman State 193-324"

- Early Church History Timeline

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Martyrs

- Persecution in the Early Church