Anti-Catholicism

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Status by country

|

||||||||||

| Religion portal | ||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy and adherents.[6]

After the Reformation and until at least the late 20th Century, majority Protestant states (especially England, Germany, the United States, and Canada) made anti-Catholicism and opposition to the Pope and Catholic rituals major political themes, with anti-Catholic sentiment at times leading to violence and religious discrimination against Catholic individuals (often derogatorily referred to in Anglophone Protestant countries as "papists" or "Romanists"). Historically, Catholics in Protestant countries were frequently (and almost always baselessly) suspected of conspiring against the state in furtherance of papal interests or to establish a political hegemony under the "Papacy", with Protestants sometimes questioning Catholic individuals' loyalty to the state and suspecting Catholics of ultimately maintaining loyalty to the Vatican rather than their domiciled country. In majority Protestant countries with large scale immigration, such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, suspicion or discrimination of Catholic immigrants often overlapped or conflated with nativism, xenophobia, and ethnocentric or racist sentiments (i.e. anti-Italianism, anti-Irish sentiment, hispanophobia, anti-Quebec sentiment, anti-Polish sentiment).

In the Early modern period, in the face of rising secular powers in Europe, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in primarily Catholic nations. As a result of these struggles, there arose in some majority Catholic countries (especially among those individuals with certain secular political views) a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Pope and the clergy in the form of anti-clericalism.

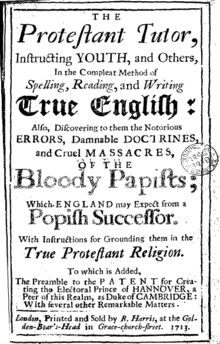

In primarily Protestant countries

Many Protestant reformers, including John Wycliffe, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, John Knox, Roger Williams, Cotton Mather, and John Wesley, as well as most Protestants of the 16th-18th centuries, identified the Pope as the Antichrist. The fifth round of talks in the Lutheran–Roman Catholic dialogue notes,

In calling the pope the "antichrist", the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and heretics but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of power.[7]

Doctrinal materials of the Lutherans, Reformed churches, Presbyterians, Baptists, Anabaptists, and Methodists contain references to the Pope as Antichrist, including Smalcald Articles, Article four (1537),[8] Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope (1537),[9] Westminster Confession, Article 25.6 (1646), and 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith, Article 26.4. In 1754, John Wesley published his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, which is currently an official Doctrinal Standard of the United Methodist Church. In his notes on Revelation chapter 13, he commented: "The whole succession of Popes from Gregory VII are undoubtedly antichrist. Yet this hinders not, but that the last Pope in this succession will be more eminently the antichrist, the man of sin, adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit."[10][11]

Referring to the Book of Revelation, Edward Gibbon stated that "The advantage of turning those mysterious prophecies against the See of Rome, inspired the Protestants with uncommon veneration for so useful an ally."[12] Protestants condemned the Catholic policy of mandatory celibacy for priests.[13]

Britain and British Empire

Great Britain

Institutional anti-Catholicism in Britain and Ireland began with the English Reformation under Henry VIII. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More and John Fisher were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

Queen Mary, Henry's daughter, was a devout Catholic and as queen (1553–58) for five years tried to reverse the Reformation. She married the Catholic king of Spain and executed Protestant leaders. Protestants reviled her as "Bloody Mary".[14]

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power in alliance with arch-enemy France or Spain. In 1570, Pope Pius V sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once. The Recusancy Acts, making it a legal obligation to worship in the Anglican faith, date from Elizabeth's reign.

Assassination plots in which Catholics were prime movers fueled anti-Catholicism in England. These included the famous Gunpowder Plot, in which Guy Fawkes and other conspirators plotted to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session.[15] The fictitious "Popish Plot" involving Titus Oates was a hoax that many Protestants believed to be true, exacerbating Anglican-Catholic relations.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689 involved the overthrow of King James II, of the Stuart dynasty, who favoured the Catholics, and his replacement by a Dutch Protestant. For decades the Stuarts were supported by France in plots to invade and conquer Britain, and anti-Catholicism persisted.[16]

Finally after great political turmoil the Catholics were "emancipated" in the early 19th century—that is, freed from most of the penalties and restrictions they faced. Anti-Catholic attitudes continued, however.[17]

Since World War II anti-Catholic feeling in England has abated somewhat. Ecumenical dialogue between Anglicans and Catholics culminated in the first meeting of an Archbishop of Canterbury with a Pope since the Reformation when Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher visited Rome in 1960.[18] Since then, dialogue has continued through envoys and standing conferences.

Conflict and rivalry between Catholicism and Protestantism since the 1920, and especially since the 1960s, has centred in the Troubles in Northern Ireland.[19]

Anti-Catholicism in Britain was long represented by the burning of an effigy of the Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes at widespread celebrations on Guy Fawkes Night every 5 November.[20] This celebration has, however, largely lost any anti-Catholic connotation. Only faint remains of anti-Catholicism are found today.[21]

Ireland

As punishment for the rebellion of 1641, almost all lands owned by Irish Catholics were confiscated and given to Protestant settlers. Under the penal laws, no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691.[22] Catholic / Protestant strife has been blamed for much of "The Troubles", the ongoing struggle in Northern Ireland.

The English Protestant rulers killed many thousands of Irish people (mostly Catholics) who refused to acknowledge the government and sought alliance with Catholic France, England's great enemy. General Oliver Cromwell, England's military dictator (1653–58) launched a full-scale military attack on Catholics in Ireland, (1649–53). Frances Stewart explains: "Faced with the prospect of an Irish alliance with Charles II, Cromwell carried out a series of massacres to subdue the Irish. Then, once Cromwell had returned to England, the English Commissary, General Henry Ireton adopted a deliberate policy of crop burning and starvation, which was responsible for the majority of an estimated 600,000 deaths out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000."[23]

In addition to the military conflict and occupation, 50,000 women, children, and men were forcibly removed from Ireland and sent to Bermuda and Barbados as indentured servants.[24]

Laws that restricted the rights of Irish Catholics

The Irish potato famine was due in part to Anti-Catholic laws. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Irish Catholics had been prohibited by the penal laws from purchasing or leasing land, from voting, from holding political office, from living in or within 5 miles (8 km) of a corporate town, from obtaining education, from entering a profession, and from doing many other things necessary for a person to succeed and prosper in society. The laws had largely been reformed by 1793, and in 1829, Irish Catholics could again sit in parliament following the Act of Emancipation.[25]

Canada

Fears of the Catholic Church were quite strong in the 19th century, especially among Presbyterian and other Protestant Irish immigrants across Canada.[26] In 1853, the Gavazzi Riots left 10 dead in Quebec in the wake of Catholic Irish protest against Anti-catholic speeches by ex-monk Alessandro Gavazzi.[27][28] The most influential newspaper in Canada was The Globe of Toronto, edited by George Brown a Presbyterian immigrant from Ireland. He vehemently ridiculed and denounced the Catholic Church, Jesuits, priests, nunneries, etc.[29] Irish Protestants remained a political force into the 20th century with many belonging to the Orange Order.[30] It was an anti-Catholic organization with chapters across Canada. It was most powerful during the late 19th century.[31][32]

French language schools

One of the most serious flashpoints year in and year out was public support for Catholic French language schools. Although the Confederation Agreement of 1867 guaranteed the status of Catholic schools where they had been legalized, disputes erupted in numerous provinces, especially in the Manitoba Schools Question in the 1890s and Ontario in the 1910s.[33] in Ontario Regulation 17 was a regulation by the Ontario Ministry of Education, that restricted the use of French as a language of instruction to the first two years of schooling. French Canada reacted vehemently, and lost, dooming its French language Catholic schools. This became a central reason why French Canada distanced itself from the World War I effort, as its young men refused to enlist.[34]

Protestant elements succeeded in blocking the growth of French-language Catholic public schools. However, the Irish Catholics generally supported the English language position advocated by the Protestants.[35]

Newfoundland

Newfoundland long experienced social and political tensions between the large Irish Catholic working-class, on the one hand and the Anglican elite on the other.[36] In the 1850s, the Catholic bishop organized his flock and made them stalwarts of the Liberal party. Nasty rhetoric was the prevailing style elections; bloody riots were common during the 1861 election.[37] The Protestants narrowly elected Hugh Hoyles as the Conservative Prime Minister. Hoyles unexpectedly reversed his long record of militant Protestant activism and worked to defuse tensions. He shared patronage and power with the Catholics; all jobs and patronage were split between the various religious bodies on a per capita basis. This 'denominational compromise' was further extended to education when all religious schools were put on the basis which the Catholics had enjoyed since the 1840s. Alone in North America Newfoundland had a state funded system of denominational schools. The compromise worked and politics ceased to be about religion and became concerned with purely political and economic issues.[38]

Australia

The presence of Catholicism in Australia came with the 1788 arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney. The colonial authorities blocked a Catholic clerical presence until 1820, reflecting the legal disabilities of Catholics in Britain. Some of the Irish convicts had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion and authorities remained suspicious of the minority religion.[39]

Catholic convicts were compelled to attend Church of England services and their children and orphans were raised as Anglicans.[40] The first Catholic priests to arrive came as convicts following the Irish 1798 Rebellion. In 1803, one Fr Dixon was conditionally emancipated and permitted to celebrate Mass, but following the Irish led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804, Dixon's permission was revoked. Fr Jeremiah Flynn, an Irish Cistercian, was appointed as Prefect Apostolic of New Holland and set out uninvited from Britain for the colony. Watched by authorities, Flynn secretly performed priestly duties before being arrested and deported to London. Reaction to the affair in Britain led to two further priests being allowed to travel to the colony in 1820.[39] The Church of England was disestablished in the Colony of New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836. Drafted by the Catholic attorney-general John Plunkett, the act established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists.

By the late 19th century approximately a quarter of the population of Australia were Irish Australians.[41] Many were descended from the 40,000 Irish Catholics who were transported as convicts to Australia before 1867. The majority consisted of British and Irish Protestants. The Catholics dominated the labour unions and the Labor Party. The growth of school systems in the late 19th century typically involved religious issues, pitting Protestants against Catholics. The issue of independence for Ireland was long a sore point, until the matter was resolved by the Irish War of Independence.[42]

Limited freedom of belief is protected by Section 116 of the Constitution of Australia, but sectarianism in Australia persisted into the twentieth century, flaring during the First World War, again reflecting Ireland's place within the Empire, and the Catholic minority remained subject to discrimination and suspicion.[43] During the First World War, the Irish gave support for the war effort and comprised 20% of the army in France.[44] However, the labour unions and the Irish in particular, strongly opposed conscription, and in alliance with like-minded farmers, defeated it in national plebiscites in 1916 and 1917. The Anglicans in particular talked of Catholic "disloyalty".[45] By the 1920s, Australia had its first Catholic prime minister.[46] In the late twentieth century, the Catholic Church replaced the Anglican Church as the largest Christian Church in Australia, and by the twenty-first century, although Protestants remain a majority. Anti-Catholicism is minimal in modern Australia, although it persists in some quarters.[47][48]

Following the Second World War the Labour movement and the Australian Labor Party came more and more under the influence of the Moscow-controlled Australian Communist Party and this struggle resulted in the Australian Labor Party split of 1955 resulting in the creation of the anti-Communist “Democratic Labor Party” with whom the more Catholic dominated unions were aligned. Politically this was damaging to the ALP who did not regain office at the Federal level for another 17 years.

New Zealand

According to New Zealand scholar Michael King, the situation in New Zealand has never been as clear as it was in Australia. Catholics first arrived in New Zealand in 1769. The Church has had "a continuous presence there from the time of the permanent settlement by Irish Catholics in the 1820s, and the first conversions of Maori in the 1830s."[49] However the achievement of the English to gain Maori signatures to a "Treaty" in 1840, created a dominant Protestant country, though French Jean Baptiste Pompallier was able to include a clause about guaranteed freedom of religion in the text.[50] Some sectarian violence was evident in New Zealand in the late 19th century and early twentieth, particularly when New Zealand sent men to fight in World War One, while at the same time (1916) Ireland was aiming for independence from Britain. Many wooden churches in New Zealand (of all religions) have been destroyed by arson.

In the 21st century, Catholicism expresses itself as a left-wing social movement, which includes Jim Anderton; however, other children of established Catholic families have entered politics, where they tend to join right-wing individualist forces (Jim Bolger, Peter Dunne, Gerry Brownlee). King notes (p. 183) that Bolger (centre-right wing National Party) was the country's fourth Catholic Prime Minister. A previous Catholic Prime Minister was Michael Joseph Savage, who instigated numerous social reforms, evidence that since the 1930s, Catholics have been more at odds within their own ranks, than discriminated against in New Zealand society.

Germany

As of 1871, the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in alliance with the liberal majority in parliament took steps to separate state and church, reduce the power of the Catholic Church and crush the Catholic Centre Party. Bismarck suspected the Catholics' foremost loyalty to be with Rome (ultramontanism) instead of the state. The new laws that were passed to that end were met with the strong resistance of the Catholic Church under Pope Pius IX and in turn of the Catholic population thus resulting in a Kulturkampf (literally, "culture struggle").

Priests and bishops who resisted the new laws were fined or arrested. By the height of the Kulturkampf, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laymen were imprisoned for helping the priests.[51] As a result, in consecutive elections the Centre Party grew in numbers which was the opposite of what Bismarck wanted.

Pius IX died in 1878 and was replaced by more conciliatory Pope Leo XIII who negotiated away some of the anti-Catholic laws beginning in 1880.[52][53] Pope Leo officially declared the end of the Kulturkampf on 23 May 1887.

Nazi Germany

The Catholic Church faced repression in Nazi Germany (1933-1945). Hitler despised the Church although he had been brought up in a Catholic home. The long term aim of the Nazis was to de-Christianise Germany.[55][56] Richard J. Evans writes that Hitler believed that in the long run National Socialism and religion would not be able to co-exist, and he stressed repeatedly that Nazism was a secular ideology, founded on modern science: "Science, he declared, would easily destroy the last remaining vestiges of superstition". Germany could not tolerate the intervention of foreign influences such as the Pope and "Priests, he said, were 'black bugs', 'abortions in black cassocks'".[57] Nazi ideology desired the subordination of the church to the state and could not accept an autonomous establishment, whose legitimacy did not spring from the government.[58] From the beginning, the Catholic Church faced general persecution, regimentation and oppression.[59] Aggressive anti-Church radicals like Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann saw the conflict with the Churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.[60] To many Nazis, Catholics were suspected of insufficient patriotism, or even of disloyalty to the Fatherland, and of serving the interests of "sinister alien forces".[61]

Adolf Hitler had some regard for the organisational power of Catholicism, but towards its teachings he showed only the sharpest hostility, calling them "the systematic cultivation of the human failure":[62] To Hitler, Christianity was a religion fit only for slaves and he detested its ethics. Alan Bullock wrote: "Its teaching, he declared, was a rebellion against the natural law of selection by struggle and the survival of the fittest". From political considerations, Hitler was prepared to restrain his anti-clericalism, seeing danger in strengthening the Church by persecution, but intended a show-down after the war.[63] Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Propaganda, led the Nazi persecution of the Catholic clergy and wrote that there was "an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view".[60] Hitler's chosen deputy, Martin Bormann, was a rigid guardian of Nazi orthodoxy and saw Christianity and Nazism as "incompatible", as did the official Nazi philosopher, Alfred Rosenberg, who wrote in "Myth of the Twentieth Century" (1930) that Catholics were among the chief enemies of the Germans.[64][65][66] In 1934, the Sanctum Officium put Rosenberg's book on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (forbidden books list of the Church) for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion".[67]

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies.[68] Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism, rounding up members of the Catholic aligned Bavarian People's Party and Catholic Centre Party, which ceased to exist in early July 1933. Vice Chancellor Papen meanwhile, amid continuing molestation of Catholic clergy and organisations, negotiated a Reich concordat with the Holy See, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[69][70] Hitler then proceeded to close all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:[71]

It quickly became clear that [Hitler] intended to imprison the Catholics, as it were, in their own churches. They could celebrate mass and retain their rituals as much as they liked, but they could have nothing at all to do with German society otherwise. Catholic schools and newspapers were closed, and a propaganda campaign against the Catholics was launched.— Extract from An Honourable Defeat by Anton Gill

Almost immediately after agreeing the Concordat, the Nazis promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church and moved to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[72] In Hitler's Night of the Long Knives purge, Erich Klausener, the head of Catholic Action, was assassinated.[73] Adalbert Probst, national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, Fritz Gerlich, editor of Munich's Catholic weekly and Edgar Jung, one of the authors of the Marburg speech, were among the other Catholic opposition figures killed in the purge.[74]

By 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical - accusing the Nazis of violations of the Concordat, and of sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". The Pope noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany.[72] The Nazis responded with, an intensification of the Church Struggle.[60] There were mass arrests of clergy and church presses were expropriated.[75] Goebbels renewed the regime's crackdown and propaganda against Catholics. By 1939 all Catholic denominational schools had been disbanded or converted to public facilities.[76] By 1941, all Church press had been banned.

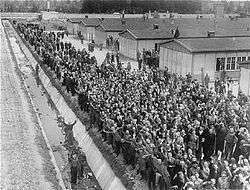

Later Catholic protests included the 22 March 1942 pastoral letter by the German bishops on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church".[77] About 30 per cent of Catholic priests were disciplined by police during the Nazi era.[78] In effort to counter the strength and influence of spiritual resistance, the security services monitored Catholic clergy very closely - instructing that agents monitor every diocese, that the bishops' reports to the Vatican should be obtained and that bishops' activities be discovered and reported.[79] Priests were frequently denounced, arrested, or sent to concentration camps – many to the dedicated clergy barracks at Dachau. Of a total of 2,720 clergy imprisoned at Dachau, some 2,579 (or 94.88%) were Catholic.[54] Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where the Nazis set about systematically dismantling the Church - arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen were murdered.[80][81][82]

United States

.jpg)

John Highham described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".[83] British anti-Catholicism was exported to the United States. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.[84]

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people".[85]

Colonial era

American anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Protestant Reformation which generated anti-Catholic propaganda for various political and dynastic reasons. Because the Protestant Reformation justified itself as an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Catholic bishops and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to New England by English colonists who were predominantly Puritans. They opposed not only the Catholic Church but also the Anglican Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of some Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently "reformed". Furthermore, English and Scottish identity to a large extent was based on opposition to Catholicism. "To be English was to be anti-Catholic," writes Robert Curran.[86]

Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia".[87] Colonial charters and laws often contained specific proscriptions against Catholics. For example, the second Massachusetts charter of October 7, 1691 decreed "that forever hereafter there shall be liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God to all Christians, except Papists, inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within, such Province or Territory".[88]

Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts. One of the Intolerable Acts passed by the British Parliament that helped fuel the American Revolution was the Quebec Act of 1774. Granting freedom of worship to Roman Catholics in Canada, the Quebec Act was seen as an attempt by the British Crown to extend papal rule into the colonies.

New nation

Fear of the pope agitated some of America's Founding Fathers. For example, in 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to prohibit Catholics from holding office. The legislature refused, but did pass a law designed to reach the same goal by requiring all office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil".[89] Thomas Jefferson, looking at the Catholic Church in France, wrote, "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government",[90] and "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."[91]

1840s–1850s

Anti-Catholic fears reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Some claimed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.[92] The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence in several cities. For example, the Philadelphia Nativist Riot and Bloody Monday. In the Orange Riots in New York City in 1871 and 1872, Catholics attacked Protestant Irish.[93] This fear was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

Anti-Catholicism among American Jews further intensified in the 1850s during the international controversy over the Edgardo Mortara case, when a baptized Jewish boy in the Papal States was removed from his family and refused to return to them.[94]

After 1875 many states passed constitutional provisions, called "Blaine Amendments", forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools.[95][96] In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school even if the school were religious.[97]

20th century

Anti-Catholicism played a major role in the defeat of Al Smith, the Democratic nominee for President in 1928. Smith did very well in Catholic districts, but poorly in the South, and in Lutheran areas of the North. His candidacy was also hampered by his close ties with the notorious Tammany Hall political machine in New York City and his strong opposition to prohibition. His cause was in any case uphill, facing a popular Republican in a year of peace and unprecedented prosperity.[98]

The adoption of the 18th Amendment in 1919, a culmination of a half-century of anti-liquor agitation, also fueled anti-Catholic sentiment. Prohibition enjoyed strong support among dry pietistic Protestants, and equally strong opposition by wet Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans. The drys focused their distrust on the Catholics and they gave little popular support to the enforcement of prohibition laws, and when the Great Depression began in 1929 there was increasing sentiment that the government needed the tax revenue that repeal of Prohibition would bring.[99]

Over 10 million Protestant soldiers who served in World War II came into close contact with Catholic soldiers; they got along well and, after the war, they played the central role in spreading high new levels of ethnic and religious tolerance for Catholics among other white Americans.[100] Although anti-Catholic sentiment in the U.S. declined in the 1960s after John F. Kennedy became the first Catholic U.S. president,[101] it persists and is one of the few accepted bigotries in the media and popular culture.[102]

In primarily Catholic countries

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious (generally Catholic) institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. It suggests a more active and partisan role than mere laïcité. The goal of anticlericalism is sometimes to reduce religion to a purely private belief-system with no public profile or influence. However, many times it has included outright suppression of all aspects of faith.

Anticlericalism has at times been violent, leading to murders and the desecration, destruction and seizure of church property. Anticlericalism in one form or another has existed throughout most of Christian history, and is considered to be one of the major popular forces underlying the 16th century reformation. Some of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire, continually attacked the Catholic Church, both its leadership and priests, claiming that many of its clergy were morally corrupt. These assaults in part led to the suppression of the Jesuits, and played a major part in the wholesale attacks on the very existence of the Church during the French Revolution in the Reign of Terror and the program of dechristianization. Similar attacks on the Church occurred in Mexico and in Spain in the twentieth century.

Brazil

Brazil has the largest number of Catholics in the world,[103] and as such it has not experienced any large anti-Catholic movements.

During the Nineteenth Century, the Religious Question was the name given to the crisis when Freemasons in the Brazilian government imprisoned two Catholic bishops for enforcing the Church's prohibition against Freemasonry.

Even during times in which the Church was experiencing intense conservativeness, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship, anti-Catholicism was not advocated by the left-wing movements (instead, Liberation theology gained force). However, with the growing number of Protestants (especially Neo-Pentecostals) in the country, anti-Catholicism has gained strength. A pivotal moment of the rising anti-Catholicism was the kicking of the saint episode in 1995. However, owing to the protests of the Catholic majority, the perpetrator was transferred to South Africa for the duration of the controversy.

Colombia

Anti-Catholic and anti-clerical sentiments, some spurred by an anti-clerical conspiracy theory which was circulating in Colombia during the mid-twentieth century led to persecution of Catholics and killings, most specifically of the clergy, during the events known as La Violencia.[104]

France

During the French Revolution (1789–95) clergy and religious were persecuted and church property was destroyed and confiscated by the new government as part of a process of Dechristianization, the aim of which was the destruction of Catholic practice and of the very faith itself, culminating the imposition of the atheistic Cult of Reason and then the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being.[105] Persecution led Catholics in the west of France to engage in a counterrevolution, the War in the Vendée, and when the state was victorious it killed tens of thousands. A few historians have called it genocide.[106] Most historians say it was a brutal repression of political enemies.[107] The French invasions of Italy (1796–99) included an assault on Rome and the exile of Pope Pius VI in 1798. Relations improved in 1802 when Napoleon came to terms with the Pope in the Concordat of 1801; it allowed the Church to operate but did not give back the lands; it proved satisfactory for a century. By 1815 the Papacy supported the growing alliance against Napoleon, and was re-instated as the state church during the conservative Bourbon Restoration of 1815-30. The brief French Revolution of 1848 again opposed the Church, but the Second French Empire (1851–71) gave it full support. The history of 1789–1871 had established two camps—the left against the Church and the right supporting it—that largely continued until the Vatican II process in 1962–65.[108]

France's Third Republic (1871–1940) was cemented by anti-clericalism, the desire to secularise the State and social life, faithful to the French Revolution.[109] This was the position of the radicals and socialists.[110] The Dreyfus affair again polarised opinion in the 1890s. In the Affaire Des Fiches, in France in 1904–1905, it was discovered that the militantly anticlerical War Minister under Émile Combes, General Louis André, was determining promotions based on the French Masonic Grand Orient's huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic and who attended Mass, with the goal of preventing their promotions.[111]

Italy

In 1860 through 1870, the new Italian government, under the House of Savoy, outlawed all the religious orders, male and female, including the Franciscans, the Dominicans and the Jesuits, closed down their monasteries and confiscated their property, and imprisoned or banished bishops who opposed this (see Kulturkampf).[112][113] Italy took over Rome in 1870 when it lost its French protection; the Pope declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican. Relations were finally normalized in 1929 with the Lateran Treaty.[114]

Mexico

Following the Revolution of 1860, Liberal President Benito Juárez issued a decree nationalizing church property, separating church and state, and suppressing religious orders.

Following the revolution of 1910, the new Mexican Constitution of 1917 contained further anti-clerical provisions. Article 3 called for secular education in the schools and prohibited the Church from engaging in primary education; Article 5 outlawed monastic orders; Article 24 forbade public worship outside the confines of churches; and Article 27 placed restrictions on the right of religious organizations to hold property. Article 130 deprived clergy members of basic political rights.

Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles's enforcement of previous anti-Catholic legislation denying priests' rights, enacted as the Calles Law, prompted the Mexican Episcopate to suspend all Catholic worship in Mexico from August 1, 1926 and sparked the bloody Cristero War of 1926–1929 in which some 50,000 peasants took up arms against the government. Their slogan was "¡Viva Cristo Rey!" (Long live Christ the King!).

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed.[115] Where there were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[115][116] It appears that ten states were left without any priests.[116] Other sources, indicate that the persecution was such that by 1935, 17 states were left with no priests at all.[117]

Some of the Catholic casualties of this struggle are known as the Saints of the Cristero War.[115][118] Events relating to this were famously portrayed in the novel The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene.[119][120]

Poland

For the situation in Russian Poland, see Anticatholicism in Russian Empire

Catholicism in Poland, the religion of the vast majority of the population, was severely persecuted during World War II, following the Nazi invasion of the country and its subsequent annexation into Germany. Over 3 million Catholics of Polish descent were murdered during the Invasion of Poland, including 3 bishops, 52 priests, 26 monks, 3 seminarians, 8 nuns and 9 lay people, later beatified in 1999 by Pope John Paul II as the 108 Martyrs of World War Two.

The Roman Catholic Church was even more violently suppressed in Reichsgau Wartheland and the General Government.[121] Churches were closed, and clergy were deported, imprisoned, or killed,[121] among them was Maximilian Kolbe, a Pole of German descent. Between 1939 and 1945, 2,935 members[122] of the Polish clergy (18%[123]) were killed in concentration camps. In the city of Chełmno, for example, 48% of the Catholic clergy were killed.

Catholicism continued to be persecuted under the Communist regime from the 1950s. Contemporary Stalinist ideology claimed that the Church and religion in general were about to disintegrate. Initially, Archbishop Wyszyński entered into an agreement with the Communist authorities, which was signed on 14 February 1950 by the Polish episcopate and the government. The Agreement regulated the matters of the Church in Poland. However, in May of that year, the Sejm breached the Agreement by passing a law for the confiscation of Church property.

On 12 January 1953, Wyszyński was elevated to the rank of cardinal by Pius XII as another wave of persecution began in Poland. When the bishops voiced their opposition to state interference in ecclesiastical appointments, mass trials and the internment of priests began—the cardinal being one of its victims. On 25 September 1953 he was imprisoned at Grudziądz, and later placed under house arrest in monasteries in Prudnik near Opole and in Komańcza Monastery in the Bieszczady Mountains. He was released on 26 October 1956.

Pope John Paul II, who was born in Poland as Karol Wojtyla, often cited the persecution of Polish Catholics in his stance against Communism.

Switzerland

The Jesuits (Societas Jesu) were banned from all activities in either clerical or pedagogical functions by Article 51 of the Swiss constitution in 1848. The reason for the ban was the perceived threat to the stability of the state resulting from Jesuit advocacy of traditional Catholicism; it followed the Roman Catholic cantons forming an unconstitutional separate alliance leading to civil war. In June 1973, 54.9% of Swiss voters approved removing the ban on the Jesuits (as well as Article 52 which banned monasteries and convents from Switzerland) (See Kulturkampf and Religion in Switzerland)

Spain

Anti-clericalism in Spain at the start of the Spanish Civil War resulted in the killing of almost 7,000 clergy, the destruction of hundreds of churches and the persecution of lay people in Spain's Red Terror.[124] Hundreds of Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War have been beatified and hundreds more were beatified in October 2007.[125][126]

In primarily Orthodox countries

Russian Empire

During the Russian rule, Catholic people, primarily Poles and Lithuans, suffered great persecution not only in terms of their ethnic-national, but also for religious reasons condition. Especially after the uprisings of 1831 and 1863, and within the process of Russification (understanding that there is a strong link between religion and nationality), the tsarist authorities were anxious to promote the conversion of these peoples to the official faith, intervening public education in those regions (which was compulsory education Orthodox religion) and censoring the actions of the Catholic Church.[127] In particular, attention was put into the public acts of the Church, as masses or funerals, which could be the focus of protests against the occupation. Many priests were imprisoned or deported because of his activities in defense of their religion and ethnicity. In the late nineteenth century, however, it was a progressive relaxation in the control of Catholic institutions by the Russian authorities.[128]

Non-Christian nations

Bangladesh

On 3 June 2001 nine people have been killed in a bomb explosion at a Roman Catholic church in the Gopalganj District.[129]

China

The Daoguang Emperor modified existing law making spreading Catholicism punishable by death.[130] During the Boxer Rebellion, Catholic missionaries and their families were murdered by Boxer rebels.[131] During the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion, Tibetan rebels murdered Catholics and Tibetan converts.[132]

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, all religions including Catholicism only operate under state control.[133] However, there are Catholics who do not accept state rule over the Church and worship clandestinely.[134] There has been some rapprochement between the Chinese government and the Vatican.[135]

Japan

On February 5, 1597 a group of twenty-six Catholics were killed on the orders of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[136] During the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japanese Catholics were suppressed leading to an armed rebellion during the 1630s. After the rebellion was defeated, Catholicism were furthered suppressed and many went underground.[137][138] Catholicism was not openly restored to Japan until the 1850s.

North Korea

See Roman Catholicism in North Korea

Sri Lanka

A Buddhist-influenced government took over 600 parish schools in 1960 without compensation and secularized them.[139] Attempts were made by future governments to restore some autonomy.

Within the Catholic Church

The term "anti-Catholic Catholic" has come to be applied to Catholics or ex-Catholics who are perceived to view the Catholic Church with animosity. The term is often used by traditionalist or conservative Catholics to describe modernist or liberal Catholics, especially those who seek to reform doctrine, make secularist critiques of the Catholic Church, or place secular principles above Church teachings.[140][141] Those who take issue with Catholic theology of sexuality are especially prone to this label.[142] According to Hadley Arkes of Crisis Magazine, the archetype of the anti-Catholic Catholic the John F. Kennedy–style politician.[141]

In popular culture

Anti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of English literature, popular fiction, and even pornography. Gothic fiction is particularly rich in this regard. Lustful priests, cruel abbesses, immured nuns, and sadistic inquisitors appear in such works as The Italian by Ann Radcliffe, The Monk by Matthew Lewis, Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin and "The Pit and the Pendulum" by Edgar Allan Poe.[143]

See also

- Category:Critics of the Catholic Church

- Bigotry

- AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power

- Anti-Christian sentiment

- Anti-clerical art

- Anti-Irish racism

- Anti-Polonism

- Anti-Italianism

- Anti-Shi'ism

- Antipope

- Ann Biderman

- Black Legend

- James Carroll

- Jack Chick

- Chick Publications

- Anjem Choudary

- John Cornwell (writer)

- Count's Feud

- Daniel Goldhagen

- Gordon Riots

- Great Apostasy

- Historicism (Christian eschatology)

- International Christian Concern, a Christian human rights NGO whose mission is to help persecuted Christians world-wide

- Institutional Revolutionary Party

- Klansmen: Guardians of Liberty

- The endarkenment

- Ku Klux Klan in Maine

- The Ku Klux Klan In Prophecy

- Hilary Mantel

- Emmett McLoughlin

- The New Anti-Catholicism (book)

- Persecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XII

- Sectarianism in Glasgow

- Ralph Ovadal

- George Templeton Strong

- Vicarius Filii Dei

- Martyrs' Memorial

- Crux Ansata (H.G.Wells book)

- Derogatory terms

- Institutionalized politics, within a country

- Amanda Marcotte

- American Protective Association, U.S. group in 1890s

- Know Nothing

- James G. Blaine

- Protestant Protective Association, Canadian group in 1890s

- Ulster

- Other religions

- Elizabeth: The Golden Age (film)

Notes

- ↑ Oberman, Heiko Augustinus (1 January 1994). "The Impact of the Reformation: Essays". Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing – via Google Books.

- ↑ Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 By Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8006-3735-4

- ↑ HIC OSCULA PEDIBUS PAPAE FIGUNTUR

- ↑ "Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim ban, Und sey nicht so zorniger man. Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre, Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere"

- ↑ Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 (2004), p. 199

- ↑ anti-catholicism. Dictionary.com. WordNet 3.0. Princeton University. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/anti-catholicism (accessed: November 13, 2008).

- ↑ Building Unity, edited by Burgess and Gross, at books.google.com

- ↑ "Smalcald Articles - Book of Concord".

- ↑ Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope in the Triglot translation of the Book of Concord

- ↑ Archived copy at the Library of Congress (May 8, 2009).

- ↑ "UMC.org : the official online ministry of The United Methodist Church".

- ↑ Edward Gibbon (1994 edition edited by David Womersley) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Penguin Books: Vol 1, 469

- ↑ Mark A. Noll; Carolyn Nystrom (2008). Is the Reformation Over?: An Evangelical Assessment of Contemporary Roman Catholicism. Baker Academic. pp. 236–37.

- ↑ David M. Loades, The Reign of Mary Tudor: Politics, Government and Religion in England, 1553–58 (1991)

- ↑ James McConnel, "Remembering the 1605 Gunpowder Plot in Ireland, 1605-1920," Journal of British Studies (2011) 50#4 pp 863-891

- ↑ Colin Haydon, Anti-Catholicism in eighteenth-century England, c. 1714-80: A political and social study (Manchester University Press, 1993)

- ↑ E.R. Norman, Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England (1968)

- ↑ J.R.H. Moorman (1973) A History of the Church in England. London, A&C Black: 457

- ↑ John D. Brewer, and Gareth I. Higgins, Anti-catholicism in Northern Ireland, 1600-1998: the mote and the beam (1998)

- ↑ Steven Roud (2006) The English Year. London, Penguin: 455-63

- ↑ Clive D. Field, "No Popery’s Ghost." Journal of Religion in Europe 7#2 (2014): 116-149.

- ↑ Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery at University of Minnesota Law School

- ↑ Frances Stewart, (2000). War and Underdevelopment: Economic and Social Consequences of Conflict v. 1 (Queen Elizabeth House Series in Development Studies), Oxford University Press.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Sean (2000). To Hell or Barbados. Brandon. p. 86. ISBN 0-86322-287-0.

- ↑ MacManus 1979, pp. 458–459.

- ↑ J. R. Miller, "Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada" in Canadian Historical Review 65, no.4. (December 1985), p. 474+

- ↑ Bernard Aspinwall, "Rev. Alessandro Gavazzi (1808–1889) and Scottish Identity: A Chapter in Nineteenth Century Anti-Catholicism." Recusant History 28#1 (2006): 129-152

- ↑ Dan Horner, "'Shame upon you as men!': Contesting Authority in the Aftermath of Montreal's Gavazzi Riot." Histoire sociale/social history 44.1 (2011): 29-52.

- ↑ J.M.C. Careless, Brown of the Globe: Volume One: Voice of Upper Canada 1818-1859 (1959) 1:172-74

- ↑ James R. Miller, "Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada," Canadian Historical Review (1985) 66#4 pp 474-494.

- ↑ Stephen Kenny, "A Prejudice that Rarely Utters Its Name: A Historiographical and Historical Reflection upon North American Anti-Catholicism," American Review of Canadian Studies (2002) 32#4 pp 639-672

- ↑ See Hereward Senior "Orange Order" in Canadian Encyclopedia (2015).

- ↑ Margaret Prang, "Clerics, Politicians, and the Bilingual Schools Issue in Ontario, 1910–1917." Canadian Historical Review 41.4 (1960): 281-307.

- ↑ Robert Craig Brown, and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896-1921: A nation transformed (1974) pp 253-62

- ↑ Jack Cecillon, "Turbulent Times in the Diocese of London: Bishop Fallon and the French-Language Controversy, 1910–18". Ontario History (1995) 87#4 pp: 369–395.

- ↑ John Edward FitzGerald, Conflict and culture in Irish-Newfoundland Roman Catholicism, 1829-1850 (U of Ottawa, 1997) online online.

- ↑ Jeff A. Webb, "The Election Riots of 1861" (2001) online edition

- ↑ Frederick Jones, "HOYLES, Sir HUGH WILLIAM," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed May 25, 2015, online.

- 1 2 "The Catholic Community in Australia". Catholic Australia. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Australia". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ↑ Mike Cronin; Daryl Adair (2006). The Wearing of the Green: A History of St Patrick's Day. Routledge. p. 19.

- ↑ Patrick O'Farrell, The Irish in Australia (1987) ch 6

- ↑ Griffin, James. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Jeffrey Grey. A Military History of Australia. Cambridge University Press. p. 90.

- ↑ Alan D. Gilbert, "Protestants, Catholics and Loyalty: An Aspect of the Conscription Controversies, 1916-1917," Politics (1971) 6#1 pp 15-25

- ↑ Robertson, J. R. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ "Abbott, Pell and the new sectarianism - Gerard Henderson - www.theage.com.au".

- ↑ "I'll wear ovaries T-shirt again: Nettle - National - smh.com.au".

- ↑ (God's Farthest Outpost, A History of Catholics in New Zealand, Viking, 1997, p. 9)

- ↑ Colenso, William (1890). The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi Wellington: Government Printer. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Helmstadter, Richard J., Freedom and religion in the nineteenth century, p. 19, Stanford Univ. Press 1997

- ↑ Michael B. Gross, The War against Catholicism: Liberalism and the Anti-Catholic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Germany (2005)

- ↑ Ronald J. Ross, The Failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf: Catholicism and State Power in Imperial Germany, 1871–1887 (Catholic University of America Press, 1998)

- 1 2 Paul Berben; Dachau: The Official History 1933-1945; Norfolk Press; London; 1975; ISBN 9780852110096; pp. 276-277

- ↑

- Sharkey, Word for Word/The Case Against the Nazis; How Hitler's Forces Planned To Destroy German Christianity, New York Times, 13 January 2002

- The Nazi Master Plan: The Persecution of the Christian Churches, Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion, Winter 2001, publishing evidence compiled by the O.S.S. for the Nuremberg war-crimes trials of 1945 and 1946

- Griffin, Roger Fascism's relation to religion in Blamires, Cyprian, World fascism: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 10, ABC–CLIO, 2006: "There is no doubt that in the long run Nazi leaders such as Hitler and Himmler intended to eradicate Christianity just as ruthlessly as any other rival ideology, even if in the short term they had to be content to make compromises with it."

- Mosse, George Lachmann, Nazi culture: intellectual, cultural and social life in the Third Reich, p. 240, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2003: "Had the Nazis won the war their ecclesiastical policies would have gone beyond those of the German Christians, to the utter destruction of both the Protestant and the Catholic Church."

- Shirer, William L., Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, p. p 240, Simon and Schuster, 1990: "And even fewer paused to reflect that under the leadership of Rosenberg, Bormann and Himmler, who were backed by Hitler, the Nazi regime intended eventually to destroy Christianity in Germany, if it could, and substitute the old paganism of the early tribal Germanic gods and the new paganism of the Nazi extremists."

- Fischel, Jack R., Historical Dictionary of the Holocaust , p. 123, Scarecrow Press, 2010: "The objective was to either destroy Christianity and restore the German gods of antiquity or to turn Jesus into an Aryan."

- Dill, Marshall, Germany: a modern history , p. 365, University of Michigan Press, 1970: "It seems no exaggeration to insist that the greatest challenge the Nazis had to face was their effort to eradicate Christianity in Germany or at least to subjugate it to their general world outlook."

- Wheaton, Eliot Barculo The Nazi revolution, 1933–1935: prelude to calamity:with a background survey of the Weimar era, p. 290, 363, Doubleday 1968: The Nazis sought "to eradicate Christianity in Germany root and branch."

- ↑ Bendersky, Joseph W., A concise history of Nazi Germany, p. 147, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007: "Consequently, it was Hitler’s long range goal to eliminate the churches once he had consolidated control over his European empire."

- ↑ Richard J. Evans; The Third Reich at War; Penguin Press; New York 2009, p. 547

- ↑ Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair - German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ISBN 0-674-63680-5; p. 196

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann; The History of the German Resistance 1933-1945; 3rd Edn (First English Edn); McDonald & Jane's; London; 1977; p.14

- 1 2 3 Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.381-382

- ↑ Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair - German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ISBN 0-674-63680-5; p. 74

- ↑ Alan Bullock; Hitler, a Study in Tyranny; HarperPerennial Edition 1991; p218

- ↑ Alan Bullock; Hitler: a Study in Tyranny; HarperPerennial Edition 1991; p219"

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Fascism - Identification with Christianity; 2013. Web. 14 Apr. 2013

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Martin Bormann; web 25 April 2013

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Alfred Rosenberg; web 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Richard Bonney; Confronting the Nazi War on Christianity: the Kulturkampf Newsletters, 1936-1939; International Academic Publishers; Bern; 2009 ISBN 978-3-03911-904-2; pp. 122

- ↑ Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair - German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ISBN 0-674-63680-5; p. 136

- ↑ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Company; London; p.290

- ↑ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.295

- ↑ Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.57

- 1 2 William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; p234-5

- ↑ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.315

- ↑ John S. Conway; The Nazi Persecution of the Churches, 1933-1945; Regent College Publishing; 2001; ISBN 1-57383-080-1 (USA); p.92

- ↑ Joachim Fest; Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler 1933-1945; Weidenfield & Nicolson; London; p.374

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3; pp. 245-246

- ↑ Fest, Joachim (1996). Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler 1933–1945. London: Weidenfield & Nicolson; p.377

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3; p.244

- ↑ Paul Berben; Dachau: The Official History 1933-1945; Norfolk Press; London; 1975; ISBN 9780852110096; pp. 141-2

- ↑ Libionka, Dariusz (2004). "The Catholic Church in Poland and the Holocaust, 1939-1945" (PDF). In Carol Rittner, Stephen D. Smith, Irena Steinfeldt. The Holocaust And The Christian World: Reflections On The Past Challenges For The Future. New Leaf Press. pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-0-89221-591-1.

- ↑ "Poles: Victims of the Nazi Era". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Norman Davies; Rising '44: the Battle for Warsaw; Vikiing; 2003; p.92

- ↑ Jenkins, Philip (1 April 2003). The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-515480-1.

- ↑ Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature. Archived from the original on 2009-10-25.

- ↑ "The Coming Catholic Church". By David Gibson. HarperCollins: Published 2004.

- ↑ Robert Emmett Curran, Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574-1783 (2014) pp 201-2

- ↑ Ellis, John Tracy (1956). American Catholicism.

- ↑ The Charter Granted by their Majesties King William and Queen Mary, to the Inhabitants of the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New-England, Publisher: Boston, in New-England: Printed by S. Kneeland, by Order of His Excellency the Governor, Council and House of Representatives, (1759), p. 9.

- ↑ John P. Kaminski, "Religion and the Founding Fathers," Annotation (March 2002) Vol. 30:1 ISSN 0160-8460, online

- ↑ Letter to Alexander von Humboldt, December 6, 1813

- ↑ Jefferson letter to Horatio G. Spafford, March 17, 1814

- ↑ Bilhartz, Terry D. (1986). Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8386-3227-7.

- ↑ Michael Gordon, The Orange riots: Irish political violence in New York City, 1870 and 1871 (1993)

- ↑ Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938.

- ↑ "Blaine -".

- ↑ Tony Mauro (5-20-03). "High court agrees to settle Part II of voucher battle". firstamendmentcenter.org. First Amendment Center. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2015. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bush, Jeb (March 4, 2009). NO:Choice forces educators to improve. The Atlanta Constitution-Journal.

- ↑ Edmund Moore, A Catholic Runs for President (1956)

- ↑ David E. Kyvig, Repealing national prohibition (Kent State University Press, 2000)

- ↑ Thomas A. Bruscino (2010). A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along. U. of Tennessee Press. pp. 214–15.

- ↑ "America's dark and not-very-distant history of hating Catholics". The Guardian. March 7, 2016.

- ↑ Phillip Jenkins, "The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice" (Oxford University Press, 2003)

- ↑ IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics). Religion in Brazil - 2000 Census. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Williford, Thomas J. Armando los espiritus: Political Rhetoric in Colombia on the Eve of La Violencia, 1930–1945 p.217-278 (Vanderbilt University 2005)

- ↑ Tallet, Frank Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789 p. 1-2, 1991 Continuum International Publishing

- ↑ See Reynald Secher. A French Genocide: The Vendee (2003)

- ↑ Farewell, Revolution: Disputed Legacies : France, 1789/1989. Cornell University Press. 1995. p. 100.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age. Vol. I : The 19th Century in Europe; Background and the Roman Catholic Phase (1969), pp 127-46, 399-415

- ↑ Timothy Verhoeven, Transatlantic Anti‐Catholicism: France and the United States in the Nineteenth Century (2010)

- ↑ Foster, J. R.; Jean Marie Mayeur; Madeleine Rebérioux (1 February 1988). The Third Republic from Its Origins to the Great War, 1871–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-35857-6.

- ↑ Franklin 2006, p. 9 (footnote 26) cites Larkin, Maurice, Church and State after the Dreyfus Affair, pp. 138–141: "Freemasonry in France", Austral Light, 6: 164–172, 241–250, 1905

- ↑ Ulrich Muller (2009-11-25). "Congregation of the Most Precious Blood". Catholic Enclopedia 1913. Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Michael Ott (2009-11-25). "Pope Pius IX". Catholic Enclopedia 1913. Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Edward Townley (2002). Mussolini and Italy. Heinemann. p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- 1 2 Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 978-1-57488-452-4

- ↑ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p.393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company) ISBN 978-0-393-31066-5

- ↑ Mark Almond (1996) Revolution: 500 Years of Struggle For Change: 136-7

- ↑ Barbara A. Tenenbaum and Georgette M. Dorn (eds.), Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture (New York: Scribner's, 1996).

- ↑ Stan Ridgeway, "Monoculture, Monopoly, and the Mexican Revolution" Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos 17.1 (Winter, 2001): 143.

- 1 2 John S. Conway, "The Nazi Persecution of the Churches, 1933-1945", Regent College Publishing, 1997

- ↑ Weigel, George (2001). Witness to Hope - The Biography of Pope John Paul II. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-018793-4.

- ↑ Craughwell, Thomas J., The Gentile Holocaust Catholic Culture. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ↑ de la Cueva, Julio "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War" Journal of Contemporary History Vol.33(3) p. 355

- ↑ "NEW EVANGELIZATION WITH THE SAINTS".

- ↑ Stephanie Innes (06-12-2007). "Tucson priests one step away from sainthood". Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2015. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Weeks, Theodore (2001). "Religion and Russification: Russian Language in the Catholic Churches of the "Northwest Provinces" after 1863". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 2 (1).

- ↑ Weeks, Ted (2011). "Religion, nationality, or politics: Catholicism in the Russian empire, 1863–1905". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 2 (1): 52–59.

- ↑ "Bangladesh church bomb kills nine". BBC News. 3 June 2001. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Robert Samuel Maclay (1861). Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China. Carlton & Porter. p. 336. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ Joseph Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising (1987), pp. 190–191; Paul Cohen, History in Three Keys (1997), p. 51.

- ↑ Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General (1904). East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4. LONDON: Printed for H. M. Stationery Off., by Darling. p. 17. Retrieved 2011-06-28.(Original from Harvard University)

- ↑ AsiaNews.it. "CHINA The Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association celebrates 50 years at a less than ideal moment".

- ↑ U.S Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report 2010: China, 17 Nov 2010.

- ↑ "Missing Page Redirect".

- ↑ "Martyrs List". Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ↑ "S". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ↑ "隠れキリシタン" [Kakure Kirishitan]. Dijitaru Daijisen (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ↑ "Catholic Church in Sri Lanka - A History in Outline by W.L.A.Don Peter".

- ↑ Weigel, George (21 June 2011). "Maureen Dowd's Catholic Problem". National Review Online. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- 1 2 Arkes, Hadley (1 November 1996). "Life Watch: Anti-Catholic Catholics". Crisis Magazine. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Lawler, Phil (13 July 2011). "Anti-Catholic Catholics". Catholic Culture. Trinity Communications. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Patrick R O'Malley (2006) Catholicism, sexual deviance, and Victorian Gothic culture. Cambridge University Press

Further reading

- Anbinder; Tyler Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s 1992; in U.s.

- Bennett; David H. The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History University of North Carolina Press, 1988

- Billingon, Ray. The Protestant Crusade, 1830–1860 (1938), on Know Nothings and related groups in US

- Blanshard; Paul.American Freedom and Catholic Power Beacon Press, 1949; famous attack on Catholicism

- Brown, Thomas M. "The Image of the Beast: Anti-Papal Rhetoric in Colonial America", in Richard O. Curry and Thomas M. Brown, eds., Conspiracy: The Fear of Subversion in American History (1972), 1-20.

- Bruce, Steve. No Pope of Rome: Anti-Catholicism in Modern Scotland (Edinburgh, 1985).

- Clifton, Robin. "Popular Fear of Catholics during the English Revolution", Past and Present, 52 (1971), 23-55. in JSTOR

- Cogliano; Francis D. No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England Greenwood Press, 1995

- Davis, David Brion. "Some Themes of Counter-subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic and Anti-Mormon Literature", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (1960), 205-224. in JSTOR

- * Drury, Marjule Anne. "Anti-Catholicism in Germany, Britain, and the United States: A review and critique of recent scholarship." Church History 70#1 (2001): 98-131.

- Franklin, James (2006), "Freemasonry in Europe", Catholic Values and Australian Realities, Connor Court Publishing Pty Ltd, pp. 7–10, ISBN 9780975801543

- Greeley, Andrew M. An Ugly Little Secret: Anti-Catholicism in North America 1977.

- Henry, David. "Senator John F. Kennedy Encounters the Religious Question: I Am Not the Catholic Candidate for President." in Contemporary American Public Discourse Ed. H. R. Ryan. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1992. 177-193.

- Higham; John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 1955

- Hinckley, Ted C. "American Anti-Catholicism During the Mexican War," Pacific Historical Review 1962 31(2): 121-137. in JSTOR

- Hostetler; Michael J. "Gov. Al Smith Confronts the Catholic Question: The Rhetorical Legacy of the 1928 Campaign," Communication Quarterly (1998) 46#1 pp 12+.

- Jenkins, Philip. The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press, New ed. 2004). ISBN 978-0-19-517604-9

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 (1971)

- Jensen, Richard. "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization," Journal of Social History 36.2 (2002) 405-429, with illustrations

- Joskowicz, Ari. The Modernity of Others: Jewish Anti-Catholicism in Germany and France (Stanford University Press; 2013) 376 pages; how Jewish intellectuals defined themselves as modern against the anti-modern positions of the Catholic church

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. Christianity in a Revolutionary Age (5 vol 1969), covers 1790s to 1960; comprehensive global history

- Keating, Karl. Catholicism and Fundamentalism—The Attack on "Romanism" by "Bible Christians" (Ignatius Press, 1988). ISBN 978-0-89870-177-7

- Kenny; Stephen. "Prejudice That Rarely Utters Its Name: A Historiographical and Historical Reflection upon North American Anti-Catholicism," American Review of Canadian Studies. Volume: 32. Issue: 4. 2002. pp: 639+.

- McGreevy, John T. "Thinking on One's Own: Catholicism in the American Intellectual Imagination, 1928–1960." The Journal of American History, 84 (1997): 97-131. in JSTOR

- Miller, J.R. "Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada" in Canadian Historical Review 65, no.4. (December 1985), p. 474+

- Moore; Edmund A. A Catholic Runs for President (1956) on Al Smith in 1928

- Moore; Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921–1928 University of North Carolina Press, 1991

- Norman, E. R. Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England (1968).

- Paz, D. G. "Popular Anti-Catholicism in England, 1850–1851", Albion 11 (1979), 331-359. in JSTOR

- Thiemann, Ronald F. Religion in Public Life Georgetown University Press, 1996.

- Verhoeven Timothy. Transatlantic Anti-Catholicism: France and the United States in the Nineteenth Century (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010) excerpt and text search

- Wiener, Carol Z. "The Beleaguered Isle. A Study of Elizabethan and Early Jacobean Anti-Catholicism", Past and Present, 51 (1971), 27-62.

- Wolffe, John. "North Atlantic Anti-Catholicism in the Nineteenth Century: A Comparative Overview." European Studies: A Journal of European Culture, History and Politics 31#1 (2013): 25-41.

- Wolffe, John, ed., Protestant-Catholic Conflict from the Reformation to the Twenty-first Century (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013). Table of contents

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-Catholicism. |