Politics of Australia

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Australia |

|

|

|

Related topics |

The politics of Australia takes place within the framework of a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Australians elect parliamentarians to the federal Parliament of Australia, a bicameral body which incorporates elements of the fused executive inherited from the Westminster system, and a strong federalist senate, adopted from the United States Congress. Australia largely operates as a two-party system in which voting is compulsory.[1]

Legislative

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, and has been influenced both by the Westminster system and United States federalism. Under Section 1 of the Constitution of Australia, Parliament consists of three components: the Monarch, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. The Australian Parliament is the world's sixth oldest continuous democracy.[2]

The Australian House of Representatives has 150 members, each elected for a flexible term of office not exceeding three years,[3] to represent a single electoral division, commonly referred to as an electorate or seat. Voting within each electorate utilises the instant-runoff system of preferential voting, which has its origins in Australia. The party or coalition of parties which commands the confidence of a majority of members of the House of Representatives forms government.

The Australian Senate has 76 members. The six states return twelve senators each, and the two mainland territories return two senators each, elected through the single transferable voting system. Senators are elected for flexible terms not exceeding six years, with half of the senators contesting at each federal election. The Senate is afforded substantial powers by the Australian Constitution, significantly greater than those of Westminster upper houses such as those of the United Kingdom and Canada, and has the power to block legislation originating in the House as well as supply or monetary bills. As such, the Senate has the power to bring down the government, as occurred during the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis.

Because legislation must pass successfully through both houses to become law, it is possible for disagreements between the House of Representatives and the Senate to hold up the progress of government bills indefinitely. Such deadlocks are resolved under section 57 of the Constitution, under a procedure called a double dissolution election. Such elections are rare, not because the conditions for holding them are seldom met, but because they can pose a significant political risk to any government that chooses to call one. Of the six double dissolution elections that have been held since federation, half have resulted in the fall of a government. Only once, in 1974, has the full procedure for resolving a deadlock been followed, with a joint sitting of the two houses being held to deliberate upon the bills that had originally led to the deadlock.

Executive

The role of head of state in Australia is divided between two people: the monarch of Australia and the Governor-General of Australia. The functions and roles of the Governor-General include appointing ambassadors, ministers and judges, giving Royal Assent to legislation (also a role of the monarch), issuing writs for elections and bestowing honours.[4] The Governor-General is the President of the Federal Executive Council and Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Defence Force. These posts are held under the authority of the Australian Constitution. In practice, barring exceptional circumstances, the Governor-General exercises these powers only on the advice of the Prime-Minister. As such, the role of Governor-General is often described as a largely ceremonial position.

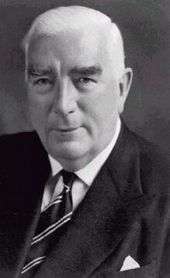

The Prime Minister of Australia is the highest government minister, leader of the Cabinet and head of government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful political office in Australia. Despite being at the apex of executive government in the country, the office is not mentioned in the Constitution of Australia specifically and exists through an unwritten political convention. Barring exceptional circumstances, the prime minister is always the leader of the political party or coalition with majority support in the House of Representatives. The only case where a senator was appointed prime minister was that of John Gorton, who subsequently resigned his Senate position and was elected as a member of the House of Representatives (Senator George Pearce was acting prime minister for seven months in 1916 while Billy Hughes was overseas).[5]

The Cabinet of Australia is the council of senior ministers responsible to Parliament. The Cabinet is appointed by the Governor-General, on the advice of the Prime Minister and serves at the former's pleasure. The strictly private Cabinet meetings occur once a week to discuss vital issues and formulate policy. Outside of the cabinet there are a number of junior ministers, responsible for a specific policy area and reporting directly to any senior Cabinet minister. The Constitution of Australia does not recognise the Cabinet as a legal entity, and its decisions have no legal force. All members of the ministry are also members of the Executive Council, a body which is – in theory, though rarely in practice – chaired by the Governor-General, and which meets solely to endorse and give legal force to decisions already made by the Cabinet. For this reason, there is always a member of the ministry holding the title Vice-President of the Executive Council.

Reflecting the influence of the Westminster system, ministers are selected from elected members of Parliament.[6] All ministers are expected individually to defend collective government decisions. Individual ministers who cannot undertake the public defence of government actions are generally expected to resign. Such resignations are rare; and the rarity also of public disclosure of splits within cabinet reflects the seriousness with which internal party loyalty is regarded in Australian politics.

Judicial

.jpg)

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and interprets the Constitution of Australia. The High Court is mandated by section 71 of the Constitution, which vests in it the judicial power of the Commonwealth of Australia. The High Court was constituted by the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). The High Court is composed of seven Justices: the Chief Justice of Australia, presently Robert French, and six other Justices.

The state supreme courts are also considered to be superior courts, those with unlimited jurisdiction to hear disputes and which are the pinnacle of the court hierarchy within their jurisdictions. They were created by means of the constitutions of their respective states or the Self Government Acts for the ACT and the Northern Territory. Appeals may be made from state supreme courts to the High Court of Australia.

Inferior Courts are secondary to Superior Courts. Their existence stems from legislation and they only have the power to decide on matters which Parliament has granted them. Decisions in inferior courts can be appealed to the Superior Court in that area, and then to the High Court of Australia.

Elections

At a national level, elections are held at least once every three years.[3] The Prime Minister can advise the Governor-General to call an election for the House of Representatives at any time, but Senate elections can only be held within certain periods prescribed in the Australian Constitution. The most recent Australian federal election took place on 2 July 2016.

The House of Representatives is elected using the Australian instant-runoff voting system, which results in the preferences which flow from minor party voters to the two major parties being significant in electoral outcomes. The Senate is elected using the single transferable voting system, which has resulted in a greater presence of minor parties in the Senate. For most of the last thirty years a balance of power has existed, whereby neither government nor opposition has had overall control of the Senate. This limitation to its power, has required governments to frequently seek the support of minor parties or independents to secure their legislative agenda. The ease with which minor parties can secure representation in the Senate compared to the House of Representatives has meant that these parties have often focused their efforts on securing representation in the upper house. This is true also at state level (only the two territories and Queensland are unicameral). Minor parties have only rarely been able to win seats in the House of Representatives.

State and local government

Australia's six states and two territories are structured within a political framework similar to that of the Commonwealth. Each state has its own bicameral Parliament, with the exception of Queensland and the two Territories, whose Parliaments are unicameral. Each state has a Governor, who undertakes a role equivalent to that of the Governor-General at the federal level, and a Premier, who is the head of government and is equivalent to the Prime Minister. Each state also has its own supreme court, from which appeals can be made to the High Court of Australia.

Elections in the six Australian states and two territories are held at least once every four years. In New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, election dates are fixed by legislation. However, the other state premiers and the Chief Minister of the Northern Territory have the same discretion in calling elections as the Prime Minister at national level.

Local government in Australia is the third (and lowest) tier of government, administered by the states and territories which in turn are beneath the federal tier. Unlike the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand, there is only one level of local government in all states, with no distinction such as counties and cities. Today, most local governments have equivalent powers within a state, and styles such as "shire" or "city" refer to the nature of the settlements they are based around.

Ideology in Australian politics

In Australian political culture, the Coalition is considered centre-right and the Labor Party is considered centre-left. Australian conservatism is largely represented by the Coalition, along with Australian liberalism. The Labor Party categorises itself as social democratic,[7] although it has pursued a liberal economic policy since the prime ministership of Bob Hawke.[8]

Queensland, in particular, along with Western Australia and the Northern Territory, are regarded as comparatively conservative.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, and the Australian Capital Territory are regarded as comparatively left of centre.[15][16][17][18][19] New South Wales has often been regarded as a politically moderate bellwether state.[19][20]

Since the 2007 elections, the voting patterns of the Australian electorate have shifted. There is more volatility in the Australian electorate than ever before. More Australian voters are swinging between the two major parties or are voting for third parties, with one in four Australians voting for a minor party.[21]

Political parties

Organised, national political parties have dominated Australia's political landscape since federation. The late 19th century saw the rise of the Australian Labor Party, which represented organised workers. Opposing interests coalesced into two main parties: a centre-right party with a base in business and the middle classes that has been predominantly socially conservative, now the Liberal Party of Australia; and a rural or agrarian conservative party, now the National Party of Australia. While there are a small number of other political parties that have achieved parliamentary representation, these main three dominate organised politics everywhere in Australia and only on rare occasions have any other parties or independent members of parliament played any role at all in the formation or maintenance of governments.

Australian politics operates as a two-party system, as a result of the permanent coalition between the Liberal Party and National Party. Internal party discipline has historically been tight, unlike the situation in other countries such as the United States. Australia's political system has not always been a two-party system, but nor has it always been as internally stable as in recent decades.

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) is a self-described social democratic party which has in recent decades pursued a liberal economic program. It was founded by the Australian labour movement and broadly represents the urban working class, although it increasingly has a base of sympathetic middle class support as well.

The Liberal Party of Australia is a party of the centre-right which broadly represents business, the suburban middle classes and many rural people. Its permanent coalition partner at national level is the National Party of Australia, formerly known as the Country Party, a conservative party which represents rural interests. These two parties are collectively known as the Coalition. In Queensland, and more recently in NSW, the two parties have officially merged to form the Liberal National Party, and in the Northern Territory, the National Party is known as the Country Liberal Party.

Minor parties in Australian politics include a green party, the Australian Greens, the largest of the minor parties; a centrist party, Nick Xenophon Team; a nationalist party, Pauline Hanson's One Nation; and an anti-privatisation party, Katter's Australian Party. Other significant parties in recent years have included the Palmer United Party, the socially conservative Family First Party, and the socially liberal Australian Democrats, among others.

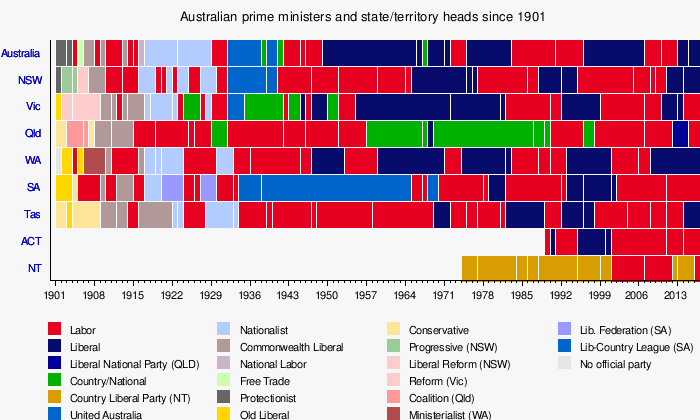

Timeline

Since federation, there have been 29 Prime Ministers of Australia. The longest-serving Prime Minister was Sir Robert Menzies of the Liberal Party, who served for 19 years from 1939–41, and again from 1949–66. The only other Prime Minister to serve for longer than a decade was John Howard, also of the Liberal Party, who led for more than 11 years from 1996–2007. The Coalition and its direct predecessors have governed at the federal level for a large majority of Australia's history since federation: 30,548 days as compared to Labor's 12,252 days.

| Party | Prime Ministers | In Office |

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 7 | 18,281 days |

| Labor | 12 | 12,252 days |

| Nationalist | 2 | 5,114 days |

| United Australia | 1 (2) | 3,508 days |

| Protectionist | 2 | 2,451 days |

| Commonwealth Liberal | 1 (2) | 783 days |

| Free Trade | 1 | 328 days |

| Country | 3 | 83 days |

| Total | 29 | 42,800 days |

|

Lower house primary, two-party and seat results since 1910

A two-party system has existed in the House of Representatives since the two non-Labor parties merged in 1909. The 1910 election was the first to elect a majority government, with the Australian Labor Party concurrently winning the first Senate majority. A two-party-preferred vote (2PP) has been calculated since the 1919 change from first-past-the-post to preferential voting and subsequent introduction of the Coalition. ALP = Australian Labor Party, L+NP = grouping of Liberal/National/LNP/CLP Coalition parties (and predecessors), Oth = other parties and independents.

| Primary vote | 2PP vote | Seats | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP | L+NP | Oth. | ALP | L+NP | ALP | L+NP | Oth. | Total | |

| 2 July 2016 election | 34.7% | 42.0% | 23.3% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 69 | 76 | 5 | 150 |

| 28 Jun – 1 Jul 2016 Newspoll | 35% | 42% | 23% | 49.5% | 50.5% | ||||

| 7 September 2013 election | 33.4% | 45.6% | 21.1% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 55 | 90 | 5 | 150 |

| 3–5 Sep 2013 Newspoll | 33% | 46% | 21% | 46% | 54% | ||||

| 21 August 2010 election | 38.0% | 43.3% | 18.8% | 50.1% | 49.9% | 72 | 72 | 6 | 150 |

| 17–19 Aug 2010 Newspoll | 36.2% | 43.4% | 20.4% | 50.2% | 49.8% | ||||

| 24 November 2007 election | 43.4% | 42.1% | 14.5% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 83 | 65 | 2 | 150 |

| 20–22 Nov 2007 Newspoll | 44% | 43% | 13% | 52% | 48% | ||||

| 9 October 2004 election | 37.6% | 46.7% | 15.7% | 47.3% | 52.7% | 60 | 87 | 3 | 150 |

| 6–7 Oct 2004 Newspoll | 39% | 45% | 16% | 50% | 50% | ||||

| 10 November 2001 election | 37.8% | 43.0% | 19.2% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 65 | 82 | 3 | 150 |

| 7–8 Nov 2001 Newspoll | 38.5% | 46% | 15.5% | 47% | 53% | ||||

| 3 October 1998 election | 40.1% | 39.5% | 20.4% | 51.0% | 49.0% | 67 | 80 | 1 | 148 |

| 30 Sep – 1 Oct 1998 Newspoll | 44% | 40% | 16% | 53% | 47% | ||||

| 2 March 1996 election | 38.7% | 47.3% | 14.0% | 46.4% | 53.6% | 49 | 94 | 5 | 148 |

| 28–29 Feb 1996 Newspoll | 40.5% | 48% | 11.5% | 46.5% | 53.5% | ||||

| 13 March 1993 election | 44.9% | 44.3% | 10.7% | 51.4% | 48.6% | 80 | 65 | 2 | 147 |

| 11 Mar 1993 Newspoll | 44% | 45% | 11% | 49.5% | 50.5% | ||||

| 24 March 1990 election | 39.4% | 43.5% | 17.1% | 49.9% | 50.1% | 78 | 69 | 1 | 148 |

| 11 July 1987 election | 45.8% | 46.1% | 8.1% | 50.8% | 49.2% | 86 | 62 | 0 | 148 |

| 1 December 1984 election | 47.6% | 45.0% | 7.4% | 51.8% | 48.2% | 82 | 66 | 0 | 148 |

| 5 March 1983 election | 49.5% | 43.6% | 6.9% | 53.2% | 46.8% | 75 | 50 | 0 | 125 |

| 18 October 1980 election | 45.2% | 46.3% | 8.5% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 51 | 74 | 0 | 125 |

| 10 December 1977 election | 39.7% | 48.1% | 12.2% | 45.4% | 54.6% | 38 | 86 | 0 | 124 |

| 13 December 1975 election | 42.8% | 53.1% | 4.1% | 44.3% | 55.7% | 36 | 91 | 0 | 127 |

| 18 May 1974 election | 49.3% | 44.9% | 5.8% | 51.7% | 48.3% | 66 | 61 | 0 | 127 |

| 2 December 1972 election | 49.6% | 41.5% | 8.9% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 67 | 58 | 0 | 125 |

| 25 October 1969 election | 47.0% | 43.3% | 9.7% | 50.2% | 49.8% | 59 | 66 | 0 | 125 |

| 26 November 1966 election | 40.0% | 50.0% | 10.0% | 43.1% | 56.9% | 41 | 82 | 1 | 124 |

| 30 November 1963 election | 45.5% | 46.0% | 8.5% | 47.4% | 52.6% | 50 | 72 | 0 | 122 |

| 9 December 1961 election | 47.9% | 42.1% | 10.0% | 50.5% | 49.5% | 60 | 62 | 0 | 122 |

| 22 November 1958 election | 42.8% | 46.6% | 10.6% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 45 | 77 | 0 | 122 |

| 10 December 1955 election | 44.6% | 47.6% | 7.8% | 45.8% | 54.2% | 47 | 75 | 0 | 122 |

| 29 May 1954 election | 50.0% | 46.8% | 3.2% | 50.7% | 49.3% | 57 | 64 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 April 1951 election | 47.6% | 50.3% | 2.1% | 49.3% | 50.7% | 52 | 69 | 0 | 121 |

| 10 December 1949 election | 46.0% | 50.3% | 3.7% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 47 | 74 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 September 1946 election | 49.7% | 39.3% | 11.0% | 54.1% | 45.9% | 43 | 26 | 5 | 74 |

| 21 August 1943 election | 49.9% | 23.0% | 27.1% | 58.2% | 41.8% | 49 | 19 | 6 | 74 |

| 21 September 1940 election | 40.2% | 43.9% | 15.9% | 50.3% | 49.7% | 32 | 36 | 6 | 74 |

| 23 October 1937 election | 43.2% | 49.3% | 7.5% | 49.4% | 50.6% | 29 | 44 | 2 | 74 |

| 15 September 1934 election | 26.8% | 45.6% | 27.6% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 18 | 42 | 14 | 74 |

| 19 December 1931 election | 27.1% | 48.4% | 24.5% | 41.5% | 58.5% | 14 | 50 | 11 | 75 |

| 12 October 1929 election | 48.8% | 44.2% | 7.0% | 56.7% | 43.3% | 46 | 24 | 5 | 75 |

| 17 November 1928 election | 44.6% | 49.6% | 5.8% | 48.4% | 51.6% | 31 | 42 | 2 | 75 |

| 14 November 1925 election | 45.0% | 53.2% | 1.8% | 46.2% | 53.8% | 23 | 50 | 2 | 75 |

| 16 December 1922 election | 42.3% | 47.8% | 9.9% | 48.8% | 51.2% | 29 | 40 | 6 | 75 |

| 13 December 1919 election | 42.5% | 54.3% | 3.2% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 25 | 38 | 2 | 75 |

| 5 May 1917 election | 43.9% | 54.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 22 | 53 | 0 | 75 |

| 5 September 1914 election | 50.9% | 47.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 42 | 32 | 1 | 75 |

| 31 May 1913 election | 48.5% | 48.9% | 2.6% | – | – | 37 | 38 | 0 | 75 |

| 13 April 1910 election | 50.0% | 45.1% | 4.9% | – | – | 42 | 31 | 2 | 75 |

| Polling conducted by Newspoll and published in The Australian. Three percent margin of error. | |||||||||

See also

- Monarchy of Australia

- Governor-General of Australia

- Prime Minister of Australia

- Cabinet of Australia

- Federal Executive Council (Australia)

- Parliament of Australia

- Australian Senate

- Australian House of Representatives

- High Court of Australia

- Australian court hierarchy

- Political donations in Australia

- Political families of Australia

- Liberal Party of Australia

- Australian Labor Party

Notes

- ↑ "Is voting compulsory?". Voting within Australia – Frequently Asked Questions. Australian Electoral Commission. 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Hardgrave, Gary (2 March 2015). "Commonwealth Day 2015". Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, Government of Australia. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- 1 2 The timing of elections is related to the dissolution or expiry of the House of Representatives, which extends for a maximum period of three years from the date of its first sitting, not the date of the election of its members. The house can be dissolved and a new election called at any time. In 12 out of 41 parliaments since Federation, more than three years have elapsed between elections. There is a complex formula for determining the date of such elections, which must satisfy section 32 of the Constitution and sections 156–8 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. These provisions do not allow an election to be held less than 33 days or more than 68 days after the dissolution of the House of Representatives. See Australian federal election, 2010 for an example of how the formula applies in practice.

- ↑ Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia: Governor-General's role at the Wayback Machine (archived 18 July 2010)

- ↑ "Pearce, Sir George Foster (1870–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Section 64 of the Australian Constitution. Strictly speaking, ministers in the Australian government may be drawn from outside parliament, but cannot remain as ministers unless they have become a member of one of the houses of parliament within three months.

- ↑ "Australian Labor- Australian Labor". Alp.org.au:6020. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Lavelle, A. The Death of Social Democracy. 2008. Ashgate Publishing.

- ↑ Daly, Margo (2003). The Rough Guide To Australia. Rough Guides Ltd. p. 397. ISBN 9781843530909.

- ↑ Penrith, Deborah (2008). Live & Work in Australia. Crimson Publishing. p. 478. ISBN 9781854584182.

- ↑ Georgia Waters. "Why Labor struggles in Queensland". Brisbanetimes.com.au. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-09-04/vote-compass-left-right-electorates/4929064

- ↑ "Australia ready for first female leader". BBC News. 25 June 2010.

- ↑ "How the west will stay won for the Coalition". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 August 2010.

- 1 2 George Megalogenis, "The Green and the Grey", Quarterly Essay, Vol. 40, 2010, p69.

- ↑ "Victoria: the left-leaning state". The Age. Melbourne. 8 August 2010.

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-09-04/vote-compass-left-right-electorates/4929064

- ↑ "Victoria not likely to lose its mantle as the state most progressive". The Age. Melbourne. 29 November 2010.

- 1 2 Megalogenis, George (23 August 2010). "Poll divides the nation into three zones". The Australian.

- ↑ George Megalogenis, "The Green and the Grey", Quarterly Essay, Vol. 40, 2010, p69.

- ↑ Clare Blumer. "Rise of the minor parties: How the 2016 election stacks up historically". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

Further reading

| Library resources about Politics of Australia |

- Robert Corcoran and Jackie Dickenson (2010), A Dictionary of Australian Politics, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW

- Department of the Senate, 'Electing Australia's Senators', Senate Briefs No. 1, 2006, retrieved July 2007

- Rodney Smith (2001), Australian Political Culture, Longman, Frenchs Forest NSW