Hazleton, Pennsylvania

| Hazleton | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Hazleton City Hall | |

| Nickname(s): The Mountain City, Mob City, The Power City | |

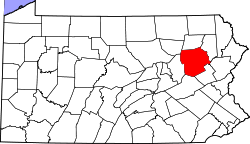

Hazleton Location within the state of Pennsylvania | |

| Coordinates: 40°57′32″N 75°58′28″W / 40.95889°N 75.97444°WCoordinates: 40°57′32″N 75°58′28″W / 40.95889°N 75.97444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Luzerne |

| Settled | 1780 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jeff Cusat (R) |

| Elevation | 1,689 ft (515 m) |

| Population (2015 Census estimate) | |

| • Total | 24,825 |

| Time zone | EST (UTC−5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) |

| ZIP codes | 18201, 18202 |

| Area code(s) | 570 Exchanges: 450, 453, 454, 455, 459 |

| FIPS code | 42-33408 |

| Website |

www |

Hazleton is a city in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 25,340 at the 2010 census. Hazleton is the 17th largest city in Pennsylvania.[1]

History

Sugarloaf Massacre

During the height of the American Revolution in the summer of 1780, British sympathizers, known as Tories, concentrated from New York's Mohawk Valley, began attacking the outposts of American revolutionaries located along the Susquehanna River Valley in Northeast Pennsylvania. Because of the reports of Tory activity in the region, Captain Daniel Klader and a platoon of 41 men from Northampton County were sent to investigate. They traveled north from the Lehigh Valley along a path known as "Warrior's Trail", which is present-day State Route 93, since this route connects the Lehigh River in Jim Thorpe (formerly known as Mauch Chunk) to the Susquehanna River in Berwick.

Heading north, Captain Klader's men made it as far north as present-day Conyngham when they were ambushed by members of the Seneca tribe and Tory militiamen. In all, 15 men were killed on September 11, 1780 in what was known the Sugarloaf Massacre.

The Moravians, a Christian denomination, had been using "Warrior's Trail" since the early 18th century after the Moravian missionary Nicolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf first used it to reach the Wyoming Valley. This particular stretch of "Warrior's Trail" had an abundance of hazel trees. Though the Moravians called the region "St. Anthony's Wilderness", it eventually became known as "Hazel Swamp", a name which had been used previously by the Indians.

The Moravian missionaries were sent from their settlements in Bethlehem to the site of the Sugarloaf Massacre to bury the dead soldiers. Because of the aesthetic natural beauty of the Conyngham Valley, some Moravians decided to stay and in 1782, built a settlement, St. Johns, along the Nescopeck Creek, which is near the present-day intersection of Interstates 80 and 81.[2]

Jacob Drumheller's Stage Stand

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the "Warrior Trail" was widened and became the Berwick Turnpike. Later, a road was built to connect Wilkes-Barre to McKeansburg. This road intersected with the Berwick Turnpike at what is present-day Broad and Vine Streets, in downtown Hazleton. An entrepreneur named Jacob Drumheller decided that this intersection was the perfect location for a rest-stop, so in 1809, he built the first building in what would be later known as Hazleton. Though a few buildings and houses began to be built nearby, the area remained a dense wilderness for about 20 more years. Aside from small-scale logging, the area offered little else. Jacob Drumheller is buried at Conyngham Union Cemetery.

Discovery of coal

Railroad developers from Philadelphia became interested in the Hazleton area once previous rumors were validated that in 1818 anthracite coal deposits had been discovered in nearby Beaver Meadows by prospectors Nathaniel Beach and Tench Coxe.

A young engineer from New York named Ariovistus "Ario" Pardee was hired to survey the topography of Beaver Meadows and report the practicality of extending a railroad from the Lehigh River Canal in Jim Thorpe to Beaver Meadows. Pardee, knowing that the area of Beaver Meadows was already controlled by Coxe and Beach, bought many acres of the land in present-day Hazleton. The investment proved to be extraordinarily lucrative. The land contained part of a massive anthracite coal field. Pardee will be forever known as the founding father of Hazleton.

Pardee incorporated the Hazleton Coal Company in 1836, the same year that the rail link to the Lehigh Valley market was about to be completed.

The Hazleton Coal Company built the first school on Church Street, where Hazleton City Hall is now located. Pardee also built the first church in Hazleton located at Church and Broad Streets. The Pardee mansion was built on the northern block of Broad Street, between present-day Church and Laurel Streets.

The coal industry attracted many immigrants for labour, mostly German and Irish in the 1840s and 1850s, and mostly Italian, Polish, Russian, Lithuanian, Slovak and Montenegrins in the 1860s to 1920s.

The coal mined in Hazleton helped to establish the United States as a world industrial power, primarily fueling the massive blast furnaces at the Bethlehem Steel Corporation.[3]

"Patch Towns"

Many small company towns, often referred to by locals as "patch towns" or "patches" surrounded Hazleton and were built by coal companies to provide housing for the miners and their families. These include:

- Beaver Meadows, coal was discovered here

- Stockton, founded by John Stockton

- Jeansville, founded by James Milens

- Milnesville, founded by James Milens

- Tresckow, formerly known as Dutchtown

- Junedale, formerly known as Colraine

- Freeland, originally called Freehold (South of South Herberton; founded by Joseph Birkbeck in 1846)

- McAdoo, originally called Pleasant Hill, then Saylors Hill

- West Hazleton, founded by Conrad Horn

- Eckley, founded by Eckley B. Coxe

- Jeddo, named after a Japanese port to which coal was exported by the Hazleton Coal Company

- Hollywood, part of Hazleton, named before Hollywood, California.

- Weatherly, small borough outside of Hazleton

Sudden prosperity and growth

Hazleton was incorporated as a borough on January 5, 1857. Its intended name was supposed to be spelled "Hazelton" but a clerk misspelled the name during incorporation, and the name "Hazleton" has been used ever since. The borough's first fire company, the Pioneer Fire Company, was organized in 1867 by soldiers returning from the American Civil War. Hazleton was incorporated as a city on December 4, 1891. The population then was estimated to be around 14,000 people.

In 1891, Hazleton became the third city in the United States to establish a city-wide electric grid.

On September 10, 1897, the Lattimer Massacre occurred near Hazleton.

Post World War II Hazleton

After World War II, the demand for coal began to decline as cleaner, more efficient fuels were being used. Readily available, cheap energy helped open the door for manufacturing. The Duplan Silk Corporation opened and became the world's largest silk mill.[4] The garment industry thrived and was invested in by New York mobster Albert Anastasia.

In 1947, Autolite Corporation was looking to expand operations in the East, and had been looking into Hazleton. Officials from Autolite came to the area to survey it and in their report, they noted Hazleton is a "mountain wilderness" with no major water route, rail route, trucking route, or airport. In response, several area leaders gathered to address these problems.

CAN-DO (Community Area New Development Organization) was formally organized in 1956 by founder Dr. Edgar L. Dessen. Their main goal was to raise money, through their "Dime A Week" campaign, in which area residents were encouraged to put a dime on their sidewalk each week to be collected by CANDO. The company raised over $250,000 and was able to purchase over 500 acres (2.0 km2) of land, which was converted into an industrial park. Because of CANDO's efforts, Hazleton was given the All-America City Award in 1964. Hazleton's economy is now based largely on manufacturing and shipping, facilitated by the relative closeness to Interstates 80 and 81.

An article published in December 2002 by U.S. News & World Report was entitled "Letter from Pennsylvania: A town in need of a tomorrow" which reported Hazleton's shortcomings to the world. It was criticized by local politicians and business leaders alike, and again prompted local leaders to address the problems facing the community.

Changing demographics and a new wave of immigrants

In 2006, Hazleton gained national attention as Republican mayor Lou Barletta and council members passed the Illegal Immigration Relief Act.[5] This ordinance was instituted to discourage hiring or renting to illegal immigrants. Initially, the ordinance levied an administrative fine on landlords for $100.00 per illegal immigrant rented to and a loss of permits for non-compliance.[6] Another act passed concurrently made English the official language of Hazleton.[7]

Mayor Lou Barletta of Hazleton estimated that as "many as half" of the estimated 10,000 Hispanics who were living in Hazleton left Hazleton when the ordinance was passed.[8] The issue was covered by the television program 60 Minutes in 2006[9] and the Fox News show The O'Reilly Factor in March 2007.[10]

The ordinance was criticized as illegal and unconstitutional. A number of residents (landlords, business owners, lawful aliens defined as illegal under the act, and unlawful aliens)[11][12][13] filed suit to strike down the law, claiming it violates the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution as well as the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. After a trial and several appeals including a remand from the Supreme Court, the Third Circuit found the ordinance invalid due to federal preemption.[14]

Geography

Hazleton is located at 40°57′32″N 75°58′28″W / 40.95889°N 75.97444°W (40.958834, −75.974546).[15]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 6.0 square miles (16 km2), all of it land.

Hazleton is located 12 miles (19 km) north of Tamaqua and 30 miles (48 km) south of Scranton/Wilkes-Barre. Located in Pennsylvania's ridge and valley section on a plateau named Spring Mountain, Hazleton's highest elevation is 1886 feet above sea level, one of the highest incorporated cities east of the Mississippi River and the highest incorporated city in Pennsylvania. It straddles the divide between the Delaware and Susquehanna River watersheds.

Greater Hazleton

Hazleton and its surrounding communities are collectively known as Greater Hazleton. Greater Hazleton encompasses an area located within three counties: southern Luzerne County, northern Schuylkill County, and northern Carbon County. The population of Greater Hazleton was 77,187[16] at the 2010 census. Greater Hazleton includes the City of Hazleton; the boroughs of Beaver Meadows, Conyngham, Freeland, Jeddo, McAdoo, Weatherly, West Hazleton, White Haven; the townships of Black Creek, Butler, East Union, Kline, Foster, Hazle, Rush, Sugarloaf; and the towns, villages, or CDPs of Audenried, Coxes Villages, Drifton, Drums, Ebervale, Eckley, Fern Glen, Haddock, Harleigh, Harwood Mines, Hazle Brook, Highland, Hollywood, Hometown, Hudsondale, Humboldt Village, Humboldt Industrial Park, Japan, Jeansville, Junedale, Kelayres, Kis-Lyn, Lattimer, Milnesville, Nuremberg, Oneida, Pardeesville, Quakake, St. Johns, Sandy Run, Still Creek, Stockton, Sybertsville, Ringtown, Sheppton, Tomhicken, Tresckow, Upper Lehigh, Weston, and Zion Grove.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,080 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,707 | −17.9% | |

| 1870 | 4,317 | 152.9% | |

| 1880 | 6,935 | 60.6% | |

| 1890 | 11,872 | 71.2% | |

| 1900 | 14,230 | 19.9% | |

| 1910 | 25,452 | 78.9% | |

| 1920 | 32,277 | 26.8% | |

| 1930 | 36,765 | 13.9% | |

| 1940 | 38,009 | 3.4% | |

| 1950 | 35,491 | −6.6% | |

| 1960 | 32,056 | −9.7% | |

| 1970 | 30,426 | −5.1% | |

| 1980 | 27,318 | −10.2% | |

| 1990 | 24,730 | −9.5% | |

| 2000 | 23,329 | −5.7% | |

| 2010 | 25,340 | 8.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 24,825 | [17] | −2.0% |

| Sources:[18][19][20][21] | |||

2000 census

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 21,340 people, 9,281 households, and 6,004 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,904.6 people per square mile (1,508.8/km2). There were 10,556 housing units at an average density of 1,934.1 per square mile (747.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.7% White, 0.82% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.65% Asian, 16.4% Pacific Islander, 2.76% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.15% of the population.

There were 10,281 households, out of which 24.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.1% were married couples living together, 13.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.6% were non-families. 37.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 19.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city the population was spread out, with 21.0% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 22.2% from 45 to 64, and 22.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females there were 87.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $38,082, and the median income for a family was $57,093. Males had a median income of $36,144 versus $37,926 for females. The per capita income for the city was $39,270. About 9.4% of families and 4.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.4% of those under age 18 and 6.6% of those age 65 or over.

According to the 2015 census,[22] the top ten ancestries in the city are: Italian (72.8%), Polish (43.2%), German (23.9%), Irish (14.1%), Slovak (11.4%), American (5.5%), English (3.4%), Ukrainian (2.8%), Greek (2.2%), and Russian (1.5%).

2010 census

As of the 2010 census,[23] the racial makeup of the city was 69.4% White (59.0% non-Hispanic/Latino white), 4.0% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.8% Asian, and 22.0% from other races, and 3.4% were multiracial. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 37.3% of the population.

There were 23,340 people, 9,798 households, with 6,162 of these being family households. The population density was 4,123.3 people per square mile (1583.75/km2). There were 9,409 housing units, at an average density of 1901.5 per square mile (713.1/km2).

There were 9,798 households, out of which 22.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.9% were married couples living together, 19.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.1% were non-family households. 21.9% were made up of individuals and 15.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.19.

In the city the population was spread out, with 25.3% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 24.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.4 males.

Hispanic and Latino community

As of 2015 Hazleton is among the Pennsylvania cities with the highest Hispanic and Latino populations since about 40% of Hazleton's population was Hispanic or Latino.[24]

In 2000 4.9% of the city population was Hispanic and Latino.[25] Almost all of the population growth in Hazleton from 2000 to 2010 consisted of Hispanics and Latinos, and the city would have lost population if the Hispanics and Latinos did not come. Hazleton was about 37% Hispanic/Latino as of 2010.[26] Over half of Hazleton's Hispanic population is of Dominican descent, making up 21% in 2010, Hazleton has the highest percentage of Dominicans in Pennsylvania and the 4th highest in the nation.

Many Dominicans had moved to Hazleton from portions of New York City, including the Bronx and Brooklyn; and parts of northern New Jersey, such as Newark and Paterson.[26] Many of these migrants had families that were relatively large.[25] Amilcar Arroyo, a Hazleton Integration Project board member, stated in 2012 that he estimated that 80% of Hazleton's Hispanics and Latinos are of Dominican origins, and that many of them had ancestry from San José de Ocoa.[26]

Many Hispanic and Latino businesses are on Wyoming Street.[26] In 2016 Michael Matza of the Philadelphia Inquirer stated that as a result of the influx of Hispanics the Wyoming Street corridor was revived from a moribund state.[25]

El Mensajero, a monthly publication, serves as the Hispanic/Latino newspaper of Hazleton. Each issue is 56 pages.[25]

Economy

All of Hazleton's major mining and garment industries have disappeared over the past 50 years. Through the efforts of CANDO and a practical highway infrastructure, Hazle Township's Humboldt Industrial Park has become home to many industries. Coca-Cola, American Eagle Outfitters, Hershey, Office Max, Simmons Bedding Company, Michaels, Network Solutions, AutoZone, General Mills, Steelcase, WEIR Minerals, EB Brands and Amazon.com[27] are just some of the large companies with distribution, manufacturing, or logistic operations in Hazleton.

6.7% of Residents had an income below the poverty level as compared to a statewide average of 12.5% in 2010[28]

Notable people

- Lou Barletta, congressman representing the 11th District of Pennsylvania

- Hubie Brown, basketball coach and television analyst

- Russ Canzler, Major League Baseball player in the New York Yankees minor league organization.

- Flick Colby, choreographer

- Carl Duser, baseball player

- Todd A. Eachus, former state representative of the 116th District and House majority leader of Pennsylvania

- Thomas R. Kline, lawyer

- Sarah Knauss, lived to age 119

- Norm Larker (Beaver Meadows), National League All-Star player for the LA Dodgers

- Sherrie Levine, photographer and appropriation artist

- Joe Maddon, manager of Major League Baseball's Chicago Cubs

- Tom Matchick, MLB player for the Detroit Tigers, Boston Red Sox, Kansas City Royals, Milwaukee Brewers, Baltimore Orioles

- Rick Mikula, author, lecturer, naturalist

- Judith Nathan, wife of former New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani

- Jack Palance (Hazle Township), Oscar-winning actor

- Andrew Soltis, Chess Grandmaster

- John Thomas Sweeney, murderer of Dominique Dunne, was born and raised in Hazleton

- Mike Tresh, MLB catcher

- Bob Tucker, NFL tight end with the New York Giants

Local media

Newspapers

- The Standard-Speaker (ISO 4: Stand.-Speak.), daily newspaper, name merged from the Standard Sentinel (morning paper) and Plain Speaker (evening paper)

- Poder Latino, Monthly Hispanic newspaper covering Northeast Pennsylvania. www.poderlatinonews.com

- The Hazleton Headlines, online-based newspaper, serving Hazleton and the surrounding area with local news & nearby happenings. www.HazletonHeadlines.com[29]

Radio

- WAZL-AM at 1490 & on 94.5 FM on dial has been on-the-air since 1932.

Television

- Sam-Son Productions (Public-access television)[30]

- WYLN-35 Broadcast Channel 35 and Service Electric Cablevision cable channel 7[31]

Education

The first school was built in the 1830s by the Hazleton Coal Company. It was a private elementary school at the corner of Church and Green Streets, the present-day site of Hazleton City Hall. Hazleton High School, the first high school, was built in 1875 at Pine and Hemlock Streets, the present-day site of the Pine Street Playground. Bishop Hafey High School, the Vikings, was Hazleton's only Roman Catholic High School, owned by the Diocese of Scranton. It was opened in 1971 and closed in 2007 by the order of former Bishop Joseph F. Martino.

Hazleton Area School District

The Hazleton Area School District (HASD) operates public schools serving the city limits. There are three schools in Hazleton operated by the HASD:[32]

- Hazleton Elementary / Middle School

- Heights-Terrace Elementary / Middle School

- Arthur Street Elementary School

All district students are zoned to Hazleton Area High School in Hazle Township.

Private schools

- MMI Preparatory School, the Preppers

- Holy Family Academy, the Golden Eagles (located at the former St. Joseph's Memorial School). The school is owned by the Diocese of Scranton.

- Immanuel Christian School, the Lions

Colleges and universities

- Penn State Hazleton

- Lackawanna College

- Luzerne County Community College

- McCann School of Business and Technology

Government

Mayor

- Mayor Jeff Cusat, Republican (2015)

City Council

- Jack Mundie, (Dem) President

- Jean Mope, (Dem) Vice President

- Dave Sosar (Dem)

- Grace Cuozzo (Dem)

- Robert Gavio (Dem)

Transportation infrastructure

Air transit

Hazleton's commercial passenger airport is the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International Airport located in Avoca, Pennsylvania. The Lehigh Valley International Airport also serves Greater Hazleton. The Hazleton Municipal Airport is the general aviation airport for the city.

Public transportation

Public transportation is provided by the Hazleton Public Transit, a service of the City of Hazleton's Department of Public Services. HPT operates nine routes throughout the city and neighboring communities.

Rail

While Hazleton currently has no passenger rail service, it is a major regional center for commercial rail traffic, operated by Norfolk Southern Railway.

Roads

Three Interstate highways run outside the Hazleton area, with associated exits to the city.

- Interstate 81, which runs from Dandridge, Tennessee in the south, to Wellesley Island, New York in the north.

- Interstate 80, which runs from San Francisco, California in the west, to Fort Lee, New Jersey in the east.

- Interstate 476, the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, which runs from Chester to Clarks Summit, near Scranton.

There are five major inbound arteries into Hazleton: Church Street, Broad Street, CAN-DO Expressway, Arthur Gardner Parkway, 22nd Street.

Museums and organizations

- Eckley Miners' Village

- The Greater Hazleton Historical Society and Museum[33]

- The Hazleton Area Public Library

- The MPB Community Players

- The Nuremberg Community Players

- The Pennsylvania Theatre of Performing Arts (PTPA)

Parks and recreation

Annual festivals

Hazleton's annual street festival, Funfest, is celebrated usually during the second weekend of September. The festival includes a craft show, a car show, entertainment from local bands, and many games of chance. The Funfest parade is held on Sunday during the Funfest weekend. Valley Day is celebrated in Conyngham during the first weekend of August. Many church festivals, including the Festival of the Madonna del Monte at Most Precious Blood Roman Catholic Church in Hazleton, is celebrated to preserve the Italian heritage of Hazleton. This is honored by carrying candle houses (cintis) by men up and down the streets of the eastern side of town, from the church to the Key Club, which is located on Monges Street.

Regional parks and outdoor entertainment

- Altmiller Playground

- Hazle Township Community Park & Soccer Fields

- Eagle Rock Resort (private)

- Edgewood In The Pines Golf Course

- Greater Hazleton Rails To Trails

- Hickory Run State Park

- Lehigh Gorge State Park

- Paragon Off-Road Adventure Park

- Valley Country Club Golf Course (private)

- Whitewater Challenge, in Jim Thorpe

Sports

Hazleton was a long-time home to minor baseball. On April 14, 1934, the Philadelphia Phillies entered into an affiliation agreement with the New York–Penn League Hazleton Mountaineers. This was the first ever minor league affiliation for the Phillies.[34] The last minor-league club to play in Hazleton was the Hazleton Dodgers in 1950, a Brooklyn Dodgers farm-club which played in the Class D North Atlantic League.[35]

Landmarks and historic locations

Hazleton's modest skyline is remarkable for a city its size. Almost unaffected by examples of modern architecture, it provides an interesting window on American urbanism prior to World War II.

- Eckley Miners' Village, Eckley, Pennsylvania

- Hazleton Elementary / Middle School (former Hazleton Senior High School)

- Our Lady of Mount Carmel Tyrolean Roman Catholic Church, the only Tyrolean church in the United States (now closed)

- St. Gabriel's Catholic Parish Complex, 122 South Wyoming Street, Hazleton

- Saint Joseph Slovak Roman Catholic Church, 604 North Laurel Street, the first Slovak Roman Catholic church established in the Western Hemisphere

- The Altamont Hotel

- The Duplan Silk Building

- The Hazleton Cemetery (the Vine Street Cemetery)

- The Hazleton National Bank

- Markle Banking & Trust Company Building, tallest building in Hazleton

- The Traders Bank Building

- Israel Platt Pardee Mansion

- The march of the Lattimer Massacre, which began at State Route 924 near Harwood

Sister cities

Hazleton has several sister cities. They are:

-

– Gorzów Wielkopolski, Lubuskie, Poland

– Gorzów Wielkopolski, Lubuskie, Poland -

– Donegal, Limerick, Bangor, Coleraine, Dublin, Belfast, Letterkenny, Ireland

– Donegal, Limerick, Bangor, Coleraine, Dublin, Belfast, Letterkenny, Ireland -

– Italy and the Communities of Sicilia Italy – Corleone, Palermo, Catrone, Catania, Cilento, Florence, Bellagio, Positano, Naples, Venezia, Capri, Lambro, Mingardo, Campania, Italy

– Italy and the Communities of Sicilia Italy – Corleone, Palermo, Catrone, Catania, Cilento, Florence, Bellagio, Positano, Naples, Venezia, Capri, Lambro, Mingardo, Campania, Italy -

– see link for name places in the USA[36]

– see link for name places in the USA[36]

Climate

The Köppen climate classification subtype for this climate is "Dfb" (Cool Summer Continental Climate).[37]

| Climate data for Hazleton, Pennsylvania | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1 (30) |

1 (33) |

5 (41) |

12 (54) |

18 (65) |

22 (72) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

7 (45) |

1 (34) |

12 (54) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −11 (13) |

−9 (15) |

−5 (23) |

1 (34) |

7 (44) |

11 (52) |

14 (58) |

13 (56) |

9 (49) |

3 (38) |

−2 (29) |

−8 (18) |

2 (36) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81 (3.2) |

71 (2.8) |

86 (3.4) |

100 (4) |

117 (4.6) |

130 (5) |

112 (4.4) |

114 (4.5) |

130 (5) |

97 (3.8) |

100 (4) |

81 (3.2) |

1,217 (47.9) |

| Source: Weatherbase[38] | |||||||||||||

References

- ↑ "Census 2015: Pennsylvania – USATODAY.com". USA TODAY News.

- ↑ Greater Hazleton Historical Society

- ↑ Greater Hazleton Historical Society

- ↑ Greater Hazleton Historical Society

- ↑ Text of the ordinances

- ↑ Illegal Immigration Relief Act passed | Small Town Defenders – Hazleton, Pennsylvania

- ↑ "2006-19 Official English" (PDF). smalltowndefenders.com.

- ↑ "Towns take a local approach to blocking illegal aliens". Washington Times. 2006-09-21.

- ↑ "Welcome To Hazleton". CBS News. November 17, 2006.

- ↑ BillOReilly.com: The O'Reilly Factor Flash

- ↑ "Initial Complaint" (PDF). aclupa.org.

- ↑ "First Amended Complaint" (PDF). aclupa.org.

- ↑ "Second Amended Complaint" (PDF). aclupa.org.

- ↑ "Lozano v. City of Hazleton (3rd Cir. 2013)" (PDF). ca3.uscourts.gov.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Population

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Number of Inhabitants: Pennsylvania" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ "DP-1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". QuickFacts Hazleton city, Pennsylvania. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Klibanoff, Eleanor. "The Immigrants It Once Shut Out Bring New Life To Pennsylvania Town." National Public Radio. October 14, 2015. Retrieved on July 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Matza, Michael. "10 years after immigration disputes, Hazleton is a different place." Philadelphia Inquirer. April 4, 2016. Retrieved on July 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Frantz, Jeff. "Not all in Hazleton conviced old town, new immigrants can co-exist happily." Pennlive. June 10, 2012. Retrieved on July 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon to Locate New Distribution Center in Hazleton, Pennsylvania". Reuters. May 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Hazleton, Pennsylvania (PA) poverty rate data – information about poor and low income residents living in this city". city-data.com.

- ↑ http://www.HazletonHeadlines.com www.Facebook.com/HazletonHeadlines

- ↑ "SSPTV.com – Hazleton PA – Official Site of FYI News 13 Hazleton PA". ssptv.com.

- ↑ http://www.wylntv.com/

- ↑ "Locate Us." Hazleton Area School District. Retrieved on July 18, 2016.

- ↑ http://hazletonmuseum.org/

- ↑ "Hazelton to Be Phils' Farm" (PDF). New York Times. 1934-04-15. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ "Hazleton, Pennsylvania". BR Bullpen. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ http://mysite.verizon.net/vze8isfi/hazleton.html

- ↑ "Hazleton, Pennsylvania Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ↑ "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2013. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hazleton, Pennsylvania. |