Lumpenproletariat

| Part of a series on |

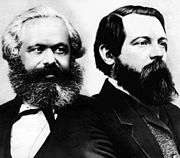

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

|

Lumpenproletariat is a term that was originally coined by Karl Marx to describe the layer of the working class that is unlikely ever to achieve class consciousness and is therefore lost to socially useful production, of no use to the revolutionary struggle, and perhaps even an impediment to the realization of a classless society.[1] The word is derived from the German word Lumpenproletarier, "Lumpen" literally meaning "miscreant" as well as "rag". The Marxist Internet Archive writes that "[lumpenproletariat] identifies the class of outcast, degenerated and submerged elements that make up a section of the population of industrial centers" which include "beggars, prostitutes, gangsters, racketeers, swindlers, petty criminals, tramps, chronic unemployed or unemployables, persons who have been cast out by industry, and all sorts of declassed, degraded or degenerated elements."[2]

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), Marx gives this description of the lumpenproletariat:

- Alongside decayed roués with dubious means of subsistence and of dubious origin, alongside ruined and adventurous offshoots of the bourgeoisie, were vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux [pimps], brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars—in short, the whole indefinite, disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French call la bohème.[3]

In the Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx rhetorically describes the lumpenproletariat as a "class fraction" that constituted the political power base for Louis Bonaparte of France in 1848. In this sense, Marx argued that Bonaparte was able to place himself above the two main classes, the proletariat and bourgeoisie, by resorting to the "lumpenproletariat" as an apparently independent base of power, while in fact advancing the material interests of the "finance aristocracy".

For rhetorical purposes, Marx identifies Louis Napoleon himself as being like a member of the lumpenproletariat insofar as, being a member of the finance aristocracy, he has no direct interest in productive enterprises.[4] This is a rhetorical flourish, however, which equates the lumpenproletariat, the rentier class, and the apex of class society as equivalent members of the class of those with no role in useful production.

Conceptions and reception

Anarchist and late 20th-century perspectives

The influential 19th-century anarchist activist and theorist Mikhail Bakunin had a view almost opposite of Marx's on the revolutionary potential of the lumpenproletariat vs. the proletariat.[5] Bakunin, according to Nicholas Thoburn, "considers workers' integration in capital as destructive of more primary revolutionary forces. For Bakunin, the revolutionary archetype is found in a peasant milieu (which is presented as having longstanding insurrectionary traditions, as well as a communist archetype in its current social form – the peasant commune) and amongst educated unemployed youth, assorted marginals from all classes, brigands, robbers, the impoverished masses, and those on the margins of society who have escaped, been excluded from, or not yet subsumed in the discipline of emerging industrial work ... in short, all those whom Marx sought to include in the category of the lumpenproletariat".[6]

Bakunin elaborated on his critical perspective in his 1872 work On the International Workingmen's Association and Karl Marx:

To me the flower of the proletariat is not, as it is to the Marxists, the upper layer, the aristocracy of labor, those who are the most cultured, who earn more and live more comfortably than all the other workers. Precisely this semi-bourgeois layer of workers would, if the Marxists had their way, constitute their fourth governing class. This could indeed happen if the great mass of the proletariat does not guard against it. By virtue of its relative. well-being and semi-bourgeois position, this upper layer of workers is unfortunately only too deeply saturated with all the political and social prejudices and all the narrow aspirations and pretensions of the bourgeoisie. Of all the proletariat, this upper layer is the least social and the most individualist.

By the flower of the proletariat, I mean above all that great mass, those millions of the uncultivated, the disinherited, the miserable, the illiterates, whom Messrs. Engels and Marx would subject to their paternal rule by a strong government – naturally for the people’s own salvation! All governments are supposedly established only to look after the welfare of the masses! By flower of the proletariat, I mean precisely that eternal “meat” (on which governments thrive), that great rabble of the people (underdogs, “dregs of society”) ordinarily designated by Marx and Engels in the picturesque and contemptuous phrase Lumpenproletariat. I have in mind the “riff-raff,” that “rabble” almost unpolluted by bourgeois civilization, which carries in its inner being and in its aspirations, in all the necessities and miseries of its collective life, all the seeds of the socialism of the future, and which alone is powerful enough today to inaugurate and bring to triumph the Social Revolution.

— Mikhail Bakunin, On the International Workingmen's Association and Karl Marx [7]

However, in some societies, individual members of this class of people without formal employment have, on occasion, taken the lead in issuing a progressive challenge to society. One example is Abahlali baseMjondolo in the KwaZulu region of contemporary South Africa.

The Young Lords, once a Latino street gang, believed that revolutionary change would become a reality only via a coalition between workers and the lumpenproletariat.

In the late 1960s, Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party came to believe that the lumpenproletariat could have a progressive role. Newton argued that the economic and social system of his time was fundamentally different from that which Marx based his analysis on, saying, "As the ruling circle continue to build their technocracy, more and more of the proletariat will become unemployable, become lumpen, until they have become the popular class, the revolutionary class".[8] This is the class the Black Panther Party sought to organize, he said. Some disregard Newton's interpretation, saying he applied the term to, and sought to organize, the temporarily unemployed, rather than the true lumpen. However, a careful reading of his writings reveals repeated references to the "unemployed" and "unemployable" as those with revolutionary potential.

Frantz Fanon also argued in The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that revolutionary movements in colonized countries could not exclude the lumpenproletariat, as it constitutes both a counterrevolutionary and a revolutionary potential. He described the lumpenproletariat as "one of the most spontaneous and the most radically revolutionary forces of a colonized people". However, it is an ignorant and desperate class, particularly susceptible to being co-opted by counterrevolutionary forces. Therefore, he claimed, education of the dispossessed masses should be central to revolutionary strategy.[9]

The Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) included the participation of Calcutta's criminal elements in the early 1970s. The Party saw this segment of Calcutta, largely consisting of people from marginalized upbringings, as capable of revolutionary violence. Members of this social stratum would then ideally reform themselves and become conventional revolutionaries, leaving behind anti-social activities.

Engels, Marx, Trotsky, and others

Engels wrote about the Neapolitan lumpenproletariat during the repression of the 1848 Revolution in Naples: "This action of the Neapolitan lumpenproletariat decided the defeat of the revolution. Swiss guardsmen, Neapolitan soldiers and lazzaroni combined pounced upon the defenders of the barricades".[10]

In other writings, Marx also saw little potential in these sections of society. About rebellious mercenaries, he wrote: "A motley crew of mutineering soldiers who have murdered their officers, torn asunder the ties of discipline, and not succeeded in discovering a man on whom to bestow supreme command are certainly the body least likely to organise a serious and protracted resistance".[11]

Marx's description of mutineers as being unreliable could be questioned. Russian Army mutineers and their soldiers' committees were critical to the overturning of the Tsarist regime during the Russian Revolution of 1917. Yet, there is a difference in that the Russian Revolution was a general uprising of most of Russia's popular classes, not just a military mutiny.[12] Also, the Russian Imperial Army was a regular army of conscripts,[13] not an army of mercenaries; as such, its social extraction was quite different, and much closer to the peasantry than to the lumpenproletariat.[14]

According to Marx, the lumpenproletariat had no special motive for participating in revolution, and might in fact have an interest in preserving the current class structure, because the members of the lumpenproletariat usually depend on the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy for their day-to-day existence. In that sense, Marx saw the lumpenproletariat as a counter-revolutionary force.[15]

Leon Trotsky elaborated this view, perceiving the lumpenproletariat as especially vulnerable to reactionary thought. In his collection of essays Fascism: What it is and how to fight it, he describes Benito Mussolini's capture of power: "Through the fascist agency, capitalism sets in motion the masses of the crazed petty bourgeoisie and the bands of declassed and demoralized lumpenproletariat – all the countless human beings whom finance capital itself has brought to desperation and frenzy".[16]

Marx's definition has influenced contemporary sociologists, who are concerned with many of the marginalized elements of society characterized by Marx under this label. Marxian and even some non-Marxist sociologists now use the term to refer to those they see as the "victims" of modern society, who exist outside the wage-labor system, such as beggars, or people who make their living through disreputable means: prostitutes and pimps, swindlers, carnies, drug dealers, bootleggers, and bookmakers, but depend on the formal economy for their day-to-day existence.

In modern social theory sometimes the word underclass is used as equivalent to Marx' lumpenproletariat.[17] In a May 14, 2012 article on Truthdig titled 'Colonized by Corporations', Chris Hedges brought back this concept, writing that

- "The danger the corporate state faces does not come from the poor. The poor, those Karl Marx dismissed as the Lumpenproletariat, do not mount revolutions, although they join them and often become cannon fodder. The real danger to the elite comes from déclassé intellectuals, those educated middle-class men and women who are barred by a calcified system from advancement. Artists without studios or theaters, teachers without classrooms, lawyers without clients, doctors without patients and journalists without newspapers descend economically. They become, as they mingle with the underclass, a bridge between the worlds of the elite and the oppressed. And they are the dynamite that triggers revolt."[18]

Used as a pejorative

In modern Bengali, Bulgarian, English,[19] Estonian,[20] Greek, Hungarian, Japanese, Korean, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian,[21] Spanish, and Turkish,[22] lumpen, the shortened form of lumpenproletariat, is used to refer to lower classes of society.

See also

- Black Market

- Informal sector

- Lumpenbourgeoisie

- Marginalization

- Naples Lazzaroni

- Sans-culottes

- Underclass

- Precariat

- Frantz Fanon

Notes

- ↑ "The Model Republic". Marx/Engels Archive.

- ↑ "Glossary of Terms: Lumpenproletariat". MIA: Encyclopedia of Marxism.

- ↑ "The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. 1852, Chp. V". Marx/Engels Archive.

- ↑ Hayes, P. (1993) 'Marx's Analysis of the French Class Structure', Theory and Society, 22: 99–123.

- ↑ "Both agreed that the proletariat would play a key role, but for Marx the proletariat was the exclusive, leading revolutionary agent while Bakunin entertained the possibility that the peasants and even the lumpenproletariat (the unemployed, common criminals, etc.) could rise to the occasion."Marxism and Anarchism: The Philosophical Roots of the Marx-Bakunin Conflict – Part Two" by Ann Robertson.

- ↑ Nicholas Thoburn. "The lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnameable" in Deleuze, Marx and Politics

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/works/1872/karl-marx.htm

- ↑ Garrett Epps, "Huey Newton Speaks at Boston College, Presents Theory of 'Intercommunalism,'" The Harvard Crimson,November 19, 1970.

- ↑ Sartre, Frantz Fanon ; translated from the French by Richard Philcox ; with commentary by Jean-Paul; Bhabha, Homi K. (2004). The Wretched of the Earth / Frantz Fanon ; translated from the French by Richard Philcox ; introductions by Jean-Paul Sartre and Homi K. Bhabha. ([Nachdr.] ed.). New York: Grove Press. pp. 81–88. ISBN 9780802141323.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels (May 31, 1848). The Latest Heroic Deed of the House of Bourbon. Marx/Engels Collected Works. vol. 7. Marxists Internet Archive. p. 24.

- ↑ Karl Marx; Friedrich Engels (1960). The first Indian war of Independence 1855–59. Moscow: Foreign Languages Pub. House. p. 42.

- ↑ Reed, John. Ten Days That Shook the World.

- ↑ "Joshua A. Sanborn. Drafting the Russian Nation: Military Conscription, Total War, and Mass Politics, 1905-1925: Review". H-Net Reviews.

- ↑ "The Russian Empire Before 1914". History Man Web Site.

- ↑ "Manifesto of the Communist Party". Marx-Engels Archive.

The "dangerous class", [lumpenproletariat] the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society, may, here and there, be swept into the movement by a proletarian revolution; its conditions of life, however, prepare it far more for the part of a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky (1932). "How Mussolini triumphed". What Next? Vital Question for the German Proletariat. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Lawson, Bill E. (1992). The Underclass question. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-922-8.

- ↑ Chris Hedges (2012). "Colonized by Corporations". Truthdig.

- ↑ http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/lumpen

- ↑ "Õigekeelsussõnaraamat (2006)" (in Estonian). Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ↑ "Over 30 000 children get lost in Russia annually". Pravda. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ↑ "Sözlerle ilgili sorular" (in Turkish). Turkish Language Association. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

Further reading

- Eric Hobsbawm (2002). Bandits. London: New Press.

- Friedrich Engels (1999). Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. Oxford Paperbacks.

- Nicholas Thoburn (2002). Difference in Marx: The Lumpenproletariat and the Proletarian Unnamable. in Economy and Society Vol. 31, No. 3.