History of Tibet

Tibetan history, as it has been recorded, is particularly focused on the history of Buddhism in Tibet. This is partly due to the pivotal role this religion has played in the development of Tibetan and Mongol cultures and partly because almost all native historians of the country were Buddhist monks.

Geographical setting

Tibet lies between the core areas of the ancient civilizations of China and of India. Extensive mountain ranges to the east of the Tibetan Plateau mark the border with China, and the towering Himalayas of Nepal and India form a barrier between Tibet and India. Tibet is nicknamed "the roof of the world" or "the land of snows".

Linguists classify the Tibetan language and its dialects as belonging to the Tibeto-Burman languages, the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family.

Prehistory

Some archaeological data suggests archaic humans may have passed through Tibet at the time India was first inhabited, half a million years ago.[1] Modern humans first inhabited the Tibetan Plateau at least twenty-one thousand years ago.[2] This population was largely replaced around 3,000 BC by Neolithic immigrants from northern China. However, there is a "partial genetic continuity between the Paleolithic inhabitants and the contemporary Tibetan populations".[2]

Megalithic monuments dot the Tibetan Plateau and may have been used in ancestor worship.[3] Prehistoric Iron Age hill forts and burial complexes have recently been found on the Tibetan Plateau but the remote high altitude location makes archaeological research difficult.

Zhang Zhung kingdom

According to Namkhai Norbu some Tibetan historical texts identify the Zhang Zhung culture as a people who migrated from the Amdo region into what is now the region of Guge in western Tibet.[4] Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the Bön religion.[3] By the 1st century BC, a neighboring kingdom arose in the Yarlung Valley, and the Yarlung king, Drigum Tsenpo, attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's Bön priests from Yarlung.[5] He was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century.

In A.D. 108, "the K'iang or Tibetans, who were then entirely savage and lived a nomadic life west and south of the Koko-nor, attacked the Chinese posts of Kansu, threatening to cut the Tunhwang road. Liang K'in, at the price of some fierce fighting, held them off." Similar incursions were repelled in A.D. 168-169 by the Chinese general Tuan Kung.[6]

Mythological origins

The dates attributed to the first Tibetan king, Nyatri Tsenpo (Wylie: Gnya'-khri-btsan-po ), vary. Some Tibetan texts give 126 BC, others 414 BC.[7] Nyatri Tsenpo is said to have descended from a one-footed creature called the Theurang, having webbed fingers and a tongue so large it could cover his face. Due to his terrifying appearance he was feared in his native Puwo and exiled by the Bön to Tibet. There he was greeted as a fearsome being, and he became king.[4]

The Tibetan kings were said to remain connected to the heavens via a dmu cord (dmu thag) so that rather than dying, they ascended directly to heaven, when their sons achieved their majority.[8] According to various accounts, king Drigum Tsenpo (Dri-gum-brtsan-po) either challenged his clan heads to a fight,[9] or provoked his groom Longam (Lo-ngam) into a duel. During the fight the king's dmu cord was cut, and he was killed. Thereafter Drigum Tsenpo and subsequent kings left corpses and the Bön conducted funerary rites.[5][10][11]

In a later myth, first attested in the Maṇi bka' 'bum, the Tibetan people are the progeny of the union of the monkey Pha Trelgen Changchup Sempa and rock ogress Ma Drag Sinmo. But the monkey was a manifestation of the bodhisattva Chenresig, or Avalokiteśvara (Tib. Spyan-ras-gzigs) while the ogress in turn incarnated Chenresig's consort Dolma (Tib. 'Grol-ma).[12][13]

Yarlung Dynasty

From the 7th century AD Chinese historians referred to Tibet as Tubo (吐蕃), though four distinct characters were used. The first externally confirmed contact with the Tibetan kingdom in recorded Tibetan history occurred when King Namri Löntsän (Gnam-ri-slon-rtsan) sent an ambassador to China in the early 7th century.[14]

.png)

Tibetan Empire

The power that became the Tibetan state originated when a group convinced Stag-bu snya-gzigs [Tagbu Nyazig] to rebel against Dgu-gri Zing-po-rje [Gudri Zingpoje], who was in turn a vassal of the Zhang-zhung empire under the Lig myi dynasty. The group prevailed against Zing-po-rje. At this point Namri Songtsen (Namri Löntsän) was the leader of a clan which prevailed over all his neighboring clans, one by one, and he gained control of all the area around what is now Lhasa by 630, when he was assassinated. This new-born regional state would later become known as the Tibetan Empire. The government of Namri Songtsen sent two embassies to China in 608 and 609, marking the appearance of Tibet on the international scene.[15][16]

Traditional Tibetan history preserves a lengthy list of rulers whose exploits become subject to external verification in the Chinese histories by the 7th century. From the 7th to the 11th century a series of emperors ruled Tibet – see List of emperors of Tibet - of whom the three most important in later religious tradition were Songtsän Gampo, Trisong Detsen and Ralpacan, "the three religious kings" (mes-dbon gsum), who were assimilated to the three protectors (rigs-gsum mgon-po), respectively Avalokiteśvara, Mañjuśrī and Vajrapāni. Throughout the centuries from the time of the emperor the power of the empire gradually increased over a diverse terrain so that by the reign of the emperor in the opening years of the 9th century, its influence extended as far south as Bengal and as far north as Mongolia.

The varied terrain of the empire and the difficulty of transportation, coupled with the new ideas that came into the empire as a result of its expansion, helped to create stresses and power blocs that were often in competition with the ruler at the center of the empire. Thus, for example, adherents of the Bön religion and the supporters of the ancient noble families gradually came to find themselves in competition with the recently introduced Buddhism.

Era of Fragmentation

The Era of Fragmentation is a period of Tibetan history between the 9th and 11th centuries. During this era, the political centralization of the earlier Tibetan Empire collapsed.[17] The period was dominated by rebellions against the remnants of imperial Tibet and the rise of regional warlords.[18] Upon the death of Langdarma, the last emperor of a unified Tibetan empire, there was a controversy over whether he would be succeeded by his alleged heir Yumtän (Yum brtan), or by another son (or nephew) Ösung (’Od-srung) (either 843–905 or 847–885). A civil war ensued, which effectively ended centralized Tibetan administration until the Sa-skya period. Ösung's allies managed to keep control of Lhasa, and Yumtän was forced to go to Yalung, where he established a separate line of kings.[19] In 910, the tombs of the emperors were defiled.

The son of Ösung was Pälkhortsän (Dpal 'khor brtsan) (865–895 or 893–923). The latter apparently maintained control over much of central Tibet for a time, and sired two sons, Trashi Tsentsän (Bkra shis brtsen brtsan) and Thrikhyiding (Khri khyi lding), also called Kyide Nyigön (Skyid lde nyi ma mgon) in some sources. Thrikhyiding migrated to the western Tibetan region of upper Ngari (Stod Mnga ris) and married a woman of high central Tibetan nobility, with whom he founded a local dynasty.[20]

After the breakup of the Tibetan empire in 842, Nyima-Gon, a representative of the ancient Tibetan royal house, founded the first Ladakh dynasty. Nyima-Gon's kingdom had its centre well to the east of present-day Ladakh. Kyide Nyigön's eldest son became ruler of the Mar-yul Ladakh region, and his two younger sons ruled western Tibet, founding the Kingdom of Guge and Pu-hrang. At a later period the king of Guge's eldest son, Kor-re, also called Jangchub Yeshe-Ö (Byang Chub Ye shes' Od), became a Buddhist monk. He sent young scholars to Kashmir for training and was responsible for inviting Atiśa to Tibet in 1040, thus ushering in the Chidar (Phyi dar) phase of Buddhism in Tibet. The younger son, Srong-nge, administered day-to-day governmental affairs; it was his sons who carried on the royal line.[21]

Central rule was largely nonexistent over the Tibetan region from 842 to 1247. According to traditional accounts, Buddhism had survived surreptitiously in the region of Kham. During the reign of Langdarma three monks had escaped from the troubled region of Lhasa to the region of Mt. Dantig in Amdo. Their disciple Muzu Saelbar (Mu-zu gSal-'bar), later known as the scholar Gongpa Rabsal (bla chen dgongs pa rab gsal) (832–915), was responsible for the renewal of Buddhism in northeastern Tibet, and is counted as the progenitor of the Nyingma (Rnying ma pa) school of Tibetan Buddhism. Meanwhile, according to tradition, one of Ösung's descendants, who had an estate near Samye, sent ten young men to be trained by Gongpa Rabsal. Among the ten was Lume Sherab Tshulthrim (Klu-mes Shes-rab Tshul-khrims) (950–1015). Once trained, these young men were ordained to go back into the central Tibetan regions of Ü and Tsang. The young scholars were able to link up with Atiśa shortly after 1042 and advance the spread and organization of Buddhism in Lho-kha. In that region, the faith eventually coalesced again, with the foundation of the Sakya Monastery in 1073.[22] Over the next two centuries, the Sakya monastery grew to a position of prominence in Tibetan life and culture. The Tsurphu Monastery, home of the Karmapa school of Buddhism, was founded in 1155.

Mongol conquest and Yuan administrative rule (1240–1354)

During this era, the region was dominated by the Sakya lama with the Mongols support, so it is also called the Sakya dynasty. The first documented contact between the Tibetans and the Mongols occurred when the missionary Tsang-pa Dung-khur (gTsang-pa Dung-khur-ba) and six disciples met Genghis Khan, probably on the Tangut border where he may have been taken captive, around 1221–2.[23] He left Mongolia as the Quanzhen sect of Daoism gained the upper hand, but remet Genghis Khan when Mongols conquered Tangut shortly before the Khan's death. Closer contacts ensued when the Mongols successively sought to move through the Sino-Tibetan borderlands to attack the Jin dynasty and then the Southern Song, with incursions on outlying areas. One traditional Tibetan account claims that there was a plot to invade Tibet by Genghis Khan in 1206,[24] which is considered anachronistic; there is no evidence of Mongol-Tibetan encounters prior to the military campaign in 1240.[25] The mistake may have arisen from Genghis' real campaign against the Tangut Xixia.[25][26]

The Mongols invaded Tibet in 1240, with a small campaign led by the Mongol general Doorda Darkhan,[27][28] that consisted of 30,000 troops[29][30] resulting in 500 casualties[31] The Mongols withdrew their soldiers from Tibet in 1241, as all the Mongol princes were recalled back to Mongolia in preparation for the appointment of a successor to Ögedei Khan.[32] They returned to the region in 1244, when Köten delivered an ultimatum, summoning the abbot of Sakya (Kun-dga' rGyal-mtshan) to be his personal chaplain, on pains of a larger invasion were he to refuse.[33] Sakya Paṇḍita took almost 3 years to obey the summons and arrive in Kokonor in 1246, and met Prince Köten in Lanzhou the following year. The Mongols had annexed Amdo and Kham to the east, and appointed Sakya Paṇḍita Viceroy of Central Tibet by the Mongol court in 1249.

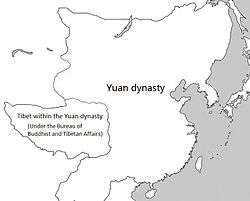

Tibet was incorporated into the Mongol Empire, retaining nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative[31][34] rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. This existed as a "diarchic structure" under the Mongol emperor, with power primarily in favor of the Mongols.[35] Within the branch of the Mongol Empire in China known as the Yuan dynasty, Tibet was managed by the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs or Xuanzheng Yuan, separate from other Yuan provinces such as those governed the former Song dynasty China. One of the department's purposes was to select a dpon-chen, usually appointed by the lama and confirmed by the Yuan emperor in Beijing.[35] "The Mongol dominance was most indirect: Sakya lamas remained the sources of authority and legitimacy, while the dpon-chens carried on the administration at Sakya. However there was no doubt as to who had the political clout. When a dispute developed between dpon-chen Kung-dga' bzari-po and one of 'Phags-pa's relatives at Sakya, the Chinese troops were dispatched to execute the dpon-chen."[35]

In 1253, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) succeeded Sakya Pandita at the Mongol court. Phagpa became a religious teacher to Kublai Khan. Kublai Khan appointed Chögyal Phagpa as his Imperial Preceptor (originally State Preceptor) in 1260, the year when he became Khagan. Phagpa developed the priest-patron concept that characterized Tibeto-Mongolian relations from that point forward.[36][37] With the support of Kublai Khan, Phagpa established himself and his sect as the preeminent political power in Tibet. Through their influence with the Mongol rulers, Tibetan lamas gained considerable influence in various Mongol clans, not only with Kublai, but, for example, also with the Il-Khanids.

In 1265, Chögyal Phagpa returned to Tibet and for the first time made an attempt to impose Sakya hegemony with the appointment of Shakya Bzang-po (a long time servant and ally of the Sakyas) as the dpon-chen ('great administrator') over Tibet in 1267. A census was conducted in 1268 and Tibet was divided into thirteen myriarchies. By the end of the century, Western Tibet lay under the effective control of imperial officials (almost certainly Tibetans) dependent on the 'Great Administrator', while the kingdoms of Guge and Pu-ran retained their internal autonomy.[38]

The Sakya hegemony over Tibet continued into the middle of the 14th century, although it was challenged by a revolt of the Drikung Kagyu sect with the assistance of Duwa Khan of the Chagatai Khanate in 1285. The revolt was suppressed in 1290 when the Sakyas and eastern Mongols burned Drikung Monastery and killed 10,000 people.[39]

Between 1346 and 1354, towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, the House of Pagmodru would topple the Sakya. The rule over Tibet by a succession of Sakya lamas came to a definite end in 1358, when central Tibet came under control of the Kagyu sect. "By the 1370s, the lines between the schools of Buddhism were clear."[40]

The following 80 years or so were a period of relative stability. They also saw the birth of the Gelugpa school (also known as Yellow Hats) by the disciples of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Dragpa, and the founding of the Ganden, Drepung, and Sera monasteries near Lhasa. After the 1430s, the country entered another period of internal power struggles.[41]

Rise of Phagmodrupa, Rinpungpa and Tsangpa

The Phagmodru (Phag mo gru) myriarchy centered at Neudong (Sne'u gdong) was granted as an appanage to Hülegü in 1251. The area had already been associated with the Lang (Rlang) family, and with the waning of Ilkhanate influence it was ruled by this family, within the Mongol-Sakya framework headed by the Mongol appointed Pönchen (Dpon chen) at Sakya. The areas under Lang administration were continually encroached upon during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Jangchub Gyaltsän (Byang chub rgyal mtshan, 1302–1364) saw these encroachments as illegal and sought the restoration of Phagmodru lands after his appointment as the Myriarch in 1322. After prolonged legal struggles, the struggle became violent when Phagmodru was attacked by its neighbours in 1346. Jangchub Gyaltsän was arrested and released in 1347. When he later refused to appear for trial, his domains were attacked by the Pönchen in 1348. Janchung Gyaltsän was able to defend Phagmodru, and continued to have military successes, until by 1351 he was the strongest political figure in the country. Military hostilities ended in 1354 with Jangchub Gyaltsän as the unquestioned victor, who established the Phagmodrupa Dynasty in that year. He continued to rule central Tibet until his death in 1364, although he left all Mongol institutions in place as hollow formalities. The rule of Jangchub Gyaltsän and his successors implied a new cultural self-awareness where models were sought in the age of the ancient Tibetan Kingdom. The relatively peaceful conditions favoured the literary and artistic development.[42] During this period the reformist scholar Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug sect which would have a decisive influence on Tibet's history. Power remained in the hands of the Phagmodru family until 1434.[43] After that, internal strife within the dynasty and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family Rinpungpa, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435. In 1565 they were overthrown by the Tsangpa Dynasty of Shigatse which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the Karma Kagyu sect. In spite of the weakening of central authority, the neighbouring Ming Dynasty of China made no efforts to impose direct rule, although it kept friendly relations with some of the lamas.[44] Tibet would be independent from the mid-14th century on, for nearly 400 years.[45]

Rise of Ganden Phodrang

Beginnings of the Dalai Lama lineage

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Practices and attainment |

|

History and overview |

|

Altan Khan, the king of the Tümed Mongols, first invited Sonam Gyatso, the head of the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism (and to be known later as the third Dalai Lama), to Mongolia in 1569. He invited him to Mongolia again in 1578, and this time he accepted the invitation. They met at the site of Altan Khan's new capital, Koko Khotan (Hohhot), and the Dalai Lama gave teachings to a huge crowd there.

Sonam Gyatso publicly announced that he was a reincarnation of the Tibetan Sakya monk Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) who converted Kublai Khan, while Altan Khan was a reincarnation of Kublai Khan (1215–1294), the famous ruler of the Mongols and Emperor of China, and that they had come together again to cooperate in propagating the Buddhist religion.[46] While this did not immediately lead to a massive conversion of Mongols to Buddhism (this would only happen in the 1630s), it did lead to the widespread use of Buddhist ideology for the legitimation of power among the Mongol nobility. Last but not least, Yonten Gyatso, the fourth Dalai Lama, was a grandson of Altan Khan.[47]

Rise of the Gelugpa schools

Yonten Gyatso (1589–1616), the fourth Dalai Lama and a non-Tibetan, was the grandson of Altan Khan. He died in 1616 in his mid-twenties. Some people say he was poisoned but there is no real evidence one way or the other.[48]

Lobsang Gyatso (Wylie transliteration: Blo-bzang Rgya-mtsho), the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, (1617–1682) was the first Dalai Lama to wield effective political power over central Tibet.

The fifth Dalai Lama is known for unifying the Tibetan heartland under the control of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, after defeating the rival Kagyu and Jonang sects and the secular ruler, the Tsangpa prince, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were successful in part because of aid from Güshi Khan, the Oirat leader of the Khoshut Khanate. The Jonang monasteries were either closed or forcibly converted, and that school remained in hiding until the latter part of the 20th century. With Güshi Khan as a largely uninvolved overlord, the 5th Dalai Lama and his intimates established a civil administration which is referred to by historians as the Lhasa state. This Tibetan regime or government is also referred to as the Ganden Phodrang.

In 1652, the fifth Dalai Lama visited the Shunzhi Emperor of the Qing dynasty. He was not required to kowtow like other visitors, but still had to kneel before the Emperor; and he received a seal.

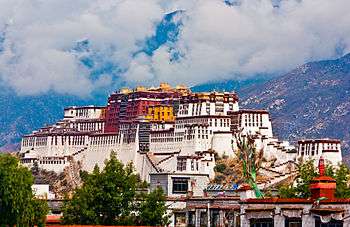

The fifth Dalai lama initiated the construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, and moved the centre of government there from Drepung.

The death of the fifth Dalai Lama in 1682 was kept hidden for fifteen years by his assistant, confidant, Desi Sangye Gyatso (De-srid Sangs-rgyas Rgya-'mtsho). The Dalai Lamas remained Tibet's titular heads of state until 1959.

During the rule of the Great Fifth, two Jesuit missionaries, the German Johannes Gruber and Belgian Albert Dorville, stayed in Lhasa for two months, October and November, 1661 on their way from Peking to Portuguese Goa, in India.[49] They described the Dalai Lama as a "powerful and compassionate leader" and "a devilish God-the-father who puts to death such as refuse to adore him." Another Jesuit, Ippolito Desideri, stayed five years in Lhasa (1716–1721) and was the first missionary to master the language. He even produced a few Christian books in Tibetan. Capuchin fathers took over the mission until all missionaries were expelled in 1745.

In the late 17th century, Tibet entered into a dispute with Bhutan, which was supported by Ladakh. This resulted in an invasion of Ladakh by Tibet. Kashmir helped to restore Ladakhi rule, on the condition that a mosque be built in Leh and that the Ladakhi king convert to Islam. The Treaty of Temisgam in 1684 settled the dispute between Tibet and Ladakh, but its independence was severely restricted.

Qing conquest and administrative rule (1720–1912)

During this era, the region was dominated by the Dalai Lamas with the support from the Qing dynasty established by the Manchus in China. The Qing rule over Tibet was established after a Qing expedition force defeated the Dzungars who occupied Tibet in 1720, and lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912. The Qing emperors appointed imperial residents known as the Ambans to Tibet, who commanded over 2,000 troops stationed in Lhasa and reported to the Lifan Yuan, a Qing government agency that oversaw the region during this period.[50]

The Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty sent an expedition army to Tibet in response to the occupation of Tibet by the forces of the Dzungar Khanate, together with Tibetan forces under Polhanas (also spelled Polhaney) of Tsang and Kangchennas (also spelled Gangchenney), the governor of Western Tibet,[51][52] They expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720. They brought Kelzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum to Lhasa and he was installed as the seventh Dalai Lama.[53][54] Qing protectorate over Tibet was established at this time, with a garrison at Lhasa, and Kham was annexed to Sichuan.[55] In 1721, the Qing established a government in Lhasa consisting of a council (the Kashag) of three Tibetan ministers, headed by Kangchennas. The Dalai Lama's role at this time was purely symbolic, but still highly influential because of the Mongols' religious beliefs.[56]

After the succession of the Yongzheng Emperor in 1722, a series of reductions of Qing forces in Tibet occurred. However, Lhasa nobility who had been allied with the Dzungars killed Kangchennas and took control of Lhasa in 1727, and Polhanas fled to his native Ngari. Qing troops arrived in Lhasa in September, and punished the anti-Qing faction by executing entire families, including women and children. The Dalai Lama was sent to Lithang Monastery[57] in Kham. The Panchen Lama was brought to Lhasa and was given temporal authority over Tsang and Ngari, creating a territorial division between the two high lamas that was to be a long lasting feature of Chinese policy toward Tibet. Two ambans were established in Lhasa, with increased numbers of Qing troops. Over the 1730s, Qing troops were again reduced, and Polhanas gained more power and authority. The Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in 1735, temporal power remained with Polhanas. The Qing found Polhanas to be a loyal agent and an effective ruler over a stable Tibet, so he remained dominant until his death in 1747.[58]

At multiple places such as Lhasa, Batang, Dartsendo, Lhari, Chamdo, and Litang, Green Standard Army troops were garrisoned throughout the Dzungar war.[59] Green Standard Army troops and Manchu Bannermen were both part of the Qing force who fought in Tibet in the war against the Dzungars.[60] It was said that the Sichuan commander Yue Zhongqi (a descendant of Yue Fei) entered Lhasa first when the 2,000 Green Standard soldiers and 1,000 Manchu soldiers of the "Sichuan route" seized Lhasa.[61] According to Mark C. Elliott, after 1728 the Qing used Green Standard Army troops to man the garrison in Lhasa rather than Bannermen.[62] According to Evelyn S. Rawski both Green Standard Army and Bannermen made up the Qing garrison in Tibet.[63] According to Sabine Dabringhaus, Green Standard Chinese soldiers numbering more than 1,300 were stationed by the Qing in Tibet to support the 3,000 strong Tibetan army.[64]

The Qing had made the region of Amdo and Kham into the province of Qinghai in 1724,[55] and incorporated eastern Kham into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.[65] The Qing government sent a resident commissioner (amban) to Lhasa. Polhanas' son Gyurme Namgyal took over upon his father's death in 1747. The ambans became convinced that he was going to lead a rebellion, so they killed him. News of the incident leaked out and a riot broke out in the city, the mob avenged the regent's death by killing the ambans. The Dalai Lama stepped in and restored order in Lhasa. The Qianlong Emperor (Yongzheng's successor) sent Qing forces to execute Gyurme Namgyal's family and seven members of the group that killed the ambans. The Emperor re-organized the Tibetan government (Kashag) again, nominally restoring temporal power to the Dalai Lama, but in fact consolidating power in the hands of the (new) ambans.[66]

The defeat of the 1791 Nepalese invasion increased the Qing's control over Tibet. From that moment, all important matters were to be submitted to the ambans.[67] It strengthened the powers of the ambans. The ambans were elevated above the Kashag and the regents in responsibility for Tibetan political affairs. The Dalai and Panchen Lamas were no longer allowed to petition the Qing Emperor directly but could only do so through the ambans. The ambans took control of Tibetan frontier defense and foreign affairs. The ambans were put in command of the Qing garrison and the Tibetan army (whose strength was set at 3000 men). Trade was also restricted and travel could be undertaken only with documents issued by the ambans. The ambans were to review all judicial decisions. However, according to Warren Smith, these directives were either never fully implemented, or quickly discarded, as the Qing were more interested in a symbolic gesture of authority than actual sovereignty.[68] In 1841, the Hindu Dogra dynasty attempted to establish their authority on Ü-Tsang but where defeated in the Sino-Sikh War (1841–1842).

In the mid 19th century, arriving with an Amban, a community of Chinese troops from Sichuan who married Tibetan women settled down in the Lubu neighborhood of Lhasa, where their descendants established a community and assimilated into Tibetan culture.[69] Hebalin was the location of where Chinese Muslim troops and their offspring lived, while Lubu was the place where Han Chinese troops and their offspring lived.[70]

European influences in Tibet

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The first Europeans to arrive in Tibet were Portuguese missionaries who first arrived in 1624 led by António de Andrade. They were welcomed by the Tibetans who allowed them to build a church. The 18th century brought more Jesuits and Capuchins from Europe. They gradually met opposition from Tibetan lamas who finally expelled them from Tibet in 1745. Other visitors included, in 1774 a Scottish nobleman, George Bogle, who came to Shigatse to investigate trade for the British East India Company, introducing the first potatoes into Tibet.[71] After 1792 Tibet, under Chinese influence, closed its borders to Europeans and during the 19th century only 3 Westerners, the Englishman Thomas Manning and 2 French missionaries Huc and Gabet, reached Lhasa, although a number were able to travel in the Tibetan periphery.

During the 19th century the British Empire was encroaching from northern India into the Himalayas and Afghanistan and the Russian Empire of the tsars was expanding south into Central Asia. Each power became suspicious of intent in Tibet. But Tibet attracted the attention of many explorers. In 1840, Sándor Kőrösi Csoma arrived in Darjeeling, hoping that he would be able to trace the origin of the Magyar ethnic group, but died before he was able to enter Tibet. In 1865 Great Britain secretly began mapping Tibet. Trained Indian surveyor-spies disguised as pilgrims or traders, called pundits, counted their strides on their travels across Tibet and took readings at night. Nain Singh, the most famous, measured the longitude, latitude and altitude of Lhasa and traced the Yarlung Tsangpo River.

British invasions of Tibet (1903-1904) and Qing control reasserted

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

At the beginning of the 20th century the British and Russian Empires were competing for supremacy in Central Asia. Unable to establish diplomatic contacts with the Tibetan government, and concerned about reports of their dealings with Russia, in 1903-04, a British expedition led by Colonel Francis Younghusband was sent to Lhasa to force a trading agreement and to prevent Tibetans from establishing a relationship with the Russians. In response, the Qing foreign ministry asserted that China was sovereign over Tibet, the first clear statement of such a claim.[72] Before the British troops arrived in Lhasa, the 13th Dalai Lama fled to Outer Mongolia, and then went to Beijing in 1908.

The British invasion was one of the triggers for the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion at Batang monastery, when anti-foreign Tibetan lamas massacred French missionaries, Manchu and Han Qing officials, and Christian converts before the Qing crushed the revolt.[73][74]

The Anglo-Tibetan Treaty of Lhasa of 1904 was followed by the Sino-British treaty of 1906. Beijing agreed to pay London 2.5 million rupees which Lhasa was forced to agree upon in the Anglo-Tibetan treaty of 1904.[75] In 1907, Britain and Russia agreed that in "conformity with the admitted principle of the suzerainty of China over Tibet"[76] both nations "engage not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government."[76]

The Qing government in Beijing then appointed Zhao Erfeng, the Governor of Xining, "Army Commander of Tibet" to reintegrate Tibet into China. He was sent in 1905 (though other sources say this occurred in 1908)[77] on a punitive expedition. His troops destroyed a number of monasteries in Kham and Amdo, and a process of sinification of the region was begun.[78][79] The Dalai Lama once again fled, this time to India, and was once again deposed by the Chinese.[80] The situation was soon to change, however, as, after the fall of the Qing dynasty in October 1911, Zhao's soldiers mutinied and beheaded him.[81][82] All remaining Qing forces left Tibet after the Xinhai Lhasa turmoil.

1912–1951: Republic of China rule with de facto independence

The Dalai Lama returned to Tibet from India in July 1912 (after the fall of the Qing dynasty), and expelled the Amban and all Chinese troops.[83] In 1913, the Dalai Lama issued a proclamation that stated that the relationship between the Chinese emperor and Tibet "had been that of patron and priest and had not been based on the subordination of one to the other."[84] "We are a small, religious, and independent nation", the proclamation continued.[84] For the next thirty-six years, Tibet enjoyed de facto independence while China endured its Warlord era, civil war, and World War II. Some Chinese sources argue that Tibet was still part of China throughout this period.[85] Some other authors argue that Tibet was also de jure independent after Tibet-Mongolia Treaty of 1913, before which Mongolia has been recognized by Russia.[86] Tibet continued in 1913–1949 to have very limited contacts with the rest of the world, although British representatives were stationed in Gyantse, Yatung and Gartok (western Tibet) after the Younghusband Mission. These so-called "Trade Agents" were in effect diplomatic representatives of the British Government of India and in 1936-37 the British also established a permanent mission in Lhasa. This was in response to a Chinese "condolence mission' sent to the Tibetan capital after the demise of the 13th Dalai Lama which remained in Lhasa as, in effect, a Republican Chinese diplomatic post. After 1947 the British mission was transferred to the newly independent Indian government control although the last British representative, Hugh Richardson remained in Lhasa until 1950 serving the Indian government. The British, like the Chinese, encouraged the Tibetans to keep foreigners out of Tibet and no foreigners visited Lhasa between the departure of the Younghusband mission in 1904 and the arrival of a telegraph officer in 1920.[87] Just over 90 European and Japanese visited Lhasa during the years 1920-1950, most of whom were British diplomatic personnel.[88] Very few governments did anything resembling a normal diplomatic recognition of Tibet. In 1914 the Tibetan government signed the Simla Accord with Britain, ceding the several small areas on the southern side of the Himalayan watershed to British India. The Chinese government denounced the agreement as illegal.[89][90]

In 1932, the National Revolutionary Army, composed of Muslim and Han soldiers, led by Ma Bufang and Liu Wenhui defeated the Tibetan army in the Sino-Tibetan War when the 13th Dalai Lama tried to seize territory in Qinghai and Xikang. It was also reported that the central government of China encouraged the attack, hoping to solve the "Tibet situation", because the Japanese had just seized Manchuria. They warned the Tibetans not to dare cross the Jinsha river again.[91] A truce was signed, ending the fighting.[92][93] The Dalai Lama had cabled the British in India for help when his armies were defeated, and started demoting his Generals who had surrendered.[94]

People's Republic of China rule (1950 to present)

In 1949, seeing that the Chinese Communists, with the decisive support from Joseph Stalin, were gaining control of China, the Kashag expelled all Chinese connected with the Chinese government, over the protests of both the Kuomintang and the Communists.[95] The Chinese Communist government led by Mao Zedong which came to power in October lost little time in asserting a new Chinese presence in Tibet. In October 1950, the People's Liberation Army entered the Tibetan area of Chamdo, defeating sporadic resistance from the Tibetan army. In 1951, Tibetan representatives participated in negotiations in Beijing with the Chinese government. This resulted in a Seventeen Point Agreement which formalized China's sovereignty over Tibet, but was repudiated by the present Tibetan Government-In-Exile shortly after.[96]

From the beginning, it was obvious that incorporating Tibet into Communist China would bring two opposite social systems face-to-face.[97] In Tibet, however, the Chinese Communists opted not to place social reform as an immediate priority. To the contrary, from 1951 to 1959, traditional Tibetan society with its lords and manorial estates continued to function unchanged.[97] Despite the presence of twenty thousand PLA troops in Central Tibet, the Dalai Lama's government was permitted to maintain important symbols from its de facto independence period.[97]

The Communists quickly abolished slavery and serfdom in their traditional forms. They also claim to have reduced taxes, unemployment, and beggary, and to have started work projects. They established secular schools, thereby breaking the educational monopoly of the monasteries, and they constructed running water and electrical systems in Lhasa.[98]

The Tibetan region of Eastern Kham, previously Xikang province, was incorporated in the province of Sichuan. Western Kham was put under the Chamdo Military Committee. In these areas, land reform was implemented. This involved communist agitators designating "landlords" — sometimes arbitrarily chosen — for public humiliation in thamzing (Wylie: ‘thab-‘dzing, Lhasa dialect IPA: [[tʰʌ́msiŋ]] ) or "Struggle Sessions", torture, maiming, and even death.[99][100][101]

By 1956 there was unrest in eastern Kham and Amdo, where land reform had been implemented in full. These rebellions eventually spread into western Kham and Ü-Tsang.

In 1956-57, armed Tibetan guerrillas ambushed convoys of the Chinese Peoples Liberation Army. The uprising received extensive assistance from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), including military training, support camps in Nepal, and several airlifts.[102] Meanwhile, in the United States, the American Society for a Free Asia, a CIA-financed front, energetically publicized the cause of Tibetan resistance, with the Dalai Lama's eldest brother, Thubten Norbu, playing an active role in that organization. The Dalai Lama's second-eldest brother, Gyalo Thondup, established an intelligence operation with the CIA as early as 1951. He later upgraded it into a CIA-trained guerrilla unit whose recruits parachuted back into Tibet.[103]

Many Tibetan commandos and agents whom the CIA dropped into the country were chiefs of aristocratic clans or the sons of chiefs. Ninety percent of them were never heard from again, according to a report from the CIA itself, meaning they were most likely captured and killed.[104] Ginsburg and Mathos reached the conclusion, that "As far as can be ascertained, the great bulk of the common people of Lhasa and of the adjoining countryside failed to join in the fighting against the Chinese both when it first began and as it progressed."[105] According to other data, many thousands of common Tibetans participated in the rebellion.[86] Declassified Soviet archives provides data that Chinese communists, who received a great assistance in military equipment from the USSR, broadly used Soviet aircraft for bombing monasteries and other punitive operations in Tibet.[86]

In 1959, China's military crackdown on rebels in Kham and Amdo led to the "Lhasa Uprising." Full-scale resistance spread throughout Tibet. Fearing capture of the Dalai Lama, unarmed Tibetans surrounded his residence, and the Dalai Lama fled to India.[106][107]

The period from 1959-1962 was marked by extensive starvation during the Great Chinese Famine brought about by drought and by the Chinese policies of the Great Leap Forward which affected all of China and not only Tibet. The Tenth Panchen Lama was a keen observer of Tibet during this period and penned the 70,000 Character Petition to detail the sufferings of the Tibetans and sent it to Zhou Enlai in May 1962.

In 1962, China and India fought a brief war over the disputed South Tibet and Aksai Chin regions. Although China won the war, Chinese troops withdrew north of the McMahon Line, effectively ceding South Tibet back to India.[90]

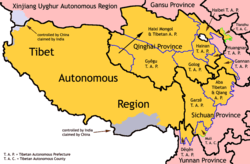

In 1965, the area that had been under the control of the Dalai Lama's government from the 1910s to 1959 (Ü-Tsang and western Kham) was renamed the Tibet Autonomous Region or TAR. Autonomy provided that the head of government would be an ethnic Tibetan; however, actual power in the TAR is held by the First Secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Regional Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, who has never been a Tibetan.[108] The role of ethnic Tibetans in the higher levels of the TAR Communist Party remains very limited.[109]

The destruction of most of Tibet's more than 6,000 monasteries occurred between 1959 and 1961 by the communist party of China.[110] During the mid-1960s, the monastic estates were broken up and secular education introduced. During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards.[111] inflicted a campaign of organized vandalism against cultural sites in the entire PRC, including Tibet's Buddhist heritage.[112] According to at least one Chinese source, only a handful of the religiously or culturally most important monasteries remained without major damage.[113]

In 1989, the Panchen Lama died of a massive heart attack at the age of 50.[114]

The PRC continues to portray its rule over Tibet as an unalloyed improvement, but as some foreign governments continue to make protests about aspects of PRC rule in Tibet as groups such as Human Rights Watch report alleged human rights violations. Most governments, however, recognize the PRC's sovereignty over Tibet today, and none have recognized the Government of Tibet in Exile in India.

Riots flared up again in 2008. Many ethnic Hans and Huis were attacked in the riot, their shops vandalized or burned. The Chinese government reacted swiftly, imposing curfews and strictly limiting access to Tibetan areas. The international response was likewise immediate and robust, with some leaders condemning the crackdown and large protests and some in support of China's actions.

Tibetans in exile

Following the Lhasa uprising and the Dalai Lama's flight from Tibet in 1959, the government of India accepted the Tibetan refugees. India designated land for the refugees in the mountainous region of Dharamsala, India, where the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile are now based.

The plight of the Tibetan refugees garnered international attention when the Dalai Lama, spiritual and religious leader of the Tibetan government in exile, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. The Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Prize on the basis of his unswerving commitment to peaceful protest against the Chinese occupation of Tibet. He is highly regarded as a result and has since been received by government leaders throughout the world. Among the most recent ceremonies and awards, he was given the Congressional Gold Medal by President Bush in 2007, and in 2006 he was one of only five people to ever receive an honorary Canadian citizenship (see Honorary Canadian citizenship). The PRC consistently protests each official contact with the exiled Tibetan leader.

The community of Tibetans in exile established in Dharamsala and Bylakuppe near Mysore in Karnataka, South India, has expanded since 1959. Tibetans have duplicated Tibetan monasteries in India and these now house tens of thousands of monks. They have also created Tibetan schools and hospitals, and founded the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives — all aimed at continuing Tibetan tradition and culture. Tibetan festivals such as Lama dances, celebration of Losar (the Tibetan New Year), and the Monlam Prayer Festival, continue in exile.

In 2006, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama declared that "Tibet wants autonomy, not independence."[115] However, the Chinese distrust him, believing that he has not really given up the quest for Tibetan independence.[116]

Talks between representatives of the Dalai Lama and the Chinese government began again in May, 2008 with little result.[117]

See also

- Tibet

- Tibetan Buddhist History

- History of Central Asia

- History of South Asia

- History of Ladakh

- List of rulers of Tibet

- Patron and priest relationship

- Pa Drengen Changchop Simpa

- Sinicization of Tibet

- 1959 Tibetan uprising

- 1987–1993 Tibetan unrest

- 2008 Tibetan unrest

- Tibetan Resistance Since 1950

Notes

- ↑ Laird 2006, p. 114-117.

- 1 2 Zhao M, Kong QP, Wang HW, Peng MS, Xie XD, Wang WZ, Jiayang, Duan JG, Cai MC, Zhao SN, Cidanpingcuo, Tu YQ, Wu SF, Yao YG, Bandelt HJ, Zhang YP. (2009). "Mitochondrial genome evidence reveals successful Late Paleolithic settlement on the Tibetan Plateau". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106: 21230–21235. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907844106 PMID 19955425

- 1 2 Helmut Hoffman in McKay 2003 vol. 1, pp. 45–68

- 1 2 Norbu 1989, pp. 127–128

- 1 2 Karmey 2001, p. 66ff

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Norbu 1995, p. 220

- ↑ Geoffrey Samuel, Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1993 p.441

- ↑ Rolf A.Stein, Tibetan Civilization, Faber, London 1972 pp.48f.Samuel, ibid p.441

- ↑ Haarh, The Yarluṅ Dynasty. Copenhagen: 1969.

- ↑ Beckwith 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ Thubten Jigme Norbu, with Colin Turnbull. Tibet:Its History, Religion and People, (1969) Penguin Books, 1972 p.30.

- ↑ Khar, Rabgong Dorjee (1991). "A Brief Discussion on Tibetan History Prior to Nyatri Tsenpo." Translated by Richard Guard and Sangye Tandar. The Tibet Journal. Vol. XVI No. 3. Autumn 1991, pp. 52-62. (This article originally appeared in the Tibetan quarterly Bod-ljongs zhib-'jug (No. 1, 1986).

- ↑ Beckwith, C. Uni. of Indiana Diss., 1977

- ↑ Beckwith 1987, p. 17.

- ↑ Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). 'The First Tibetan Empire' in: China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2

- ↑ Shakabpa. p.173.

- ↑ Schaik, Galambos. p.4.

- ↑ Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, Tibet, a Political History (New Haven: Yale, 1967), 53.

- ↑ Petech, L. The Kingdom of Ladakh, (Serie Orientale Roma 51) Rome: Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1977: 14–16

- ↑ Hoffman, Helmut, "Early and Medieval Tibet", in Sinor, David, ed., Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 388, 394. Shakabpa, 56.

- ↑ Grunfeld 1996, p37-38. Hoffman, 393. Shakabpa, 54-55.

- ↑ Paul D. Buell, 'Tibetans, Mongols and the Fusion of Eurasian Cultures,' in Anna Akasoy, Charles Burnett, Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (eds.) Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes, Ashgate Publishing, 2011, pp.188-208, p193-4.

- ↑ Wylie 1990, p. 105.

- 1 2 Wylie 1990, p. 106.

- ↑ "...erred in identifying Tibet as the country against Chinggis launched that early campaign. His military objective was the Tangut kingdom of Hsi-hsia."

- ↑ Wylie 1990, p. 110.

- ↑ "delegated the command of the Tibetan invasion to an otherwise unknown general, Doorda Darkhan".

- ↑ Shakabpa. p.61: 'thirty thousand troops, under the command of Leje and Dorta, reached Phanpo, north of Lhasa.'

- ↑ Sanders. p. 309, his grandson Godan Khan invaded Tibet with 30000 men and destroyed several Buddhist monasteries north of Lhasa

- 1 2 Wylie 1990, p. 104.

- ↑ Wylie 1990, p. 111.

- ↑ Buell, ibid. p.194: Shakabpa, 1967 pp.61-2.

- ↑ "To counterbalance the political power of the lama, Khubilai appointed civil administrators at the Sa-skya to supervise the mongol regency."

- 1 2 3 Dawa Norbu (2001). China's Tibet Policy. Psychology Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7007-0474-3.

- ↑ Laird 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ F. W. Mote. Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press, 1999. p.501.

- ↑ Alex McKay, History of Tibet, Routledge, 2003 p.40.

- ↑ Wylie 1990, p. 103-133.

- ↑ Laird 2006, p. 124.

- ↑ Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, München 2006, pp. 98–104

- ↑ Van Schaik, S. Tibet. A History. New Haven & London: Yale University Press 2011: 88–112.

- ↑ Petech, L. Central Tibet and The Mongols. (Serie Orientale Roma 65). Rome: Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente 1990: 85–143

- ↑ Tucci, G. Tibetan Painted Scrolls, Vol. 1-2. Rome 1949, Vol. 1: 692-3.

- ↑ Rossabi 1983, p. 194

- ↑ Laird 2006, p. 145.

- ↑ Michael Weiers, Geschichte der Mongolen, Stuttgart 2004, p. 175ff.

- ↑ Laird 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Wessels, C. Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603-1721. Books Faith, India. p. 188. ISBN 81-7303-105-3.

- ↑ Emblems of Empire: Selections from the Mactaggart Art Collection, by John E. Vollmer, Jacqueline Simcox, p154

- ↑ Mullin 2001, p. 290

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 125.

- ↑ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. Second Edition, Revised and Updated, pp. 48-9. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk)

- ↑ Schirokauer, 242

- 1 2 Stein 1972, pp. 85-88

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 126.

- ↑ Mullin 2001, p. 293

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 126-131.

- ↑ Wang 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Dai 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ Dai 2009, pp. 81-2.

- ↑ Elliott 2001, p. 412.

- ↑ Rawski 1998, p. 251.

- ↑ Dabringhaus 2014, p. 123.

- ↑ Wang Lixiong, "Reflections on Tibet", New Left Review 14, March–April 2002:'"Tibetan local affairs were left to the willful actions of the Dalai Lama and the shapes [Kashag members]", he said. "The Commissioners were not only unable to take charge, they were also kept uninformed. This reduced the post of the Residential Commissioner in Tibet to name only.'

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 191-2.

- ↑ Chambers' Encyclopedia, Pergamon Press, New York, 1967, p637

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 137.

- ↑ Yeh 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Yeh 2013, p. 283.

- ↑ Teltscher 2006, p. 57

- ↑ Michael C. Van Walt Van Praag. The Status of Tibet: History, Rights and Prospects in International Law, p. 37. (1987). London, Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-8133-0394-9.

- ↑ Bray, John (2011). "Sacred Words and Earthly Powers: Christian Missionary Engagement with Tibet". The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. fifth series. Tokyo: John Bray & The Asian Society of Japan (3): 93–118. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Tuttle, Gray (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0231134460.

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, Tibet, China and the United States: Reflections on the Tibet Question., 1995

- 1 2 Convention Between Great Britain and Russia (1907)

- ↑ FOSSIER Astrid, Paris, 2004 "L’Inde des britanniques à Nehru : un acteur clé du conflit sino-tibétain."

- ↑ Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, München 2006, p. 140f

- ↑ Goldstein 1989, p. 46f.

- ↑ Goldstein 1989, p. 49ff.

- ↑ Hilton 2000, p. 115

- ↑ Goldstein 1989, p. 58f.

- ↑ Shakya 1999, p. 5.

- 1 2 "Proclamation Issued by H.H. The Dalai Lama XIII"

- ↑ Tibet during the Republic of China (1912-1949)

- 1 2 3 Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation. Dharamsala, LTWA, 2011

- ↑ McKay 1997.

- ↑ Western and Japanese visitors to Lhasa 1900-1950. Jim Cooper. The Tibet Journal, 28/4/2003.

- ↑ Neville Maxwell (February 12, 2011). "The Pre-history of the Sino-Indian Border Dispute: A Note". Mainstream Weekly.

- 1 2 Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College.

- ↑ Xiaoyuan Liu (2004). Frontier passages: ethnopolitics and the rise of Chinese communism, 1921-1945. Stanford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8047-4960-4.

- ↑ Oriental Society of Australia (2000). The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, Volumes 31-34. Oriental Society of Australia. pp. 35, 37.

- ↑ Michael Gervers; Wayne Schlepp (1998). Historical themes and current change in Central and Inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, April 25–26, 1997, Volume 1997. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. pp. 73, 74, 76. ISBN 1-895296-34-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ K. Dhondup (1986). The water-bird and other years: a history of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and after. Rangwang Publishers. p. 60.

- ↑ Shakya 1999, p. 7-8.

- ↑ Goldstein 1989, p. 812-813.

- 1 2 3 Goldstein 2007, p541

- ↑ See Greene, A Curtain of Ignorance, 248 and passim; and Grunfeld, The Making of Modern Tibet, passim.

- ↑ Craig (1992), pp. 76-78, 120-123.

- ↑ Shakya 1999, p. 5, 245-249, 296, 322-323.

- ↑ "Unforgettable History – Old Tibet Serfdom System". Guangming Daily (in Chinese). Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ↑ See Kenneth Conboy and James Morrison, The CIA's Secret War in Tibet (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 2002); and William Leary, "Secret Mission to Tibet", Air & Space, December 1997/January 1998

- ↑ On the CIA's links to the Dalai Lama and his family and entourage, see Loren Coleman, Tom Slick and the Search for the Yeti (London: Faber and Faber, 1989).

- ↑ Leary, "Secret Mission to Tibet"

- ↑ George Ginsburg and Michael Mathos Communist China and Tibet (1964), quoted in Deane, The Cold War in Tibet. Deane notes that author Bina Roy reached a similar conclusion.

- ↑ Jackson, Peter, Witness: Reporting on the Dalai Lama's escape to India, Reuters, 27 Feb 2009

- ↑ "The CIA's secret war in Tibet", Seattle Times, January 26, 1997, Paul Salopek Ihttp://www.timbomb.net/buddha/archive/msg00087.html

- ↑ Dodin (2008), pp. 205.

- ↑ Dodin (2008), pp. 195-196.

- ↑ Craig (1992), p. 125.

- ↑ Shakya 1999, p. 320.

- ↑ Shakya 1999, p. 314-347.

- ↑ Wang 2001, pp. 212-214

- ↑ "Panchen Lama Poisoned arrow". BBC. 2001-10-14. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ↑ Bower, Amanda (April 16, 2006). "Dalai Lama: Tibet Wants Autonomy, Not Independence". Archived from the original on 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2008-04-25. (originally in TIME Magazine)

- ↑ "Commentary: Dalai Lama clique's deeds never square with its words". China View. March 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama's Envoys To Talk With Chinese. No Conditions Set; Transparency Calls Are Reiterated." by PETER WONACOTT, Wall Street Journal May 1, 2008

References

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05494-0. OCLC 15630380.

- Craig, Mary. (1992). Tears of Blood: A Cry for Tibet. INDUS an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Calcutta. Second impression, 1993. ISBN 0-00-627500-1

- Dodin, Thierry. (2008). "Right to Autonomy". In: Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions. Edited by Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-520-24928-8 (paper).

- Goldstein, Melvyn; Rimpoche, Gelek (1989). A history of modern Tibet, 1913-1951. Volume 1, The demise of the Lamaist state. Berkeley USA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8. OCLC 419892433.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (1997) University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21951-1

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 3: The Storm Clouds Descend, 1955-1957 (University of California Press; 2014) 547 pages;

- Grunfeld, A. Tom. The Making of Modern Tibet (1996) East Gate Book. ISBN 978-1-56324-713-2

- Hilton, Isabel (2000). The Search for the Panchen Lama. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-024670-3. ISBN 9780140246704.

- Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation (2011) Library of Tibetan Works & Archives. ISBN 978-93-80359-47-2

- Laird, Thomas; Dalai Lama XIV Bstan-ʼdzin-rgya-mtsho (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1. OCLC 63165009.

- McKay, Alex (1997). Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre, 1904-1947. Richmond, Surrey: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-0627-3. OCLC 37390564.

- McKay, Alex (ed.) (2003). The Early Period: to c. AD 850 The Yarlung Dynasty. New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

- McKay, Alex, ed. History of Tibet (Curzon in Association With Iias, 9) (2003) RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1508-8

- Mullin, Glenn H.The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnations (2001) Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 1-57416-092-3

- Norbu, Namkhai. The necklace of gZi: A Cultural History of Tibet (1989) Narthang.

- Norbu, Namkhai. Drung, deu, and Bön: narrations, symbolic languages, and the Bön traditions in ancient Tibet (1995) Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. ISBN 81-85102-93-7, ISBN 978-81-85102-93-1

- Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People's Republic of China (2004) Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7

- Rossabi, Morris. China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries (1983) Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04383-9

- Rossabi, Morris. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times (1989) Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06740-1

- van Schaik, Sam; Galambos, Imre. Manuscripts and Travellers: The Sino-Tibetan Documents of a Tenth-century Buddhist Pilgrim (2011) De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022564-8

- Shakya, Tsering (January 1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6533-9. OCLC 40840911. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Shirokauer, Conrad. A Brief History of Chinese Civilization Thompson Higher Education, (c) 2006. ISBN 0-534-64305-1

- Smith, Warren W. (24 October 1996). Tibetan nation: a history of Tibetan nationalism and Sino-Tibetan relations. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3155-3. OCLC 35192317.

- Sperling, Elliot (2004). The Tibet-China Conflict: History and Polemics (PDF). Washington: East-West Center. ISBN 1-932728-13-9. ISSN 1547-1330. - (online version)

- Stein, Rolf Alfred. Tibetan Civilization (1972) Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7; first published in French (1962). English translation by J. E. Stapelton Driver. Reprint: Stanford University Press (with minor revisions from 1977 Faber & Faber edition), 1995. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (hbk).

- Teltscher, Kate. The High Road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama and the First British Expedition to Tibet (2006) ISBN 0-374-21700-9; ISBN 978-0-7475-8484-1; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. ISBN 978-0-374-21700-6

- Wang Jiawei; Nyima Gyaincain (2001). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 7-80113-304-8.

- Willard J. Peterson, John King Fairbank, Denis C. Twitchett The Cambridge history of China: The Ch'ing empire to 1800 (2002) Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24334-3

- Wylie, Turnell (1990). "The First Mongol Conquest of Tibet Reinterpreted". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Yenching Institute. 37 (1): 103–133. doi:10.2307/2718667. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2718667. OCLC 6015211726.

Further reading

- Tuttle, Gray, and Kurtis R. Schaeffer, eds. The Tibetan History Reader (Columbia University Press, 2013), reprints major articles by scholars

- Bell, Charles: Tibet Past & Present. Reprint, New Delhi, 1990 (originally published in Oxford, 1924).

- Bell, Charles: Portrait of the Dalai Lama, Collins, London, 1946.

- Carrington, Michael. Officers Gentlemen and Thieves: The Looting of Monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet, Modern Asian Studies 37, 1 (2003), PP 81–109.

- Desideri (1932). An Account of Tibet: The Travels of Ippolito Desideri 1712-1727. Ippolito Desideri. Edited by Filippo De Filippi. Introduction by C. Wessels. Reproduced by Rupa & Co, New Delhi. 2005

- Rabgey, Tashi; Sharlho, Tseten Wangchuk (2004). Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the Post-Mao Era: Lessons and Prospects (PDF). Washington: East-West Center. ISBN 1-932728-22-8.

- Petech, Luciano (1997). China and Tibet in the Early XVIIIth Century: History of the Establishment of Chinese Protectorate in Tibet. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-03442-0.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (1993). Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1-56098-231-4.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon W.D [Wangchuk Deden (dbang phyug bde ldan)]: Tibet. A Political History, Potala Publications, New York, 1984.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (Dbang-phyug-bde-ldan, Zhwa-sgab-pa) (1907/08-1989): One Hundred Thousand Moons: an advanced political history of Tibet. Translated and annotated by Derek F. Maher. 2 Vol.,Brill, 2010 (Brill's Tibetan studies library; 23). Leiden, 2010.

- Smith, Warren W. (1996). History of Tibet: Nationalism and Self-determination. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3155-2.

- Smith, Warren W. (2004). China's Policy on Tibetan Autonomy - EWC Working Papers No. 2 (PDF). Washington: East-West Center.

- Smith, Warren W. (2008). China's Tibet?: Autonomy or Assimilation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-3989-1.

- McGranahan, C. "Truth, Fear, and Lies: Exile Politics and Arrested Histories of the Tibetan Resistance," Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 20, Issue 4 (2005) 570-600.

- Knaus, J.K. Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival (New York: Public Affairs, 1999).

- Bageant, J. "War at the Top of the World," Military History, Vol. 20, Issue 6 (2004) 34-80.

External links

- "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources" S. W. Bushell, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, New Series, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Oct., 1880), pp. 435–541, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- Brief History of Tibet at Friends of Tibet New Zealand

- Fifty Years after the Asian Relations Conference, Sharan, 1997, Tibetan Parliamentary and Policy Research Centre

- Tibetan Buddhist Texts Chronology

- The Shadow Circus: The CIA in Tibet - Documentary website

- Tibetan History according to China, at Xinhua

- Remembering Tibet as an independent nation

- Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation. LTWA, 2011

- Old TibetanDocuments Online