Wilhelmus

| English: William | |

|---|---|

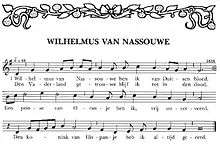

Early version of the Wilhelmus as preserved in a manuscript from 1617[1] | |

|

National anthem of | |

| Lyrics | disputed, 1568 ~ 1572 |

| Music | adapted by Adrianus Valerius, composer of original unknown, 1568 |

| Adopted |

1932 (officially) 1954 (Netherlands Antilles) |

| Relinquished | 1964 (Netherlands Antilles) |

|

| |

| Music sample | |

| Wilhelmus (instrumental) | |

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe, usually known just as the Wilhelmus (Dutch: Het Wilhelmus; pronounced [ɦɛt ʋɪlˈɦɛlmɵs]; English translation: the William), is the national anthem of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the oldest known national anthem in the world.[2] The national anthem of Japan, Kimigayo, has the oldest lyrics, dating from the 9th century. However, a melody was only added in the late 19th century, making it a poem rather than an anthem for most of its lifespan. Although the Wilhelmus was not recognised as the official national anthem until 1932, it has always been popular with parts of the Dutch population and resurfaced on several occasions in the course of Dutch history before gaining its present status.[3] It was also the anthem of the Netherlands Antilles from 1954–1964.

Like many anthems, the Wilhelmus originated in the nation's struggle to achieve independence. It tells of the Father of the Nation William of Orange who was stadholder in the Netherlands under the king of Spain. In the first person, as if quoting himself, William speaks to the Dutch people ("mijn ondersaten", my subjects) and tells about both the outer conflict – the Dutch Revolt – as well as his own, inner struggle: on one hand, he tries to be faithful to the king of Spain,[4] on the other hand he is above all faithful to his conscience: to serve God and the Dutch people. This is made apparent in the 8th stanza where the comparison is made between the biblical David who serves under the tyrannic king Saul, and William who serves under the King of Spain. As the merciful David defeats the unjust Saul and is rewarded by God with the kingdom of Israel, so too, with the help of God, will William be rewarded a kingdom; being either or both the Netherlands, and the kingdom of God.

Both the Wilhelmus and the Dutch Revolt should be seen in the light of the Reformation in Europe in the 16th century, and the resulting prosecution of Protestants (Calvinists) by the Spanish Inquisition in the Low Countries, then part of the Spanish Empire. Protestant propagandists across Europe found that music proved useful in generating class transcending social cohesion, and in lampooning Roman clerks and repressive monarchs. The Wilhelmus stands as the preeminent example of this militant music. It combines a psalmic character with political relevancy.[5]

Inception

Authorship melody

The melody of the Wilhelmus was borrowed from a well known Roman Catholic French song titled "Autre chanson de la ville de Chartres assiégée par le prince de Condé" or in short: "Chartres". This song ridiculed the failed Siege of Chartres in 1568 by the Huguenot (Protestant) Prince de Condé during the French Wars of Religion. However, the triumphant contents of the Wilhelmus is the opposite of the content of the original song, making it subversive at several levels. Thus, the Dutch Protestants had taken over an anti-Protestant song, and adapted it into propaganda for their own agenda. In that way, the Wilhelmus was typical for its time, since It was common practice in the 16th century for warring groups to steal each other's songs in order to rewrite them.[6]

Even though the melody stems from 1568, the first known written down version of it comes from 1574, in the time the anthem was sung in a much quicker pace. Dutch composer Adriaen Valerius recorded the current melody of the Wilhelmus in his "Nederlantsche Gedenck-clanck" in 1626, slowing down the melody's pace, probably to allow it to be sung in churches. The current official version is the 1932 arrangement by Walther Boer.

Authorship lyrics

The origins of the lyrics are uncertain. The Wilhelmus was first written some time between the start of the Eighty Years' War in April 1568 and the Capture of Brielle on 1 April 1572,[7] making it at least 443–444 years old. Soon after the anthem was finished it was said that either Philips of Marnix, a writer, statesman and former mayor of Antwerp, or Dirck Coornhert, a politician and theologian, wrote the lyrics. However, this is disputed as both Marnix and Coornhert never mentioned that they wrote the lyrics. This is strange since the song was immensely popular in their time. The Wilhelmus also has some odd rhymes in it. In some cases the vowels of certain words were altered to allow them to rhyme with other words. Some see this as evidence that neither Marnix or Coornhert wrote the anthem as they were both experienced poets when the Wilhelmus was written and they would not have taken these small liberties. Hence some believe that the lyrics of the Dutch national anthem were the creation of someone who just wrote one poem for the occasion and then disappeared from history. A French translation of the Wilhelmus appeared around 1582.[8]

Recent stylometric research mentioned Petrus Dathenus as a possible author of the text of the Dutch national anthem.[9] Dutch and Flemish researchers (Meertens Institute, Utrecht University and University of Antwerp) discovered by chance a striking number of similarities between his style and the style of the national anthem.[10][11]

Structure and interpretation

The complete text comprises fifteen stanzas. The anthem is an acrostic: the first letters of the fifteen stanzas formed the name 'Willem van Nassov' (Nassov was a contemporary orthographic variant of Nassau). In the current Dutch spelling the first words of the 12th and 13th stanzas begin with Z instead of S.

Like many of the songs of the period, it has a complex structure, composed around a thematic chiasmus: the text is symmetrical, in that verses one and 15 resemble one another in meaning, as do verses two and 14, three and 13, etc., until they converge in the 8th verse, the heart of the song: "Oh David, thou soughtest shelter from King Saul's tyranny. Even so I fled this welter", where the comparison is made between the biblical David and William of Orange as merciful and just leader, between the tyran King Saul and the Spanish crown, and between the promised land of Israel granted by God to David, and the Netherlands.[12]

The last two lines of the first stanza however, indicate that the leader of the Dutch civil war against the Spanish Empire of which they were part, had no specific quarrel with king Philip II of Spain, but rather with his emissaries in the Low Countries, like Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba. This may have been because at the time (late 16th century) it was uncommon to publicly doubt the Divine Right of Kings, who was accountable to God alone.[13] In 1581 the Netherlands nevertheless rejected the legitimacy of the king of Spain's rule over it in the Act of Abjuration.

"Duytschen" (in English generally translated as "Dutch" or "native") in the first stanza as a reference to William's roots, whose modern Dutch equivalent, "Duits", exclusively means "German", may refer to William's ancestral house (Nassau, Germany) or to the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, including the Netherlands.[14][15] But most probably it is simply a reference to the broader meaning of the word, which points out William as a ''native'' of the fatherland, as appose to the king of Spain, who was seldom or not in the Netherlands. The prince thus states that his roots are Germanic rather than Romance – in spite of his being Prince of Orange in France as well.[16] See also Theodiscus and Low Countries (terminology).

Performance

History

Though only proclaimed the national anthem in 1932, the Wilhelmus already had a centuries-old prior history. It had been sung on many official occasions and at many important events since the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt in 1568, such as the siege of Haarlem in 1573 and the ceremonial entry of the Prince of Orange into Brussels on 18 September 1578.

It has been claimed that during the gruesome torture of Balthasar Gérard (the assassin of William of Orange) in 1584, the song was sung by the guards who sought to overpower Gérard's screams when boiling pigs' fat was poured over him. Gérard allegedly responded "Sing! Dutch sinners! Sing! But know that soon I shall be sung of!".[17]

Another legend claims that following the Navigation Acts (a 1651 ordinance by Oliver Cromwell requiring all foreign fleets in the North Sea or the Channel to dip their flag in salute) the Wilhelmus was sung (or rather, shouted) by the sailors on the Dutch flagship Brederode in response to the first warning shot fired by an English fleet under Robert Blake, when their captain Maarten Tromp refused to lower his flag. At the end of the song, which coincided with the third (i.e. last) English warning shot, Tromp fired a full broadside thereby beginning the Battle of Goodwin Sands and the First Anglo-Dutch War.[18]

During the Dutch Golden Age, it was conceived essentially as the anthem of the House of Orange-Nassau and its supporters – which meant, in the politics of the time, the anthem of a specific political faction which was involved in a prolonged struggle with opposing factions (which sometimes became violent, verging on civil war). Therefore, the fortunes of the song paralleled those of the Orangist faction. Trumpets played the Wilhelmus when Prince Maurits visited Breda, and again when he was received in state in Amsterdam in May 1618. When William V arrived in Schoonhoven in 1787, after the authority of the stadholders had been restored, the church bells are said to have played the Wilhelmus continuously. After the Batavian Revolution, inspired by the French Revolution, it had come to be called the "Princes' March" as it was banned during the rule of the Patriots, who did not support the House of Orange-Nassau.

However, at the foundation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1813, the Wilhelmus had fallen out of favour. Having become monarchs with a claim to represent the entire nation and stand above factions, the House of Orange decided to break with the song which served them as heads of a faction, and the Wilhelmus was hence replaced by Hendrik Tollens' song Wien Neêrlands bloed door d'aderen vloeit, which was the official Dutch anthem from 1815 till 1932. However, the Wilhelmus remained popular and lost its identification as a factional song, and on 10 May 1932, it was decreed that on all official occasions requiring the performance of the national anthem, the Wilhelmus was to be played – thereby replacing Tollens' song.

During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Nazi Reichskommissar, banned all the emblems of the Dutch royal family, including the Wilhelmus. This was then taken up by all factions of the Dutch resistance, even those socialists who had previously taken an anti-monarchist stance. The pro-German Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB), who had sung the Wilhelmus at their meetings before the occupation, replaced it with Alle Man van Neerlands Stam ("All Men of Dutch Origin").[19] The anthem was drawn to the attention of the English-speaking world by the 1942 British war film, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing. The film concerns a Royal Air Force bomber crew who are shot down over the occupied Netherlands and are helped to escape by the local inhabitants. The melody is heard during the film as part of the campaign of passive resistance by the population, and it finishes with the coat of arms of the Netherlands on screen while the Wilhelmus is played.[20]

Current

The Wilhelmus is played only once at a ceremony or whatever other event and, if possible, it is to be the last piece of music to be played. When receiving a foreign head of state or emissary, the Dutch anthem may not be played unless a member of the Dutch Royal House is present. This is virtually unique in the world as most countries play the anthem of the foreign relation followed by their own anthem.

During international sport events, such as the World Cup, UEFA European Football Championship and the Olympic Games the Wilhelmus is also played. In nearly every case the 1st and 6th stanza (or repeating the last lines), or the 1st stanza alone, are sung/played rather than the entire song, which would result in about 15 minutes of music.[21]

The "Wilhelmus" is also widely used in Flemish nationalist gatherings as a symbol of cultural unity with the Netherlands. Yearly rallies like the "IJzerbedevaart" and the "Vlaams Nationaal Zangfeest" close with singing the 6th stanza, after which the Flemish national anthem "De Vlaamse Leeuw" is sung.

Variations

An important set of variations on the melody of Wilhelmus van Nassouwe is that by the blind carillon-player Jacob Van Eyck in his mid-17th century collection of variations Der Fluyten Lust-hof.[22]

The royal anthem of Luxembourg, called de Wilhelmus, has a shared origin with the Dutch anthem het Wilhelmus. It is in official use since 1919, and was first used in Luxembourg (at the time in personal union with the Kingdom of the United Netherlands) on the occasion of the visit of the Dutch King and Grand Duke of Luxembourg William III in 1883. Later, the anthem was played for Grand Duke Adolph of Luxembourg along with the national anthem. The melody is very similar, but not identical to that of the Wilhelmus, since the melody of the latter has been adapted considerably in history.

The melody is used, with rewritten English lyrics, as the alma mater of Northwestern College in Orange City, Iowa, USA. Northwestern College is associated with the historically Dutch Christian denomination the Reformed Church in America. Orange City, the college's location, is named for the House of Orange. Small local governmental districts, townships, are named Nassau, Holland and East Orange.

Lyrics

|

The Wilhelmus

A choir accompanied by an organ sings the first and sixth stanza. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The Wilhelmus was first printed in a geuzenliedboek, literally "Beggars' songbook" in 1581. It used the following text as an introduction to the Wilhelmus:

Een nieuw Christelick Liedt gemaect ter eeren des Doorluchtichsten Heeren, Heere Wilhelm Prince van Oraengien, Grave van Nassou, Patris Patriae, mijnen Genaedigen Forsten ende Heeren. Waer van deerste Capitael letteren van elck veers syner Genaedigen Forstens name metbrengen. Na de wijse van Chartres.

A new Christian song made in the honour of the most noble lord, lord William Prince of Orange, count of Nassau, Pater Patriae (Father of the Nation), my merciful prince and lord. [A song] of which the first capital letter of each stanza form the name of his merciful prince. To the melody of Chartres.

| Original Dutch lyrics (1568) | Contemporary Dutch lyrics | Melodic English lyrics[23] | Non-melodic English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| First stanza | |||

|

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe |

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe |

William of Nassau, scion |

William of Nassau |

| Second stanza | |||

|

In Godes vrees te leven |

In Godes vrees te leven |

I've ever tried to live in |

To live in fear of God |

| Third stanza | |||

|

Lydt u myn Ondersaten |

Lijdt u, mijn onderzaten |

Let no despair betray you, |

Hold on my subjects, |

| Fourth stanza | |||

|

Lyf en goet al te samen |

Lijf en goed al te samen |

Life and my all for others |

My life and fortune altogether |

| Fifth stanza | |||

|

Edel en Hooch gheboren |

Edel en hooggeboren, |

I, nobly born, descended |

Noble and high-born, |

| Sixth stanza | |||

|

Mijn Schilt ende betrouwen |

Mijn schild ende betrouwen |

A shield and my reliance, |

My shield and reliance |

| Seventh stanza | |||

|

Van al die my beswaren, |

Van al die mij bezwaren |

My God, I pray thee, save me |

From all those that burden me |

| Eighth stanza | |||

|

Als David moeste vluchten |

Als David moeste vluchten |

O David, thou soughtest shelter |

Like David, who was forced to flee |

| Ninth stanza | |||

|

Na tsuer sal ick ontfanghen |

Na 't zuur zal ik ontvangen |

Fear not 't will rain sans ceasing |

After this sourness I will receive |

| Tenth stanza | |||

|

Niet doet my meer erbarmen |

Niets doet mij meer erbarmen |

Nothing so moves my pity |

Nothing makes me pity so much |

| Eleventh stanza | |||

|

Als een Prins op gheseten |

Als een prins opgezeten |

Astride on steed of mettle |

Seated [on horseback] like a prince, |

| Twelfth stanza | |||

|

Soo het den wille des Heeren |

Zo het de wil des Heren |

Surely, if God had willed it, |

If it had been the Lord's will, |

| Thirteenth stanza | |||

|

Seer Prinslick was ghedreven |

Zeer christlijk was gedreven |

Steadfast my heart remaineth |

By a Christian mood was driven |

| Fourteenth stanza | |||

|

Oorlof mijn arme Schapen |

Oorlof, mijn arme schapen |

Alas! my flock. To sever |

Farewell, my poor sheep, |

| Fifteenth stanza | |||

|

Voor Godt wil ick belijden |

Voor God wil ik belijden |

Unto the Lord His power |

I want to confess to God, |

| Acrostic | |||

|

WILLEM VAN NASSOV |

WILLEM VAN NAZZOV |

WILLIAM OF NASSAU |

(n/a) |

Notes and references

- ↑ M. de Bruin, "Het Wilhelmus tijdens de Republiek", in: L.P. Grijp (ed.), Nationale hymnen. Het Wilhelmus en zijn buren. Volkskundig bulletin 24 (1998), p. 16-42, 199–200; esp. p. 28 n. 65.

- ↑ national-anthems.org – facts National Anthems facts

- ↑ "Netherlands – Het Wilhelmus". NationalAnthems.me. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ CF.hum.uva.nl

- ↑ DeLapp, Nevada Levi (2014-08-28). The Reformed David(s) and the Question of Resistance to Tyranny: Reading the Bible in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 9780567655493.

- ↑ "Geuzenliedboek". cf.hum.uva.nl. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "Louis Peter Grijp-lezing 10 mei 2016". Vimeo. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ J. te Winkel, De ontwikkelingsgang der Nederlandsche letterkunde. Deel 2: Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde van Middeleeuwen en Rederijkerstijd (Haarlem 1922), p. 491 n. 1.DBNL.org

- ↑ "'Schrijver Wilhelmus is te ontdekken met computeralgoritme'" (in Dutch). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "Toevallig op Petrus Datheen stuiten" (in Dutch). 2016-05-11. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "Louis Peter Grijp-lezing online" (in Dutch). 2016-05-22. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ DeLapp, Nevada Levi (2014-08-28). The Reformed David(s) and the Question of Resistance to Tyranny: Reading the Bible in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 88–90. ISBN 9780567655493.

- ↑ DeLapp, Nevada Levi (2014-08-28). The Reformed David(s) and the Question of Resistance to Tyranny: Reading the Bible in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 155. ISBN 9780567655493.

- ↑ Maria A. Schenkeveld, Dutch literature in the age of Rembrandt: themes and ideas (1991), 6

- ↑ Leerssen, J. (1999). Nationaal denken in Europa: een cultuurhistorische schets. p. 29.

- ↑ DeGrauwe, Luc (2002). Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period, in: in: Standardisation: studies from the Germanic languages. pp. 99–116.

- ↑ van Doorn, T. H. "Het Wilhelmus, analyse van de inhoud, de structuur en de boodschap.". www.cubra.nl. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ van Doorn, T. H. "Het Wilhelmus, analyse van de inhoud, de structuur en de boodschap.". www.cubra.nl. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ Dewulf, Jeroen (2010), Spirit of Resistance: Dutch Clandestine Literature During the Nazi Occupation, Camden House, New York ISBN 978-1-57113-493-6 (p. 115)

- ↑ Furhammar, Leif and Isaksson, Folke (1971), Politics and film, Praeger Publishers, New York (p. 81)

- ↑ Each of the 15 stanzas lasts 56 seconds, and the last stanza has a Ritenuto.

- ↑ Michel, Winfried and Hermien Teske (eds.) (1984). Jacob van Eyck (ca. 1590–1657): Der Fluyten Lust-hof. Winterthur: Amadeus Verlag – Bernhard Päuler.

- ↑ "The Dutch National Anthem". MinBuZa.nl. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

External links

| English Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wilhelmus. |

- Streaming audio, lyrics and information for the Wilhelmus

- Sheet music of the Wilhelmus

- "The Wilhelmus", vocal version of the first and sixth verse at the Himnuszok website

- O la folle entreprise du prince de Condé, performance of Autre chanson de la ville de Chartres assiégée par le prince de Condé, the song that has the original version of the melody used for the Wilhelmus

- Het Wilhelmus (reconstruction), in the pace of the 16th century version