Terminology of the Low Countries

The Low Countries (Dutch: de Lage Landen, French: les Pays-Bas) is the coastal Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta region in Western Europe and consists mainly of the Netherlands and Belgium.[1][2] Both countries derived their names from it, due to nether meaning "low" and Belgica being the Latin name for the Low Countries, a nomenclature that went obsolete after Belgium's secession in 1830.

The Low Countries—and the Netherlands and Belgium—had in their history exceptionally many and widely varying names, resulting in equally varying names in different languages. There is diversity even within languages: the use of one word for the country and another for the adjective form is common. This holds for English, where Dutch is the adjective form for the country "the Netherlands". Moreover, many languages have the same word for both the country of the Netherlands and the region of the Low Countries, e.g., French (les Pays-Bas) and Spanish (los Países Bajos). The complicated nomenclature is a source of confusion for outsiders, and is due to the long history of the language, the culture and the frequent change of economic and military power within the Low Countries over the past 2000 years.

The historic Low Countries made up much of Frisia, home to the Frisii, and the Roman provinces of Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior, home to the Belgae and Germanic peoples like the Batavi. Throughout the centuries, the names of these ancestors have been in use as a reference to the Low Countries, in an attempt to define a collective identity. But it was in the fourth and fifth centuries that a Frankish confederation of Germanic tribes significantly made a lasting change by entering the Roman provinces and starting to build the Carolingian Empire, of which the Low Countries formed a core part.

By the eighth century, most of the Franks had exchanged their Germanic Franconian languages for the Latin-derived Romances of Gaul. However, the Franks that stayed in the Low Countries had kept their original language, i.e., Old Dutch, also known as "Old Low Franconian" among linguists. At the time the language was spoken, it was known as *þiudisk, meaning "of the people"—as opposed to the Latin language "of the clergy"—which is the source of the English word Dutch. Now an international exception, it used to have in the Dutch language itself a cognate with the same meaning, i.e., Diets(c) or Duuts(c).

The designation "low" to refer to the region has also been in use many times. First by the Romans, who called it Germania "Inferior". After the Frankish empire was divided several times, most of it became the Duchy of Lower Lorraine in the tenth century, where the Low Countries politically have their origin.[3][4] Lower Lorraine disintegrated into a number of duchies, counties and bishoprics. Some of these became so powerful, that their names were used as a pars pro toto for the Low Countries, i.e., Flanders, Holland and to a lesser extent Brabant. Burgundian, and later Habsburg rulers[5][6] added one by one the Low Countries' polities in a single territory, and it was at their francophone courts that the term les pays de par deçà arose, that would develop in Les Pays-Bas or in English "Low Countries" or "Netherlands".

In general, the names for the language, for the region, and for the countries within the region, and the adjective forms can all be arranged in five main groups according to their origin: it is a reference to a non-Latin, Germanic language—þiudisk—(Dietsc, "Dutch", Nederduits), whose speakers are ancestral to local Germanic tribes (Belgae, Batavi, Frisii); these tribes dissolved into confederations (Franconian, Frisian) which consolidated into local, economic powerful polities (Flanders, Brabant, Holland) in the low-lying, down river land at the North Sea (Germania Inferior, Lower Lorraine, Low Countries, Netherlands).

From theodiscus

Dutch and Diets

English is the only language to use the adjective "Dutch" for the language of the Netherlands and Flanders or something else from the Netherlands. The word is derived from Proto-Germanic *þiudiskaz. The stem of this word, *þeudō, meant "people" in Proto-Germanic, and *-iskaz was an adjective-forming suffix, of which -ish is the Modern English form.[7] The word came into Middle English as thede, but was extinct in Early Modern English (although surviving in the English place name Thetford, "public ford"). It survives as the Icelandic word þjóð for "people, nation", the Norwegian word tjod for "people", "nation", and the word for "German" in many European languages.

Theodiscus is the Latinised form derived from West Germanic *þiudisk[8] and used as an adjective referring to the Germanic vernaculars of the Early Middle Ages and thus is one of the first names ever used for the non-Romance languages of Western Europe. It literarily means "the language of the common people", that is, the native Germanic language. The term was used as opposed to Latin, the non-native language of writing and the Catholic Church.[9] In its first recorded sense theodiscus was used within a clearly clerical context and referred to Old English.[10] Around the year 786 the Bishop of Ostia writes to Pope Adrian I about a synod taking place in Corbridge, England, where the decisions are being written down "tam Latine quam theodisce" meaning "in Latin as well as Germanic".[11][12][13] Starting in the 9th century, the term diutisk is used in Francia to denote the vernaculars spoken by the general populace,[11] and it effectively became the antonym of walhisk, which referred to the speakers of Romance and Celtic languages and which forms the root for modern terms such as Welsh, Walloon, Wallis and welsch.

In Great Britain the term Englisc was already common from the Early Middle Ages onwards, with the Angles, Saxons and Jutes being collectively referred to as 'English' as early as 731.[14] The word would show inconsistencies during most of the Middle Ages, with Robert of Gloucester still making a distinction between "Þe englisse in þe norþ half, þe saxons bi souþe" ("the English in the North, the Saxons in the south") around the start of the 14th century, but the use of English as a term to describe a unit surpassing the tribe, county or distant cultural affiliation predates the use of comparable terms on the European mainland.[11][12][13]

The Old English variant þeodisc was subsequently during the Middle Ages influenced from Middle Dutch, were it had two principal forms of the word, a southern variant duutsch/duitsch and a western variant dietsch, and was then mainly used to refer to the inhabitants of the Low Countries, with whom there was extensive trade. Though initially also encompassing a broader definition signifying "speakers of Germanic languages on the continent / Non-Romance speakers" the use of the word "Dutch" in this sense was rare and would become obsolete following the growing and intensive rivalry between England and the Dutch Republic during the 17th century.[15][16]

In the Low Countries, Dietsch was used alongside Nederlands, which referred exclusively to Dutch and would become the modern Dutch autonym, while Duits (though not Diets) would increasingly come to refer to German dialects as opposed to Dutch.[15][17] In the United States the German autonym Deutsch would sometimes be corrupted to "Dutch" due to the similar pronunciation of both words. A well known example are the Pennsylvania Dutch who were originally German immigrants, speak a German dialect and refer to themselves as Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

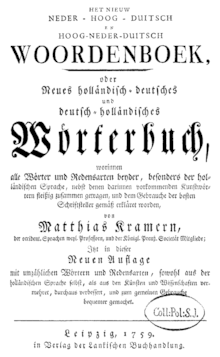

Nederduits

From the second half of the 16th until the middle of the 18th century, Nederduits appears as the nomenclature for the Dutch language among both scholars and writers of literature.[25][26] Not only because it was perceived as modern, but also because nederig also means "humble" in Dutch, thus invoking the sense of a humble language, forming a wordplay, which appealed to the highly religious Dutch people of the time and the low lying features of their country.[27] However, the early 19th century, saw the emergence of modern Germanic linguistics, and German linguists used the term Niederdeutsch for the German varieties spoken in the North of Germany which did not experience the High German consonant shift. Dutch linguists subsequently calqued the terminology, and used Nederduits as its translation for these German dialects.[28] As a result, Nederduits started to have two meanings. To avoid this confusion Nederlands as a reference to the Dutch language prevailed over Nederduits. The Nederduits Hervormde Kerk in Nederland changed in the 19th century its name in Nederlands Hervormde Kerk, however in South Africa, offshoots of this church kept their old name in the Dutch-related Afrikaans. Thus the Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk van Afrika is translated in English as "Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NHK)" and the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk as "Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK)".

From low-lying geographical features

Low in relation to high

Place names with "low(er)" or neder, lage, nieder, nether, nedre, bas and inferior are used everywhere in Europe. They are often used as a place deixis, opposed to either an upstream or higher ground that consecutively is indicated as "upper" or boven, oben, superior and haut. Both downstream at the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, and low at the plain near the North Sea apply to the Low Countries or the Netherlands. However, the related geographical location of the "upper" ground changed over time tremendously.

Germania inferior

The Romans made a distinction between the Roman provinces of downstream Germania Inferior (nowadays part of Belgium and the Netherlands) and upstream Germania Superior (nowadays part of southern Germany).

Lower Lorraine

The designation "low" to refer to the region returns again in the 10th century Duchy of Lower Lorraine, that covered much of the Low Countries.[3][4] But this time the corresponding "upper" region is the Upper Lorraine, which is now Northern France.

Neder Zassen

In the 13th century, the Dutch medieval poet Melis Stoke wrote in his Rijmkroniek that the term Neder Zassen ("Lower-Saxony") used to be all the land between Scheldt and Elbe, thus including much of the coastal area of the Low Countries, more specifically the area where the Frisians live. In that case, the upper ground would have been located in Saxony, in the northwest corner of Germany.[29]

Les pays de par deçà

The Dukes of Burgundy, who ruled the Low Countries (the "Burgundian Netherlands") in the 15th century, used the term les pays de par deçà ("the lands over here") for the Low Countries, as opposed to les pays de par delà ("the lands over there") for their original homeland: Burgundy in present-day east-central France.[30]

Pays d'embas

In the first half of the 16th century, in the Habsburg Netherlands under Mary, Queen of Hungary, les pays de par deçà developed into pays d'embas ("lands down-here"),[31] a deixic expression in relation to other Habsburg possessions in Europe, particularly mountainous Austria and Hungary. This was translated as Neder-landen in contemporary Dutch official documents.[32]

Niderlant

Since the late Middle Ages, Niderlant (in singular) was also the region between the Meuse and the lower Rhine. The area known as Oberland ("high land") was in this deixic context considered to begin approximately at the nearby higher located Cologne.

Nederlands

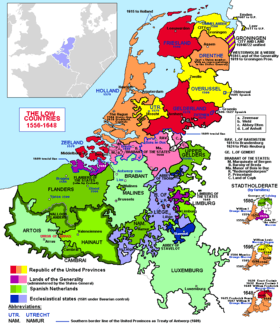

From the mid-sixteenth century on, "Low Countries" or "the Netherlands" became a commonly used name and lost its deixic meaning of a low-lying land as opposed to a high-lying land. But the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) divided the Low Countries into the northern Dutch Republic (Latin: Belgica Foederata) and the southern Spanish Netherlands (Latin: Belgica Regia), introducing a new deixis, i.e. Northern vs. Southern Netherlands, the latter being roughly present-day Belgium. Nederlands, as a name for the language, was first attested in a work printed at Gouda in 1482.[33] Since the 15th century it slowly replaced the above-mentioned nomenclature Diets. Many languages have a calque or cognate derived from Nederlands:

|

Netherlandish

The English adjective "Netherlandish", meaning "from the Netherlands" or "from the Low Countries", derived directly from the Dutch word Nederlands(e). It is typically used in reference to paintings or music produced anywhere in the Low Countries during the 15th and early 16th century, which are collectively called Early Netherlandish painting (Dutch: Vlaamse primitieven, "Flemish primitives" — also common in English before the mid 20th century), or (regarding music) the Netherlandish School.

Later art and artists from the southern Catholic provinces of the Low Countries are usually called Flemish and those from the northern Protestant provinces Dutch, but art historians sometimes use "Netherlandish art" for art of the Low Countries produced before 1830, i.e., until the secession of Belgium from the Netherlands.

"Netherlandish" is sometimes used as well as a general-purpose adjective; e.g., "Northern Netherlandish humanists."[34]

Southern Netherlands

Between 1579 and 1794 a region comprising present Belgium, Luxembourg and parts of northern France was called the Southern Netherlands, also known as the Spanish Netherlands between 1579 and 1713, and the Austrian Netherlands after 1713, after the main possession of their Habsburg lord.

Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands

The Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands (Dutch: Souverein Vorstendom der Verëenigde Nederlanden) was a short-lived sovereign principality and the precursor of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in which it was reunited with the Southern Netherlands in 1815. The principality was proclaimed in 1813 when the victors of the Napoleonic Wars established a political reorganisation of Europe, which would eventually be defined by the Congress of Vienna.

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

Between 1815 and 1830 the Northern Netherlands and the Southern Netherlands (Belgium and Luxembourg) were unified again under King William I as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Kingdom of the Netherlands

Today the Kingdom of the Netherlands encompasses the Netherlands, one constituent country of the Kingdom, Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten. In Dutch common practice, the Kingdom of the Netherlands is shortened to "Kingdom" (Dutch: het Koninkrijk) and not to "Netherlands", as the latter may confuse the Kingdom with the constituent country. The Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands also shortens the Kingdom of the Netherlands in this fashion.[35] Outside the Kingdom, however, "Netherlands" is a common name for the Kingdom of the Netherlands, e.g., as a short name in international organizations or during bilateral meetings.

New Netherland

The Dutch colony centred on New Amsterdam (the modern New York City) was called New Netherland. Today, many cities and neighborhoods in and around New York City have a name originally given by the Dutch and referring to places in the Netherlands, such as Brooklyn (Breukelen), Flushing Meadows (Vlissingen), Harlem (Haarlem) and Hoboken (Hoboken, now in Belgium).

Low Countries

The Low Countries (Dutch: Lage Landen) refers to the historical region de Nederlanden: those principalities located on and near the mostly low-lying land around the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. That region corresponds to all of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, forming the Benelux. The name "Benelux" is formed from joining the first two or three letters of each country's name Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. It was first used to name the customs agreement that initiated the union (signed in 1944) and is now used more generally to refer to the geopolitical and economical grouping of the three countries, while "Low Countries" is used in a more cultural or historical context.

In many languages the nomenclature "Low Countries" can both refer to the cultural and historical region comprising present-day Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, as to "the Netherlands" alone, i.e., Les Pays-Bas in French, Los Países Bajos in Spanish and i Paesi Bassi in Italian. Several other languages have literally translated "Low Countries" in their own language to refer to the Dutch language:

Germania Inferior

Harking back to Roman times when the Low Countries' river estuary was known as Germania Inferior, 16th century lexicographers translate titles of Dutch dictionaries in a variety of Latin names. Cornelis Kiliaan for example, translates his Nederlandsche spraecke (English: Dutch language) with inferior Germanica.[36]

From local polities

Seventeen Provinces

Holland, Flanders and 15 other counties, duchies and bishoprics in the Low Countries were united as the Seventeen Provinces in a personal union during the 16th century, covered by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, which freed the provinces from their archaic feudal obligations.

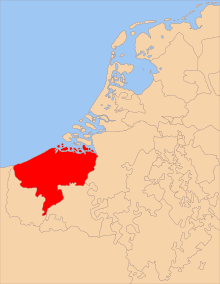

Flanders (pars pro toto)

Flemish (Dutch: Vlaams) is derived from the name of the County of Flanders (Dutch: Graafschap Vlaanderen), in the early Middle Ages the most influential county in the Low Countries, and the residence of the Burgundian dukes. Due to its cultural importance, "Flemish" became in certain languages a pars pro toto for the Low Countries. This was certainly the case in France, since the Flemish are the first Dutch speaking people for them to encounter. In French-Dutch dictionaries of the 16th century, "Dutch" is almost always translated as Flameng.[37]

A calque of Vlaams as a reference to the language of the Low Countries was also in use in Spain. In the 16th century, when Spain inherited the Habsburg Netherlands, the whole area of the Low Countries was indicated as Flandes, and the inhabitants of Flandes were called Flamencos. For example, the Eighty Years' War between the rebellious Dutch Republic and the Spanish Empire was called Las guerras de Flandes.[38]

The English adjective "Flemish" (first attested as flemmysshe, c. 1325;[39] cf. Flæming, c. 1150),[40] was probably borrowed from Old Frisian.[41] The name Vlaanderen was probably formed from a stem flām-, meaning "flooded area", with a suffix -ðr- attached.[42] The Old Dutch form is flāmisk, which becomes vlamesc, vlaemsch in Middle Dutch and Vlaams in Modern Dutch.[43] Flemish is now exclusively used to describe the majority of Dutch dialects found in Flanders, and as a reference to that region. Calques of Vlaams in other languages:

|

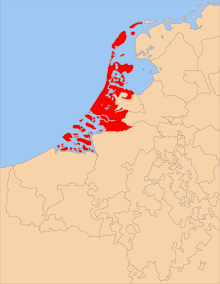

Holland (pars pro toto)

In many languages including English, (a calques of) "Holland" is a common name for the Netherlands as a whole. Even the Dutch use this sometimes. Strictly speaking, Holland is only the central-western region of the country comprising two of the twelve provinces, North Holland and South Holland, and thus linguistically a pars pro toto similar to use of Russia for the (former) Soviet Union, and England for the United Kingdom. The use is sometimes discouraged. For example, the "Holland" entry in the style guide of The Guardian and The Observer newspapers states: "Do not use when you mean the Netherlands (of which it is a region), with the exception of the Dutch football team, which is conventionally known as Holland".[44] The Times style guide states "use the Netherlands ... for all contexts except sports teams, historical uses, or when referring to the provinces of North and South Holland".[45]

Historically the County of Holland was the most powerful region in the current Netherlands. The counts of Holland were also counts of Hainaut, Friesland and Zeeland from the 13th to the 15th centuries. Holland remained most powerful during the period of the Dutch Republic, dominating foreign trade, and hence most of the Dutch traders encountered by foreigners were from Holland, which explains why the Netherlands is often called Holland overseas.[46]

After the demise of the Dutch Republic under Napoleon, that country became known as the Kingdom of Holland (1806–1810), and the former countship of Holland was split up and became two of its eleven provinces, later known as North Holland and South Holland, because one Holland province by itself was considered too dominant in area, population and wealth compared to the other provinces. Today the two provinces making up Holland, including the cities of Amsterdam, The Hague and Rotterdam, remain politically, economically and demographically dominant – 37% of the Dutch population live there. In most other Dutch provinces and also Flanders, the word Hollander is sometimes used in a pejorative sense to refer to the perceived superiority or supposed arrogance of people from the Randstad – the main conurbation of Holland proper and of the Netherlands.

In 2009, members of the First Chamber drew attention to the fact that in Dutch passports, for some EU-languages a translation meaning "Kingdom of Holland" was used, as opposed to "Kingdom of the Netherlands". As replacements for the Estonian Hollandi Kuningriik, Hungarian Holland Királyság, Romanian Regatul Olander and Slovak Holandské král'ovstvo, the parliamentarians proposed Madalmaade Kuningriik, Németalföldi Királyság, Regatul Țărilor de Jos and Nizozemské Král'ovstvo, respectively. Their reasoning was that "if in addition to Holland a recognisable translation of the Netherlands does exist in a foreign language, it should be regarded as the best translation" and that "the Kingdom of the Netherlands has a right to use the translation it thinks best, certainly on official documents".[47] Although the government initially refused to change the text except for the Estonian, recent Dutch passports feature the translation proposed by the First Chamber members. Calques derived from Holland to refer to the Dutch language in other languages:

|

|

Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland (Dutch: Koninkrijk Holland, French: Royaume de Hollande) was set up by Napoleon as a puppet kingdom for his third brother, Louis Bonaparte, in order to better control the Netherlands. The name of the leading province, Holland, was now taken for the whole country. In 1807 Prussian East Frisia and Jever were added to the kingdom. In 1809, after a British invasion, Holland had to give over all territories south of the river Rhine to France.

New Holland

Abel Tasman gave the name New Holland to the continent now known as Australia, a name it retained for 150 years until the United Kingdom renamed it in 1824. Dutch cartographers following Abel Tasman also named New Zealand after the Dutch province Zeeland. There was also a colony called New Holland in South America. Part of Lincolnshire is also known as Holland.

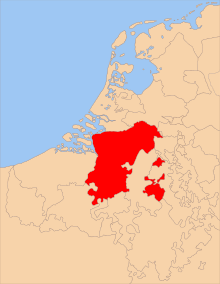

Brabant (pars pro toto)

As the Low Country's prime duchy, with the only and oldest scientific centre (the University of Leuven), Brabant has served as a pars pro toto for the whole of the Netherlands, for example in the writings of Desiderius Erasmus in the early 16th century.[48]

Perhaps of influence for this pars pro toto usage is the Brabantian holding of the ducal title of Lower Lorraine. In 1190, after the death of Godfrey III, Henry I became Duke of Lower Lorraine. However, by that time the title had lost most of its territorial authority. According to protocol, all his successors were thereafter called Dukes of Brabant and Lower Lorraine (often called Duke of Lothier).

Brabant symbolism served again a role as national symbols during the formation Belgium. The national anthem of Belgium is called the Brabançonne (English: "the Brabantian"), and the Belgium flag has taken its colors from the Brabant coat of arms: black, yellow and red. This was influenced by the Brabant Revolution (French: Révolution brabançonne, Dutch: Brabantse Omwenteling), sometimes referred to as the "Belgian Revolution of 1789–90" in older writing, that was an armed insurrection that occurred in the Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) between October 1789 and December 1790. The revolution led to the brief overthrow of Habsburg rule and the proclamation of a short-lived polity, the United Belgian States. Some historians have seen it as a key moment in the formation of a Belgian nation-state, and an influence on the Belgian Revolution of 1830.

From tribes of the pre-Migration Period

Belgae

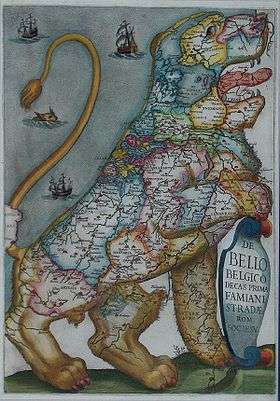

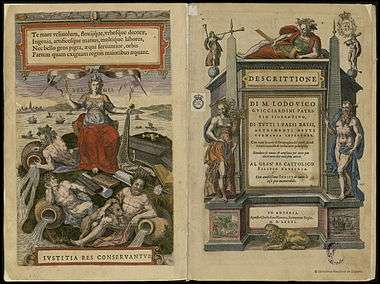

The nomenclature Belgica is harking back to the ancient local tribe of the Belgae and the Roman province named after that tribe Gallia Belgica. Although a derivation of that name is now reserved for the Kingdom of Belgium (the former Southern Netherlands), from the 15th to the 17h century the name was the usual Latin translation to refer to the entire Low Countries, which was on maps sometimes heroically visualised as the Leo Belgicus.[49]

Lingua Belgica

Belgica or Belgicus as the Latinised name for the Dutch language became populair under the influence of Humanism. In the second half of the sixteenth century Belgicus appears frequently in Dutch dictionaries and lexicons, e.g., Dictionarium, colloquia sive formulas quartet linguarum, Belgicae, Gallicae, Hispanicae, Italic (1558).[50]

Belgica Foederata and Belgica Regia

After the northern part of the Low Countries declared its independence from the Spanish Empire, its Latin name was restyled as Belgica Foederata ("United Netherlands", usually called the Dutch Republic in English) for the rebellious northern provinces and Belgica Regia ("Kings' Netherlands") for the southern part that remained faithful to the Spanish king. The latter became in 1830 the kingdom of Belgium.

United Belgian States

The United Belgian States or "United Netherlandish States" (Dutch: Verenigde Nederlandse Staten or Verenigde Belgische Staten, French: États-Belgiques-Unis, Latin: Foederati belgii), also known as the "United States of Belgium", was a confederation in the Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) which was established after the Brabant Revolution. It existed from January to December 1790 as part of the unsuccessful revolt against the Habsburg Emperor, Joseph II.

Batavi

Throughout the centuries the Dutch attempted to define their collective identity by looking at their ancestors, the Batavi. As claimed by the Roman historian Tacitus, the Batavi where a brave Germanic tribe living in the Netherlands, probably in the Betuwe region. In Dutch, the adjective Bataafs ("Batavian") was used from the 15th to the 18th century, meaning "of, or relating to the Netherlands" (but not the southern Netherlands).

lingua Batava

Batavicus and lingua Batava have been in use as Latin names for the Dutch language, albeit not often.[50] In French, a batavisme is a French expression copied from the Dutch language,[51] and a batave is a person from the Netherlands.[52]

Batavian Legion

The Batavian Legion (légion batave or légion franche étrangère batave) was a unit of Dutch volunteers under French command, created and dissolved in 1793.

Batavian Revolution and Batavian Republic

The Batavian Revolution (Dutch: Bataafsche Revolutie) was a political, social and cultural turmoil in the Netherlands at the end of the 18th century. In early 1795, intervention by French revolutionary forces led to the downfall of the old Dutch Republic. The newly proclaimed Batavian Republic (Dutch: Bataafse Republiek; French: République Batave), a name that refers to the Batavians that in Dutch nationalistic lore represented both its ancestry and its ancient quest for liberty, and those of the France, enjoyed widespread support from the Dutch population and was the product of a genuine popular revolution. Though the French presented themselves as liberators,[53] they behaved like conquerors. This changed the Dutch republic from a client state of England and Prussia into a French one. The period of Dutch history that followed the revolution is referred to as the "Batavian-French era" (1795–1813) even though the time spanned was only 20 years, of which three were under French occupation.

Frisii

From confederations of Germanic tribes

Franconian

Frankish was the West Germanic language spoken by the Franks between the 4th and 8th century. Between the fifth and ninth centuries, the languages spoken by the Salian Franks in Belgium and the Netherlands evolved into Old Dutch (Dutch: Oudnederfrankisch), which formed the beginning of a separate Dutch language and is synonymous with Old Dutch. Compare the near-synonymous usage, in a linguistic context, of Old English vs. Anglo-Saxon.

Frisian

Frisii were an ancient tribe who lived in the coastal area of the Netherlands in Roman times. They left the land abandoned due to deteriorating climate conditions. Anglo-Saxons, coming from the east, repopulated the region. Franks in the south, who were familiar with Roman texts, called the coastal region Frisia, and hence its inhabitants "Frisians", even though they had now ancestry with the old Frisii.[54] After a Frisian Kingdom emerged in the mid-7th century in the Netherlands, with its center of power the city of Utrecht,[55] the Franks conquered the Frisians and converted them to Christianity. From that time on a colony of Frisians was living in Rome and thus the old name for the people from the Low Countries who came to Rome has remained in use in the national church of the Netherlands in Rome, which is called the Frisian church (Dutch: Friezenkerk; Italian: chiesa nazionale dei Frisoni). In 1989, this church was granted to the Dutch community in Rome.

See also

References

- ↑ "Low Countries". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ "Low Countries - definition of Low Countries by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia.". Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- 1 2 "Franks". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Lotharingia / Lorraine ( Lothringen )". 5 September 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "1. De landen van herwaarts over". Vre.leidenuniv.nl. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ Alastair Duke. "The Elusive Netherlands. The question of national identity in the Early Modern Low Countries on the Eve of the Revolt". Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006), The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, USA: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-929668-5, p. 269.

- ↑ W. Haubrichs, "Theodiscus, Deutsch und Germanisch - drei Ethnonyme, drei Forschungsbegriffe. Zur Frage der Instrumentalisierung und Wertbesetzung deutscher Sprach- und Volksbezeichnungen." In: H. Beck et al., Zur Geschichte der Gleichung "germanisch-deutsch" (2004), 199–228

- ↑ Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd revised edn., s.v. "Dutch" (Random House Reference, 2005).

- ↑ Roland Willemyns (2013). Dutch: Biography of a Language. Oxford University Press. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 M. Philippa e.a. (2003–2009) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands [diets]

- 1 2 Alice L. Harting-Correa: Walahfrid Strabo's Libellus de Exordiis Et Incrementis Quarundam in ...

- 1 2 Cornelis Dekker: The Origins of Old Germanic Studies in the Low Countries

- ↑ Farmer, David Hugh (1978). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282038-9.

- 1 2 M. Philippa e.a. (2003–2009) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits]

- ↑ L. Weisgerber, Deutsch als Volksname 1953

- ↑ J. de Vries (1971), Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek

- ↑ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ↑ The Pennsylvania Dutch Country, by I. Richman, 2004: "Taking the name Pennsylvania Dutch from a corruption of their own word for themselves, "Deutsch," the first German settlers arrived in Pennsylvania in 1683. By the time of the American Revolution, their influence was such that Benjamin Franklin, among others, worried that German would become the commonwealth's official language."

- ↑ Moon Spotlight Pennsylvania Dutch Country, by A. Dubrovsk, 2004.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Dutch Alphabet, by C. Williamson.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Dutch: A Dialect of South German with an Infusion of English, by S. Stehman, 1872.

- ↑ Powwowing Among the Pennsylvania Dutch, by David W. Kriebe, 2007.

- ↑ The Pennsylvania Journey, by J.A. Davis, 2005.

- ↑ Frans, Claes (1970). "De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw". Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (86): p. 300.

- ↑ Bree, Marijke van der Wal, Cor van (2008). Geschiedenis van het Nederlands (5., bijgewerkte druk. ed.). Houten: Spectrum. ISBN 90-491-0011-2.

- ↑ Toorn, M.C. van den (1980). Nederlandse taalkunde (6. verbeterde druk. ed.). Utrecht: Spectrum. ISBN 978-90-274-5245-0.

- ↑ As based on WNT, Dictionary of the Dutch language, entry Nederduits.

- ↑ Bosworth, Joseph (1848). The Origin of the English, Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Nations: With a Sketch of Their Early Literature. Longman. p. 81fn. Apparently, the etymology of the German word Niedersachsen goes back to this Dutch source; see "Niedersachsen". Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ Peters, Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier ; translated by Elizabeth Fackelman ; translation revised and edited by Edward (1999). The promised lands the Low Countries under Burgundian rule, 1369–1530. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-8122-0070-5.

- ↑ "The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 2, The Reformation, 1520–1559".

- ↑ Van der Lem, Anton. "De Opstand in de Nederlanden 1555–1609;De landen van herwaarts over". Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ Rijpma & Schuringa, Nederlandse spraakkunst, Groningen 1969, p. 20.)

- ↑ The Batavian Myth: A Study Pack from the Department of Dutch, University College London

- ↑ Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands

- ↑ De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw, in: Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde. Jaargang 86. E.J. Brill, Leiden 1970

- ↑ Frans, Claes (1970). "De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw". Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (86): p. 297.

- ↑ Pérez, Yolanda Robríguez (2008). The Dutch Revolt through Spanish eyes : self and other in historical and literary texts of Golden Age Spain (c. 1548–1673) (Transl. and rev. ed.). Oxford: Peter Lang. p. 18. ISBN 3-03911-136-1. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ "entry Flēmish". Middle English Dictionary (MED).

- ↑ "MED, entry "Flēming"". Quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ↑ "entry Flemish". Online Etymological Dictionary. Etymonline.com. which cites Flemische as an Old Frisian form; but cf. "entry FLĀMISK, which gives flēmisk". Oudnederlands Woordenboek (ONW). Gtb.inl.nl.

- ↑ "Entry VLAENDREN; ONW, entry FLĀMINK; Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT), entry VLAMING". Vroeg Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek (VMNW). Gtb.inl.nl.

- ↑ ONW, entry FLĀMISK.

- ↑ "Guardian and Observer style guide: H". The Guardian. London. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ↑ "Online style guide - H". The Times. London. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ↑ "Holland or the Netherlands?". The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ (Dutch) Article on website of First Chamber

- ↑ Prevenier, W.; Uytven, R. van; Poelhekke, J. J.; Bruijn, J. R.; Boogman, J. C.; Bornewasser, J. A.; Hegeman, J. G.; Carter, Alice C.; Blockmans, W.; Brulez, W.; Eenoo, R. van. Acta Historiae Neerlandicae: Studies on the History of The Netherlands VII. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 83–87. ISBN 978-94-011-5948-7.

- ↑ For example, the map "Belgium Foederatum" by Matthaeus Seutter, from 1745, which show the current Netherlands.

- 1 2 Frans, Claes (1970). "De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw". Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (86): p. 296.

- ↑ "Le Dictionnaire - Définition batavisme et traduction". www.le-dictionnaire.com.

- ↑ "Le Dictionnaire - Définition batave et traduction". www.le-dictionnaire.com.

- ↑ Schama, Simon (1992). Patriots and liberators : revolution in the Netherlands, 1780–1813 (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. p. 195. ISBN 0-679-72949-6.

- ↑ Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition, Volume 13 van Amsterdam archaeological studies, redacteurs: Ton Derks, Nico Roymans, Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 90-8964-078-9, pp. 332–333

- ↑ Dijkstra, Menno (2011). Rondom de mondingen van Rijn & Maas. Landschap en bewoning tussen de 3e en 9e eeuw in Zuid-Holland, in het bijzonder de Oude Rijnstreek (in Dutch). Leiden: Sidestone Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-90-8890-078-5.