Black Power movement

| Black Power movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Black Power | |||

|

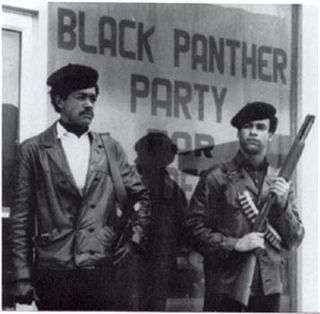

Black Panther founders standing guard with shotguns | |||

| Date | 1960s – 1970s | ||

| Location | United States | ||

| Result |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Part of racial and political series on |

| Black Power |

|---|

|

|

History |

|

Organizations

|

|

The Black Power movement was a political movement to achieve a form of Black Power and the many philosophies it contains. The movement saw various forms of activism some violent and some peaceful, all hoping to achieve black empowerment. The Black Power movement also represented socialist movements, all with the general motivation of improving the standing of black people in society.[1] Originated in the aftershock of the Civil Rights movement, some doubted the philosophy of the movement begging for more radical action, taking influences from Malcolm X. The cornerstone of the movement was the Black Panther Party, a Black Power organization dedicated to socialism and the use of violence to achieve it.[2] The Black Power movement developed in the criticisms of the Civil Rights movement in the early 1960s, and over time and into the 1970s, the movement grew and became more violent. After years of violence, many left the movement and the police began arresting violent actors in the movement.[3] The Black Power movement also spilled out into the Caribbean creating the Black Power Revolution.

Background

The first popular use of the term "Black Power" as a social and racial slogan was by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) and Willie Ricks (later known as Mukasa Dada), both organizers and spokespersons for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). On June 16, 1966, in a speech in Greenwood, Mississippi after the assassination attempt on James Meredith by Aubrey James Norvell during the March Against Fear, Stokely Carmichael used the term.[4][5]

By the late 1960s Black Power came to represent the demand for more immediate violent action to counter American white supremacy. Most of these ideas were influenced by Malcolm X's criticism of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s peaceful protest methods. The 1965 assassination of Malcolm X coupled with the urban uprisings of 1964 and 1965 ignited the Black Power movement. By 1968 Black Power was a recognizable movement with a growing force of people who sympathize. New organizations began to form such as the Black Panther Party each supporting Black Power philosophies ranging from socialism to black nationalism.[6]

History

Beginning in the early 1960s

The organization Nation of Islam began developing a black nationalist movement since the 1930s, inspiring later black nationalist groups. The Nation of Islam continues to function to this day.[7] In the early 1960s the Almighty Black P. Stone Nation gang developed into a Black Power group supporting black nationalism.[8] Malcolm X rose rapidly to become the minister and national spokesperson for the Nation of Islam. Highly influenced by Malcolm X's membership, the Nation claimed a membership of 30,000. In March 1964, Malcolm X was excommunicated from the Nation due to disagreements with Elijah Muhammad; among other things, Malcolm X found issues with Muhammad's adherence to Muslim teachings, and Malcolm X's fame had led to media attention and a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) infiltration into the Nation of Islam.[9] In April 1964, one month later, Malcolm X founded Muslim Mosque Inc., stating, "I never left the Nation of Islam of my own free will. It was they who conspired with Captain Joseph here in New York to pressure me out of the Nation."[10] Malcolm X would later be assassinated in February 1965.[11]

After the Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1965, the civil rights group the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, decided to break their ties with the mainstream civil rights movement and the liberal organizations that supported it. They argued instead that blacks needed to build power of their own rather than seek accommodations from the power structure in place. SNCC migrated from a philosophy of nonviolence to one of greater militancy after the mid-1960s, as an advocate of the burgeoning “black power” movement, a facet of late 20th-century black nationalism.[12] The organization continued its militancy later on and established ties with radical groups such as the Students for a Democratic Society. In late October 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense). In formulating a new politics, they drew on their experiences working with a variety of Black Power organizations.[13]

Escalation in the late 1960s

The initial tactic of the Black Panther Party utilized contemporary open-carry gun laws to protect Party members when policing the police. This act was done in order to record incidents of police brutality by distantly following police cars around neighborhoods.[14] In 1966, Black Panther George Jackson started the marxist Black Guerrilla Family during his time in prison, the group often attacked guards in acts of revolution.[15] Numbers grew slightly starting in February 1967, when the party provided an armed escort at the San Francisco airport for Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow and keynote speaker for a conference held in his honor.[16] By 1967 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began to fall apart due to policy disputes in its leadership and many members left for the Black Panther Party.[17] Throughout 1967 the Panthers staged rallies and disrupted the California State Assembly with armed marchers.[18] In late 1967 the FBI developed COINTELPRO to investigate black nationalist groups and other civil rights leaders.[19] By 1969, the Black Panthers and their allies had become primary COINTELPRO targets, singled out in 233 of the 295 authorized "Black Nationalist" COINTELPRO actions. In the year 1968 the Republic of New Afrika was founded seeking a black nation in the southern United States, only to be ineffective and dissolve in the early 1970s.

By 1968 many Black Panther leaders had been arrested, including founder Huey P. Newton for the murder of a police officer,[20] yet numbers surged. Black Panthers later engaged the police in a fire fight in a Los Angeles gas station. In the same year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated creating the nationwide King assassination riots, the widest wave of social unrest since the American civil war.[21] The King riots were not the only instances of social unrest in the year. In Cleveland, Ohio, in the neighborhood of Glenville the black radical group "Republic of New Libya" engages the police in a firefight. Open rebellion breaks out and militants begin sniping police officers, eventually the militants are neutralized. After the Glenville shootout, rioting began the next day, but was eventually ended.[22] The year also marked the beginning of the White Panther Party a group of whites dedicated to the cause of the black panthers. Meanwhile, in Trinidad the black power movement was growing, forming organizations and staging marches. Plamondon the founder of the White Panther Party was indicted fellow founder Sinclair in connection to the bombing of a Central Intelligence Agency office in Ann Arbor on September 29, 1968.[23]

By 1969 the Black Panthers begin purging members due to fear of law enforcement infiltration, and engage in multiple gun fights with police and one with a black nationalist organization. The Black Panthers also continue their "Free Huey" campaign internationally in an attempt to free their founder from jail. In the spirit rising of militancy the League of Revolutionary Black Workers forms in Detroit which supported labor rights and black liberation.

Peak in the early 1970s

.jpg)

In 1970 Black Panther founder Huey P. Newton is released from prison and travels to many communist countries to discuss methods to fight the American government. The panthers also ambush police officers and unsuccessfully attempt to kill them. In Trinidad the black power movement had escalated into the Black Power Revolution in which many Afro-Trinidadians forced the government of Trinidad to give into reforms. Later many panthers visited Algeria to discuss Pan-Africanism and anti-imperialism. In the year it is believed former Black Panthers including Eldridge Cleaver, formed the Black Liberation Army to continue a violent revolution rather than the party's new reform movements.[24] On October 22, 1970, the Black Liberation Army is believed to have planted a bomb in St. Brendan's Church in San Francisco while it was full of mourners attending the funeral of San Francisco police officer Harold Hamilton, who had been killed in the line of duty while responding to a bank robbery. The bomb was detonated, but no one in the church suffered serious injuries.[25]

In 1971 several Panther officials were forced to flee the US due to police concerns. 1971 was the only active year of the Black Revolutionary Assault Team, a group that bombed the New York South African consular office, the second and final action took place on September 20, 1971 when it placed bombs at the UN Missions of Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) and the Republic of Malawi.[26] In February 1971, ideological splits within the Black Panther Party between leaders Newton and Cleaver eventually led to two factions within the party; the conflict turned violent and four people were killed in a series of assassinations.[27] On May 21, 1971, as many as five Black Liberation Army members participated in the shootings of two New York City police officers, Joseph Piagentini and Waverly Jones. Those arrested and brought to trial for the shootings include Anthony Bottom (aka Jalil Muntaqim), Albert Washington, Francisco Torres, Gabriel Torres, and Herman Bell. During the jail sentence of White Panther John Sinclair a "Free John" concert took place, performers included John Lennon and Stevie Wonder, Sinclair was released two days later. On August 29, 1971, three armed BLA members murdered 51-year-old San Francisco police sergeant John Victor Young while he was working at a desk in his police station, which was almost empty at the time due to a bombing attack on a bank that took place earlier - only one other officer and a civilian clerk were there. Two days later, the San Francisco Chronicle received a letter signed by the BLA claiming responsibility for the attack. Late in the year Black Panther Newton visited China for meetings on Maoist theory and anti-imperialism.[28] Black Power icon George Jackson attempted to escape from Prison in August, he killed many guards only to be killed later.[29] Jackson's death triggered the Attica Prison uprising which was latter ended in a bloody siege. On November 3, 1971, Officer James R. Greene of the Atlanta Police Department was shot and killed in his patrol van at a gas station by Black Liberation Army members. His wallet, badge, and weapon were taken, and the evidence at the scene pointed to two suspects. The first was Twymon Meyers, who was killed in a police shootout in 1973, and the second was Freddie Hilton (aka Kamau Sadiki), who evaded capture until 2002, when he was arrested in New York on a separate charge, and was recognized as one of the men wanted in the Greene murder. Apparently, the two men had attacked the officer to gain standing with their compatriots within Black Liberation Army.[30]

1972 was the year Newton shut down many Black Panther chapters and held a party meeting in Oakland. On January 27, 1972 the Black Liberation Army assassinated police officers Gregory Foster and Rocco Laurie at the corner of 174 Avenue B in New York City. After the killings, a note sent to authorities portrayed the murders as a retaliation for the prisoner deaths during 1971 Attica prison riot. To date no arrests have been made. The White Panthers also led many legal reforms in the court system, reforms tackled topics of police surveillance and marijuana law. In the same year MOVE was founded and engaged in demonstrations for environmentalism and black power.[31] On July 31, 1972, five armed Black Liberation Army members hijacked Delta Air Lines Flight 841 en route from Detroit to Miami, eventually collecting a ransom of $1 million and diverting the plane, after passengers were released, to Algeria. The authorities there seized the ransom but allowed the group to flee. Four were eventually caught by French authorities in Paris, where they were convicted of various crimes, but one—George Wright—remained a fugitive until September 26, 2011, when he was captured in Portugal.[32] Portuguese courts rejected the initial pledge for extradition. American authorities may still appeal from this decision. Donald DeFreeze escaped prison in 1973 and forms the Symbionese Liberation Army, later in that year two symbionese members gun down a school superintendent with cyanide bullets.[33] After a murder of a prostitute in 1974 by Black Panther leader Newton, he had to flee the country to Cuba. Elaine Brown becomes party leader and embarks on an election campaign rather than a violent campaign.[34] The Symbionese executed the kidnapping of celebrity Patty Hearst in February 4, 1974, she later joined the group.[35] During Hearst's membership in the group the group executed the Hibernia Bank robbery a Los Angeles police shootout and the Crocker Bank robbery. After Hearst's capture the group fell apart and over the years many members were captured by the police.

Deescalation in the late 1970s

In the late 1970s a rebel group named after a fallen black panther formed named the George Jackson Brigade. From March 1975 to December 1977, the George Jackson Brigade robbed at least seven banks and detonated about 20 pipe bombs—mainly targeting government buildings, electric power facilities, Safeway stores, and companies accused of racism. In 1977, Newton returned from exile in Cuba. Shortly afterward, Elaine Brown resigned from the party and fled to LA.[36] The Party later fell apart leaving only a few members. The last party action will be the murder of a court witness against party leader Newton.[37] MOVE became a commune based living group, when police raided their commune house a firefight broke out one officer was killed, seven other police officers, five firefighters, three MOVE members, and three bystanders were also injured.[38] In another high-profile incident of the Black Liberation Army, Assata Shakur, Zayd Shakur and Sundiata Acoli were said to have opened fire on state troopers in New Jersey after being pulled over for a broken taillight. Zayd Shakur and state trooper Werner Foerster were both killed during the exchange. Following her capture, Assata Shakur was tried in six different criminal trials. According to Shakur, she was beaten and tortured during her incarceration in a number of different federal and state prisons. The charges ranged from kidnapping to assault and battery to bank robbery. Assata Shakur was found guilty of the murder of both Foerster and her companion Zayd Shakur, but escaped prison in 1979 and eventually fled to Cuba and received political asylum. Acoli was convicted of killing Foerster and sentenced to life in prison.

In 1978 a group of Black Liberation Army and Weather Underground members formed named the May 19th Communist Organization, or M19co. It also included members of the Black Panthers and the Republic of New Africa (RNA).[39] [40] In 1979 three M19co members walked into the visitor’s center at the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women near Clinton, took two guards hostage, and freed Assata Shakur, a member of the Black Liberation Army. Shakur was serving a sentence of life plus 26 to 33 years for the murder of a state trooper.[39] Several months later the May 19th Communist Organization arranged for the escape of William Morales, a member of the Puerto Rican separatist group, the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriqueña (FALN), from Bellevue Hospital in New York City where he was recovering after a bomb he was building exploded in his hands.[39]

Decline in the 1980s

Over the 1980s the black power movement continued but after a decline in popularity and membership in organizations. The Black Liberation Army was active in the US until at least 1981 when a Brinks truck robbery, conducted with support from former Weather Underground members Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert, left a guard and two police officers dead. Boudin and Gilbert, along with several BLA members, were subsequently arrested.[41] The May 19th Communist Organization engaged in a bombing campaign in the 1980s. On the 28th of January, 1983, M19co bombed the federal building on Staten Island. On April 25, 1983, M19co committed a bombing at the National War College at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.. November 7,saw the 1983 US Senate Bombing by M19co. On August 18, 1983, M19co bombed Washington Navy Yard Computer Center. Later, on April 5, 1984, M19co bombed the Israeli Aircraft Industries Building. April 20, 1984 saw a M19co bombing at the Washington Navy Yard Officers Club. On November 3, 1984, two members of the M19CO, Susan Rosenberg and Timothy Blunk, were arrested at a mini-warehouse they had rented in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Police recovered more than 100 blasting caps, nearly 200 sticks of dynamite, more than 100 cartridges of gel explosive, and 24 bags of blasting agent from the warehouse. On September 26, 1984, M19co bombed the South African consulate in the United States. The M19co alliance’s last bombing was on February 23, 1985, at the Policemen’s Benevolent Association in New York City.

MOVE had relocated in Philadelphia after their earlier shootout, residents began filing noise complaints and many members where also arrested on unrelated matters. On May 13, 1985, the police, along with city manager Leo Brooks, arrived in force with arrest warrants and attempted to clear the building and arrest the indicted MOVE members.[42] This led to an armed standoff with police,[43] who lobbed tear gas canisters at the building. MOVE members fired at the police, who returned fire with automatic weapons.[44] Commissioner Sambor then ordered that the compound be bombed.[44] From a Pennsylvania State Police helicopter, Philadelphia Police Department Lt. Frank Powell proceeded to drop two one-pound bombs (which the police referred to as "entry devices"[42]) made of FBI-supplied water gel explosive, a dynamite substitute, targeting a fortified, bunker-like cubicle on the roof of the house.[45]

In the late year of 1989 the New Black Panther Party formed. In the same year on August 22, co-founder and leader of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, Huey P. Newton was fatally shot outside 1456 9th St in West Oakland by 24-year-old Black Guerilla Family member, Tyrone Robinson.[46]

Today

After the 1970s the Black Power movement saw a decline but not an end. Since the 1980s black power actions have been rare but not gone. In the year 1998 the Black Radical Congress was founded, with debatable effects. The only popular black power organization that is still in existence and active is the New Black Panther Party. The Black Riders Liberation Party was created by Bloods and Crips gang members as an attempt to recreate the Black Panther Party in 1996. The group has spread, creating chapters in cities across the United States, and frequently staging paramilitary marches.[47] During the 2008 presidential election New Black Panther Party members were accused of voter intimidation at a polling station in a predominantly African-American, Democratic voting district of Philadelphia.[48] After the politically upsetting shooting of Trayvon Martin black power paramilitaries formed, including the Huey P. Newton Gun Club and the New Black Liberation Militia, all staging armed marches and military training. During the Baltimore riots of 2015, Baltimore police claimed that the Black Guerrilla Family, the Bloods, and the Crips were "teaming up" to target police officers.[49] Later, however, leaders of both the Bloods and the Crips denied the allegations,[50] released a video statement asking for calm and peaceful protest in the area,[51] and joined with police and clergy to enforce the curfew.[52] At one occasion, gang members helped to prevent a riot at the Security Square Mall by dispersing attempted rioters.[53] On other occasions, rival gang members helped each other to protect black-owned businesses, black children, and reporters, diverting rioters to Chinese- and Arab-owned businesses instead.[54]

Some have compared the modern movement Black Lives Matter to the Black Power movement, noting its similarities.[55]

Media

Just as Black Power activists focused on community control of schools and politics, the movement took a major interest in creating and controlling its own media institutions. Most famously, the Black Panther Party produced the Black Panther newspaper, which proved to be one of the BPP's most influential tools for disseminating its message and recruiting new members.

In Durham, North Carolina, several young African Americans launched the first ever public, community-based black radio station in September 1971. WAFR catered to Durham’s black listeners with politically engaged, Black Power programming that included jazz, funk, African music, selected local and national news, and even an African American take on Sesame Street’s Children’s Radio Workshop, called the Community Radio Workshop. The station interviewed Black Power activists like Bobby Seale, Howard Fuller, and other Black leftists like Ron Dellums. Unlike previous African American non-commercial radio stations, WAFR was independent, and not based at a university or other pre-existing institution. Key WAFR staffers included Robert Spruill, Obataiye Akinwole, Ralph Williams, Donald Baker, and Kwame and Mary McDonald. Although the station ceased broadcasting in 1976, its influence lives on in other activists radio stations it anticipated, including WPFW in Washington, D.C. and WRFG in Atlanta.[56]

See also

- Abolitionism

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–68)

- Chicano Movement

- Civil rights movements

- History of the socialist movement in the United States

- Marxism–Leninism

- Nation of Islam

- New Left

- Protests of 1968

- Red Power movement

- The Troubles

References

- ↑ Komozi Woodard, "Rethinking the Black Power Movement", Africana Age.

- ↑ "The Black Power Movement 1968-1980", In Search of African America: One Collector's Experience, January 17–March 21, 2004.

- ↑ Peniel E. Joseph, "The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field", The Journal of American History, December 2009, pp. 751–776.

- ↑ Hasan Jeffries (2010). Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama's Black Belt. NYU Press. p. 187.

- ↑ Matthew Duncan: "Black Power salute by John Dominis-1968". matthewduncan07, The Chateau Theme, November 7, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Black_power_movement.aspx

- ↑ Muhammad, Tynetta. "Nation of Islam History". Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ↑ Robert W. Dart, "Views from the Field: The Future is Here Today: Street Gang Trends," Journal of Gang Research 1.1 (1992), 87-90.

- ↑ "Malcolm X". The Estate of Malcolm X. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.brothermalcolm.net/mxwords/letters/lettertoelijah.gif

- ↑ Kihss, Peter (February 22, 1965). "Malcolm X Shot to Death at Rally Here". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2014. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ [http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/569887/Student-Nonviolent-Coordinating-Committee-SNCC>. "Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)"]. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ↑ Seale, 1970, part I; Newton, 1973, parts 2-3; Bloom and Martin, 2013, chapter 1; Murch, 2010, part II and chapter 5.

- ↑ Bloom and Martin, 45.

- ↑ Jackson, George (1994). Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. Chicago Review Press. p. 16. ISBN 1613742894.

- ↑ Black Panther Newspaper, May 15, 1967, p. 3. Bloom and Martin, 71–72.

- ↑ C. Gerald Fraser, "SNCC Has Lost Much of Its Power to Black Panthers", New York Times news service (Eugene Register-Guard), October 9, 1968.

- ↑ Pearson, 129.

- ↑ Stohl, 249.

- ↑ "Police Officer John F. Frey". The Officer Down Memorial Page (ODMP). Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ↑ Peter B. Levy, Baltimore '68, p. 6

- ↑ "Glenville Shootout – The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. A joint effort by Case Western University and the Western Reserve Historical Society. March 27, 1998. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ↑ Zbrozek, C (October 24, 2006). "The bombing of the A2 CIA office". Michigan Daily. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Marie-Agnès Combesque, "Caged panthers", Le Monde diplomatique, 2005.

- ↑ Van Derbeken and Lagos. "Ex-militants charged in S.F. police officer's '71 slaying at station", San Francisco Chronicle (January 23, 2007).

- ↑ Edward F. Mickolaus, Transnational Terrorism: a chronology of events, Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1980, p. 258.

- ↑ Donald Cox, "Split in the Party", New Political Science, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1999.

- ↑ Revolutionary Suicide Penguin classics Delux Edition" page 352

- ↑ "Attempted Escape At San Quentin Leaves Six Dead". Bangor Daily News. Bangor, Maine. UPI. August 23, 1971. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ Fulton Co. District Attorney Report

- ↑ Louise Leaphart James (2013). John Africa...Childhood Untold Until Today. Xlibris Corporation. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Man who escaped from N.J. prison 41 years ago is captured in Portugal". NJ.com. September 26, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Oakland Bullets Had Cyanide". The Washington Post. November 11, 1973. p. A2. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

Investigators say bullets used in the murder of Oakland's school superintendent contained cyanide. Roland Prahl, chief investigator for the Alameda County coroner's office, said Friday that five slugs recovered during the autopsy on the superintendent, Marcus Foster, had the "distinctive odor of cyanide." A coroner's report verified the presence of the poison.

- ↑ Perkins, Margo V. Autobiography As Activism: Three Black Women of the Sixties, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst. PBS. Retrieved on January 21, 2007.

- ↑ Brown, 444–50.

- ↑ Turner, Wallace (December 14, 1977). "Coast Inquiries Pick Panthers As Target; Murder, Attempted Murders and Financing of Poverty Programs Under Oakland Investigation". New York Times.

- ↑ "Nose to Nose: Philadelphia confronts a cult". TIME magazine. August 14, 1978. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- 1 2 3 LEFT-WING EXTREMISM: The Current Threat Prepared for U.S. Department of Energy Office of Safeguards and Security (PDF). Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education: Center for Human Reliability Studies ORISE 01-0439. 2001. p. 1. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ↑ National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and the Responses to Terrorism, DHS (March 1, 2008). "Terrorist Organization Profile: May 19 Communist Order". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and the Responses to Terrorism. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ↑ CourtTV Crime Library, Ambush: The Brinks Robbery of 1981 Archived February 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Shapiro, Michael J (June 17, 2010). The Time of the City: Politics, Philosophy and Genre. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 9781136977879.

- ↑ Account of 1985 incident from USA Today.

- 1 2 Stevens, William K. (May 14, 1985). "Police Drop Bomb on Radicals' Home in Philadelphia". New York Times. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ↑ Trippett, Frank (May 27, 1985). "It Looks Just Like a War Zone". TIME. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Suspect Admits Shooting Newton, Police Say". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1989. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

The police said late Friday that an admitted drug dealer had acknowledged killing Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party

- ↑ http://www.workers.org/ww/1999/aryana1125.php

- ↑ "Republicans Push For New Black Panther Hearing". CBS News, July 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Baltimore police say gangs 'teaming up' to take out officers". The Baltimore Sun. April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Porter, Tom (April 28, 2015). "Bloods and Crips gangs reject claims of kill-a-cop pact". International Business Times. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Gangs call for calm in Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ↑ Berman, John; Castillo, Mariano (April 28, 2015). "Baltimore gangs will help enforce curfew". CNN. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ↑ Haake, Garrett W. (April 28, 2015). "Gang members help prevent riot at Baltimore mall". WUSA. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ↑ Nixon, Ron (April 27, 2015). "Amid Violence, Factions and Messages Converge in a Weary and Unsettled Baltimore". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "From Black Power to Black Lives Matter", We Are Many.

- ↑ Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights and Black Power in the American South

- Brian Meeks, Radical Caribbean: From Black Power to Abu Bakr.

- RNA. A People's Struggle. RNA, Box 90604, Washington, D.C. 20090-0604.

- James A. Geschwender. Class, Race, and Worker Insurgency: The League of Revolutionary Black Workers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

- The documentary film MC5: A True Testimonial (2002) features comments by Sinclair and MC5 on the party.

- Austin, Curtis J. (2006). Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-827-5

- McLellan, Vin, and Paul Avery. The Voices of Guns: The Definitive and Dramatic Story of the Twenty-two-month Career of the Symbionese Liberation Army. New York: Putnam, 1977.