Forbidden City

|

The Gate of Divine Might, the northern gate. The lower tablet reads "The Palace Museum" (故宫博物院) | |

Location within China | |

| Established | 1922 |

|---|---|

| Location | 4 Jingshan Front St, Dongcheng, Beijing,China |

| Coordinates | 39°54′58″N 116°23′53″E / 39.915987°N 116.397925°E |

| Type | Art museum, Imperial Palace, Historic site |

| Visitors |

14 million Ranking 1st globally |

| Curator | Shan Jixiang (单霁翔) |

| Built | 1406–1420 |

| Architect | Kuai Xiang (蒯祥) |

| Architectural style(s) | Chinese architecture |

| Website |

www |

| Forbidden City | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Forbidden City" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 紫禁城 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | "Purple [North Star] Forbidden City" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Forbidden City was the Chinese imperial palace from the Ming dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty—the years 1420 to 1912. It is located in the centre of Beijing, China, and now houses the Palace Museum. It served as the home of emperors and their households as well as the ceremonial and political centre of Chinese government for almost 500 years.

Constructed from 1406 to 1420, the complex consists of 980 buildings[1] and covers 72 ha (over 180 acres).[2][3] The palace complex exemplifies traditional Chinese palatial architecture,[4] and has influenced cultural and architectural developments in East Asia and elsewhere. The Forbidden City was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987,[4] and is listed by UNESCO as the largest collection of preserved ancient wooden structures in the world.

Since 1925, the Forbidden City has been under the charge of the Palace Museum, whose extensive collection of artwork and artefacts were built upon the imperial collections of the Ming and Qing dynasties. Part of the museum's former collection is now located in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Both museums descend from the same institution, but were split after the Chinese Civil War. With over 14.6 million annual visitors, the Palace Museum is the most visited Museum in the world.[5]

Name

| Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 439 |

| UNESCO region | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Extensions | 2004 |

The common English name, "the Forbidden City", is a translation of the Chinese name Zijin Cheng (Chinese: 紫禁城; pinyin: Zíjinchéng; literally: "Forbidden City"). The name Zijin Cheng first formally appeared in 1576.[6] Another English name of similar origin is "Forbidden Palace".[7]

The name "Zijin Cheng" is a name with significance on many levels. Zi, or "Purple", refers to the North Star, which in ancient China was called the Ziwei Star, and in traditional Chinese astrology was the heavenly abode of the Celestial Emperor. The surrounding celestial region, the Ziwei Enclosure (Chinese: 紫微垣; pinyin: Zǐwēiyuán), was the realm of the Celestial Emperor and his family. The Forbidden City, as the residence of the terrestrial emperor, was its earthly counterpart. Jin, or "Forbidden", referred to the fact that no one could enter or leave the palace without the emperor's permission. Cheng means a city.[8]

Today, the site is most commonly known in Chinese as Gùgōng (故宫), which means the "Former Palace".[9] The museum which is based in these buildings is known as the "Palace Museum" (Chinese: 故宫博物院; pinyin: Gùgōng Bówùyùan).

History

When Hongwu Emperor's son Zhu Di became the Yongle Emperor, he moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, and construction began in 1406 on what would become the Forbidden City.[8]

Construction lasted 14 years and required more than a million workers.[10] Material used include whole logs of precious Phoebe zhennan wood (Chinese: 楠木; pinyin: nánmù) found in the jungles of south-western China, and large blocks of marble from quarries near Beijing.[11] The floors of major halls were paved with "golden bricks" (Chinese: 金砖; pinyin: jīnzhuān), specially baked paving bricks from Suzhou.[10]

From 1420 to 1644, the Forbidden City was the seat of the Ming dynasty. In April 1644, it was captured by rebel forces led by Li Zicheng, who proclaimed himself emperor of the Shun dynasty.[12] He soon fled before the combined armies of former Ming general Wu Sangui and Manchu forces, setting fire to parts of the Forbidden City in the process.[13]

By October, the Manchus had achieved supremacy in northern China, and a ceremony was held at the Forbidden City to proclaim the young Shunzhi Emperor as ruler of all China under the Qing dynasty.[14] The Qing rulers changed the names on some of the principal buildings, to emphasise "Harmony" rather than "Supremacy",[15] made the name plates bilingual (Chinese and Manchu),[16] and introduced Shamanist elements to the palace.[17]

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, Anglo-French forces took control of the Forbidden City and occupied it until the end of the war.[18] In 1900 Empress Dowager Cixi fled from the Forbidden City during the Boxer Rebellion, leaving it to be occupied by forces of the treaty powers until the following year.[18]

After being the home of 24 emperors – 14 of the Ming dynasty and 10 of the Qing dynasty – the Forbidden City ceased being the political centre of China in 1912 with the abdication of Puyi, the last Emperor of China. Under an agreement with the new Republic of China government, Puyi remained in the Inner Court, while the Outer Court was given over to public use,[19] until he was evicted after a coup in 1924.[20] The Palace Museum was then established in the Forbidden City in 1925.[21] In 1933, the Japanese invasion of China forced the evacuation of the national treasures in the Forbidden City.[22] Part of the collection was returned at the end of World War II,[23] but the other part was evacuated to Taiwan in 1948 under orders by Chiang Kai-shek, whose Kuomintang was losing the Chinese Civil War. This relatively small but high quality collection was kept in storage until 1965, when it again became public, as the core of the National Palace Museum in Taipei.[24]

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, some damage was done to the Forbidden City as the country was swept up in revolutionary zeal.[25] During the Cultural Revolution, however, further destruction was prevented when Premier Zhou Enlai sent an army battalion to guard the city.[26]

The Forbidden City was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987 by UNESCO as the "Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties",[27] due to its significant place in the development of Chinese architecture and culture. It is currently administered by the Palace Museum, which is carrying out a sixteen-year restoration project to repair and restore all buildings in the Forbidden City to their pre-1912 state.[28]

In recent years, the presence of commercial enterprises in the Forbidden City has become controversial.[29] A Starbucks store that opened in 2000 sparked objections and eventually closed on 13 July 2007.[30][31] Chinese media also took notice of a pair of souvenir shops that refused to admit Chinese citizens in order to price-gouge foreign customers in 2006.[32]

Description

|

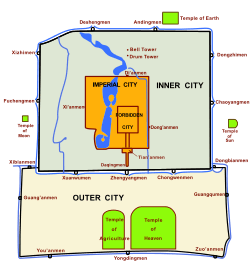

A. Meridian Gate B. Gate of Divine Might C. West Glorious Gate D. East Glorious Gate E. Corner towers F. Gate of Supreme Harmony G. Hall of Supreme Harmony |

H. Hall of Military Eminence J. Hall of Literary Glory K. Southern Three Places L. Palace of Heavenly Purity M. Imperial garden N. Hall of Mental Cultivation O. Palace of Tranquil Longevity |

The Forbidden City is a rectangle, with 961 metres (3,153 ft) from north to south and 753 metres (2,470 ft) from east to west.[2][3] It consists of 980 surviving buildings with 8,886 bays of rooms.[33][34] A common myth states that there are 9,999 rooms including antechambers,[35] based on oral tradition, and it is not supported by survey evidence.[36] The Forbidden City was designed to be the centre of the ancient, walled city of Beijing. It is enclosed in a larger, walled area called the Imperial City. The Imperial City is, in turn, enclosed by the Inner City; to its south lies the Outer City.

The Forbidden City remains important in the civic scheme of Beijing. The central north–south axis remains the central axis of Beijing. This axis extends to the south through Tiananmen gate to Tiananmen Square, the ceremonial centre of the People's Republic of China, and on to Yongdingmen. To the north, it extends through Jingshan Hill to the Bell and Drum Towers.[37] This axis is not exactly aligned north–south, but is tilted by slightly more than two degrees. Researchers now believe that the axis was designed in the Yuan dynasty to be aligned with Xanadu, the other capital of their empire.[38]

Walls and gates

The Forbidden City is surrounded by a 7.9 metres (26 ft) high city wall[15] and a 6 metres (20 ft) deep by 52 metres (171 ft) wide moat. The walls are 8.62 metres (28.3 ft) wide at the base, tapering to 6.66 metres (21.9 ft) at the top.[39] These walls served as both defensive walls and retaining walls for the palace. They were constructed with a rammed earth core, and surfaced with three layers of specially baked bricks on both sides, with the interstices filled with mortar.[40]

At the four corners of the wall sit towers (E) with intricate roofs boasting 72 ridges, reproducing the Pavilion of Prince Teng and the Yellow Crane Pavilion as they appeared in Song dynasty paintings.[40] These towers are the most visible parts of the palace to commoners outside the walls, and much folklore is attached to them. According to one legend, artisans could not put a corner tower back together after it was dismantled for renovations in the early Qing dynasty, and it was only rebuilt after the intervention of carpenter-immortal Lu Ban.[15]

The wall is pierced by a gate on each side. At the southern end is the main Meridian Gate (A).[41] To the north is the Gate of Divine Might (B), which faces Jingshan Park. The east and west gates are called the "East Glorious Gate" (D) and "West Glorious Gate" (C). All gates in the Forbidden City are decorated with a nine-by-nine array of golden door nails, except for the East Glorious Gate, which has only eight rows.[42]

The Meridian Gate has two protruding wings forming three sides of a square (Wumen, or Meridian Gate, Square) before it.[43] The gate has five gateways. The central gateway is part of the Imperial Way, a stone flagged path that forms the central axis of the Forbidden City and the ancient city of Beijing itself, and leads all the way from the Gate of China in the south to Jingshan in the north. Only the Emperor may walk or ride on the Imperial Way, except for the Empress on the occasion of her wedding, and successful students after the Imperial Examination.[42]

Outer Court or the Southern Section

Traditionally, the Forbidden City is divided into two parts. The Outer Court (外朝) or Front Court (前朝) includes the southern sections, and was used for ceremonial purposes. The Inner Court (内廷) or Back Palace (后宫) includes the northern sections, and was the residence of the Emperor and his family, and was used for day-to-day affairs of state. (The approximate dividing line shown as red dash in the plan above.) Generally, the Forbidden City has three vertical axes. The most important buildings are situated on the central north–south axis.[42]

Entering from the Meridian Gate, one encounters a large square, pierced by the meandering Inner Golden Water River, which is crossed by five bridges. Beyond the square stands the Gate of Supreme Harmony (F). Behind that is the Hall of Supreme Harmony Square.[44] A three-tiered white marble terrace rises from this square. Three halls stand on top of this terrace, the focus of the palace complex. From the south, these are the Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿), the Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿), and the Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿).[45]

The Hall of Supreme Harmony (G) is the largest, and rises some 30 metres (98 ft) above the level of the surrounding square. It is the ceremonial centre of imperial power, and the largest surviving wooden structure in China. It is nine bays wide and five bays deep, the numbers 9 and 5 being symbolically connected to the majesty of the Emperor.[46] Set into the ceiling at the centre of the hall is an intricate caisson decorated with a coiled dragon, from the mouth of which issues a chandelier-like set of metal balls, called the "Xuanyuan Mirror".[47] In the Ming dynasty, the Emperor held court here to discuss affairs of state. During the Qing dynasty, as Emperors held court far more frequently, a less ceremonious location was used instead, and the Hall of Supreme Harmony was only used for ceremonial purposes, such as coronations, investitures, and imperial weddings.[48]

The Hall of Central Harmony is a smaller, square hall, used by the Emperor to prepare and rest before and during ceremonies.[49] Behind it, the Hall of Preserving Harmony, was used for rehearsing ceremonies, and was also the site of the final stage of the Imperial examination.[50] All three halls feature imperial thrones, the largest and most elaborate one being that in the Hall of Supreme Harmony.[51]

At the centre of the ramps leading up to the terraces from the northern and southern sides are ceremonial ramps, part of the Imperial Way, featuring elaborate and symbolic bas-relief carvings. The northern ramp, behind the Hall of Preserving Harmony, is carved from a single piece of stone 16.57 metres (54.4 ft) long, 3.07 metres (10.1 ft) wide, and 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) thick. It weighs some 200 tonnes and is the largest such carving in China.[10] The southern ramp, in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, is even longer, but is made from two stone slabs joined together – the joint was ingeniously hidden using overlapping bas-relief carvings, and was only discovered when weathering widened the gap in the 20th century.[52]

In the south west and south east of the Outer Court are the halls of Military Eminence (H) and Literary Glory (J). The former was used at various times for the Emperor to receive ministers and hold court, and later housed the Palace's own printing house. The latter was used for ceremonial lectures by highly regarded Confucian scholars, and later became the office of the Grand Secretariat. A copy of the Siku Quanshu was stored there. To the north-east are the Southern Three Places (南三所) (K), which was the residence of the Crown Prince.[44]

Inner Court or the Northern Section

The Inner Court is separated from the Outer Court by an oblong courtyard lying orthogonal to the City's main axis. It was the home of the Emperor and his family. In the Qing dynasty, the Emperor lived and worked almost exclusively in the Inner Court, with the Outer Court used only for ceremonial purposes.[53]

At the centre of the Inner Court is another set of three halls (L). From the south, these are the Palace of Heavenly Purity (乾清宮), Hall of Union, and the Palace of Earthly Tranquility. Smaller than the Outer Court halls, the three halls of the Inner Court were the official residences of the Emperor and the Empress. The Emperor, representing Yang and the Heavens, would occupy the Palace of Heavenly Purity. The Empress, representing Yin and the Earth, would occupy the Palace of Earthly Tranquility. In between them was the Hall of Union, where the Yin and Yang mixed to produce harmony.[54]

The Palace of Heavenly Purity is a double-eaved building, and set on a single-level white marble platform. It is connected to the Gate of Heavenly Purity to its south by a raised walkway. In the Ming dynasty, it was the residence of the Emperor. However, beginning from the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty, the Emperor lived instead at the smaller Hall of Mental Cultivation (N) to the west, out of respect to the memory of the Kangxi Emperor.[15] The Palace of Heavenly Purity then became the Emperor's audience hall.[55] A caisson is set into the roof, featuring a coiled dragon. Above the throne hangs a tablet reading "Justice and Honour" (Chinese: 正大光明; pinyin: zhèngdàguāngmíng).[56]

The Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤寧宮) is a double-eaved building, 9 bays wide and 3 bays deep. In the Ming dynasty, it was the residence of the Empress. In the Qing dynasty, large portions of the Palace were converted for Shamanist worship by the new Manchu rulers. From the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor, the Empress moved out of the Palace. However, two rooms in the Palace of Earthly Harmony were retained for use on the Emperor's wedding night.[57]

Between these two palaces is the Hall of Union, which is square in shape with a pyramidal roof. Stored here are the 25 Imperial Seals of the Qing dynasty, as well as other ceremonial items.[58]

Behind these three halls lies the Imperial Garden (M). Relatively small, and compact in design, the garden nevertheless contains several elaborate landscaping features.[59] To the north of the garden is the Gate of Divine Might.

Directly to the west is the Hall of Mental Cultivation (N). Originally a minor palace, this became the de facto residence and office of the Emperor starting from Yongzheng. In the last decades of the Qing dynasty, empresses dowager, including Cixi, held court from the eastern partition of the hall. Located around the Hall of Mental Cultivation are the offices of the Grand Council and other key government bodies.[60]

The north-eastern section of the Inner Court is taken up by the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (寧壽宮) (O), a complex built by the Qianlong Emperor in anticipation of his retirement. It mirrors the set-up of the Forbidden City proper and features an "outer court", an "inner court", and gardens and temples. The entrance to the Palace of Tranquil Longevity is marked by a glazed-tile Nine Dragons Screen.[61] This section of the Forbidden City is being restored in a partnership between the Palace Museum and the World Monuments Fund, a long-term project expected to finish in 2017.[62]

Religion

Religion was an important part of life for the imperial court. In the Qing dynasty, the Palace of Earthly Harmony became a place of Manchu Shamanist ceremony. At the same time, the native Chinese Taoist religion continued to have an important role throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties. There were two Taoist shrines, one in the imperial garden and another in the central area of the Inner Court.[63]

Another prevalent form of religion in the Qing dynasty palace was Buddhism. A number of temples and shrines were scattered throughout the Inner Court, including that of Tibetan Buddhism or Lamaism. Buddhist iconography also proliferated in the interior decorations of many buildings.[64] Of these, the Pavilion of the Rain of Flowers is one of the most important. It housed a large number of Buddhist statues, icons, and mandalas, placed in ritualistic arrangements.[65]

Surroundings

The Forbidden City is surrounded on three sides by imperial gardens. To the north is Jingshan Park, also known as Prospect Hill, an artificial hill created from the soil excavated to build the moat and from nearby lakes.[66]

To the west lies Zhongnanhai, a former royal garden centred on two connected lakes, which now serves as the central headquarters for the Communist Party of China and the State Council of the People's Republic of China. To the north-west lies Beihai Park, also centred on a lake connected to the southern two, and a popular royal park.

To the south of the Forbidden City were two important shrines – the Imperial Shrine of Family or the Imperial Ancestral Temple (Chinese: 太庙; pinyin: Tàimiào) and the Imperial Shrine of State (Chinese: 太社稷; pinyin: Tàishèjì), where the Emperor would venerate the spirits of his ancestors and the spirit of the nation, respectively. Today, these are the Beijing Labouring People's Cultural Hall[67] and Zhongshan Park (commemorating Sun Yat-sen) respectively.[68]

To the south, two nearly identical gatehouses stand along the main axis. They are the Upright Gate (Chinese: 端门; pinyin: Duānmén) and the more famous Tiananmen Gate, which is decorated with a portrait of Mao Zedong in the centre and two placards to the left and right: "Long Live the People's Republic of China" and "Long live the Great Unity of the World's Peoples". The Tiananmen Gate connects the Forbidden City precinct with the modern, symbolic centre of the Chinese state, Tiananmen Square.

While development is now tightly controlled in the vicinity of the Forbidden City, throughout the past century uncontrolled and sometimes politically motivated demolition and reconstruction has changed the character of the areas surrounding the Forbidden City. Since 2000, the Beijing municipal government has worked to evict governmental and military institutions occupying some historical buildings, and has established a park around the remaining parts of the Imperial City wall. In 2004, an ordinance relating to building height and planning restriction was renewed to establish the Imperial City area and the northern city area as a buffer zone for the Forbidden City.[69] In 2005, the Imperial City and Beihai (as an extension item to the Summer Palace) were included in the shortlist for the next World Heritage Site in Beijing.[70]

Symbolism

The design of the Forbidden City, from its overall layout to the smallest detail, was meticulously planned to reflect philosophical and religious principles, and above all to symbolise the majesty of Imperial power. Some noted examples of symbolic designs include:

- Yellow is the color of the Emperor. Thus almost all roofs in the Forbidden City bear yellow glazed tiles. There are only two exceptions. The library at the Pavilion of Literary Profundity (文渊阁) had black tiles because black was associated with water, and thus fire-prevention. Similarly, the Crown Prince's residences have green tiles because green was associated with wood, and thus growth.[46]

- The main halls of the Outer and Inner courts are all arranged in groups of three – the shape of the Qian triagram, representing Heaven. The residences of the Inner Court on the other hand are arranged in groups of six – the shape of the Kun triagram, representing the Earth.[15]

- The sloping ridges of building roofs are decorated with a line of statuettes led by a man riding a phoenix and followed by an imperial dragon. The number of statuettes represents the status of the building – a minor building might have 3 or 5. The Hall of Supreme Harmony has 10, the only building in the country to be permitted this in Imperial times. As a result, its 10th statuette, called a "Hangshi", or "ranked tenth" (Chinese: 行十; pinyin: Hángshí),[58] is also unique in the Forbidden City.[71]

- The layout of buildings follows ancient customs laid down in the Classic of Rites. Thus, ancestral temples are in front of the palace. Storage areas are placed in the front part of the palace complex, and residences in the back.[72]

Collections

The collections of the Palace Museum are based on the Qing imperial collection. According to the results of a 1925 audit, some 1.17 million pieces of art were stored in the Forbidden City.[73] In addition, the imperial libraries housed a large collection of rare books and historical documents, including government documents of the Ming and Qing dynasties.[74]

From 1933, the threat of Japanese invasion forced the evacuation of the most important parts of the Museum's collection. After the end of World War II, this collection was returned to Nanjing. However, with the Communists' victory imminent in the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist government decided to ship the pick of this collection to Taiwan. Of the 13,491 boxes of evacuated artifacts, 2,972 boxes are now housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. More than 8,000 boxes were returned to Beijing, but 2,221 boxes remain today in storage under the charge of the Nanjing Museum.[24]

After 1949, the Museum conducted a new audit as well as a thorough search of the Forbidden City, uncovering a number of important items. In addition, the government moved items from other museums around the country to replenish the Palace Museum's collection. It also purchased and received donations from the public.[75]

Today, there are over a million rare and valuable works of art in the permanent collection of the Palace Museum,[76] including paintings, ceramics, seals, steles, sculptures, inscribed wares, bronze wares, enamel objects, etc. According to an inventory of the Museum's collection conducted between 2004 and 2010, the Palace Museum holds a total of 1,807,558 artifacts and includes 1,684,490 items designated as nationally protected "valuable cultural relics."[77]

- Ceramics

The Palace Museum holds 340,000 pieces of ceramics and porcelain. These include imperial collections from the Tang dynasty and the Song dynasty, as well as pieces commissioned by the Palace, and, sometimes, by the Emperor personally. The Palace Museum holds about 320,000 pieces of porcelain from the imperial collection. The rest are almost all held in the National Palace Museum in Taipei and the Nanjing Museum.[78]

- Painting

The Palace Museum holds close to 50,000 paintings. Of these, more than 400 date from before the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). This is the largest such collection in China.[79] The collection is based on the palace collection in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The personal interest of Emperors such as Qianlong meant that the palace held one of the most important collections of paintings in Chinese history. However, a significant portion of this collection was lost over the years. After his abdication, Puyi transferred paintings out of the palace, and many of these were subsequently lost or destroyed. In 1948, many of the works were moved to Taiwan. The collection has subsequently been replenished, through donations, purchases, and transfers from other museums.

- Bronzeware

The Palace Museum's bronze collection dates from the early Shang dynasty. Of the almost 10,000 pieces held, about 1,600 are inscribed items from the pre-Qin period (to 221 BC). A significant part of the collection is ceremonial bronzeware from the imperial court.[80]

- Timepieces

The Palace Museum has one of the largest collections of mechanical timepieces of the 18th and 19th centuries in the world, with more than 1,000 pieces. The collection contains both Chinese- and foreign-made pieces. Chinese pieces came from the palace's own workshops, Guangzhou (Canton) and Suzhou (Suchow). Foreign pieces came from countries including Britain, France, Switzerland, the United States and Japan. Of these, the largest portion come from Britain.[81]

- Jade

Jade has a unique place in Chinese culture.[82] The Museum's collection, mostly derived from the imperial collection, includes some 30,000 pieces. The pre-Yuan dynasty part of the collection includes several pieces famed throughout history, as well as artifacts from more recent archaeological discoveries. The earliest pieces date from the Neolithic period. Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty pieces, on the other hand, include both items for palace use, as well as tribute items from around the Empire and beyond.[83]

- Palace artifacts

In addition to works of art, a large proportion of the Museum's collection consists of the artefacts of the imperial court. This includes items used by the imperial family and the palace in daily life, as well as various ceremonial and bureaucratic items important to government administration. This comprehensive collection preserves the daily life and ceremonial protocols of the imperial era.[84]

Influence

The Forbidden City, the culmination of the two-thousand-year development of classical Chinese and East Asian architecture, has been influential in the subsequent development of Chinese architecture, as well as providing inspiration for many artistic works. Some specific examples include:

- Depiction in art, film, literature and popular culture

The Forbidden City has served as the scene to many works of fiction. In recent years, it has been depicted in films and television series. Some notable examples include:

- The Forbidden City (1918), a fiction film about a Chinese emperor and an American.

- The Last Emperor (1987), a biographical film about Puyi, was the first feature film ever authorised by the government of the People's Republic of China to be filmed in the Forbidden City.

- Marco Polo a joint NBC and RAI TV miniseries broadcast in the early 1980s, was filmed inside the Forbidden City. Note, however, that the present Forbidden City did not exist in the Yuan dynasty, when Marco Polo met Kublai Khan.

- Live Performance concert venue

The Forbidden City has also served as a performance venue. However, its use for this purpose is strictly limited, due to the heavy impact of equipment and performance on the ancient structures. Almost all performances said to be "in the Forbidden City" are held outside the palace walls.

- Giacomo Puccini's opera, Turandot, the story of a Chinese princess, was performed at the Imperial Shrine just outside the Forbidden City for the first time in 1998.[85]

- In 1997, Greek-born composer and keyboardist Yanni performed a live concert in front of the Forbidden City. The concert was recorded and later released as part of the Tribute album.[86]

- In 2001, the Three Tenors, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti sang in front of Forbidden City main gate as one of their performances.

- In 2004, the French musician Jean Michel Jarre performed a live concert in front of the Forbidden City, accompanied by 260 musicians, as part of the "Year of France in China" festivities.[87]

See also

- Chinese art

- Chinese Palaces

- History of China

- History of Beijing

- Beijing city fortifications

- Imperial City, Beijing

- Beihai Park

- Zhongnanhai

- Jingshan Park

- Imperial Ancestral Temple

- Zhongshan Park

- Ming Palace, Nanjing

- National Palace Museum, Taipei

References

- ↑ "故宫到底有多少间房 (How many rooms in the Forbidden City)" (in Chinese). Singtao Net. 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- 1 2 Lu, Yongxiang (2014). A History of Chinese Science and Technology, Volume 3. New York: Springer. ISBN 3662441632.

- 1 2 "Advisory Body Evaluation (1987)" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- 1 2 "UNESCO World Heritage List: Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang". UNESCO. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Forbidden City to Regulate Visitor Numbers - CNTO China Like Never Before". CNTO China Like Never Before. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ p26, Barmé, Geremie R (2008). The Forbidden City. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ See, e.g., Gan, Guo-hui (April 1990). "Perspective of urban land use in Beijing". GeoJournal. 20 (4): 359–364. doi:10.1007/bf00174975.

- 1 2 p. 18, Yu, Zhuoyun (1984). Palaces of the Forbidden City. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-53721-7.

- ↑ "Gùgōng" in a generic sense also refers to all former palaces, another prominent example being the former Imperial Palaces (Mukden Palace) in Shenyang; see Gugong (disambiguation).

- 1 2 3 p. 15, Yang, Xiagui (2003). The Invisible Palace. Li, Shaobai (photography); Chen, Huang (translation). Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 7-119-03432-4.

- ↑ China Central Television, The Palace Museum (2005). Gugong: "I. Building the Forbidden City" (Documentary). China: CCTV.

- ↑ p. 69, Yang (2003)

- ↑ p. 3734, Wu, Han (1980). 朝鲜李朝实录中的中国史料 (Chinese historical material in the Annals of the Joseon Yi dynasty). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. CN / D829.312.

- ↑ Guo, Muoruo (1944-03-20). "甲申三百年祭 (Commemorating 300th anniversary of the Jia-Sheng Year)". New China Daily (in Chinese).

- 1 2 3 4 5 China Central Television, The Palace Museum (2005). Gugong: "II. Ridgeline of a Prosperous Age" (Documentary). China: CCTV.

- ↑ "故宫外朝宫殿为何无满文? (Why is there no Manchu on the halls of the Outer Court?)". People Net (in Chinese). 16 June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ Zhou Suqin. "坤宁宫 (Palace of Earthly Tranquility)" (in Chinese). The Palace Museum. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- 1 2 China Central Television, The Palace Museum (2005). Gugong: "XI. Flight of the National Treasures" (Documentary). China: CCTV.

- ↑ p. 137, Yang (2003)

- ↑ Yan, Chongnian (2004). "国民—战犯—公民 (National – War criminal – Citizen)". 正说清朝十二帝 (True Stories of the Twelve Qing Emperors) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 7-101-04445-X.

- ↑ Cao Kun (2005-10-06). "故宫X档案: 开院门票 掏五毛钱可劲逛 (Forbidden City X-Files: Opening admission 50 cents)". Beijing Legal Evening (in Chinese). People Net. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ See map of the evacuation routes at: "National Palace Museum – Tradition & Continuity". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ "National Palace Museum – Tradition & Continuity". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- 1 2 "三大院长南京说文物 (Three museum directors talk artefacts in Nanjing)". Jiangnan Times (in Chinese). People Net. 2003-10-19. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Chen, Jie (2006-02-04). "故宫曾有多种可怕改造方案 (Several horrifying reconstruction proposals had been made for the Forbidden City)". Yangcheng Evening News (in Chinese). Eastday. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Xie, Yinming; Qu, Wanlin (2006-11-07). ""文化大革命"中谁保护了故宫 (Who protected the Forbidden City in the Cultural Revolution?)". CPC Documents (in Chinese). People Net. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ The Forbidden City was listed as the "Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties" (Official Document). In 2004, Mukden Palace in Shenyang was added as an extension item to the property, which then became known as "Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang": "UNESCO World Heritage List: Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang". Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ Palace Museum. "Forbidden City restoration project website". Archived from the original on 21 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ↑ "闾丘露薇:星巴克怎么进的故宫?(Luqiu Luwei: How did Starbucks get into the Forbidden City)" (in Chinese). People Net. 2007-01-16. Retrieved 2007-07-25.; see also the original blog post here (in Chinese).

- ↑ Mellissa Allison (2007-07-13). "Starbucks closes Forbidden City store". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ Reuters (11 December 2000). "Starbucks brews storm in China's Forbidden City". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ "Two stores inside Forbidden City refuse entry to Chinese nationals" (in Chinese). Xinhua Net. 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ "Amazing Facts About the Forbidden City". Oakland Museum of California. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012.

- ↑ As larger buildings in traditional Chinese architecture are easily and regularly sub-divided into different configurations, the number of rooms in the Forbidden City is traditionally counted in terms of "bays" of rooms, with each bay being the space defined by four structural pillars.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (2001-08-31). "ART REVIEW; They Had Expensive Tastes". The New York Times.

- ↑ China Daily (2007-07-20). "Numbers Inside the Forbidden City". China.org.cn.

- ↑ "北京确立城市发展脉络 重塑7.8公里中轴线 (Beijing to establish civic development network; Recreating 7.8 km central axis)" (in Chinese). People Net. 2006-05-30. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Pan, Feng (2005-03-02). "探秘北京中轴线 (Exploring the mystery of Beijing's Central Axis)". Science Times (in Chinese). Chinese Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ↑ p. 25, Yang (2003)

- 1 2 p. 32, Yu (1984)

- ↑ Technically, Tiananmen Gate is not part of the Forbidden City; it is a gate of the Imperial City.

- 1 2 3 p. 25, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 33, Yu (1984)

- 1 2 p. 49, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 48, Yu (1984)

- 1 2 The Palace Museum. "Yin, Yang and the Five Elements in the Forbidden City" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ p. 253, Yu (1984)

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "太和殿 (Hall of Supreme Harmony)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "中和殿 (Hall of Central Harmony)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 30 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "保和殿 (Hall of Preserving Harmony)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ p. 70, Yu (1984)

- ↑ For an explanation and illustration of the joint, see p. 213, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 73, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 75, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 78, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 51, Yang (2003)

- ↑ pp. 80–83, Yu (1984)

- 1 2 China Central Television, The Palace Museum (2005). Gugong: "III. Rites under Heaven " (Documentary). China: CCTV.

- ↑ p. 121, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 87, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 115, Yu (1984)

- ↑ Powell, Eric. "Restoring an Intimate Splendor" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

- ↑ p. 176, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 177, Yu (1984)

- ↑ pp. 189–193, Yu (1984)

- ↑ p. 20, Yu (1984)

- ↑ "Working People's Cultural Palace". China.org.cn. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ↑ "Zhongshan Park". China.org.cn. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ↑ "Forbidden City Buffer Zone Plan submitted to World Heritage conference" (in Chinese). Xinhua Net. 2005-07-16. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ Li, Yang (2005-06-04). "Beijing confirms 7 World Heritage alternate items; Large scale reconstruction of Imperial City halted" (in Chinese). Xinhua Net. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Hall of Supreme Harmony" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (Dec 1986). "Why were Chang'an and Beijing so different?". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 45 (4): 339–357. doi:10.2307/990206. JSTOR 990206.

- ↑ Wen, Lianxi (ed.) (1925). 故宫物品点查报告 [Palace items auditing report]. Beijing: Caretaker Committee of the Qing dynasty Imperial Family. Reprint (2004): Xianzhuang Book Company. ISBN 7-80106-238-8.

- ↑ Dorn, Frank (1970). The forbidden city: the biography of a palace. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 176. OCLC 101030.

- ↑ "北京故宫与台北故宫 谁的文物藏品多? (Beijing Palace Museum and Taipei Palace Museum: which collection is bigger?)". Guangming Daily (in Chinese). Xinhua Net. 2005-01-16. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Jackie Craven. "Forbidden City in Beijing, China". About.com: Architecture.

- ↑ "Palace Museum puts its house in order". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Ceramics" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Paintings" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Bronzeware" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Timepieces" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Laufer, Berthold (1912). Jade: A Study in Chinese Archeology & Religion. Gloucestor MA: Reprint (1989): Peter Smith Pub Inc. ISBN 978-0-8446-5214-6.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Jade" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Palace artifacts" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ "Turandot at the Forbidden City, Beijing 1998". Retrieved 2007-05-01.; note some inconsistency in the description of the venue on the official site: it claims that the venue, the People's Cultural Palace, was the "Hall of Heavenly Purity". In fact, the Working People's Cultural Palace was the Temple to the Emperor's Ancestors= China.org: Working People's Cultural Palace.

- ↑ "Biography". Archived from the original on 14 August 2011.

- ↑ "Jean Michel Jarre lights up China". BBC. 2004-10-11. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

Further reading

- Aisin-Gioro, Puyi (1964). From Emperor to citizen : the autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 0-19-282099-0.

- Huang, Ray (1981). 1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02518-1.

- Yang, Xiagui (2003). The Invisible Palace. Li, Shaobai (photography); Chen, Huang (translation). Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 7-119-03432-4.

- Yu, Zhuoyun (1984). Palaces of the Forbidden City. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-53721-7.

- Barmé, Geremie R (2008). The Forbidden City. Harvard University Press. 251 pages. ISBN 978-0-67402-779-4.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2007). The Imperial Capitals of China – An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. London: Pimlico. 304 pages. ISBN 978-1-84595-009-5.

- Ho; Bronson (2004). Splendors of China's Forbidden City. London: Merrell Publishers. ISBN 1-85894-258-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palace Museum. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Forbidden City. |

- Palace Museum official site (Digital Palace Museum)

- National Palace Museum (Taipei) official site

- Forbidden City, a photographic tour

- Satellite photograph of the Forbidden City

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre – panographies (360 degree imaging)

-

Geographic data related to Forbidden City at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Forbidden City at OpenStreetMap