Johann Mickl

| Generalleutnant Johann Mickl | |

|---|---|

Johann Mickl wearing the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves | |

| Born |

18 April 1893 Radkersburg, Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Died |

10 April 1945 (aged 51) Rijeka, Yugoslavia |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Generalleutnant |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves Order of the Iron Crown 3rd Class (Austria-Hungary) Military Merit Cross 3rd Class (Austria-Hungary) Military Merit Medal for Bravery in Silver and bar (Austria-Hungary) |

Johann Mickl (18 April 1893 – 10 April 1945) was an Austrian-born Generalleutnant and division commander in the German Army during World War II, and was one of only 882 recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves. He was commissioned shortly before the outbreak of World War I, and served with Austro-Hungarian forces on the Eastern and Italian Fronts as company commander in the Imperial-Royal Mountain Troops. During World War I he was decorated several times for bravery and leadership, and was wounded on several occasions, finishing the war as an Oberleutnant.

Immediately after the war, Mikl served in the Volkswehr militia which was formed to resist the incorporation of his home town of Radkersburg into the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. He served with the Austrian Army from 1920 until the Anchluss in 1938, when it was absorbed by the Wehrmacht, and he transferred to the German Army as an Oberstleutnant. He commanded an anti-tank battalion during the invasion of Poland and Battle of France, during which he was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd and 1st Class, and was promoted to Oberst. Through the intervention of a friend, the adjutant of Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel, under whose command he had served in France, Mickl was transferred to North Africa to command a rifle regiment. He was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross for his leadership of a kampfgruppe during the Battle of Sidi Rezegh, during which he and 800 of his soldiers were captured by New Zealand troops. Two days later he precipitated a successful mass escape from a prisoner of war collection point.

He briefly commanded the 90th Light Division Afrika in late 1941 before being wounded. After he recovered he was sent to the Eastern Front. Mickl commanded the 12th Rifle Brigade of the 12th Panzer Division in the east, taking over the 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment when his brigade headquarters was disestablished. Transferred to the Führerreserve, he was promoted to Generalmajor, and received the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross for his outstanding commitment and leadership during the Soviet 1942–43 winter offensives around Rzhev. He then commanded the 11th Panzer Division during the Battle of Kursk. Later in 1943, he was appointed to train and command the 392nd (Croatian) Infantry Division, and led it in fighting against the Yugoslav Partisans before dying of wounds inflicted in the last month of the war. In 1967, the Austrian Bundesheer barracks in Bad Radkersburg were named after him.

Early life and career

Mickl was born Johann Mikl in Zelting, Radkersburg, which was part of the Duchy of Styria within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father Mathias was a German farmer from Terbegofzen, and his mother Maria (née Dervarič), was from Zelting, and of at least partially Slovene heritage.[1][2] Mikl had a twin brother, Alois, who was killed in action in 1915 in Galicia near Lemberg, present-day Lviv in the Ukraine.[3] As a child, Mikl spoke German, Slovene and Hungarian, and remained fluent in all three throughout his life.[2]

After entering a cadet school in Vienna in the Imperial-Royal Landwehr in 1908,[2] he was accepted at the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt in 1911. Described as slim, muscular, and 1.92 metres (6 ft 4 in) tall,[4] Leutnant Mikl graduated on 1 August 1914 and was posted to the recently mobilised 4th Imperial-Royal Landwehr Infantry Regiment (LIR 4), which formed part of the Imperial-Royal Mountain Troops.[5]

World War I

Galicia

LIR 4 was a purely Carinthian regiment, and wore the mountain cap (German: Bergmütze) and the Edelweiss badge. As part of the 22nd Rifle Division of the III Corps, Mikl's regiment entrained for the Eastern Front, were offloaded in Stryj in Galicia and marched into the area of Złoczów to take up a position on the Złota Lipa River. Its baptism of fire was an attack on the Russians on 26 August 1914, during which it received inadequate artillery support and suffered heavy casualties.[6] One of those wounded was Mikl, who was shot in the chest. He spent time in a military hospital and was then employed in the regimental replacement battalion as an instructor until 15 April 1915. Nothing is known about Mikl's activities during that period, although LIR 4 was involved in heavy fighting in Galicia throughout the winter, in temperatures that dropped below −20 °C (−4 °F).[7]

On 1 June 1915, LIR 4 received orders to be transferred to the Southern Front, as Italy had entered the war against the Central Powers the previous month.[8] This order was countermanded the following morning when the Russians launched an offensive in the Kolomea region and the Austrians suffered serious reverses. LIR 4 was immediately committed to the battle.[8] The army commander, General der Kavallerie (lieutenant general) Karl von Pflanzer-Baltin later stated that it was the courage of LIR 4 that had stopped the Russians. Mikl had led from the front during the fighting, especially when his company formed the regimental rear guard during the withdrawal from the Pruth river on 3 June. At one point, Mikl used parts of a damaged train to build a defensive position. He was wounded several times during the fighting, but remained with his soldiers. For his actions and "demonstrated personal bravery", Mikl was awarded the Military Merit Cross 3rd Class with War Decoration (German: Militärverdienstkreuz III. Klasse und Kriegsdekoration).[8]

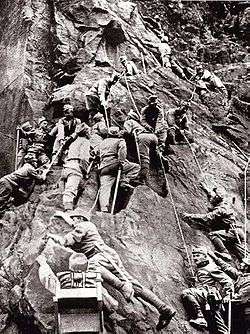

Italian front

By late September 1915, LIR 4 had been transferred to the Flitsch valley in the Julian Alps on the Southern Front, and Mikl had been promoted to Oberleutnant (first lieutenant) and placed in command of the 2nd Company.[9] A fairly quiet winter followed, during which the Austrians undertook reconnaissance of Italian positions, took prisoners, and captured weapons. In August 1915, Italian Alpini troops had captured an advanced position about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) southwest of the 2,208 metres (7,244 ft) Rombongipfels peak, on a rocky outcrop called Cuklahöhe. From this position the Italians overlooked the positions of the 44th Rifle Division and its rear areas, which made movement almost impossible. The group commander, Oberst (colonel) Artur von Schuschnigg tasked Mikl and his company to capture the Cuklahöhe, and allowed him to determine the best way to complete his mission. Between 30 January and 8 February 1916, Mikl and Fähnrich (cadet sergeant) Schlatte reconnoitred the Italian position each night. It dominated the ground around it, and was protected by barbed wire entanglements.[10] On 8 February, they located a narrow channel that they considered could be used to approach the Cuklahöhe without exposing the assault force to Italian fire. Mickl's plan involved a silent attack by his company using the channel, foregoing artillery preparation, as this would warn the Italians of the impending assault.[11]

After a few days delay caused by heavy snowfalls, the attack commenced at 02:45 on 12 February.[11] During the approach march to the foot of the Cuklahöhe, some men disappeared up to their neck in snow due to the many snow-filled depressions and the depth of the snow. This meant that the march to the bottom of the channel took two hours instead of the thirty minutes Mikl had estimated. When they reached the bottom of the channel, they had to climb a 3 m (9.8 ft) high smooth ice wall to enter the gutter, which even highly experienced climbers were unable to scale. Around 06:00, the whole company had assembled at the bottom of the channel, but dawn was beginning to break, threatening to expose the assembled force to flanking Italian positions. Schlatte then came forward, carrying the trunk of an alpenrose, a shrub that grows just above the tree-line in the Alps. He used the trunk to reach the channel ledge, and the troops were able to enter the gutter with his help. The troops could now see the glow of the candles in the Italian position. The assault took the Italians completely by surprise, and three officers and 84 soldiers surrendered, for the loss of four dead, including one officer, and four wounded.[12] The Italian response was to concentrate all available artillery fire on the position. The dugout was exposed to direct Italian fire, and was therefore unusable. The Austrians were in an exposed position in deep snow and with extremely cold winds at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,600 ft), and during the first day Mikl's company lost 20 dead and 60 seriously wounded. On the night of 15 February, the Italians commenced two days of unsuccessful counterattacks, some carried out in four or five consecutive waves. For several weeks starting on 17 February, Benito Mussolini, then a member of the Italian 11th Bersaglieri Regiment, was on the front line near the Cuklahöhe, and described some of his experiences in his diary.[13] On 5 March, prior to the withdrawal of his company from the Cuklahöhe, Mikl was wounded in the face by an Italian hand grenade. When his company was relieved on the Cuklahöhe on 12 April, it had shrunk to just 44 men. For his leadership of the assault on the Cuklahöhe, Mikl was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown 3rd Class.[14] On 10 May, the Cuklahöhe was retaken by the Italians from three companies of Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry, who lost 250 men. The assault force, consisting of four battalions of the Italian 24th Infantry Division lost 18 officers and 516 men.[15]

In April 1916, Mikl's regiment was deployed to South Tyrol to take part in the Austrian spring offensive, during which he was awarded the bronze Military Merit Medal on the ribbon of the Bravery Medal with War Decoration (German: Militär Verdienstmedaille am Bande der Tapferkeitsmedaille mit Kriegsdekoration), for leading a successful attack on an Italian position on Monte Cengio. At the end of June, his regiment was transported back to Galicia by rail to reinforce the Austro-Hungarian forces being hard-pressed by the Russian Brusilov Offensive. In July, Mikl's regiment was used as a "fire brigade" within the Army Group, and helped prevent the penetration of the Russian offensive through the Jablonika Pass. Their task completed, Mikl's regiment was promptly transferred back to fight the Italians on the Southern Front. Mikl's regiment arrived on the Isonzo Front on 20 August, and remained there until late autumn 1917, fighting in the 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th Battles of the Isonzo. During the Eighth Battle of the Isonzo on 10 October 1916, Mikl was wounded once again, and was hospitalised. When he recovered, he was assigned to the regimental replacement battalion until spring 1917. For three months during the summer of 1917, Mikl was employed as an instructor at the VII Corps Reserve Officer's School, preparing young officers for service at the front.[16] In January 1917, he was awarded the silver Military Merit Medal on the ribbon of the Bravery Medal with War Decoration.[17] In August 1917, Mikl was appointed to command a machine gun company, and served in the Battle of Caporetto and the subsequent advance to the Piave river.[18] On 12 November 1917, Mikl's regiment was the first to establish a bridgehead over the Piave at Zenson di Piave, and he was instrumental in rallying the troops of his regiment when they came under heavy fire as they landed on the Italian side of river. For his leadership at this crucial stage of the river crossing, he was awarded a bar to his silver Military Merit Medal.[19] On 15 May 1918,[20] Mikl began a preparatory course for future attendance at the War College (German: Kriegsschule) in Vienna, and when the war ended he was posted to the 54th Rifle Division in Galicia.[18][20]

Between the wars

Before the war, nationalism had been largely absent in officers of the Austro-Hungarian Army, but this changed during the war, and by the end of the war, the propaganda of the Entente had combined with wider aspirations to encourage nationalist sentiment. In some cases, this resulted in mutiny among units of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the last months of the war. The states that would succeed Austria-Hungary were approved by the Allies on 28 October 1918,[21] and the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was dissolved three days later. Many new nation states emerged in the territory formerly belonging to the realm, as nationalist movements called for greater autonomy or full independence. The Duchy of Styria was divided between the new states of German-Austria and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but the exact line of the new border was unclear.[22] In November 1918, Mikl had returned to his hometown of Radkersburg,[20] an important railway junction point, which was of economic importance to both sides.[23] The Slovenes occupied the city on 1 December 1918.[22] In 1919, Mikl served as adjutant in the 1st Battalion of the Volkswehr militia,[24][18] which used arms provided by the provincial government of Carinthia to make an unsuccessful attempt to recapture Radkersburg from forces of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to ensure it remained part of German-Austria.[5][25] The provincial government of Styria, which had not supported these actions, subsequently issued a warrant ordering Mikl's arrest for treason. Despite his failure, his actions were very important in demonstrating to those negotiating the final border that towns along the northern bank of the Mura river were German. When the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed later in 1919, Radkersburg was retained within what became the First Austrian Republic.[5]

In 1920, Mikl was accepted by the new Austrian Army (German: Bundesheer), joining the 11th Alpenjäger Regiment.[24] During 1920–21 he was rapidly promoted to Hauptmann (captain),[26] and on 20 October 1920 he was posted to the 5th Cyclist Battalion in Villach, Carinthia. In 1921, his battalion was deployed to Burgenland to assist in the transfer of that region from Hungary to Austria.[24] In 1922,[27] he changed his name to the more Germanised Mickl.[2] According to his biographers Richter and Kobe, at this time the Austrian police wanted to speak to Mikl regarding alleged arms trafficking offences, and his decision to change his name may have related to the police inquiries.[28] On 2 May 1922, Mickl married Helene Zischka in Klagenfurt; their only child, Manfred, was born in 1923.[5] That same year, he was promoted to the rank of Major,[24] having worked on the frontier with Italy, trained border guards and proving an accomplished mountaineer.[28]

In 1925, Mickl passed the examinations for the general staff.[24] On 26 July 1930,[17] Mickl was appointed an honorary citizen (German: Ehrenbürger) of the town of Radkersburg.[5] During fifteen years with the 5th Cyclist Battalion, Mickl had attended ski courses and mountain leadership courses, and had also developed an interest in automotive technology. In 1934, he briefly served on the military headquarters for Carinthia in Klagenfurt.[24] In February of the following year, he was placed on the general staff officer list,[24][5] and posted to the headquarters of the 3rd Brigade at St. Pölten.[26] His promotion to Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) followed in 1936.[27] In the same year, Mickl's son Manfred entered the military cadet school at Enns.[28] On 14 March 1938,[28] following the Anschluss, Mickl was absorbed at his rank into the German Army,[5] but as a troop officer, not a general staff officer.[28] From 12 May to mid-August 1938,[29] he attended training at the Panzertruppenschule II (Armoured Troops School No. 2) in Wünsdorf south of Berlin,[30] before being given command of the 42nd Panzerjäger (Anti-tank) Battalion of the 2nd Light Division.[27][29] Helene soon moved to Gera in Thuringia to join Mickl, leaving the 15-year-old Manfred at the cadet school until his graduation.[29]

World War II

Poland and France

Mickl commanded the 42nd Panzerjäger Battalion of Generalmajor (brigadier) Georg Stumme's 2nd Light Division during the September 1939 invasion of Poland,[27] during which the division was involved in difficult fighting through Kielce and Radom in central Poland to Modlin on the Vistula. The following month,[29] Mickl was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class.[31] During the winter of 1939/40, the 2nd Light Division was reclassified and converted into the 7th Panzer Division, in preparation for the invasion of France and the Low Countries. In February 1940, Generalmajor Erwin Rommel arrived to take command of the division.[29]

Mickl remained in charge of the 42nd Panzerjäger Battalion during the invasion. He got along well with Rommel, and his battalion fought well but suffered serious casualties during the Battle of Arras on 21 May while trying to stop the heavily armoured tanks of the British 1st Army Tank Brigade with its 37 mm anti-tank guns.[30] His soldiers derided their guns as Panzeranklopfgerät (tank-door knocker), due to their failure to penetrate the British Matilda I and Matilda II tanks. Mickl's battalion tried to protect the exposed flank of the division, but was overrun. The situation was saved by anti-aircraft guns and field artillery which were able to knock out the British tanks with direct fire.[32]

Rommel received reports of Mickl's personal courage during the battle, and recognised aspects of his subordinate's leadership style that mirrored his own. On 1 June, he promoted Mickl to Oberst and on 21 June awarded him the Iron Cross 1st Class.[32][30] After the French surrender, Mickl was attached to the division's 25th Panzer Regiment to gain more knowledge about armoured tactics, and on 10 December 1940 was appointed to command the 7th Rifle Regiment of the division.[30] Rommel did not remain with the division long, being transferred to command the Afrika Corps. He was replaced by Generalmajor Hans Freiherr von Funck, with whom Mickl had some difficulty working.[33] Mickl remained in command of the 7th Rifle Regiment during occupation duties in southwestern France, redeployment to Germany, and during the division's preparation for the invasion of the Soviet Union.[30] In May 1941, through the intervention of Rommel's adjutant Major Hans-Joachim Schraepler, Mickl was posted to a new role in Germany, raising the headquarters of the 155th Rifle Regiment for service in North Africa. Despite the difference in age and rank, Mickl, Schraepler and their wives had become firm friends. The 155th Rifle Regiment was to be a motorised formation of three battalions, one drawn from each of the 106th, 112th and 113th Infantry Divisions.[33]

North Africa

In August 1941, Panzergruppe Afrika was raised, and the newly promoted General der Panzertruppe Rommel was placed in command. The Afrikakorps was handed over to Generalleutnant Ludwig Crüwell. Soon after, Mickl followed the battalions of his regiment to North Africa, arriving there in early September 1941. He found them to be under-equipped, having been furnished with only a few vehicles and only two 37 mm anti-tank guns per battalion. He considered that this would be sufficient for an attack on defensive positions, but completely inadequate for mobile operations. On 6 September, his regiment joined the Siege of Tobruk taking up positions at Ras el Mdauuar until the end of October, when it became part of the composite Afrika (Special Purpose) Division and prepared for an attack on the fortress. When a strong British reconnaissance force was reported far to the south, moving west from the Egyptian border at Sidi Omar, Mickl was placed in command of a kampfgruppe which was sent to meet the British. The force consisted of Mickl's regiment, along with the 361st Afrika Regiment and the 605th Panzerjäger Battalion. The Afrika Regiment had only just arrived in theatre, and had no heavy weapons, insufficient ammunition and almost no vehicles.[34]

By the following day, Mickl's kampfgruppe was deployed on the high ground on either side of the airfield at Sidi Rezegh. That afternoon, British armoured cars and tanks appeared, and Mickl's force was hard-pressed to hold its positions barring the British approach to Tobruk from the south and south-east, as little tank support was available.[35] In the face of a superior force, Mickl's kampfgruppe fought hard in what became known as the Battle of Sidi Rezegh, with their commander often forward rallying his troops, and in the thick of counter-attacks launched to regain ground. Mickl and around 800 of his troops were captured by elements of the New Zealand Division on 26 November 1941, the captured troops being mainly from the Afrika Regiment.[36]

After two days under guard at a temporary collection point, Mickl observed elements of the 15th Panzer Division travelling on the Trigh Capuzzo (Capuzzo Track), returning from their sortie against the rear of the British assault. The prisoners of war were surrounded by a largely "symbolic" barbed wire fence, and in addition to the small guard force, the makeshift camp was surrounded by scattered British headquarters and logistic units. Mickl approached the officer in charge, who was watching the progress of the German tanks through binoculars, and knocked him to the ground. Seeing this, the German soldiers subdued the guards and took off on foot towards the nearby German column. Taking the keys to a vehicle, Mickl drove towards the distant German tanks to warn them of his approaching men. Rommel's staff were soon apprised of Mickl's actions by Crüwell. The British soon lifted the siege, and Mickl's regiment acted as rearguard during the withdrawal of Axis forces to El Agheila, where on 11 December, his previously 2,000-strong regiment could only muster seven officers and 492 men. During the withdrawal, his ally and friend Schraepler was killed in a vehicle accident.[37]

When the commander of the newly renamed 90th Light Afrika Division, Generalmajor Max Sümmermann, was killed in an Allied air raid on 10 December 1941, Mickl was appointed to temporarily command the division. During December, Mickl was wounded in the head and hand, but remained at his post.[38] Rommel recommended Mickl for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross,[39] for his leadership at Sidi Rezegh, and it was duly awarded on 13 December 1941.[38] The harsh conditions of desert warfare had begun to affect Mickl's health, so at the end of December he was sent home on convalescent leave.[40]

Eastern Front

12th Rifle Brigade

On 25 March 1942,[41] Mickl was appointed to command the 12th Rifle Brigade of Generalmajor Walter Wessel's 12th Panzer Division on the Eastern Front. The division was the main reserve formation of Army Group North,[40] and when Mickl joined his brigade headquarters it was located on the coast near Narva west of Leningrad. The 12th Rifle Brigade consisted of the 5th and 25th Motorised Infantry Regiments. As a subordinate formation of General der Kavallerie Georg Lindemann's 18th Army, during the Red Army Winter Campaign of 1941–42 it had fought on the Volkhov Front, during which the Lyuban Offensive Operation had penetrated deep into its area of operations in an attempt to relieve Leningrad. When Mickl arrived to take command, elements of his command were fighting as part of a total of twenty 18th Army kampfgruppen engaged in encircling and destroying cut-off Soviet units. It was not until May that Mickl was able to start gather his brigade together.[41] At the end of June, Mickl was still collecting and re-organising his brigade when he received news that his son Manfred had been seriously wounded in the leg during the Axis capture of Tobruk. Manfred was a Leutnant in the Pioneers, and had already been decorated with the Iron Cross 1st Class.[42][lower-alpha 1]

By 17 July, the 12th Panzer Division was finally concentrating near Mga, 60 kilometres (37 mi) south-east of Leningrad, and Mickl's brigade was reclassified as a Panzergrenadier brigade. Mickl found this change mildly amusing, noting that his transport consisted mainly of peasant carts and train carriages. He nevertheless attacked the task of retraining his regiments and battalions with vigour, conducting a series of tank-infantry co-operation exercises. Between 25 August and 16 September, Mickl visited Manfred in hospital in Naples while on leave, but he returned to find that his brigade had again been parceled out in kampfgruppen used as "fire brigades" along the Neva River. Frustrated, he complained that he and his staff did not appear to have a purpose, as they were usually bypassed by the division commander and staff. It was not until 17 October that he was able to collect his scattered troops and arrange for them to be transported south to an area west of Nevel near the boundary with Army Group Centre. By this time, it had become apparent that Mickl's brigade headquarters was being not employed as originally intended, and along with the brigade staff of all Panzer divisions, it was disestablished.[44]

25th Panzergrenadier Regiment

Without a command, Mickl remained with the 12th Panzer Division, taking over the 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment, whose commander had fallen ill. In the new area, Mickl concentrated on training and getting to know his men, before conducting an anti-partisan operation named Affenkäfig (Monkey Cage) between 11 and 14 November 1942. Lacking experience in counter-insurgency, the regiment achieved little. Mickl then concentrated his troops' efforts on securing winter quarters and building shelters for the regiment's vehicles. On the frontlines, 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of Nevel, Soviet forces were threatening to break through around the Rzhev salient and encircle the German 9th Army, and on 21 November the 12th Panzer Division received orders to march for the front. The march east, undertaken in freezing conditions and heavy snow, was very difficult. The men lit small stoves in the rear of the trucks to keep warm, and often had to clear the snow-clogged roads with shovels.[45]

Initially they were ordered to Roslavl, south-east of Smolensk, but this was soon changed to Yelnya, east of Smolensk. When they reached Smolensk, they marched on through Yartsevo to Safonovo before being ordered to turn north towards Bely to help stop a Soviet breakthrough south of Rzhev. At the head of the division, the 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment attacked off the route of march towards elements of the 1st Panzer Division holding out around the village of Komary. The fighting continued in snowstorms and extreme cold until 16 December, with Mickl forward directing the battle, which ended with the destruction of eight Soviet tank and rifle brigades in the Bely area. After a few days rest, on 23 December Mickl's regiment marched to the north-east of Bely to stop Soviet forces moving into the Luchesa river valley. In the difficult terrain and weather conditions, the regiment was exhausted from constant fighting over hamlets that often changed hands.[46] On 30 December, the fighting escalated as the Red Army forces in the sector were reinforced, and Mickl's II Battalion was forced to temporarily withdraw into the surrounding forest. Fierce fighting continued until the 12th Panzer Division was detached at short notice on 14 January 1943, but not before the divisional staff had reported Mickl's brave leadership in the fighting to the Oberkommando des Heeres (German Army High Command). On 16 January 1943, the division was on the move, this time headed north-west to Velikiye Luki, but its move to the front was countermanded.[47]

Führerreserve

On 26 January 1943, Mickl received orders to report to Berlin on 2 February, although Wessel was reluctant to lose his outstanding regimental commander. In a formal assessment on 20 November 1942, Wessel had assessed Mickl as having the aptitude to command a Panzer division, and he supplemented this on 28 January, extolling his "almost unparalleled bravery and boldness" in command of the 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment. On 30 January, Mickl arrived in Gera on leave to visit his wife Helene, and spent the next three months in the Army Headquarters officers' reserve pool (German: Oberkommando des Heeres Führerreserve').[48]

On 1 March he was promoted to Generalmajor, and five days later he became the 205th recipient of the Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his outstanding commitment as the commander of the 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment during winter 1942–43. Of modest habits, Mickl had rarely worn the Knight's Cross itself, usually wearing only the ribbon around his neck, and now he merely added the Oak Leaves device to the ribbon. During his time in the Führerreserve, he also had the opportunity to meet with his mentor Rommel, now a Generalfeldmarschall, and he also attended a course for divisional commanders, which he referred to as a "fool's course". In early May, Mickl was summoned to Berlin and advised that he was to be entrusted with the command of the 11th Panzer Division during the absence of Generalleutnant Dietrich von Choltitz, who had been suffering with heart problems. Despite the good news of being appointed to a divisional command, Mickl expressed his disappointment that he was being allocated a division in need of re-organisation, rather than a fully equipped and full-strength modern division.[49]

11th Panzer Division

When Mickl took command, the 11th Panzer Division had not yet finished rebuilding after suffering serious losses during the attempted relief of Stalingrad in December 1942 and during the Third Battle of Kharkov in February and March 1943.[40] The 11th Panzer Division formed part of General der Panzertruppe Otto von Knobelsdorff's XLVIII Panzer Corps under the operation control of Generaloberst Hermann Hoth's 4th Panzer Army, which was itself a component of Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein's Army Group South.[50] Prior to the launching of Operation Citadel targeting the Soviet salient at Kursk, the XLVIII Panzer Corps was quartered southwest of a line between Bohodukhov and Akhtyrka.[51]

For the main assault, Army Group South was the southern pincer of a manoevre aimed at cutting off all Red Army forces within the Kursk salient. It was to attack north out of the areas west of Belgorod, and link up with Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge's Army Group Centre, which was to attack south from the Orel region.[52] On the afternoon of 4 July,[40] the 4th Panzer Army successfully conducted a preliminary operation to breach minefields and secure the heights overlooking the nearly 40 kilometres (25 mi) deep Soviet defensive positions near Kursk, which were essentially a series of staggered defensive positions and minefields reinforced with anti-tank weapons.[53]

Mickl's division achieved its objectives during the preliminary operation, and commenced its main assault at 06:00 on 5 July.[54] The 11th Panzer Division advanced on the right flank of the XLVIII Panzer Corps, and on the left of the powerful Panzergrenadier Division Großdeutschland.[55] Its progress was hampered by minimal air support, difficult terrain and constant Soviet counterattacks.[54] Fighting alongside a Panzerkampfgruppe of the Großdeutschland Division led by Oberst Theodor Graf Schimmelmann von Lindenburg, it had captured the heavily fortified village of Cherkasskoye. By the evening of 6 July, XLVIII Panzer Corps had breached the first belt of the formidable Soviet defences,[55] and Mickl's division had reached the Pena river north and northeast of Cherkasskoye.[54] This was 40 kilometres (25 mi) short of the objective Hoth had set for 6 July, the bridge over the Psel River at Oboyan.[55]

.jpg)

XLVIII Panzer Corps regrouped during the night of 6/7 July, and the 11th Panzer Division continued its advance towards Oboyan on 7 July, alongside the Großdeutschland Division. Over the next few days, the two divisions overcame resistance from a series of Soviet strongpoints, along with their desperate counterattacks. By 10 July they had reached a position east of the Kursk-Kharkov road, on the heights 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) south of Oboyan,[55] having defeated advanced elements of the Soviet 10th Tank Corps.[54] At this point the previously rough terrain opened up, and with the aid of binoculars the men of the division could see the vast plain behind Oboyan in which the two pincers of Operation Citadel were planned to meet. But the northern pincer had been stalled north of Kursk in heavy fighting,[55] and the 11th Panzer Division had gained the most northern penetration into the Soviet salient achieved by Army Group South during the operation.[54]

Twice in the next few days, XLVIII Panzer Corps attempted to punch through the Soviet defences to the north, while to the east the II SS Panzer Corps and German Army Detachment Kempf fought the tanks of the Soviet Steppe Front. The 11th Panzer Division was then ordered to attack towards the upper reaches of the Psel, some 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the east, followed by the Großdeutschland Division once it had captured Oboyan. The two divisions were then to link up with the II SS Panzer Corps and defeat the Soviet forces concentrated around Prokhorovka.[56] On 17 July, these orders were cancelled, and over the next week, Mickl's division fought defensive battles against the Red Army, and conflict arose with his subordinate commanders and his key staff, who did not support his style of leadership, which was modelled on that of his mentor Rommel. For nearly that whole week, Mickl's division bore the brunt of the Soviet attacks on the XLVIII Panzer Corps.[57]

On 21 July, Mickl wrote a letter in which he stated that he wished to again be a battalion or regimental commander, so as to not have to deal with such a large frontline. That day he had been told that the next day he should expect Choltitz to return and take over command, but instead he spent a further three weeks commanding the 11th Panzer Division in heavy fighting against Soviet attacks. Finally, on 12 August he received a message advising that he was to be relieved by Generalmajor Wend von Wietersheim, who arrived that same day. Four days later, Mickl returned to Gera, disappointed and resentful about the demotion, as he felt that he had made a good enough impression during the fighting to be retained as commander of the division.[57] The reason behind his relief is unclear. His performance commanding the division had not been markedly worse than comparable divisional commanders during the preceding battles, and it is possible that Wehrmacht or Army Headquarters had decided Mickl was better suited to fighting insurgents in his native Balkans, especially given his fluency in several local languages.[58]

Yugoslavia

.svg.png)

A new division

After three weeks leave, Mickl was sent to Austria to train and command the 392nd (Croatian) Infantry Division.[40] He was appointed to this command on 13 August 1943, and according to his biographers Richter and Kobe, he must have been aware of this eventuality when he was appointed to temporarily command the 11th Panzer Division earlier that year, although he never got over his disappointment at not being given permanent command of a Panzer division.[59] Commencing from 17 August, the 392nd was assembled and trained in Austria as the third and last Croatian division raised for service in the Wehrmacht, following its sister divisions the 369th and the 373rd. One infantry regiment and the divisional artillery regiment formed in Döllersheim, the other infantry regiment in Zwettl, the signals battalion in Stockerau and the pioneer battalion in Krems.[60] It was built around a cadre of 3,500 German officers, NCOs and specialists, and 8,500 soldiers of the Croatian Home Guard, the regular army of the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH).[61] The former Home Guard troops included a few young officers and NCOs,[59] but the division was commanded by Germans down to battalion and even company level in nearly all cases, and was commonly referred to as a "legionnaire division".[62] The division wore Wehrmacht uniform with the shield chequy argent et gules of the NDH on the upper right sleeve and right side of the steel helmet.[59] Although originally intended for use on the Eastern Front, not long after its formation the Germans decided that the division would not be utilised outside the NDH.[63] Richter and Kobe observed that, given his experience and fluency in Balkan languages, no-one would have been more suitable to command the division than Mickl.[59] Mickl had four months to whip the division into shape, and ensure that it was equipped, staffed and resourced to do the tasks that lay ahead. Soon the Croatian soldiers became familiar with the tall frame of their commander, whose Austro-Hungarian decorations were familiar to them, but who also wore the Oakleaves and spoke their language. During the training, Mickl once remarked to the assembled officers:[64]

"Gentlemen, I know that you have been discussing whether or not we can still win this war. All of you have fought on several fronts and some have come from the battlefields of Russia. It should therefore be clear to you that there will be no victory for us. But I will not tolerate such discussions. Most of us are career officers. When we joined, no-one guaranteed that we would win any war. We fight not only when victory is guaranteed, but we do our duty and fight where we are, even if that means our inevitable doom. To fight on without a chance of victory is not pointless, because it serves to avert as much damage as possible to Germany. Preventing the advance of Tito's communist-oriented partisans to the north is part of this struggle.

These comments were extremely dangerous, as Mickl did not know all his officers or their allegiances, and many officers and men had been court-martialled and shot for similar pronouncements that revealed the speaker did not believe in "ultimate victory". Mickl recognised the difficulties he faced, with "volunteers" who were really conscripts, and the Croats' allegiance divided between the Ustaše regime and the Partisans.[65] As a young officer in World War I, Mickl had commanded Croatian soldiers, and knew them to be brave fighters. In that war, Croats had served in a multi-ethnic army under Austrian officers, and they all spoke German well enough to understand and be understood. In contrast, his new command consisted of Croatian soldiers who hardly understood German, and whose patriotism could not be assumed. Mickl saw that instilling German discipline and standards was a second order of business, and that the main role of his officers was to "awaken and maintain their will to fight". Despite an understaffed headquarters, he was fortunate to have Hauptmann der Reserve Bransch as the commander of the divisional reconnaissance battalion. Bransch had served with Mickl since Africa. Mickl decided that he needed a reliable, proven officer as his divisional chief of operations, so he arranged for Bransch to be promoted to Major, and appointed him to lead his operations staff. However, a few days later, Major im Generalstab Gerd Kobe arrived fresh from the Eastern Front. Kobe had served in the operations departments at both corps and army-level, and had experience in working for brave but difficult commanders.[66]

Kobe's introduction to Mickl was abrupt, as the general was very angry at having been left without a chief of operations for so long. Mickl encapsulated his approach to command in this way:[67]

My place is with the guns! You will maintain the division for me. From time to time we will speak by telephone or radio. If we have an understanding on this, everything will be good. If not, then you will have to go.

Mickl's first order to Kobe was to contact the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, who lived in Berlin, to request an imam for the division, as the division included a company of infantry and a battery of artillery staffed by Bosnian Muslims. Soon after Kobe arrived, Mickl departed on leave for the Christmas and New Year period, leaving Kobe to arrange the rail transport of the division to its initial deployment area, 50 km (31 mi) southwest of Zagreb.[67]

Initial clearing operations

The division was deployed to the NDH by rail between 5 and 10 January 1944,[68] to combat the Partisans in the western parts of the puppet state.[69] It became known as the "Blue Division" (German: Blaue Division, Croatian: Plava divizija),[61] as its first deployment was within view of the Adriatic.[70] Mickl's task was well known to the Partisans,[59] and focused on securing the Adriatic coastline along the Croatian Littoral between Rijeka and Karlobag (including all islands except Krk) and about 60 km (37 mi) inland. This task included securing the crucial supply route between Karlovac and Senj. These areas, and in particular the port of Senj, had been largely dominated by the Partisans since the Italian capitulation in autumn 1943. Mickl's division was placed under the command of the XV Mountain Corps as part of the 2nd Panzer Army, with its headquarters to be established in Karlovac. The division was also to take over responsibility for the security of the Zagreb–Karlovac railway line from the 1st Cossack Division.[27] Before the division had completed detraining at Zagreb, its lead elements had been pressed into service to clear the Partisans from the nearby village of Žumberak.[71]

When Mickl arrived by train in Zagreb on 12 January, Kobe met him at the station and informed him that he was ready for Mickl to decide the time that an attack against Partisan forces besieging the NDH garrison at Ogulin near Karlovac should be launched. In response, Mickl grinned and shook Kobe's hand, and according to Kobe, "the spell was broken", and from that time on, Mickl and his chief of operations had a very good working relationship.[71] The operation involved a drive southwest from Karlovac between 13 and 16 January 1944 initially led by the 847th Infantry Regiment. In their first engagements with the Partisan 8th Division, the Croatian soldiers panicked and their German leaders were quickly wounded or killed, but Mickl went forward and ensured that his troops pressed home their attacks. On 16 January, Ogulin was relieved, but the advance was continued south to Skradnik, and villages in that area were also secured. When the bodies of those that had been killed were recovered, they were often found stripped of equipment and some were even found naked.[72] This success in their first operation gave the inexperienced Croat soldiers greater confidence in themselves and their commanders.[73]

This was followed by Operation Drežnica, a push through to the coast, forcing passes through the Velika Kapela mountain range, part of the Dinaric Alps. Both passes were more than 750 metres (2,460 ft) above sea level and the snow was often knee or thigh-deep. Delayed by mines and roadblocks, the division captured the Kapela and Vratnik passes with Mickl ensuring that his troops worked carefully in order to minimise casualties. After the first few days of fighting, XV Mountain Corps and 2nd Panzer Army began to urge Mickl to advance faster, but he resisted this, knowing that his division was inexperienced. This was followed by a series of engagements along the road to the coast, and after some close quarter fighting with the Partisan 13th Division, they captured and destroyed most of that division's supply dump northwest of Lokve and secured Senj. The 847th Infantry Regiment was then allocated the task of securing the coastline up the coast as far as Bakar, and southward to the village of Jablanac, and the 846th Infantry Regiment was directed to secure the divisional supply route from Senj to Generalski Stol. They started improving bases along the road, including Italian forts that had been established in the Kapela and Vratnik passes. The 847th Infantry Regiment then spread out along the coastline between Karlobag and Crikvenica, and supported by elements of the divisional artillery and pioneers they began building fortifications against a feared Allied invasion. The troops in Karlobag linked up with the 264th Infantry Division who were responsible for the coast further to the southeast. The supply situation quickly became difficult due to Partisan interdiction of the route from Karlovac, and Allied bombing of coastal shipping and Senj harbour.[74][75]

Fighting during 1944

In late February or early March the 847th Infantry Regiment, supported by an Ustaše battalion, advanced on Plaški (south of Ogulin) when they were stopped by deep snow. Partisans then attacked their supply lines, killing 30 soldiers. Some of the bodies of the dead soldiers were looted or mutilated. After Plaški was captured, the Ustaše battalion independently pursued the Partisans and returned to Plaški with many of the looted items.[76] In March, the 847th Regiment occupied the Adriatic islands of Rab and Pag without encountering any Partisan resistance. In the same month, the 846th Regiment conducted an operation in the Gacka river valley around Otočac, and assisted the Croatian Home Guard in enforcing conscription orders on their own population in the divisional area. Through the spring of 1944, the 846th Regiment used jadgkommandos, lightly armed and mobile "hunter teams" of company or battalion strength, to conduct follow-up of sightings of Partisans, and transport moving through the Kapela Pass had to travel in convoy for security. The division was able to restore a land connection with the NDH garrison of Gospić which had been reliant on supply from the sea since the Italian surrender, and drove three Partisan battalions out of the outskirts of Otočac.[77] One of the difficulties faced by the division in fighting in the mountains was the lack of mountain artillery which could accompany the battalions in the field. The divisional artillery was equipped with field howitzers with a range of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) which seriously limited the artillery cover that could be provided during mobile operations.[78]

In March, the 847th Regiment occupied the Adriatic islands of Rab and Pag without encountering any Partisan resistance. In the same month, the 846th Regiment conducted an operation in the Gacka river valley around Otočac, and assisted the Croatian Home Guard in enforcing conscription orders on their own population in the divisional area. Through the spring of 1944, the 846th Regiment used jadgkommandos, lightly armed and mobile "hunter teams" of company or battalion strength, to conduct follow-up of sightings of Partisans, and transport moving through the Kapela Pass had to travel in convoy for security. The division was able to restore a land connection with the NDH garrison of Gospić which had been reliant on supply from the sea since the Italian surrender, and drove three Partisan battalions out of the outskirts of Otočac.[77] One of the difficulties faced by the division in fighting in the mountains was the lack of mountain artillery which could accompany the battalions in the field. The divisional artillery was equipped with field howitzers with a range of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) which seriously limited the artillery cover that could be provided during mobile operations.[78]

On 1 April 1944, Mickl was promoted to Generalleutnant.[27] He identified that the Partisan 13th Division was using the Drežnica valley as a huge armoury, hiding captured Italian arms and ammunition in villages, basements, and even in fake graves in cemeteries. This was of major concern if the feared Allied landing eventuated.[79] In mid-April, Mickl ordered Operation Keulenschlag (Mace Blow) to clear the area, using the 846th Infantry Regiment and parts of the 847th Infantry Regiment, supported by the divisional artillery and flak battalion. Over the next two weeks, the division pushed the Partisan 13th Division north to the area of Mrkopalj and Delnice, and captured sufficient material to equip two divisions, including 30 tons of small arms ammunition and 15 tons of artillery ammunition.[80]

The Partisan 35th Division attacked from the Plitvice Lakes area on 5 May and captured the village of Ramljane. Partisans also interdicted the Otočac-Gospić road.[81] In response, Mickl planned Operation Morgenstern (Morning Star) to clear Partisan forces from the Krbavsko Polje region around Udbina. From 7 to 16 May 1944, along with elements of the 373rd (Croatian) Infantry Division, the 92nd Motorised Regiment, a battalion of the 1st Regiment of the Brandenburg Division, and Ustaše units, were involved in Operation Morgenstern. According to German sources, Operation Morgenstern resulted in significant Partisan losses, including 438 killed, 56 captured, and 18 defectors, as well as capturing weapons, ammunition, vehicles, animals and large amounts of equipment.[82] For its efforts in this operation, the division received its first mention in the Wehrmachtbericht (armed forces daily radio broadcast).[83] Also in May, the division received 500 German reinforcements, and formed a field replacement battalion.[84]

The population of some areas secured by the division had a high proportion of Serbs, a situation that had arisen when the area was part of the Military Frontier between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Once the division had secured its area of responsibility, it became clear to the members of the division that a fratricidal war had been raging between Croats and Serbs. Both Roman Catholic and Serbian Orthodox churches had been destroyed, and elements of the division would observe smoke in the valleys occupied by Serbs, and upon investigation, would find burned houses and dead and wounded Serb civilians. Mickl was indignant about these attacks, and summoned all the Croatian civil and military leadership in the divisional area to his headquarters. In the meantime, he ordered two battalions of the division away from their positions on the eastern side of Otočac. When the Croatian officials arrived at his headquarters, they protested that he had exposed Otočac to attack. Incensed, Mickl shouted at them, "Are you officers and soldiers, or robbers and murderers?", and threatened to withdraw the whole division to the coast, leaving the whole area undefended. The Croatian functionaries swore that the perpetrators of the attacks had been punished and that they would ensure that they would not occur in future. Nevertheless, Mickl kept garrisons in the Serb-populated valleys for many weeks in order to protect the Serbs from their Croat neighbours.[85]

The division saw action against the Partisans until the end of the war,[61] often fighting alongside a grouping of Ustaše units that numbered up to 12,000 troops.[60]

Death and legacy

During the last few months of the war, the division was engaged in the defence of the northern Adriatic coast and Lika.[86] On 8 April 1945, the city of Senj fell to the Partisans. The following day, during desperate fighting to control the Vratnik pass through the mountains from Senj to Brinje, Mickl personally took part in the fighting and was shot in the head around noon. He was transported to hospital in Rijeka on a tank, but died the following day.[87][lower-alpha 2]

Oberstleutnant Kobe, the chief operations officer of the 392nd Division, described Mickl as "a giant in stature, lean and muscular despite his 50 years", a very demanding commander who was also very demanding of himself. Kobe stated that Mickl was frequently at the forefront of the fighting, carrying a Gewehr 43 carbine.[89] In 1967,[5] the Austrian Armed Forces barracks (Mickl-Kaserne) in Bad Radkersburg were named after him, and they were used continuously by the Austrian Armed Forces for 44 years until 30 September 2008.[90]

Promotions

- Leutnant – 1 August 1914[27]

- Oberleutnant – 1 May 1915[27]

- Hauptmann – 1921[5]

- Major – 1928[26]

- Oberstleutnant – 16 January 1936[27]

- Oberst – 1 June 1940[27]

- Generalmajor – 1 March 1943[40]

- Generalleutnant – 1 April 1944[27]

Awards and decorations

Austria-Hungary

- Military Merit Cross 3rd Class (16 October 1915)[17]

- Order of the Iron Crown 3rd Class (22 March 1916)[17]

- Military Merit Medal for Bravery

- Karl Troop Cross (8 September 1917)[17]

- Wound Medal with 5 Stripes (10 March 1918)[17]

Carinthia

- Common Carinthian Cross for Bravery (5 December 1919)[17]

- Special Carinthian Cross for Bravery (3 April 1920)[17]

Federal State of Austria

- Medal of Merit in Gold (7 October 1934)[17]

Third Reich

- Iron Cross (1939)

- Panzer Badge in Bronze (24 September 1940)[17]

- Wound Badge in Black (25 December 1941)[17]

- Infantry Assault Badge (22 July 1942)[17]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

Notes

- ↑ Manfred and his fiancée were both killed by an aerial bomb on 25 September 1944 in Vienna. He had been on his way to see his father to ask for his consent to get married.[43]

- ↑ Mickl's wife, Helene, died in July 1946 of cancer.[88]

- ↑ According to Von Seemen as leader of Schützen-Regiment 155 Afrika.[93]

Footnotes

- ↑ Richter 1994, pp. 456–457.

- 1 2 3 4 Mitcham 2007, p. 147.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 13, 35.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 17, 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Richter 1994, p. 457.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 17.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 18–21.

- 1 2 3 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 21.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 22.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 23.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 24.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 28.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 30.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 30–32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 Egger 1974, p. 265.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 34.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 83.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 46.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 86.

- ↑ Egger 1974, pp. 265–266.

- 1 2 3 Egger 1974, p. 266.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Glaise von Horstenau 1980, p. 348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mitcham 2007, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Thomas 1998, p. 81.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 96.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 97.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 98.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 98 & 100.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 100.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 102.

- ↑ Mitcham 2007, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mitcham 2007, p. 151.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 135.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 105.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 109.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 110–112.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Newton 2009, p. 76.

- ↑ Fanghor 2002, pp. 75–77.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fanghor 2002, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 113.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 114.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 116.

- ↑ Mitcham 2007, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 117.

- 1 2 Schraml 1962, p. 230.

- 1 2 3 Tomasevich 2001, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 267.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 304.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 120.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 121–123.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 123.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, p. 231.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 118.

- 1 2 Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 124.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 125.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 234–241.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, p. 242.

- 1 2 Schraml 1962, pp. 242–246.

- 1 2 Schraml 1962, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, p. 248.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, p. 186.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 131.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, p. 250.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 463 & 771.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ Richter & Kobe 1983, p. 149.

- ↑ Schraml 1962, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Österreichs Bundesheer 2008.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 311.

- 1 2 Scherzer 2007, p. 544.

- ↑ Von Seemen 1976, p. 241.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 67.

- ↑ Von Seemen 1976, p. 33.

References

- Egger, R. (1974). "Mickl, Johann (1893–1945), Generalmajor". Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950 [Austrian Biographical Encyclopedia] (in German). 6. Vienna, Austria: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-3-7001-3213-4.

- Fanghor, Friedrich (2002). "Fourth Panzer Army". In Newton, Steven H. Kursk: The German View. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. pp. 71–96. ISBN 978-0-306-81150-0.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000). Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund (1980). Broucek, Peter, ed. Ein General im Zwielicht: K.u.k. Generalstabsoffizier und Historiker [A General in the Twilight: K.u.k. General staff officer and historian] (in German). Vienna, Austria: Böhlau Verlag Wien. ISBN 978-3-205-08740-3.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2007). Rommel's Lieutenants: The Men Who Served the Desert Fox, France, 1940. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International. ISBN 978-0-275-99185-2.

- Newton, Steven H. (2009). Kursk: The German View. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-4513-5.

- Nipe, George M. (2011). Blood, Steel, & Myth : The II. SS-Panzer-Korps and the road to Prochorowka, July 1943. Southbury, Connecticut: Newbury. ISBN 978-0-9748389-4-6.

- Österreichs Bundesheer (2008). "Ende der militärischen Nutzung der Mickl-Kaserne" [End of the military use of Mickl Barracks] (in German). Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Richter, Heinz (1994). "Mickl (eigentlich Mikl), Johann". Neue deutsche Biographie, Melander – Moller [New German Biography, Melander – Moller] (in German). 17. Berlin, Germany: Duncker & Humblot. pp. 456–457. ISBN 978-3-428-00286-3.

- Richter, Heinz; Kobe, Gerd (1983). Bei den Gewehren—General Johann Mickl—Ein Soldatenschicksal [With the Guns—General Johann Mickl—A Soldiers Fate] (in German). Bad Radkersburg, Austria: Selbstverlag der Stadt Bad Radkersburg. ASIN B003DKFQUS (12 September 2013).

- Schraml, Franz (1962). Kriegsschauplatz Kroatien die deutsch-kroatischen Legions-Divisionen: 369., 373., 392. Inf.-Div. (kroat.) ihre Ausbildungs- und Ersatzformationen [The Croatian Theatre of War: German-Croatian Legion divisions: the 369th, 373rd and 392nd (Croatian) Infantry Divisions and their Training and Replacement Units] (in German). Neckargemünd, Germany: K. Vowinckel. OCLC 4215438.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Von Seemen, Gerhard (1976). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 : die Ritterkreuzträger sämtlicher Wehrmachtteile, Brillanten-, Schwerter- und Eichenlaubträger in der Reihenfolge der Verleihung : Anhang mit Verleihungsbestimmungen und weiteren Angaben [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 : The Knight's Cross Bearers of All the Armed Services, Diamonds, Swords and Oak Leaves Bearers in the Order of Presentation: Appendix with Further Information and Presentation Requirements] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7909-0051-4.

- Thomas, Franz (1998). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 2: L–Z [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2300-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. 2. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Generalmajor Max Sümmermann † |

Commander of 90th Light Infantry Division 11 December 1941 – 27 December 1941 |

Succeeded by Generalmajor Richard Veith |

| Preceded by General der Infanterie Dietrich von Choltitz |

Commander of 11th Panzer Division 11 May 1943 – 8 August 1943 |

Succeeded by Generalleutnant Wend von Wietersheim |

| Preceded by None |

Commander of 392nd (Croatian) Infantry Division 17 August 1943 – 10 April 1945 |

Succeeded by None |