Kuršumlija

| Kuršumlija Куршумлија | ||

|---|---|---|

| Municipality and Town | ||

|

Panoramic view on Kuršumlija | ||

| ||

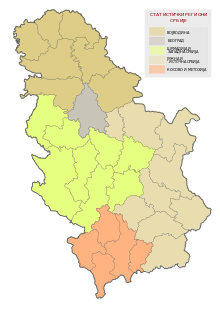

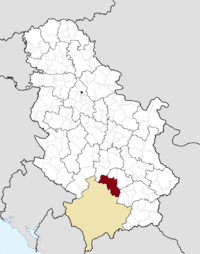

Location of the municipality of Kuršumlija within Serbia | ||

| Coordinates: 43°09′N 21°16′E / 43.150°N 21.267°ECoordinates: 43°09′N 21°16′E / 43.150°N 21.267°E | ||

| Country | Serbia | |

| District | Toplica | |

| Settlements | 90 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Goran Bojović | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Municipality | 952 km2 (368 sq mi) | |

| Population (2011 census)[2] | ||

| • Town | 13,306 | |

| • Municipality | 19,213 | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 18430 | |

| Area code | +381 27 | |

| Car plates | PK | |

| Website |

www | |

Kuršumlija (Serbian Cyrillic: Куршумлија, pronounced [kurʃǔmlija]) is a town and municipality located in Serbia, near the rivers Toplica, Kosanica and Banjska, on the southeast of mount Kopaonik, and northwest of Mount Radan. As of 2011, the town has 13,306 inhabitants, while municipality has 19,213.

Geography

Kuršumlija sits on the area of 952 km2 (367.57 sq mi) and administratively is in Toplica District. Its borders the municipalities of Brus, Blace, Prokuplje, Medveđa, Podujevo, and Leposavić. Its southwest border (105 km) is within the disputed territory of Kosovo.

History

The Romans established the Ad Fines military outpost in the 3rd century AD. There are also remains of churches from the Byzantine period. The Serbian principality of Rascia expanded from this region. Stefan Nemanja, a Serbian lord (župan), and the founder of Nemanjić dynasty, built his residence here, as well as the two monasteries of St Nicolas and the Holy Mother of God (before 1168).

There are many historical sights in Kuršumlija from that era: Mara Tower, Ivan Tower, and many medieval churches. The name in that period was Bele Crkve (White Churches) and Toplica. After the invasion by the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century, the Ottomans gave the town its current name, simply by translating the old name, Bele Crkve (White Churches). During Ottoman rule Kuršumlija was part of the Sanjak of Niš.[3]

Toponyms such as Arbanaška and Đjake shows an Albanian presence in the Toplica and Southern Morava regions (located north-east of contemporary Kosovo) before the expulsion of Albanians during 1877–78 period.[4][5]

The rural parts of Toplica valley and adjoining semi-mountainous interior was inhabited by compact Muslim Albanian population while Serbs in those areas lived near the river mouths and mountain slopes and both peoples inhabited other regions of the South Morava river basin.[6][7]

As the wider Toplica region,[8] Kuršumlija also had an Albanian majority.[9][10] These Albanians were expelled by Serbian forces[11][12][13] in a way that today would be characterized as ethnic cleansing.[14]

In 1878, Kuršumlija became a part of the Principality of Serbia, which in 1882 became the Kingdom of Serbia. From 1929-41, Kuršumlija was part of the Morava Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Features

.jpg)

Kuršumlija is known for a natural monument of hoodoos near Mount Radan known as Đavolja Varoš ('Devil's Town'). There are three spas (banjas): the Prolom Banja, Kuršumlijska Banja, and Lukovska Banja. Prolom water is bottled at the Prolom Spa.

Demographics

Kuršumlija Municipality include one urban and 89 rural settlements. According to the 2011 census there are 19,213 inhabitants in the municipality.

Ethnic groups in the municipality:

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 18,528 |

| Roma | 339 |

| Montenegrins | 47 |

| Others | 299 |

| Total | 19,213 |

Notable natives or residents

.jpg)

- The most notable Grand Prince of Serbia, Stefan Nemanja, established his first capital, Bele Crkve, near the location of today's Kuršumlija in 1166–1172. His wife, Grand Princess Anastasia (Ana), died and was buried here as a nun, St. Anastasia Nemanjic.

- Sultania Mara, daughter of Despot Đurađ Branković, later wife of the Ottoman Emperor Murad II, and step mother of Emperor Mehmed II also at the end of her life came to live here as a nun in monastery of Holy Mother of God, where she made a fortress called Mara Tower. She died in around 1487.

- Kosta Pećanac, a notable Serbian soldier in the First and Second World War. His house is protected of by the municipality.

- Dragoljub Mićunović (born in 1930. in Merdare, Kuršumlija), professor of at the University of Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy. He was a dissident during the Communist period, and the first president of the Democratic Party. He was the first president of parliament of State Union of Serbia & Montenegro.

- Momčilo Đokić, He played a total of 13 matches for the Yugoslavia national football team. His debut was on April 13, 1930 against Bulgaria, in Belgrade, a 6-1 win, and his fairway match was on December 13, 1936, in Paris against France, a 0-1 loss. He played all the matches at the 1930 FIFA World Cup in Uruguay.

- Žarko Dragojević, director, born in Kuršumlija, professor at the Faculty of Drama at the University of Belgrade. He is director of several notable films: Kuća pored pruge (House by the tracks), Noć u kući moje majke (Night in my mother's house). He also directed many documentaries, among them series on Serbian monasteries for the Serbian national broadcaster (RTS).

- Vojin Šulović, academician, humanist, doctor of gynaecology. 7 July and October awards of city of Belgrade winner. Also Serbian medical society award winner and Serbian warrior medallist. Smederevo and Kuršumlija municipality freeman.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ↑ Godišnjak grada Beograda. Museum of the Belgrade. 1977. p. 116. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Uka, Sabit (2004). Jeta dhe veprimtaria e shqiptarëve të Sanxhakut të Nishit deri më 1912 [Life and activity of Albanians in the Sanjak of Nish up to 1912]. Verana. pp. 244–45; ISBN 9789951864527. "Eshtë, po ashtu, me peshë historike një shënim i M. Gj Miliçeviqit, i cili bën fjalë përkitazi me Ivan Begun. Ivan Begu, sipas tij ishte pjesëmarrës në Luftën e Kosovës 1389. Në mbështetje të vendbanimit të tij, Ivan Kullës, fshati emërtohet Ivan Kulla (Kulla e Ivanit), që gjendet në mes të Kurshumlisë dhe Prokuplës. M. Gj. Miliçeviqi thotë: "Shqiptarët e ruajten fshatin Ivan Kullë (1877–1878) dhe nuk lejuan që të shkatërrohet ajo". Ata, shqiptaret e Ivan Kullës (1877–1878) i thanë M. Gj. Miliçeviqit se janë aty që nga para Luftës se Kosovës (1389). [12] Dhe treguan që trupat e arrave, që ndodhen aty, ata i pat mbjellë Ivan beu. Atypari, në malin Gjakë, nodhet kështjella që i shërbeu Ivanit (Gjonit) dhe shqiptarëve për t’u mbrojtur. Aty ka pasur gjurma jo vetëm nga shekulli XIII dhe XIV, por edhe të shekullit XV ku vërehen gjurmat mjaft të shumta toponimike si fshati Arbanashka, lumi Arbanashka, mali Arbanashka, fshati Gjakë, mali Gjakë e tjerë. [13] Në shekullin XVI përmendet lagja shqiptare Pllanë jo larg Prokuplës. [14] Ne këtë shekull përmenden edhe shqiptarët katolike në qytetin Prokuplë, në Nish, në Prishtinë dhe në Bulgari.[15].... [12] M. Đj. Miličević. Kralevina Srbije, Novi Krajevi. Beograd, 1884: 354. "Kur flet mbi fshatin Ivankullë cekë se banorët shqiptarë ndodheshin aty prej Betejës së Kosovës 1389. Banorët e Ivankullës në krye me Ivan Begun jetojnë aty prej shek. XIV dhe janë me origjinë shqiptare. Shqiptarët u takojnë të tri konfesioneve, por shumica e tyre i takojnë atij musliman, mandej ortodoks dhe një pakicë i përket konfesionit katolik." [13] Oblast Brankovića, Opširni katastarski popis iz 1455 godine, përgatitur nga M. Handžic, H. Hadžibegić i E. Kovačević, Sarajevo, 1972: 216. [14] Skënder Rizaj, T,K "Perparimi" i vitit XIX, Prishtinë 1973: 57.[15] Jovan M. Tomić, O Arnautima u Srbiji, Beograd, 1913: 13. [It is, as such, of historic weight in a footnote of M. Đj. Miličević, who says a few words regarding Ivan Beg. Ivan Beg, according to him participated in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. In support of his residence, Ivan Kula, the village was named Ivan Kula (Tower of Ivan), located in the middle of Kuršumlija and Prokuple. M. Đj. Miličević says: "Albanians safeguarded the village Ivan Kula (1877–1878) and did not permit its destruction." Those Albanians of Ivan Kulla (1877–1878) told M.Đj. Miličević that they have been there since before the Kosovo War (1389). And they showed where the bodies of the walnut trees were, that Ivan Bey had planted. Then there to Mount Đjake, is the castle that served Ivan (John) and Albanians used to defend themselves. There were traces not only from the XIII and XIV centuries, but the XV century where we see fairly multiple toponymic traces like the village Arbanaška, river Arbanaška, mountain Arbanaška, village Đjake, mountain Đjake and others. In the sixteenth century mentioned is the Albanian neighborhood Plana not far from Prokuple. [14] In this century is mentioned also Catholic Albanians in the town of Prokuplje, Niš, Priština and in Bulgaria.[15].... [12] M. Đj. Miličević. Kralevina Srbije, Novi Krajevi. Beograd, 1884: 354. When speaking about the village Ivankula, its residents state that Albanians were there from the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Residents of Ivankula headed by Ivan Beg are living there since the XIV century and they are of Albanian origin. Albanians belong to three religions, but most of them belong to the Muslim one, after Orthodoxy and then a minority belongs to the Catholic confession. [13] Oblast Brankovića, Opširni katastarski popis iz 1455 godine, përgatitur nga M. Handžic, H. Hadžibegić i E. Kovačević, Sarajevo, 1972: 216. [14] Skënder Rizaj, T,K "Perparimi" i vitit XIX, Prishtinë 1973: 57. [15] Jovan M. Tomić, O Arnautima u Srbiji, Beograd, 1913: 13.]"

- ↑ "Formation of a Diasporic Community: The History of Migration and Resettlement of Muslim Albanians in the Black Sea Region of Turkey: Middle Eastern Studies: Vol 45, No 4". pp. 556–57.

Using secondary sources, we establish that there have been Albanians living in the area of Nish for at least 500 years, that the Ottoman Empire controlled the area from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries which led to many Albanians converting to Islam, that the Muslim Albanians of Nish were forced to leave in 1878, and that at that time most of these Nishan Albanians migrated south into Kosovo, although some went to Skopje in Macedonia.; pg. 557. It is generally believed that the Albanians in Samsun Province are the descendants of the migrants and refugees from Kosovo who arrived in Turkey during the wars of 1912–13. Based on our research in Samsun Province, we argue that this information is partial and misleading. The interviews we conducted with the Albanian families and community leaders in the region and the review of Ottoman history show that part of the Albanian community in Samsun was founded through three stages of successive migrations. The first migration involved the forced removal of Muslim Albanians from the Sancak of Nish in 1878; the second migration occurred when these migrants’ children fled from the massacres in Kosovo in 1912–13 to Anatolia; and the third migration took place between 1913 and 1924 from the scattered villages in Central Anatolia where they were originally placed to the Samsun area in the Black Sea Region. Thus, the Albanian community founded in the 1920s in Samsun was in many ways a reassembling of the demolished Muslim Albanian community of Nish…. Our interviews indicate that Samsun Albanians descend from Albanians who had been living in the villages around the city of Nish… pp. 557–58. In 1690 much of the population of the city and surrounding area was killed or fled, and there was an emigration of Albanians from the Malësia e Madhe (North Central Albania/Eastern Montenegro) and Dukagjin Plateau (Western Kosovo) into Nish.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 9, 32–42, 45–61.

- ↑ Luković, Miloš (2011) "Development of the Modern Serbian state and abolishment of Ottoman Agrarian relations in the 19th century", Český lid. 98. (3): 298. "During the second war (December 1877—January 1878) the Muslim population fled towns (Vranya (Vranje), Leskovac, Ürgüp (Prokuplje), Niş (Niš), Şehirköy (Pirot), etc.) as well as rural settlements where they comprised ethnically compact communities (certain parts of Toplica, Jablanica, Pusta Reka, Masurica and other regions in the South Morava River basin). At the end of the war these Muslim refugees ended up in the region of Kosovo and Metohija, in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, following the demarcation of the new border with the Principality of Serbia. [38] [38] On Muslim refugees (muhaciri) from the regions of southeast Serbia, who relocated in Macedonia and Kosovo, see Trifunovski 1978, Radovanovič 2000."

- ↑ Bataković, Dušan T. (2007). Kosovo and Metohija: living in the enclave, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 35; retrieved 22 June 2011; "Prior to the Second Serbo-Ottoman War (1877-78), Albanians were the majority population in some areas of Sanjak of Nis (Toplica region), while from the Serb majority district of Vranje Albanian-inhabited villages were emptied after the 1877-1878 war"

- ↑ Bataković, Dušan T. (2007). Kosovo and Metohija: living in the enclave. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 35; retrieved 22 June 2011. "Prior to the Second Serbo-Ottoman War (1877-78), Albanians were the majority population in some areas of Sanjak of Nis (Toplica region), while from the Serb majority district of Vranje Albanian-inhabited villages were emptied after the 1877-1878 war"

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 5, 6.

- ↑ Turović, Dobrosav (2002). Gornja Jablanica, Kroz istoriju. Beograd Zavičajno udruženje. pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Uka, Sabit (2004). Gjurmë mbi shqiptarët e Sanxhakut të Nishit deri më 1912 [Traces on Albanians of the Sanjak of Nish up to 1912]. Verana. p. 155; ISBN 9789951864527; "Në kohët e sotme fshatra të Jabllanicës, të banuara kryesisht me shqiptare, janë këto: Tupalla, Kapiti, Gërbavci, Sfirca, Llapashtica e Epërrne. Ndërkaq, fshatra me popullsi te përzier me shqiptar, malazezë dhe serbë, jane këto: Stara Banja, Ramabanja, Banja e Sjarinës, Gjylekreshta (Gjylekari), Sijarina dhe qendra komunale Medvegja. Dy familje shqiptare ndeshen edhe në Iagjen e Marovicës, e quajtur Sinanovë, si dhe disa familje në vetë qendrën e Leskovcit. Vllasa është zyrtarisht lagje e fshatit Gërbavc, Dediqi, është lagje e Medvegjes dhe Dukati, lagje e Sijarinës. Në popull konsiderohen edhe si vendbanime të veçanta. Kështu qendron gjendja demografike e trevës në fjalë, përndryshe para Luftës se Dytë Botërore Sijarina dhe Gjylekari ishin fshatra me populisi të perzier, bile në këtë te fundit ishin shumë familje serbe, kurse tani shumicën e përbëjnë shqiptarët. [In contemporary times, villages in the Jablanica area, inhabited mainly by Albanians, are these: Tupale, Kapiti, Grbavce, Svirca, Gornje Lapaštica. Meanwhile, the mixed villages populated by Albanians, Montenegrins and Serbs, are these: Stara Banja, Ravna Banja, Sjarinska Banja, Đulekrešta (Đulekari) Sijarina and the municipal center Medveđa. Two Albanian families are also encountered in the neighborhood of Marovica called Sinanovo, and some families in the center of Leskovac. Vllasa is formally a neighborhood of the village Grbavce, Dedići is a neighborhood of Medveđa and Dukati, a neighborhood of Sijarina. So this is the demographic situation in question that remains, somewhat different before World War II as Sijarina and Đulekari were villages with mixed populations, even in this latter settlement were many Serb families, and now the majority is made up of Albanians.]"

- ↑ Blumi, Isa (2013). Ottoman refugees, 1878–1939: migration in a post-imperial world. A&C Black, pg. 50; ISBN 9781472515384; "As these Niš refugees waited for acknowledgment from locals, they took measures to ensure that they were properly accommodated by often confiscating food stored in towns. They also simply appropriated lands and began to build shelter on them. A number of cases also point to banditry in the form of livestock raiding and "illegal" hunting in communal forests, all parts of refugees’ repertoire... At this early stage of the crisis, such actions overwhelmed the Ottoman state, with the institution least capable of addressing these issues being the newly created Muhacirin Müdüriyeti... Ignored in the scholarship, these acts of survival by desperate refugees constituted a serious threat to the established Kosovar communities. The leaders of these communities thus spent considerable efforts lobbying the Sultan to do something about the refugees. While these Niš muhacir would in some ways integrate into the larger regional context, as evidenced later, they, and a number of other Albanian-speaking refugees streaming in for the next 20 years from Montenegro and Serbia, constituted a strong opposition block to the Sultan’s rule."; pg. 53; "One can observe that in strategically important areas, the new Serbian state purposefully left the old Ottoman laws intact. More important, when the state wished to enforce its authority, officials felt it necessary to seek the assistance of those with some experience, using the old Ottoman administrative codes to assist judges make rulings. There still remained, however, the problem of the region being largely depopulated as a consequence of the wars... Belgrade needed these people, mostly the landowners of the productive farmlands surrounding these towns, back. In subsequent attempts to lure these economically vital people back, while paying lip-service to the nationalist calls for "purification", Belgrade officials adopted a compromise position that satisfied both economic rationalists who argued that Serbia needed these people and those who wanted to separate "Albanians" from "Serbs". Instead of returning back to their "mixed" villages and towns of the previous Ottoman era, these "Albanians," "Pomoks," and "Turks" were encouraged to move into concentrated clusters of villages in Masurica, and Gornja Jablanica that the Serbian state set up for them. For this "repatriation" to work, however, authorities needed the cooperation of local leaders to help persuade members of their community who were refugees in Ottoman territories to "return." In this regard, the collaboration between Shahid Pasha and the Serbian regime stands out. An Albanian who commanded the Sofia barracks during the war, Shahid Pasha negotiated directly with the future king of Serbia, Prince Milan Obrenović, to secure the safety of those returnees who would settle in the many villages of Gornja Jablanica. To help facilitate such collaborative ventures, laws were needed that would guarantee the safety of these communities likely to be targeted by the rising nationalist elements infiltrating the Serbian army at the time. Indeed, throughout the 1880s, efforts were made to regulate the interaction between exiled Muslim landowners and those local and newly immigrant farmers working their lands. Furthermore, laws passed in early 1880 began a process of managing the resettlement of the region that accommodated those refugees who came from Austrian-controlled Herzegovina and from Bulgaria. Cooperation, in other words, was the preferred form of exchange within the borderland, not violent confrontation."

- ↑ Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941", East Central Europe. 36. (1): 70; "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998; Pllana 1985); Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller, 2005). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- ↑ in memoriam academician Vojin ŠuloViĆ(1923-2008)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kuršumlija. |