Modern Greek phonology

| In IPA, phonemes are written between slashes, / /, and corresponding allophones between brackets, [ ]. |

This article deals with the phonology and phonetics of Standard Modern Greek. For phonological characteristics of other varieties, see varieties of Modern Greek, and for Cypriot, specifically, see Cypriot Greek § Phonology.

Consonants

Greek linguists do not agree on which consonants to count as phonemes in their own right, and which to count as conditional allophones. The table below is adapted from Arvaniti (2007, p. 7), who does away with the entire palatal series, and both affricates [t͡s] and [d͡z].

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | x |

| voiced | v | ð | z | ɣ | |

| Rhotic | r | ||||

| Lateral | l | ||||

| πήρα | /ˈpira/ | 'I took' |

| μπύρα | /ˈbira/ | 'beer' |

| φάση | /ˈfasi/ | 'phase' |

| βάση | /ˈvasi/ | 'base' |

| μόνος | /ˈmonos/ | 'alone' |

| τείνω | /ˈtino/ | 'to tend' |

| ντύνω | /ˈdino/ | 'to dress' |

| θέμα | /ˈθema/ | 'topic' |

| δέμα | /ˈðema/ | 'parcel' |

| σώα | /ˈsoa/ | 'safe' fem. |

| ζώα | /ˈzoa/ | 'animals' |

| νόμος | /ˈnomos/ | 'law' |

| ρήμα | /ˈrima/ | 'verb' |

| λίμα | /ˈlima/ | 'nail file' |

| κόμμα | /ˈkoma/ | 'comma' |

| γκάμα | /ˈɡama/ | 'range' |

| χώμα | /ˈxoma/ | 'soil' |

| γόμα | /ˈɣoma/ | 'eraser' |

The alveolar nasal /n/ is assimilated to following obstruents; it can be labiodental (e.g. αμφιβολία [aɱfivoˈlia] 'doubt'), dental (e.g. άνθος [ˈan̪θos] 'flower'), retracted alveolar (e.g. πένσα [ˈpen̠sa] "pliers"), alveolo-palatal (e.g. συγχύζω [siɲˈçizo] 'to annoy'), or velar (e.g. άγχος [ˈaŋхos] 'stress').[2]

Voiceless stops are unaspirated and with a very short voice onset time.[1] They may be lightly voiced in rapid speech, especially when intervocalic.[3] /t/'s exact place of articulation ranges from alveolar to denti-alveolar, to dental.[4] It may be fricated [θ̠ ~ θ] in rapid speech, and very rarely, in function words, it is deleted.[5] /p/ and /k/ are reduced to lesser degrees in rapid speech.[5]

Voiced stops are prenasalised as reflected in the orthography to varying extents, or not at all.[6] The nasal component—when present—does not increase the duration of the stop's closure; as such, prenasalised voiced stops would be most accurately transcribed [mb nd ŋɡ] or [m͡b, n͡d, ŋ͡ɡ], depending on the length of the nasal component.[6] Word-initially and after /r/ or /l/, they are very rarely, if ever, prenasalised.[1][4] In rapid and casual speech, prenasalisation is generally rarer, and voiced stops may be lenited to fricatives.[4]

/s/ and /z/ are somewhat retracted ([s̠, z̠]); they are produced in between English alveolars /s, z/ and postalveolars /ʃ, ʒ/.[7] /s/ is variably fronted or further retracted depending on environment, and, in some cases, it may be better described as an advanced postalveolar ([ʃ̟]).[7]

The only Greek rhotic /r/ is prototypically an alveolar tap [ɾ], often retracted ([ɾ̠]). It may be an alveolar approximant [ɹ] intervocalically, and is usually a trill [r] in clusters, with two or three short cycles.[8]

Greek has palatals [c, ɟ, ç, ʝ] that contrast with velars [k, ɡ, x, ɣ] before /a, o, u/, but in complementary distribution with velars before front vowels /e, i/.[9] [ʎ] and [r] occur as allophones of /l/ and /n/, respectively, in CJV (consonant–glide–vowel) clusters, in analyses that posit an archiphoneme-like glide /J/ that contrasts with the vowel /i/.[10] All palatals may be analysed in the same way. The palatal stops and fricatives are somewhat retracted, and [ʎ] and [r] are somewhat fronted. [ʎ] is best described as a postalveolar, and [r] as alveolo-palatal.[11]

Finally, Greek has two phonetically affricate[12] clusters, [t͡s] and [d͡z].[13] Arvaniti (2007) is reluctant to treat these as phonemes on the grounds of inconclusive research into their phonological behaviour.[14]

The table below, adapted from Arvaniti (2007, p. 25), displays a near-full array of consonant phones in Standard Modern Greek.

| Consonant phones |

|---|

Sandhi

Some assimilatory processes mentioned above also occur across word boundaries. In particular, this goes for a number of grammatical words ending in /n/, most notably the negation particles δεν and μην and the accusative forms of the personal pronoun and definite article τον and την. If these words are followed by a voiceless stop, /n/ either assimilates for place of articulation to the stop, or is altogether deleted, and the stop becomes voiced. This results in pronunciations such as τον πατέρα [to(m)baˈtera] ('the father' ACC) or δεν πειράζει [ðe(m)biˈrazi] ('it doesn't matter'), instead of *[ton paˈtera] and *[ðen piˈrazi]. The precise extent of assimilation may vary according to dialect, speed and formality of speech.[15]

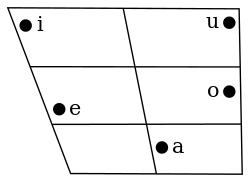

Vowels

Greek has a simple system of five vowels /a, e, i, o, u/.[16] /a/ is best described as near-open central [ɐ], /i/ and /u/ have qualities approaching their respective cardinal vowels, and /e/ and /o/ are, broadly, mid vowels.[16][17] There is no phonemic length distinction, but vowels in stressed syllables are pronounced somewhat longer than in unstressed syllables. Furthermore, vowels in stressed syllables are more peripheral, but the difference is not large.[18]

In casual speech, unstressed /i/ and /u/ in the vicinity of voiceless consonants may become devoiced or even elided.[19]

| πας | /pas/ | 'you go' subj. |

| πες | /pes/ | 'say' imper. |

| πεις | /pis/ | 'you say' subj. |

| πως | /pos/ | 'how' |

| που | /pu/ | 'where' |

Stress

Unlike Ancient Greek, which had a pitch accent system, Modern Greek has variable (phonologically unpredictable) stress. Every multisyllabic word carries stress on one of its three final syllables. Enclitics form a single phonological word together with the host word to which they attach, and count towards the three-syllable rule too. In these cases, primary stress shifts to the second-to-last syllable (e.g. αυτοκίνητό μου [aftoˌciniˈto mu] 'my car'). Phonetically, stressed syllables are longer and/or carry higher amplitude.[18]

The position of the stress can vary between different inflectional forms of the same word within its inflectional paradigm. In some paradigms, the stress is always on the third last syllable, shifting its position in those forms that have longer affixes (e.g. κάλεσα 'I called' vs. καλέσαμε 'we called'; πρόβλημα 'problem' vs. προβλήματα 'problems'). In some word classes, stress position also preserves an older pattern inherited from Ancient Greek, according to which a word could not be accented on the third-from-last syllable if the last syllable was long, e.g. άνθρωπος ('man', nom. sg., last syllable short), but ανθρώπων ('of men', gen. pl., last syllable long). However, in Modern Greek this rule is no longer automatic and does not apply to all words (e.g. καλόγερος 'monk', καλόγερων 'of monks'), as the phonological length distinction itself no longer exists.[20]

Sample

This sample text, the fable of The North Wind and the Sun in Greek, and the accompanying transcription are adapted from Arvaniti (1999, pp. 5–6).

Orthographic version

Ο βοριάς κι ο ήλιος μάλωναν για το ποιος απ’ τους δυο είναι ο δυνατότερος,

όταν έτυχε να περάσει από μπροστά τους ένας ταξιδιώτης που φορούσε κάπα.

Όταν τον είδαν, ο βοριάς κι ο ήλιος συμφώνησαν

ότι όποιος έκανε τον ταξιδιώτη να βγάλει την κάπα του

θα θεωρούνταν ο πιο δυνατός.

Ο βοριάς άρχισε τότε να φυσάει με μανία,

αλλά όσο περισσότερο φυσούσε

τόσο περισσότερο τυλιγόταν με την κάπα του ο ταξιδιώτης,

ώσπου ο βοριάς κουράστηκε και σταμάτησε να φυσάει.

Τότε ο ήλιος άρχισε με τη σειρά του να λάμπει δυνατά

και γρήγορα ο ταξιδιώτης ζεστάθηκε κι έβγαλε την κάπα του.

Έτσι ο βοριάς αναγκάστηκε να παραδεχτεί

ότι ο ήλιος είναι πιο δυνατός απ’ αυτόν.

Transcription

[o voˈɾʝas ˈco̯iʎoz ˈmalonan | ʝa to ˈpços aptuz ˈðʝo ˈin o ðinaˈtoteɾos |

ˈota ˈnetiçe na peˈɾasi apo broˈsta tus | ˈenas taksiˈðʝotis pu̥ foˈɾuse ˈkapa ‖

ˈotan to ˈniðan | o voˈɾʝas ˈco̯iʎo siɱˈfonisan |

oˈti̯opço ˈsekane to ndaksiˈðʝoti na ˈvɣali ti ŋˈɡapa tu |

θa θeoˈɾundan o ˈpço ðinaˈtos ‖

o voˈɾʝas ˈaɾçise ˈtote na fiˈsai me maˈnia |

aˈla̯oso periˈsoteɾo fiˈsuse |

ˈtoso periˈsoteɾo tiliˈɣotan me ti ŋˈɡapa tu̯o taksiˈðjotis |

oˈspu o voˈɾʝas kuˈɾastice ce staˈmati̥se na fi̥ˈsai ‖

ˈtote ˈo̯iʎo ˈsaɾçise me ti siˈɾa tu na ˈlambi ðinaˈta |

ce ˈɣriɣoɾa̯o taksiˈðʝotis zeˈstaθi̥ce ˈc evɣale ti ŋˈɡapa tu ‖

ˈet͡si o voˈɾʝas anaˈŋɡastice na paɾaðeˈxti |

ˈoti ˈo̯iʎos ˈine ˈpço ðinaˈtos ap aˈfton ‖]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Arvaniti 1999, p. 2.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Arvaniti 2007, p. 10.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 2007, p. 11.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 2007, p. 9.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ Baltazani & Topinzi 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 19–20.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Joseph & Philippaki-Warburton 1987, p. 246.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 2007, p. 25.

- ↑ Arvaniti 2007, p. 28.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 1999, p. 5.

- 1 2 Arvaniti 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ Holton, Mackridge & Philippaki-Warburton 1998, pp. 25–27, 53–54.

References

- Arvaniti, Amalia (1999). "Illustrations of the IPA: Modern Greek" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 29: 167–172. doi:10.1017/s0025100300006538.

- Arvaniti, Amalia (2007). "Greek Phonetics: The State of the Art" (PDF). Journal of Greek Linguistics. 8: 97–208. doi:10.1075/jgl.8.08arv.

- Baltazani, Mary; Topinzi, Nina (2013). "Where the glide meets the palatals" (PDF). Selected Papers of the 20th International Symposium of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. Versita.

- Holton, David; Mackridge, Peter; Philippaki-Warburton, Irini (1998). Grammatiki tis ellinikis glossas. Athens: Pataki.

- Joseph, Brian; Philippaki-Warburton, Irene (1987). Modern Greek. Beckenham: Croom Helm.

Further reading

- Adaktylos, Anna-Maria (2007). "The accent of Ancient and Modern Greek from a typological perspective" (PDF). In Tsoulas, George. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Greek Linguistics.

- Arvaniti, Amalia; Ladd, D. Robbert (2009). "Greek wh-questions and the phonology of intonation" (PDF). Phonology. 26: 43–74. doi:10.1017/s0952675709001717.

- Baltazari, Mary (2007). "Prosodic Rhythm and the status of vowel reduction in Greek" (PDF). Selected Papers on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics from the 17th International Symposium on Theoretical & Applied Linguistics. 1. Thessaloniki: Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. pp. 31–43.

- Joseph, Brian D.; Tserdanelis, Georgios (2003). "Modern Greek". In Roelcke, Thorsten. Variationstypologie. Ein sprachtypologisches Handbuch der europäischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart / Variation Typology. A Typological Handbook of European Languages (PDF). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 823–836. ISBN 9783110202021.

- Kong, Eunjong; Beckman, Mary; Edwards, Jan (6–10 August 2007). "Fine-grained phonetics and acquisition of Greek voiced stops" (PDF). Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences.

- Mennen, Ineke; Olakidou, Areti (2006). Acquisition of Greek phonology: an overview. QMU Speech Science Research Centre Working Papers (WP-11).

- Nicolaidis, Katerina; Edwards, Jan; Beckman, Mary; Tserdanelis, Georgios (18–21 September 2003). "Acquisition of lingual obstruents in Greek" (PDF). Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Greek Linguistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2009.

- Trudgill, Peter (2009). "Greek Dialect Vowel Systems, Vowel Dispersion Theory, and Sociolinguistic Typology". Journal of Greek Linguistics. 9 (1): 80–97. doi:10.1163/156658409X12500896406041.