Sappho

Sappho (/ˈsæfoʊ/; Attic Greek Σαπφώ [sapːʰɔ̌ː], Aeolic Greek Ψάπφω, Psappho [psápːʰɔː]) (c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an archaic Greece poet from the island of Lesbos.[lower-alpha 1] Sappho's poetry was lyric poetry, and she is best known for her poems about love. Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and survives only in fragmentary form. As well as lyric poetry, three epigrams attributed to Sappho are preserved, but these are in fact Hellenistic imitations.

Little is known of Sappho's life. She was from a wealthy family from Lesbos, though the names of both of her parents are uncertain. Ancient sources say that she had three brothers; the names of two of them are mentioned in the Brothers Poem discovered in 2014. She was exiled to Sicily around 600 BC, and may have continued to work until around 570.

Sappho's poetry was well-known and greatly admired through much of antiquity, and she was considered one of the canon of nine lyric poets. Today, Sappho's poetry is still considered extraordinary, and her works have continued to influence other writers up until the modern day. Outside of academic circles, she is perhaps best known as a symbol of same-sex desire, particularly between women.

Life

Little is known about Sappho's life for certain – so little that Monique Wittig and Sande Zeig's Lesbian Peoples: Material for a Dictionary contains an entire page for the entry on Sappho, deliberately left blank.[1] There are three major sources of information about Sappho's life: her own poetry, other ancient sources, and deductions from our knowledge of the historical context in which Sappho worked.[2]

The only contemporary source for Sappho's life is her own poetry, and scholars are skeptical of reading it biographically.[3] The other ancient sources on Sappho (known as testimonia) do not date from Sappho's lifetime;[lower-alpha 2] however, they were written by people who had much better access to Sappho's poetry than we do today, and so would have been better placed to use it to write her biography.[3] Despite this, though they are a valuable source on the reception of Sappho in antiquity,[5] it is difficult to assess how accurate a picture they paint of Sappho's life.[3] The testimonia are almost entirely derived from Sappho's poetry, and the inferences made by ancient scholars and reported in the testimonia are in many cases known to be wrong.[6] Holt Parker argues that the testimonia are "valueless" as evidence of Sappho's life,[7] though other scholars are less critical – Rayor and Lardinois suggest that the evidence in the testimonia should be considered "possibly valuable information".[3]

Sappho was from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos,[8][lower-alpha 3] and was probably born around 630 BC.[10][lower-alpha 4] Tradition names her mother as Cleïs,[12] though ancient scholars may simply have guessed this name for Sappho's mother, assuming that Sappho's daughter Cleïs was named after her.[4] Sappho's father's name is less certain. The Suda gives eight possible names;[lower-alpha 5] suggesting that he was not explicitly named in any of Sappho's poetry.[15] In Ovid's Heroides, Sappho's father died when she was seven;[16] Campbell suggests that this may have been based on a now-lost poem of Sappho.[17]

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to Athenaeus, Sappho often praised Larichus for pouring wine in the town hall of Mytilene, an office held by boys of the best families.[18] This indication that Sappho was born into an aristocratic family is consistent with the sometimes rarefied environments that her verses record. One ancient tradition tells of a relation between Charaxus and the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis. Herodotus, the oldest source of the story, reports that Charaxus ransomed Rhodopis for a large sum and that Sappho wrote a poem rebuking him for this.[lower-alpha 6][20]

Sappho may have had a daughter called Cleïs, who is referred to in two fragments.[13] Not all scholars accept that Cleïs was Sappho's daughter, however; fragment 132 describes Cleïs as "παις" (pais), which as well as meaning child can also refer to the "youthful beloved in a male homosexual liaison".[21] Therefore, it has been suggested, Cleïs was one of Sappho's younger lovers, rather than her daughter.[21] Judith Hallett argues, however, that the language used in fragment 132 suggests that Sappho was referring to Cleïs as her daughter.[22]

According to the Suda, Sappho was married to Kerkylas of Andros.[4] However, the name appears to have been invented by a comic poet: the name "Kerkylas" comes from the word kerkos, meaning "penis", and is not otherwise attested as a name,[23] while "Andros", as well as being the name of a Greek island, is similar to the Greek word ανερ (aner), which means man.[12] Thus, the name can be translated as "Dick Allcock from the Isle of Man".[23]

Judging from the inscribed chronology on the Parian Marble, Sappho was exiled from Lesbos to Sicily sometime between 604 and 594 BC.[10] This may have been as a result of her family's involvement with the conflicts between political elites on Lesbos in this period.[24] If Fragment 98 of her poetry is accepted as biographical evidence and as a reference to her daughter, it may indicate that she had already had a daughter by the time she was exiled. If Fragment 58 is accepted as autobiographical, it indicates that she lived into old age. If her connection to Rhodopis is accepted as historical, it indicates that she lived into the mid-6th century BC.[11][25]

A tradition going back at least to Menander (Fr. 258 K) suggested that Sappho killed herself by jumping off the Leucadian cliffs for love of Phaon, a ferryman. This is regarded as unhistorical by modern scholars, perhaps invented by the comic poets or originating from a misreading of a first-person reference in a non-biographical poem.[26] The legend may have resulted in part from a desire to assert Sappho as heterosexual.[27]

Sexuality and community

Today, Sappho is a symbol of female homosexuality; the common term lesbian is an allusion to Sappho.[lower-alpha 7][28] However, she has not always been so considered. In classical Athenian comedy, Sappho was caricatured as a promiscuous heterosexual woman,[29] and it is not until the Hellenistic period that the first testimonia which explicitly discuss Sappho's homoeroticism are preserved.[5] However, these ancient authors do not appear to have believed that Sappho did, in fact, have sexual relationships with other women, and as late as the tenth century the Suda records that Sappho was "slanderously accused" of having sexual relationships with her "female pupils".[30]

.jpg)

Among modern scholars, Sappho's sexuality is still debated. Early translators of Sappho sometimes heterosexualised her poetry,[31] with Alessandro Verri arguing that fragment 31 is about Sappho's love for Phaon.[32] Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker argued that Sappho's feelings for other women were "entirely idealistic and non-sensual"[33] while Karl Otfried Müller wrote that fragment 31 described "nothing but a friendly affection":[34] Glenn Most comments that "one wonders what language Sappho would have used to describe her feelings if they had been ones of sexual excitement" if this theory were correct.[34] By 1970, it would be argued that the same poem contained "proof positive of [Sappho's] lesbianism".[35]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff posited that Sappho was a sort of schoolteacher, in order to "explain away Sappho's passion for her 'girls'" and defend her from accusations of homosexuality.[36] More recently, however, historians have noted that the idea of schools in archaic Greece is anachronistic.[37] Additionally, none of Sappho's own poetry mentions her teaching, and the earliest testimonium to support the idea of Sappho as a teacher comes from Ovid, six centuries after Sappho's lifetime.[38]

One of the major focuses of scholars studying Sappho has been to attempt to determine the cultural context in which Sappho's poems were composed and performed.[39] Various cultural contexts and social roles played by Sappho have been suggested, including teacher, cult-leader, and poet performing for a circle of female friends.[39] However, the performance contexts of many of Sappho's fragments are not easy to determine, and for many more than one possible context is conceivable.[40]

One longstanding and still influential suggestion of a social role for Sappho is that of "Sappho as schoolmistress".[41] This view was first put forward by Wilamowitz at the beginning of the twentieth century,[36] and is still influential, both amongst scholars and the general public.[42] Though the idea of Sappho as a schoolteacher is now recognised as anachronistic,[37] many newer interpretations of Sappho's social role are still based on this idea.[43] In these interpretations, Sappho was involved in the ritual education of girls,[43] for instance as a trainer of choruses of girls.[39]

Even if Sappho did compose songs for training choruses of young girls, however, not all of her poems can be interpreted in this light,[44] and despite scholars' best attempts to find one, Yatromanolakis argues that there is no single performance context which all of Sappho's poems can be attributed to. Parker argues that Sappho should be considered as part of a group of female friends for whom she would have performed, just as her contemporary Alcaeus is.[45] Some of her poetry appears to have been composed for identifiable formal occasions,[46] but many of her songs are about – and possibly were to be performed at – banquets.[47]

Works

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, 650 survive.[48] She is best known for her lyric poetry, designed to be accompanied by music.[48] The Suda also attributes to Sappho epigrams, elegiacs, and iambics, but the only epigrams attributed to Sappho to survive are in fact later works, and this is probably also the case with her supposed iambic and elegiac output.[49] Ancient authors claim that Sappho primarily wrote love poetry,[50] and the indirect transmission of Sappho's work supports this notion.[51] However, the papyrus tradition suggests that this may not have been the case: a series of papyri published in 2014 contain fragments of ten consecutive poems from Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho, of which only two are certainly love poems, while at least three and possibly four are primarily concerned with family.[51]

Ancient editions

Around the second century BCE, Alexandrian scholars produced at least two critical editions of Sappho's poetry; one edited by Aristophanes of Byzantium and another by Aristarchus of Samothrace, a pupil of Aristophanes.[52] The Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry was divided into at least eight books, though the exact number is uncertain.[53] In this edition, Sappho's poems were probably grouped by metre, and ancient sources tell us that each of the first three books contained poems in a single specific metre.[54] Ancient editions of Sappho, possibly starting with the Alexandrian edition, seem to have ordered the poems in at least the first book of Sappho's poetry – the volume containing the poetry written in Sapphic stanzas – alphabetically.[55]

In addition to the Alexandrian edition, at least some of Sappho's poetry was in circulation in the ancient world in other collections. Some of the preserved manuscripts of Sappho's poetry, such as the ostrakon on which fragment 2 is preserved, are from the third century BC, predating the standard edition of Sappho's poetry.[52] The Cologne Papyrus on which the Tithonus poem is preserved was part of a Hellenistic anthology of poetry.[56]

Loss and preservation

Although Sappho's work endured well into Roman times, her work was copied less and less as interests, styles, and aesthetics changed, especially after the academies stopped requiring her study. Part of the reason for her disappearance from the standard canon was the predominance of Attic and Homeric Greek as the languages required to be studied. Sappho's Aeolic Greek dialect is a difficult one, and by Roman times it was arcane and ancient as well, posing considerable obstacles to her continued popularity. Still, the greatest poets and thinkers of ancient Rome continued to emulate her or compare other writers to her, and it is through these comparisons and descriptions that we have received much of her extant poetry.

Once the major academies of the Byzantine Empire dropped her works from their standard curricula, very few copies of her works were made by scribes, and the 12th-century Byzantine scholar Tzetzes speaks of her works as lost.[57]

Modern legends describe Sappho's literary legacy as being the victim of purposeful obliteration by scandalized church leaders, often by means of book-burning.[58] However, modern scholars have noted the echoes of Sappho Fragment 2 in a poem by Gregory of Nazianzus, a Father of the Church. Gregory's poem On Human Nature copies from Sappho the quasi-sacred grove (alsos), the wind-shaken branches, and the striking word for "deep sleep" (kōma).[59][60] On the other hand, historian Will Durant, citing Mahaffy, reports that "In the year 1073 of our era the poetry of Sappho and Alcaeus was publicly burned by ecclesiastical authorities in Constantinople and Rome."[61]

Surviving poetry

Today, most of Sappho's poetry is lost. Of approximately 650 lines which survive, only one poem – the "Ode to Aphrodite" – is complete, and more than half of the original lines survive in around ten more fragments. Many of the surviving fragments of Sappho contain only a single word[48] – for example, fragment 169A is simply a word meaning "wedding gifts",[62] and survives as part of a dictionary of rare words.[63]

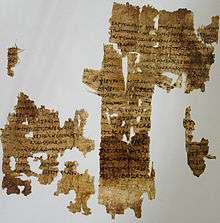

The two major sources of surviving fragments of Sappho are quotations in other ancient works, from a whole poem to as little as a single word, and fragments of papyrus, many of which were discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt.[64] Other fragments survive on other materials, including parchment and potsherds.[49] The oldest surviving fragment of Sappho currently known is the Cologne papyrus which contains the Tithonus poem,[65] dating to the third century BC.[66]

Until the end of the nineteenth century, when Grenfell and Hunt began to excavate an ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus, only the ancient quotations of Sappho survived. The papyri found there included many previously unknown fragments of Sappho.[12] Fragments of Sappho continue to be rediscovered. Most recently, major discoveries in 2004 (the "Tithonus poem" and a new, previously unknown fragment)[67] and 2014 (fragments of nine poems; five already known but with new readings, four, including the "Brothers Poem", not previously known)[68] have been reported in the media around the world.[12]

Style

Sappho's poetry is known for its clear language and simple thoughts, sharply-drawn images, and use of direct quotation which brings a sense of immediacy.[69] Unexpected word-play is a characteristic feature of her style.[70] An example is from fragment 96: "now she stands out among Lydian women as after sunset the rose-fingered moon exceeds all stars",[71] a variation of the Homeric epithet "rosy-fingered Dawn".[72] Sappho's poetry often uses hyperbole, according to ancient critics "because of its charm";[73] an example is found in fragment 111, where Sappho writes that "The groom approaches like Ares[...] Much bigger than a big man".[74]

Legacy

_-_BEIC_6353771.jpg)

Ancient reputation

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired. Several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse",[75] including an epigram attributed to Plato.[76] She was sometimes referred to as "The Poetess", just as Homer was "The Poet".[77] The scholars of Alexandria included Sappho in the canon of nine lyric poets.[78] According to Aelian, the Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon asked to be taught a song by Sappho "so that I may learn it and then die". This story may well be apocryphal, especially as Ammianus Marcellinus tells a similar story about Socrates and a song of Stesichorus, but it does tell us something about ancient opinions of the quality of Sappho's poetry.[79]

Sappho's poetry also influenced other ancient poets. For instance, Catullus 51 (Ille mi par esse deo videtur) is an adaptation and translation of Sappho's 31st fragment.[80][81] Still more ancient poets wrote about Sappho's life. Ovid's Heroides 15 is written as a letter from Sappho to her supposed love Phaon, and when it was first re-discovered in the 15th century was thought to be a translation of an authentic letter of Sappho's.[82] Sappho was a popular character in ancient Athenian comedy,[29] and Parker lists six separate comedies called Sappho.[83][lower-alpha 8]

Modern reception

Like the ancients, modern critics have tended to consider Sappho "extraordinary".[84] Her poetry has influenced such modern poets as A. E. Housman, who adapted the Midnight poem – long thought to be by Sappho, though the authorship is now disputed – for three separate works, as well as Sappho's fragment 93.[85] Tennyson was also influenced by the Midnight poem,[86] as well as fragment 31 – on which two poems, "Eleanore" and "Fatima" are based.[87]

The discoveries of new poems by Sappho in 2004 and 2014 excited both scholarly and media attention.[12] The announcement of the Tithonus poem was the subject of international news coverage, and was described by Marylin Skinner as "the trouvaille of a lifetime".[67] The publication in 2014 of the Brothers poem was described as "more exciting than a new album by David Bowie" by the Daily Telegraph.[88]

However, today Sappho is perhaps better known for her sexuality than her poetry. While in the 18th century, Sappho was a symbol of unrequited female heterosexual desire,[89] by the 20th century she had become a symbol of homosexuality, especially female homosexuality: indeed, the English words "sapphic" and "lesbian" both refer to Sappho.[28]

Translations into English

The metrical forms used in Sappho's poetry are difficult to reproduce in English, as Ancient Greek meters were based on syllable length, while English meters are based on stress patterns and rhyming schemes.[90] Early translators often dealt with this problem by translating Sappho's works into English metrical forms. Still, the Sapphic stanza, strongly associated with Sappho's poetry in the original, has become well known and influential among modern poets as well.[91]

Modern interest in Sappho's writing began with the European Renaissance, starting in France and later spreading to England. Sappho was first translated into English by John Hall, in his 1652 translation of Longinus' On the Sublime, which contains fragment 31.[92] Translations of Sappho's work as such began to appear in the 18th century, starting with Ambrose Philips' translations of fragments 1 and 31 published in The Spectator in 1711.[93] In 1877, Henry T. Wharton published an authoritative reading edition of Sappho's fragments in translation, which dominated the reading of Sappho for several decades.[94] Wharton's edition included both his own prose renderings and previous verse translations by others.[95]

In 1904, Canadian poet Bliss Carman published Sappho: One Hundred Lyrics, which was not just a translation of the fragments but an imaginative reconstruction of the lost poems. While of little to no scholarly value, Carman's translations brought Sappho's work to the attention of a wide readership. In the 1920s, several major translations appeared: the Loeb Classical Library translation by John Maxwell Edmonds in 1922, prose and selected verse translations by Edwin Marion Cox in 1924, and combined prose and verse translations by David Moore Robinson and Marion Mills Miller in 1925.[96]

In the 1960s, Mary Barnard introduced new approach to the translation of Sappho that eschewed the use of rhyming stanzas and traditional forms. Subsequent translators have tended to work in a similar manner. In 2002, classicist and poet Anne Carson produced If Not, Winter, an exhaustive translation of Sappho's fragments. Her line-by-line translations, complete with brackets where the ancient papyrus sources break off, are meant to capture both the original's lyricism and its present fragmentary nature. Translations of Sappho have also been produced by Willis Barnstone, Richmond Lattimore, Paul Roche, Jim Powell, Guy Davenport, and Stanley Lombardo.[97] The first translation of Sappho into English to contain the fragments discovered in 2014, including the "Brothers Poem", was Diane Rayor's Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works.[12]

See also

- Ancient Greek literature

- Midnight poem – one of the best known poems attributed to Sappho, its authorship is now disputed

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 7 – papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 5

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231 – papyrus preserving Sappho frr. 15–30

Notes

- ↑ The fragments of Sappho's poetry are conventionally referred to by fragment number, though some also have one or more common names. The most commonly used numbering system is that of E. M. Voigt, which in most cases matches the older Lobel-Page system. Unless otherwise specified, the numeration in this article is from Diane Rayor and André Lardinois' Sappho: A New Edition of the Complete Works, which uses Voigt's numeration with some variations to account for the fragments of Sappho discovered since Voigt's edition was published.

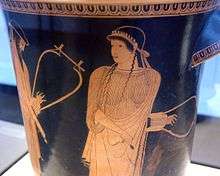

- ↑ The oldest of the testimonia are four Attic vase-paintings of Sappho, dating to the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC.[4]

- ↑ According to the Suda she was from Eresos rather than Mytilene;[4] most testimonia and some of Sappho's own poetry point to Mytilene, however.[9]

- ↑ Strabo says that she was a contemporary of Alcaeus and Pittacus; Athenaeus that she was a contemporary of Alyattes, king of Lydia. The Suda says that she was active during the 42nd Olympiad, while Eusebius says that she was famous by the 45th Olympiad.[11]

- ↑ The Suda lists Simon, Eumenus, Eerigyius, Ecrytus, Semus, Camon, Etarchus, and Scamandronymus as possible names for Sappho's father.[13] The Oxyrhynchus biography says that he was called Scamander or Scamandronymus.[14]

- ↑ Other sources say that Charaxus' lover was called Doricha, rather than Rhodopis.[19]

- ↑ The adjective "sapphic", and the related "sapphist", "sapphism" etc. all also come from Sappho.

- ↑ Parker lists plays by Ameipsias, Amphis, Antiphanes, Diphilos, Ephippus, and Timocles, along with two plays called Phaon, four called Leucadia, one Leukadios, and one Antilais all of which may have been about Sappho.

References

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 1.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 4.

- 1 2 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Winkler 1990, p. 168.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 321.

- ↑ Hutchinson 2001, p. 139.

- ↑ Hutchinson 2001, p. 140, n.1.

- 1 2 Campbell 1982, p. xi.

- 1 2 Campbell 1982, pp. x–xi.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mendelsohn 2015.

- 1 2 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 3.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 15, n.1.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. xi, 189.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. 15, 187.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories, 2.135

- 1 2 Hallett 1982, p. 22.

- ↑ Hallett 1982, pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 Parker 1993, p. 309.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Page 1955, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Lidov 2002, pp. 205–6, n.7.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, pp. 448–449.

- 1 2 Most 1995, p. 15.

- 1 2 Most 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, p. 448.

- ↑ Gubar 1984, p. 44.

- ↑ Most 1995, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 26.

- 1 2 Most 1995, p. 27.

- ↑ Devereux 1970.

- 1 2 Parker 1993, p. 313.

- 1 2 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 314–316.

- 1 2 3 Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 216.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, pp. 216–218.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 310.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 314–315.

- 1 2 Parker 1993, p. 316.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 218.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 342.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 343.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 344.

- 1 2 3 4 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. xii.

- 1 2 Bierl & Lardinois 2016, p. 3.

- 1 2 Winkler 1990, p. 166.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 181.

- ↑ Lidov 2011.

- ↑ Obbink 2016, p. 42.

- ↑ Clayman 2011.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 81.

- ↑ Cataudella 1940, pp. 199–201.

- ↑ Page 1955, p. 37.

- ↑ Durant 1939, p. 155.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 148.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ West 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Obbink 2011.

- 1 2 Skinner 2011.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 155.

- ↑ Campbell 1967, p. 262.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 435.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 66.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 439.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 438.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 73.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, p. 447.

- ↑ Greek Anthology, 9.506

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 312.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 340.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 221.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 30.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 19.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 309–310, n. 2.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, p. 449.

- ↑ Sanford 1942, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Peterson 1994, p. 121.

- ↑ Peterson 1994, p. 123.

- ↑ Payne 2014.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 18.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 24.

- ↑ Schulman 2002, p. 132.

- ↑ Wilson 2012, p. 501.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 123.

- ↑ McPharlin 1942, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ McPharlin 1942, p. 4.

- ↑ McPharlin 1942, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Pavlovskis-Petit 2000, pp. 1227-1228.

Works cited

- Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André (2016). "Introduction". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André. The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Campbell, D. A. (1967). Greek lyric poetry: a selection of early Greek lyric, elegiac and iambic poetry.

- Campbell, D. A. (ed.) (1982). Greek Lyric 1: Sappho and Alcaeus (Loeb Classical Library No. 142). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. ISBN 0-674-99157-5.

- Cataudella, Quintino (1940). "Saffo fr. 5 (5) – 6 (5) Diehl". Atene e Roma. 8 (3).

- Clayman, Dee (2011). "The New Sappho in a Hellenistic Poetry Book". Classics@. 4.

- Devereux, George (1970). The Nature of Sappho's Seizure in Fr. 31 LP as Evidence of Her Inversion. The Classical Quarterly. 20.

- Durant, Will (1939). The Life of Greece. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Fairweather, J. (1974). "Fiction in the biographies of ancient writers". Ancient Society. 5. ISSN 0066-1619.

- Gubar, Susan (1984). "Sapphistries". Signs. 10 (1).

- Hallett, Judith P. (1979). "Sappho and her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality". Signs. 4 (3).

- Hallett, Judith P. (1982). "Beloved Cleïs". Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica. 10.

- Hutchinson, G. O. (2001). Greek Lyric Poetry: A Commentary on Selected Larger Pieces. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924017-5.

- Lefkowitz, Mary R. (1981). The Lives of the Greek Poets. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2748-5.

- Lidov, Joel (2002). "Sappho, Herodotus and the Hetaira". Classical Philology. 97 (3).

- Lidov, Joel (2011). "The Meter and Metrical Style of the New Poem". Classics@. 4.

- McPharlin, Paul (1942). The Songs of Sappho in English Translation by Many Poets.

- Mendelsohn, Daniel (16 March 2015). "Girl, Interrupted: Who Was Sappho?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Most, Glenn W. (1995). "Reflecting Sappho". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 40.

- Obbink, Dirk (2011). "Sappho Fragments 58–59: Text, Apparatus Criticus, and Translation". Classics@. 4.

- Obbink, Dirk (2016). "Ten Poems of Sappho: Provenance, Authority, and Text of the New Sappho Papyri". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André. The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Parker, Holt (1993). "Sappho Schoolmistress". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 123.

- Page, D. L. (1955). Sappho and Alcaeus. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Pavlovskis-Petit, Zoja (2000). "Sappho". In O. Classe. Encyclopedia of Literary Translation Into English: A-L. pp. 1227–1229. ISBN 9781884964367.

- Payne, Tom (30 January 2014). "A new Sappho poem is more exciting than a new David Bowie album". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Peterson, Linda H. (1994). "Sappho and the Making of Tennysonian Lyric". ELH. 61 (1).

- Rayor, Diane; Lardinois, André (2014). Sappho: A New Edition of the Complete Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02359-8.

- Reynolds, Margaret (2002). The Sappho Companion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312239244.

- Sanford, Eva Matthews (1942). "Classical Poets in the Work of A. E. Housman". The Classical Journal. 37 (4).

- Schulman, Grace (2002). "Sapphics". In Finch, Annie; Varnes, Kathrine. An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art. ISBN 9780472067251.

- Skinner, Marilyn B. (2011). "Introduction". Classics@. 4.

- West, Martin. L. (2005). "The New Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 151.

- Wilson, Penelope (2012). "Women Writers and the Classics". In Hopkins, David; Martindale, Charles. The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature: Volume 3 (1660-1790). ISBN 9780199219810.

- Winkler, John J. (1990). The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415901235.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (1999). "Alexandrian Sappho Revisited". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 99.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2009). "Alcaeus and Sappho". In Budelmann, Felix. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139002479.

- Zellner, Harold (2008). "Sappho's Sparrows". The Classical World. 101 (4).

Further reading

- Barnard, Mary (1958). Sappho: A New Translation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Boehringer, Sandra (2007). L'homosexualité féminine dans l'Antiquité grecque et romaine. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782251326634.

- Burris, Simon; Fish, Jeffrey; Obbink, Dirk (2014). "New Fragments of Book 1 of Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 189.

- Carson, Anne (2002). If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41067-8.

- Duban, Jeffrey M. (1983). Ancient and Modern Images of Sappho: Translations and Studies in Archaic Greek love Lyric. University Press of America.

- DuBois, Page (1995). Sappho Is Burning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-16755-0.

- Lobel, E.; Page, D. L., eds. (1955). Poetarum Lesbiorum fragmenta. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Obbink, Dirk (2014). "Two New Poems By Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 189.

- Voigt, Eva-Maria (1971). Sappho et Alcaeus. Fragmenta. Amsterdam: Polak & van Gennep.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2007). Sappho in the Making: the Early Reception. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674026865.

External links

- Texts and translations

- Sappho Translations (Sappho translations by major poets like Ben Jonson, Lord Byron and T. S. Eliot)

- The Divine Sappho (Greek texts and several translations, with essays and criticism)

- aoidoi.org (Greek texts with commentary by William Annis)

- The Poems of Sappho, trans. E.M. Cox (1925 translation with Greek text and transliteration)

- The sound of Sappho? (MP3 audio of five fragments in Greek)

- Read Two Newly Discovered Sappho Poems in English for the First Time (translation of previously unpublished poems whose discovery was announced in 2014)

- Greek and Roman love poetry, BBC Radio 4, In Our Time, 26 April 2007

- Sappho, BBC Radio 4, In Our Time

- BBC Radio 4 - Great Lives, Series 22, Sappho

- BBC Radio 4 - Woman's Hour -Sappho

- SORGLL: Sappho 1; read by Stephen Daitz

- Sappho : the "Brothers Poem" (discov. 2014) (text, transl., audio, recited in Greek by Ioannis Stratakis)

- Sappho and the World of Lesbian Poetry, by William Harris, Prof. Em. of Classics, Middlebury College

- Reading Sappho, by Ellen Greene, UC Press

- Sappho's New Poems: The Tangled Tale of Their Discovery (January 2015), LiveScience

- Works by Sappho at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sappho at Internet Archive

- Works by Sappho at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)